Abstract

Background: Burnout, a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced personal accomplishment, is a significant concern among dental students because of the intense demands of their academic and clinical training. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of burnout and its related dimensions among dental students at King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted among 300 dental students (147 males, 153 females) from the 4th year to the internship level, selected via simple random sampling. A 12-item survey called the Burnout Clinical Subtype Questionnaire-12-Student Survey (BCSQ-12-SS) was validated for use with students. Burnout was assessed across three domains—Overload, Lack of Development, and Neglect. Descriptive statistics, Mann–Whitney U tests, and Kruskal–Wallis analyses were employed to explore gender- and year-based differences. Results: Overload and Lack of Development were the most prominent burnout dimensions, with more than half of participants reporting excessive academic pressure, personal sacrifices, and dissatisfaction with developmental opportunities. Neglect demonstrated the lowest prevalence. Female students exhibited significantly higher total burnout scores (p = 0.005). Burnout varied across academic years, peaking among fourth-year students (p < 0.001). Internal consistency for all domains was acceptable to excellent (α = 0.62–0.89). Conclusions: Burnout is highly prevalent, particularly in the domains of Overload and Lack of Development. Female and mid-program students represent high-risk groups. Institutional reforms, curricular enhancement, workload redistribution, structured support systems, and early mental-health interventions are crucial to mitigate burnout and promote student well-being.

1. Introduction

Burnout, characterized by emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced personal accomplishment, represents a significant occupational hazard, particularly in demanding academic and professional fields such as dentistry [1]. This phenomenon is increasingly recognized among dental students owing to the unique stressors associated with rigorous academic curricula, demanding clinical training, and patient care responsibilities [2,3]. These pressures can culminate in a state of chronic stress, negatively impacting students’ psychological well-being, academic performance, and future professional efficacy [4,5]. Understanding the prevalence and contributing factors of burnout among dental students is crucial for developing targeted interventions to mitigate its adverse effects and foster a healthier academic and professional environment [1]. This research utilizes the BCSQ-12-SS to move beyond general stress and categorize burnout into specific clinical subtypes (Overload, Lack of Development, Neglect), allowing for more precise psychiatric screening in high-pressure medical environments. Burnout is defined as a psychological syndrome characterized by the presence of discouraging emotions, including emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (cynicism), and low personal efficacy (reduced personal accomplishment) [6]. It is an adverse and persistent mental state that arises from chronic interpersonal tensions in role-based settings, including but not limited to professional, academic, and caregiving environments, with the present study focusing on academic and clinical training contexts among dental students. In clinical educational contexts such as dentistry, burnout manifests as physical and emotional exhaustion arising from the cumulative demands of academic study, clinical training, and patient care responsibilities [6]. Burnout is characterized by emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced personal accomplishment. Among dental students, prevalence rates vary considerably worldwide, ranging from 13% to over 70%, depending on measurement tools, cultural context, and academic pressures. [7,8]. Students in demanding fields, such as dentistry, face a multitude of stressors beyond rigorous academic workloads and intensive clinical training. These include managing patient care responsibilities, financial obligations, societal demands, high expectations, and the pervasive dread of failure [9]. Environmental factors such as inadequate study spaces and insufficient rest, along with interpersonal challenges arising from difficulties in establishing relationships due to short rotations and integration into healthcare teams, further contribute to this stress. Individual predispositions, including anxiety, depressive symptoms, lack of motivation, low resilience, and a marked tendency toward perfectionism, also significantly increase the risk of burnout [8]. Furthermore, the demanding nature of postgraduate dental programs, coupled with the socio-cultural adjustment challenges faced by international students, exacerbates these pre-existing stressors, leading to elevated rates of stress and burnout [1]. The World Health Organization formally recognizes burnout as a syndrome stemming from unmanaged chronic workplace stress, encompassing emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment [10].

The pervasive issue of burnout among dental students warrants further elaboration given its complex etiology and profound consequences. Beyond the inherent demands of dental education, several specific factors exacerbate stress and contribute to burnout. These include a challenging learning environment characterized by insufficient faculty and staff support, exposure to cynical senior colleagues, scarcity of supportive resources, and inadequate time off. Grading schemes, where letter grading systems are associated with higher rates of burnout, intensify the pressure compared with pass/fail systems [11]. Individual student characteristics, such as perfectionism, low academic self-efficacy, and a history of negative personal life events (such as family illness, bereavement, financial difficulties, or relationship instability) further elevate risk. The demanding nature of dental programs often leads students to invest an unhealthy amount of effort into their studies, neglecting personal life and even endangering their health in pursuit of academic success [9,12]. This overload, coupled with insecurity about one’s chosen career path, can manifest as a negative attitude and feelings of incompetence. Studies show that first-year students often experience high stress when adapting to a new, competitive environment and managing a heavy workload, while even senior students nearing graduation may face anxieties about skill deficiencies and meet high expectations [12].

The consequences of burnout can extend beyond academic performance. It is a significant predictor of various mental health issues, including anxiety and depressive disorders [12], and can severely impair academic success, interpersonal relationships, and future career prospects. Medical and dental students exhibit a higher propensity for mental health challenges than the general population [3], with a notable prevalence of burnout components [3]. Recognizing this, international efforts have highlighted the critical need for early identification and preventive strategies to safeguard students’ psychological well-being [12]. This includes fostering accessible support systems, normalizing discussions around mental health in academic settings, and providing training in self-care techniques to equip students with resilience for their demanding careers [13]. For instance, a study in Cuba reported a burnout prevalence of 34.8% among dental students [14], a value that falls within the mid-range globally when compared with Middle Eastern prevalence (40–60%), European rates (20–45%), and Asian cohorts (25–55%). This highlights the importance of contextualizing burnout findings across diverse educational systems [6,10,14].

Therefore, a deeper understanding of the prevalence of burnout and the intricate web of contributing factors among dental students is not merely academic. It is essential to develop effective interventions that promote a healthier, more supportive educational environment and ensure the long-term well-being of future dental professionals. The impact of burnout on students can be severe, detrimentally affecting their academic development and overall well-being [9,15]. It can impair academic performance and has been identified as a significant independent predictor of suicidal ideation and students dropping out of their programs [9]. Therefore, understanding and addressing burnout among dental students is crucial to their mental health and academic success. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of burnout among dental students at the King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia.

2. Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted to determine the prevalence of burnout among dental students at the College of Dentistry, King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia.

2.1. Participants

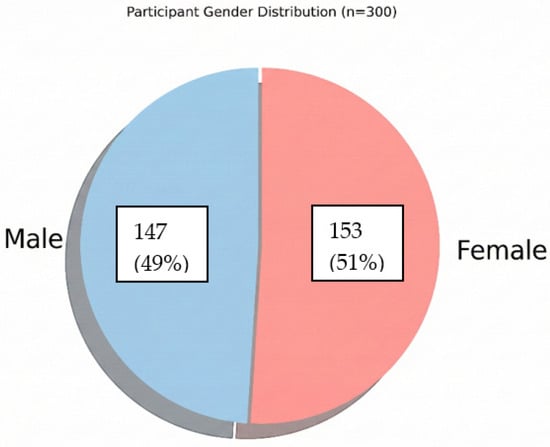

This study included 300 dental students, including 147 males and 153 females. A total of 350 students were invited; 300 completed the survey (response rate 85.7%). The participants’ ages ranged from 20 to 35 years old. To select the participants, the researchers employed a simple random sampling method, ensuring that every student in the target population had an equal and independent chance of being included in the study. This method was selected to broaden the applicability of the results to the entire population of university dental students.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

Prior to the commencement of the study, formal ethical approval was secured from the Scientific Research Committee of the College of Dentistry at King Khalid University [IRB/KKU/COD/ETH/2023-24/040]. The purpose and procedures of the study were thoroughly explained to all participants. Subsequently, written informed consent was obtained from all the students who agreed to participate, guaranteeing voluntary and informed involvement. The confidentiality and anonymity of the participants were maintained throughout the research process.

2.3. Study Design and Procedure (Instrument Used)

Data were collected using a structured self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed and disseminated electronically through online Google Forms, providing a convenient and efficient method for reaching students.

The questionnaire was divided into two main sections: demographic information, which gathered basic data on participants’ age, sex, and academic year, and a twelve-item burnout assessment. Burnout was assessed using the 12-item Burnout Clinical Subtypes Questionnaire adapted for students, comprising three dimensions: Overload (Q1–Q4), Lack of Development (Q5–Q8), and Neglect (Q9–Q12). By employing this specific framework, the study moves beyond measuring general stress to provide a structured clinical categorization suitable for psychiatric screening. Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). Internal consistency reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha [16]. Prior to its final deployment, the questionnaire underwent stringent validation to ascertain its reliability and suitability for the intended demographics. A preliminary validation phase was conducted to confirm the efficacy of the instrument in assessing burnout among dental students at King Khalid University. Before full implementation, the self-administered questionnaire was initially pilot tested with a convenience sample of 20 dental students. This pilot test aimed to gather feedback on the length of the questionnaire and clarity of its language. Based on the students’ input, the necessary adjustments and corrections were made to enhance the instrument’s comprehensibility and acceptability. Furthermore, the content validity of the questionnaire was assessed before the research officially commenced, ensuring that the items accurately and comprehensively covered the intended dimensions of burnout that were relevant to dental students.

For broader context and to strengthen the methodological foundation, it is important to note that the 12-item inventory used in this study is based on a previously established framework that aligns with instruments like the Burnout Clinical Subtype Questionnaire-12-Student Survey (BCSQ-12-SS) [9,12]. This type of questionnaire, designed to assess overload, lack of development, and neglect, has undergone rigorous psychometric evaluation in various populations of dental students. For instance, a study conducted in the United Arab Emirates evaluated the internal consistency of the BCSQ-12-SS using Cronbach’s alpha. The results showed acceptable reliability for the ‘lack of development’ domain (alpha = 0.79) and total burnout (alpha = 0.71), while the ‘neglect’ domain showed marginal reliability (alpha = 0.62) [12]. Another study evaluating the psychometric properties of the BCSQ-12-SS in Iranian dental students confirmed its construct, convergent, and divergent validity through methods such as Exploratory Factor Analysis and Confirmatory Factor Analysis, with content validity values exceeding 0.7 [17]. Similarly, the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey, a widely recognized burnout assessment tool, has also been translated and validated for use among Saudi dental students, with studies examining its psychometric properties and factorial structure [18]. The initial pilot testing and content validation performed in this study are crucial first steps, building upon the established reliability and validity of similar conceptual frameworks used in global burnout research [16,17,18].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including mean and standard deviation, were calculated. Cronbach coefficients were calculated to assess the internal reliability of each domain of the questionnaire. Mean scores were calculated for each burnout dimension. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to examine gender differences, while the Kruskal–Wallis tests assessed differences across academic years. Significance level set at p ≤ 0.05. SPSS software (version 20.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the statistical analysis, with a significance level of p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

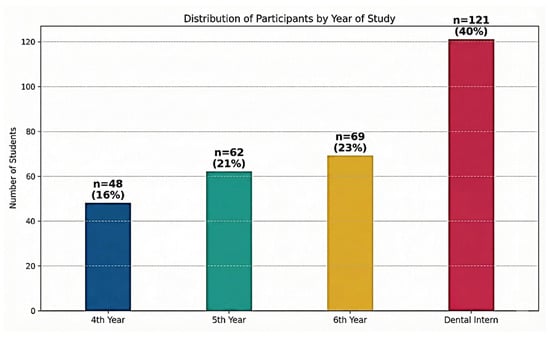

Of the 300 dental students who participated in the study, there was a nearly even distribution of sex. Females constituted a small majority (51%, n = 153), while males comprised 49% (n = 147) of the sample (Figure 1). When distributed by academic level, the largest group of respondents was Dental Interns, who made up 40% (n = 121) of the participants. They were followed by 6th-year students at 23% (n = 69) and 5th-year students at 21% (n = 62). The smallest group represented in the study was the 4th-year students, who accounted for 16% (n = 48) of the total sample (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Distribution of participants according to gender.

Figure 2.

Distribution of participants according to year of study.

3.2. Descriptive Statistics of the Variables Under Study

The overload dimension showed the highest prevalence of burnout indicators. A significant majority of students expressed feelings of being overwhelmed by their academic commitment. For instance, 58% of participants either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, “I think I invest more than is healthy in my commitment to my studies” (Q1). Similarly, 53% of students felt that they were neglecting their personal life (Q2), endangering their health (Q3), and ignoring their own needs (Q4) to satisfy the requirements of their studies (Table 1). This suggests that a substantial portion of the student body experiences high levels of academic pressure, leading to personal sacrifices. In the domain of lack of development, more than half of the students expressed dissatisfaction with their personal and professional growth in the curriculum. The highest level of agreement was for Q5, where 57% indicated they “would like to study something else that would be more challenging.” Furthermore, 51% felt that their current studies were “hampering the development of my abilities” (Q6) and that they could “better develop my talent” elsewhere (Q7). However, fewer students (47%) felt that their studies did not provide opportunities for development (Q8), indicating ambivalence in this area. Conversely, the dimension of neglect, which relates to giving up in response to difficulty, had the lowest prevalence of burnout symptoms. In this category, fewer than half of the students endorsed the statements. The highest agreement was for Q9, where 49% of students reported they “stop making an effort” when results are not good. The tendency to give up when faced with an obstacle (Q10, 46%), difficulty (Q11, 41%), or when the effort was insufficient (Q12, 41%) was less common. This suggests that while students feel overloaded and underdeveloped, the majority maintain their efforts and persistence in the face of academic challenges.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of questions used in the survey.

The analysis revealed a definite pattern. The Overload and Lack of Development categories yielded statistically significant responses, as indicated by p-values that were much lower than 0.001. Since the mean scores for these items were all above 3.0, this indicates that students significantly agreed with statements related to feeling overworked and experiencing a lack of professional development. In contrast, the results were mixed within the neglect category. While the response to Q9 (“When the results of my studies are not good at all, I stop making an effort”) was statistically significant (p = 0.001), the mean responses for Q10, Q11, and Q12 were not significantly different from neutral (Table 2). This suggests that while students feel burdened, the majority do not significantly express a tendency to give up when faced with obstacles or difficulties. The average student answers for each burnout area are displayed in Table 3. Cronbach for internal reliability of the 3 domains was high, as seen in Table 4.

Table 2.

Responses about students’ academic experiences.

Table 3.

Shows the average student responses for each burnout category.

Table 4.

Results of the Qualitative Cronbach’s Alpha Reliability Analysis for the questionnaire dimensions.

3.3. Effect of Gender on Burnout Scores of Dental Students (Mann–Whitney U Test)

Gender-stratified analysis using the Mann–Whitney U test revealed statistically significant differences in burnout dimensions between male and female dental students. Female students exhibited significantly higher overload scores (Mdn = 3.2 vs. 3.0, p = 0.032, r = 0.14) and elevated neglect behaviors (Mdn = 2.9 vs. 2.6, p = 0.045, r = 0.13) relative to male counterparts. Total burnout scores demonstrated the most pronounced gender disparity, with female students reporting substantially higher overall burnout (Mdn = 3.1 vs. 2.8, p = 0.005, r = 0.19), representing the largest observed effect size and approaching small-to-medium practical significance. In contrast, perceived lack of development opportunities exhibited no significant gender-based differences (p = 0.210), with both groups reporting comparable median scores (female: 2.9; male: 2.8), suggesting that developmental concerns are distributed uniformly across genders. Whilst Mann–Whitney U analysis confirmed statistical significance across these comparisons, effect sizes remained modest, indicating that although gender-based disparities exist at the population level, substantial inter-individual variation within each gender cohort persists. These findings suggest that gender alone does not fully account for burnout heterogeneity, and multifactorial influences beyond sex contribute substantially to differential burnout trajectories among dental students.

3.4. Effect of Academic Year on Burnout Scores of Dental Students (Kruskal–Wallis Test)

The Kruskal–Wallis test is used in this analysis to explore variations in academic burnout scores among dental students over a four-year period. Kruskal–Wallis analysis revealed highly significant burnout differences across academic years (H = 18.456, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.059). Fourth-year students demonstrated the highest total burnout scores (Mdn = 3.45), with a consistent downward progression through fifth year (Mdn = 3.28), sixth year (Mdn = 3.22), to dental interns (Mdn = 3.18), suggesting an amelioration of burnout symptoms in advanced academic stages. Neglect behaviors exhibited particularly pronounced year-based variation (H = 15.923, p = 0.001), with fourth-year students reporting substantially elevated disengagement scores (Mdn = 3.63) relative to other cohorts, indicating heightened vulnerability to disengagement and reduced effort when confronted with academic or clinical difficulties during the critical intermediate year. Perceived academic overload demonstrated a parallel pattern (H = 12.847, p = 0.005), with fourth-year students experiencing the highest workload burden (Mdn = 3.52) compared to dental interns (Mdn = 3.22), suggesting that curriculum intensity peaks during intermediate years. Descriptive Statistics by effect of burnout domains on the Academic Year are shown in Table 5. Conversely, perceived lack of development opportunities showed modest but statistically significant year-related differences (H = 8.234, p = 0.041), with a less pronounced gradient across academic years, implying that developmental concerns are more uniformly distributed across the curriculum and less dependent on academic progression. Collectively, these findings indicate that burnout is not uniformly distributed across dental training, with fourth-year students representing a particularly vulnerable cohort requiring targeted intervention and support.

Table 5.

Descriptive Statistics by effect of burnout domains on Academic Year.

4. Discussion

The current study revealed a significant prevalence of academic overload and a perceived lack of developmental opportunities among dental students, consistent with broader trends in higher education [19]. Burnout prevalence varies significantly across regions and populations owing to diverse academic structures, cultural contexts, and measurement instruments. Studies have consistently indicated a high yet variable prevalence of burnout symptoms among dental student cohorts. For instance, research in the United Arab Emirates utilized the Burnout Clinical Subtype Questionnaire-12-Student Survey, which shares similar dimensions with our instrument, to estimate the burnout prevalence among dental students [12]. A study from Pakistan also highlighted a significant prevalence of burnout and stress among dental students, although specific numerical prevalence rates can differ based on assessment criteria [9]. The high endorsement of statements like “I think I invest more than is healthy in my commitment to my studies” and “I neglect my personal life because of pursuing great objectives in studying” aligns with previous research on the intense academic burden faced by dental students [9,12]. A substantial proportion of students reported sacrificing personal well-being and leisure for academic pursuits, indicating a pervasive culture of overcommitment [12]. The mean age of the participants was 23.5 years (SD = 1.8 years), a demographic profile consistent with similar studies on dental student burnout [12,20]. This demographic breakdown facilitates the exploration of how different stages of dental education influence burnout prevalence and manifestation. For example, a UAE study found an average overload score of 3.40 among 385 dental students, indicating agreement with feeling overwhelmed, while the average lack of development score was 2.90, suggesting uncertainty regarding professional growth [12]. This aligns with findings from a study in Pakistan involving 274 dental students, with a mean age of 21.9 years; most participants were female, highlighting a common demographic trend in dental burnout research [9]. Similarly, another study in Istanbul, Turkey, involving fourth- and fifth-year dental students, identified a significant relationship between burnout, stress, and perceived social support during the COVID-19 pandemic [21]. The observed patterns regarding academic overload, where students invest more than is healthy in their studies and neglect personal life, corroborate findings from multiple studies that identify rigorous curricula and high-stakes examinations as primary stressors for dental students [2,9,12]. The representation of various academic levels, particularly the significant proportion of interns and senior students, is crucial given that stressors tend to intensify in the later years of dental education [12].

Our findings indicate that burnout manifestations among dental students at King Khalid University are most pronounced in the Overload and Lack of Development dimensions, whereas neglect appears to be less prevalent. This pattern offers a nuanced understanding of how academic pressure translates into psychological strain. The Overload dimension exhibited the highest prevalence of burnout indicators, with 58% of participants agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement, “I think I invest more than is healthy in my commitment to my studies.” Furthermore, 53% felt that they were neglecting their personal life, endangering their health, and ignoring their own needs to meet academic demands. This suggests that a significant proportion of students experience high academic pressure, leading to personal sacrifice. These findings strongly resonate with previous research identifying the intense academic workload and demanding clinical training as primary stressors in dental education [9,12]. Studies have consistently highlighted that students in demanding fields often invest an unhealthy amount of effort, neglect personal life, and even endanger their health in pursuit of academic success [9,12]. The average overload score of 3.40 reported in a UAE study, where students agreed with feeling overwhelmed, further supports the pervasive nature of this dimension [12]. This dimension directly reflects the emotional exhaustion component of burnout, characterized by physical and emotional exhaustion due to prolonged academic demands [6]. Similarly, 57.7% of dental students in a Pakistani study affirmed that they invested more than was healthy in their studies, and 57.7% reported neglecting their personal lives for academic objectives, mirroring the high agreement rates observed in the current investigation regarding Q1 and Q2 [9,12]. This alignment underscores the universality of academic overload as a significant contributor to burnout among dental students across diverse geographical and institutional contexts [9]. Regarding the Lack of Development dimension, more than half of the students expressed dissatisfaction with their personal and professional growth. Specifically, 57% agreed or strongly agreed that they “would like to study something else that would be more challenging,” and 51% felt their current studies were “hampering the development of my abilities” and that they could “better develop my talent” elsewhere. While 47% felt that their studies did not provide opportunities for development, indicating some ambivalence, the overall sentiment pointed towards a significant desire for more fulfilling and challenging educational experiences. This aligns with findings from the UAE study, where the average lack of development score was 2.90, suggesting uncertainty regarding professional growth [12]. The feeling that their studies hinder ability development is a critical indicator of professional inefficiency and reduced personal accomplishment, which are core components of burnout [6]. Such sentiments can lead students to question their career choices and seek alternative paths for improvement [12]. The demanding nature of dental programs, coupled with concerns about future employment and skills, can contribute to this sense of stagnation [11]. This perceived stagnation is often exacerbated by a curriculum that may not sufficiently emphasize critical thinking, research, or advanced clinical skills, leading to a sense of unfulfilled potential among students [17]. The impact of burnout is severe, extending beyond academic performance to detrimentally affect overall well-being and long-term career prospects [9,15]. It is a significant predictor of suicidal ideation and academic dropout [9] and a strong predictor of mental health issues such as anxiety and depressive disorders [12].

Medical and dental students have a higher propensity for mental health challenges than the general population [3]. These consequences impair academic success, interpersonal relationships, and career prospects [3]. Recognizing this, early identification of burnout among dental students through screening is crucial, allowing for timely interventions and support mechanisms to mitigate these adverse effects on both physical and mental health [17]. This proactive approach can foster a more supportive educational environment, ultimately enhancing student well-being and academic achievement [1,22]. Conversely, the Neglect dimension demonstrated the lowest prevalence of burnout symptoms. Less than half the students endorsed statements related to giving up in the face of difficulty. The highest agreement was for Q9, where 49% reported they “stop making an effort” when results are not good. The tendency to give up when faced with an obstacle, difficulty, or insufficient effort is less common. This suggests that despite feelings of overload and underdeveloped potential, the majority of students maintain persistence and effort when confronted with academic challenges. This finding might reflect a degree of resilience or a strong drive to succeed among dental students at King Khalid University, differentiating them from studies where depersonalization or cynicism, a component related to neglect or indifference, is more prominent [6]. While other studies recognize “neglect” as an integral part of educational burnout, defined as giving up in response to obstacles or ignoring one’s own needs [9,12], its lower prevalence in our sample could indicate that students, even when feeling overwhelmed, continue to engage, albeit with some degree of detachment, as indicated by the 49% for Q9. While our study did not provide a single overall burnout prevalence rate, the high percentages within the Overload and Lack of Development dimensions suggest that a significant portion of the student body experienced considerable psychological distress. This is consistent with the global concern regarding burnout among medical and dental students, with reported rates varying widely [7,8].

4.1. Implications for Dental Education

The findings of this study carry important theoretical and practical implications. Specifically, the utilization of the BCSQ-12-SS allows this research to move beyond general stress and categorize burnout into specific clinical subtypes (Overload, Lack of Development, Neglect). This methodological approach enables more precise psychiatric screening in high-pressure medical environments. The prominence of the Lack of Development dimension challenges the traditional exhaustion-centered conceptualization of burnout and aligns with perspectives grounded in Self-Determination Theory, which emphasizes competence, autonomy, and growth as essential psychological needs. The results suggest that dental curricula may insufficiently support students’ developmental needs, thereby contributing to motivational decline and reduced academic engagement. Practically, the observation that students expressed a desire for more challenging and growth-oriented learning experiences indicates a need for curricular reform that moves beyond merely reducing workload. Instead, programs should aim to enhance engagement through active learning strategies, greater integration of hands-on and early clinical exposure, and opportunities that foster skill development and autonomy. Additionally, to mitigate the high levels of Overload, we recommend institutional policy changes such as the adoption of pass/fail grading systems, structured protected time for rest and self-care, and workload redistribution across semesters. These should be complemented by multilevel interventions, including formal mentorship programs, strengthened internship training frameworks, accessible mental health services, resilience-building workshops, and routine screening initiatives to identify burnout early and provide timely support.

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

This cross-sectional investigation, while offering a snapshot of burnout prevalence among dental students at King Khalid University, has certain limitations. The reliance on self-reported data inherently introduces the possibility of a response bias. Furthermore, due to its cross-sectional design, this study could not establish a causal link between the identified variables and burnout. Future research endeavors would benefit significantly from longitudinal studies to meticulously track the progression of burnout over time and evaluate the efficacy of various intervention strategies. Additionally, qualitative research methodologies could yield more profound insights into the lived experiences of dental students, shedding light on the specific cultural and academic determinants that contribute to burnout within the Saudi Arabian academic environment. A comprehensive understanding of burnout etiology would also be enriched by exploring the intricate interplay between individual predispositions and environmental factors.

5. Conclusions

This study establishes that dental students at King Khalid University experience significant levels of burnout, predominantly manifesting as academic overload and a perceived lack of professional development. These specific dimensions serve as critical drivers of distress for over half the cohort and act as independent predictors for clinical psychiatric morbidities. While the low prevalence of neglect behaviors indicates a resilient student body that persists despite challenges, the high rates of exhaustion and dissatisfaction—particularly among female students and fourth-year cohorts—are concerning. These findings necessitate a shift from traditional workload reduction to comprehensive curricular reform that fosters autonomy and competence. Implementing targeted support systems, such as mentorship and mental health screening, is imperative to safeguard the well-being and future efficacy of dental professionals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z., A.M.A., M.S.A.A. and Z.M.A.; methodology, M.Z., F.A.B.A.A., Z.M.A., A.M.A., M.S.A.A., M.S.A. and L.S.A.; investigation, M.Z., A.M.A., M.S.A., L.S.A. and J.A.A.; formal analysis, M.Z., F.A.B.A.A., Z.M.A., M.S.A., R.H.A., L.S.A. and J.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z., F.A.B.A.A., Z.M.A., A.M.A., M.S.A.A. and J.A.A.; writing—review and editing, M.Z., F.A.B.A.A., Z.M.A., M.S.A., R.H.A., L.S.A. and J.A.A.; supervision, M.Z., F.A.B.A.A. and Z.M.A.; project administration M.Z. and F.A.B.A.A.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Scientific Research Committee of the College of Dentistry at King Khalid University (Approval Code: IRB/KKU/COD/ETH/2023-24/040; Approval Date: 26 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Asiri, A. Saudi Arabian students in postgraduate dental programs: Investigating factors associated with burnout. F1000Research 2022, 11, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.Q.; Ahmad, Z.; Muhammad, M.; Binrayes, A.; Niazi, I.; Nawabi, S.; Abulhamael, A.M.; Habib, S.R. Burnout level evaluation of undergraduate dental college students at middle eastern university. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhilali, K.A.A.; Husni, M.; Almarabheh, A. Frequency of burnout in dental students and its relationship with stress level, depressive, and anxiety state. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2024, 31, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer, B.; Sıddıkoğlu, D. Relationship between work-related musculoskeletal symptoms and burnout symptoms among preclinical and clinical dental students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2025, 26, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauca-Bajaña, L.; Lascano, L.C.; Castellón, L.J.; Cevallos, C.C.; Cevallos-Pozo, G.; Ron, B.V.; Vieira e Silva, F.F.; Perez-Sayans, M. The Prevalence of the Burnout Syndrome and Factors Associated in the Students of Dentistry in Integral Clinic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Dent. 2023, 1, 5576835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.R.; Fernandes, S.M.; Fialho-Silva, I.; Cerqueira-Silva, T.; Miranda-Scippa, Â.; Almeida, A.G. Burnout syndrome and resilience in medical students from a Brazilian public college in Salvador, Brazil. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2021, 44, e20200187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, H.; Pikó, B. Risk and protective factors of student burnout among medical students: A multivariate analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, A.; Ali, S.; Issrani, R.; Sethi, A.; Khattak, O.; Iqbal, A. Burnout among Dental Students of Private and Public Dental Colleges in Pakistan—A Cross-Sectional Study. Pesqui. Bras. Odontopediatria Clínica Integr. 2024, 24, e220176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, A. The Protective Role of Resilience in Emotional Exhaustion Among Dental Students at Clinical Levels. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohe, D.E.; Barrier, P.A.; Clark, M.M.; Cook, D.A.; Vickers, K.S.; Decker, P.A. The benefits of pass-fail grading on stress, mood, and group cohesion in medical school. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2006, 81, 1443–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rawi, N.; Yacoub, A.; Zaouali, A.; Salloum, L.; Afash, N.; Shazli, O.A.; Elyan, Z. Prevalence of Burnout among Dental Students during COVID-19 Lockdown in UAE. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2021, 22, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takefuji, Y. Worldwide burnout in dentists. BDJ 2024, 236, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossio-Alva, B.A.; Corrales-Reyes, I.E.; Herrera-Plasencia, P.M.; Mejía, C.R. Prevalence and factors associated with burnout in dental students of seven Cuban universities. Front. Educ. 2025, 9, 1488937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdino, M.J.Q.; de Almeida, L.P.B.M.; da Silva, L.F.R.; Cremer, E.; Scholze, A.R.; Martins, J.T.; Lourenço Haddad, M.C.F. Burnout among nursing students: A mixed method study. Investig. Educ. Enfermería 2020, 38, e07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.; Lobo, V.M.; dos Santos Florenciano, M.S.; Morais, M.A.B.; Barbosa, M.P.D.F. Burnout in medical students: A longitudinal study in a Portuguese medical school. Glob. Ment. Health 2023, 10, e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebbi, S.Z.; Yazdani, R.; Talebi, M.; Pakdaman, A.; Heft, M.W.; Bahramian, H. Burn out among Iranian dental students: Psychometric properties of burnout clinical subtype questionnaire (BCSQ-12-SS) and its correlates. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, I.; Eroje, A.B.I.; Tikare, S.; Togoo, R.A.; Soliman, A.E.-N.M.; Rao, G.R. Psychometric properties and validation of the Arabic Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey in Saudi dental students. Saudi J. Med. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, A.; Chaabna, K.; Sheikh, J.I.; Mamtani, R.; Jithesh, A.; Khawaja, S.; Cheema, S. Burnout increased among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, S.M.; Chaturvedi, S.; Hezam, A.A.; Alshahrani, A.A.S.; Alkhurays, M.; Moaleem, M.M.A.; Alqhtani, R.A.M.; Asiri, B.M.A.; Zahir, S.E.A. Prevalence of burnout and practice-related risk factors among Saudi Board dental residents using the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A survey-based cross-sectional study. Medicine 2023, 102, e35528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, C.; Dikicier, S.; Atay, A. Assessment of burnout level among clinical dental students during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afshar, M.K.; Nejad, S.; Afshar, M.K. Academic burnout and its related factors among dental students in southeast Iran: A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.