Risk of Self-Harm in Patients with Kleptomania: A Population-Based Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

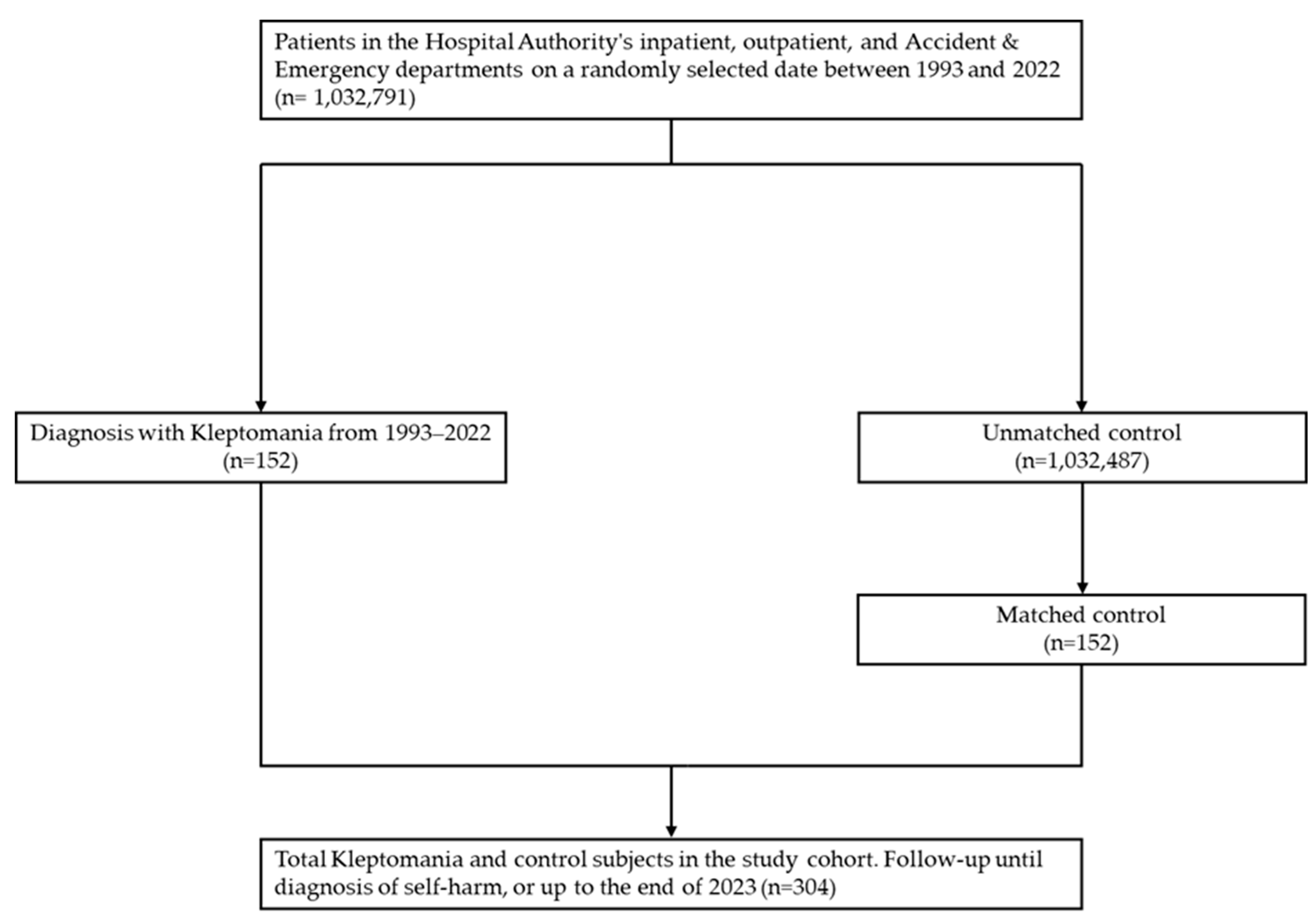

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. KTM Cases

2.3. Non-KTM Comparators

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Outcome Measurement

2.6. Statistical Analysis

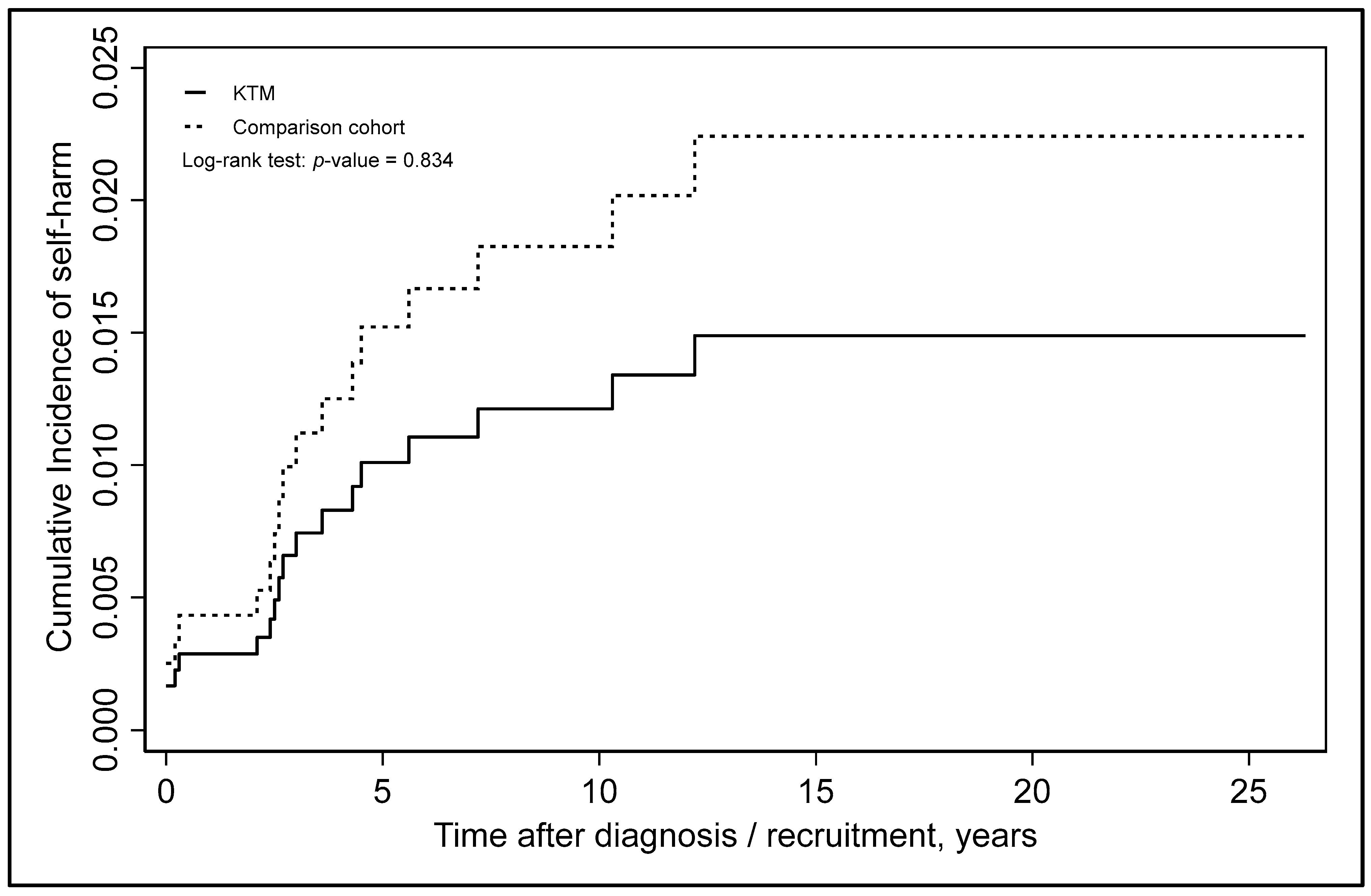

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Torales, J.; González, I.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; Ventriglio, A. Kleptomania as a neglected disorder in psychiatry. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2020, 32, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Huang, F.R.; Liu, D.H. Kleptomania: Recent advances in symptoms, etiology and treatment. Curr. Med. Sci. 2018, 38, 937–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthey, A. Nouvelles Recherches sur les Maladies de L’esprit: Précédées de Considérations sur les Difficultés de L’art de Guérir; Paschoud: Geneva, Switzerland, 1816. [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton, R.A.; Punj, G.N. Kleptomania: A brief intellectual history. In Proceedings of the Conference on Historical Analysis and Research in Marketing 2003, Detroit, MI, USA, 1–4 May 2003; Volume 11, pp. 201–209. [Google Scholar]

- Marc, C.C.; Esquirol, E. Sur un cas de suspicion de folie chez une femme inculpee de vol. Ann. D’Hyg. Publique 1838, 40, 435. [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton, R.A. Psychoanalyzing kleptomania. Mark. Theory 2007, 7, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stekel, W.; Van Teslaar, J.S. Peculiarites of Behavior: Wandering Mania, Dipsomania, Cleptomania, Pyromania and Allied Impulsive Acts; H. Liveright: New York, NY, USA, 1924. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mayo Clinic. Kleptomania. Updated 30 September 2022. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/kleptomania/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20364753 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- McElroy, S.L.; Hudson, J.I.; Pope, H.G.; Keck, P.E. Kleptomania: Clinical characteristics and associated psychopathology. Psychol. Med. 1991, 21, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, M.J. Kleptomania: Making sense of the nonsensical. Am. J. Psychiatry 1991, 148, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboujaoude, E.; Gamel, N.; Koran, L.M. Overview of kleptomania and phenomenological description of 40 patients. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 6, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talih, F.R. Kleptomania and potential exacerbating factors: A review and case report. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 8, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland Clinic. Kleptomania. Updated 15 June 2022. Available online: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/9878-kleptomania (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Presta, S.; Marazziti, D.; Dell’Osso, L.; Pfanner, C.; Pallanti, S.; Cassano, G.B. Kleptomania: Clinical features and comorbidity in an Italian sample. Compr. Psychiatry 2002, 43, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, S.L.; Pope, H.G., Jr.; Hudson, J.I.; Keck, P.E., Jr.; White, K.L. Kleptomania: A report of 20 cases. Am. J. Psychiatry 1991, 148, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.E.; Odlaug, B.L. Kleptomania: Clinical characteristics and treatment. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2008, 30, S11–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylé, F.J.; Caci, H.; Millet, B.; Richa, S.; Olié, J.P. Psychopathology and comorbidity of psychiatric disorders in patients with kleptomania. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 1509–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, J.E.; Odlaug, B.L.; Davis, A.A.; Kim, S.W. Legal consequences of kleptomania. Psychiatr. Q. 2009, 80, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum, A.W.; Odlaug, B.L.; Redden, S.A.; Grant, J.E. Stealing behavior and impulsivity in individuals with kleptomania who have been arrested for shoplifting. Compr. Psychiatry 2018, 80, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biomy, S.R. Cognitive behavioral therapy for kleptomania: A case study. Int. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. J. 2020, 14, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.E.; Odlaug, B.L. Impulse control disorders. In Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Refractory Cases: Turning Failure Into Success; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 231–254. [Google Scholar]

- Asami, Y.; Nomura, K.; Shimada, H.; Nakagawa, K.; Sugano, M.; Koshiba, A.; Ohishi, Y.; Ohishi, H.; Ohishi, M. Cognitive behavioural group therapy with mindfulness for kleptomania: An open trial. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2022, 15, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.E. Understanding and treating kleptomania: New models and new treatments. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2006, 43, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Krakowski, M. Violence and serotonin: Influence of impulse control, affect regulation, and social functioning. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2003, 15, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannon, P.N.; Iancu, I.; Grunhaus, L. Naltrexone treatment in kleptomanic patients. Hum. Psychopharmacol. Clin. Exp. 1999, 14, 583–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannon, P.N. Topiramate for the treatment of kleptomania: A case series and review of the literature. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2003, 26, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmetz, G.F.; McElroy, S.L.; Collins, D.J. Response to kleptomania and mixed mania to valproate. Am. J. Psychiatry 1997, 154, 580–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannon, P.N.; Aizer, A.; Lowengrub, K. Kleptomania: Differential diagnosis and treatment modalities. Curr. Psychiatry Rev. 2006, 2, 281–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizer, A.; Lowengrub, K.; Dannon, P.N. Kleptomania after head trauma: Two case reports and combination treatment strategies. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2004, 27, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Christianini, A.R.; Hodgins, D.C.; Tavares, H. Impairments of kleptomania: What are they? Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2017, 39, 279–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odlaug, B.L.; Grant, J.E.; Kim, S.W. Suicide attempts in 107 adolescents and adults with kleptomania. Arch. Suicide Res. 2012, 16, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangot, A.G. Kleptomania: Beyond serotonin. J. Neurosci. Rural. Pract. 2014, 5, S105–S106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, J.A.; Potenza, M.N. The neurobiology and genetics of impulse control disorders: Relationships to drug addictions. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008, 75, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.; Patrick, C.J.; Kennealy, P.J. Role of serotonin and dopamine system interactions in the neurobiology of impulsive aggression and its comorbidity with other clinical disorders. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2008, 13, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Heeringen, K. The neurobiology of suicide and suicidality. Can. J. Psychiatry 2003, 48, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laporte, N.; Klein Tuente, S.; Ozolins, A.; Westrin, Å.; Westling, S.; Wallinius, M. Emotion regulation and self-harm among forensic psychiatric patients. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 710751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Pierro, R.; Sarno, I.; Gallucci, M.; Madeddu, F. Nonsuicidal self-injury as an affect-regulation strategy and the moderating role of impulsivity. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2014, 19, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, T.; Egglishaw, A.; Sood, M. Does childhood trauma predict impulsive spending in later life? An analysis of the mediating roles of impulsivity and emotion regulation. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2024, 17, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroozi Homayoon, M.; Gohari, F.; Sadri Damirchi, E. Developing a Self-harm Model Based on Cognitive Emotion Regulation and Childhood Trauma With the Mediating Role of Insecure Attachment Styles in Students of Ardabil City, Iran: A Descriptive Study. Pract. Clin. Psychol. 2025, 13, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munguía, L.; Baenas-Soto, I.; Granero, R.; Fábregas-Balcells, M.; Gaspar-Pérez, A.; Rosinska, M.; Potenza, M.N.; Cuquerella, Á.; Tapia-Martínez, J.; Cabús-Grange, R.M.; et al. Kleptomania on the impulsive–compulsive spectrum. Clinical and therapeutic considerations for women. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasalo, E.; Bergman, B.; Toth, J. Personality traits and psychiatric and somatic morbidity among kleptomaniacs. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1996, 94, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.E.; Odlaug, B.L.; Medeiros, G.; Christianine, A.R.; Tavares, H. Cross-cultural comparison of compulsive stealing (kleptomania). Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 2015, 27, 150–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, V.C.; Wang, T.N.; Liao, Y.T.; Lin, T.C.; Stewart, R.; Lee, C.T. Asthma and self-harm: A population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J. Psychosom. Res. 2014, 77, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GovHK. GovHK: Overview of the Health Care System in Hong Kong [Internet]. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.hk/en/residents/health/hosp/overview.htm (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Hospital Authority. Hospital Authority Annual Report 2020–2021 [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://www.ha.org.hk/haho/ho/cc/HA_Annual_Report_2020-21_en.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Sing, C.W.; Woo, Y.C.; Lee, A.; Lam, J.; Chu, J.; Wong, I.C.K.; Cheung, C.L. Validity of major osteoporotic fracture diagnosis codes in the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System in Hong Kong. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2017, 26, 973–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harnod, T.; Lin, C.L.; Kao, C.H. Risk of suicide attempt in poststroke patients: A population-based cohort study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e007830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloskey, M.S.; Ammerman, B.A. Suicidal behavior and aggression-related disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 22, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nock, M.K.; Hwang, I.; Sampson, N.; Kessler, R.C.; Angermeyer, M.; Beautrais, A.; Borges, G.; Bromet, E.; Bruffaerts, R.; De Girolamo, G.; et al. Cross-national analysis of the associations among mental disorders and suicidal behavior: Findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Hwang, I.; Sampson, N.A.; Kessler, R.C. Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol. Psychiatry 2010, 15, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Stein, M.B.; Heeringa, S.G.; Ursano, R.J.; Colpe, L.J.; Fullerton, C.S.; Hwang, I.; Naifeh, J.A.; Sampson, N.A.; Schoenbaum, M.; et al. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behavior among soldiers: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockwood, J. Impulsivity and Self-Harm in Adolescence. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dannon, P.N.; Lowengrub, K.M.; Iancu, I.; Kotler, M. Kleptomania: Comorbid psychiatric diagnosis in patients and their families. Psychopathology 2004, 37, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco-Fontecilla, H.; Fernández-Fernández, R.; Colino, L.; Fajardo, L.; Perteguer-Barrio, R.; De Leon, J. The addictive model of self-harming (non-suicidal and suicidal) behavior. Front. Psychiatry 2016, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinhoff, A.; Cavelti, M.; Koenig, J.; Reichl, C.; Kaess, M. Symptom shifting from nonsuicidal self-injury to substance use and borderline personality pathology. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2444192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Swannell, S.V.; Hazell, P.L.; Harrison, J.E.; Taylor, A.W. Self-injury in Australia: A community survey. Med. J. Aust. 2010, 193, 506–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morey, Y.; Mellon, D.; Dailami, N.; Verne, J.; Tapp, A. Adolescent self-harm in the community: An update on prevalence using a self-report survey of adolescents aged 13–18 in England. J. Public Health 2017, 39, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, T.E.; Vaughan-Sarrazin, M.; Rosenthal, G.E. Variations in the associations between psychiatric comorbidity and hospital mortality according to the method of identifying psychiatric diagnoses. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sariaslan, A.; Sharpe, M.; Larsson, H.; Wolf, A.; Lichtenstein, P.; Fazel, S. Psychiatric comorbidity and risk of premature mortality and suicide among those with chronic respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes in Sweden: A nationwide matched cohort study of over 1 million patients and their unaffected siblings. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1003864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assimon, M.M. Confounding in observational studies evaluating the safety and effectiveness of medical treatments. Kidney360 2021, 2, 1156–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, Y.; Luo, H.; Wong, G.H.Y.; Tang, J.Y.M.; Lam, T.C.; Wong, I.C.K.; Yip, P.S.F. Risk of self-harm after the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in Hong Kong, 2000–2010: A nested case-control study. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skegg, K. Self-harm. Lancet 2005, 366, 1471–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlattani, T.; D’Amelio, C.; Capelli, F.; Mantenuto, S.; Rossi, R.; Socci, V.; Stratta, P.; Di Stefano, R.; Rossi, A.; Pacitti, F. Suicide and COVID-19: A rapid scoping review. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2023, 22, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, S.R.; Redden, S.A.; Grant, J.E. Associations between self-harm and distinct types of impulsivity. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 250, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Kleptomania (n = 152) | Comparison Cohort (n = 152) | p-Value a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1.000 | ||

| Male Female | 45 (29.6) 107 (70.4) | 45 (29.6) 107 (70.4) | |

| Age | 1.000 | ||

| </=10 11–20 21–40 41–60 61–80 >/=81 | 2 (1.3) 9 (5.9) 46 (30.3) 84 (55.3) 11 (7.2) 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) 9 (5.9) 46 (30.3) 84 (55.3) 11 (7.2) 0 (0) | |

| Mean age | 42.3 ± 43.5 | 42.3 ± 43.5 | 1.000 b |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Chinese non-Chinese | 138 (90.8) 14 (9.2) | 147 (96.7) 5 (3.3) | 0.033 |

| District | |||

| New Territories Kowloon Hong Kong Island Other Island | 65 (42.8) 43 (28.3) 43 (28.3) 1 (0.7) | 39 (25.7) 43 (28.3) 70 (46.1) 0 (0) | 0.002 1.000 0.001 1.000 |

| History of depression/bipolar disorder | 54 (35.5) | 12 (7.9) | <0.001 |

| History of ADHD | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| History of personality disorders | 14 (9.2) | 3 (2.0) | 0.010 |

| History of substance use disorders | 18 (11.8) | 20 (13.2) | 0.863 |

| Average time to self-harm (years) | 4.9 ± 4.0 | 1.8 ± 1.6 | 0.063 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chan, S.K.Y.; Tsoi, K.K.F.; Yip, T.C.F.; Liew, V.W.J.; Tang, W.K. Risk of Self-Harm in Patients with Kleptomania: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Psychiatry Int. 2026, 7, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010014

Chan SKY, Tsoi KKF, Yip TCF, Liew VWJ, Tang WK. Risk of Self-Harm in Patients with Kleptomania: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Psychiatry International. 2026; 7(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleChan, Selina Kit Yi, Kelvin K. F. Tsoi, Terry Cheuk Fung Yip, Vivien Wei Jun Liew, and Wai Kwong Tang. 2026. "Risk of Self-Harm in Patients with Kleptomania: A Population-Based Cohort Study" Psychiatry International 7, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010014

APA StyleChan, S. K. Y., Tsoi, K. K. F., Yip, T. C. F., Liew, V. W. J., & Tang, W. K. (2026). Risk of Self-Harm in Patients with Kleptomania: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Psychiatry International, 7(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010014