Abstract

The level of success in tourism is gauged by several metrics; however, the most widely used is the level of tourist arrivals. However, this research answered the call for greater investigation of the impacts of qualitative factors and intangible cultural–heritage assets on destination performance. The primary research purpose was to analyze the effect of implementing a local well-being philosophy (Tri Hita Karana) on tourist revisit intentions for Bali and the mediation of destination quality and destination image. A research model was developed to examine the relationships among local wisdom (TKH), destination quality, destination image, and revisit intentions. Data were collected via a survey of 520 digital nomadic tourists and analyzed using SmartPLS 4. The results indicated that the implementation of THK positively and significantly affected revisit intentions, destination image, and destination quality. Destination image and destination quality had positive and significant effects on revisit intentions, and destination image and destination quality also significantly mediated the effect of THK implementation on revisit intentions. The findings suggested that implementing local wisdom values such as THK in the management of a destination makes visitors feel more favorably about the quality and image of the destination and they have the intention to revisit.

1. Introduction

When Bali became a tourism destination, its people continued to preserve and promote their culture while economically taking advantage of the sector. Balinese culture has become a predominant image of Bali tourism and is a competitive identity inseparable from the traditions and characteristics of local people [1,2,3]. Balinese culture treats its residents not only as objects but also as actors in tourism. The involvement of residents in tourism is strongly influenced by the values of local wisdom, including Catur Warna, Trikaya Parisudha, Tri Samaya, Sad Kerthi, and Tri Hita Karana.

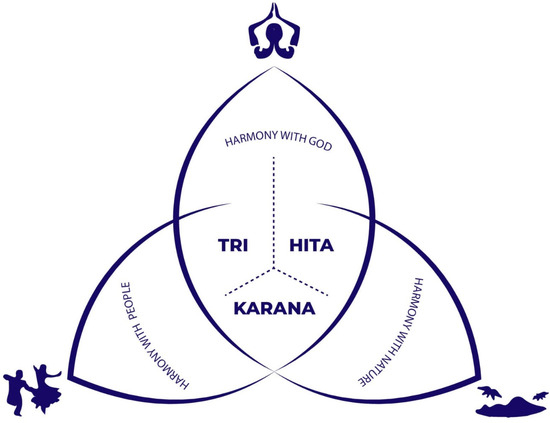

The Balinese have substantial social capital because they are supported by strong shared values, such as maintaining harmony physically and non-physically, which is contained in Tri Hita Karana (THK) or “the three causes of well-being” [4]. Social capital is one of seven components of the Community Capitals Framework (CCF), which reflects “the connections among people and organizations or the social glue to make things, positive or negative, happen” ([5], p. 21). So, in this research, the most relevant philosophy to be included that could influence destination performance was THK (Figure 1), a form of shared social capital. The THK philosophy concept was universally and globally accepted as a World Cultural Heritage in 2012, in the form of a manifestation of a cooperative social system that controls water (subak) in agriculture [6].

Figure 1.

The dimensions of Tri Hita Karana (drawing by authors).

The concept of THK is a Balinese philosophy of life. THK emphasizes three human relationships in life in this world: human relationships with God (parhyangan, spiritual), relationships with fellow humans (pawongan, social), and human relationships with the natural surroundings (palemahan, natural), with each relationship being interrelated (Figure 1). THK has become the standard in implementing tourism in Bali [7]. Empirically, several studies have revealed that the quality of destinations built from local wealth influences destination image and increases intentions to visit and revisit [8,9,10,11]. The local wealth in question is usually more directed to physical or tangible assets such as accessibility [12], supporting facilities [13], and venues for tourist activities [14]. However, aspects that are intangible, such as esthetics [15] and local cultural traditions (e.g., spiritual and religious values), may be crucial in the pursuit of sustainability [11].

The level of performance success in destination management is commonly expressed in several variables, including the amount of tourism income, employment, economic growth, competitiveness, and contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) [16]. However, the most used metric is the volume of tourists to destinations [17], especially in developing countries with limited resources and tourism facilities [18]. Qualitative indicators are seldom applied to measure success [16], which was one of the motivations for this research.

This research answered the call for more investigation of the impacts of qualitative factors and intangible assets on destination performance. The main aim was to assess the influence of a local Balinese philosophy on destination image, quality, and revisit intentions from the tourist perspective. The intended contribution of this work was to fill a literature gap regarding the influence of local cultures and beliefs on destination success. Conducting this analysis among digital nomads was expected to enhance the uniqueness of the results.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Foundations

This research was based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and the Resource-Based View (RBV). According to the TPB [19], a person visiting a destination is a behavior preceded by the intention to visit. Strong intentions were expected to exist post-pandemic when revenge tourism or “catch-up” travel would flourish [20,21]. In this research, a person’s intention to revisit Bali is assumed to be a determinant of the actual behavior. The intention is driven by attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [22]. This research measured attitudes toward the three dimensions of Tri Hita Karana and their influence on revisit intentions for Bali. In this research, attitudes toward the behavior were assumed to be personal attitudes toward the THK well-being philosophy; perceptions about how others value or regard THK were taken as subjective norms; and revisit intention represented behavioral control.

The Resource-Based View (RBV) [23,24,25] is about how managers employ resources to achieve and sustain competitive advantage and “posits that some tangible and intangible resources have certain qualities that make them the mainspring of such an advantage” ([26], p. 1842). Therefore, local wisdom was proposed as an intangible resource that could create a competitive advantage for Bali as a destination. The RBV is especially relevant in this context for Bali as TKH is a resource that is unique among its competitive destinations and can be used for differentiation.

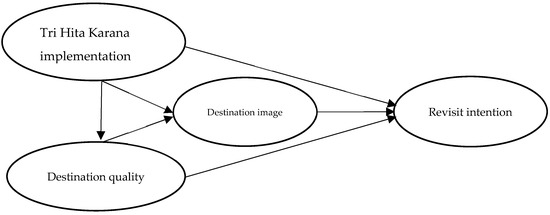

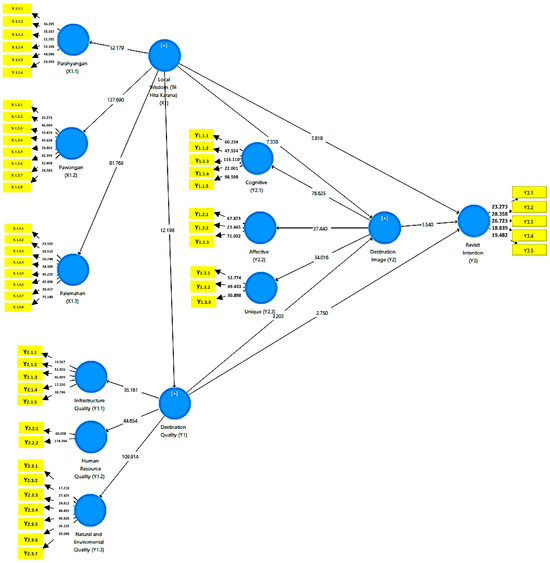

This research developed a model with destination image and destination quality as mediators of revisit intentions based on THK implementation. The model analyzed (Figure 2 and Figure 3) incorporates the TBP and RBV, and previous research has yet to conduct an effect analysis with this model and these variables.

Figure 2.

Conceptual research model.

Figure 3.

Bootstrapping model.

2.2. Local Wisdom

Improving the performance and competitiveness of a destination is achieved through effective management and marketing [17,27]. The better the performance of a destination, the higher the tendency for tourists to return [28]. Appropriately managed resources reinforce the management of a destination and its marketing and can even become a strong motivator for people to return. Local resources are tangible and intangible, and the two categories can be used to improve destination performance.

Local wisdom is expected to have a role in optimizing the performance of destinations to produce quality tourism [29,30,31] and a positive destination image [32]. Quality tourism destinations are not only expected to enhance their images by deploying local wisdom, but they can also positively advance sustainable tourism goals.

A theme that is part of local wisdom in the form of life experience values [32], environmental values [10,33], and local community social values [34,35] can make a destination unique and difficult to imitate [36,37]. This inimitability can become a sustainable competitive advantage fulfilling the expectations of tourists [38,39], keeping the destination sustainable, and increasing revisit intentions [9,40,41,42].

The research on the influence of destination image on visit intentions has produced different results. Destination image positively influences destination selection [34,43]. Cognitive, affective, and conative images of the destination can also have varying influences [44,45]. Other studies show that destination image influences the behavior of tourists who travel to destinations [39,46,47,48], especially those destinations that embed themes of culture and history [49]. Also, destination images can negatively affect behavior in choosing destinations [50].

This analysis is different from previous research by engaging the local wisdom construct. The work integrates local wisdom’s influence on tourism destinations’ image and quality as mediators of the intentions for repeat visits. Through conducting expert interviews and focus groups, it also provides a vetted set of indicator items for measuring the integration of THK in tourism.

2.3. Digital Nomads

Since 2018, the Indonesian Ministry of Tourism has opened greater space for digital nomads as one of the markets to accelerate the growth rate in tourist visits [51]. Digital nomads have a lifestyle of moving from one destination to another, with extended stays compared to tourists in general [52]. While working online, they continue to enjoy the products offered at the places they visit and seek services and travel experiences in each destination [53,54,55,56]. These individuals usually frequent local coworking spaces that provide convenient workstations and Internet network services [56,57]. Like other visitors, they expect to participate in unique and memorable experiences during their stays [58].

This research selected respondents who qualified as digital nomadic tourists. They were chosen because research on revisit intentions in the business literature and tourism management generally does not distinguish between specific types of tourists. The advantages of digital nomadic tourists for this specific research topic were that their lengths of stay are longer than other tourist groups, and these individuals have a tendency to be closer to the community and local values of the destinations they visit [53,55,56].

2.4. Local Wisdom and Revisit Intentions

The intention to visit a destination is a popular research topic. Visit intentions are influenced by several factors, including the quality of destinations [59,60,61,62,63] and destination images [37,39,64,65,66,67,68,69]. Through quality and positive images, destinations will become more desirable places to visit (destination competitiveness), which can play an essential role in attracting tourists. How substantial the intention to visit a destination is greatly influenced by how well the destination builds and communicates its image and how well the quality of the destination fulfills the expectations and needs of tourists. A compelling destination image can become the identity (brand) of the destination [70].

Local wisdom, such as THK, can affect tourist satisfaction [71]. Previous research shows that emotional attachment to a destination significantly influences individuals to visit [72] when its elements positively impact the environment [33,41,42]. Likewise, a destination that provides authentic experiences with new and potentially transformational insights [73] and experiences of lifestyle and habits can motivate people to visit [10]. Therefore, the following was hypothesized:

H1.

THK implementation positively and significantly affects revisit intentions.

2.5. Local Wisdom and Destination Image

A destination should satisfy a person’s needs, which is critical in creating the desire to travel there [74]. People are influenced by several factors in making travel decisions, including how the destination communicates its attractions and experiences [75]. Management that promotes environmental friendliness and the social–cultural pillar of sustainable development can generate a competitive advantage [29,30], as well as have a positive influence on the image of the tourism sector [32]. Destination managers utilize many factors to build positive images. Research shows that the marketing of destinations prioritizing environmentally friendly aspects impacts the image of the tourism sector and destination images [76]. Various components of a destination, cognitively and affectively, can also affect the image of a destination [77]. When the stakeholders of a destination adopt and embody its unique identity, this affects the image of the destination [10]; therefore, the following was hypothesized:

H2.

THK implementation positively and significantly affects destination image.

2.6. Local Wisdom and Destination Quality

The favorable quality of destinations positively impacts visit intentions [15]; however, the effect can be harmful if the value obtained by tourists is less than expected [78]. The quality of tourism destinations affects repeat visit intentions [12]. The results of previous studies show that a lack of quality negatively impacts visit intentions [79]. The quality of environmentally friendly destinations can have a direct positive influence [8,9,11] and also function indirectly [13,80]. This justifies the integration of the dimensions of the quality of destinations on visit intentions in a research model.

More in-depth awareness of the attractiveness of a destination positively influences intentions to visit [81,82,83,84]. Associations gained in the form of culture, history, and activities affect the images of destinations [35]. Cultural and historical heritage [85], local food [86], and social and community life [87] can strongly impact visits. Some scholars have found that intangible elements have a more substantial influence than tangible ones [88,89].

Good management delivers greater efficiency [90] and can improve quality and competitive advantage [29,30]. Tourism development based on local wisdom can also do so [91,92]. Local values may also enhance business performance [93,94], and connecting visitors with local communities elevates the interests of local residents and makes destinations more sustainable [31,95,96,97,98]; then, the following was hypothesized:

H3.

THK implementation positively and significantly affects destination quality.

2.7. Destination Quality and Destination Image

The image of a tourism destination can be built on local wisdom through what is owned collectively by residents and other stakeholders [18]. Destinations that maintain good-quality natural resources can become the preferred choices of tourists [99], as well as the quality of local food offered. If a destination’s image is built on its quality, this may positively influence visits to that destination [33,41]. Appropriate quality management of destinations builds more attractive destination images [37,38,100,101], so the following was hypothesized:

H4.

Destination quality positively and significantly affects destination image.

2.8. Destination Image and Revisit Intentions

Organizations with favorable reputations attract consumer transactions [102]. A strong image influences a person’s purchase [32]. Positive destination images beneficially affect destination selection and visit intentions [76,77,103,104,105,106,107,108]; hence, the following was hypothesized:

H5.

Destination image positively and significantly affects revisit intentions.

2.9. Destination Quality and Revisit Intentions

Multiple factors affect destination selection. These include destination competitiveness, the life cycle stage [109], and internal and external factors, including all destination attributes [110]. Familiarity and a sense of authenticity may pique the desire to visit [41,72,111,112]. Perceived destination quality is another influential factor [9,40,113]; hence, the following was hypothesized:

H6.

Destination quality positively and significantly affects revisit intentions.

2.10. Mediation by Destination Image

The image of a destination can be established around the values of people’s lives or local wisdom [114]. A destination that previously had a negative image [31], when supported by good environmental values [115] and the life experiences gained by tourists while visiting, may be able to achieve an image change [71], and increase intentions to visit [10]. However, negative values in a society may have the opposite effect and deter visits [116]. The following was hypothesized:

H7.

Destination image positively and significantly mediates THK implementation on revisit intentions.

2.11. Mediation by Destination Quality

In addition to having the essential components, the management of a good destination must also be built on the values the destination possesses [117]. The quality of destinations based on the values of local communities or local wisdom can impact increasing tourist visits [118]. The quality of destinations built upon local wealth has the potential to increase return visits [8,9,10,11,12,71]. However, the intangible dimensions for the quality of tourism destinations [15] need to be specified in greater detail, including the dimensions of THK. The following was hypothesized:

H8.

Destination quality positively and significantly mediates THK implementation on revisit intentions.

3. Methodology

The implementation of THK involves the values of harmonious human relationships in life as measured by three dimensions, namely parhyangan, or the relationship between humans and God, pawongan, or the relationship between fellow humans, and palemahan, or the relationship between humans with the environment and the natural surroundings [119]. This research used a mixed-method research design. Firstly, the three dimensions of THK, consisting of 22 indicator items (Appendix A), were obtained through an approach suggested by [120], namely from literature analysis, in-depth interviews with 21 experts, and group discussion forums (FGDs). The experts included were selected from all stakeholders who fully understand the culture and development of tourism in Bali. They were individuals from academia, government agencies, community leaders, industry, and media. Secondly, a survey of digital nomads staying in Bali was conducted. The surveys were conducted from May 2022 to August 2023. They were administered face-to-face with digital nomads at their accommodations by trained research staff.

Destination image is the perception of the image of destinations, measured by three dimensions: cognitive, affective, and unique [67,68]. Appendix B.2.2 shows five measurement items in the survey for cognitive image; three for affective image; and three for unique image.

Destination quality is the perception of quality in tourism destinations. Based upon previous research in tourism, destination quality was measured by three dimensions: infrastructure quality (five items), human resource quality (two items), and natural and environmental quality (seven items) (Appendix B.2.3) [63].

Revisit intention represents a person’s intention to return to a destination. Five items derived from previous research were used to measure revisit intentions (Appendix B.2.4).

The survey respondents were digital nomadic tourists residing in the Canggu, Seminyak, and Ubud tourism areas. A total of 600 questionnaires were administered face-to-face with people who were qualified as digital nomadic tourists. After removing invalid and incomplete forms, 520 remained (response rate of 86.7%).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.1.1. Respondent Characteristics

Appendix B.1 contains the results for 15 respondent characteristics. It is of particular interest to this research topic that most respondents (99%) knew about THK.

4.1.2. Measurement Item Ranking

The overall mean scores for all four variables were high—THK implementation (M = 4.40), destination image (M = 4.47), destination quality (M = 4.40), and revisit intentions (M = 4.53) (Appendix B.2.1–B.2.4). The highest individual mean item scores were for the following: I will recommend Bali to others (M = 4.66, revisit intentions); unique cultural diversity (M = 4.54, destination image); easy to get food and drinks (M = 4.48, destination quality); and upholding the diversity of religions and beliefs (M = 4.52, THK implementation).

4.2. Common Method Bias (CMB) Test

Since a cross-sectional design was used, Harman’s single-factor test [121] was employed to check for the common method bias (CMB) issue. The variance explained by the first factor was 27.88%, which was below the maximum threshold of 40%, thus confirming that CMB was not a concern in this research.

4.3. Assessment of Measurement Model

The measurement of the evaluation of the model (outer model) was carried out to determine the influence between latent variables (constructs) and indicator items (observed variables). The load factors determined the convergent validity of THK implementation, and all indicator item load factors were greater than 0.6 (Appendix B.3), meeting the requirements of convergent validity. Convergent validity testing is also performed by examining each latent variable’s average variance extracted (AVE) value, and it is recommended that the AVEs should be greater than 0.50 [122]. The results showed that all variables had AVEs greater than 0.5 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Construct reliability and validity.

All constructs and their components had Cronbach’s alphas and composite reliability (CR) values greater than 0.7 (Table 1), meaning that all dimensions and variables met the requirements for composite reliability. The r-square for destination image was 0.431, meaning that THK implementation influenced 43.1% of destination image and quality. The r-square for revisit intention was 0.215, implying that the THK implementation, destination quality, and destination image influenced 21.5% of revisit intention.

Discriminant validity is met if the square roots of the AVEs in the Fornell–Larcker criterion table are greater than the correlations involving these latent variables [123]. This condition was met (Appendix B.4). The Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio results showed that all values were below 0.9 (Appendix B.4), so the criteria for discriminant validity were met.

4.4. Assessment of Structural Model

Variance inflation factors (VIFs) were used to assess the multicollinearity issue. The VIFs were from 1.150 to 1.757 (Appendix B.5), meeting the requirement of less than 3.33 [122]. Then, the proposed structural relationships were tested using the bootstrapping technique. The hypothesis testing was carried out after resampling bootstrapping. Hypothesis testing on the effect of THK implementation on destination quality, destination image, and revisit intentions was carried out by comparing the t-statistics and p-values and observing the sign of the original sample in the path coefficients table.

After resampling bootstrapping, the research model contained the value of t-statistics, describing the magnitude of the influence among constructs, dimensions, and indicator items in the model. The greater the value of t-statistics, the more dominant these indicators were in measuring the variables (Figure 3).

THK implementation and revisit intentions (H1): The direct effect of THK implementation on revisit intentions was significant at 2.818 (p = 0.005), supporting H1 (Table 2, Figure 3). The original sample estimate value was positive (0.154), indicating that the direction of influence between the implementation of THK on revisit intentions was positive.

Table 2.

Hypotheses tests.

THK implementation and destination image (H2): The second hypothesis stating that the implementation of THK has a positive and significant effect on the destination image was supported (t = 7.338, p = 0.000). The original sample estimate value was positive (0.338), indicating that the direction of influence between the implementation of THK and destination image was positive.

THK implementation and destination quality (H3): The third hypothesis stating that the implementation of THK has a positive and significant effect on destination quality perceived by tourists was supported (t = 12.198, p = 0.000). The original sample estimate value was positive (0.510), showing that the direction of influence between the implementation of THK on destination quality was positive.

Destination quality and destination image (H4): The fourth hypothesis stating that destination quality positively and significantly affects destination image was supported (t = 9.203, p = 0.000). The original sample estimate value was positive (0.416), indicating that the direction of influence between destination quality and destination image was positive.

Destination image and revisit intention (H5): The fifth hypothesis, stating that destination image has a positive and significant effect on revisit intention, was supported (t = 3.540, p = 0.000). The original sample estimate value was positive (0.246), showing that the direction of influence between destination image and revisit intention was positive.

Destination quality and revisit intention (H6): The sixth hypothesis that destination quality has a positive and significant effect on revisit intention was supported (t = 2750, p = 0.006). The original sample estimate value was positive (0.149), indicating that the direction of influence between destination quality and revisit intention was positive.

Destination image mediation (H7): The seventh hypothesis stating that destination image mediates the effect of THK implementation on revisit intentions was supported. The magnitude of the indirect effect of THK on revisit intention through the destination image variable was 3.266, with a p-value of 0.001 (Table 3). The original sample estimate value was positive (0.083), indicating the direction of the influence of THK’s direct implementation of revisit intention through the destination image variable is positive. The implementation of THK significantly affected revisit intention (t = 2.818, p = 0.000). THK had a significant effect on destination image (t = 7.338, p = 0.000), and destination image had a significant effect on revisit intention (t = 3.340, p = 0.000), implying that destination image mediated the effect of THK on revisit intention.

Table 3.

Mediation tests.

Destination quality mediation (H8): The eighth hypothesis stating that destination quality mediates the effect of THK implementation on revisit intentions was supported. The magnitude of the direct effect of THK on revisit intention through destination quality was 3.906 with a p-value of 0.004, and the original sample estimate value was positive (0.052), indicating the direction of the direct influence of THK implementation (Table 3). THK’s effect on revisit intention through destination quality was positive. The implementation of THK significantly affected revisit intention (t = 2.818, p = 0.005). THK had a significant effect on destination quality (t = 12.198, p = 0.000), and destination quality significantly affected revisit intention (t = 2.750, p = 0.006), suggesting that destination quality mediated the effect of THK implementation on revisit intention.

Effect sizes (f-squares) were evaluated to determine the importance of each path. The findings were that the THK implementation → revisit intention path was in the intermediate range with an f2 of 0.154; destination quality → revisit intention was in the intermediate range, f2 of 0.154; and destination image → revisit intention was also in the intermediate range, f2 of 0.246. The effect sizes for the paths of the three dimensions of THK to THK implementation had f2 from 0.855 and 0.913 (Appendix B.6).

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Through qualitative methods, this research developed indicator items for the three dimensions of THK, a local wisdom philosophy. The uniqueness and value of a culture may be used as a strategy for differentiation and sustainable competitive advantage because it contains rare ingredients that cannot be easily imitated [24]. THK values can be strategically incorporated in tourism development and marketing [124]. The three dimensions of THK implementation can be used as a guiding philosophy for tourism destination management.

Indicator items were developed for parhyangan, pawongan, and palemahan to anchor THK implementation. Destination performance measurement through revisit intentions based on local wealth, such as local wisdom, focuses on intangible assets and may more effectively support sustainable tourism [8,9,10,11]. Several studies on local wealth have been based on intangibles [15]. However, there is a need for more research on local wealth in the form of dimensions of social and spiritual/religious values that many destinations possess. Developing indicators for parhyangan, pawongan, and palemahan also uncovered potential new indicators for managing destinations.

The findings confirmed that destination image and quality were mediating variables in the effect of THK on revisit intentions. Previous research has yet to analyze this relationship in which destination image and quality are primarily measured as independent or exogenous variables.

The implementation of THK, destination image, and quality influences revisit intentions. The central factor in the TPB [22] is the individual’s intention to perform a given behavior, which is considered to capture the motivational factors that influence behavior. This indicates how hard people are willing to try and how much effort they plan to put into their behavior. The stronger the intention to engage in a behavior, the more likely it is to be performed.

The implementation of THK affecting the intention for repeat visits to Bali can be measured through the dimensions of parhyangan, pawongan, and palemahan, directly experienced by visitors. Each indicator of THK implementation supports the experiences that people receive when engaged in tourism activities, which involve direct contact with the lives of local Balinese people. This has a significant effect on increasing the intentions of tourists to return to Bali.

Destination image’s effect in increasing revisit intentions is reflected in the uniqueness of Bali as a destination. Several empirical studies state that unique tourism destinations have potential and attractions that cannot be found elsewhere. Bali has a uniqueness that is not only in the form of historical places and people, as well as its climate and natural beauty but also in its unique cultural diversity.

The quality experienced by tourists while in Bali is based on the infrastructure, human resources, nature, and the environment. A good tourism destination’s quality significantly increases tourists’ return intentions. THK can make Bali a competitive and superior tourism destination according to the Resource-Based View (RBV) theory [23]. This is especially so if the quality of the destination meets the VRIO criteria [25], namely the value of resources (value), scarcity of resources and capabilities (rarity), the possibility of being imitated (imitability), and exploitation of potential resources and capabilities by the organization (organization).

One of the primary implications of this study is that increasing revisit intentions can be achieved if the destination can integrate local wisdom, enhancing destination image and quality. The results of this research can be treated as empirical evidence on which to base future studies. They can be used as a reference in analyzing tourist behavior related to local wisdom, destination image, destination quality, and revisit intentions.

6. Managerial Implications

The respondents provided recommendations in open-ended questions regarding their impressions of Bali tourism and how it could be improved. Their commentaries were insightful in how better to implant and apply THK in future. In some cases, respondents noted contradictions between the real situation in Bali and the desired situation for the three THK dimensions.

One respondent stated that “Not many people from the outside of Bali know about Tri Hita Karana, maybe it would be better if there was some education about it”. Another added there was a “need to promote more about Tri Hita Karana” and a third suggested “more socialization of THK”. A fourth said, “I hope Bali will improve promotions about the culture especially about Tri Hita Karana” and a fifth stated, “I hope to know more about THK”. The first managerial suggestion, therefore, is that there should be more education and promotion of THK for visitors and residents.

The environment is one of the three dimensions of THK. However, several respondents wanted the environment in Bali to be cleaner and for waste management to be conducted at a superior level. “The implementation of THK should make Bali cleaner” was the view of one person. A second observed, “the community and government in Bali must pay more attention to the garbage scattered on the beach, so that Bali remains beautiful and free of waste”. Another said, “tourists and Balinese people in particular must keep the cleanliness and preservation of the natural environment”. More than 60 respondents commented without prompting about the lack of adequate cleanliness in Bali at present. The second management recommendation, thus, is that the standards of cleanliness and waste removal need to be significantly improved in Bali.

The third implication is for the need to involve Bali residents more in communicating about THK to visitors. “Hopefully local people can introduce Tri Hita Karana to tourists so they can get to know them better” was a suggestion from a respondent. Another recommended, “Give more space for community and Balinese people in THK implementation”.

Generally, visitors supported the implementation of THK, wanted it to be continued, and felt that it was appropriate for Bali. However, one expressed the feeling that “I don’t think the Tri Hita Karana concept is being applied”. While the quantitative research produced positive results about THK, there was some visitor sentiment that its implementation needed greater attention from government agencies and others involved in Bali tourism. The implication then is that a broad assessment of THK implication is needed and that its communication and interpretation require greater attention.

The basic thinking behind THK is how to maintain well-being and wellness. However, there is reason to believe from this research that this association is not well understood by Bali visitors. The final recommendation is that more communication be made connecting THK with well-being and wellness, as there is growing consumer demand for these features in tourism.

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This research has certain limitations that need to be acknowledged. THK is a local philosophy unique to Bali and could be without parallel elsewhere. This analysis should be replicated in other destinations with distinctive local wisdom and culture. The decision to survey digital nomads was made partly to reduce response variability. However, digital nomads are diverse and have different backgrounds, habits, and travel patterns. Future researchers should consider including other groups, such as Millennials and elderly tourists. It may also be advantageous to separately consider international and domestic visitors.

The respondents were highly aware of THK; however, the awareness might have been less great if all Bali tourists had been surveyed. A more random approach to sample selection should be considered to avoid this limitation in the future.

Destination performance is multidimensional and can be viewed from the perspectives of multiple stakeholders. Future research should introduce other factors apart from local wisdom, destination image, and destination quality, including tourist satisfaction and overall destination evaluation, and analyze the attitudes and opinions of other stakeholders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.K.L.; Methodology, H.K.L. and A.M.M.; Validation, A.M.M.; Formal analysis, H.K.L. and A.M.M.; Investigation, H.K.L.; Data curation, H.K.L.; Writing—original draft, A.M.M.; Visualization, A.M.M.; Supervision, N.N.K.Y., T.G.R.S. and I.P.G.S.; Project administration, N.N.K.Y., T.G.R.S. and I.P.G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the official confirmation from the Ethics Commission for Social Humanities of BRIN.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. THK Indicators

| Variable | Dimensions | Indicator items |

| Implementation of Tri Hita Karana Sources: [119,124,125,126] |

Parhyangan (Spiritual) |

|

| Pawongan (Social) |

| |

| ||

| Palemahan (Natural) |

| |

|

Source: Interviews and FGDs, 2022.

Appendix B. Descriptive Statistic Details

Appendix B.1. Respondent Characteristics

| No. | Characteristics | Levels | Persons | % |

| 1. | Origin | Indonesia | 270 | 51.92 |

| Europe | 83 | 15–96 | ||

| Australia | 60 | 11.54 | ||

| Asia | 55 | 11.58 | ||

| USA | 52 | 10.00 | ||

| Total | 520 | 100.00 | ||

| 2. | Gender | Male | 277 | 53.27 |

| Female | 243 | 46.73 | ||

| Total | 520 | 100.00 | ||

| 3. | Age | 17–30 years old | 362 | 69.61 |

| 31–50 years old | 142 | 27.30 | ||

| >50 years | 16 | 3.10 | ||

| Total | 520 | 100.00 | ||

| 4. | Education | Diploma/Bachelor | 347 | 77.73 |

| Senior high school | 96 | 18.58 | ||

| Master degree | 74 | 14.22 | ||

| Doctoral degree | 3 | 0.58 | ||

| Total | 520 | 100.00 | ||

| 5. | Occupation | Employees | 242 | 46.57 |

| Students | 130 | 25.02 | ||

| Professional | 45 | 8.72 | ||

| Government officer | 21 | 4.04 | ||

| Others | 82 | 1.85 | ||

| Total | 520 | 100.00 | ||

| 6. | Trips average per year | 2–5 times/year | 301 | 57.91 |

| Once/year | 160 | 30.82 | ||

| >5 times/year | 59 | 11.33 | ||

| Total | 520 | 100.00 | ||

| 7. | Purpose of visit | Holiday | 364 | 70.00 |

| Business | 66 | 12.69 | ||

| VFR | 52 | 10.00 | ||

| Event visit | 14 | 2.70 | ||

| Others | 24 | 4.62 | ||

| Total | 520 | 100.00 | ||

| 8. | Travel with | Family/relatives | 205 | 39.42 |

| Friends | 169 | 32.50 | ||

| Alone | 104 | 20.00 | ||

| Spouse | 42 | 8.08 | ||

| Total | 520 | 100.00 | ||

| 9. | Source information on Bali | Social media | 290 | 55.77 |

| Family/friends | 172 | 33.08 | ||

| Official website | 28 | 5.38 | ||

| Others | 30 | 5.77 | ||

| Total | 520 | 100.00 | ||

| 10. | Length of stay in Bali | 1–4 weeks | 302 | 58.08 |

| 1–3 months | 120 | 23.08 | ||

| >3 months | 98 | 18.85 | ||

| Total | 520 | 100.00 | ||

| 11. | Where staying in Bali | Canggu | 112 | 21.54 |

| Seminyak | 101 | 19.42 | ||

| Ubud | 88 | 16.92 | ||

| Sanur | 53 | 10.19 | ||

| Others | 166 | 31.92 | ||

| Total | 520 | 100.00 | ||

| 12. | Times visited Bali | 2–3 times | 221 | 42.50 |

| >3 times | 216 | 41.54 | ||

| Once | 83 | 15.96 | ||

| Total | 520 | 100.00 | ||

| 13. | Destination before Bali | Other Indonesia | 201 | 38.65 |

| Asia | 190 | 36.54 | ||

| Europe | 68 | 13.08 | ||

| Australia | 44 | 8.46 | ||

| Others | 17 | 3.27 | ||

| Total | 520 | 100.00 | ||

| 14. | Destination after Bali | Other Indonesia | 212 | 40.77 |

| Asia | 189 | 36.35 | ||

| Europe | 42 | 8.08 | ||

| Australia | 38 | 7.31 | ||

| USA | 19 | 3.65 | ||

| Others | 20 | 3.85 | ||

| Total | 520 | 100.00 | ||

| 15. | Know about Tri Hita Karana | Yes | 514 | 99.04 |

| No | 6 | 0.96 | ||

| Total | 520 | 100.00 |

Appendix B.2

Appendix B.2.1. Tri Hita Karana Implementation: Mean Item Scores

| No | Items | Respondent Ranking | Total Score | Mean Score | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||

| A. | Parhyangan (X 1.1) (Spiritual) | 4.45 | ||||||

| 1. | Take good care of places of worship (X1.1.1) | 0 | 4 | 36 | 195 | 285 | 2.321 | 4.46 |

| 2. | Upholding the diversity of religions and beliefs (X1.1.2) | 0 | 2 | 23 | 199 | 296 | 2.349 | 4.52 |

| 3. | Faithfully attend spiritual meetings (X1.1.3) | 0 | 3 | 28 | 208 | 281 | 2.327 | 4.48 |

| 4. | Have a spiritual lifestyle (thanksgiving and praying always) (X1.1.4) | 0 | 3 | 48 | 214 | 255 | 2.281 | 4.39 |

| 5. | Maintaining the sacred or spiritual values of Bali (X1.1.5) | 0 | 0 | 48 | 208 | 266 | 2.298 | 4.42 |

| 6. | Applying Balinese spatial ethics (X1.1.6) | 0 | 4 | 30 | 207 | 279 | 2.321 | 4.46 |

| B. | Pawongan (X1.2) (Social) | 4.40 | ||||||

| 1. | The spirit of gotong royong (partnering and collaboration) (X1.2.1) | 0 | 3 | 31 | 206 | 280 | 2.323 | 4.47 |

| 2. | Appreciate art and culture (X1.2.2) | 0 | 4 | 43 | 231 | 242 | 2.271 | 4.37 |

| 3. | Maintain harmony in society (X1.2.3) | 0 | 6 | 37 | 224 | 253 | 2.284 | 4.39 |

| 4. | Carry out the teachings of Tat Twam Asi (I am you & you are me) (X1.2.4) | 0 | 7 | 26 | 228 | 259 | 2.299 | 4.42 |

| 5. | Maintaining harmony with local residents, immigrants, and tourists (X1.2.5) | 0 | 6 | 19 | 228 | 267 | 2.316 | 4.45 |

| 6. | Maintaining the local wisdom of the Balinese people (X1.2.6) | 0 | 5 | 42 | 250 | 223 | 2.251 | 4.33 |

| 7. | Synergize in building the existence of Bali tourism (X1.2.7) | 0 | 5 | 39 | 251 | 225 | 2.256 | 4.34 |

| 8. | Creative and innovative human resources in promoting Balinese culture (X1.2.8) | 0 | 3 | 33 | 232 | 252 | 2.293 | 4.41 |

| C. | Palemahan (X1.3) (Natural) | 4.34 | ||||||

| 1. | Strive to reduce, reuse, and recycle waste (X1.3.1) | 1 | 1 | 41 | 265 | 319 | 2.296 | 4.42 |

| 2. | Adequate waste/waste management (X1.3.2) | 0 | 3 | 42 | 273 | 309 | 2.278 | 4.38 |

| 3. | Preserve and protect flora, fauna, water, and energy sources (X1.3.3) | 2 | 16 | 95 | 266 | 248 | 2.225 | 4.28 |

| 4. | Wise land use (prioritizing local culture and open space) (X1.3.4) | 5 | 11 | 81 | 261 | 269 | 2.230 | 4.29 |

| 5. | Applying the concept of traditional Balinese architecture (X1.3.5) | 1 | 10 | 68 | 284 | 264 | 2.272 | 4.37 |

| 6. | Maintain harmony between worldly and non-worldly (X1.3.6) | 2 | 12 | 91 | 242 | 280 | 2.233 | 4.29 |

| 7. | Preserving the Tri Mandala in the environment (main area, transition area, & outer area) (X1.3.7) | 1 | 5 | 46 | 279 | 296 | 2.249 | 4.33 |

| 8. | Availaibity of a temporary dump (X1.3.8) | 2 | 6 | 79 | 257 | 283 | 2.275 | 4.38 |

| Overall Tri Hita Karana implementation score | 4.40 | |||||||

Appendix B.2.2. Destination Image Mean Scores

| No | Items | Respondent Ranking | Total Score | Mean Score | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||

| A. | Cognitive (Y1.1) | 4.39 | ||||||

| 1. | The people are friendly and helpful (Y1.1.1) | 0 | 1 | 42 | 231 | 246 | 2.282 | 4.39 |

| 2. | Standard hygiene and cleanliness conditions (Y1.1.2) | 0 | 4 | 38 | 258 | 220 | 2.254 | 4.33 |

| 3. | Values of money for holidays (Y1.1.3) | 0 | 1 | 44 | 242 | 233 | 2.267 | 4.36 |

| 4. | Destination has good infrastructure and fascinating architecture (Y1.1.4) | 0 | 2 | 30 | 222 | 266 | 2.312 | 4.45 |

| 5. | Excellent and suitable accommodation (Y1.1.5) | 0 | 2 | 33 | 236 | 249 | 2.292 | 4.41 |

| B. | Affective (Y1.2) | 4.49 | ||||||

| 1. | Pleasant and thrilling place (Y1.2.1) | 0 | 1 | 29 | 213 | 277 | 2.326 | 4.47 |

| 2. | Lively place (Y1.2.2) | 0 | 4 | 21 | 214 | 281 | 2.332 | 4.48 |

| 3. | Feel quite excited about this place (Y1.2.3) | 0 | 1 | 22 | 210 | 287 | 2.343 | 4.51 |

| C. | Unique (Y1.3) | 4.53 | ||||||

| 1. | Unique communities and historical sites (Y1.3.1) | 0 | 3 | 27 | 237 | 360 | 2.835 | 4.52 |

| 2. | Unique climate and natural beauty (Y1.3.2) | 0 | 4 | 30 | 231 | 362 | 2.832 | 4.52 |

| 3. | Unique cultural diversity (Y1.3.3) | 0 | 2 | 34 | 213 | 378 | 2.848 | 4.54 |

| Overall destination image score | 4.47 | |||||||

Appendix B.2.3. Destination Quality Mean Scores

| No | Items | Respondent Ranking | Total Score | Mean Score | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||

| A. | Infrastructure quality (X2.1) | 4.40 | ||||||

| 1. | Information center availability (X2.1.1) | 0 | 5 | 65 | 233 | 217 | 2.222 | 4.27 |

| 2. | Amenities availability (X2.1.2) | 0 | 1 | 27 | 247 | 245 | 2.296 | 4.42 |

| 3. | Pubs/entertainment availability (X2.1.3) | 0 | 2 | 28 | 218 | 272 | 2.230 | 4.46 |

| 4. | Easy to get daily needs (X2.1.4) | 0 | 2 | 52 | 228 | 238 | 2.262 | 4.35 |

| 5. | Easy to get foods and drinks (X2.1.5) | 0 | 3 | 23 | 213 | 281 | 2.332 | 4.48 |

| B. | Human resource quality (X2.2) | 4.46 | ||||||

| 1. | Have an adequate educational background (X2.2.1) | 0 | 2 | 33 | 212 | 273 | 2.316 | 4.45 |

| 2. | Have good hospitality (X2.2.2) | 0 | 2 | 30 | 214 | 274 | 2.320 | 4.46 |

| C. | Natural and environmental quality (X2.3) | 4.35 | ||||||

| 1. | Get real experience (X2.3.1) | 0 | 2 | 43 | 205 | 270 | 2.303 | 4.43 |

| 2. | Has a cultural tourist attraction (X2.3.2) | 0 | 2 | 42 | 206 | 270 | 2.304 | 4.43 |

| 3. | Reasonable price (X2.3.3) | 0 | 2 | 63 | 228 | 223 | 2.228 | 4.28 |

| 4. | Have good hygiene and sanitation (X2.3.4) | 0 | 5 | 52 | 240 | 253 | 2.241 | 4.31 |

| 5. | Has a low level of interference (X2.3.5) | 0 | 16 | 54 | 231 | 219 | 2.213 | 4.26 |

| 6. | Gaining experience is worth the sacrifices incurred (X2.3.6) | 0 | 3 | 47 | 233 | 237 | 2.264 | 4.35 |

| 7. | Good level of security (X2.3.7) | 0 | 3 | 44 | 240 | 233 | 2.263 | 4.35 |

| Overall destination quality score | 4.40 | |||||||

Appendix B.2.4. Revisit Intention Mean Scores

| No | Items | Respondent Ranking | Total Score | Mean Score | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||

| 1. | I will visit again (Y2.1) | 1 | 2 | 13 | 150 | 354 | 2.414 | 4.64 |

| 2. | I will recommend Bali to others (Y2.2) | 0 | 1 | 18 | 139 | 362 | 2.422 | 4.66 |

| 3. | I have plans to revisit Bali in the near future (Y2.3) | 1 | 14 | 33 | 149 | 233 | 2.339 | 4.50 |

| 4. | I consider Bali as my first choice (Y2.4) | 1 | 13 | 54 | 188 | 264 | 2.261 | 4.35 |

| 5. | Willingness to visit (Y2.5) | 1 | 1 | 22 | 198 | 298 | 2.351 | 4.52 |

| Overall revisit intention score | 4.53 | |||||||

Appendix B.3. Factor Loadings

| Constructs, Dimensions and Indicator Items | Load Factors |

| THK implementation | |

| Parhyangan (X1.1) | |

| Take good care of places of worship (X1.1.1) | 0.625 |

| Upholding the diversity of religions and beliefs (X1.1.2) | 0.627 |

| Faithfully attend spiritual meetings (X1.1.3) | 0.719 |

| Have a spiritual lifestyle (thanksgiving and praying always) (X1.1.4) | 0.681 |

| Maintaining the sacred or spiritual values of Bali (X1.1.5) | 0.654 |

| Applying Balinese spatial ethics (X1.1.6) | 0.653 |

| Pawongan (X1.2) | |

| The spirit of gotong royong (partnering and collaboration) (X1.2.1) | 0.660 |

| Appreciate art and culture (X1.2.2) | 0.679 |

| Maintain harmony in society (X1.2.3) | 0.774 |

| Carry out the teachings of Tat Twam Asi (I am you & you are me) (X1.2.4) | 0.823 |

| Maintaining harmony with local residents, immigrants, and tourists (X1.2.5) | 0.687 |

| Maintaining the local wisdom of the Balinese people (X1.2.6) | 0.674 |

| Synergize in building the existence of Bali tourism (X1.2.7) | 0.705 |

| Creative and innovative human resources in promoting Balinese culture (X1.2.8) | 0.632 |

| Palemahan (X1.3) | |

| Strive to reduce, reuse, and recycle waste (X1.3.1) | 0.769 |

| Adequate waste/waste management (X1.3.2) | 0.789 |

| Preserve and protect flora, fauna, water, and energy sources (X1.3.3) | 0.745 |

| Wise land use (prioritizing local culture and open space) (X1.3.4) | 0.694 |

| Applying the concept of traditional Balinese architecture (X1.3.5) | 0.754 |

| Maintain harmony between worldly and non-worldly (X1.3.6) | 0.616 |

| Preserving the Tri Mandala in the environment (main area, transition area, & outer area) (X1.3.7) | 0.805 |

| Avalaibity of a temporary dump (X1.3.8) | 0.769 |

| Destination quality | |

| Infrastructure quality (X2.1) | |

| Information center availability (X2.1.1) | 0.605 |

| Amenities availability (X2.1.2) | 0.702 |

| Pubs/entertainment availability (X2.1.3) | 0.699 |

| Easy to get daily needs (X2.1.4) | 0.565 |

| Easy to get foods and drinks (X2.1.5) | 0.798 |

| Human resource quality (X2.2) | |

| Have an adequate educational background (X2.2.1) | 0.664 |

| Have good hospitality (X2.2.2) | 0.833 |

| Natural and environmental quality (X2.3) | |

| Get real experience (X2.3.1) | 0.625 |

| Has a cultural tourist attraction (X2.3.2) | 0.742 |

| Reasonable price (X2.3.3) | 0.677 |

| Have good hygiene and sanitation (X2.3.4) | 0.796 |

| Has a low level of interference (X2.3.5) | 0.726 |

| Gaining experience is worth the sacrifices incurred (X2.3.6) | 0.823 |

| Good level of security (X2.3.7) | 0.622 |

| Destination image | |

| Cognitive (Y1.1) | |

| The people are friendly and helpful (Y1.1.1) | 0.756 |

| Standard hygiene and cleanliness conditions (Y1.1.2) | 0.740 |

| Values of money for holidays (Y1.1.3) | 0.804 |

| Destination has good infrastructure and fascinating architecture (Y1.1.4) | 0.669 |

| Excellent and suitable accommodation (Y1.1.5) | 0.809 |

| Affective (Y1.2) | |

| Pleasant and thrilling place (Y1.2.1) | 0.756 |

| Lively place (Y1.2.2) | 0.740 |

| Feel quite excited about this place (Y1.2.3) | 0.804 |

| Unique (Y1.3) | |

| Unique communities and historical sites (Y1.3.1) | 0.683 |

| Unique climate and natural beauty (Y1.3.2) | 0.675 |

| Unique cultural diversity (Y1.3.3) | 0.629 |

| Revisit intention | |

| I will visit again (Y2.1) | 0.747 |

| I will recommend Bali to others (Y2.2) | 0.760 |

| I have plans to revisit Bali in the near future (Y2.3) | 0.751 |

| I consider Bali as my first choice (Y2.4) | 0.671 |

| Willingness to visit (Y2.5) | 0.760 |

Appendix B.4. Discriminant Validity Tests

| Constructs | THK (X1) | Destination Quality (X2) | Destination Image (Y1) | Revisit Intention (Y2) |

| THK implementation (X1) | 0.708 | |||

| Destination quality (X2) | 0.508 | 0.710 | ||

| Destination image (Y1) | 0.550 | 0.588 | 0.710 | |

| Revisit intention (Y2) | 0.365 | 0.372 | 0.419 | 0.739 |

| Indicator Items | THK (X1) | Destination Quality (X2) | Destination Image (Y1) | Revisit Intention (Y2) |

| X1.1.1 | 0.625 | 0.383 | 0.349 | 0.285 |

| X1.1.2 | 0.627 | 0.387 | 0.354 | 0.355 |

| X1.1.3 | 0.719 | 0.318 | 0.407 | 0.245 |

| X1.1.4 | 0.681 | 0.405 | 0.386 | 0.318 |

| X1.1.6 | 0.653 | 0.356 | 0.395 | 0.322 |

| X1.2.1 | 0.660 | 0.353 | 0.385 | 0.336 |

| X1.2.2 | 0.679 | 0.431 | 0.412 | 0.268 |

| X1.2.3 | 0.774 | 0.323 | 0.413 | 0.268 |

| X1.2.4 | 0.823 | 0.348 | 0.417 | 0.271 |

| X1.2.5 | 0.687 | 0.338 | 0.429 | 0.233 |

| X1.2.6 | 0.674 | 0.385 | 0.394 | 0.230 |

| X1.2.7 | 0.705 | 0.385 | 0.419 | 0.256 |

| X1.2.8 | 0.632 | 0.369 | 0.423 | 0.249 |

| X1.3.1 | 0.769 | 0.406 | 0.445 | 0.266 |

| X1.3.2 | 0.789 | 0.382 | 0.399 | 0.244 |

| X1.3.3 | 0.745 | 0.302 | 0.318 | 0.202 |

| X1.3.4 | 0.694 | 0.280 | 0.287 | 0.151 |

| X1.3.4 | 0.694 | 0.280 | 0.287 | 0.151 |

| X1.3.5 | 0.754 | 0.319 | 0.375 | 0.218 |

| X1.3.6 | 0.751 | 0.338 | 0.378 | 0.210 |

| X1.3.7 | 0.616 | 0.357 | 0.409 | 0.241 |

| X1.3.8 | 0.805 | 0.371 | 0.416 | 0.244 |

| X2.1.1 | 0.341 | 0.605 | 0.350 | 0.276 |

| X2.1.2 | 0.390 | 0.702 | 0.488 | 0.245 |

| X2.1.3 | 0.367 | 0.699 | 0.507 | 0.302 |

| X2.1.4 | 0.379 | 0.565 | 0.428 | 0.216 |

| X2.1.5 | 0.395 | 0.798 | 0.495 | 0.290 |

| X2.2.1 | 0.334 | 0.664 | 0.404 | 0.238 |

| X2.2.2 | 0.381 | 0.833 | 0.469 | 0.286 |

| X2.3.1 | 0.359 | 0.625 | 0.332 | 0.391 |

| X2.3.3 | 0.322 | 0.677 | 0.320 | 0.346 |

| X2.3.4 | 0.415 | 0.796 | 0.404 | 0.219 |

| X2.3.5 | 0.420 | 0.726 | 0.373 | 0.212 |

| X2.3.6 | 0.341 | 0.823 | 0.407 | 0.202 |

| X2.3.7 | 0.293 | 0.622 | 0.411 | 0.220 |

| Y1.1.1 | 0.394 | 0.438 | 0.756 | 0.317 |

| Y1.1.2 | 0.425 | 0.420 | 0.740 | 0.266 |

| Y1.1.3 | 0.391 | 0.465 | 0.804 | 0.306 |

| Y1.1.4 | 0.352 | 0.429 | 0.669 | 0.217 |

| Y1.1.5 | 0.346 | 0.441 | 0.809 | 0.257 |

| Y1.2.1 | 0.427 | 0.427 | 0.692 | 0.335 |

| Y1.2.2 | 0.413 | 0.389 | 0.634 | 0.350 |

| Y1.2.3 | 0.429 | 0.447 | 0.688 | 0.357 |

| Y1.3.1 | 0.376 | 0.396 | 0.683 | 0.270 |

| Y1.3.2 | 0.421 | 0.369 | 0.675 | 0.266 |

| Y1.3.3 | 0.307 | 0.355 | 0.629 | 0.315 |

| Y2.1 | 0.234 | 0.232 | 0.329 | 0.747 |

| Y2.2 | 0.330 | 0.288 | 0.386 | 0.760 |

| Y2.3 | 0.251 | 0.260 | 0.290 | 0.751 |

| Y2.4 | 0.258 | 0.285 | 0.199 | 0.671 |

| Y2.5 | 0.263 | 0.311 | 0.313 | 0.760 |

Appendix B.5. Multicollinearity Statistics (VIF)

| Constructs | Inner VIF Value |

| THK implementation → Revisit intention | 1.150 |

| Destination quality → Revisit intention | 1.653 |

| Destination image → Revisit intention | 1.757 |

| THK implementation → Destination image | 1.349 |

| Destination quality → Destination image | 1.349 |

Appendix B.6. Effect Size (f-Square, f2)

| Constructs and Dimensions | f2 |

| THK implementation → Revisit intention | 0.154 |

| Destination quality → Revisit intention | 0.150 |

| Destination image → Revisit intention | 0.246 |

| Parhyangan → THK implementation | 0.855 |

| Pawongan → THK implementation | 0.932 |

| Palemahan → THK implementation | 0.913 |

| Infrastructure quality → Destination quality | 0.898 |

| Human resource quality → Destination quality | 0.805 |

| Natural and environmental quality → Destination quality | 0.927 |

| Cognitive → Destination image | 0.879 |

| Affective → Destination image | 0.802 |

| Unique → Destination image | 0.797 |

| THK implementation → Destination image | 0.338 |

| Destination quality → Destination image | 0.416 |

References

- Picard, M. Cultural tourism nation-building regional culture: The making of a Balinese identity. In Tourism, Ethnicity, and the State in Asian and Pacific Societies; Picard, M., Wood, R., Eds.; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G.; Russo, A.P. Alternative and Creative Tourism; Association for Tourism and Leisure Education: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Babolian, H.R. Delivering tourism intelligence about agritourism, delivering tourism intelligence. Bridg. Tour. Theory Pract. 2019, 11, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, D.; Sedana, G. Reframing Tri Hita Karana: From ‘Balinese culture’ to politics. Asia Pac. J. Anthropol. 2015, 16, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, M.; Flora, C. Spiraling-up: Mapping community transformation with community capitals framework. Community Dev. 2006, 37, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Cultural Landscape of Bali Province: The Subak System as a Manifestation of the Tri Hita Karana Philosophy. 2023. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1194/ (accessed on 31 August 2024).

- Bali Regional Regulation No. 5 of 2020. Available online: https://ijcjs.com/menu-script/index.php/ijcjs/article/download/492/367?__cf_chl_tk=hR5OHBz5gFGzamQLcpUvm1vQVZpRTuYRibMQkRbiAow-1730361979-1.0.1.1-9qwaXnTItRQLXD2XGoGwrl1D6WmBEpubmzXIQ2kNpY8 (accessed on 31 August 2024).

- Mohaidin, Z.; Wei, K.T.; Ali Murshid, M. Factors influencing the tourists’ intention to select sustainable tourism destination: A case study of Penang, Malaysia. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2017, 3, 442–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahijan, M.K.; Rezaei, S.; Amin, M. Qualities of effective cruise marketing strategy: Cruisers’ experience, service convenience, values, satisfaction and revisit intention. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2018, 36, 2304–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Nayak, J.K. Do tourists’ emotional experiences influence images and intentions in yoga tourism? Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 646–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawati, A.; Utomo, H.S.; Suharyono, S.; Sunarti, S. Effects of sustainability on WOM intention and revisit intention, with environmental awareness as a moderator. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2020, 31, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.; Marzuki, A.; Kiumarsi, S. Perceived conference quality, quality services and experiences in hospitality and tourism. Bridg. Tour. Theory Pract. 2018, 9, 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Canalejo, A.M.C.; del Rio, J.A.J. Quality, satisfaction and loyalty indices. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2018, 11, 428–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saragih, H.S.; Jonathan, P. Views of Indonesian consumers towards medical tourism experience in Malaysia. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2019, 13, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiby, M.A.; Slåtten, T. The role of aesthetic experiential qualities for tourist satisfaction and loyalty. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbekova, A.; Uysal, M.; Assaf, A.G. Toward an assessment of quality of life indicators as measures of destination performance. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 1424–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.M. Marketing and Managing Tourism Destinations, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, G.; Mathieson, A. Tourism Changes, Impacts and Opportunities; Pearson Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Then, J.; Yulius, K.G. Motivation and interest in traveling of young traveler during revenge tourism. Glob. Res. Tour. Dev. Adv. 2022, 4, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogler, R. Revenge and catch-up travel or degrowth? Debating tourism post COVID-19. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 93, 103272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Clark, D.N. Resource-Based Theory Creating and Sustaining Competitive Advantage; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rothaermel, F.T. Strategic Management; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, S.A. The resource-based view, resourcefulness, and resource management in startup firms: A proposed research agenda. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 1841–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D. Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Rimmington, M. Tourist satisfaction with Mallorca, Spain, as an off-season holiday destination. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claver-Cortes, E.; Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Pereira-Moliner, J. The impact of strategic behaviors on hotel performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Moliner, J.; Font, X.; Tarí, J.J.; Molina-Azorin, J.F.; Lopez-Gamero, M.D.; Pertusa-Ortega, E.M. The holy grail: Environmental management, competitive advantage and business performance in the Spanish hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 714–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séraphin, H.; Gowreesunkar, V.G.B. Conclusion: What marketing strategy for destinations with a negative image? Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2017, 9, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, E.; Hwang, Y.K.; Kim, E.Y. Green marketing’s functions in building corporate image in the retail setting. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1709–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, G.P.; Melé, P.M.; García, F.A. Corporate image and destination image: The moderating effect of the motivations on the destination image of Spain in South Korea. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, J.; Shabbirhusain, R.V. Role of self-congruity in predicting travel intention. In Methodological Issues in Management Research: Advances, Challenges, and the Way Ahead; Subudhi, R.N., Mishra, S., Eds.; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2019; pp. 261–267. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Lu, L.; Xu, L.; Wu, B.; Wu, Y. Alike but different: Four ancient capitals in China and their destination images. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2020, 6, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, D.; Han, H. Personality, social comparison, consumption emotions, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 970–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allameh, S.M.; Pool, J.K.; Jaberi, A.; Salehzadeh, R.; Asadi, H. Factors influencing sport tourists’ revisit intentions: The role and effect of destination image, perceived quality, perceived value and satisfaction. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2015, 27, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J.; Garau, J. Tourist satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akroush, M.N.; Jraisat, L.E.; Kurdieh, D.J.; AL-Faouri, R.N.; Qatu, L.T. Tourism service quality and destination loyalty. The mediating role of destination image from international tourists’ perspectives. Tour. Rev. 2016, 71, 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.L.; Tran, P.T.K.; Tran, V.T. Destination perceived quality, tourist satisfaction and word-of-mouth. Tour. Rev. 2017, 72, 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, D. Extending the theory of planned behavior to understand consumers’ intentions to visit green hotels in the Chinese context. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2810–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Jeong, E. The effect of message framings and green practices on customers’ attitudes and behavior intentions toward green restaurants. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2270–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phau, I.; Shanka, T.; Dhayan, N. Destination image and choice intention of university student travelers To Mauritius. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 22, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapito, D.; Oom do Valle, P.; da Costa Mendes, J. The cognitive-affective-conative model of destination image: Confirmatory Analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, N.; James, R.; Michael, I. Australia’s cognitive, affective and conative destination image: An Emirati tourist perspective. J. Islam. Mark. 2018, 9, 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-B.; Lee, S. Impacts of city personality and image on revisit intention. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2015, 1, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lehto, X.; Kandampully, J. The role of familiarity in consumer destination image formation. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 885–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Rosa, S.; dos Anjos, F.A.; Pereira, M.d.L.; Arnhold Junior, M. Image perception of surf tourism destination in Brazil. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2020, 6, 1111–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawadieh, Z.; Dincer, M.Z.; Istanbullu Dincer, F.; Mammadova, P. Understanding destination image from the perspective of Western travel bloggers: The case of Istanbul. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 12, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, H.; Mahrous, A.A.; Ghoneim, A. Egypt’s perceived destination image and its impact on tourist’s future behavioral intentions. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2020, 6, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Tourism of the Republic of Indonesia. Material for the National Tourism Working Meeting. In Digitization of Destinations and Nomadic Tourism; BNDCC Nusa Dua Bali: Kuta Selatan, Indonesia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zerva, K.; Huete, R.; Segovia-Pérez, M. Digital nomad tourism: The experience of living at the destination. In Remodelling Businesses for Sustainable Development; Negrușa, A.L., Coroş, M.M., Eds.; ICMTBHT 2022. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 15–26. Available online: https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.purdue.edu/10.1007/978-3-031-19656-0_2 (accessed on 31 August 2024).

- Makimoto, T. The age of the digital nomad: Impact of CMOS innovation. IEEE Solid-State Circuits 2013, 5, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Nomadic Tourism for Mongolia. Critical Issues in Silk Road Tourism. 2016. Available online: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/imported_images/45889/3._gansukh_damba.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2024).

- Mahadewi, N.M.E. Nomadic tourism, educational tourism, digitization and event tourism in the development of homestay accommodation services businesses in tourist destinations. J. Tour. 2018, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mulyana, C.; Sudana, I.P.; Sagita, P.A.W. Digital nomads’ perceptions and motivations for traveling in Tibubeneng Village, Canggu, North Kuta. Travel Ind. J. 2020, 8, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Chevtaeva, E.; Denizci-Guillet, B. Digital nomads’ lifestyles and coworkation. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 21, 100633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cheng, Z.; Kim, G.-B. Make it memorable: Tourism experience, fun, recommendation and revisit intentions of Chinese outbound tourists. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.L.J. The supply-side definition of tourism reply to Leiper. Ann. Tour. Res. 1991, 18, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, B.F. Price value perceptions of travelers. J. Travel Res. 1992, 31, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.; Pritchard, M.P.; Smith, B. The destination product and its impact on traveler perceptions. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limberger, P.F.; dos Anjos, F.A.; Meira, J.V.S.; dos Anjos, S.J.G. Satisfaction in hospitality on Tripadvisor.com: An analysis of the correlation between evaluation criteria and overall satisfaction. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2014, 10, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- dos Anjos, S.J.G.; Meira, J.V.d.S.; Pereira, M.d.L.; Limberger, P.F. Quality attributes of Jericoacoara, Brazil. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2017, 3, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, C.A. Vacationscape: Designing Tourist Regions; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, J.L. Motivations for pleasure vacation. J. Travel Res. 1979, 6, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Can. Geogr. 2008, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.C. Image formation process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1993, 2, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echtner, C.M.; Ritchie, J.R.B. The meaning and measurement of destination image. J. Tour. Stud. 2003, 14, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, S. Destination brand positions of a competitive set of near-home destinations. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konecnik, M.; Gartner, W.C. Customer-based brand equity for a destination. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 400–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukawati, T.G.A.I.; Sukaatmadja, I.P.G.; Yasa, N.N.K.; Widagda, I.G.N.J.A. The role of local wisdom culture moderating the effect of product differentiation, service differentiation, and image differentiation on tourist satisfaction (Case study of tourist satisfaction at Royal Kirana Spa & Wellness Ubud). Int. Res. J. Manag. IT Soc. Sci. 2021, 8, 377–392. [Google Scholar]

- Yeap, J.A.L.; Ong, K.S.G.; Yapp, E.H.T.; Ooi, S.K. Hungry for more: Understanding young domestic travelers’ return for Penang street food. Br. Food J. 2019, 122, 1935–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandasena, R.; Morrison, A.M.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. Transformational tourism—A systematic literature review and research agenda. J. Tour. Futures 2022, 8, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Weiler, B. What’s special about special interest tourism? In Special Interest Tourism; Weiler, B., Hall, C.M., Eds.; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1992; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, C.-K.; Yoon, D.; Park, E. Tourist motivation: An integral approach to destination choices. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Dokania, A.K.; Pathak, G.S. The influence of green marketing functions in building corporate image. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2178–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Belhassen, Y.; Shani, A. Destination image, on-site experience and behavioral intentions: Path analytic validation of a marketing model on domestic tourists. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1653–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.C.; Moretti, A. Antecedents and moderators of golf tourists’ behavioral intentions: An empirical study in a Mediterranean destination. EuroMed J. Bus. 2015, 10, 338–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaratnam, S.D.; Nair, V.; Sharif, S.P.; Munikrishnan, U.T. Destination quality and tourists’ behavioral intentions: Rural tourist destinations in Malaysia. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2015, 7, 463–472. [Google Scholar]

- Fam, K.-S.; Ting, H.; Tan, K.-L.; Hussain, K.; Cheah, J.-H. Does it matter where to run? Intention to participate in destination marathon. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 1475–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kwifi, O.S. The impact of destination images on tourists’ decision making: A technological exploratory study using fMRI. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2015, 6, 174–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, A.M.W.; Yeh, S.-S.; Chang, L.-H. Nostalgic tourism in Macau: The bidirectional causal relationship between destination image and experiential value. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2015, 6, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Evren, S.; Evren, S.E.; Çakıcı, A.C. Moderating effect of optimum stimulation level on the relationship between satisfaction and revisit intention: The case of Turkish cultural tourists. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, E.; Del Chiappa, G.; Coudounaris, D.N.; Björk, P. Tourism experiences, memorability and behavioral intentions: A study of tourists in Sardinia, Italy. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 533–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpenny, E.; Kono, S.; Moghimehfar, F. Predicting World Heritage Site visitation intentions of North American park visitors. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2018, 9, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Villar, F.R. Destination image restoration through local gastronomy: The rise of Baja Med cuisine in Tijuana. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 14, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guachalla, A. Cultural capital and destination image: Insights from The Opera House tourist. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2021, 7, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perovic, Ð.; Moric, I.; Pekovic, S.; Stanovcic, T.; Roblek, V.; Bach, M.P. The antecedents of tourist repeat visit intention: Systemic approach. Kybernetes 2018, 47, 1857–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordanova, E.; Stylidis, D. The impact of visitors’ experience intensity on in-situ destination image formation. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 841–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzschentke, N.; Kirk, D.; Lynch, P.A. Reasons for going green in serviced accommodation establishments. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2004, 16, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukawati, T. Establishing local wisdom values to develop sustainable competitiveness excellence. J. Manag. Mark. Rev. 2017, 2, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, N. Development of local wisdom-based tourism. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Humanit. Res. 2018, 282, 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Yasa, N.; Giantari, I.G.A.K.; Setini, M.; Sarmawa, W.; Rahmayanti, P.; Dharmanegara, I. Service strategy based on Tri Kaya Parisudha, social media promotion, business values and business performance. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 2961–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasa, N.N.K.; Adnyani, I.G.A.D.; Rahmayanti, P.L.D.; Dharmanegara, I.B.A. Integration of partnership strategy models based on local values of “Tat Twam Asi” with competitive advantages and business performance: A conceptual model. IAR J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 1, 402–405. [Google Scholar]

- Grybovych, O. Designing a qualitative multi-case research study to examine participatory community tourism planning practices. In Field Guide to Case Study Research in Tourism, Hospitality and Leisure Advances in Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research; Hyde, K.F., Ryan, C., Woodside, A.G., Eds.; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2012; Volume 6, pp. 501–520. [Google Scholar]

- Peric, M.; Djurkin, J. Systems thinking and alternative business model for responsible tourist destination. Kybernetes 2014, 43, 480–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekaota, L. The importance of rural communities’ participation in the management of tourism management. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2015, 7, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.A.; Croes, R.; Villanueva, J.B. Rise and fall of community-based tourism—Facilitators, inhibitors and outcomes. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2014, 6, 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Gudlaugsson, T.; Magnússon, G. North Atlantic island destinations in tourists’ minds. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2012, 6, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.A.; Darzi, M.A. Antecedents of tourist loyalty to tourist destinations: A mediated-moderation study. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2018, 4, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, X.Y.; Jiang, L. How do Destination Facebook pages work? An extended TPB model of fans’ visit intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2018, 9, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drumwright, M.E. Socially responsible organizational buying: Environmental concern as a noneconomic buying criterion. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, Y. An investigation of green hotel customers’ decision formation: Developing an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.J.; Sheu, C. Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Hsu, L.T.; Han, H.; Kim, Y. Understanding how consumers view green hotels: How a hotel’s green image can influence behavioral intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylos, N.; Vassiliadis, C.A.; Bellou, V.; Andronikidis, A. Destination images, holistic images and personal normative beliefs: Predictors of intention to revisit a destination. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Cherifi, B. Characteristics of destination image: Visitors and non-visitors’ images of London. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Kirilenko, A.P.; Shichkova, E. Influential factors for intention to visit an adversarial nation: Increasing robustness and validity of findings. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 491–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plog, S.C. Why destination areas rise and fall in popularity. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 1974, 14, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, R.W. Situational variables and consumer behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1975, 2, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeldner, C.R.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Tourism Principles, Practices, and Philosophies; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, A.K.; Brown, G. Understanding the relationships between perceived travel experiences, overall satisfaction, and destination loyalty. Anatolia Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2012, 23, 328–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Han, H. Destination attributes influencing Chinese travelers’ perceptions of experience quality and intentions for island tourism: A case of Jeju Island. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.; Hamilton, K. Recapturing place identification through community heritage marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 1118–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Liu, C.-H.S. Moderating and mediating roles of environmental concern and ecotourism experience for revisit intention. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1854–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, H. The impact of cultural values and economic constraints on tourism businesses’ ethical practices. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2018, 5, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madiun, I.N. Nusa Dua Modern Tourism Area Development Model; Udayana University Press: Denpasar, Indonesia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, C.-H.; Lo, M.-C.; Songan, P.; Nair, V. Rural tourism destination competitiveness: A study on Annah Rais Longhouse Homestay, Sarawak. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 144, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.H.; Wardana, W. Tri Hita Karana the Spirit of Bali; Gramedia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Templeton, G.F.; Lewis, B.R.; Snyder, C.A. Development of a measure for the organizational learning construct. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2002, 19, 175–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]