Abstract

Stakeholder fragmentation in transdisciplinary research often impedes innovation in South Africa’s tourism sector. The real-time supply network for MSMEs in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal struggles with digital adoption, limiting its resilience despite rising demand in the digital economy. This study examined how a transdisciplinary approach can enhance the Tourism Supply Chain Network in these regions—an urban hub (Gauteng) and a coastal cultural destination (KwaZulu-Natal)—to unlock their potential. Employing action research, this study engaged stakeholders (tourism operators, tech developers, and communities) to co-create data-driven digital solutions, including a real-time supply network. The collected data included both qualitative insights from workshops and interviews, as well as quantitative metrics such as platform usage and tourist engagement, which were analysed using descriptive statistics. Innovative technologies improved the supply chain efficiency, cutting coordination delays by 25% in Gauteng and boosting rural tourism visibility in KwaZulu-Natal, with a 30% increase in bookings. Gauteng saw urban connectivity gains, while KwaZulu-Natal achieved inclusive growth. This study provides a scalable, data-driven framework for digitalisation in tourism supply networks, offering practical strategies for stakeholders. It advances innovative technologies in emerging markets, emphasising the transformative potential of transdisciplinary collaboration to build resilient, collaborative tourism ecosystems in South Africa.

1. Introduction

The number of transdisciplinary research projects involving researchers partnering for sustainability initiatives is rising globally (Boersema et al., 2024; Augenstein et al., 2024; Sharia & Sitchinava, 2023). Transformative Transdisciplinary Research (TTDR) is urgently needed to provide knowledge and guidance for actions (Augenstein et al., 2024). Such transformation has far-reaching effects, not only in recrafting balance in the business and opportunity landscapes but also for local communities and previously disadvantaged groups. In the Tourism Supply Chain Network (TSCN), fragmented coordination hinders the effectiveness and efficiency of delivering travel experiences. Inefficient use of resources within the supply chain causes delays, higher expenses, and a worsened visitor experience (García-Gómez et al., 2023). Nevertheless, the tourism industry relies on a complex network of interconnected businesses and organisations (including Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises, MSMEs), forming the TSCN. According to Huang et al. (2013), the TSCN comprises three sectors: theme parks, accommodation providers, and tour operators. Recent developments in information systems and technologies have enhanced the performance of the tourism supply chain by making real-time information available for the coordination of various actors in the supply chain. This is referred to as e-Supply Chain Management (eSCM) (Zhang & Tavitiyaman, 2022).

Despite the increasing role of digital technologies in tourism supply networks, many MSMEs, local tourism operators, and emerging destinations struggle with digital adoption, integration, and scalability. The lack of a holistic, multi-stakeholder approach that bridges academic insights with real-world implementation hinders the effective transformation of the tourism supply network. This study addresses the gap between digitalisation theory and practical implementation, ensuring that digital transformation efforts are both technologically advanced and socially and economically inclusive.

There is a lack of effective strategies to overcome compartmentalisation within the TSCN when implementing TTRD. While TTRD promotes a holistic view and cooperation among stakeholders, challenges such as sector-based optimisation and neglect of interconnectedness hinder the full realisation of system-wide sustainability and competitiveness. This study aims to apply a TTDR approach to evaluate the effect of digitalisation in the TSCN and co-design and co-produce digitalised MSMEs’ transformative knowledge from a praxis (Afrocentric) approach in South Africa. This study intends to fill the digital skills gap in the digital labour market in South Africa (Department of Communication and Digital Technologies [DCDT], 2024), which hinders progress for the MSMEs in the tourism value chain to benefit from digitalisation.

2. Literature Review

The rapid evolution of digitalisation in tourism necessitates a shift from traditional sectoral analyses toward integrated, data-driven approaches that enhance resilience and collaboration within the Tourism Supply Chain Network (TSCN). This review was conducted based on the study of innovative technologies and data science, exploring their application in tourism and the transformative potential of transdisciplinary frameworks, while identifying gaps that are relevant to Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal.

2.1. Smart Technologies in Tourism

Innovative technologies are revolutionising tourism supply networks by enabling real-time coordination and efficiency. Mobile applications streamline booking processes and enhance customer engagement (Gretzel et al., 2015), while blockchain ensures secure, transparent transactions across supply chain actors, such as hotels and tour operators (Önder & Treiblmaier, 2018). Real-time analytics, powered by Internet of Things (IoT) devices, provide actionable insights into tourist flows and resource allocation (Buhalis & Law, 2008). For instance, innovative European destination systems use IoT to monitor visitor patterns and optimise supply network performance (Gretzel et al., 2015). However, their adoption in emerging markets such as South Africa remains limited, often due to infrastructure and cost barriers (Dlamini, 2024), underscoring the need for context-specific implementations.

2.2. Data Science Applications

Data science enhances decision-making in tourism by transforming raw data into strategic insights. Predictive modelling forecasts demand trends, aiding inventory management in the TSCN (Li & Liu, 2018), while sentiment analysis of social media feedback refines marketing strategies and customer experiences (Xiang et al., 2017). Real-time data analytics, such as those derived from mobile app usage, enable dynamic pricing and resource optimisation (Buhalis & Law, 2008). Studies have demonstrated that data-driven approaches improve operational efficiency—for example allowing for a 20% reduction in overbooking errors in European hotel chains (Li & Liu, 2018)—yet their application in South African tourism remains underexplored, particularly in integrating supply network stakeholders (Sifolo, 2023b).

2.3. Transdisciplinary Frameworks

Transdisciplinary research (TDR) integrates technological expertise with tourism practices, fostering innovative solutions to complex challenges. Rooted in the concept of “science with society” Khokhobaia (2018), TDR combines disciplinary knowledge—e.g., data science, economics, and sociology—with experiential insights from practitioners and communities (van Breda, 2019). In this article, MSMEs, tourism operators, tech developers, and communities participated. TDR facilitates collaboration across the TSCN in tourism, bridging gaps between tech developers and tourism operators (Hall, 2014). For example, Tschanz et al. (2022) applied TDR to integrate ecological and economic data for climate-resilient destination management. Digitalisation amplifies this approach by providing tools like dashboards synthesising diverse data streams. Nevertheless, its transformative potential requires a theory of change that is tailored to specific contexts, as shown by van Breda (2019), a gap that this study addresses in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal.

2.4. Resilience and Collaboration

Resilience and collaboration are critical to a sustainable TSCN, particularly during disruptions like pandemics. Data-driven recovery strategies, such as predictive analytics for demand rebound, enhance resilience by enabling proactive adjustments (Gu et al., 2024). Collaboration, however, leverages innovative technologies to connect stakeholders; for example, real-time platforms can be used to link hotels, transport providers, and local communities (Gretzel et al., 2015). Stevenson (2012) argues that tourism’s complexity demands such synergy, a view supported by Hall (2014), who emphasises the importance of stakeholder cooperation for sustainability. In South Africa, digital tools could strengthen urban–rural linkages. However, challenges such as data privacy concerns, high implementation costs, the need for skilled personnel, integration complexities (Dlamini, 2024), digital literacy, and stakeholder silos persist (Xiang et al., 2017), limiting data-driven resilience and collaboration.

2.5. Research Gap

While innovative technologies and data science offer transformative potential for the TSCN, data-focused studies on digitalisation in South African tourism are scarce. The existing research is disciplinary, neglecting integrating social, economic, and environmental dimensions through a transdisciplinary lens (Huang et al., 2013). In Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal, where urban and rural tourism dynamics diverge, the lack of context-specific, data-driven frameworks hinders progress toward resilience and collaboration (Sifolo, 2023a). This research tackles this gap by examining the application of transformative transdisciplinary approaches, incorporating innovative technologies and data science, to optimise the TSCN in these regions.

2.6. The Theoretical Lens Adopted in This Study

This section explores theoretical frameworks that are relevant to digitalisation in the Tourism Supply Chain Network (TSCN). It examines adaptation theory and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) to understand how tourism stakeholders—particularly MSMEs—navigate digital transformation in South Africa’s TSCN. Adaptation theory, originating in the 1950s from film and literature studies, emphasises organisational adjustment to changing environments, such as digital or social supply chain networks (Hutcheon, 2006). It posits that judgments about new stimuli, such as digital tools, are relative to individuals’ past experiences and internal norms (Suk et al., 2010). While valuable for understanding creative adaptation and storytelling in tourism marketing (e.g., adjusting to social media), it fails to explain MSMEs’ specific digital transformation needs in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal, where rapid technological shifts demand practical adoption strategies. This limitation highlights the need for a more robust framework to address resilience and collaboration in the TSCN.

To bridge this gap, this study adopts the UTAUT, developed by Venkatesh et al. (2003), which provides a comprehensive model for technology acceptance. The UTAUT identifies four core determinants—performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions—that are moderated by gender, age, voluntariness, and experience. These factors are critical for evaluating how MSMEs in Gauteng (urban hub) and KwaZulu-Natal (coastal/rural tourism region) adopt digital tools to enhance TSCN resilience (e.g., improved performance) and collaboration (e.g., industry support). The UTAUT’s focus on intention, usage, and routine-based solutions aligns with this study’s transdisciplinary aim to integrate stakeholder perspectives and drive transformative digitalisation. By applying the UTAUT, this study assesses how MSMEs adjust workflows, acquire skills, and leverage digital platforms, addressing the contextual complexities of South Africa’s TSCN and supporting sustainable tourism development.

The UTAUT supports transformative change by identifying factors that enable MSMEs to adopt digital tools, fostering resilience and growth in the TSCN. The integration of adaptation theory (contextual adjustment) and the UTAUT (technology acceptance) reflects a crossdisciplinary approach that engages diverse stakeholders in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal. Both theories address digital tool adoption, with the UTAUT offering a practical lens for MSMEs’ technology uptake in the TSCN. However, the UTAUT’s emphasis on performance and social influence aligns with enhancing supply chain resilience and stakeholder collaboration in these regions.

2.7. Problem Statement

The digitalisation of the TSCN holds substantial potential for advancing sustainable development. However, existing research on the TSCN is often restricted to disciplinary silos such as economics, operations, marketing, and tourism management, limiting the capacity for comprehensive and transformative change. A TTDR approach, as highlighted by Khokhobaia (2018), aims to generate new knowledge by integrating existing practices, technologies, and regulations while fundamentally reshaping systems to achieve sustainability goals. Despite the acknowledged importance of transformative learning in tackling sustainability challenges such as environmental impacts and resource depletion, there is a noticeable gap in coordinated, transdisciplinary research that effectively integrates social, economic, and ecological dimensions. This research addresses this gap by developing a framework that transcends traditional disciplines, enabling a cohesive digitalisation strategy within the tourism supply network that supports sustainable development.

Grounded in the study context, incorporating insights from the literature review, and aligning with the focus on digitalisation, resilience, and collaboration, the research question for this study is as follows: how can transformative transdisciplinary approaches, leveraging innovative technologies and data-driven collaboration, enhance resilience and stakeholder connectivity within the Tourism Supply Chain Network (TSCN) in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal?

3. Materials and Methods

This study explores the adoption of digital technologies in the Tourism Supply Chain Network (TSCN) in South Africa through a Transformational Transformative Research (TTDR) approach. It adopts an embedded experimental model to evaluate the digitalisation experiences of MSMEs in KwaZulu Natal and Gauteng provinces, fostering collaboration between academic researchers and non-academic social actors.

3.1. Research Design: Co-Designing and Co-Producing Digitalised MSMEs’ Transformative Knowledge from a Praxis (Afrocentric) Approach

Co-design and co-creation as concepts in tourism need to be developed through further research to become a real trend and enable meaningful participation in the tourism industry for MSMEs. The research design adopted is the TTDR Narrative Action Research process by van Breda (2019), which integrates preparation, design, narrative data collection, analysis, sense-making, returning stories, and implementing and performing Vector Monitoring and Evaluation (VME). Action research principles guide the process, reconnecting knowledge with practice to drive real-world impact.

3.2. Research Process

The preparation phase lays the foundation for investigating digitalisation within the Tourism Supply Chain Network (TSCN) through a Transformative Transdisciplinary Research (TTDR) lens. This study tackles two critical challenges in South Africa’s tourism sector: a pronounced digital skills gap in the labour market, as identified by the Department of Communication and Digital Technologies [DCDT] (2024), and the sluggish pace of digital transformation among Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs), as noted in the National Department of Tourism’s strategy (2018). These issues hinder the TSCN’s ability to adapt to technological advancements and compete globally, particularly in regions like Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal, where urban and rural tourism dynamics diverge. This study is guided by two key questions: (1) How can the TTDR approach evaluate the impact of digitalisation in the TSCN? (2) How can digitalised MSMEs’ transformative knowledge be co-designed and co-produced using an Afrocentric praxis approach? The first question seeks to assess the effectiveness of TTDR in measuring digitalisation’s contributions to resilience and collaboration. In contrast, the second question emphasises co-creation with an Afrocentric focus, prioritising local knowledge and cultural context to ensure relevance and inclusivity in the digital transformation.

3.3. Population and Sampling

This study engages a diverse set of participants to reflect the transdisciplinary nature of the research. The population includes MSMEs (e.g., tour operators and accommodation providers), tourism professionals (e.g., consultants and marketers), technology specialists (e.g., app developers and data analysts), policymakers (e.g., government officials), and community representatives (e.g., local tourism offices). This mix ensures a broad perspective on digitalisation’s impact across the TSCN. A multi-track sampling strategy combines legitimised social actors (e.g., government and academic stakeholders) with non-legitimised actors (e.g., informal MSMEs and community leaders), fostering co-creation and inclusivity in tourism innovation, as advocated by van Breda (2019). In KwaZulu-Natal, 122 MSMEs participated in workshops, reflecting the region’s diverse tourism base, including coastal and rural enterprises. In Gauteng, 87 participants attended a seminar representing urban tourism stakeholders with access to advanced digital infrastructure. These sample sizes were determined pragmatically to balance the depth of engagement with resource constraints, ensuring representation across the TSCN.

3.4. Data Collection Tools

Multiple tools were employed to capture rich, multi-faceted data on digitalisation experiences. Semi-structured interviews, conducted online (via WhatsApp and phone calls) and in person, allowed for an in-depth exploration of MSMEs’ digital adoption challenges and opportunities. The Annual Tourism Week event in KwaZulu-Natal served as an interactive platform for stakeholder dialogue and practical demonstrations of digital tools. Online surveys, administered through Microsoft Forms, WhatsApp, and Facebook engagement posts, collected quantitative and qualitative feedback pre- and post-intervention, leveraging social media’s reach (e.g., 753,000 impressions in KwaZulu-Natal). An online survey included the background of the study, and the participants consented in an online survey and on the day of the event through the attendance register. Multi-stakeholder discussions facilitated collaborative sense-making among participants, uncovering collective insights on digital needs. Participant observations during MSMEs’ digital adoption processes provided contextual data on real-time barriers and successes, enhancing the study’s practical relevance. The research unfolded in three iterative phases, aligning with TTDR’s action-oriented principles. Phase 1 included Track 1, in which research engagement was facilitated. The initial exploration involved 12 MSMEs assessing the baseline digitalisation levels in the TSCN and identifying gaps like limited access to innovative technologies. Phase 2 consisted of Track 2, in which the co-creation process was followed. Collaboration with a tourism consulting firm in KwaZulu-Natal culminated in a workshop during Annual Tourism Week, scaling up insights from Phase 1 into actionable interventions. The last phase expanded to Track 3, where a digitalisation seminar in Gauteng extended the co-creation process, tailoring solutions to an urban context. The workshop hosted in KwaZulu-Natal in September 2023 attracted 120 participants, including government officials (e.g., KwaZulu-Natal Department of Economic Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs), MSMEs, academia, media, and local tourism offices from areas like Clermont and Umlazi. Topics included digital transformation, social networking in tourism, and MSME digital upskilling, with practical solutions like domain setup, email and web hosting, and website development being provided to nine MSMEs. A seminar in October 2023 engaged 91 participants—54 of whom attended in person and 37 online via MS Teams—and focused on leveraging digital economy opportunities. Panel discussions covered collaboration, networking, and digital training, highlighting urban MSMEs’ needs for Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs).

3.5. Ethical Considerations

Ethical integrity was prioritised throughout this study. Ethical clearance was secured from a reputable South African Higher Learning Institution under reference FCRE2022/FR/07/021-MS(3), ensuring compliance with research standards. Informed consent was obtained from all participants through written forms and verbal agreements clearly explaining the study’s purpose and rights. The co-creation processes adhered to ethical community engagement practices, respecting cultural sensitivities and ensuring equitable participation, particularly for non-legitimised actors like rural MSMEs, as van Breda (2019) recommended.

4. Results and Interpretation

This study’s data analysis and interpretation phase employed a multi-method approach to assess digitalisation’s impact within the Tourism Supply Chain Network (TSCN) in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal, blending qualitative and quantitative techniques for comprehensive sense-making. The qualitative analysis included a thematic analysis of interviews and workshop discussions, identifying key themes like digital adoption barriers. In contrast, the narrative analysis captured participant experiences, such as storytelling during KwaZulu-Natal’s workshop, which visualised emerging patterns with field researchers (van Breda, 2019). Social network interactions were revealed through enhanced collaboration via digital platforms (Facebook).

The quantitative analysis used descriptive statistics from surveys and social media metrics (e.g., Facebook’s 753,000 reach, 795 clicks, and 5217 engagements) to quantify engagement levels. These were real-time data-driven engagements with stakeholders such as tourism operators, tech developers, and communities in general.

The key findings from the qualitative research highlight increased awareness of digital transformation benefits; training needs in data analytics, video editing, and knowledge management (Department of Communication and Digital Technologies [DCDT], 2024); and initiated policy dialogues, including conversations on digital policy direction with government and private stakeholders in Gauteng. The practical outcomes in KwaZulu-Natal supported nine MSMEs with domain setup, emails, web hosting, and website creation, while Gauteng’s seminar, featuring six expert panellists, emphasised collaboration, social media leverage, and Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) for digital infrastructure, with discussions on innovative city initiatives like park Wi-Fi. The “Returning Stories” phase engaged successful entrepreneurs—for example, a web designer discussing ethical ChatGPT use, an entrepreneur discussing online presence via Facebook, and cybersecurity and intellectual property experts—yielding transformative insights for MSMEs. The implementation saw 40 businesses being trained in social media content, although only 7 completed certifications, with 14 receiving website boosts (7 with SEO and code updates). The Vector Monitoring and Evaluation (VME) underscored strategic digitalisation needs, identifying adaptability and agility as competitive advantages. However, challenges like low voluntariness and tracking MSMEs post-intervention (e.g., via WhatsApp and LinkedIn) revealed cooperation gaps. The co-creation adhered to ethical community engagement, respecting cultural sensitivities and ensuring equitable participation for rural MSMEs (van Breda, 2019), reinforcing best practices and overcoming barriers like infrastructure limitations (National Department of Tourism [NDT], 2018).

5. Discussion

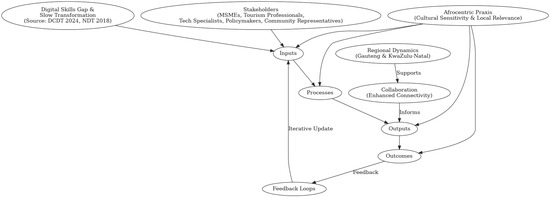

This discussion interprets the study’s findings in light of its objectives: to enhance resilience and collaboration through digitalisation in the Tourism Supply Chain Network (TSCN) and situate them within the existing literature, offering insights for theory and practice, as depicted in Figure 1 (developed using Julius Software, 2025).

Figure 1.

Transformative transdisciplinary digitalisation framework for Tourism Supply Chain Network (TSCN) (Department of Communication and Digital Technologies [DCDT], 2024; National Department of Tourism [NDT], 2018).

5.1. Digitalisation

Digitalisation significantly enhances efficiency, accessibility, and resilience in the TSCN. Providing digital tools like domain setups and websites for nine MSMEs in KwaZulu-Natal improved their operational efficiency by streamlining booking processes and customer outreach, aligning with Buhalis and Law’s (2008) findings on real-time analytics’ role in tourism optimisation. The accessibility increased as social media platforms (e.g., 753,000 Facebook reach) connected rural MSMEs to broader markets, supporting Gretzel et al.’s (2015) view of innovative technologies bridging access gaps. Resilience was bolstered through training in data analytics and cybersecurity, enabling the MSMEs to adapt to disruptions, a finding that is resonant with Li & Liu’s (2018) emphasis on predictive modelling for demand recovery. However, barriers like infrastructure limitations (National Department of Tourism [NDT], 2018) highlight the need for sustained investment to maximise these impacts.

5.2. Role of Transdisciplinary Collaboration

Transdisciplinary collaboration proved both beneficial and challenging. Integrating diverse perspectives (e.g., those of MSMEs, policymakers, and tech experts) fostered innovation, as seen in Gauteng’s seminar, where six panellists proposed PPPs and social media strategies, echoing Hall’s (2014) call for stakeholder synergy in sustainable tourism. Adhering to ethical engagement principles (van Breda, 2019), the co-creation process empowered non-legitimised actors such as rural MSMEs, enhancing the inclusivity. Nevertheless, challenges included low voluntariness and coordination difficulties, as tracking 40 trained businesses revealed only 7 completions, reflecting Vienni Baptista et al.’s (2020) concerns about transdisciplinary legitimacy and cooperation gaps. These tensions underscore the need for structured facilitation to balance diverse inputs effectively.

5.3. Regional Insights

The findings reflect distinct regional dynamics. In Gauteng, an urban hub, digitalisation enhanced supply network connectivity through platforms like MS Teams (37 remote participants) and discussions on innovative city initiatives (e.g., park Wi-Fi), aligning with its advanced infrastructure (Sifolo, 2023a). The collaboration focused on PPPs and urban efficiency, supporting Stevenson’s (2012) view of tourism as a complex system. Conversely, KwaZulu-Natal’s rural–cultural context benefited from practical solutions (e.g., website development for nine MSMEs) and storytelling, leveraging its cultural assets to boost visibility, as seen in the workshop’s 120 attendees from diverse districts. These differences highlight the need for tailored digital strategies, with urban areas prioritising scale and rural regions emphasising inclusion.

5.4. Theoretical Contributions

This study advances resilience and transdisciplinary theories. Through demonstrating how digital tools and collaboration enhance the TSCN’s adaptability, it builds on the resilience literature (Li & Liu, 2018), showing agility as a competitive advantage. The TTDR approach, integrating Afrocentric praxis and narrative analysis (van Breda & Pinkerton, 2020), extends transdisciplinary theory by operationalising knowledge co-production in a tourism context, addressing Khokhobaia’s (2018) call for socially relevant research. This linkage of practical outcomes (e.g., 14 website boosts) with theoretical frameworks offers a model for transformative change in complex systems.

5.5. Practical Implications

Actionable recommendations emerge for tourism stakeholders. MSMEs should prioritise training in data analytics and social media, as the identified needs (e.g., video editing) align with global best practices (Xiang et al., 2017). As Gauteng’s findings suggest, policymakers should foster PPPs to improve digital infrastructure, while regional tourism boards can replicate KwaZulu-Natal’s workshop model for upskilling. Industry leaders should leverage platforms like WhatsApp and Reels, which have been practically demonstrated to enhance customer engagement. These strategies, grounded in the study’s outcomes, promote a resilient, collaborative TSCN. This study aimed to enhance resilience and collaboration in the TSCN of Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal through transformative transdisciplinary approaches to digitalisation. Using a TTDR Narrative Action Research process (2020), it engaged 122 MSMEs in KwaZulu-Natal and 87 participants in Gauteng via workshops, seminars, and multi-method data collection (e.g., surveys and social network platform). Significant findings include improved collaboration via digital platforms (such as Facebook engagements), heightened digital transformation awareness, practical outcomes like website development for 14 MSMEs, and identifying barriers like training completion rates (7 of 40 certified).

The diagram below presents a structured framework for understanding digital transformation in tourism SMMEs, consisting of interconnected components. The Inputs section highlights the key challenges, including the digital skills gap and slow transformation, alongside the involvement of various stakeholders who influence the process. These inputs feed into the Processes section, facilitating transformation through targeted interventions. The Outputs section showcases the immediate results of these processes, such as increased digital adoption and enhanced collaboration. Subsequently, the Outcomes section represents the long-term impact, including improved business performance and industry competitiveness. Two critical supporting elements—Collaboration and Regional Dynamics—are vital in reinforcing the outputs, ensuring that digital transformation is adapted to local contexts. Additionally, feedback loops connect the outcomes back to the inputs, fostering an iterative cycle of continuous improvement. At the core of this framework, Afrocentric praxis serves as a foundational element, ensuring that all components align with the unique socio-cultural and economic realities of the African tourism landscape.

The study’s general research design and the findings’ representativeness were impacted by the small number of tourism MSMEs who agreed to take part. Lawrence et al. (2022), state that TTDR incorporates interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary design where participants include academic and non-academic societal actors. This study involved associations to work with researchers, students, and MSMEs on real-world issues in order to actively support action or intervention. The selection of only two associations—one in KwaZulu Natal with national, provincial, and local stakeholders, and one in Gauteng with 137 members—was another restriction brought about by response and selection bias. It was their responsibility to send out the participant invitations. Response bias may result from participants giving answers they feel associations want to hear or finds socially acceptable. Due to selection bias, this study might not adequately represent the struggles and experiences of tourism MSMEs that have not adopted digitalisation. Constraints include a modest sample size (209 total participants), potentially limiting the generalisability, and a short timeframe (2023 workshops), restricting long-term impact assessment. The reliance on voluntary participation also led to uneven follow-through, as seen in Gauteng’s training outcomes.

6. Implications

Stakeholder engagement, coordination, and participation across the value chain are encouraged for inclusive growth, sustainability, and a competitive advantage. Such collaboration is paramount in the tourism industry, as it is one of the commercial sectors that is easily affected by digital disruption. This study offers valuable insights for decision-makers seeking to navigate the digitalisation journey within the tourism value chain, harnessing opportunities while mitigating the associated risks. Managerial implications include understanding the exposure to risks, such as cybersecurity threats and data privacy concerns. Collaboration with industry peers and academia, adaptability, and flexibility emerged as critical success factors. Government support and favourable policies were seen as enablers of digital adoption. Government and policymakers should consider implementing policies promoting digital inclusion and incentivising SMEs to embrace digital technologies.

7. Conclusions

More studies exploring transdisciplinarity in the TSCN are critical to contributing to a more holistic and transformative tourism industry, benefiting practitioners and researchers. Longitudinal studies focusing on collaboration within the TSCN are needed to achieve competitiveness and reach potential organisational markets in the future. A transdisciplinary approach offers a powerful lens for understanding and optimising the TSCN. By breaking down disciplinary silos and fostering collaboration, this approach can equip stakeholders with the knowledge and tools to address complex challenges, promote responsible tourism practices, and ensure a more sustainable future for the industry. In a developing context such as South Africa, having access to travel and tourism-related business information and collaboration is critical for the TSCN to benefit individuals. However, networking between MSMEs is costly and determined “by proximity and pre-existing ties” (Moons, 2012, p. 149). Hence, digital transformation is a necessity to stay competitive and relevant. Networking and collaborating on cybersecurity threats, data privacy concerns, and the digital inclusion of certain groups could significantly impact the TSCN and tourism businesses. Stakeholders should conduct thorough research and plan before embarking on digital transformation initiatives. Future research could focus on developing frameworks or models that facilitate stronger integration and collaboration across TSCN actors, ensuring that decisions in one area positively impact others, thereby enhancing the overall resilience and sustainability of the tourism sector. Future studies could expand to other South African provinces, explore the longitudinal impacts of digitalisation on MSME performance, and investigate advanced tools like AI and blockchain, as suggested by seminar discussions. Policy-focused research could further refine PPP models for broader adoption.

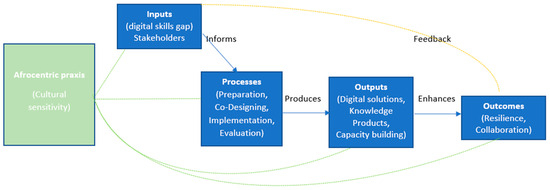

This study underscores the transformative potential of integrating innovative technologies and transdisciplinary collaboration to build a sustainable tourism ecosystem, as depicted in Figure 2. Addressing digitalisation gaps in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal offers a scalable framework for resilience and inclusivity, paving the way for a digitally empowered, collaborative TSCN.

Figure 2.

Key components of the research process.

The simplified version of Figure 2 outlines key components of the research process. It includes inputs such as the digital skills gap and stakeholders influencing the study. The Processes section consists of preparation, co-design, implementation, and evaluation, guiding the transformation journey. The Outputs section features digital solutions, knowledge products, and capacity building, contributing to tangible digitalisation advancements. The resulting outcomes emphasise resilience and collaboration among stakeholders. A feedback loop ensures continuous improvement by linking outcomes to inputs. Finally, Afrocentric praxis (cultural sensitivity) is a foundational principle, reinforcing inclusivity and relevance throughout the framework.

Funding

This research project was funded by the National Research Foundation (NRF), CSRP2204264805.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Tshwane University of Technology Research Ethics Committee, which is a registered Institutional Review Board (IRB 00005968) (or Ethics Committee) of TUT (protocol code REC Ref #: FCRE2022/FR/07/021-MS (3)) and date of approval is 14 April 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the tourism industry stakeholders in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng and the academics for their cooperation and willingness to participate.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TTRD | Transformative Transdisciplinary Research |

| TSCN | Tourism Supply Chain Network |

| MSMEs | Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises |

| UTAUT | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

| PPP | Public–Private Partnerships |

| VME | Vector Monitoring and Evaluation |

References

- Augenstein, K., Lam, D. P., Horcea-Milcu, A. I., Bernert, P., Charli-Joseph, L., Cockburn, J., Kampfmann, T., Pereira, L. M., & Sellberg, M. M. (2024). Five priorities to advance transformative transdisciplinary research. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 68, 101438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersema, G. C., van Rensburg, G. H., & Botha, B. S. (2024). Contextualising knowledge translation in nursing homes: A transdisciplinary online workshop. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 20(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D., & Law, R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tourism Management, 29(4), 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Communication and Digital Technologies [DCDT]. (2024). South Africa’s significant improvement in the United Nations e-government index. Available online: https://www.dcdt.gov.za/media-statements-releases/532-south-africa-s-significant-improvement-in-the-united-nations-e-government-index-2024.html (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Dlamini, Z. (2024). Influence of big data analytics on decision-making processes in financial firms in South Africa. American Journal of Data, Information and Knowledge Management, 5(1), 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gómez, C. D., Demir, E., Díez-Esteban, J. M., & Popesko, B. (2023). Investment inefficiency in the hospitality industry: The role of economic policy uncertainty. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 54, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U., Koo, C., Sigala, M., & Xiang, Z. (2015). Special issue on smart tourism: Convergence of information technologies, experiences, and theories. Electronic Markets, 25, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B., Liu, J., Ye, X., Gong, Y., & Chen, J. (2024). Data-driven approach for port resilience evaluation. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 186, 103570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P. (2014). Cities of tomorrow: An intellectual history of urban planning and design since 1880. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G. Q., Song, H., & Zhang, X. (2013). A comparative analysis of quantity and price competitions in tourism supply chain networks for package holidays. In Advances in service network analysis (pp. 13–26). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheon, L. (2006). A theory of adaptation. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Julius Software. (2025). Response to “Collaboration in Innovation Ecosystems”. Available online: https://julius.ai/chat?id=41c13545-2282-455a-bb49-7ddd1cc342b1 (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Khokhobaia, M. (2018). Transdisciplinary research for sustainable tourism development. Journal of International Management Studies, 18(2), 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M. G., Williams, S., Nanz, P., & Renn, O. (2022). Characteristics, potentials, and challenges of transdisciplinary research. One Earth, 5(1), 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Q., & Liu, C. H. S. (2018). The role of problem identification and intellectual capital in the management of hotels’ competitive advantage-an integrated framework. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 75, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moons, S. J. V. (2012). What are the effects of economic diplomacy on the margins of trade? International Journal of Diplomacy and Economy, 1(2), 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Department of Tourism [NDT]. (2018). Revised national tourism sector strategy. Department of Tourism. [Google Scholar]

- Önder, I., & Treiblmaier, H. (2018). Blockchain and tourism: Three research propositions. Annals of Tourism Research, 72(C), 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharia, M., & Sitchinava, T. (2023). The importance of the transdisciplinary approach for sustainable tourism development. Georgian Geographical Journal, 3(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifolo, P. P. S. (2023a). Digital technology adaptability: Insights from destination network practices for tourism businesses in South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 12(4), 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifolo, P. P. S. (2023b). Exploring digitalization within the tourism supply chain network. IJEBD (International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Business Development), 6(3), 560–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, N. (2012). Using complexity theory to develop an understanding of tourism and the environment. In The routledge handbook of tourism and the environment (pp. 84–93). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Suk, K., Yoon, S. O., Lichtenstein, D. R., & Song, S. Y. (2010). The effect of reference point diagnosticity on attractiveness and intentions ratings. Journal of Marketing Research, 47(5), 983–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschanz, L., Arlot, M. P., Philippe, F., Vidaud, L., Morin, S., Maldonado, E., George, E., & Spiegelberger, T. (2022). A transdisciplinary method, knowledge model and management framework for climate change adaptation in mountain areas applied in the Vercors, France. Regional Environmental Change, 22(1), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Breda, A. D. P., & Pinkerton, J. (2020). Raising African voices in the global dialogue on care-leaving and emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 8(1), 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Breda, J. R. (2019). Methodological agility in the Anthropocene: An emergent, transformative transdisciplinary research approach [Doctoral dissertation, Stellenbosch University]. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vienni Baptista, B., Fletcher, I., Maryl, M., Wciślik, P., Buchner, A., Lyall, C., Spaapen, J., & Pohl, C. E. (2020). SHAPE-ID: Shaping interdisciplinary practices in Europe: Deliverable 2.3: Final report on understandings of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research and factors of success and failure (Vol. 500). ETH Zurich. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Z., Du, Q., Ma, Y., & Fan, W. (2017). A comparative analysis of major online review platforms: Implications for social media analytics in hospitality and tourism. Tourism Management, 58, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., & Tavitiyaman, P. (2022). E-Supply Chain Management in Tourism Destinations. In Handbook of e-tourism (pp. 1289–1309). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).