Abstract

Mental disorders have significantly increased worldwide, with depression affecting over 280 million people. Up to 60% of individuals with major depressive disorder experience concurrent anxiety, both of which can lead to suicide. While social and cultural factors contribute to mental disorders, recent studies link these conditions to genetic, neurophysiological, and biochemical factors, including serum lipid levels. This study investigates the association between serum lipid levels and depressive symptoms in the Los Altos Sur region of Jalisco, Mexico. Forty-two participants with depressive symptoms and eighty-four controls were recruited. Participants underwent psychometric assessments and lipid profile assays. The results showed significant differences between cases and controls in total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL, and VLDL levels. Cases had higher rates of hypocholesterolemia and more frequent depressive and anxiety symptoms, as well suicidal risk. Hypocholesterolemia was significantly associated with depressive symptoms. Differences for cases grouped by depressive symptoms and hopelessness were found in HDL. Physical activity was found as a protective factor for depressive and anxiety symptoms. This study demonstrates the association of serum lipid levels with mental health conditions, suggesting that cholesterol levels are related to increased vulnerability to depression and hopelessness. Understanding these associations can aid in early identification and intervention for at-risk populations.

1. Introduction

Globally, mental disorders have experienced exponential growth in recent decades. The World Health Organization [1] estimates that depression affects more than 280 million people. Additionally, up to 60% of individuals with major depressive disorder experience concurrent anxiety [2]. These conditions can be determinants for suicide [3,4]. Suicide rates vary among age groups, but the tendency is to increase in older age groups; older adolescents and young adults tend to commit suicide more often than young adolescents and children [4,5].

While it has been hypothesized that mental disorders are phenomena rooted in social and cultural factors, in recent years, they have been linked to genetic, neurophysiological, and biochemical factors, such as depression [6,7] or suicidal behavior [8,9]. Among these factors is the concentration of lipids in both serum and brain tissue, especially hypocholesterolemia [10,11,12]. Additionally, pandemics are related to long-term increases in the frequency of mental disorders worldwide [13] and augmenting risk factors for suicide [14] such as alcohol consumption [15].

The link between low cholesterol levels and the risk of suicide has attracted considerable attention in scientific research. Several studies have explored the potential link between hypocholesterolemia and psychological vulnerability [10,11,12,16,17,18].

Over the decades, a substantial body of research has supported this intricate relationship, suggesting that serum cholesterol concentration not only plays a fundamental role in cardiovascular health but may also have significant implications for mental well-being [19,20].

Some studies have examined the frequency of hypocholesterolemia in individuals exhibiting a history of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts [3,16]. Despite the intricate nature of this association not being fully elucidated, accumulating evidence suggests a plausible connection between low cholesterol levels and an increased risk of suicidal manifestations [21,22]. Understanding this relationship holds the potential not only for the early identification of populations at risk but also for the formulation of more effective intervention and prevention strategies within the domain of mental health.

Several theories and potential explanations have been proposed in the scientific literature regarding the biological basis of cholesterol and mental health. The first explanation is that cholesterol is indispensable for the integrity and function of cell membranes, including those of the nervous system [23,24]. The second explanation is that cholesterol may play a role in serotonin synthesis, a neurotransmitter linked to mood and emotional regulation [25,26,27]. Another explanation says that low cholesterol levels may be associated with increased inflammation and oxidative stress, biological processes linked to mental health [28,29,30,31]. A fourth hypothesis is centered in mitochondrial biogenesis, the process that ensures the removal of old defective mitochondria by mitophagy, and the replacement by new one, a process that involves cellular functionality [32]. Other studies have found differences in HDL levels [17,18,21] and hypercholesterolemia [16,33], while some report no differences in total cholesterol, HDL, and LDL [18,34]. Finally, reduced cholesterol levels interact with other risk factors for mental health [35].

Enhancing our comprehension of the biological factors contributing to symptoms and personality traits in individuals at risk of suicide may pave the way for more effective preventive and therapeutic approaches. In the present study, we, therefore, compare the serum lipid levels and depressive symptoms in individuals with and without symptoms. Also, in an exploratory manner, we examined within the case group the associations between lipids and anxiety severity and suicidal risk.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

All subjects gave written informed consent to participate. We recruited forty-two participants with depressive symptoms as cases (BDI-II score > 10 points) and eighty-four participants without psychiatric or neurological antecedents as controls (n = 126, 94 women); participants signed written informed consent. All participants came from the Los Altos Sur region of Jalisco, Mexico, and were native and residents of the area. Cases were matched with controls based on age, gender, and body mass index. Individuals using statins or those with conditions affecting lipid concentrations, such as diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, or liver damage, were excluded.

2.2. Psychometric Assessments

All participants underwent a comprehensive medical history, anthropometry, laboratory tests, and psychometric assessments (including Beck Depression Inventory II [BDI-II], Beck Anxiety Inventory [BAI], Beck Hopelessness Scale [BHS], and Plutchik Suicide Risk Scale [SRS]).

2.3. Lipid Profile Assay

After a night of fasting, venous blood samples from the antecubital vein were collected at 8:00 a.m. in tubes containing EDTA. The samples were immediately placed on ice and centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min to separate plasma from cellular components within 1 h of collection. Plasma levels of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) were determined directly using enzymatic methods from Biosystems (Barcelona, Spain) and processed on the automated clinical chemistry analyzer Flexor EL 200 (Holliston, MA, USA). Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) was calculated using the Friedewald equation, while very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) values were obtained by dividing triglyceride values by 5. It was considered that the cholesterol level was low when it was below 150 mg/dL and high when it was above 200 mg/dL.

2.4. Statistics

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS statistical software version 23.0. Student t-test was used for groupwise comparisons on parametric data. Non-parametric data were analyzed through Mann–Whitney test for groupwise comparisons and Spearman correlation test. All statistical analyses were tested for a two-tailed hypothesis. The alpha-level of significance was set at p < 0.05. To determine the strength of the association of risk and protective factors, chi-square with odds ratio was employed.

Some analyses were performed only for cases that relate to exploring variables related to depressive symptoms and suicidal risk. Criteria for case comparison were determined for each variable out of our selection criteria as follows: BDI-II score: minimal or low symptoms, equal to or less than 19 points, versus moderate or high symptoms, more than 19 points. BAI score: minimal or low symptoms, equal to or less than 15 points, versus moderate or high symptoms, more than 15 points. BHS score: normal or asymptomatic and low symptoms, equal to or less than 8 points, versus moderate or high symptoms, more than 8 points. SRS score: without suicidal risk, equal to or less than 6 points versus with suicidal risk, more than 6 points.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographic Characteristics

The sample consisted of 126 individuals (96 participants were female, ranging from 15 to 77 years old). None of the participants had comorbidities that could affect serum lipid levels. Among them, only 42 participants met the criteria for cases as they exhibited symptoms of depression based on BDI-II scores (>10 points). Additionally, 84 participants without psychiatric or neurological antecedents, matched by age and sex, were selected as controls. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the population sample of Los Altos of Jalisco, examined in this study.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants (case and controls) (n = 126).

Lifestyle characteristics, antecedents, psychometric classification, and serum lipid levels by study group were summarized in Table 2. It is observed that cases had more familiar antecedents of mental illness, higher tobacco consumption, less-frequent physical activity, a lower presence of hypercholesterolemia, and higher levels of hypocholesterolemia compared with controls. It is noteworthy that controls showed an absence of anxiety symptoms and suicidal risk indicators, while these were prevalent in the case group.

Table 2.

Lifestyle characteristics, antecedents, and serum levels by study group.

3.2. Psychometric Assessment and Serum Lipid Levels

As expected, due to selection criteria, significant differences were observed between the case and control groups for BDI-II, also for BAI, BHS, and SRS scores (Table 3). It is important to emphasize that the effect size for all comparisons was larger, indicating statistically significant differences (all p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Psychometric assessment scores for BDI-II, BAI, BHS, and SRS between case and control groups.

3.3. Exploration of Psychopathological Symptoms and Suicidal Behavior with Other Variables

Association between serum lipid levels and the presence of psychopathological symptoms was explored, finding a significant association between hypocholesterolemia and the presence of depressive symptoms (classification according to BDI-II score) (χ2 = 15.402, DF = 1, OR = 4.771, C.I. = 2.127–10.701, p = 0.00008). This suggests that, based on the odds ratio, the odds of depressive symptoms were 4.771 times higher if participants had low cholesterol levels.

No significant comparisons using the Mann–Whitney test on cases were found when grouped by BAI score (minimal or low symptoms versus moderate or high symptoms) and SRS (without suicidal risk versus with suicidal risk) for serum lipid levels. But for cases grouped by BDI-II, differences were observed for ‘Normal or asymptomatic and low anxiety symptoms group’ (Mdn = 53.55 mg/dL) versus ‘Moderate or high anxiety symptoms group’ (Mdn = 66.9 mg/dL) (U = 65, z = −2.378, p = 0.017, r = −0.367) for HDL. Also, for cases grouped by BHS, differences were observed on HDL for comparisons between ‘Normal or asymptomatic and low anxiety symptoms group’ (Mdn = 55 mg/dL) versus ‘Moderate or high anxiety symptoms group’ (Mdn = 70 mg/dL) (U = 109, z = −2.2, p = 0.028, r = −0.339).

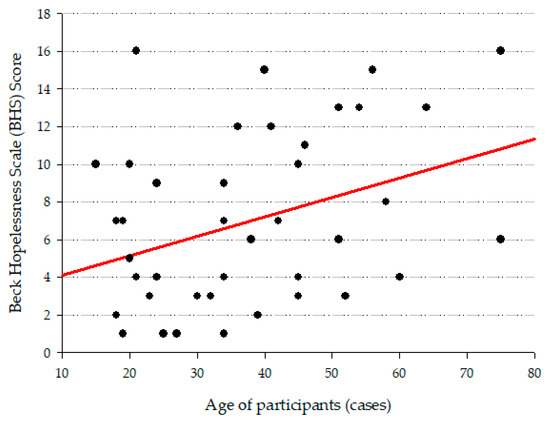

A correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between the age of case group and their scores on Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS), and Plutchik Suicide Risk Scale (SRS). A correlation yielded significant results (Figure 1): a positive correlation with BHS score and age of cases was observed (r = 0.327, p = 0.035).

Figure 1.

Graph that shows the correlation between the age of participants and BHS score.

Finally, additional associations were identified regarding protective factors against psychopathological symptoms; the analysis included data from both groups: cases and controls (Table 4). An association between depressive symptoms and frequent physical activity (χ2 = 8.661, DF = 1), with the odds ratio for cohort engaging in frequent physical activity indicating a 0.596 decrease in the probability of experiencing depressive symptoms. Similarly, another association was found between anxiety symptoms and frequent physical activity (χ2 = 6.204, DF = 1), with the odds ratio for cohort engaging in frequent physical activity indicating a 0.639 probability of experiencing anxiety symptoms.

Table 4.

Association between psychopathological symptoms and suicidal behavior with protective factors.

Analysis by the Mann–Whitney test, including only case group data, demonstrated no significant differences among the frequency of physical activity comparisons.

4. Discussion

The principal finding of this observational case-control study is that individuals with depressive symptoms from the Los Altos Sur region of Mexico exhibit a distinct serum lipid profile characterized by significantly lower levels of total cholesterol, LDL, and VLDL compared to matched controls without psychiatric antecedents. This finding aligns with a growing body of evidence linking hypocholesterolemia to major depressive disorder [11,12,36,37] and reinforces the notion that lipid metabolism may be a relevant biological factor in the pathophysiology of depression in this specific population. To our knowledge, this is the first report to describe such an association in this particular region of Mexico. This finding is especially relevant from a public health perspective, as this population experiences a suicide rate (13.97 per 100,000) [38] that is more than double the national average (6.8 per 100,000) in 2023 [39], highlighting the urgent need for novel approaches to understanding mental health risks in this population.

The biological mechanisms underlying the association between low cholesterol and depression may involve serotonergic neurotransmission and neuronal integrity. Cholesterol is a critical component of lipid rafts in neuronal membranes, which regulate the function of serotonin receptors, such as the 5-HT1A receptor [27]. Low cholesterol levels could disrupt this environment, leading to reduced serotonin signaling and subsequent depressive-like behavior, as demonstrated in animal models [27,37]. Furthermore, the observed hypocholesterolemia might also be a consequence of persistent inflammation and oxidative stress, which are established pathophysiological components of depression [31], and also activation of the HPA axis by chronic stress [31,40]. While our results support this hypothesis, it is important to acknowledge the heterogeneity in the literature, with some studies reporting higher lipid levels in depressed patients [10,11,18,21,41].

No clear explanations of these lipids-levels variances in different populations exist. Cholesterol processing varies due to genetic factors and is correlated with behavioral and mental health characteristics [16]. This suggests that genetic population differences may explain the divergent findings across studies, highlighting the importance of genetics as a risk factor for depression [4,31], and the role of lipids on DNA methylation [42], due to the epigenetic modifications on genes related to stress and depression-like phenotypes [43].

Also, it is stated that a family history of major depression [44] and other disorders [45] is related to the development of depression. Equally, the consumption of tobacco and alcohol is related to depression and anxiety [45,46]. This demonstrates that mental disorders are multicausal, and no simple explanation could be offered.

Another relevant result is the psychometric assessment of depression, anxiety, hopelessness, and suicide risk symptoms, comparing cases and controls. The differences observed demonstrate a robust effect size on measures for depression, anxiety, hopelessness, and suicide risk. This reinforces the results showing hypocholesterolemia associated with depressive symptoms in the case control.

Our results were similar to Segoviano et al. [11] who found differences on cases and controls in TC, LDL, and VLDL. Also, differences between cases were observed, differing from our results; we found differences in only HDL levels when comparing cases by depression or hopelessness. Other studies have found that HDL and other inflammatory indicators are associated with depression [47]; these mechanisms could be characteristic of severe depressive conditions and not for low depressive symptoms.

Depression and anxiety are commonly comorbid disorders [2]. Our results confirm that cases with high scores for depressive symptoms also often exhibit anxiety symptoms. Depression with anxiety comorbidity and depression alone versus anxiety disorder alone show specific serum lipid profiles, with no alterations observed in anxiety disorders alone [41]. It is hypothesized that stress causes depression and anxiety [48], but no concluding studies exist [46]; also, brain circuits and neurotransmitters related to depression [31,49] and anxiety [50] differ, implying common factors for comorbidity [2,49]. Differences on etiology and brain mechanism could explain why cases grouped by BAI scores did not differ.

Hopelessness and suicide risk are related. Our results show differences between cases and controls in BHS and SRS scores, as well as in the presence of suicidal risk. This aligns with a meta-analysis indicating that severe hopelessness predicts the risk of committing suicide [51]. Due to mood and cognition changes by conditions as depression and anxiety, there is an increased risk of suicide attempt and ideation, as noted in other studies [52,53].

Age and hopelessness were positively correlated to the age of cases. Some studies report lower mental health condition symptoms in adults compared to adolescents [54,55]. However, another study in Mexican population did not find an association between age and depressive symptoms [56] as we found. The association between age and hopelessness may be explained by a decrease in cognitive and physical resources along with challenging life events [57,58].

Our study also reinforces the role of frequent physical activity as a protective factor against depressive and anxiety symptoms in the entire sample. Frequent physical activity appears to reduce the risk of significant depressive and anxiety symptoms. Physical activity [59] and physical health [29] are documented protective factors against depression. Some studies explain that factors like BDNF [32,60,61] and kynurenine [61] are promoted by physical activity and exercise. Also, physical activity and exercise promote cortisol (a hormone related to stress response) [62] as inflammatory response regulation [63,64] and also promote mitochondrial biogenesis regulators, influencing buffering of ROS in the brain [32].

Finally, our study had limitations, including a small sample size due to the inclusion criteria for cases and controls. Another limitation was the lack of clinical depression diagnosis in cases like Segoviano et al. [11], which could have provided more robust associations between serum lipid levels and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and suicidal risk. BDI-II, BAI, and BHS discriminate well between clinical and non-clinical samples, but they are detection instruments [65].

These limitations suggest directions for future studies in the general population without stringent filters, as well as larger sample sizes with the same criteria. Studies involving clinical conditions of depression and anxiety or previous suicide attempt could help specifically characterize serum lipid profiles in the Mexican population. Detailed exploration of scale items for better characterization of symptoms related to serum lipid levels is also recommended. Future studies should consider cultural adaptations of BDI-II [66,67] and BAI [67].

Also, it is plausible that exercise-induced adaptations could counteract some of the proposed mechanisms linking low cholesterol and depression, such as inflammation and impaired neurogenesis [32,60], although this interaction needs direct investigation in future studies.

Another important limitation was considering suicide attempts as a single profile. Distinct suicide profiles to attempts and risk have been documented [68]. Future studies could partially address this by using detailed items and categories from the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) and the Plutchik Suicide Risk Scale (SRS).

5. Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that hypocholesterolemia is prevalent among individuals with depressive symptoms in the population from the Los Altos Sur region of Mexico. We established that LDL levels are significantly lower in cases than in controls. Between cases, HDL differs in the severity of depressive symptoms and hopelessness. Anxiety symptoms and suicidal risk were also highly prevalent among cases. Physical activity was identified as a protective factor against depression, potentially due to its role in promoting optimal cellular function, such as through anti-inflammatory effects of mitochondrial biogenesis. Future studies should involve larger, population-based samples and focus on individuals with clinically diagnosed depression to confirm and extend these findings. Overall, this investigation highlights the potential benefits on early detection and intervention for people with depression through serum lipid profile while also contributing to the identification of underlying cellular and molecular pathophysiological mechanisms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.-E.; methodology, S.S.-E.; software, H.A.L.-F.; validation, S.S.-E., M.F.O.-M. and J.B.R.; formal analysis, H.A.L.-F. and S.S.-E.; investigation, J.J.P.-S.; resources, S.S.-E.; data curation, J.J.P.-S. and S.S.-E.; writing—original draft preparation, J.J.P.-S. and S.S.-E.; writing—review and editing, H.A.L.-F. and E.A.R.-L.; visualization, H.A.L.-F. and E.A.R.-L.; supervision, S.S.-E.; project administration, S.S.-E.; funding acquisition, S.S.-E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the COECyTJAL under Grant number 8097-2019. The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the Research Ethics Committee from Los Altos University Center, University of Guadalajara (approval code: CUA/CEI/DIVBIO-03/2021, approval date 12 July 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study, ensuring the confidentiality of their personal data, minimizing risks, and prioritizing their well-being at all times.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed for this study are not publicly available because they contain sensitive personal information from the participants; this confidentiality is protected by the Mexican Federal Law on Protection of Personal Data. However, the data are available to qualified researchers who meet the access criteria for the ethical handling of information, upon reasonable request to the corresponding author and provided that the use of the data is limited to the purposes of the request. The data will be anonymized to guarantee the participants’ privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BAI | Beck Anxiety Inventory |

| BDI-II | Beck Depression Inventory II |

| BHS | Beck Hopelessness Scale |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein cholesterol |

| SRS | Plutchik Suicide Risk Scale |

| TC | Total Cholesterol |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| VLDL | Very-Low-Density Lipoprotein cholesterol |

References

- World Health Organization. Depressive Disorder (Depression). 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- ter Meulen, W.G.; Draisma, S.; van Hemert, A.M.; Schoevers, R.A.; Kupka, R.W.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Penninx, B.W. Depressive and anxiety disorders in concert–A synthesis of findings on comorbidity in the NESDA study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 284, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beekman, A.T.F.; Eikelenboom, M.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Smit, J.H. A 6-year longitudinal study of predictors for suicide attempts in major depressive disorder. Psychol. Med. 2018, 49, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilsen, J. Suicide and Youth: Risk Factors. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenn, C.R.; Kleiman, E.M.; Kellerman, J.; Pollak, O.; Cha, C.B.; Esposito, E.C.; Porter, A.C.; Wyman, P.A.; Boatman, A.E. Annual Research Review: A meta-analytic review of worldwide suicide rates in adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldwaser, E.L.; Aaronson, S.T. Depressive Disorders. In Atlas of Psychiatry; IsHak, W.W., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 531–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.L.; Chen, J.F. Lipid and lipoprotein levels in depressive disorders with melancholic feature or atypical feature and dysthymia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2004, 58, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza-Reig, J.; Julián, M. Association between suicidal ideation and burnout: A meta-analysis. Death Stud. 2024, 48, 1085–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-García, A.; Contreras, C. El suicidio y algunos de sus correlatos neurobiológicos. Prim. Parte. Salud Ment. 2008, 31, 321–329. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.J.; Zhou, Y.J.; Wang, D.F.; Li, Y.; Wang, D.M.; Liu, T.Q.; Zhang, X.Y. Association of Lipid Profile and Suicide Attempts in a Large Sample of First Episode Drug-Naive Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 543632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segoviano-Mendoza, M.; Cárdenas-de la Cruz, M.; Salas-Pacheco, J.; Vázquez-Alaniz, F.; La Llave-León, O.; Castellanos-Juárez, F.; Méndez-Hernández, J.; Barraza-Salas, M.; Miranda-Morales, E.; Arias-Carrión, O.; et al. Hypocholesterolemia is an independent risk factor for depression disorder and suicide attempt in Northern Mexican population. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, S.; Jiménez, N.; Lozano, J.J.; Rubio, A. Concentraciones séricas de colesterol e intento suicida. Med. Interna México 2008, 24, 181–185. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, M.H.; Bhugra, D. Acceleration of Anxiety, Depression, and Suicide: Secondary Effects of Economic Disruption Related to COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 592467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, C.; Gómez Tabares, A.S.; Moreno Méndez, J.H.; Agudelo Osorio, M.P.; Caballo, V.E. Predictive Model of Suicide Risk in Young People: The Mediating Role of Alcohol Consumption. Arch. Suicide Res. 2023, 27, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohi, I.; Chrystoja, B.R.; Rehm, J.; Wells, S.; Monteiro, M.; Ali, S.; Shield, K.D. Changes in alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic and previous pandemics: A systematic review. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 46, 498–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.F.; Ganesh, A.; Mahadevan, S.; Shamli, S.A.; Al-Waili, K.; Al-Mukhaini, S.; Al-Rasadi, K.; Al-Adawi, S. A Comprehensive Neuropsychological Study of Familial Hypercholesterolemia and Its Relationship with Psychosocial Functioning: A Biopsychosocial Approach. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penninx, B.W.; Milaneschi, Y.; Lamers, F.; Vogelzangs, N. Understanding the somatic consequences of depression: Biological mechanisms and the role of depression symptom profile. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.G.; Cai, D.B.; Liu, J.; Liu, R.X.; Wang, S.B.; Tang, Y.Q.; Zheng, W.; Wang, F. Cholesterol and triglyceride levels in first-episode patients with major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of case-control studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 266, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, L.; Henríquez, M.P.; Salazar, C.; Rojas, E.; Echeverría, G.; Love, G.D.; Rigotti, A.; Coe, C.L.; Ryff, C.D. Association between serum sphingolipids and eudaimonic well-being in white U.S. adults. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noerman, S.; Klåvus, A.; Järvelä-Reijonen, E.; Karhunen, L.; Auriola, S.; Korpela, R.; Lappalainen, R.; Kujala, U.M.; Puttonen, S.; Kolehmainen, M.; et al. Plasma lipid profile associates with the improvement of psychological well-being in individuals with perceived stress symptoms. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda, M.S.; Kern, D.M.; Blacketer, C.; Drevets, W.C. Low levels of cholesterol and the cholesterol type are not associated with depression: Results of a cross-sectional NHANES study. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2020, 14, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Castro, T.B.; Genis-Mendoza, A.D.; León-Escalante, D.I.; Hernández-Díaz, Y.; Juárez-Rojop, I.E.; Tovilla-Zárate, C.A.; López-Narváez, M.L.; Marín-Medina, A.; Nicolini, H.; Castillo-Avila, R.G.; et al. Possible Association of Cholesterol as a Biomarker in Suicide Behavior. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Saavedra, O. Colesterol: Función biológica e implicaciones médicas. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Farm. 2012, 43, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ouweneel, A.B.; Thomas, M.J.; Sorci-Thomas, M.G. The ins and outs of lipid rafts: Functions in intracellular cholesterol homeostasis, microparticles, and cell membranes: Thematic Review Series: Biology of Lipid Rafts. J. Lipid Res. 2020, 61, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S.Y. Impaired Cholesterol Metabolism, Neurons, and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Exp. Neurobiol. 2023, 32, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deveau, C.M.; Rodriguez, E.; Schroering, A.; Yamamoto, B.K. Serotonin transporter regulation by cholesterol-independent lipid signaling. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 183, 114349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yang, S.; Mao, Y.; Jia, X.; Zhang, Z. Reduced cholesterol is associated with the depressive-like behavior in rats through modulation of the brain 5-HT1A receptor. Lipids Health Dis. 2015, 14, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerikanou, C.; Valsamidou, E.; Kleftaki, S.A.; Gioxari, A.; Koutoulogenis, K.; Aroutiounova, M.; Stergiou, I.; Kaliora, A.C. Peripheral inflammation is linked with emotion and mental health in people with obesity. A “head to toe” observational study. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1197648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, M.; Köhler-Forsberg, O.; Turner, M.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Wrobel, A.; Firth, J.; Loughman, A.; Reavley, N.J.; McGrath, J.J.; Momen, N.C.; et al. Comorbidity between major depressive disorder and physical diseases: A comprehensive review of epidemiology, mechanisms and management. World Psychiatry 2023, 22, 366–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, S.; Nagappa, A.N.; Patil, C.R. Role of oxidative stress in depression. Drug Discov. Today 2020, 25, 1270–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serafini, G.; Costanza, A.; Aguglia, A.; Amerio, A.; Trabucco, A.; Escelsior, A.; Sher, L.; Amore, M. The Role of Inflammation in the Pathophysiology of Depression and Suicidal Behavior: Implications for Treatment. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 107, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socci, V.; Fagnani, L.; Barlattani, T.; Celenza, G.; Rossi Pacitti, F. Future research perspectives on energy metabolism and mood disorders: A brief narrative review on metabolic status, mitochondrial hypothesis and potential biomarkers. Ital. J. Psychiatry 2025, 11, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez Bagnasco, M. Psychological issues and cognitive impairment in adults with familial hypercholesterolemia. Fam. Pract. 2017, 34, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida Montes, L.G. Concentraciones Séricas de Colesterol, HDL y LDL, en Pacientes Deprimidos con y sin Intento Suicida. Doctoral Dissertation, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico, 1996. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14330/TES01000240172 (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Fusar-Poli, L.; Amerio, A.; Cimpoesu, P.; Natale, A.; Salvi, V.; Zappa, G.; Serafini, G.; Amore, M.; Aguglia, E.; Aguglia, A. Lipid and Glycemic Profiles in Patients with Bipolar Disorder: Cholesterol Levels Are Reduced in Mania. Medicina 2021, 57, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suneson, K.; Asp, M.; Träskman-Bendz, L.; Westrin, Å.; Ambrus, L.; Lindqvist, D. Low total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein associated with aggression and hostility in recent suicide attempters. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 273, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Ding, Y.; Wu, F.; Xie, G.; Hou, J.; Mao, P. Serum lipid levels and suicidality: A meta-analysis of 65 epidemiological studies. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2016, 41, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secretaría de Planeación y Participación Ciudadana de Jalisco. MIDE Jalisco. 2025. Tasa de Suicidio por cada 100mil Habitantes. Available online: https://mide.jalisco.gob.mx/mide/panelCiudadano/tablaDatos?nivelTablaDatos=3&periodicidadTablaDatos=anual&indicadorTablaDatos=191&accionRegreso=mapaMunicipal&municipioTablaDatos= (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática. Estadísticas a Propósito del Día Mundial para la Prevención del Suicidio; Report: 126/25; Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática: Ciudad de México, México, 2024; p. 5. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/aproposito/2024/EAP_Suicidio24.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Juszczyk, G.; Mikulska, J.; Kasperek, K.; Pietrzak, D.; Mrozek, W.; Herbet, M. Chronic Stress and Oxidative Stress as Common Factors of the Pathogenesis of Depression and Alzheimer’s Disease: The Role of Antioxidants in Prevention and Treatment. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Kluiver, H.; Jansen, R.; Milaneschi, Y.; Bot, M.; Giltay, E.J.; Schoevers, R.; Penninx, B.W. Metabolomic profiles discriminating anxiety from depression. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2021, 144, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittelstraß, K.; Waldenberger, M. DNA methylation in human lipid metabolism and related diseases. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2018, 29, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, K.; Molina-Márquez, A.M.; Saavedra, N.; Zambrano, T.; Salazar, L.A. Epigenetic Modifications of Major Depressive Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, M.M.; Berry, O.O.; Warner, V.; Gameroff, M.J.; Skipper, J.; Talati, A.; Pilowsky, D.J.; Wickramaratne, P. A 30-Year Study of 3 Generations at High Risk and Low Risk for Depression. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musliner, K.L.; Trabjerg, B.B.; Waltoft, B.L.; Laursen, T.M.; Mortensen, P.B.; Zandi, P.P.; Munk-Olsen, T. Parental history of psychiatric diagnoses and unipolar depression: A Danish National Register-based cohort study. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 2781–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluharty, M.; Taylor, A.E.; Grabski, M.; Munafò, M.R. The Association of Cigarette Smoking with Depression and Anxiety: A Systematic Review. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2017, 19, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Meng, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, S. Serum HDL mediates the association between inflammatory predictors and depression risk after the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 387, 119525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsimani, P.; Montgomery, A.; Georganta, K. The Relationship Between Burnout, Depression, and Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcolongo-Pereira, C.; de Abreu Quintela Castro, F.C.; Barcelos, R.M.; Chiepe, K.C.M.B.; Rossoni Junior, J.V.; Ambrosio, R.P.; Chiarelli-Neto, O.; Pesarico, A.P. Neurobiological mechanisms of mood disorders: Stress vulnerability and resilience. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1006836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daviu, N.; Bruchas, M.R.; Moghaddam, B.; Sandi, C.; Beyeler, A. Neurobiological links between stress and anxiety. Neurobiol. Stress 2019, 11, 100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riera-Serra, P.; Navarra-Ventura, G.; Castro, A.; Gili, M.; Salazar-Cedillo, A.; Ricci-Cabello, I.; Roldán-Espínola, L.; Coronado-Simsic, V.; García-Toro, M.; Gómez-Juanes, R.; et al. Clinical predictors of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and suicide death in depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 274, 1543–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trindade Júnior, S.C.; Sousa LFFde Carreira, L.B. Generalized anxiety disorder and prevalence of suicide risk among medical students. Rev. Bras. Educ. Médica 2021, 45, e061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiebenga, J.X.M.; Dickhoff, J.; Mérelle, S.Y.M.; Eikelenboom, M.; Heering, H.D.; Gilissen, R.; van Oppen, P.; Penninx, B.W. Prevalence, course, and determinants of suicide ideation and attempts in patients with a depressive and/or anxiety disorder: A review of NESDA findings. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 283, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, G.; Baldassarre, I.; Barbaro, A.; Cavallo, N.D.; Cropano, M.; Nappo, R.; Santangelo, G. Age- and gender-related differences in the evolution of psychological and cognitive status after the lockdown for the COVID-19 outbreak: A follow-up study. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 43, 1521–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, K.N.; Hübel, C.; Cheesman, R.; Adey, B.N.; Armour, C.; Davies, M.R.; Hotopf, M.; Jones, I.R.; Kalsi, G.; McIntosh, A.M.; et al. Age and sex-related variability in the presentation of generalized anxiety and depression symptoms. Depress. Anxiety 2021, 38, 1054–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrós, F.; Pintor-Sánchez, B.E. Estructura interna y confiabilidad del BDI (Beck Depression Inventory) en universitarios de Michoacán (México). Psicodebate 2021, 21, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, O.; Teixeira, L.; Araújo, L.; Rodríguez-Blázquez, C.; Calderón-Larrañaga, A.; Forjaz, M.J. Anxiety, Depression and Quality of Life in Older Adults: Trajectories of Influence across Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, M.; Visier, M.E.; Silvestre, I.N.; Navarro, B.; Serrano, J.P.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Relation between resilience and personality traits: The role of hopelessness and age. Scand. J. Psychol. 2023, 64, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, J.E.; Han, L.K.M.; Lever-van Milligen, B.A.; Hu, M.X.; Révész, D.; Hoogendoorn, A.W.; Batelaan, N.M.; van Schaik, D.J.; van Balkom, A.J.; van Oppen, P.; et al. Antidepressants or running therapy: Comparing effects on mental and physical health in patients with depression and anxiety disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 329, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szuhany, K.L.; Bugatti, M.; Otto, M.W. A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 60, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Cunha, L.L.; Feter, N.; Alt, R.; Rombaldi, A.J. Effects of exercise training on inflammatory, neurotrophic and immunological markers and neurotransmitters in people with depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 326, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, M.N.; Deuster, P.A. Biological mechanisms underlying the role of physical fitness in health and resilience. Interface Focus 2014, 4, 20140040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, A.; Edirappuli, S.; Pedersen, H.; Zaman, R. The effect of exercise on mental health: A focus on inflammatory mechanisms. Psychiatr. Danub. 2020, 32, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carrera-Bastos, P.; Bottino, B.; Stults-Kolehmainen, M.; Schuch, F.B.; Mata-Ordoñez, F.; Müller, P.T.; Blanco, J.-R.; Boullosa, D. Inflammation and depression: An evolutionary framework for the role of physical activity and exercise. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1554062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigutytė, N.; Mikuličiūtė, V.; Petraškaitė, K.; Kairys, A. Beck Scales (BDI-II, BAI, BHS, BSS, and CBOCI): Clinical and Normative Samples’ Comparison and Determination of Clinically Relevant Cutoffs. Psichologija 2022, 67, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auvinen, J.; Korpelainen, R.; Lankila, T.; Miettunen, J.; Seppänen, M.; Timonen, M. Cross-cultural comparison of depressive symptoms on the Beck Depression Inventory-II, across six population samples. BJPsych Open 2022, 8, e46. [Google Scholar]

- do Nascimento, R.L.; Fajardo-Bullon, F.; Santos, E.; Landeira-Fernandez, J.; Anunciação, L. Psychometric Properties and Cross-Cultural Invariance of the Beck Depression Inventory-II and Beck Anxiety Inventory among a Representative Sample of Spanish, Portuguese, and Brazilian Undergraduate Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Bi, K.; Yip, P.S.F.; Cerel, J.; Brown, T.T.; Peng, Y.; Pathak, J.; Mann, J.J. Decoding Suicide Decedent Profiles and Signs of Suicidal Intent Using Latent Class Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2024, 81, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.