Bullying and Harassment in a University Context: Impact on the Mental Health of Medical Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

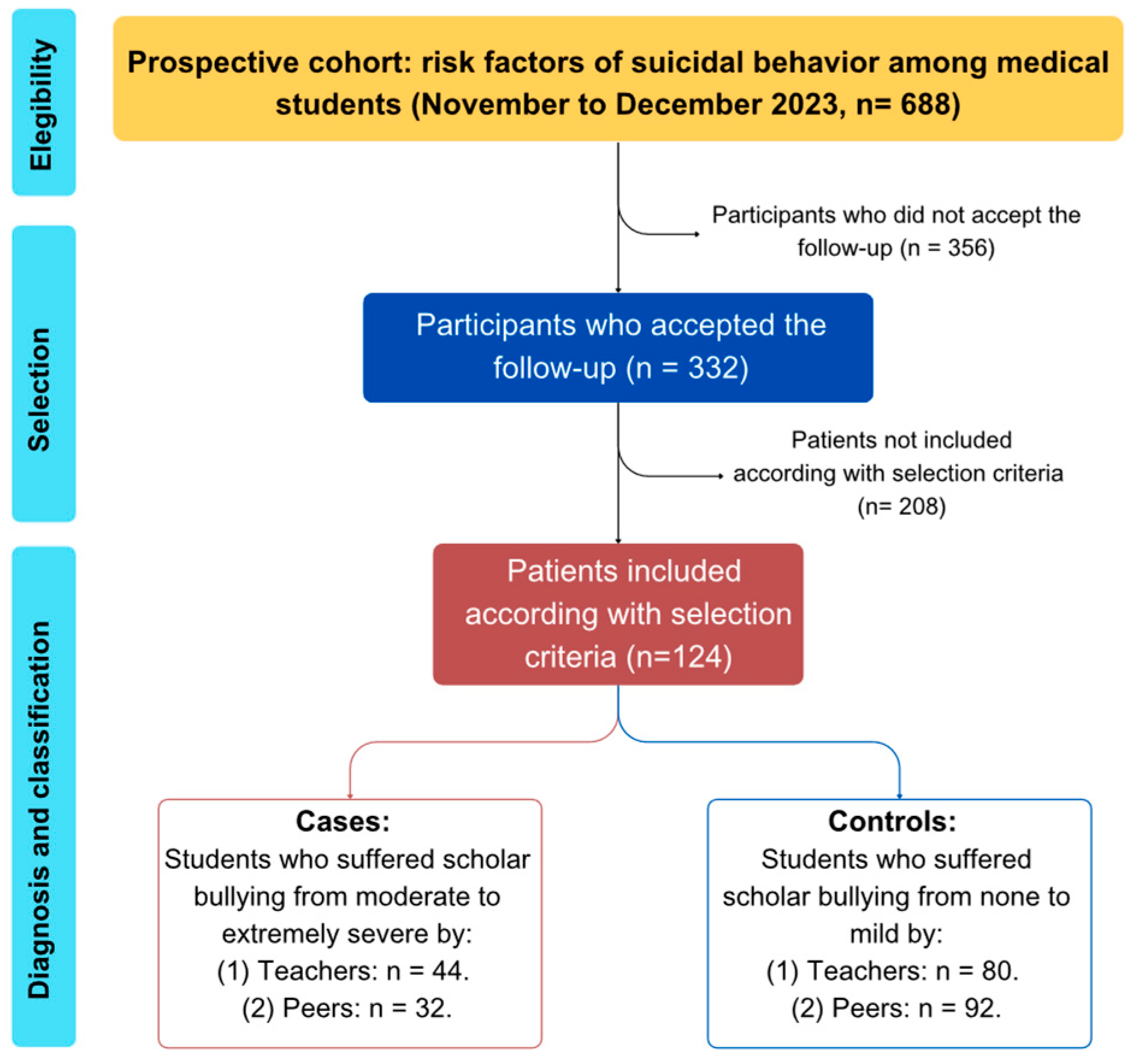

2.2. Study Design and Participants

2.3. Instruments for Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Study Population

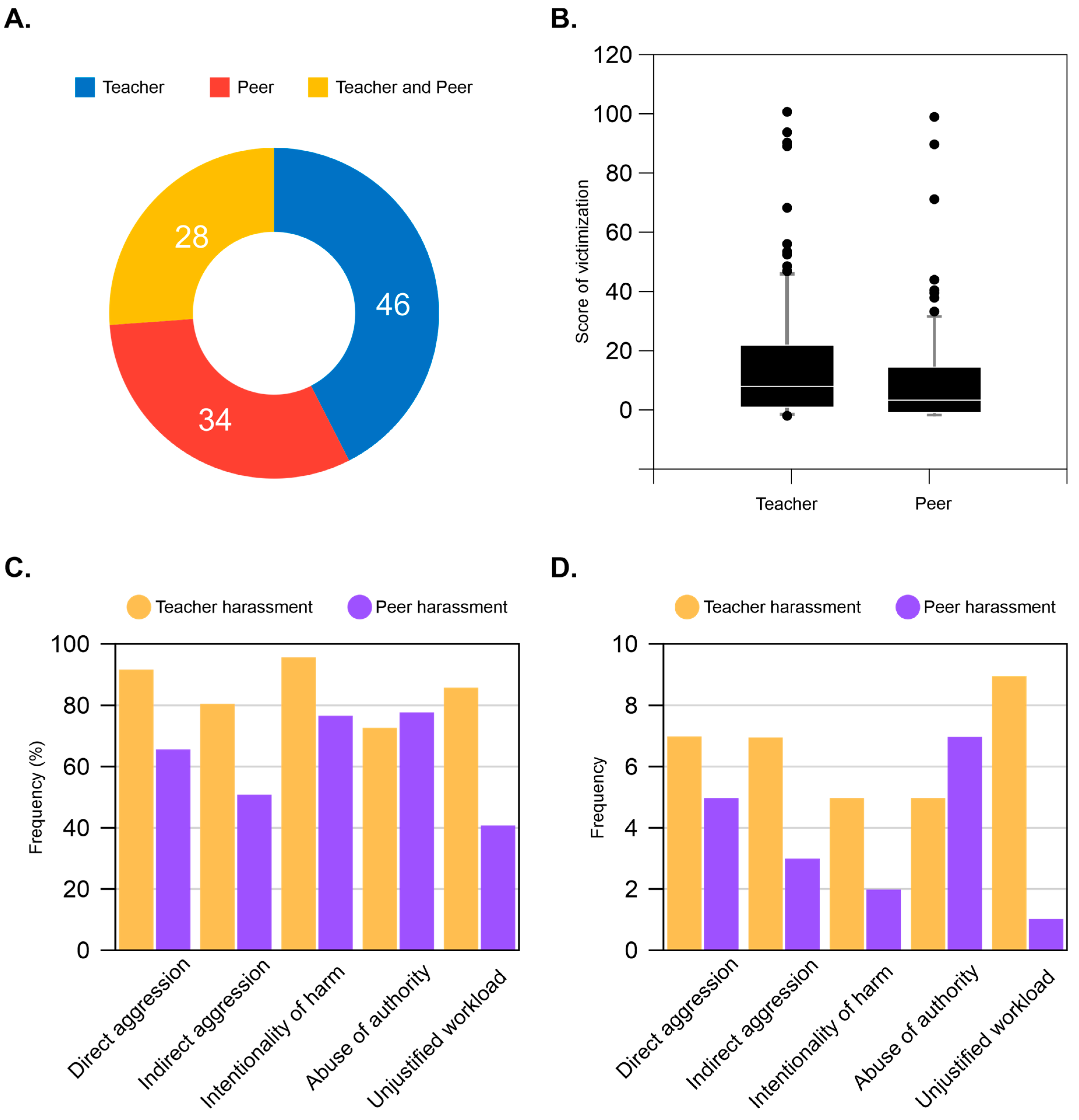

3.2. Distribution of Scholar Harassment Profiles

3.3. Bivariate Analysis of Harassment

3.3.1. Mental Disorders and Their Association with Academic Harassment

3.3.2. Suicidal Behavior and Academic Harassment

3.3.3. Academic Bullying and Drugs and Substances Use

3.3.4. Correlations Between Academic Harassment and Symptoms of Mental Health Disorders

3.4. Multivariate Regression Analyses: Predictors of Teacher and Peer Harassment

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations for Medical School Governance and Training Environments: Translating Findings into Practice

4.2. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Plata Santander, J.V.; Romero Palencia, A.; del Castillo Arreola, A.; Domínguez Aguirre, G.Á.; Martínez Peralta, A. Validación del inventario multidimensional de acoso psicológico en universitarios. Psicol. Iberoam. 2015, 23, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Morales, J. Acoso escolar. Rev. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2013, 74, 224–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puga Brito, A.D.J. El acoso escolar y su relación con factores psicosociales en estudiantes de Psicología de la Universidad La Salle México. Mem. Concurs. Lasallista Investig. Desarro. Innovación 2024, 11, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, I.; Ruiz-Esteban, C.; Martínez Ramón, J.P.; Cerezo, F. Acoso escolar en el ámbito universitario. Behav. Psychol. 2019, 27, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Romero Palencia, A.; Plata Santander, J.V. Acoso escolar en universidades. Enseñanza Investig. Psicol. 2015, 20, 266–274. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Los Países se Comprometen a Tomar Medidas Para Poner fin a la Violencia Que Afecta a Casi Mil Millones de Niños. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news/item/07-11-2024-countries-pledge-to-act-on-childhood-violence-affecting--some-1-billion-children (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- OECD. Nurturing Social and Emotional Learning Across the Globe: Findings from the OECD Survey on Social and Emotional Skills 2023; OECD: París, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleyshaw, L. The power of paradigms: A discussion of the absence of bullying research in the context of the university student experience. Res. Post-Compuls. Educ. 2010, 15, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Osorio, J.-F.; Arias-Gómez, M.-C. Acoso escolar contra jóvenes LGBT e implicaciones desde una perspectiva de salud. Rev. Univ. Ind. Santander. Salud 2020, 52, 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- i Caralt, J.C.; Miquel, C.E. El acoso escolar: Un enfoque psicopatológico. Anu. Psicol. Clín. Salud. Annu. Clin. Health Psychol. 2006, 2, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Fondevila, G. Freezing Out the Mexican Cops: Bullying as Discrimination at the Police Workplace in Mexico City. Int. J. Criminol. Sociol. 2013, 2, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Badillo, A.; Torres Cruz, M.d.L. Emotional indicators associated with bullying behaviors victimization. Int. J. Innov. Educ. Res. 2020, 8, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafi, R.R.; Labib, N.I.; Islam, F.; Sulatana, R.; Rokonuzzaman; Hasan, M.M.; Ety, A.S.; Jannat, N.; Nabin, K.M.; Al Amin, M.; et al. Bullying in University Students: Examining the Effects on Mental Health and Academic Success. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda-Vildosola, A.C.; Mota-Nova, A.R.; Fajardo-Dolci, G.E.; Reyes-Lagunes, L.I. Workplace bullying during specialty training in a pediatric hospital in Mexico: A little-noticed phenomenon. Rev. Médica Inst. Mex. Seguro Soc. 2017, 55, S92–S101. [Google Scholar]

- Carrard, V.; Berney, S.; Bourquin, C.; Ranjbar, S.; Castelao, E.; Schlegel, K.; Gaume, J.; Bart, P.A.; Schmid Mast, M.; Preisig, M.; et al. Mental health and burnout during medical school: Longitudinal evolution and covariates. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0295100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo-Rasmussen, C.A.; Ramirez-Lopez, G.; Rajmil, L.; Skalicky, A.; Martin, A.H. Bullying and health-related quality of life in children and adolescent Mexican students. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2018, 23, 2433–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, Y.; Acuña, J. Acoso escolar y disrupción del aprendizaje en estudiantes de la secundaria de Chilpancingo, México. Rev. Innova Educ. 2020, 2, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Gutierrez, J.L. Discipline or workplace bullying? Rev. Médica Inst. Mex. Seguro Soc. 2020, 58, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Avila-Carrasco, L.; Diaz-Avila, D.L.; Reyes-Lopez, A.; Monarrez-Espino, J.; Garza-Veloz, I.; Velasco-Elizondo, P.; Vazquez-Reyes, S.; Mauricio-Gonzalez, A.; Solis-Galvan, J.A.; Martinez-Fierro, M.L. Anxiety, depression, and academic stress among medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1066673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Fierro, M.L.; Reyes-Hurtado, J.R.; Ayala-Haro, A.E.; Avila-Carrasco, L.; Ramirez-Hernandez, L.A.; Lozano-Razo, G.; Zavala-Rayas, J.; Vazquez-Reyes, S.; Mauricio-Gonzalez, A.; Velasco-Elizondo, P.; et al. The hidden risk factors behind of suicidal behavior in medical students: A cross-sectional cohort study in Mexico. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1505088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez Villalobos, N.A.; De Leon Gutierrez, H.; Ruiz Hernandez, F.G.; Elizondo Omana, G.G.; Vaquera Alfaro, H.A.; Carranza Guzman, F.J. Prevalence and associated factors of bullying in medical residents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Occup. Health 2023, 65, e12418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, H.K.; Glicken, A.D. Medical Student Abuse: Incidence, Severity, and Significance. JAMA 1990, 263, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averbuch, T.; Eliya, Y.; Van Spall, H.G.C. Systematic review of academic bullying in medical settings: Dynamics and consequences. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, N.C. Interrelación entre el trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad y el acoso escolar. DOCRIM Rev. Científica 2025, 19, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Medina Morales, E.L. El Acoso Escolar y su Influencia en el Bajo Rendimiento Académico en Los Estudiantes del Décimo año de Educación Básica; Universidad Estatal Península de Santa Elena: La Libertad, Ecuador, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Colenbrander, L.; Causer, L.; Haire, B. ‘If you can’t make it, you’re not tough enough to do medicine’: A qualitative study of Sydney-based medical students’ experiences of bullying and harassment in clinical settings. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, M.A.; Stonyer, J.; Chen, Y.; Hove, B.A.; Moir, F.; Webster, C.S. Medical Students’ Experience of Harassment and Its Impact on Quality of Life: A Scoping Review. Med. Sci. Educ. 2021, 31, 1487–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carranza, Z.N.S.; Alvarado, C.I.L.; Tapia, J.C.V. Impacto de la orientación psicológica enfocada al entorno socio-familiar, para disminuir consumo de sustancias psicotrópicas en estudiantes: Impact of psychological guidance focused on the socio-family environment, to reduce consumption of psychotropic substances in students. Boletín Científico Ideas y Voces 2024, 4, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Erazo, J.L. Estrategias de prevención y control del microtráfico en entornos escolares. Aula Virtual 2024, 5, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Mendez, K.G.; Bonilla Grajales, D.A.; Bolaños Forero, B.F. Violencia Escolar en Colegios Públicos de la Localidad de Kennedy; Universidad EAN: Bogotá, Colombia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitterman, A.; Hess, D.B. Understanding Generation Gaps in LGBTQ+ Communities: Perspectives About Gay Neighborhoods Among Heteronormative and Homonormative Generational Cohorts. In The Life and Afterlife of Gay Neighborhoods: Renaissance and Resurgence; Bitterman, A., Hess, D.B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 307–338. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.; Cheng, S.; Liu, W.; Ma, J.; Sun, W.; Xiao, W.; Liu, J.; Thai, T.T.; Al Shawi, A.F.; Zhang, D.; et al. Gender differences in the associations of adverse childhood experiences with depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 378, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total (n = 124) | Teacher Harassment | p-Value | Peer Harassment | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n = 44) | Controls (n = 80) | Cases (n = 32) | Controls (n = 92) | ||||

| Age | 20.8 ± 3.28 | 20.9 ± 4.04 | 20.7 ± 2.79 | 0.589 | 21.22 ± 3.210 | 20.70 ±3.31 | 0.500 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 77 (62) | 25 (57) | 52 (65) | 0.481 | 19 (59) | 58 (63) | 0.875 |

| Male | 47 (38) | 19 (43) | 28 (35) | 13 (41) | 34 (37) | ||

| Gender identity | |||||||

| Cisgender | 118 (95) | 41(93) | 77 (96) | 0.746 | 29 (91) | 89 (97) | 0.363 |

| Another | 6 (5) | 3 (7) | 3 (4) | 3 (9) | 3 (3) | ||

| Sexual orientation | |||||||

| Heterosexual | 92 (74) | 26 (59) | 66 (82.5) | 0.008 * | 21 (66) | 71 (77) | 0.293 |

| Another | 32 (26) | 18 (41) | 14 (17.5) | 11 (34) | 21 (23) | ||

| Marital status | |||||||

| With couple | 5 (4) | 3 (7) | 2 (2.5) | 0.489 | 3 (9) | 2 (2) | 0.207 |

| Without a couple | 119 (96) | 41 (93) | 78 (97.5) | 29 (91) | 90 (98) | ||

| Foreigner | |||||||

| Yes | 58 (47) | 22 (50) | 36 (45) | 0.730 | 17 (53) | 41 (45) | 0.529 |

| No | 66 (53) | 22 (50) | 44 (55) | 15 (47) | 51 (55) | ||

| Social class | |||||||

| Upper middle class | 19 (15.3) | 5 (11) | 14 (17) | 0.086 | 3 (9) | 16 (17) | 0.658 |

| Middle class | 57 (46) | 18 (41) | 39 (49) | 15 (47) | 42 (46) | ||

| Lower middle class | 45 (36.3) | 18 (41) | 27 (34) | 13 (41) | 32 (35) | ||

| Poverty | 3 (2.4) | 3 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 2 (2) | ||

| Mental disorder | |||||||

| Yes | 64 (52) | 26 (59) | 38 (47.5) | 0.295 | 22 (69) | 42 (46) | 0.041 * |

| No | 60 (48) | 18 (41) | 42 (52.5) | 10 (31) | 50 (54) | ||

| Mental health care | |||||||

| Yes | 50 (40) | 22 (50) | 28 (35) | 0.151 | 13 (41) | 37 (40) | 0.866 |

| No | 74 (60) | 22 (50) | 52 (65) | 19 (59) | 55 (60 | ||

| Childhood trauma history | |||||||

| Yes | 70 (56.5) | 29 (66) | 41 (51) | 0.321 | 19 (59.4) | 51 (55) | 0.952 |

| I don’t know | 44 (35.5) | 12 (27) | 32 (40) | 11 (34.4) | 33 (36) | ||

| No | 10 (8) | 3 (7) | 7 (9) | 2 (6.2) | 8 (9) | ||

| Bullying | |||||||

| Yes | 92 (74) | 35 (79.5) | 57 (71) | 0.426 | 26 (81) | 66 (72) | 0.410 |

| No | 32 (26) | 9 (20.5) | 23 (29) | 6 (19) | 26 (28) | ||

| Sons | |||||||

| Yes | 2 (1.6) | 2 | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 0.109 | |

| No | 122 (98.4) | 42 | 80 (100) | 0.239 | 30 (94) | 92 (100) | |

| Working | |||||||

| Yes | 18 (14.5) | 5 (11) | 13 (16) | 0.637 | 3 (9) | 15 (16) | 0.505 |

| No | 106 (85.5) | 39 (89) | 67 (84) | 29 (91) | 77 (84) | ||

| Childhood abuse | |||||||

| Yes | 61 (49) | 28 (64) | 33 (41) | 0.028 * | 22 (69) | 39 (42) | 0.018 * |

| No/I don’t know | 63 (51) | 16 (36) | 47 (59) | 10 (31) | 53 (58) | ||

| Finding | Total (n = 124) | Teacher Harassment | p-Value | Peer Harassment | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n = 44) | Controls (n = 80) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Cases (n = 32) | Controls (n = 92) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | ||||

| ADHD | |||||||||

| Indicative | 101 (81) | 41 (93) | 60 (75) | 4.556 | 0.024 * | 31 (97) | 70 (76) | 9.743 | 0.019 * |

| Probable or unlikely | 23 (19) | 3 (7) | 20 (25) | (1.331–15.14) | 1 (3) | 22 (24) | (1.568–104.1) | ||

| Stress | |||||||||

| Extremely severe or severe | 69 (56) | 31 (70.5) | 38 (47.5) | 2.636 | 0.023 * | 25 (78) | 44 (48) | 3.896 | |

| Moderate to normal | 55 (44) | 13 (29.5) | 42 (52.5) | (1.242–5.774) | 7 (22) | 48 (52) | (1.597–9.724) | 0.006 * | |

| Anxiety | |||||||||

| Extremely severe or severe | 96 (77) | 38 (86) | 58 (72.5) | 2.402 | 0.123 | 27 (84) | 69 (75) | 1.8 | 0.397 |

| Moderate to normal | 28 (23) | 6 (14) | 22 (27.5) | (0.898–6.352) | 5 (16) | 23 (25) | (0.669–4.686) | ||

| Depression | |||||||||

| Extremely severe or severe | 88 (71) | 34 (77) | 54 (67.5) | 1.637 | 0.347 | 27 (84) | 61 (66) | 2.744 | |

| Moderate to normal | 36 (29) | 10 (23) | 26 (32.5) | (0.691–3.824) | 5 (16) | 31 (34) | (0.965–7.031) | 0.087 | |

| Impulsivity | |||||||||

| High impulsivity | 82 (66) | 31 (70.5) | 51 (64) | 1.356 | 0.578 | 27 (84) | 55 (60) | 3.633 | 0.021 * |

| Low impulsivity | 42 (34) | 13 (29.5) | 29 (36) | (0.622–3.013) | 5 (16) | 37 (40) | 1.300–9.242 | ||

| Suicide | |||||||||

| Treatment or assessment | 38 (31) | 18 (41) | 20 (25) | 2.077 | 0.102 | 16 (50) | 22 (24) | 3.182 | 0.011 * |

| Normal | 86 (69) | 26 (59) | 60 (75) | (0.902–4.700) | 16 (50) | 70 (76) | (1.379–7.487) | ||

| Variable | Total (n = 124) | Teacher Harassment | p-Value | Peer Harassment | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n = 44) | Controls (n = 80) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Cases (n = 32) | Controls (n = 92) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | ||||

| Alcohol | |||||||||

| Medium risk–addiction | 33 (27) | 13 (30) | 20 (25) | 1.258 (0.539–2.730) | 0.737 | 10 (31) | 23 (25) | 1.364 (0.548–3.259) | 0.648 |

| No consumption or low risk | 91 (73) | 31 (70) | 60 (75) | 22 (69) | 69 (75) | ||||

| Tobacco | |||||||||

| Medium risk | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0.000–16.360) | 0.761 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0.000–25.880) | 0.579 |

| No consumption or low risk | 123 (99) | 44 (100) | 79 (99) | 32 (100) | 91 (99) | ||||

| Cannabis | |||||||||

| Problematic use or addiction | 12 (10) | 6 (14) | 6 (7.5) | 1.947 (0.552–6.819) | 0.430 | 5 (16) | 7 (8) | 2.249 (0.729–7.278) | 0.330 |

| Not problematic use | 112 (90) | 38 (86) | 74 (92.5) | 27 (84) | 85 (92) | ||||

| Other Drugs | |||||||||

| Yes | 17 (14) | 11 (25) | 6 (7.5) | 4.111 (1.487–12.240) | 0.015 * | 6 (19) | 11 (12) | 1.699 (0.554–4.694) | 0.507 |

| No | 107 (86) | 33 (75) | 74 (92.5) | 26 (81) | 81 (88) | ||||

| Substances other than alcohol or tobacco | |||||||||

| Yes | 23 (19) | 13 (30) | 10 (12.5) | 2.935 (1.207–7.781) | 0.036 * | 8 (25) | 15 (16) | 1.711 (0.638–4.361) | 0.409 |

| No | 101 (81) | 31 (70) | 70 (87.5) | 24 (75) | 77 (84) | ||||

| Variable | Teacher Harassment | Peer Harassment | Depression | Anxiety | Suicide | Stress | ADHD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher harassment | — | 0.541 *** | 0.151 | 0.16 | 0.194 * | 0.275 ** | 0.154 |

| Peer harassment | — | — | 0.069 | 0.124 | 0.189 * | 0.213 * | 0.171 |

| Depression | — | — | — | 0.561 *** | 0.392 *** | 0.558 *** | 0.270 ** |

| Anxiety | — | — | — | — | 0.335 *** | 0.555 *** | 0.216 * |

| Suicide | — | — | — | — | — | 0.308 *** | 0.225 * |

| Stress | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.422 *** |

| ADHD | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Harassment | Variable | Multiple Lineal Regression | Multiple Logistic Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (Coefficient) | p-Value | Odds Ratio | p-Value | 95% CI | ||

| Teacher | Childhood abuse | 8.766 | 0.020 * | 2.136 | 0.077 | 0.923–4.864 |

| ADHD | 3.891 | 0.444 | 3.302 | 0.084 | 0.847–13.75 | |

| Stress | 8.607 | 0.029 * | 1.941 | 0.136 | 0.808–4.767 | |

| Sexual orientation: | ||||||

| Other | 9.094 | 0.029 * | 6.765 | 0.003 * | 1.582–9.848 | |

| Peer | Childhood abuse | 0.137 | 0.086 | 2.309 | 0.083 | 0.895–5.954 |

| ADHD | 0.077 | 0.472 | 3.907 | 0.217 | 0.448–34.03 | |

| Impulsivity | 0.151 | 0.082 | 2.783 | 0.078 | 0.891–8.689 | |

| Stress | 0.115 | 0.166 | 2.061 | 0.164 | 0.744–5.708 | |

| Suicide | 0.133 | 0.126 | 1.926 | 0.168 | 0.758–4.896 | |

| Type of Harassment | Most Frequent Forms (%) | Main Associated Mental Health Factors | Predictors | Relevant Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher harassment | Intentional harm (78%), Direct aggression (74%), Unjustified workload (69%), Abuse of authority (59%) | Severe stress, ADHD, Substance use | Childhood abuse, Non-heterosexual orientation | OR = 2.94–4.11 (substance use); OR = 6.77 (non-heterosexual orientation); β = 8.77 (childhood abuse) |

| Peer harassment | Abuse of authority (63%), Intentional harm (62%), Indirect aggression (41%), Unjustified workload (33%) | Stress, Impulsivity, Suicide risk | Childhood abuse (trend), Impulsivity | OR = 3.90 (stress); OR = 3.63 (impulsivity); OR = 3.18 (suicide risk) |

| Shared context | Teacher–peer overlap (r = 0.541, p < 1 × 10−10) | Emotional distress, Self-harming ideation | — | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Martinez-Fierro, M.L.; Avila-Carrasco, L.; Basconcelos-Sanchez, J.M.; Peralta-Trejo, I.; Ortiz-Castro, Y.; Luna-Morales, M.E.; Ramirez-Hernandez, L.A.; Martinez-Vazquez, M.C.; Mentali Mental Health Collaborative Network; Garza-Veloz, I. Bullying and Harassment in a University Context: Impact on the Mental Health of Medical Students. Psychiatry Int. 2026, 7, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010008

Martinez-Fierro ML, Avila-Carrasco L, Basconcelos-Sanchez JM, Peralta-Trejo I, Ortiz-Castro Y, Luna-Morales ME, Ramirez-Hernandez LA, Martinez-Vazquez MC, Mentali Mental Health Collaborative Network, Garza-Veloz I. Bullying and Harassment in a University Context: Impact on the Mental Health of Medical Students. Psychiatry International. 2026; 7(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartinez-Fierro, Margarita L., Lorena Avila-Carrasco, Joselin M. Basconcelos-Sanchez, Isabel Peralta-Trejo, Yolanda Ortiz-Castro, María Elena Luna-Morales, Leticia A. Ramirez-Hernandez, Maria C. Martinez-Vazquez, Mentali Mental Health Collaborative Network, and Idalia Garza-Veloz. 2026. "Bullying and Harassment in a University Context: Impact on the Mental Health of Medical Students" Psychiatry International 7, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010008

APA StyleMartinez-Fierro, M. L., Avila-Carrasco, L., Basconcelos-Sanchez, J. M., Peralta-Trejo, I., Ortiz-Castro, Y., Luna-Morales, M. E., Ramirez-Hernandez, L. A., Martinez-Vazquez, M. C., Mentali Mental Health Collaborative Network, & Garza-Veloz, I. (2026). Bullying and Harassment in a University Context: Impact on the Mental Health of Medical Students. Psychiatry International, 7(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint7010008