An Examination of the Elements of Cultural Competence and Their Impact on Tourism Services: Case Study in Quintana Roo, Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Characteristics of the International Tourism Service Provider

2.2. Approach to Intercultural Empathy

2.3. Elements of Cultural Intelligence

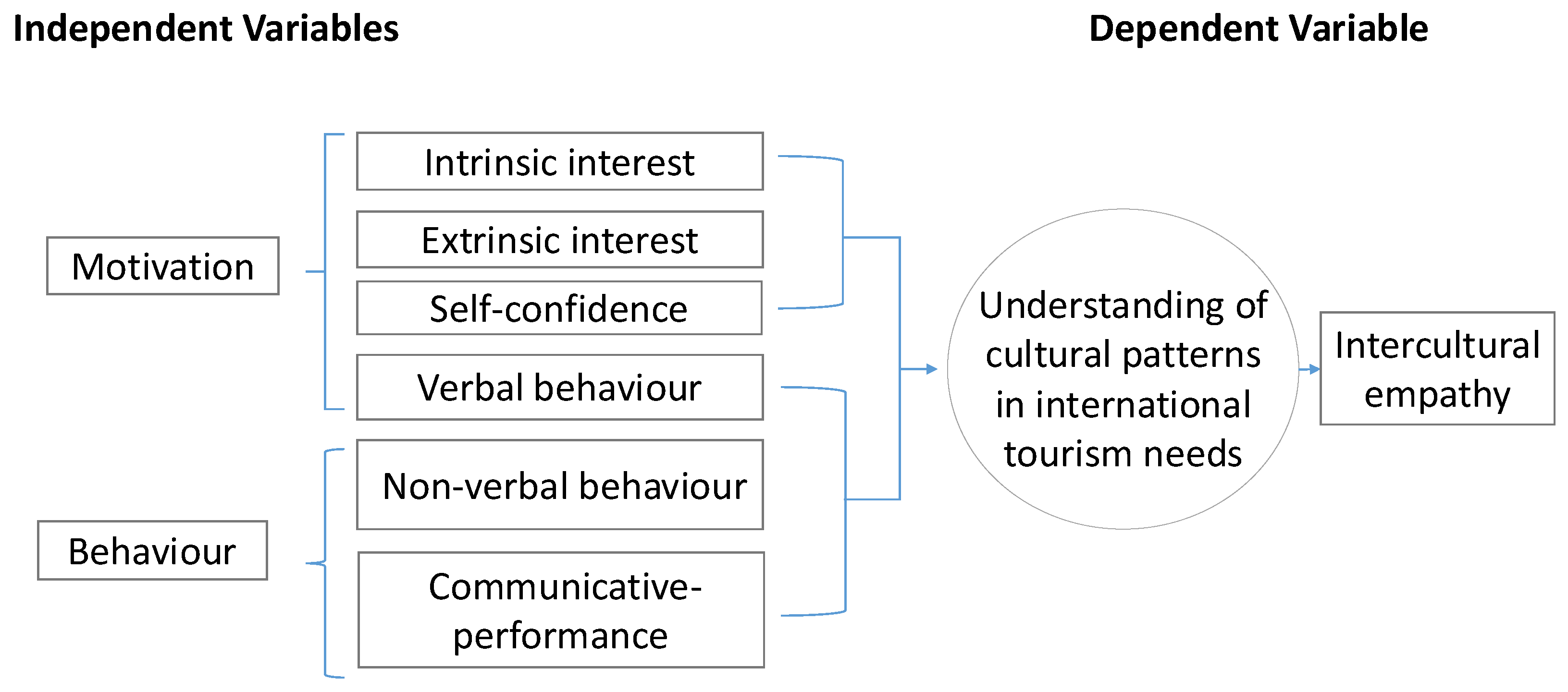

2.4. Motivation and Cultural Behaviour in Tourism Service

3. Methodology

3.1. Statistical Methods

3.1.1. Multiple Correspondence Analysis

3.1.2. Ordinal Logistic Regression

3.2. Sampling Design

3.2.1. Population

3.2.2. Sample Size

3.2.3. Statistical Analyses

Multiple Correspondence Analysis

Ordinal Logistic Regression Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analyses

4.1.1. Motivation of Cultural Intelligence

4.1.2. Cultural Intelligence Behaviour

4.1.3. Intercultural Empathy

4.2. Multiple Correspondence Analysis

4.3. Ordinal Logistic Regression Analysis

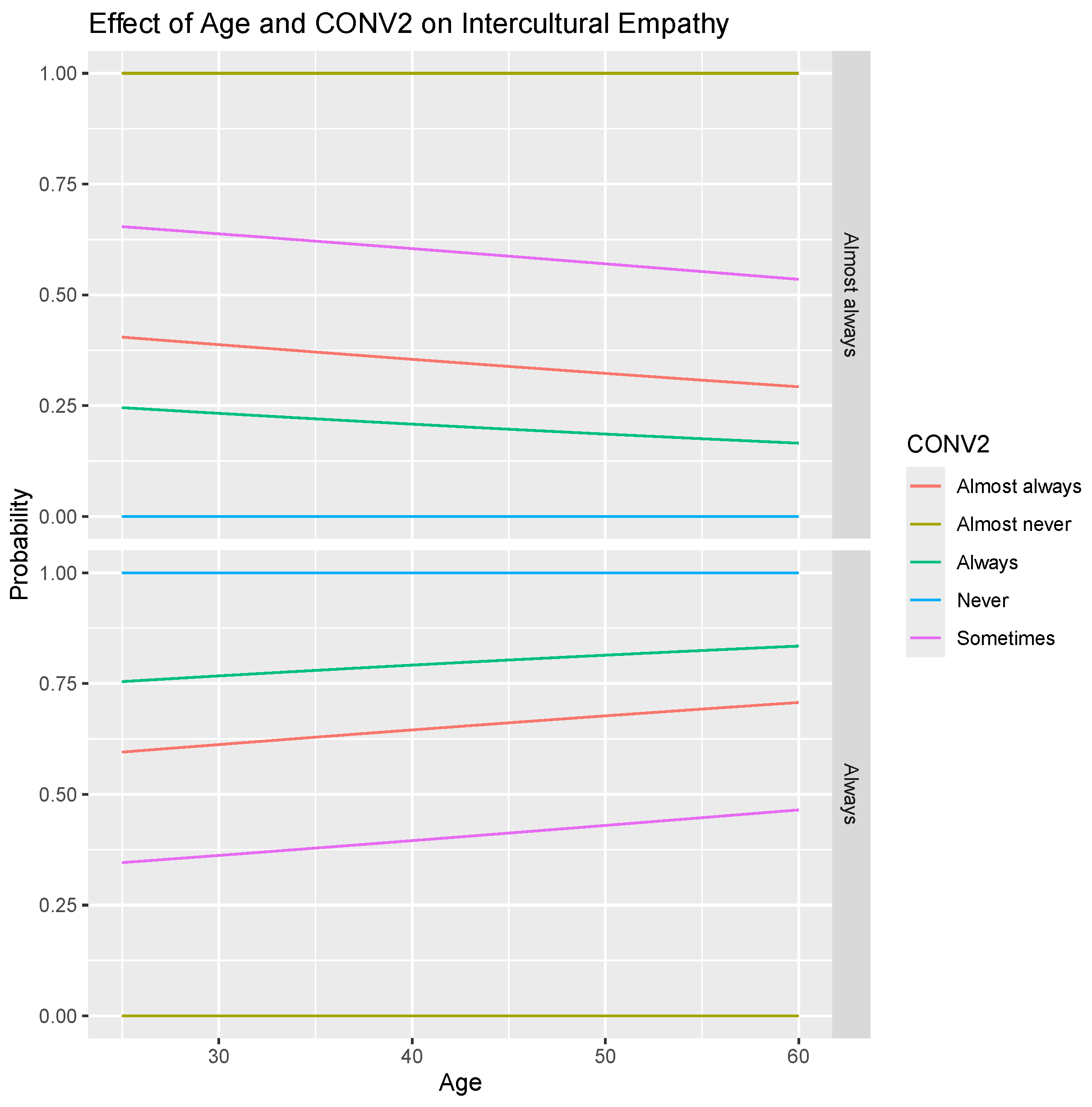

4.3.1. Intercultural Empathy, Age, and CONV2 (I Understand and Express Myself Non-Verbally with People from Other Cultures)

Probability Predictions

Odds Ratio Interpretation

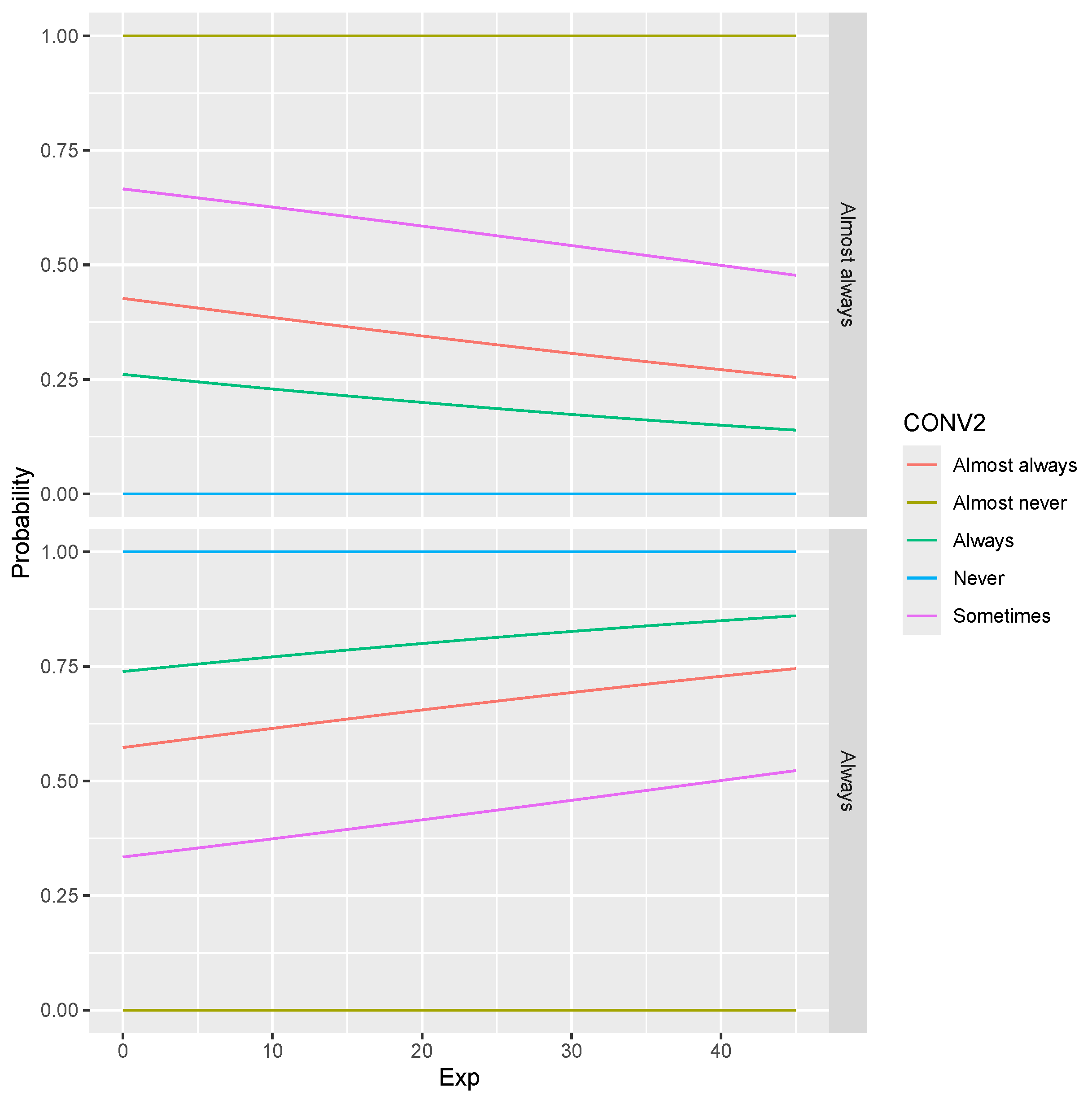

4.3.2. Intercultural Empathy, Experience, and CONV2: (I Understand and Express Myself Non-Verbally with People from Other Cultures)

Probability Predictions of the Model

Odds Ratio Interpretation

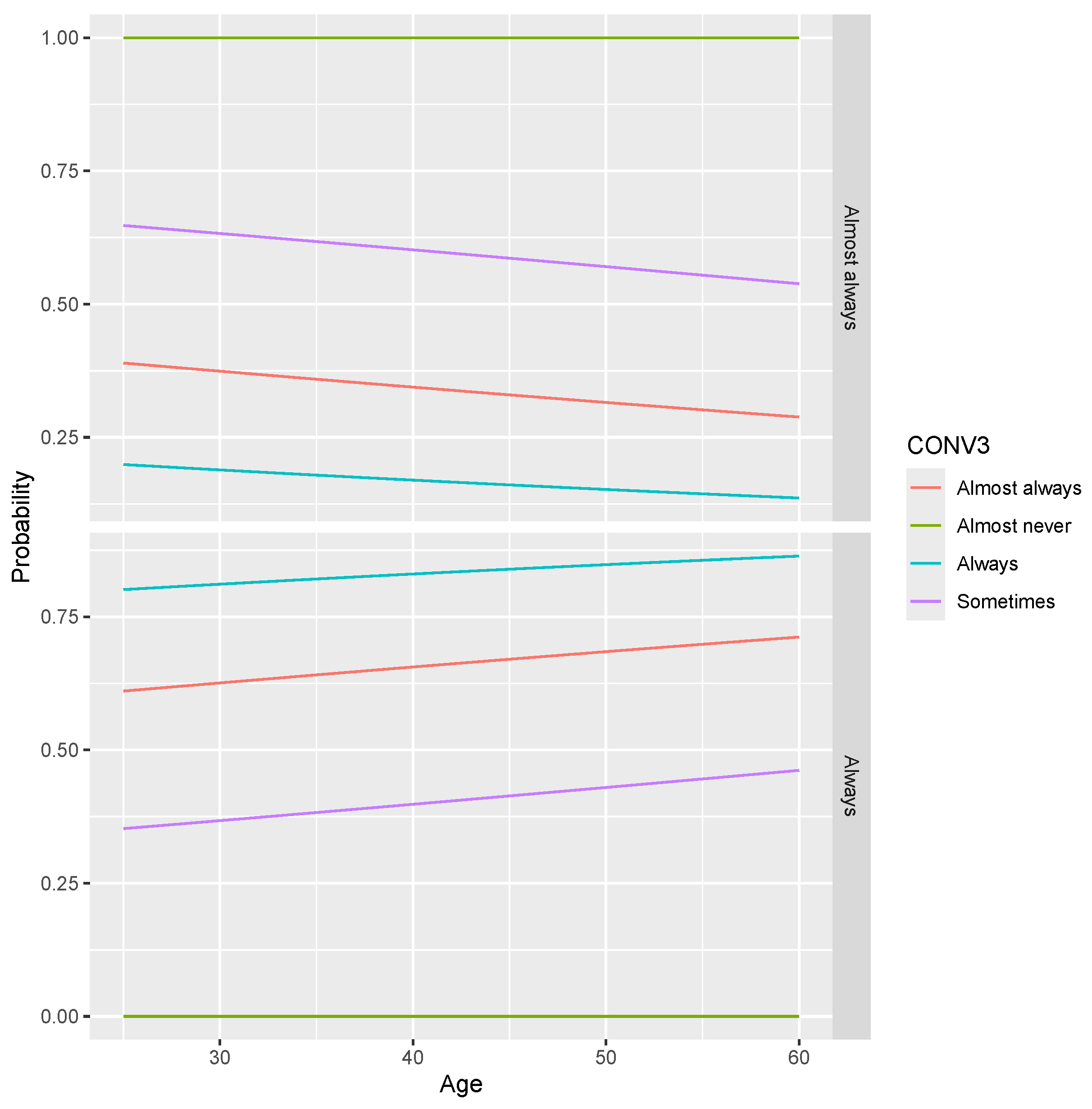

4.3.3. Intercultural Empathy, Age, and CONV3 (I Appropriately Interpret the Expressions and Behaviour of People from Other Cultures)

Probability Predictions of the Model

Odds Ratio Interpretation

4.3.4. Intercultural Empathy, Experience, and CONV3 (I Appropriately Interpret the Expressions and Behaviour of People from Other Cultures)

Probability Predictions of the Model

Odds Ratio Interpretation

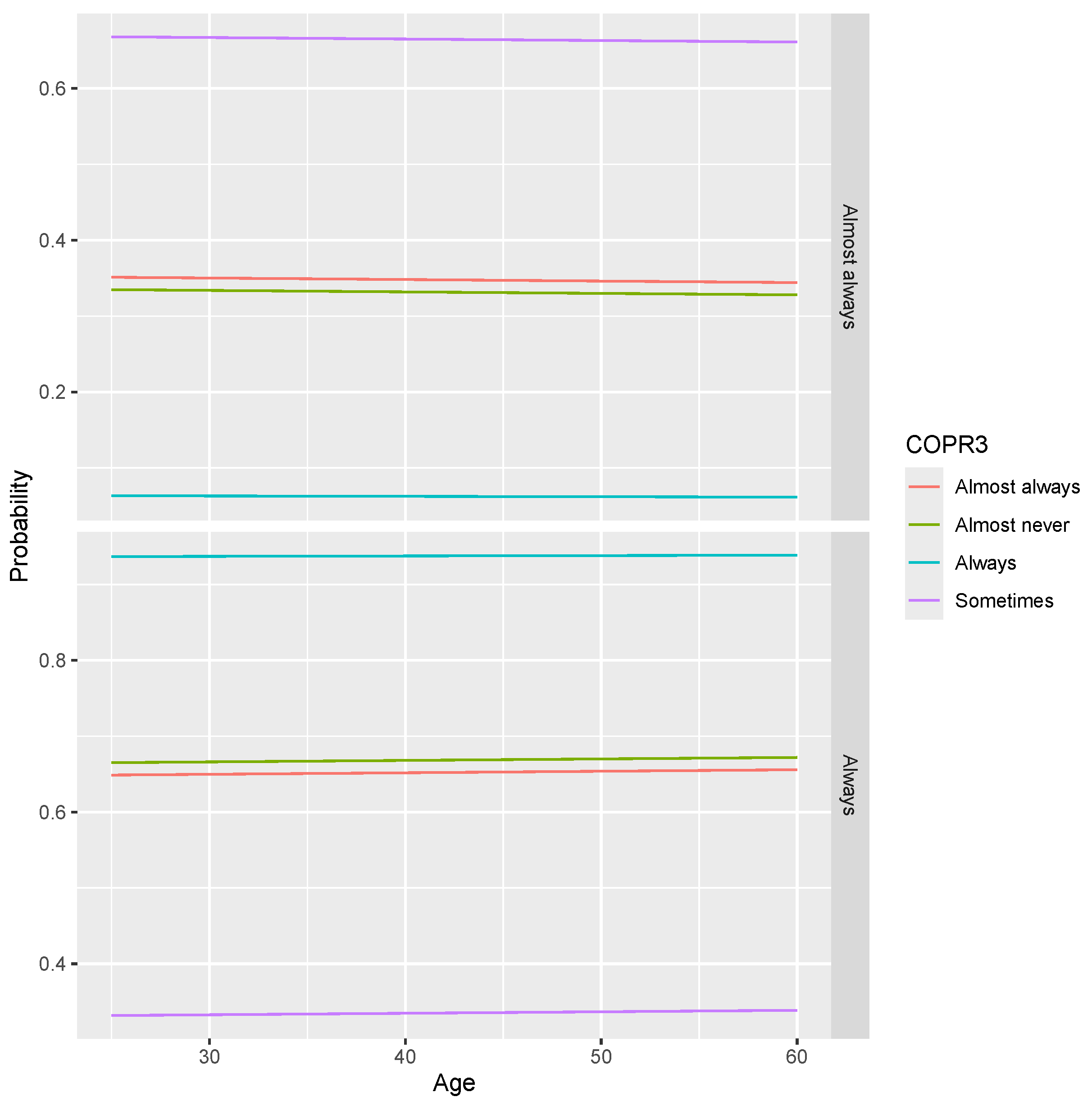

4.3.5. Intercultural Empathy, Age, and Copr3 (I Modify My Disagreements to Fit the Cultural Environment)

Probability Predictions of the Model

Odds Ratio Interpretation

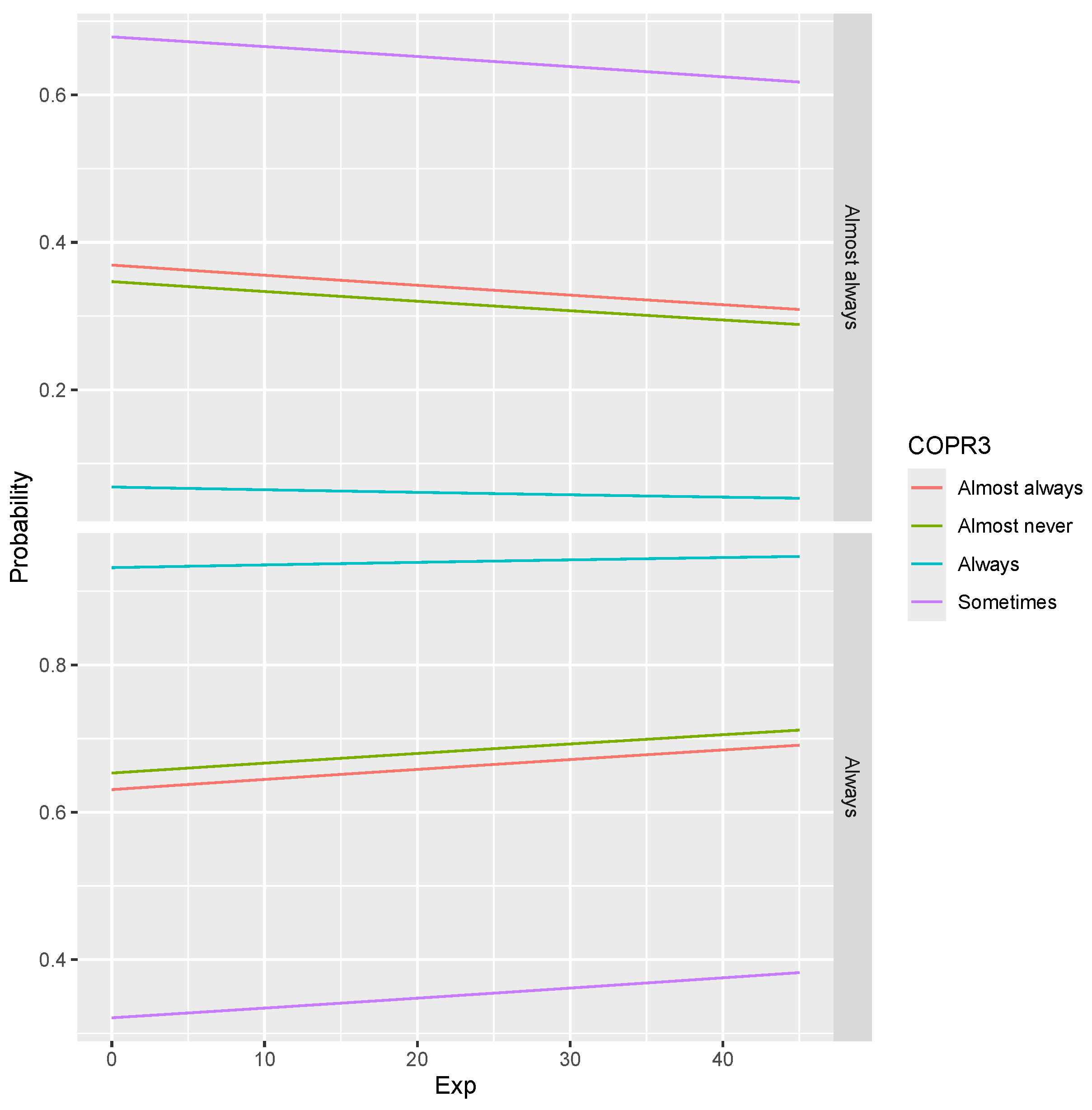

4.3.6. Intercultural Empathy, Experience, and COPR3 (I Modify My Disagreements to Fit the Cultural Environment)

Probability Predictions of the Model

Odds Ratio Interpretation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Recomendations

Managerial Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IE | Intercultural empathy |

| CQ | Cultural quotient |

| MO | Motivational cultural intelligenge |

| MOIE | Motivational cultural intelligence, extrinsic interest |

| MOII | Motivational cultural intelligence, intrinsic interest |

| MOAU | Motivational cultural intelligende, adaptative self-efficacy |

| CO | Behaviour cultural intelligence |

| COCV | Behaviour cultural intelligence, verbal behaviour |

| CONV | Behaviour cultural intelligence, non-verbal behaviour |

| COPR | Behaviour cultural intelligence, communicative performance |

| MCA | Multiple Correspondence Analysis |

| OLR | Ordinal logistic regression |

References

- Abdullah, A. A., & Haan, M. H. (2012). Internal success factor of hotel occupancy rate. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(22), 8. [Google Scholar]

- Aboud, F. E., & Levy, S. R. (2013). Interventions to reduce prejudice and discrimination in children and adolescents. In Reducing prejudice and discrimination (pp. 269–293). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Agresti, A. (2010). Analysis of ordinal categorical data. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, F., Danieli, M., & Riccardi, G. (2018). Annotating and modeling empathy in spoken conversations. Computer Speech & Language, 50, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiero, P., & Matricardi, G. (2013). Empathy towards people of different race and ethnicity: Further empirical evidence for the scale of ethnocultural empathy. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37(5), 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaibani, E., & Bakir, A. (2017). A reading in cross-cultural service encounter: Exploring the relationship between cultural intelligence, employee performance and service quality. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 17(3), 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, S., & Van Dyne, L. (2015). Handbook of cultural intelligence: Theory, measurement, and applications. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, S., Van Dyne, L., Koh, C., Ng, K. Y., Templer, K. J., Tay, C., & Chandrasekar, N. A. (2007). Cultural intelligence: Its measurement and effects on cultural judgment and decision making, cultural adaptation and task performance. Management and Organization Review, 3(3), 335–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjona Granados, M. d. P. (2021). Factores de la inteligencia cultural que promueven la empatía intercultural de los proveedores de servicios con el turismo internacional en quintana roo [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. [Google Scholar]

- Arjona Granados, M. d. P. (2022). La incidencia de empatía intercultural en hombres y mujeres que laboran en agencias de viajes en Nuevo León. Turismo y Sociedad, 30, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjona Granados, M. d. P. (2024). Relevancia de la inteligencia cultural en la calidad en el servicio al turismo internacional. Revista de El Colegio de San Luis, 14(25), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, P., & Rohmetra, N. (2010). Cultural intelligence: Leveraging differences to bridge the gap in the international hospitality industry. International Review of Business Research Papers, 6(5), 216–234. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, P., & Rohmetra, N. (2012). Cultural intelligence and customer satisfaction: A quantitative analysis of international hotels in India. Revista de Management şi Inginerie Economică, 11(1), 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur, W., Jr., & Bennet, W., Jr. (1995). The International Assignee: The relative importance of factors perveives to contribute to success. Personnel Psychology, 48(1), 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belacchi, C., & Farina, E. (2012). Feeling and thinking of others: Affective and cognitive empathy and emotion comprehension in prosocial/hostile preschoolers. Aggressive Behavior, 38(2), 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benatuil, D., & Laurito, M. J. (2011, November 22–25). Inteligencia cultural y personalidad. Análisis de las relaciones entre los constructos. III Congreso Internacional de Investigación y Práctica Profesional en Psicología XVIII Jornadas de Investigación Séptimo Encuentro de Investigadores en Psicología del MERCOSUR, Buenos Aires, Argentina. [Google Scholar]

- Bertram, D. (2008). Likert scales… are the meaning of life. Topic report. Available online: http://poincare.matf.bg.ac.rs/~kristina/topic-dane-likert.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Bhaskar-Shrinivas, P., Harrison, D. A., Shaffer, M. A., & Luk, D. M. (2005). Input-based and time-based models of international adjustment: Meta-analytic evidence and theoretical extensions. Academy of Management Journal, 48(2), 257–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobanovic, M. K., & Grzinic, J. (2019). Teaching tourism students with cultural intelligence. UTMS Journal of Economics, 10(1), 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bostjancic, E. (2010). Personality, job satisfaction, and performance of slovenian managers-how big is the role of emotional intelligence in this? Studia Psychologica, 52(3), 207. [Google Scholar]

- Broome, B. (2015). Empathy. In The SAGE encyclopedia of intercultural competence (Vol. 2, pp. 287–290). Intercultural Communication Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Bücker, J. J., Furrer, O., Poutsma, E., & Buyens, D. (2014). The impact of cultural intelligence on communication effectiveness, job satisfaction and anxiety for Chinese host country managers working for foreign multinationals. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(14), 2068–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-M., & Starosta, W. J. (2000). The development and validation of the intercultural sensitivity scale. Human Communication, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.-P., Liu, D., & Portnoy, R. (2012). A multilevel investigation of motivational cultural intelligence, organizational diversity climate, and cultural sales: Evidence from US real estate firms. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K. H.-L., & Murrmann, S. K. (2006). Development and validation of the hospitality emotional labor scale. Tourism Management, 27(6), 1181–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejo de Ministros de Europa. (2009). Libro blanco sobre el diálogo intercultural: “Vivir juntos con igual dignidad”. Ministerio de Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Monroy, L. G., & Morales-Rivera, M. A. (2012). Análisis estadístico de datos multivariados. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- Doxey, G. V. (1975, September 8–11). A causation theory of visitor-resident irritants: Methodology and research inferences. Travel and Tourism Research Associations Sixth Annual Conference Proceedings, San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Earley, P. C. (2002). Redefining interactions across cultures and organizations: Moving forward with cultural intelligence. Research in Organizational Behavior, 24, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, P. C., & Ang, S. (2003). Cultural intelligence: Individual interactions across cultures. Stanford Business Books. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Guitart, M., Rivas Damián, M. J., & Pérez Daniel, M. R. (2012). Empatía y tolerancia a la diversidad en un contexto educativo intercultural. Universitas Psychologica, 11(2), 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frías-Jamilena, D. M., Sabiote-Ortiz, C. M., Martín-Santana, J. D., & Beerli-Palacio, A. (2018). Antecedents and consequences of cultural intelligence in tourism. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M., & De Galdeano García, P. (2006). Empatía en niños de 10 a 12 años. Psicothema, 18(2), 180–186. [Google Scholar]

- Garaigordobil, M., & Maganto, C. (2011). Empatía y resolución de conflictos durante la infancia y la adolescencia: Empathy and conflict resolution during infancy and adolescence. Revista latinoamericana de psicología, 43(2), 255–266. [Google Scholar]

- García, M. O., de la O, I. L. R., & González, C. V. (2017). Tendencias del turismo hasta 2030. Contrastes entre lo internacional y lo nacional. In M. G. N. lo Andreu, & A. F. Barnet (Eds.), Anudar red. temas pendientes y nuevas oportunidades de cooperación en turismo (pp. 102–128). Publicacions Universitat Rovira i Virgili. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Martínez, A. B. (2019). Empathy for social justice: The case of Malala Yousafzai. Journal of English Studies, 17, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremani, D. G., Monterosso, J., Jentsch, J. D., Bilder, R. M., & Poldrack, R. A. (2009). Neural components underlying behavioral flexibility in human reversal learning. Cerebral Cortex, 20(8), 1843–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudykunst, W. B. (2003). Cross-cultural and intercultural communication. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, J. D., Singh, T., Weilbaker, D. C., & Guesalaga, R. (2011). Cultural intelligence in cross-cultural selling: Propositions and directions for future research. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 31(3), 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haros Pérez, J. M., & Mata Sánchez, G. A. (2021). La inteligencia cultural como elemento de la diplomacia corporativa. 3C Empresa. Investigación y Pensamiento Crítico, 10(2), 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L. C. (2012). ‘Ripping off’ tourists: An empirical evaluation of tourists’ perceptions and service worker (mis)behavior. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 1070–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L. C., & Goode, M. M. (2004). The four levels of loyalty and the pivotal role of trust: A study of online service dynamics. Journal of Retailing, 80(2), 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearns, N., Devine, F., & Baum, T. (2007). The implications of contemporary cultural diversity for the hospitality curriculum. Education+ Training, 49(5), 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J. K., Jogaratnam, G., & Buchanan, P. (2004). Customer-focused adaptation in New York City hotels: Exploring the perceptions of Japanese and Korean travelers. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 23(1), 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture and organizations. International Studies of Management & Organization, 10(4), 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind: Intercultural cooperation and its importance for survival. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, A. (2002). Font office operations and management. Thomson Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, R., & Jain, S. (2005). Towards relational exchange in services marketing: Insights from hospitality industry. Journal of Services Research, 5(2), 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Javidan, M., Teagarden, M., & Bowen, D. (2010). Making it overseas. Harvard Business Review, 88(4), 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2006). Development and validation of the basic empathy scale. Journal of Adolescence, 29(4), 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal, M. A., & Jacob, M. (2019). Cross-cultural training and cultural intelligence of hospitality students: A case study in Egypt and Spain. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 19(3), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A., & Mundt, F. (2016). Factoextra: Extract and visualize the results of multivariate data analyses. CRAN: Contributed Packages. [Google Scholar]

- Kealey, D. J., & Protheroe, D. R. (1996). The effectiveness of cross-cultural training for expatriates: An assessment of the literature on the issue. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 20(2), 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinbaum, D. G., Dietz, K., Gail, M., Klein, M., & Klein, M. (2002). Logistic regression. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, M. L., Hall, J. A., & Horgan, T. G. (1972). Nonverbal communication in human interaction. Thomson Wadsworth. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C.-M., Chen, L.-C., & Lu, C. Y. (2012). Factorial validation of hospitality service attitude. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(3), 944–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, R., Cheung, C., & Lugosi, P. (2022). The impacts of cultural intelligence and emotional labor on the job satisfaction of luxury hotel employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 100, 103084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, V. (2021). The relationship of team cultural intelligence, language Proficiency, team trust, transformational leadership and team creativity in global virtual teams [Master’s thesis, Faculteit der Managementwetenschappen]. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, G. P., & Locke, E. A. (2007). New developments in and directions for goal-setting research. European Psychologist, 12(4), 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. J., Crawford, A., Weber, M. R., & Dennison, D. (2018). Antecedents of cultural intelligence among american hospitality students: Moderating effect of ethnocentrism. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 30(3), 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê, S., Josse, J., & Husson, F. (2008). FactoMineR: An R package for multivariate analysis. Journal of Statistical Software, 25(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E., & Noriega, P. (2007). The need for leadership support in cross-cultural diversity management in hospitality curriculums. Consortium Journal of Hospitality & Tourism, 12(1), 65. [Google Scholar]

- Ljubica, J., & Dulcic, Z. (2012). The role of cultural intelligence (Cq) In the strategy formulation process–application to the hotel industry. Annals and Proceedings of DAAAM International, 23(1), 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A. M., & Etxebarria, I. (2007). La tolerancia a la diversidad en los adolescentes y su relación con la autoestima, la empatía y el concepto del ser humano. Journal for the Study of Education and Development, 30(1), 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNab, B. R., & Worthley, R. (2012). Individual characteristics as predictors of cultural intelligence development: The relevance of self-efficacy. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36(1), 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoulides, G. A., & Saunders, C. (2006). Editor’s comments: PLS: A silver bullet? MIS Quarterly, 30(2), iii–ix. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, P. F., Avery, D. R., Liao, H., & Morris, M. A. (2011). Does diversity climate lead to customer satisfaction? It depends on the service climate and business unit demography. Organization Science, 22(3), 788–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall, W., Scheaffer, R. L., & Lyman Ott, R. (2006). Elementos de muestreo. Ediciones Paraninfo S.A. [Google Scholar]

- Micó-Cebrián, P., & Cava, M.-J. (2014). Intercultural sensitivity, empathy, self-concept and satisfaction with life in primary school students/Sensibilidad intercultural, empatía, autoconcepto y satisfacción con la vida en alumnos de educación primaria. Journal for the Study of Education and Development, 37(2), 342–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinsky, A. (2007). Cross-cultural code-switching: The psychological challenges of adapting behavior in foreign cultural interactions. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 622–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P., Pritchard, M. P., & Smith, B. (2000). The destination product and its impact on traveller perceptions. Tourism Management, 21(1), 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas Cueva, A. M., Xue, J., Kuypers, T., Van Hoof, H., Panchi-Enríquez, D. E., & Caiza, R. (2024). Inteligencia cultural en el lugar de trabajo: Un estudio entre empleados ecuatorianos de primera línea. COMPENDIUM: Cuadernos de Economía y Administración, 11(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesdale, D., Griffith, J., Durkin, K., & Maass, A. (2005). Empathy, group norms and children’s ethnic attitudes. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 26(6), 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A., Pine, R., Mok, C., & Shin, J. Y. (1997). Nationality vs. industry cultures: Which has a greater effect on managerial behavior? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 16(2), 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoal, C., Eklund, J., & Hansen, E. M. (2011). Toward a conceptualization of ethnocultural empathy. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 5(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raub, S., & Liao, H. (2012). Doing the right thing without being told: Joint effects of initiative climate and general self-efficacy on employee proactive customer service performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Computer Software Manual]. The R Foundation. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Reisinger, Y., & Turner, L. (1998). Cross-cultural differences in tourism: A strategy for tourism marketers. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 7(4), 79–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley, C. R., & Lingle, D. W. (1996). Cultural empathy in multicultural counseling: A multidimensional process model. In Counseling across cultures. Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Rumble, A. C., Van Lange, P. A. M., & Parks, C. D. (2010). The benefits of empathy: When empathy may sustain cooperation in social dilemmas. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(5), 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, D., Izard, C. E., & Bear, G. (2004). Children’s emotion processing: Relations to emotionality and aggression. Development and Psychopathology, 16(2), 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla-Morales, J. A., Fernández-García, F., & Legarreta-González, M. A. (2022). Determinantes del emprendimiento en estudiantes universitarios en Tamaulipas, México. NovaRua, 14(24), 8–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, M. J., Stotzer, R., & Gutiérrez, A. S. (2013). Perspective-taking and empathy: Generalizing the reduction of group bias towards Asian Americans to general outgroups. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 4(2), 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N., Suthitakon, N., Gulthawatvichai, T., & Karnjanakit, S. (2019). The circumstances pertaining to the behaviors, demands and gratification in tourist engagement in coffee tourism. Asian Interdisciplinary and Sustainability Review, 8(1), 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobalbarro-Figueroa, M. F., Legarreta-González, M. A., García-Fernández, F., Olivas-García, J. M., Carrillo-Soltero, M. E., & Guzmán-Rodríguez, A. (2020). Análisis Socioeconómico de los Pequeños Productores de Cacao en Honduras. Caso APROSACAO. CEIBA, 0848, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhir, A. (2013). Hotel front office: A training manual. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Suthatorn, P., & Charoensukmongkol, P. (2018). Cultural intelligence and airline cabin crews members’ anxiety: The mediating roles of intercultural communication competence and service attentiveness. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 17(4), 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimouri, H., Hoojaghan, F. A., Jenab, K., & Khoury, S. (2016). The effect of managers’ business intelligence on attracting foreign tourists case study. International Journal of Organizational and Collective Intelligence (IJOCI), 6(2), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesone, D. V., & Ricci, P. (2012). Hospitality industry expectations of entry-level college graduates: Attitude over aptitude. European Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 1(6), 140–149. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D. C., & Inkson, K. (2005). People skills for a global workplace. Consulting to Management, 16(1), 5. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D. C., & Inkson, K. (2007). Inteligencia cultural: Habilidades interpersonales para triunfar en la empresa global (Vol. 63). Grupo Planeta (GBS). [Google Scholar]

- Triandis, H. C. (2006). Cultural intelligence in organizations. Group & Organization Management, 31(1), 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.-H., & Lin, Y.-C. (2004). Promoting service quality in tourist hotels: The role of HRM practices and service behavior. Tourism Management, 25(4), 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuleja, E. A. (2014). Developing cultural intelligence for global leadership through mindfulness. Journal of Teaching in International Business, 25(1), 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancouver, J. B., More, K. M., & Yoder, R. J. (2008). Self-efficacy and resource allocation: Support for a nonmonotonic, discontinuous model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dyne, L., Ang, S., & Livermore, D. (2010). Cultural intelligence: A pathway for leading in a rapidly globalizing world. Leading Across Differences, 4(2), 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyne, L., Ang, S., Ng, K. Y., Rockstuhl, T., Tan, M. L., & Koh, C. (2012). Sub-dimensions of the four factor model of cultural intelligence: Expanding the conceptualization and measurement of cultural intelligence. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(4), 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oudenhoven, J. P., & Van der Zee, K. I. (2002). Predicting multicultural effectiveness of international students: The Multicultural Personality Questionnaire. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 26(6), 679–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varner, I., & Beamer, L. (2011). Intercultural communication in the global workplace. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Vlajčić, D., Caputo, A., Marzi, G., & Dabić, M. (2019). Expatriates managers’ cultural intelligence as promoter of knowledge transfer in multinational companies. Journal of Business Research, 94, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H., & Sievert, C. (2009). ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis (Vol. 10). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wilks, D., & Hemsworth, K. (2011). Soft skills as key competencies in hospitality higher education: Matching demand and supply. Tourism & Management Studies, (7), 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Yee, T. (2017). VGAM: Vector generalized linear and additive models. CRAN, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, A. (2001). Managing customer satisfaction and retention: A case of tourist destinations, Turkey. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 7(2), 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arjona-Granados, M.d.P.; Sevilla-Morales, J.Á.; Galván-Vera, A.; Legarreta-González, M.A. An Examination of the Elements of Cultural Competence and Their Impact on Tourism Services: Case Study in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020096

Arjona-Granados MdP, Sevilla-Morales JÁ, Galván-Vera A, Legarreta-González MA. An Examination of the Elements of Cultural Competence and Their Impact on Tourism Services: Case Study in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(2):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020096

Chicago/Turabian StyleArjona-Granados, María del Pilar, José Ángel Sevilla-Morales, Antonio Galván-Vera, and Martín Alfredo Legarreta-González. 2025. "An Examination of the Elements of Cultural Competence and Their Impact on Tourism Services: Case Study in Quintana Roo, Mexico" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 2: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020096

APA StyleArjona-Granados, M. d. P., Sevilla-Morales, J. Á., Galván-Vera, A., & Legarreta-González, M. A. (2025). An Examination of the Elements of Cultural Competence and Their Impact on Tourism Services: Case Study in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(2), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020096