Abstract

Methoxy radicals (CH3O•), formed as intermediates during methane oxidation, may play an underexplored but locally significant role in the atmospheric oxidation of dimethyl sulfide (DMS), a key sulfur-containing compound emitted primarily by marine phytoplankton. This study presents a comprehensive computational investigation of the reaction mechanisms and kinetics of DMS oxidation initiated by CH3O•, using density functional theory B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd), CCSD(T)/6-311++G(3df,3pd), and UCBS-QB3 methods. Our calculations show that DMS reacts with CH3O• via hydrogen atom abstraction to form the methyl-thiomethylene radical (CH3SCH2•), with a rate constant of 3.05 × 10−16 cm3/molecule/s and a Gibbs free energy barrier of 14.2 kcal/mol, which is higher than the corresponding barrier for reaction with hydroxyl radicals (9.1 kcal/mol). Although less favorable kinetically, the presence of CH3O• in localized, methane-rich environments may still allow it to contribute meaningfully to DMS oxidation under specific atmospheric conditions. While the short atmospheric lifetime of CH3O• limits its global impact on large-scale atmospheric sulfur cycling, in marine layers where methane and DMS emissions overlap, CH3O• may play a meaningful role in forming sulfur dioxide and downstream sulfate aerosols. These secondary organic aerosols lead to cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) formation, subsequent changes in cloud properties, and can thereby influence local radiative forcing. The study’s findings underscore the importance of incorporating CH3O• driven oxidation pathways into atmospheric models to enhance our understanding of regional sulfur cycling and its impacts on local air quality, cloud properties and radiative forcing. These findings provide mechanistic insights that improve data interpretation for atmospheric models and extend predictions of localized variations in sulfur oxidation, aerosol formation, and radiative forcing in methane-rich environments.

1. Introduction

Methane (CH4) is a significant greenhouse gas, with atmospheric concentrations that have more than doubled since preindustrial times [1], contributing to global warming due to its potent radiative forcing [2]. As the simplest alkane, CH4 also serves as a critical feedstock for chemical processes, and its atmospheric oxidation plays a central role in climate and air quality studies. Anthropogenic activities, such as agriculture and fossil fuel extraction, contribute up to 60% of methane emissions, with 40% stemming from agricultural sources [3]. The oxidation of CH4 in the atmosphere, initiated by hydroxyl radicals (•OH) via hydrogen atom abstraction (HAA), leads to the formation of methyl radicals (CH3•) that subsequently react with molecular oxygen (O2) to form methyl peroxy-radicals (CH3OO•). These species can further react with nitric oxide (NO•) to generate the methoxy radical (CH3O•) via the CH3OO• + NO• → CH3O• + NO2 reaction [4,5]. Methoxy radicals are significant intermediates in atmospheric chemistry, particularly in the oxidation of dimethyl sulfide (DMS), a sulfur compound emitted by marine phytoplankton [6]. While DMS can be emitted from terrestrial sources and human activities [7,8,9,10,11], the ocean remains the dominant source. The chemical reaction of DMS produces sulfur dioxide (SO2) and sulfur-containing organic intermediates, contributing to the atmospheric sulfur cycle. This pathway plays a vital role in the formation of sulfate aerosols, which can act as cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) and influence cloud properties and radiative forcing. Although the oxidation of DMS by HO• and nitric oxide radicals (NO•) is well-documented, the role of CH3O• remains virtually unexplored. This pathway should be considered along with its broader impacts of sulfur chemistry on atmospheric processes, air quality, and radiative forcing.

Given their short atmospheric lifetime and high reactivity, CH3O• are localized intermediates that primarily influence sulfur cycling in regions where DMS and CH4 emissions overlap [12,13,14,15,16]. Computational investigations of reaction mechanisms, such as HAA and oxygen atom transfer (OAT), provide valuable insights into these processes. This study explores the potential role of CH3O• in catalyzing DMS oxidation, highlighting its potential to enhance the formation of secondary pollutants such as sulfate aerosols and sulfuric acid.

Methane concentrations continue to rise due to both anthropogenic and natural sources [17,18], particularly in localized areas like cattle barns, coal mines, and fossil fuel infrastructure venting systems. As the primary component of natural gas—comprising approximately 87% by volume—methane has become increasingly prevalent in the U.S., which is now one of the world’s leading producers of natural gas [19]. Despite lower atmospheric concentrations compared to carbon dioxide, methane is a much more potent greenhouse gas due to its higher absorptivity of infrared radiation per molecule. Methane’s global warming potential is approximately 84 times greater than that of carbon dioxide (CO2) over a 20-year timescale, making it a critical target for climate mitigation [2]. Its impact is driven not only by direct radiative forcing but also by its indirect influence on atmospheric chemistry, particularly in the formation of sulfate aerosols through DMS oxidation. Understanding methane’s dual role as a potent greenhouse gas and a key modulator of aerosol formation is essential for refining our understanding of CCN formation, impacts on cloud properties and subsequent radiative forcing.

Methoxy radicals, produced during methane oxidation, react with DMS to form intermediates like methyl-thiomethylene (MSM) [20], radical (CH3SCH2•) which is further oxidized to produce sulfur dioxide (SO2) and sulfur-containing organic compounds [21]. This pathway is crucial in the formation of sulfuric acid and secondary organic aerosols (SOAs) [22,23,24], which impact atmospheric chemistry and global climate. This study explores an alternative HAA route, where CH3O• catalyzes the oxidation of DMS, leading to the formation of the MSM intermediate. While the oxidation of DMS by hydroxyl and nitrate radicals is well-established, this is the first investigation to explore the possibility of CH3O• driving the DMS oxidation.

Given the anthropogenic increase in methane precursor emissions from hotspots such as cattle farms, fossil fuel production, and landfills, the production of CH3O• through methane oxidation may be increasing. Methoxy radicals have a noticeably short atmospheric lifetime, typically on the order of milliseconds [25]. Under standard atmospheric conditions at the Earth’s surface (298.15 K and 1 atm), their reaction with O2 is extremely rapid, with a rate constant of approximately 1.92 × 10−15 cm3/molecule/s [25]. This short lifetime limits their influence in regions where methane oxidation and DMS emissions coincide, such as marine environments. Despite their rapid decay, CH3O• plays a crucial role in DMS oxidation, which contributes to sulfate aerosol formation, CCN formation and local radiative forcing [26].

Consistent with prior experimental and theoretical work of organosulfur oxidation, alkoxy radicals in sulfur-containing systems (including CH3O• and CH3SCH2O•) react on atmospheric timescales, with effective bimolecular rate constants typically on the order of 10−13 to 10−11 cm3/molecule/s [20,27,28]. However, specific rate constants for the interaction between DMS with CH3O• remain poorly understood, highlighting the need for further experimental and theoretical research. The reaction between DMS with CH3O• produces SO2 and various sulfur-containing organic compounds, influencing the atmospheric sulfur cycle. This pathway is particularly important for understanding the formation of secondary pollutants like sulfate aerosols and their broader impacts on air quality and radiative forcing [6,29].

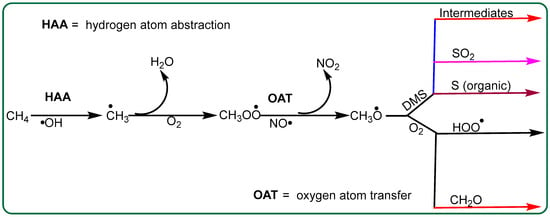

Methoxy radicals are primarily produced through the reaction of CH3OO• with NO•. Methylperoxyl radicals themselves are formed when CH3• reacts with O2. Methane oxidation in the atmosphere is primarily initiated by •OH, which is responsible for approximately 90% of the total annual methane removal globally [30,31]. Since CH3O• is commonly formed in the atmosphere [32], studying its reaction with DMS is essential for understanding the atmospheric cycle of methane and its interconnected role in atmospheric chemistry. In light of the difficulties associated with experimentally determining rate constants for larger alkoxy radicals, computational chemistry offers an effective approach for exploring reaction mechanisms and energy barriers [27]. This study uses density functional theory (DFT) to investigate these processes, with the proposed reaction pathway for methane oxidation to CH3O• outlined in Scheme 1.

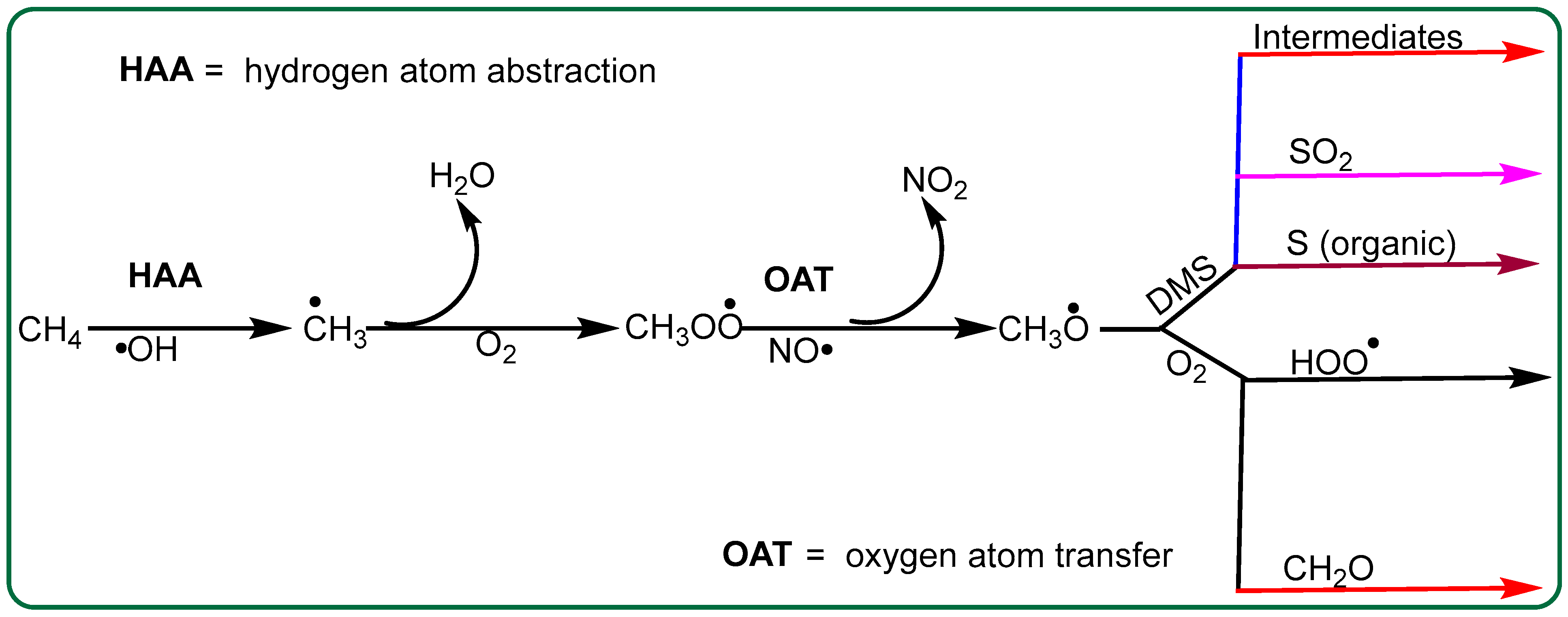

Scheme 1.

Primary reaction pathways leading to the formation of CH3O• from methane oxidation initiated by •OH radicals. The process begins with hydrogen abstraction from methane by forming methyl radicals, which subsequently react with oxygen to generate methyl peroxy-radicals. These peroxy radicals undergo OAT with nitric oxide, producing CH3O• and nitrogen dioxide. Additionally, CH3O• play a role in atmospheric sulfur cycling, as they react with dimethyl sulfide, leading to the formation of SO2 and sulfur-containing organic compounds. This pathway highlights the interplay between methane oxidation and sulfur chemistry in the atmosphere.

2. Computational Methods

Density Functional Theory (DFT), specifically employing the hybrid B3LYP exchange-correlation functional [33,34,35] with the D3(BJ) empirical dispersion correction [36,37,38], was utilized to investigate the chemical interactions between DMS and CH3O•, CH4 and •OH, and DMS and •OH. These computations were performed uniformly and consistently using the Gaussian 16 Revision C.01 suite of programs [39]. Geometry optimizations and vibrational frequency calculations for all reactants, transition states, and products were performed at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) level of theory. Higher-level electronic structure calculations were employed to refine reaction energetics. CCSD(T)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) calculations [40,41,42,43] were performed exclusively as single-point electronic energy evaluations on the B3LYP-D3(BJ) optimized geometries. Thermochemical contributions (zero-point, thermal, and entropic corrections) were obtained from the corresponding B3LYP-D3(BJ) vibrational frequency calculations and combined with the CCSD(T) electronic energies following standard Gaussian composite thermochemistry procedures, yielding CCSD(T)//B3LYP-D3(BJ) Gibbs free energies. In addition, CBS-QB3 composite calculations were carried out using the Gaussian CBS-QB3 protocol [44], which defines a calibrated and internally consistent sequence of geometry optimization, vibrational frequency, and correlated single-point energy calculations through a single composite keyword. Gibbs free energies obtained from CBS-QB3 therefore correspond to internally consistent CBS-QB3 composite thermochemistry, rather than a mixing of unrelated electronic and vibrational methods. All Gibbs free energies (ΔG and ΔG‡) were evaluated at 298.15 K and 1 atm and are reported relative to the separated reactants.

All species were optimized at the appropriate charge and spin multiplicity. Closed-shell molecules (e.g., CH4, DMS, H2O) were treated as neutral singlets, whereas radical intermediates and transition states (e.g., CH4O•, •OH, CH3•, and sulfur-centered radicals) were modeled as neutral doublets. A complete list of charges and spin states for all species included in this work is provided in the Supporting Information.

All Gibbs free energies (ΔG) were computed at 298.15 K and 1 atm, incorporating thermal corrections derived from vibrational frequency calculations. Energies are reported relative to the separated reactants, providing a consistent reference frame for all species. The relative Gibbs free energy profiles were analyzed to identify rate-determining steps and evaluate the overall feasibility of the catalytic pathways. Basis set superposition error (BSSE) corrections were evaluated using the counterpoise method for selected pre-reactive complexes and found to be small (<0.3 kcal/mol) when using the 6-311++G(3df,3pd) basis set. Because the reactions of interest involve covalent bond formation and cleavage rather than weak intermolecular binding, and because the reported results rely on Gibbs free energies that include much larger thermal and entropic contributions, explicit BSSE corrections were not applied. The reaction rate constant (k) for the oxidation of DMS by CH3O• was computed using Transition-State Theory (TST), incorporating Gibbs free energies derived from single-point CCSD(T) thermal energy calculations combined with partition function evaluations.

Stationary points along the reaction pathways were characterized as minima or transition states (TSs) based on their vibrational frequencies, with zero imaginary frequencies for minima and one imaginary frequency for TSs. Transition states were validated through intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations to confirm their connectivity to the appropriate reactant and product species [45,46]. Geometries were optimized without imposing symmetry constraints, and wavefunction stability was verified using the stable=opt keyword for Gaussian 16 to ensure that the optimized electronic wavefunction corresponded to a true local minimum. Reactions were referenced to separated reactants; the pre-reactive complex was characterized but not included in equilibrium modeling. Internal rotors were treated within the harmonic approximation.

Kinetics Calculations. We calculate the reaction rate (k) constant by using the explicit transition state theory (TST) expression:

where (TST is the Transition State Theory) is the rate constant (in cm3/molecule/s), is the bimolecular scaling factor, (Here, the factor arises from the bimolecular standard-state correction in the transition state theory expression for gas-phase reactions [47]. is the Boltzmann constant (in J/K), is the absolute temperature (in K), is Planck’s constant (in Js), Vm is the molar volume (m3/mol: ideal gas law), , qA, qB are the unitless partition functions for TS and reactants from Gaussian output (Total Bot) files, ΔE‡ is the energy barrier for the reaction, R is the gas constant (in cal/K mol).

Following the application of the TST expression to evaluate rate constants for key reaction pathways, we conducted a series of quantum chemical calculations to characterize each species and transition state involved in the oxidation of DMS by methoxy radicals, as well as the precursor steps originating from methane oxidation. These calculations span geometry optimizations, frequency analyses, intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) confirmations, and high-level single-point energy refinements.

For all calculations, tight convergence criteria were applied, and superfine numerical grids were employed to improve the precision of numerical integration. The unrestricted (UCBS-QB3) and restricted (RCBS-QB3) [48] wavefunction methodologies were applied for paramagnetic and diamagnetic species, respectively, to ensure a treatment with high accuracy for both open- and closed-shell systems. These computational methods were chosen for their reliability in modeling complex molecular geometries, reaction energetics, and transition states, providing robust and consistent insights into the mechanisms and energy barriers relevant to atmospheric chemistry [40,41,42,48]. Among the methods used in this study, the CCSD(T)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) and CBS-QB3 single-point calculations represent the highest levels of theory and therefore provide the most reliable estimates for activation barriers and reaction thermochemistry. These values should be considered the most accurate for comparison with experimental measurements.

A summary of all computational efforts, including the type of calculation, level of theory used, and their specific purpose, is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Completed Quantum Chemical Calculations for DMS Oxidation Pathways.

3. Results and Discussion

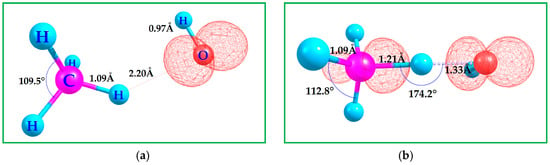

Computed Methane Geometry. The tetrahedral structure of the methane molecule was computed at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) level of theory in the gas phase to analyze its geometry. The calculated H–C–H bond angles measure 109.5°, while the C–H bond lengths are 1.09 Å. In this study, methane undergoes conversion to CH3O•, which subsequently plays a role in the oxidation of DMS. Methane is introduced into the atmosphere and undergoes oxidation via a series of reactions (Scheme 1). While the majority of methane molecules are oxidized within the troposphere, a portion ascends to higher altitudes, contributing to stratospheric methane chemistry. Using three theoretical methods, B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd), CCSD(T)/6-311++G(3df,3pd), and RCBS-QB3, the C–H bond dissociation enthalpy (BDE) of methane was calculated to be 103.5, 103.4, and 105.4 kcal/mol, respectively.

3.1. Binding CH4 with •OH

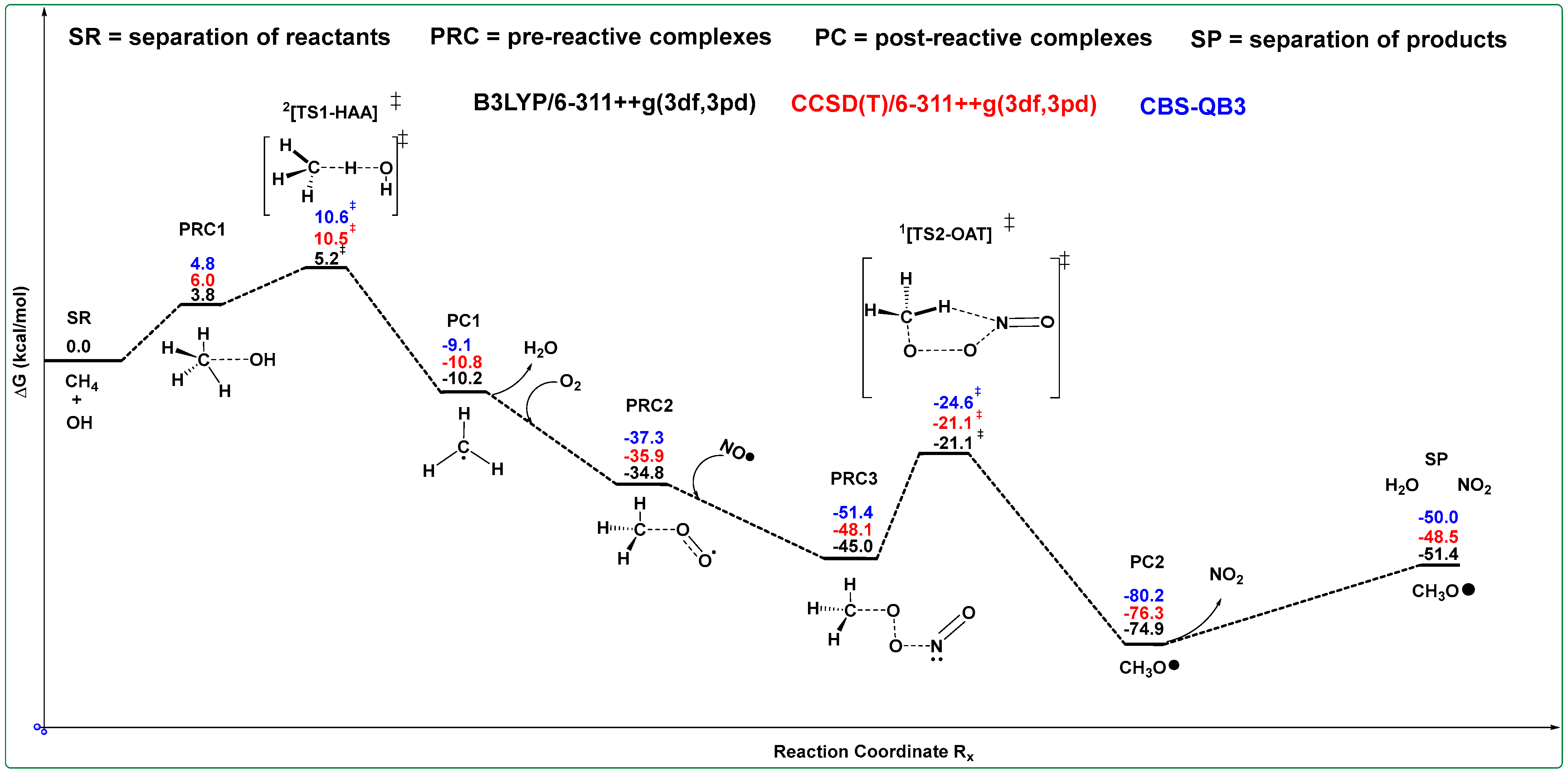

The hydroxyl radical substrate is within 2.20 Å of the methane molecule, Figure 1. The optimized CH4 with HO• C-H and H-O bond lengths are 1.09 and 0.97 Å, respectively, Figure 1, which is consistent with the free molecules “a”. Figure 1 “b” shows the transition state geometry for methane reacting with an HO•. The bond lengths and spin-density distribution define the energy barrier associated with methane C–H activation, providing key insight into the formation of CH3O•, the species that subsequently drives DMS oxidation. At the current working level of theory, B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd), the binding Gibbs free energy of the hydroxyl radical with CH4 is endergonic across all three computational methods (see Scheme 2), relative to the separated reactants. Scheme 2 collects the computed Gibbs free energy results of methane C-H activation by the HO• via HAA, which produces water and a free methyl-radical species [49]. The optimized geometries of all species discussed in Scheme 2 are provided in the Supporting Information (SI). The first transition state of methane to methoxy is the HAA mechanism, known to be a radical pathway involving formal one-electron (1e−) reduction, which is the reduction of one electron (1e−) of the methane species. The calculated Gibbs free energies of methane C-H activation with HO•, 2[HAA-TS1]‡ is computed to be consistent with other typical energy barriers at 1.0 atm and 298.15 K for the three level of theories employed, Scheme 2 [50,51]. Gibbs free energies in Scheme 2 are reported relative to the separated CH4 + •OH reactants, even though the intermediates and products differ in composition. The pre-reactive CH4…•OH complex is slightly higher in free energy due to the entropic cost of association, whereas the transition state exhibits the expected positive free-energy barrier for hydrogen abstraction. The CH3• + H2O products are substantially lower in ΔG, consistent with the strength of the newly formed O-H bond.

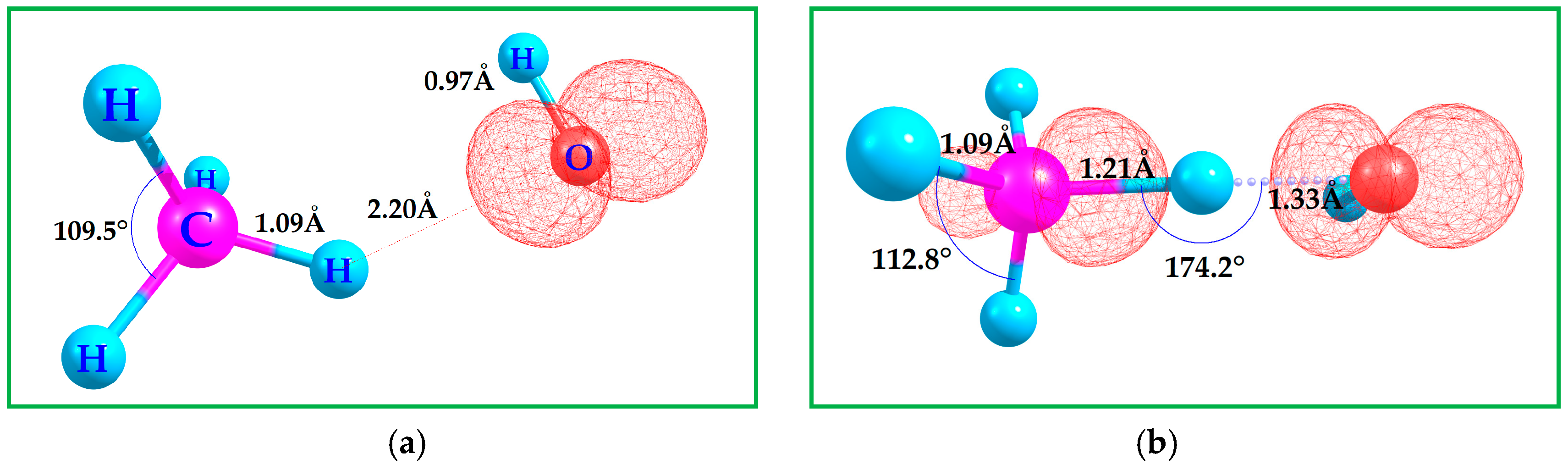

Figure 1.

(a) Computed B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) ground state geometry of methane CH4 and •OH. (b) C-H activation transition state geometry. Contour value of the spin density plot is 0.020 a.u. Red = positive spin density.

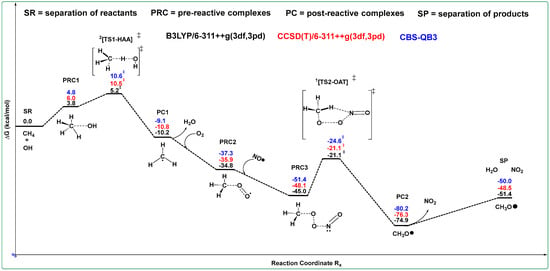

Scheme 2.

Transition state energy (‡) diagram for the reaction between CH4 with •OH at the current levels of theory B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd), CCSD(T)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) and CBS-QB3; black, red, and blue, respectively.

The UCBS-QB3 high accuracy TS is computed to have a reasonable energetic barrier of only 4.8 kcal/mol relative to the adduct, Scheme 2. The UCBS-QB3 and CCSD(T)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) level of theory TSs ΔΔG‡ = 5.4 and 5.3 kcal/mol higher in comparison with the corresponding B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) bases set. The methyl radical species may then radically rebound to an incoming hydroxyl radical species for atmospheric methanol production. The hydroxyl-radical has a standard oxidation–reduction potential energy of 2.8 eV that is only lower than F2 (g) + 2e− → 2F− (aq.) 2.87 eV, which demonstrates that hydroxyl-radical oxidation characteristics are non-selective and allow the •OH to react with almost all types of substances in the atmosphere [52,53,54]. Atmospheric methanol (CH3OH) is significantly more thermodynamically stable than CH3OO•; however, the rebound pathway leading to methanol formation (CH3• + •OH → CH3OH) is not part of the mechanistic sequence illustrated in Scheme 2 and is therefore not included in the potential energy surface (PES). Scheme 2 specifically focuses on the methane-initiated steps that progress from CH4 oxidation to CH3OO• and subsequently to CH3O•. For instance, in the atmosphere, the average concentration of hydroxyl radical is 1.09 × 106 and 1.1 × 105 molecules cm−3 in the troposphere and lower stratosphere [15], respectively, in contrast to oxygen molecules with concentrations of 5.17 × 1018 molecules cm−3 with an atmospheric pressure of 1.0 atm, temperature 298.15 K, and 1 cm3 of air with a constant of 21% oxygen molecules. It is 1012 (in troposphere: 5.17 × 1018/1.09 × 106) times more likely that molecular oxygen will react with the methyl radical over that of the hydroxyl radical. The calculation of molecular oxygen concentration is outlined in the Supporting Information (SI).

Formation of the methylperoxy radical proceeds through the well-established barrierless association of CH3• with O2 to produce CH3OO•, as reported in both experimental and theoretical studies [55,56]. The main purpose of this paper is to show that methane molecules can oxidize DMS through CH3OO• radical species, which is then successively attacked by nitric oxide through a bimolecular reaction that produces methoxy radical via OAT TS, Scheme 1. The binding of methylperoxyl and nitric oxide, CH3OO• + NO• → CH3OONO → CH3O• + NO2, is computed to be exergonic with respect to separated reactions. In Scheme 2, all Gibbs free energies are reported relative to the separated CH4 + •OH reactants, which serve as the reference state for the entire PES. Nitric oxide (NO•) is coordinated to methylperoxyl radical through the nitrogen atom in a κ1-N-bound to the terminal oxygen or side-to-side stacking of the N-O (nitric oxide) molecule with the molecular oxygen in a η4 fashion [57]. The κ1-N-bound fashion with an exergonic (ΔΔG = −25 kcal/mol) below the side-to-side stocking species, which may suggest that OAT transition state is most likely to occur over the cycloaddition transition state. The higher stationary point geometries are collected in the Supporting Information (SI).

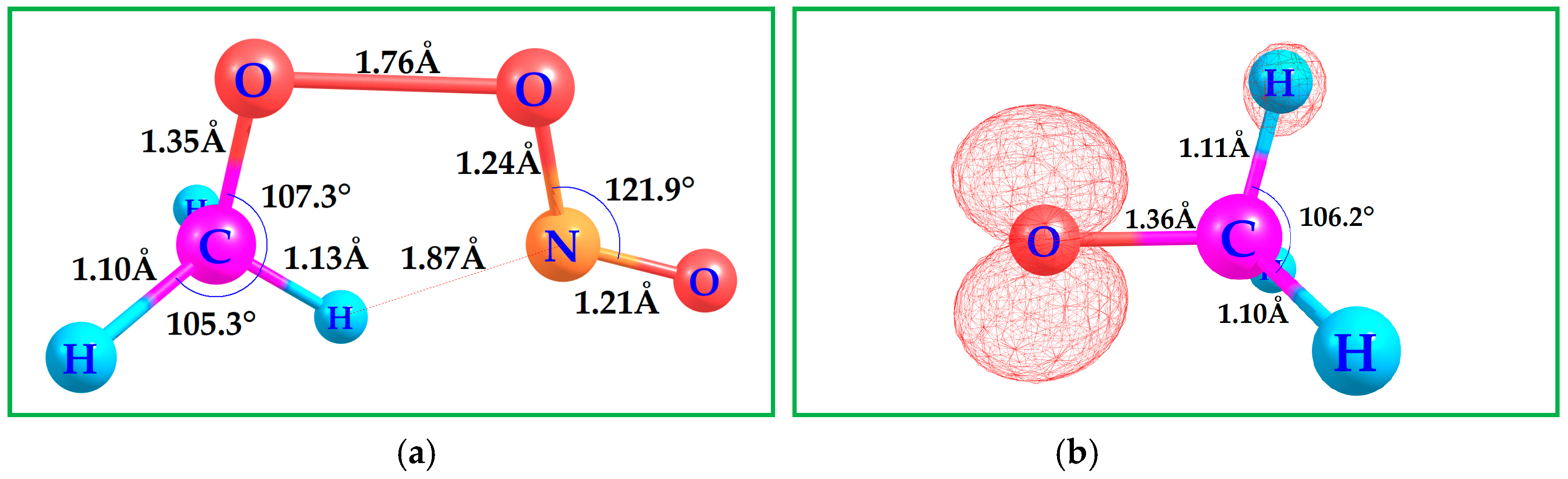

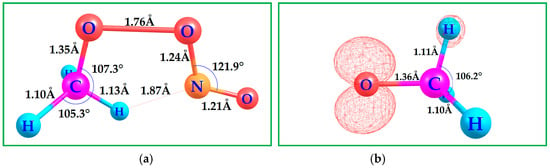

The electronic isomers of CH3OONO may undergo OAT facilitated by a five-member ring structure, as shown in Figure 2 “a”. This process is followed by the dissociation of NO2, leading to the formation of a methoxy radical. The NO2 molecule can further dissociate under ultraviolet (UVC) light, producing NO• and a highly reactive singlet oxygen-atom. This singlet oxygen-atom can then combine with molecular oxygen to form ozone (O3) in the troposphere.

Figure 2.

(a) Computed B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) transition state geometry for the OAT reaction between the CH3OO• and NO•. (b) CH3O• radical. Contour value of the spin density plot is 0.020 a.u.: Red = positive spin density. The geometry emphasizes key structural changes associated with the formation of CH3O• and supports the exergonic nature of this reaction under atmospheric conditions, reinforcing the plausibility of CH3O• generation via NO• mediated processes.

The OATs contiguously with the Gibbs free energy results of nitric oxide, which involve CH3OO• are collected in Scheme 1, and the relevant B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) transition state geometry, Figure 2 “a”, the higher stationary point transition state geometries are collected in the SI. The ΔΔG‡ difference between the CCSD(T)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) and the UCBS-QB3 TSs are 0.0 and 3.5 kcal/mol equal or above the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) TS2‡. The Gibbs free energy calculations indicate that the formation of the methoxy radical is spontaneous relative to TS2‡, regardless of the computational model employed, as illustrated in Scheme 2.

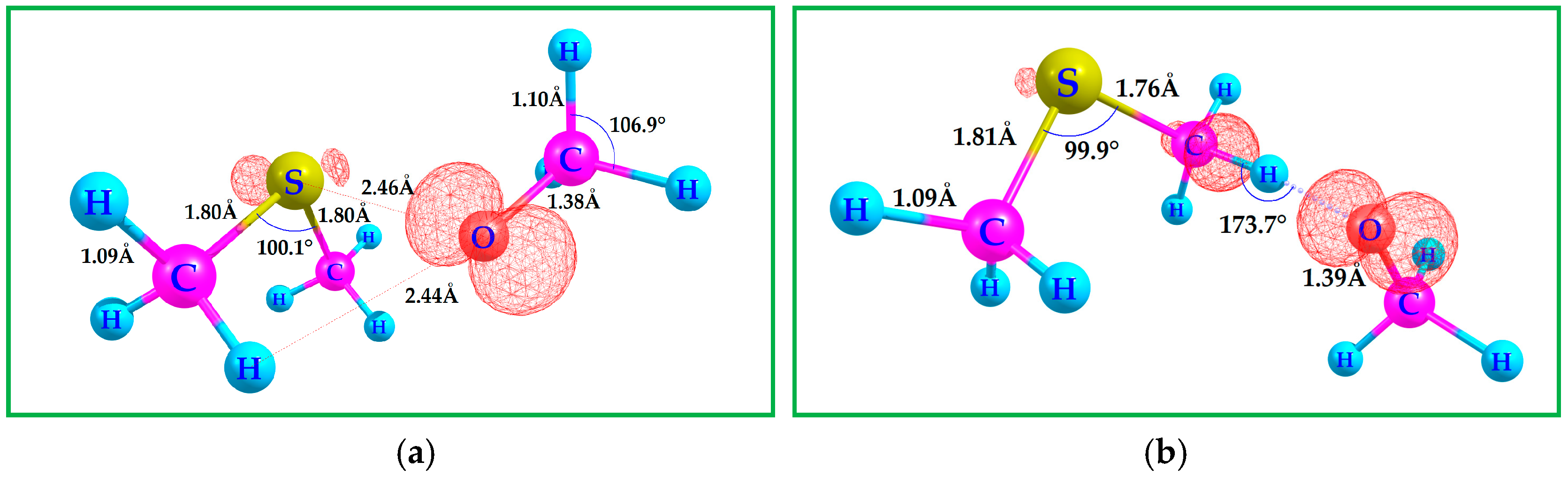

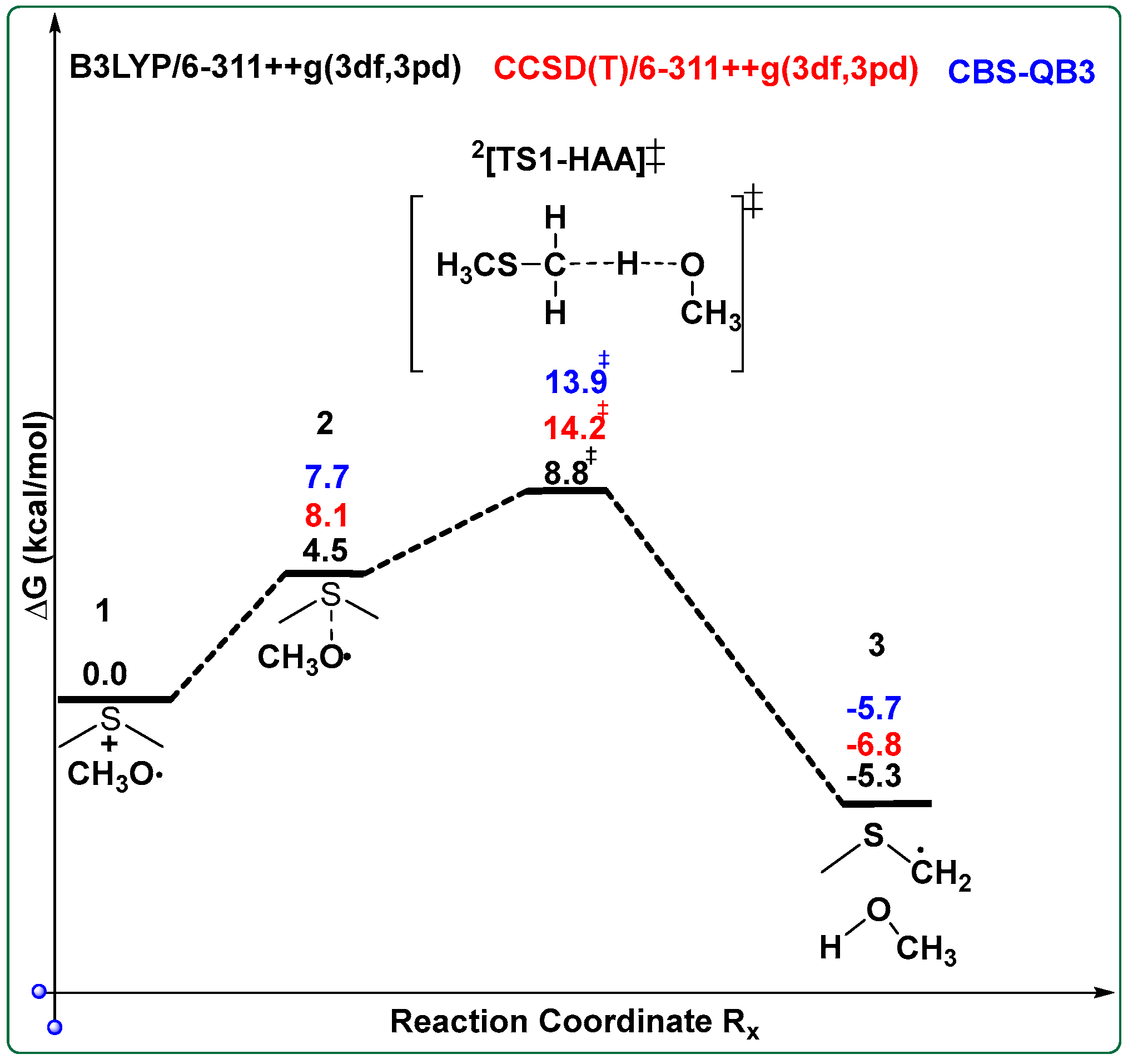

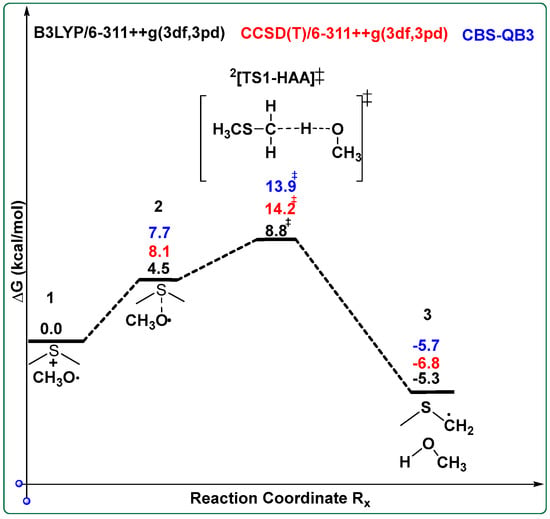

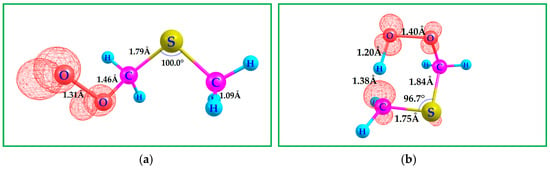

3.2. Binding DMS with CH3O•

The methoxy radical oxygen-atom is within 2.46 Å of the DMS sulfur atom, Figure 3: “a”. The optimized DMS with CH3O• C–H and C–O bond lengths are 1.09 and 1.38 Å, respectively, Figure 3: “a”, which is in line with the free molecules; however, the C–O bond length of the free CH3O• is 0.02 Å shorter at the current working level of theory, B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd). The computed Gibbs free energetics show that the binding of CH3O• to DMS is endergonic for the three methods utilized, Scheme 3, with respect to separated reactants. The optimized geometries of all species discussed in Scheme 3 are provided in the SI. The C–H activation energy of DMS by the CH3O• radical via HAA transition state [HAA-TS1]‡ clearly shows an early transition state with the moving hydrogen atom bond length of only 1.22 Å with an imaginary frequency of 865i cm−1, Figure 3: “b”. At the CCSD(T)/6-311++G(3df,3pd)//B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) level of theory, the DMS + CH3O• HAA reaction proceeds through a TS with a Gibbs free-energy barrier of 14.2 kcal/mol. This barrier is approximately 5 kcal/mol higher than that of the well-studied DMS + •OH pathway, for which previous work reports ΔG‡ values of 8–10 kcal/mol under similar conditions [20,58,59]. This comparison highlights that CH3O• initiated oxidation of DMS is less favorable than reaction with •OH, consistent with the significantly lower calculated rate coefficient (298.15 K and 1 atm).

Figure 3.

(a) Computed B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) geometries for the interaction of DMS with CH3O•. (b) Transition state geometry for C–H activation via HAA by CH3O•. Contour value of the spin density plot is 0.020 a.u.: Red = positive spin density. The transition state highlights the approach of CH3O• toward the DMS. Hydrogen and the redistribution of spin density, supporting the proposed reaction mechanism.

Scheme 3.

Potential energy diagram for the reaction DMS and the CH3O•, computed at three levels of theory: B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) (black), CCSD(T)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) (red), and CBS-QB3 (blue). The diagram illustrates the relative Gibbs free energies (ΔG and ΔG‡, in kcal/mol) of the reactants, transition state (‡), and products. Energies are referenced to the separated reactants and highlight consistency across methods in identifying the reaction barrier and exergonic nature of the hydrogen atom abstraction pathway.

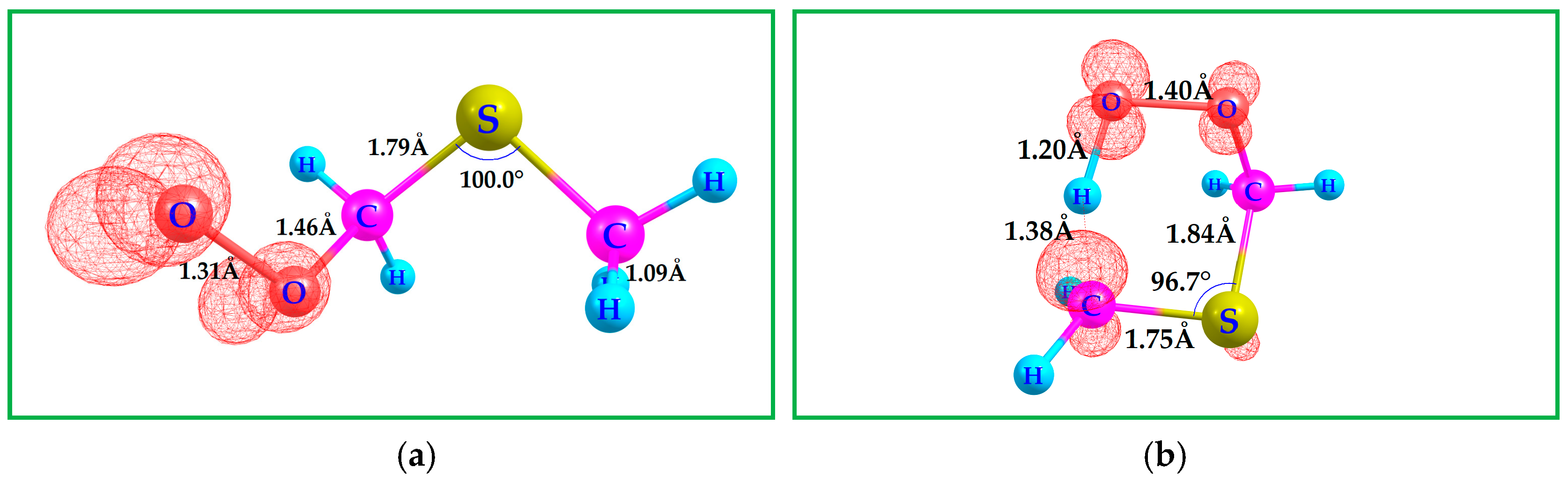

In the reaction pathway of DMS oxidation, CH3O• interacts with DMS through HAA, leading to the formation of the methylthiomethyl radical (MSM, CH3SCH2•). The MSM species then rapidly reacts with molecular oxygen to yield the methylthio-methoxy peroxy radical, CH3SCH2OO• (MTMP). Subsequent reactions of MTMP with atmospheric oxidants such as NO•, HO2, and RO2 govern its atmospheric fate and further oxidation [20,24,30,60]. This reaction highlights the importance of CH3O• as secondary oxidants that complement the established pathways involving HO• and NO• radicals. The Gibbs free-energy profiles reveal a higher activation barrier for the DMS + CH3O• pathway relative to the DMS + HO• pathway, consistent with its much smaller rate constant, Table 2.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters for key atmospheric reactions involving DMS and CH3O•. Rate coefficients were calculated at 298.15 K using canonical TST and zero-point–corrected activation energies (ΔE0‡). Tunneling corrections were not applied. Activation energies (ΔE0‡) are zero-point–corrected electronic barriers derived from CCSD(T)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) single-point energies.

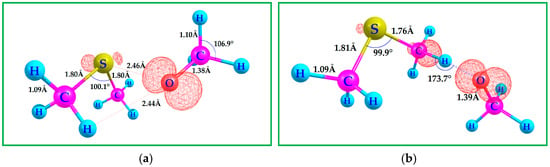

Although the CH3O• pathway is less efficient globally, its mechanistic characterization remains important because even slow, localized oxidation routes can seed secondary aerosol formation in methane-rich micro-environments. The Gibbs free energetics of MSM, CH3SCH2•, is exergonic for the three computational models utilized relative to separated reactants as shown in Scheme 3. Previous studies have reported similar mechanistic behavior and comparable barrier heights for alkoxy-radical–initiated HAA, and these investigations collectively support the trends observed here for the CH3O• initiated oxidation of DMS [61,62], Figure 4. Beyond the HAA reaction examined here, CH3O• may also react with DMS through S-centered addition pathways to form intermediates such as CH3S(OCH3)CH3 or CH3SOCH3 + •CH3. These pathways were not explored in the present study but represent important targets for future computational and experimental work aimed at developing a more complete mechanistic picture of CH3O• initiated DMS oxidation. While sulfate aerosols formed through the oxidation of DMS by CH3O• may play a role in cloud formation and radiative forcing, further studies are required to quantify their significance as CCN and to fully understand their broader impacts on atmospheric processes.

Figure 4.

(a) Computed B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) geometries of the MTMP radical. (b) Transition state geometry for the intramolecular H-shift within (MTMP‡). Contour value of the spin density plot is 0.020 a.u.: Red = positive spin density. The transition state highlights the hydrogen transfer between adjacent carbon atom and oxygen atom, a key step in the atmospheric processing of sulfur-containing peroxy radicals.

4. Kinetics of DMS with CH3O•

The computed rate constants for the oxidation of DMS reveal significant differences in reactivity between •OH and CH3O•. The calculated rate constant for the reaction of DMS with •OH is 4.34 × 10−12 cm3/molecule/s, which aligns well with literature values of 4.22 × 10−12 (±0.07) cm3/molecule/s by Williams et al. [58,59,60,63]. In contrast, the rate constant for the reaction with CH3O• is significantly lower by over four orders of magnitude, calculated at 3.05 × 10−16 cm3/molecule/s. Additionally, the reaction of CH3O• with O2 to form formaldehyde (CH2O) and hydroperoxyl radicals (HO2•) proceeds with a relatively low-rate constant of 5.51 × 10−17 cm3/molecule/s, consistent with previous literature values, indicating slow kinetics under typical atmospheric conditions in the absence of catalysis. However, a study by Mallick et al. demonstrated that the presence of a single water molecule significantly lowers the reaction barrier, from 3.01 kcal/mol to −1.86 kcal/mol, enhancing the rate constant by four to five orders of magnitude [64]. This suggests that under humid conditions, CH3O• may be more reactive than previously considered, emphasizing the need to account for water-mediated pathways in atmospheric modeling. The thermal energy barriers for these reactions further emphasize their distinctions: 0.3 kcal/mol for DMS with •OH, 5.3 kcal/mol for DMS with CH3O•, and 4.4 kcal/mol for CH3O• with O2, outlined in Table 2. Thus, while thermochemical profiles initially suggested comparable exergonicity of products, the transition-state energetics confirm that the CH3O• pathway proceeds much more slowly. Activation energies reported in Table 2 represent zero-point corrected electronic barriers (ΔE0‡) computed at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) level of theory. Activation free energies (ΔG‡), which include thermal and entropic corrections, are shown in Scheme 3 and may differ from ΔE0‡ due to these contributions as well as higher-level single-point energy refinements.

Table 2 summarizes the key transition state (TS) energetics and kinetic rate constants (k) of the reaction pathways involving •OH and CH3O• in the atmospheric oxidation of DMS and methoxy radical’s interaction with O2. The table highlights activation energy barriers (ΔE‡), computed rate constants, and the relative importance of each reaction. While •OH driven oxidation of DMS dominates globally, CH3O• driven pathways may hold localized significance in methane-rich environments, and at the same time CH3O• is rapidly removed through its reaction with O2 as predicted consistently across all levels of theory B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-311++G(3df,3pd), CCSD(T)/6-311++G(3df,3pd) and CBS-QB3; black, red, and blue, respectively. Details of these calculations are provided in the SI.

These findings reveal that the reactivity hierarchy is governed by the intrinsic properties of radicals. The hydroxyl radical, being a highly reactive species with minimal steric hindrance, rapidly abstracts hydrogen atoms. In contrast, the methoxy radical, stabilized by its electron-withdrawing oxygen atom, exhibits reduced hydrogen abstraction efficiency, especially when reacting with DMS or O2. When CH3O• reacts with O2, it forms intermediates like formaldehyde and hydroperoxyl radicals, which are pivotal in SOA formation.

The structural characteristics of DMS amplify these differences. DMS contains relatively accessible C-H bonds, allowing •OHs to interact with minimal steric or electronic interference. In contrast, the steric and electronic effects of DMS hinder the reaction with CH3O•, leading to significantly slower reaction rates. Quantitatively, the reaction of DMS with •OH is approximately 14,230 times faster than that with CH3O•, and the CH3O• with O2 reaction rate is about 12.8 times slower than DMS with CH3O•, underscoring the limited but potentially significant role of CH3O• in localized sulfur cycling.

While globally the contribution of CH3O• radicals to DMS oxidation may be limited due to their low steady-state concentrations and shorter atmospheric lifetimes, their localized role in specific environments cannot be overlooked [14,65]. Methane-rich zones such as wetlands, regions of methane seeps, or areas influenced by anthropogenic emissions provide a fertile ground for CH3O• generation through methane oxidation [13,16]. When these regions overlap with DMS producing marine environments, such as those rich in phytoplankton activity [65]. CH3O• radicals may act as secondary oxidants complementing the primary role of •OH [16].

In such localized microenvironments, the CH3O• driven pathway may influence the production of SO2 and intermediate sulfur-containing compounds like methyl-thiomethylene radicals (CH3SCH2•). These intermediates can further propagate oxidation chains, producing hydroperoxyl radicals (HOO•) and contributing to secondary organic aerosol (SOA) formation. Although CH3O• driven oxidation rates are slower than •OH driven reactions, their impact in methane- and DMS-rich zones warrants attention for their potential contribution to localized sulfur cycling and climate modulation. Integrating these pathways into regional atmospheric models could enhance their ability to predict localized variations in sulfur aerosol formation and its downstream effects on cloud dynamics and radiative forcing. Tunneling corrections were not included; for hydrogen-transfer reactions such as DMS + •OH, inclusion of Eckart tunneling typically lowers barriers by ≤1 kcal/mol and would not alter the qualitative trends reported here [51,66].

Atmospheric Implications

The high reactivity of •OHs reinforces their dominant role in atmospheric oxidation processes, particularly in the rapid conversion of sulfur-containing compounds like DMS into SO2 and sulfate aerosols. These products are central to CCN formation, which regulates cloud properties and radiative forcing. The slower reactivity of CH3O•, especially with O2, suggests that CH3O• contribute to atmospheric sulfur cycling only in specific methane- and DMS-rich environments, such as marine regions. This comprehensive analysis highlights the necessity of incorporating these reaction pathways into global climate models. The dominant role of •OH radicals in oxidizing DMS is reaffirmed by the much lower calculated barrier and faster kinetics.

The slower CH3O• reactions indicate that methoxy radicals contribute only marginally to sulfur cycling except where both methane and DMS emissions coincide—such as coastal or wetland boundary layers. Because CH3O• has a millisecond-scale lifetime and reacts preferentially with O2, its probability of encountering DMS is small; nevertheless, under locally elevated methane and humidity, transient CH3O• formation may still promote limited sulfur oxidation.

5. Summary

This study provides a detailed computational investigation into the kinetics and mechanisms of the oxidation of DMS by CH3O• under atmospheric conditions. The computational results show that the DMS + CH3O• reaction proceeds through a hydrogen-abstraction barrier 5 kcal/mol higher than the DMS + •OH pathway, giving a rate constant about 2 × 104 times smaller. The rapid removal of CH3O• by molecular oxygen (O2) further underscores its potential importance in specific atmospheric microenvironments. The results emphasize the need to explore alternative oxidation pathways to refine models of sulfur cycling, aerosol-cloud interactions, and radiative forcing. Future experimental validation of these findings, along with their integration into advanced atmospheric models, will improve our understanding of methane and sulfur emissions’ contributions to complex atmospheric processes.

6. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive investigation into the kinetics and mechanisms of CH3O• driven oxidation of DMS in the atmosphere. Computational analyses reveal that while the reaction of DMS and CH3O• has a slower rate constant (3.05 × 10−16 cm3/molecule/s) compared with the dominant hydroxyl radical •OH driven pathway, could hold localized significance in methane-rich environments such as marine boundary layers [14,51,67]. The reaction produces sulfur-containing intermediates that contribute to the atmospheric sulfur cycle and the formation of sulfate aerosols, which influences CCN formation. Additionally, the competitive reaction of CH3O• with molecular oxygen, characterized by a lower rate constant (5.51 × 10−17 cm3/molecule/s), highlights the rapid removal of CH3O• from the atmosphere. This further underscore the localized nature of its role in sulfur cycling. The energy barriers and rate constants computed in this study provide critical data for understanding the unique contributions of CH3O• to atmospheric chemistry. These findings emphasize the importance of exploring alternate oxidation pathways beyond those dominated by hydroxyl radicals. Incorporating CH3O• driven reactions into atmospheric models can refine predictions of sulfur cycling, aerosol-cloud interactions, and their broader impacts at local and regional scales. Future work should focus on experimental validation of these computational results and their integration into advanced climate models to improve predictions of methane and sulfur emissions on atmospheric processes. To support the computational findings, future experimental studies could investigate the reactivity of methoxy radicals with DMS using laboratory-based atmospheric simulation chambers or flow-tube reactors under controlled conditions. Detection of reaction intermediates such as CH3SCH2• (MSM) and SO2 could be achieved via laser-induced fluorescence (LIF), cavity ring-down spectroscopy (CRDS), or mass spectrometry. Additionally, leveraging regional air quality monitoring networks, such as collocated SO2 and CH4 data from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) in the Houston metropolitan area, may provide indirect observational evidence for DMS oxidation under CH4-rich atmospheric conditions. These efforts would help validate the proposed CH3O• driven oxidation pathway and refine its role in atmospheric sulfur cycling. Overall, CH3O• should be viewed as a secondary, locally active oxidant rather than a globally dominant pathway, which is an interpretation fully consistent with the computed Gibbs free energies and rate coefficients.

7. Prospectus

This study advances our understanding of the role of CH3O• in atmospheric chemistry, particularly in the localized oxidation of DMS. While the global impact of CH3O• driven reactions is limited due to their low steady-state concentrations and rapid removal by molecular oxygen, this pathway may play a significant role in methane-rich environments, such as coastal urban boundary layers where DMS emissions overlap with methane oxidation processes. The kinetic and thermodynamic data provided herein serve as a foundation for future research on alternative oxidation mechanisms that are not dominated by hydroxyl radicals. The identification of energy barriers and reaction rates under atmospheric conditions opens avenues for exploring additional localized processes that influence sulfur cycling, aerosol formation, and climate regulation. We encourage the following studies to be performed in the future:

- Experimental Validation: Laboratory investigations of the CH3O• with DMS reaction are essential to confirm the computational findings and quantify reaction products.

- Environmental Relevance: Field measurements in coastal urban boundary layers and other methane-rich environments could assess the real-world significance of CH3O• driven sulfur oxidation.

- Integration into Models: Incorporating CH3O• driven pathways into local and regional atmospheric models would refine predictions of aerosol-cloud interactions, improving our understanding of their impact on CCN and radiative forcing. By addressing these areas, the broader role of CH3O• in atmospheric chemistry can be elucidated, enabling more accurate predictions of methane and sulfur emissions’ contributions to climate dynamics. This work underscores the importance of integrating computational and experimental approaches to uncover the complexities of atmospheric processes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://zenodo.org/records/16375956 (accessed on 13 November 2025), The Cartesian coordinates of all calculated species, along with their spin multiplicities and full citation details, are provided.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.M.P.; Methodology, B.M.P.; Validation, B.M.P., M.C.H., D.V., M.P.J., M.Z. and C.K.; Formal analysis, B.M.P., M.P.J. and M.Z.; Investigation, B.M.P., D.V. and C.K.; Writing—original draft, B.M.P.; Writing—review and editing, B.M.P., M.C.H., D.V., M.P.J., M.Z. and C.K.; Visualization, B.M.P., M.C.H., D.V., M.P.J., M.Z. and C.K.; Funding acquisition, B.M.P., M.C.H., D.V., M.P.J., M.Z. and C.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by Texas Southern University (TSU) High Performance Computing Center and U.S. Department of Energy grants DE-FOA-0002688 and DE-FOA-0002929.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DMS | dimethyl sulfide |

| CCN | cloud condensation nuclei |

| HAA | hydrogen atom abstraction |

| OAT | oxygen atom transfer |

| MSM | methyl-thiomethylene |

| DFT | density functional theory |

| PES | potential energy surface |

References

- Letters to the Editor: Methane. Chemical & Engineering News. Available online: https://cen.acs.org/energy/hydrogen-power/Reactions/100/i2 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Methane Cuts Could Slow Extreme Climate Change. Chemical & Engineering News. Available online: https://cen.acs.org/environment/climate-change/Methane-cuts-slow-extreme-climate-change/99/i39 (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Glass, R.S. Sulfur Radicals and Their Application. Top. Curr. Chem. 2018, 376, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, Y. Mechanistic and dynamic investigations for multi-channel reaction of CH3O2 + NO. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM 2005, 725, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesar, A.; Hodošček, M.; Drougas, E.; Kosmas, A.M. Quantum Mechanical Investigation of the Atmospheric Reaction CH3O2 + NO. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 7898–7903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, R.J.; Lovelock, J.E.; Andreae, M.O.; Warren, S.G. Oceanic phytoplankton, atmospheric sulphur, cloud albedo and climate. Nature 1987, 326, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomans, B.P.; den Camp, H.J.M.; Pol, A.; Vogels, G.D. Anaerobic versus aerobic degradation of dimethyl sulfide and methanethiol in anoxic freshwater sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiene, R.P. Production of methanethiol from dimethylsulfoniopropionate in marine surface waters. Mar. Chem. 1996, 54, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreae, M.O.; Crutzen, P.J. Atmospheric Aerosols: Biogeochemical Sources and Role in Atmospheric Chemistry. Science 1997, 276, 1052–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardine, K.; Yañez-Serrano, A.M.; Williams, J.; Kunert, N.; Jardine, A.; Taylor, T.; Abrell, L.; Artaxo, P.; Guenther, A.; Hewitt, C.N.; et al. Dimethyl sulfide in the Amazon rain forest. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2015, 29, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, G.P.; Cainey, J.M. The CLAW hypothesis: A review of the major developments. Environ. Chem. 2007, 4, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, D.D.; Prinn, R.G. Mechanistic studies of dimethylsulfide oxidation products using an observationally constrained model. J. Geophys. Res. D Atmos. 2002, 107, ACH 12-1–ACH 12-26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linke, P.; Sommer, S.; Rovelli, L.; McGinnis, D.F. Physical limitations of dissolved methane fluxes: The role of bottom-boundary layer processes. Mar. Geol. 2010, 272, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alligood, B.W.; FitzPatrick, B.L.; Glassman, E.J.; Butler, L.J.; Lau, K. Dissociation dynamics of the methylsulfonyl radical and its photolytic precursor CH3SO2Cl. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 131, 044305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Blomquist, B.W.; Huebert, B.J. Constraining the concentration of the hydroxyl radical in a stratocumulus-topped marine boundary layer from sea-to-air eddy covariance flux measurements of dimethylsulfide. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009, 9, 9225–9236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, G.A.; Kilgour, D.B.; Jernigan, C.M.; Vermeuel, M.P.; Bertram, T.H. Oceanic emissions of dimethyl sulfide and methanethiol and their contribution to sulfur dioxide production in the marine atmosphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 6309–6325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourzac, K. The other important greenhouse gas. C&EN Glob. Enterp. 2021, 99, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lee, H.; Jin, P. Significance of anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) in mitigating methane emission from major natural and anthropogenic sources: A review of AOM rates in recent publications. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2022, 1, 401–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, B.M.; Cundari, T.R. C-H Bond Activation of Methane by PtII-N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes. The Importance of Having the Ligands in the Right Place at the Right Time. Organometallics 2012, 31, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, I.; Hjorth, J.; Mihalopoulos, N. Dimethyl Sulfide and Dimethyl Sulfoxide and Their Oxidation in the Atmosphere. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 940–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seinfeld, J.H.; Pandis, S.N. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Long, B.; Bao, J.L.; Truhlar, D.G. Kinetics of the Strongly Correlated CH3O + O2 Reaction: The Importance of Quadruple Excitations in Atmospheric and Combustion Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, J.J.; Tyndall, G.S.; Wallington, T.J. The Atmospheric Chemistry of Alkoxy Radicals. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 4657–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R. Rate constants for the atmospheric reactions of alkoxy radicals: An updated estimation method. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 8468–8485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, S.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, P. Revisiting the reaction energetics of the CH3O• + O2 (3Σ−) reaction: The crucial role of post-CCSD(T) corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. PCCP 2019, 21, 6559–6565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, R.L.; Gao, S. 3.01—Composition of the Continental Crust. In Treatise on Geochemistry; Holland, H.D., Turekian, K.K., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Dibble, T.S.; Chai, J. Critical Review of Atmospheric Chemistry of Alkoxy Radicals. In Advances in Atmospheric Chemistry; Critical Review of Atmospheric Chemistry of Alkoxy Radicals; World Scientific: Singapore, 2016; pp. 185–269. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Dibble, T.S. Quantum Chemistry, Reaction Kinetics, and Tunneling Effects in the Reaction of Methoxy Radicals with O2. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 14230–14242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson, R.E.; Cicerone, R.J. Future global warming from atmospheric trace gases. Nature 1986, 319, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueyama, M.; Fujimoto, A.; Ito, A.; Takahashi, Y.; Ide, R. Constraining models for methane oxidation based on long-term continuous chamber measurements in a temperate forest soil. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 310, 108654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunois, M.; Stavert, A.R.; Poulter, B.; Bousquet, P.; Canadell, J.G.; Jackson, R.B.; Raymond, P.A.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Houweling, S.; Patra, P.K.; et al. The Global Methane Budget 2000–2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 1561–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackels, C.F. A potential-energy surface study of the 2A1 and low-lying dissociative states of the methoxy radical. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Correlation energy of an inhomogeneous electron gas: A coordinate-space model. J. Chem. Phys. 1988, 88, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard, P. Statistical mechanical theory for steady state systems. II. Reciprocal relations and the second entropy. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 122, 154101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, R.; Binkley, J.S.; Seeger, R.; Pople, J.A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crittenden, D.L. A Systematic CCSD(T) Study of Long-Range and Noncovalent Interactions between Benzene and a Series of First- and Second-Row Hydrides and Rare Gas Atoms. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurecka, P.; Sponer, J.; Cerny, J.; Hobza, P. Benchmark database of accurate (MP2 and CCSD(T) complete basis set limit) interaction energies of small model complexes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, A.D.; Chandler, G.S. Contracted Gaussian basis sets for molecular calculations. I. Second row atoms, Z=11–18. J.Chem.Phys. 1980, 72, 5639–5648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J.A., Jr.; Frisch, M.J.; Ochterski, J.W.; Petersson, G.A. A complete basis set model chemistry. VI. Use of density functional geometries and frequencies. J.Chem.Phys. 1999, 110, 2822–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, E.; Moreno, M.; Lluch, J.M.; Bertrán, J. Intrinsic reaction coordinate calculations for reaction paths possessing branching points. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1989, 160, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.W.; Gordon, M.S.; Dupuis, M. The intrinsic reaction coordinate and the rotational barrier in silaethylene. J.Am.Chem.Soc. 1985, 107, 2585–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, T.; Reid, P. Thermodynamics, Statistical Thermodynamics and Kinetics, 4th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2019; pp. 526–530. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, J.A., Jr.; Frisch, M.J.; Ochterski, J.W.; Petersson, G.A. A complete basis set model chemistry. VII. Use of the minimum population localization method. J.Chem.Phys. 2000, 112, 6532–6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R.; Baulch, D.L.; Cox, R.A.; Hampson, R.F.; Kerr, J.A.; Rossi, M.J.; Troe, J. Evaluated Kinetic and Photochemical Data for Atmospheric Chemistry: Supplement VI. IUPAC Subcommittee on Gas Kinetic Data Evaluation for Atmospheric Chemistry. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1997, 26, 1329–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walch, S.P.; Dunning, T.H., Jr. Calculated barrier to hydrogen atom abstraction from CH4 by O(3P). J.Chem.Phys. 1980, 72, 3221–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleimanov, Y.V.; Espinosa-Garcia, J. Recrossing and Tunneling in the Kinetics Study of the OH + CH4 → H2O + CH3 Reaction. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 1418–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azbar, N.; Yonar, T.; Kestioglu, K. Comparison of various advanced oxidation processes and chemical treatment methods for COD and color removal from a polyester and acetate fiber dyeing effluent. Chemosphere 2004, 55, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, L. Kinetic study of hydroxyl radical formation in a continuous hydroxyl generation system. RSC advances 2018, 8, 4632–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdge, J. Chapter 19 Electrochemistry. In Chemistry; McGraw Hill, 2023; p. 970. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, A.M.; Agarwal, J.; Schaefer, H.F.; Douberly, G.E. Infrared laser spectroscopy of the CH3OO radical formed from the reaction of CH3 and O2 within a helium nanodroplet. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 5299–5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Huang, C.; Xie, B.; Wu, X. Revisiting the chemical kinetics of CH3 + O2 and its impact on methane ignition. Combust. Flame 2019, 200, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stimac, P.J.; Barker, J.R. Non-RRKM Dynamics in the CH3O2 + NO Reaction System. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 2553–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.B.; Campuzano-Jost, P.; Hynes, A.J.; Pounds, A.J. Experimental and Theoretical Studies of the Reaction of the OH Radical with Alkyl Sulfides: 3. Kinetics and Mechanism of the OH Initiated Oxidation of Dimethyl, Dipropyl, and Dibutyl Sulfides: Reactivity Trends in the Alkyl Sulfides and Development of a Predictive Expression for the Reaction of OH with DMS. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 6697–6709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salta, Z.; Lupi, J.; Barone, V.; Ventura, O.N. H-Abstraction from Dimethyl Sulfide in the Presence of an Excess of Hydroxyl Radicals. A Quantum Chemical Evaluation of Thermochemical and Kinetic Parameters Unveils an Alternative Pathway to Dimethyl Sulfoxide. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2020, 4, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R.; Baulch, D.L.; Cox, R.A.; Crowley, J.N.; Hampson, R.F.; Hynes, R.G.; Jenkin, M.E.; Rossi, M.J.; Troe, J. Evaluated kinetic and photochemical data for atmospheric chemistry: Volume I—Gas phase reactions of Ox, HOx, NOx and SOx species. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2004, 4, 1461–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R. Gas-Phase Tropospheric Chemistry of Volatile Organic Compounds: 1. Alkanes and Alkenes. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1997, 26, 215–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michoud, V.; Kukui, A.; Camredon, M.; Colomb, A.; Borbon, A.; Miet, K.; Aumont, B.; Beekmann, M.; Durand-Jolibois, R.; Perrier, S.; et al. Radical budget analysis in a suburban European site during the MEGAPOLI summer field campaign. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 11951–11974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, A.J.; Wine, P.H.; Semmes, D.H. Kinetics and mechanism of hydroxyl reactions with organic sulfides. J. Phys. Chem. 1986, 90, 4148–4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, S.; Kumar, A.; Mishra, B.K.; Kumar, P. Influence of water on the CH3O• + O2 → CH2O + HO2· reaction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. PCCP 2019, 21, 15734–15741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardyukov, A.; Schreiner, P.R. Atmospherically Relevant Radicals Derived from the Oxidation of Dimethyl Sulfide. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truhlar, D.G.; Garrett, B.C.; Klippenstein, S.J. Current Status of Transition-State Theory. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 12771–12800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicovich, J.M.; Parthasarathy, S.; Pope, F.D.; Pegus, A.T.; McKee, M.L.; Wine, P.H. Kinetics, Mechanism, and Thermochemistry of the Gas Phase Reaction of Atomic Chlorine with Dimethyl Sulfoxide. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 6874–6885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.