Abstract

This research explores the concept of placemaking in the context of sports events tourism, using the case study of the 2019 Rugby World Cup hosted in Japan. The study investigates how host cities used liminoid spaces between transport hubs and stadiums to create a festive atmosphere and articulate the identity of the place itself. Employing a novel ethnographic methodology centred around walking and participatory methods, the researcher occupied a dual tourist-researcher role, immersing himself in the liminoid space. Findings suggest that the use of such spaces was innovative and successful in creating a sense of place and developing a festive atmosphere through which visitors moved. However, the study acknowledges that these strategies may not be applicable to all sports events and that the direct experiences of visitors through ethnographic methods do not allow for empirical claims about the success of strategies or their longitudinal effects. Nevertheless, the study highlights the potential of placemaking in the periphery of sports events to enhance the visitor experience and promote the identity of the host destination.

1. Introduction

In 2019, 242,000 rugby fans travelled to Japan for the 2019 Rugby World Cup (RWC) [1], the first time it had been held in an Asian country since the tournament began in 1987 [2]. The third biggest international sports event after the Olympics and FIFA World Cup [3], 93 national teams attempted to qualify for the tournament, with 20 spots available. However, unlike the Olympics, the RWC was not centred on a single city, much less a capital city (although some matches did take place in Tokyo and neighbouring Saitama and Kanagawa prefectures). Indeed, the tournament was held in 12 host cities across the country from Fukuoka in the south to Sapporo in the north [4].

Sports tourism has been positioned by the Japanese government’s Japan Sports Agency as a means through which to revitalise regions [5]. As a country with a rapidly ageing population and a shrinking economy [6], tourism has been adopted as a key strategy for economic growth [7]. While Tokyo has traditionally been the main destination for inbound tourists [8], the 2019 RWC created conditions for visitors to experience a more diverse set of destinations and enable those destinations to develop their tourism industries. However, despite the tournament being positioned as a “Once in a Lifetime” event [9], at the time of writing, comparatively little academic research has been published on the event, in either English or Japanese.

As the world recovers from the pandemic, there is increasing recognition and demand for sustainability to be at the centre of the tourism and events industries’ revitalisation [10]. To avoid the phenomenon of overtourism, tourism cannot be concentrated around a single location. Multi-city events like the RWC, on the other hand, offer the opportunity for the event and its benefits to be distributed across a country. Mensah and Boakye argue that post-COVID, a rethinking of tourism and “re-staging” of events can and should lead to a diversification of tourism offerings [11]. Sports events have the potential to transform destinations through tourism, especially when utilised strategically [12].

When a major international sports event is held in a location that is not widely known abroad, there is an opportunity for utilising the event to increase the recognition of that location and develop its destination brand. However, if placemaking or destination branding activities are to occur, there is an important question: “where should it take place?” Event organisers may strictly control the branding at the host venue, allowing only event branding and disallowing destination-specific branding. Depending on the event, visitors may head straight for the venue, such as a stadium, often on the edge of a town or city. This presents a challenge for a host destination wishing to develop tourism because visitors need to be exposed to the placemaking efforts in order to encourage tourism activities as well as create a positive experience of the destination that leads to Word of Mouth promotion and future tourism outcomes. If, upon arrival at the host destination’s main transit hub, the visitor travels straight to the venue, their time within the destination is significantly limited.

The location of an event and the event’s boundaries are thus very important considerations in the leveraging of an event for destination branding. In the case of some events, the whole city can be the venue, with activities taking place across the city. In such instances, developing and promoting a sense of place and brand for both locals and visitors poses fewer issues as visitors can be directed to attractions and local businesses can benefit from the increased footfall. However, a stadium is often outside of the city centre. Consequently, in the case of sports events, there is both a spatial and temporal distance between the arrival point of a visitor (e.g., a train or bus station) and the event venue. Visitors must necessarily travel between these points in order to reach the event, but where does the experience start?

While the official experience-scape of the event is within the venue grounds, a visitor’s experience is the sum of all parts, including travel. As temporary visitors to the place, they already employ the “tourist gaze” [13] on arrival in the destination. There is no sudden switch from a normal everyday mentality and experience to an event experience, but rather a gradual build-up of anticipation. When the venue comes into view, this may elicit excitement and trigger associations with the event atmosphere that awaits. In reality, this space between the arrival point and the event space is a liminoid one. It is a threshold, neither part of the event nor completely separate from it.

This research forms part of a larger project examining inbound tourism during the 2019 RWC. The project considers how, as a multi-city event, the 2019 RWC was leveraged for tourism development and how the tournament itself directly influenced tourist travel behaviour and experiences. The project is split into three main objectives:

- To understand the direct impacts of the 2019 RWC on tourism in host cities and its legacy impacts on tourism development;

- To understand how host cities leveraged the 2019 RWC to develop their sense of place as part of the visitor experience;

- To understand how the 2019 RWC directly impacted tourists’ travel behaviours and experiences of Japan [14].

This present paper relates to the second objective and is guided by the question:

How was the physical route between the arrival point and the event space used to create a sense of place for visitors?

In this article, I will use the case study of the 2019 RWC in Japan to demonstrate how such liminoid spaces were used by host cities to extend the experience-scape and cultivate a sense of place that complemented the main event brand while still presenting a unique destination experience for the visitor. Through an ethnographic investigation of the routes between stations and stadia in five host cities using a walking methodology, this case study suggests that local placemaking can exist alongside primary event branding. Rather than being a limited space in which to articulate the sense of place, as a space of transition into the experience-scape, these placemaking activities can directly contribute to visitor experience, as well as serve as conduit for visitors to create their own experiences.

2. Literature Review

Hosting a major international sports event is appealing to countries for the perceived benefits that it brings. In their analysis of the impacts of mega-sports events on tourist arrivals, analysing data from mega events between 1995 and 2006, Fourie and Santana-Gallego found that hosting a mega sports event would increase tourist numbers by 8% [15]. Hosting these kinds of events also necessitates investment in infrastructure, such as roads and public transport [16], benefitting both tourists and resident communities. The value of events is well researched, addressing the numerous benefits and impacts of events from economic, social, and political perspectives. As Carlsen, Robertson, and Ali-Knight note, historically, the emphasis of event value has been on economic impacts, but in recent years, greater attention has been paid to an increasing diversity of dimensions [17]. Similarly, in 2006, Chalip wrote of sports events’ untapped potential to be leveraged for social value in particular, especially around the notion of communitas, which is fostered in the event environment [18].

In the early 2000s, there was a stream of scholarly output relating to the role that sports events (and events more generally) can play in the construction of destination image (see, e.g., [19,20,21,22]). As Duignan and McGillivray observe, mega sports events “enable the local entrepreneurial state to engineer an urban facelift, prioritising developments that spearhead highly aestheticized images and narratives (by and large) for external consumption” [23], p. 278. Rather than image, Chalip and Costa refer to the destination “brand”, writing that the brand is “the overall impression that the destination creates in the minds of potential tourists, including its functional and symbolic elements” [20], p. 219. More than an image, a brand encapsulates a range of associations for a prospective tourist. More recently, Richards has suggested that the focus should be on an overall holistic approach of “placemaking” that not only improves the image and range of associations with the destination’s “brand”, but also improves the place for the host communities through regeneration and active engagement [24]. For placemaking to be successful, he argues that the events “need to add to the meaning of the location” [24], p. 7.

Before proceeding further, it is necessary to briefly establish what is meant by placemaking. In a review of literature pertaining to the subject, Lew found that there is a distinction between “place making”, which is seen as an organic imprinting of a culture on a place that is built up over time and imbues it with meaning, and “placemaking”, which is a top-down concerted activity to influence perceptions of a place, often aligned to tourism [25]. Here, we will consider placemaking from this latter perspective as the deliberate cultivation of a “sense of place”, although this necessarily includes the promotion of local culture, tradition, and heritage assets. Events have been seen as “catalysts” for placemaking, leading to a coordinated and strategic approach to the improvement and promotion of the destination [26].

It is important to recognise that well-established sports events may already have a defined brand image among its audience base as well as a more general brand image for those aware of the event. Where there is an established brand, when hosting the event these associations will be transferred to the destination; if the event is continuously held in the same destination, the “co-branding” between destination and event will be permanent, including both positive and negative connotations [20]. The physical space the event occupies and in which the experience plays out, otherwise known as the experience-scape, is vital to the spectator’s enjoyment of the experience [27]. Research has shown that a positive experience at an event has a positive correlation with the intention to participate in the event again [28]. However, this brings us back to the issue presented earlier: an established event will have established branding and visitors will have expectations about the experience. It may, therefore, be difficult for individual host cities to engage in placemaking activities at the event itself. They may need to conduct these on the event’s periphery.

While liminality has been used in events management/studies research, the complexity of the concept has meant that it has been understood and applied differently by different scholars [29]. There is insufficient space here to discuss liminality in detail, though readers may wish to look at Lamond and Moss’ 2020 edited volume Liminality and Critical Event Studies: Borders, Boundaries, and Contestation [30]. On the significance of liminality in sports events specifically, Chalip considers the liminal and liminoid in their anthropological senses, an “alteration of human affect” [17], p. 110, wherein participants experience an elevated sense of togetherness and an indescribable emotional connection. This same understanding of liminality is employed by Wu et al. in their study of Chinese music festivals, wherein the whole festival space is considered a liminal one since for the visitor the experience is an escape from the normal, everyday [31].

In this paper, I do not use a purely anthropological definition of liminality, but instead employ a more literal understanding of the liminoid space. To avoid this confusion, terms such as “threshold spaces” or “peripheral spaces” (indeed, “periphery” is in the article title itself) could alternatively be employed here, but doing so would lose important subtleties around the conceptualisation of space. However, these anthropological insights into the effect that such spaces have on participants are nonetheless useful in understanding these threshold spaces and align with other theories of tourist psychology such as Urry’s “tourist gaze” [13]. Falassi’s conceptualisation of the festival, which parallels religious ritual practices is also useful here. A key element of the festival identified by Falassi is “festive behavior”: that “people do something they normally do not; they abstain from something they normally do; they carry to the extreme behaviors that are usually regulated by measure; they invest patterns of daily social life” [32], p. 3. This broadly overlaps with conceptualisations of tourism, specifically Urry’s description of the characteristics of tourism, which he describes as a movement of people through space to a temporary location for purposes that are unconnected and contrast with work, ultimately a separation from the everyday [33], pp. 2–3. While distinct concepts, their relationship should not be understated as festivals serve as a motivator for individuals to visit a destination for tourism. Falassi also identifies parallels between sports events and “ritual games of the festival” [32], p. 6. While not explicitly compared, Falassi’s descriptions of festival structure and constituent rituals have clear analogies in the sports mega event. Taking the RWC as an example, as much as “Festival time imposes itself as an autonomous duration, not so much to be perceived and measured in days or hours, but to be divided internally by what happens within it from its beginning to its end” [32], p. 4, the tournament is defined less by its actual duration, and more by the matches that are played.

This paper also draws on Duignan, Down, and O’Brien’s use of the concept of liminality in their study of Olympic Transit Zones [34]. Here, they too focus on the physical liminoid space, the “Olympic Transit Zone”, a term they use to refer to the final part of a visitor’s journey from the transport hub to the venue. This final stretch between the transit hub and the venue is sometimes referred to as the “Last Mile”, an aspect of events that has received comparatively little attention [23].

3. Materials and Methods

This case study will specifically focus on the construction of spectator experience and host city placemaking within the liminoidal space at the 2019 RWC in Japan. Sports mega events like the RWC are social events and ethnography was, therefore, the most appropriate approach in order to examine the social experiences of the RWC. Indeed, Holloway, Brown, and Shipway have argued this point convincingly, noting a prevalence of quantitative data-driven studies which fail to develop understandings of participant experience [35].

Data collection comprised a limited naturalistic ethnographic study of the tournament in five host cities on match days: Yokohama, Osaka, Kobe, Fukuoka, and Kumagaya. These cities were selected to give a broad representation of tournament hosts. Yokohama and Osaka are Japan’s second and third most populous cities, Kobe and Fukuoka are port cities, and Kumagaya is a little-visited city an hour outside of Tokyo.

This naturalistic ethnographic enquiry was carried out through walking methodologies. Duignan and McGillivray argue that novel methodological approaches, specifically those “involved methodological techniques” [23], p. 280, like walking, can help better understand spatial arrangements at mega sports events. Walking is one of a range of mobile methods that recognise and attempt to understand the ways in which people and place combine, and how walking “within particular environments allows for the creation of meaning” [36], p. 1. Such methods are being developed out of a need to reinvigorate the social sciences, whose dated methodologies fit poorly with transient phenomena [37]. Moles suggests that walking as a methodology is suitable for investigating the “Third--space”, an in-between place that conflates both the physical place (otherwise known as “first-place”) and the conceptualisation and meaning of the place (or “second-place”) [36], pp. 2–3. Events spaces have a defined physicality, but their meaning is defined through the lived experience of the participant. The third-space provides a platform for investigating this interaction between physicality and interpretation, where the dynamic relationship between the participant and the space is explored in detail. Thus, mobile methods, such as walking, provide a useful means for comprehending the participant’s lived experience within event spaces and can offer insights that may not be captured through traditional methodologies.

Reviewing different approaches to walking as method, Springgay and Truman identified four common recurring concepts: “place, sensory inquiry, embodiment, and rhythm” (emphasis in original) [38], p. 2. Walking methodologies are significant as they provide a qualitative framework for investigating the construction of place and the interactions that occur within spaces. Walking, they write, “is a way of becoming responsive to place; it activates modes of participation that are situated and relational” [38], p. 4. To understand how place is constructed at an event, participation, on the ground, moving through the space, reveals experiences and enables observations that could not be made from the outside. In carrying out ethnography by walking, researchers must draw on their senses to observe the sights, sounds, and smells of the phenomenon.

This particular research draws inspiration from Duignan and McGillivray’s investigation of urban space at the Rio 2016 Olympic Games [23], which comprise real-time walking observation and photography/video recording. I conducted naturalistic observations, emulating the role of a participant on match days in each of the cities, embodying a dual tourist-research role. Although acting as a participant, I remained detached from actual participants, watching social interactions from a distance, with no direct communication with the fans so as not to disturb or influence their behaviours should it become known that I was a researcher [39]. It was not possible to avoid joining the throngs of spectators entirely, getting caught up in the movements of crowds and the jubilant atmosphere, but it was precisely this experience I sought to understand from the participant perspective. I also attended one match between the USA and France at Fukuoka Hakatanomori Stadium on 2 October 2019. As a study of the event experience, walking as a method affords the advantage of being able to observe and directly experience the liminoid space, with exposure to the same stimuli and engaging in the same sense-making processes as other visitors. Indeed, using the walking method, I could experience placemaking and branding efforts, cultural performances, as well as observe how foreign visitors responded to and engaged with these. Moreover, live events are ephemeral in nature and direct engagement with the event at ground level through walking enables the researcher to record the event as it is seen by the participants. Through walking, the researcher can experience aspects of the event that may not be perceptible from the outside, such as “waymarking, barriers, security checks, and the use of sounds and senses to attract visitors to fixed spaces” [23], p. 282.

In each of the five chosen cities, I began my observations at the city’s main train station and, using the official visitor guides produced for the tournament, followed the travel information and map to the stadium, as a foreign spectator might do. I also followed physical markers along the routes, such as waymarking signage and branding. While on these routes, I paid close attention to the movement of other visitors and their interactions and engaged with placemaking elements along the way. Observations were recorded along the journey through photography, videography, and written notes. The collected data and their analysis are ordered chronologically and spatially, beginning at the station and moving through the liminoid space to the stadium.

Using walking as a method has its limitations. Observations and interpretations of the liminoid space are necessarily subjective and the analysis can only consider what I the researcher have observed. As such, this research can consider placemaking only from the visitor spectator’s perspective, and not the resident. Additionally, although I simulated the role of a participant, I did not engage with the other spectators to ask them questions about their experiences. While this means that they were not brought out of their liminoid experience, it also means that their views are not considered. However, as part of this ongoing research, foreign spectators’ experiences of the 2019 RWC have been discussed elsewhere [36]. The method is also highly subjective and my experience as participant travelling through the liminoid space will not have been the same as all other visitors. Moreover, as a Japanese speaker, I possessed an advantage in being able to read local signage and navigate easily. In the course of walking, I forced myself to use only tourist-focused materials and ignore Japanese signage or announcements. Finally, the walking method and observations only allowed for a cross-sectional analysis of the placemaking efforts within these liminoid spaces. This present study cannot speak to their long-term impacts on tourism development.

4. Results

In each of the selected host cities, observations commenced at the nearest train or metro station to their respective stadia. As can be seen in Table 1 below, in all five cases, the stadium was a considerable distance from the city centre. These distances were calculated using Google Maps, using each city’s main train terminal as the point to measure distance from the city centre to the stadium and the station recommended by the official visitors’ guides (discussed below) for the nearest train/metro station. In four of the five cities, it was required or advised to take a train out of the city, often from the main station. Only in Kumagaya did visitors travel directly from the main station to the stadium as this was a small city with only one station. These “Last Mile” distances show the limited space in which cities could promote themselves to visitors. With the exception of Fukuoka and Kumagaya, the other three cities had a route of less than one kilometre between the station and the stadium, typically leading away from the city and away from its attractions. While in Fukuoka and Kumagaya the distances between station and stadium were greater, free shuttle buses were offered, thereby reducing the time visitors spent in the cities. Given the limited space available to the cities for placemaking, observations carried out on the ground through walking methodologies sought to replicate the experience of the visiting spectator to understand how the spaces were leveraged.

Table 1.

Distances between selected 2019 RWC host cities and their stadia.

Observations began at the nearest station to the stadium in each host city, which I designated the “Arrival Point”. I then followed the stream of visitors out of the station to the stadium, taking photographs, recording videos, and making notes of my experiences and observations of placemaking efforts within these spaces. The below discussion begins by focussing on the host city and its Arrival Point, before moving onto the route to the stadium, followed by a discussion of the role of the “fan zones” in the liminoid space. The flow of this section follows the order in which the walks were made, mirroring my experiences as a spectator entering the liminoid space.

4.1. Host City and Arrival Point

In each of the five host cities, RWC branding could be found across the city centres in the form of banners on lamp posts and on roadside railings. While the matches would not take place in the centres of the cities, but rather on their outskirts, the centres were included in these branding efforts, raising the event’s visibility for its host communities and extending the festive atmosphere beyond the event venue. Although cities main stations were not the final Arrival Point, with the exception of at Kumagaya, they nonetheless served as a gateway to the city and the transfer point to the Arrival Point for visitors. Consequently, stations were decorated with tournament branding, localised to each host city. Volunteers could be found throughout the main stations including at designated welcome desks, where visitors could receive directions and pick up maps and guides (see Figure 1). These physical brochures provided visitors the information they needed to navigate the area and create their own experiences outside of the main experience-scape. At each station, I picked up an official visitor guide from the welcome desk. The pocket-sized guides provided basic information about the host city, suggested possible tourism attractions to visit or activities to undertake, gave information about the city’s fan zone(s), featured information about the matches held in the city and key information about the stadium including access, facilities and restrictions, and listed travel advice. The guides folded out to become an A4-sized map to the stadium, indicating clearly walking routes with times, station locations, shuttle bus stops, and useful facilities, including information points, taxi ranks, shops, ticket offices, first aid stations, and ATMs. The maps give a pictorial representation of the boundaries of the event: red dotted lines mark the approved routes spectators should travel along, while black lines indicated road restrictions, effectively separating the spectators from the exterior everyday world that busy road traffic would represent.

Figure 1.

Welcome desks at Kobe Station.

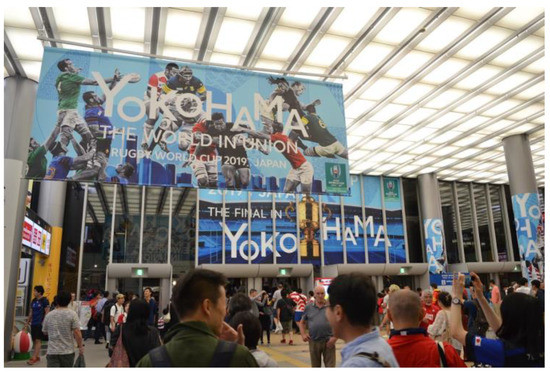

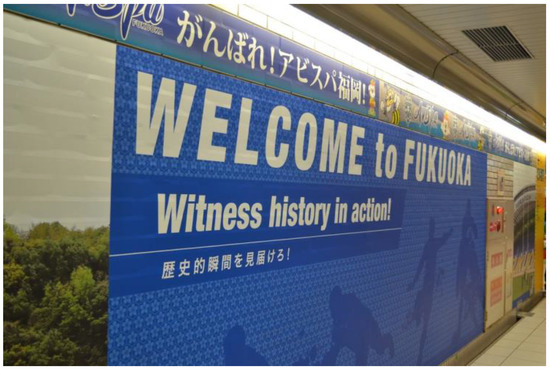

Using these guides, I followed the directions to the Arrival Point stations, although at all times clear tournament branding throughout the station and the steady stream of fans, alleviated any concern that I might be going in the wrong direction. Clear branding continued at the Arrival Point stations (Figure 2), although at these this branding was often not solely the official tournament design elements, but rather designs unique for each city that reflected local imagery and identity. For example, at Fukuokakūkō Station, the Arrival Point station for Fukuoka matches, passageway walls were decorated with images of the sports stadium along with mottos such as “Witness history in action!” and the tournament slogan “once in a lifetime”, emphasising the significance of the event for the city and for Japan (see Figure 3). As the designated Arrival Points for the matches, these stations served an official function for the event. While they were not part of the main experience-scape of the stadia grounds, they formed an experience-scape of their own, acting as a hub for visitors.

Figure 2.

City recognition in tournament branding at Shin-Yokohama Station.

Figure 3.

Welcome messaging at Fukuokakūkō Station.

From the Arrival Points, I followed the swarm of other rugby jersey-wearing spectators into the streets, with volunteers stationed regularly to point people in the right direction. Before even stepping out onto the route to the stadium, I was met with the hospitality and friendliness of these volunteers, stationed at regular intervals and welcome desks. Crowds entering the main concourses of the stations generated a bubbling of conversation, laughter, and palpable excitement. While the stations had some location specific branding, much of the imagery was standardised for the RWC. It was only after leaving the stations that individual host city approaches emerged. In the case of Osaka, matches were held at Japan’s oldest purpose-built rugby stadium, Hanazono Stadium, in Higashi-Osaka. Station shops advertised special rugby-themed snacks, including rugby ball-shaped baked goods from the local bakery. On leaving the station, visitors came face-to-face with an outdoor installation directly opposite the station greeting them with a welcome in bright pink flowers and a giant rugby ball floating overhead (Figure 4). This served as a stark contrast to the otherwise tidy and nondescript Japanese town. Although the stadium lay almost a kilometre away, the bright colours, novel designs, and throng of spectators combined to create a joyful atmosphere.

Figure 4.

Welcome display outside Higashi-Hanazono Station.

4.2. The Route to the Stadium

After leaving the Arrival Point, visitors crossed the threshold into the liminoid space of the route to the stadium, a space between everyday Japan and the tournament space, bringing the visitors into close contact with local communities and cultures, even if only in passing. Taking the city of Kumagaya as an example, all along the road from the train station to the fan zone, traditional Japanese drumming was played from atop large traditional floats stationed at regular intervals (Figure 5). Other elements of traditional Japanese culture were blended with the rugby experience too, such as an installation of traditional Japanese lanterns adorned with the emblems of all the participating teams, which blurred the lines between a traditional Japanese festival and a modern sports tournament (Figure 6). The use of Japanese motifs, different in each city, contributed to an enhanced sense of place, even if the event itself was international. These kinds of entertainments and their positioning along the routes contributed to the sense that this space was building towards the event. The march of rugby fans, moving with a singular purpose, combined with these elements evoked a sense of the religious ritual procession, in line with Falassi’s conceptualisation of festive behaviour [32]. This movement was not always constant, however, as people regularly stopped to look around, duck into bars, convenience stores and other shops, or stop to chat with friends and strangers. As a liminoid space, the route was not one where spectators were shepherded or kept moving by security or other officials, but rather a free-flowing space that facilitated different interactions and experiences. Moreover, although I carried out my observations alone, I very quickly felt part of the group.

Figure 5.

Drummers atop traditional Japanese floats in Kumagaya.

Figure 6.

Traditional Japanese lantern display in Kumagaya showing participating teams.

A conspicuous sight during observations was the amount of drinking that was taking place pre-match along the route to the stadia. During the tournament, these urban streets transformed from the everyday into noisy, festive environments. Convenience stores set up dedicated stalls outside their premises to sell cans of beer (Figure 7), with staff holding placards directing spectators to the beverages. Similar to observations made by Duignan, Down, and O’Brien at Rio 2016 [34], local bars and yakiniku (grilled meat) restaurants also took advantage of the situation, selling beer and snacks to fans on their walk to the stadium (Figure 8). In Higashi-Osaka, a yakiniku restaurant took advantage of the crowds, closing the building and setting up a stall out front. The smells of grilled chicken and beef filled the air, the sizzle of the meat on the grill competed with the murmur of the crowd, and foreign visitors attempted crude forms of sign language to make their orders.

Figure 7.

The “road to beer” in Kobe.

Figure 8.

Chains and independent businesses leverage the opportunity for sales in Kobe.

However, it was not just foreign fans standing outside the 7-Elevens, cans of Asahi in hand, but also Japanese spectators, and in many cases, there was intermingling between the groups. The large consumption of alcohol was also in line with Falassi’s description of festive behaviour and the notion that festivals bring members of a shared community together. The routes between stadia, thus, also encouraged or directly facilitated interactions and exchange between Japanese and non-Japanese, channelling them together, with the moving masses looking not too unlike a ceremonial procession or pilgrims converging on a holy site [32]. Gee, Jackson, and Sam have described the importance of alcohol consumption at sports events in the cultivation of the event atmosphere and a carnivalesque culture, finding that spectators consider drinking an integral part of the event [40]. It is not unsurprising that many sports events are sponsored by alcohol brands and the RWC was no exception, being sponsored by Heineken [41]. Despite the “official” presence of alcohol at the event through the sponsor, the consumption of beer and its contribution to the festive experience within the liminoid space felt less imposed, but rather facilitated by local businesses selling (Japanese, not Heineken) beer and consumed by the visitor. Indeed, the RWC differed from other events, where organisers’ control of the Last Mile route can prohibit businesses from selling their products and the urban landscapes are “appropriated by corporate sponsors” [42], p. 140. At the London 2012 Olympics, for example, street vendors and other traders along the Last Mile were heavily restricted, requiring special licences [42], p. 143. By contrast, local businesses appeared to be given full freedom to take advantage of the events.

As discussed at the beginning of this section, routes differed in length, and all were used differently in each host city. In all cases, visitors were channelled towards the stadia through the use of crowd-control barriers set up along the pavements. The barriers acted as a visual cue for the event towards which visitors were walking, while also acting as a separating device between the festive crowd and the everyday world. However, the channelling was limited to busy roads and people were not forced to keep moving, with security and other officials largely present only at the stadia. At Kumagaya, fans were channelled first towards a “fan zone” area, where they were presented with a choice of walking the remaining 3.7 km to the stadium or to take a free shuttle bus. I opted to take the bus, and while I queued for the next departure, there were traditional dance and music performances, giving visitors a taste of Japanese culture and the culture of that area without actively seeking it. In Higashi-Osaka, the public park opposite the rugby stadium was transformed into an entertainment space for visitors, with a troupe of traditional Japanese drummers moving through the crowd, and opportunities to engage with Japanese tradition through stalls offering activities (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Opportunities to engage in traditional arts and crafts outside Hanazono Stadium.

Within the narrow confines of the Last Mile space, a strong sense of communitas developed. Most spectators wore rugby shirts and other tournament merchandise, indicating the team they would be supporting. Japanese nationals often wore other countries’ shirts to show their support, and by the same token foreign visitors wore Japanese shirts. Although people arrived in defined groups, the sizes of these groups fluctuated as they came into contact with others, whether they supported the same team or not. Convenience stores, primarily a source of beer for spectators, also served as a venue for social interactions to take place, with groups of spectators congregating outside in the shop car parks. Outside of these organic interactions, volunteers engaged with spectators through waves and smiles, offering high fives, and asking spectators to pose behind tournament-branded cardboard frames for photos to go on social media.

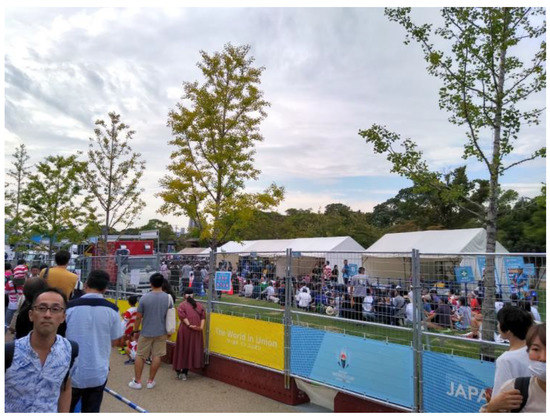

4.3. Fanzones

All host cities had “fan zones” during the tournament. Fan zones and other similar spaces are what are known as “Live Sites”, which provide an open, but highly regulated forum in which people can share in the enjoyment of an event [42]. These sites are specifically positioned to provide benefits for both visitors and host communities, often free to access and, thus, providing a way to enjoy the event without needing a ticket [43]. Live Sites are, thus, extensions of an event’s branding efforts [43], but also contribute towards placemaking as they “provide a means to interact with the host population and the opportunity to produce co-created experiences for event hosts, sponsors and spectators alike” [44], p. 20.

Although controlled spaces dominated by tournament branding, each fan zone felt very different. The locations of the fan zones determined the size of the space and influenced their footfall. In central Osaka, the fan zone occupied the whole of a major park and centred on a vast screen showing matches. Its central location enabled attendance from both local residents as well as foreign visitors; whole families turned out, taking spaces on the grass using tarpaulins and rugs as if attending a summer picnic. Within the fan zones, there were games and competitions, photo stands with cut-outs for visitors to put their heads through, and live entertainment scheduled throughout the day. In these spaces, the carnival or festival atmosphere was partly cultivated, a conscious effort on the part of the organisers. At the same time, however, I was struck by how unstructured the spaces were, with a large proportion of the sites given over to empty space in which fans could congregate and mingle, creating their own experiences. In Kumagaya, the fan zone was positioned partway along the route between the station and the stadium and served as the departure point for the free bus service to the stadium. The fan zone featured a temporary rugby museum, which told the story of rugby in the city, thereby embedding the event within the city’s sporting heritage and history, contributing to local pride of place as well as educating visitors (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Inside the rugby museum at Kumagaya’s fan zone.

Fukuoka’s fan zone was located outside of Hakata Station in central Fukuoka city. While not on the final walking route to the stadium, Hakata Station would have served as the main arrival point for visitors as this is where the Shinkansen (bullet train) arrives. This fan zone included a range of activities for both Japanese and non-Japanese visitors, including live entertainment, local food vendors, and rugby-themed activities. In Yokohama, Osaka, and Kobe, the fan zones were not located along their respective routes, but were instead at large public parks in the cities (Figure 11). This strategy encouraged visitors to travel into the city centre outside of the match, while also providing local residents that did not have tickets with a venue to engage with and view the tournament. Osaka’s fan zone was in the large central Tennoji Park, which proved so popular that visitors were turned away as it reached capacity (Figure 12).

Figure 11.

Scottish fans approach Kobe’s fan zone.

Figure 12.

Fan zone in Osaka’s Tennoji Park.

4.4. Community Engagement and Further Placemaking

Each host city utilised volunteers from the local community, amounting to a combined total of 13,000 volunteers across Japan, a record for the tournament [45]. Although the volunteers were utilised within the stadia grounds, their role extended beyond this official space. These volunteers could be found at train stations or lining the roads to the stadia, but they were also stationed in the main urban areas of the cities, away from the stadia themselves. Indeed, in Kobe for example, despite the stadium being a train journey from the town, volunteers could be found on many street corners in the city centre, ready to welcome visitors. In Kumagaya, even though many visitors opted for the free bus from the fan zone to the stadium, volunteers lined the entire route, ready to engage with not only those walking but also to wave at every bus that passed them (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Volunteers welcome visitors in Kumagaya.

The example of the volunteers reminds us that placemaking is something that should benefit the host community, making a place better than it was before. This article has focused on the elements of active engagement with visitors during the tournament, such as branding, entertainments, and the cultivation of a welcoming environment. Having focused solely on the spectator experience, this study cannot address this dimension of placemaking. However, other research has demonstrated benefits for host communities. In a survey of residents in all host cities, Sato et al. found that the event and its perceived impacts improved the psychological wellbeing of those residents [46]. We can see how local businesses leveraged the opportunity to increase their revenue, but these businesses also became part of the experience, contributing to the festive atmosphere of the routes to the stadium, blurring the boundaries between the everyday and the festival in that liminoid space. Moreover, it is important to recognise that the match attendees were not foreign tourists, as one million of the 1.6 million tickets were sold domestically [1]. Many of the spectators at matches would have been local residents themselves. Post-tournament, legacies of the 2019 RWC can be seen in infrastructural improvements in the cities, from renovated or fully rebuilt stadia [47] to decorative manhole covers in Higashi-Osaka, as seen in Figure 14, below.

Figure 14.

A commemorative RWC manhole in Higashi-Osaka.

5. Discussion

Before examining placemaking activities at the 2019 RWC in detail, it is worth considering the event within the context of other RWC tournaments that have been held before. As multi-city events, I suggest that these events have the potential to encourage more diverse tourism development in a country than a single-city event like the Olympics. However, have these events been successful at doing just this in the past?

The 1999 RWC was hosted by Wales and makes for an interesting case study, for although Wales was the official host, the tournament itself was held not only in Wales, but also England, Scotland, Ireland, and France for political and infrastructural reasons [48]. Consequently, tour operators could not advertise Wales specific tours, and spectators only actually visited Wales for certain matches. In spite of this, in securing the bid to host the event, Wales’s capital city Cardiff underwent significant infrastructural development, including the construction of a new stadium [48]. While the event sought to position Wales as a vibrant nation and its capital Cardiff as a modern European city, it struggled to articulate this through an event that was not held in Wales for the most part. This was not an issue in the case of Japan, which already had strong international recognition. On the contrary, the 2019 RWC not only strengthened this international profile, it also developed the identities of locations across the country.

The 2019 RWC has more in common with the 2011 RWC held in New Zealand, which explicitly sought to promote “Brand New Zealand”, improving the country’s international image and developing its inbound tourism industry [49]. The 2011 RWC matches were held across the country in a similar way to in 2019, but Dickson’s analysis of official reports finds that there is no clear indication of direct tourism growth arising from the tournament, with the official government report itself acknowledging that it would be difficult to identify tourism directly influenced by the RWC as opposed to other influencing factors [49]. Moreover, Dickson found that Auckland benefited more from visitor expenditure than other host cities [49]. Nevertheless, the event was found to have engaged well with communities and other stakeholders, including the indigenous Māori population, whose culture was showcased throughout the event. Through interviews with stakeholders, Werner, Dickson, and Hyde found that the 2011 RWC helped different stakeholders within a region to better communicate with one another, leading to a collaborative approach to the delivery of the tournament [50].

Although the 2019 RWC can be seen as an effort to promote the Japan brand internationally, we can observe the ways in which branding and placemaking occurred at a more local level. The stadia and their grounds comprised the main event space for the 2019 RWC and any branding therein was official tournament branding. This branding included the specific 2019 logo, which incorporated graphic representations of a red rising sun and Mount Fuji, as well as the word “Japan” within the branding text. Although this emphasised Japan as the tournament host and, therefore, a specifically Japanese curation and presentation of the event experience, within this space individual host city identities were not clearly articulated. Thus, for the purposes of placemaking, city branding efforts had to take place outside of the stadia. Match spectators had to walk a set route from the train station to the stadium, a liminoid space that is not officially part of the event but is part of the journey to that event. Moreover, as can be seen through the consumption of alcohol and festive atmosphere present in this space, it can be argued that as part of that journey, spectators began to enter into a festive mood. Simulating participation myself, I felt the excitement as I walked towards the stadium. While much of the atmosphere was created by the crowds themselves, it was supported and amplified by the festival elements arranged by the host city—the floats and the performances—as well as by the volunteers and local businesses. As I moved through the Last Mile, from the Arrival Point to the stadium, I felt an increase in the festive or carnivalesque atmosphere, marked by both the behaviours of the spectators themselves, who became more animated, as well as the entertainments that helped to generate this environment.

Anyone who has ever attended a football or rugby match in the UK and no doubt other countries too, knows that this liminoid space is regularly used by food vendors and small stallholders selling scarves and other merchandise. Such entrepreneurship has been discussed by Duignan, Down, and O’Brien [34], but it is the expression of local identity and brand building within this space that makes the 2019 RWC stand out. At each of the five host cities selected for this study, the space was used differently, contributing to distinct experiences in each destination. Such activities were not limited to the cities covered by this study; Kyodo News reported that several tourism agencies worked together to deliver an event in Kumamoto city for visiting rugby fans that showcased famous festivals of the region [51].

During my visit to these destinations, I observed certain limitations in placemaking strategies. Although each location provided distinct experiences in their respective liminoid spaces, not all cities effectively promoted themselves as brands. Rather, the entertainments imbued the event with a strong Japanese identity, while the friendliness of the volunteers and engagement with local businesses affirmed Japan’s reputation for hospitality. While this approach successfully communicated the concept of Japaneseness, it failed to effectively convey the unique characteristics of each city’s individual local culture. Although the printed visitor guides did provide some information about each host city’s background and attractions, this information did not always translate effectively to the liminoid Last Mile space. For instance, Higashi-Osaka is renowned in Japan as the home of the oldest rugby stadium and the country’s annual National High School Rugby Tournament. Along the route to the stadium, I noticed a statue of the city’s cartoon rugby player mascot Try-kun (Torai-kun), rugby ball motifs on the design of the city’s lamp posts, and several rugby-themed shops. Despite these visible elements of the city’s unique culture, they were not adequately communicated to foreign visitors. Similarly, while the host cities’ names were prominently displayed on large banners in the central stations of Yokohama and Kobe, the city-specific branding was not clearly articulated within the Last Mile routes. In comparison, the city of Kumagaya actively promoted its rugby connections.

6. Conclusions

The Last Mile has received comparatively little attention in events literature [23]. However, as this paper has shown, this liminoid space is an important part of the event experience and offers the potential for “placemaking in the periphery”. A range of approaches were employed in RWC host cities to engage with attendees and immerse them in a hybrid space that draws them into the festival/event atmosphere while encouraging them to engage with the destination itself. In the context of sports events tourism more widely, these findings are highly relevant. While it may not always be possible to promote the destination itself to visitors who travel directly to the event venue and leave soon after, the spaces around the venue itself are crucial. However, as I have argued, this space is not peripheral at all, but a key area of transition into the experience-scape, a liminoid space wherein visitors begin to behave in a festive convivial manner, creating the temporary communitas with other visitors making the journey to the venue.

This present research study only examined the direct experiences of visitors to the 2019 RWC host cities, and, therefore, cannot make empirically verifiable claims about the success of strategies or their long-term effects. However, the findings do suggest that the liminoid space played a clear role in creating a festive and convivial atmosphere that helped to create a sense of place. This has important implications for sports events tourism more widely, particularly in a post-pandemic context where destinations may need to find new ways to engage with visitors and promote their unique identity. As noted at the beginning of this article, the industry has recognised the need to be more sustainable and responsible in developing tourism as we emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic. Diversification of tourism destinations offers potential solutions to overtourism, and sports events can be leveraged to introduce new destinations to tourists, which in turn can use the events to develop their sense of place. While the strategies adopted by the host cities during the 2019 RWC may not be suitable for every sports event, the use of liminoid spaces to immerse tourists in a hybrid space that draws them into the festival or event atmosphere while encouraging them to engage with the destination itself is an innovative approach that could be adapted to other events. Future research should evaluate the longitudinal impacts of the RWC on host cities’ efforts to develop tourism.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data collected for this study is based on naturalistic observations. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Kyoto Institute, Library and Archives, who hosted me during my time in Japan in the autumn and winter of 2019/20, and the support of all colleagues at the Institute.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- EY Japan. Rugby World Cup 2019: Review of Outcomes; EY Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- JapanGov Hosting the First Rugby World Cup in Asia. Available online: https://www.japan.go.jp/tomodachi/2017/summer2017/hosting_the_first_rugby_world_cup.html (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Nikkei Asia. Rugby World Cup Becomes Money Spinner. Available online: https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Rugby-World-Cup-becomes-money-spinner (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Rugby World Cup. RWC 2019 Host Cities. Available online: https://www.rugbyworldcup.com/2019/cities (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Japan Sports Agency. Regional Revitalization through Sports Tourism. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/sports/en/b_menu/policy/economy/rrstourism.htm (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Hong, G.H.; Schneider, T. Shrinkanomics: Policy Lessons from Japan on Aging. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2020/03/shrinkanomics-policy-lessons-from-japan-on-population-aging-schneider (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Japan Tourism Agency. Tourism Nation Promotion Basic Law. Available online: https://www.mlit.go.jp/kankocho/en/kankorikkoku/index.html (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- UNWTO/WTCF. City Tourism Performance Research Report for Case Study “Tokyo”; UNWTO and World Tourism Cities Federation: Madrid, Spain; Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The Japan Times. Japan Needs to Prove Rugby World Cup’s “Once in a Lifetime” Catchphrase Wrong. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/sports/2019/10/21/rugby/japan-need-prove-rugby-world-cups-lifetime-catchphrase-wrong/ (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Palacios-Florencio, B.; Santos-Roldán, L.; Berbel-Pineda, J.M.; Castillo-Canalejo, A.M. Sustainable Tourism as a Driving Force of the Tourism Industry in a Post-Covid-19 Scenario. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 158, 991–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensah, E.A.; Boakye, K.A. Conceptualizing Post-COVID 19 Tourism Recovery: A Three-Step Framework. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2023, 20, 37–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmonsbey, J.D.; Tichaawa, T.M. Using Non-Mega Events for Destination Branding: A Stakeholder Perspective. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2019, 24, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J.; Larsen, J. The Tourist Gaze 3.0; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4462-5992-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, C.J. Gaikokujin ragubī fan kara mita kyōto – ragubī wārudo kappu 2019 nihon taikai no kankyaku no kankō katsudō wo chūshin ni [Kyoto through the eyes of foreign rugby fans: Tourism activities during the Rugby World Cup 2019]. Kyōto furitsu gaku rekisaikan kiyō 2022, 5, 93–120. [Google Scholar]

- Fourie, J.; Santana-Gallego, M. The Impact of Mega-Sport Events on Tourist Arrivals. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1364–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, S.B.; Holladay, J.S. Should Cities Go for the Gold? The Long-Term Impacts of Hosting the Olympics. Econ. Inq. 2012, 50, 754–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, J.; Robertson, M.; Ali-Knight, J. Festivals and Events: Beyond Economic Impacts. Event Manag. 2008, 11, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalip, L. Towards Social Leverage of Sport Events. J. Sport Tour. 2006, 11, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalip, L.; Green, C.; Hill, B. Effects of Sport Event Media on Destination Image and Intention to Visit. J. Sport Manag. 2003, 17, 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalip, L.; Costa, C.A. Sport Event Tourism and the Destination Brand: Towards a General Theory. Sport Soc. 2005, 8, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, D.C.; Toohey, K.; Bruun, T. International Sport Event Participation: Prior Sport Involvement; Destination Image; and Travel Motives. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2007, 7, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou, K.; Vogt, C. The Interrelationship between Sport Event and Destination Image and Sport Tourists’ Behaviours. J. Sport Tour. 2007, 12, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duignan, M.B.; McGillivray, D. Walking Methodologies, Digital Platforms and the Interrogation of Olympic Spaces: The ‘#RioZones-Approach. ’ Tour. Geogr. Int. J. Tour. Space Place Environ. 2019, 23, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. From Place Branding to Placemaking: The Role of Events. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2017, 8, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A.A. Tourism Planning and Place Making: Place-Making or Placemaking? Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 448–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brito, M.P.; Richards, G. Guest Editorial. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2017, 8, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.C.; Mendes, J.; do Valle, P.O.; Scott, N. Co-Creation of Tourist Experiences: A Literature Review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 369–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakis, N.D.; Alexandris, K.; Tsigilis, N.; Karvounis, S. Predicting Spectators’ Behavioural Intentions in Professional Football: The Role of Satisfaction and Service Quality. Sport Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamond, I.R.; Moss, J. What Is Liminality in Critical Event Studies Research? In Liminality and Critical Event Studies: Borders, Boundaries, and Contestation; Lamond, I.R., Moss, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 17–33. ISBN 978-3-030-40256-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lamond, I.R.; Moss, J. Liminality and Critical Event Studies: Borders, Boundaries, and Contestation; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-40256-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Li, Y.; Wood, E.H.; Senaux, B.; Dai, G. Liminality and Festivals—Insights from the East. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 80, 102810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falassi, A. ; Time Out of Time: Essays on the Festival; University of New Mexico Press: Albuqueque, NM, USA, 1987; ISBN 978-0-8263-0933-4. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J. Consuming Places; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-1-134-82967-5. [Google Scholar]

- Duignan, M.B.; Down, S.; O’Brien, D. Entrepreneurial Leveraging in Liminoidal Olympic Transit Zones. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 80, 102774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, I.; Brown, L.; Shipway, R. Meaning Not Measurement: Using Ethnography to Bring a Deeper Understanding to the Participant Experience of Festivals and Events. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2010, 1, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moles, K. A Walk in Thirdspace: Place, Methods and Walking. Sociol. Res. Online 2008, 13, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.; Urry, J. Enacting the Social. Econ. Soc. 2004, 33, 390–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springgay, S.; Truman, S.E. Walking Methodologies in a More-than-Human World: WalkingLab; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-138-29376-2. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, N. Naturalistic Observations. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods; Allen, M., Ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 1082–1084. ISBN 978-1-4833-8143-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, S.; Jackson, S.J.; Sam, M. Carnivalesque Culture and Alcohol Promotion and Consumption at an Annual International Sports Event in New Zealand. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2016, 51, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heineken. Heineken Announces Worldwide Partnership for Rugby World Cup 2019(TM). Available online: https://www.theheinekencompany.com/newsroom/heineken-announces-worldwide-partnership-for-rugby-world-cup-2019tm/ (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Osborn, G.; Smith, A. Olympic Brandscapes: London 2012 and the Seeping Commercialisation of Public Space. In The London Olympics and Urban Development: The Mega-Event City; Poynter, G., Viehoff, V., Li, Y., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 139–153. ISBN 978-1-138-79494-8. [Google Scholar]

- McGillivray, D.; Frew, M. From Fan Parks to Live Sites: Mega Events and the Territorialisation of Urban Space. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 2649–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGillivray, D. Mixed Reality at Mega Events: Bringing the Games to You? Cult. Olymp. Issues Trends Perspect. 2011, 13, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- The Japan Times. 13,000 “Team No-Side” Volunteers Ready for Rugby World Cup. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/sports/2019/09/11/rugby/13000-team-no-side-volunteers-ready-rugby-world-cup/ (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Sato, S.; Kinoshita, K.; Kim, M.; Oshimi, D.; Harada, M. The Effect of Rugby World Cup 2019 on Residents’ Psychological Well-Being: A Mediating Role of Psychological Capital. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanazono Rugby Museum. Stadium Before-After. Available online: https://hanazono-rugby-hos.com/museum-en/before-after/ (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Jones, C. Mega-Events and Host-Region Impacts: Determining the True Worth of the 1999 Rugby World Cup. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2001, 3, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, G. State Rationale, Leveraging Strategies and Legacies: Rugby World Cup 2011. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2017, 9, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, K.; Dickson, G.; Hyde, K.F. Mega-Events and Increased Collaborative Capacity of Tourism Destinations: The Case of the 2011 Rugby World Cup. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyodo News. Japanese Tourism Industry Banking on Rugby World Cup Boost. Available online: https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2019/08/d2864b2df332-japanese-tourism-industry-banking-on-rugby-world-cup-boost.html (accessed on 21 January 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).