Abstract

Numerous studies have investigated the relationship between autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and the use of Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART). However, the results have been inconclusive. This review aims to explore this association via the meta-analysis of existing studies. PubMed, Web of Knowledge, SCOPUS, and Embase databases were searched up to December 2023. Risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using random or fixed effect models to explore the association between ART and ASD. A total of 20 records of cohort and case–control studies were analyzed and diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) published between 2013 and 2023. Children between the ages of 2–12 years were included in these studies via a census method. The results of the studies revealed a significant correlation between ART and ASD (RR = 1.43, 95% CI: 1.13–1.71, p = 0.006). Some subgroups revealed statistically significant relationships based on study location, design, and quality. The results suggest that using assisted reproductive technology elevates the susceptibility of children to develop ASD, but more large-scale and prospective studies are required to corroborate this conclusion, particularly in light of the divergent outcomes of some reviewed studies.

1. Introduction

Numerous obstetric conditions have been linked to an increased risk of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). These include pregnancy age, perinatal and parental factors, early overgrowth, cesarean sections, infections during pregnancy, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, preterm delivery, and low birth weight [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. ASD is a developmental disorder marked by repetitive and restricted patterns in speech, social interaction, and behavior. Despite extensive attempts to manage ASD through care systems and therapy, it continues to be a serious public health concern around the world [11,12]. The prevalence of ASD has risen dramatically in the last decade, with its causes remaining unclear. In an attempt to identify possible contributing factors, recent studies have suggested a complex interplay of genetic and environmental variables [3,4,5,7,8,13], with ART (Assisted Reproductive Technology) frequently mentioned as a potential cause due to its widespread use [14]. In fact, studies describe a number of possible ways through which ART can be associated with ASD, including biological aspects (e.g., maternal fertility, the quality of the germ cells), hormone treatments administered during ART, additional ART side effects, and neonatal and prenatal problems associated with ART treatment [15].

The demand for ART, a broad term that encompasses therapies such as ZIFT (zygote intrafallopian transfer), GIFT (gamete intrafallopian transfer), ICSI (intra-cytoplasm sperm injection), IVF (in vitro fertilization), and artificial insemination, has dramatically grown in recent decades [16]. Consequently, there is a rising concern among experts regarding the developmental outcomes of pregnancies that result from treatment. According to recent evidence, utilizing ART was found to increase the incidence of congenital abnormalities by 33% and double the risk of nervous system disorders in offspring [17]. These abnormalities, in turn, may contribute to the development of ASD among children. While many epidemiological and observational studies have been conducted to investigate the relationship between ART use and the risk of ASD in children, the results have been inconsistent [18]. Conti et al. [19], for example, conducted a systematic analysis that reported no significant link between ART and ASD. On the other hand, researchers have indicated that male infertility problems and the use of intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) may increase the risk of ASD development in offspring. Other studies and meta-analyses found positive relationships between the utilization of ART and the development of ASD among children, albeit not always statistically significant [20,21].

Given the discrepancy of these findings, recognizing the potential link between ART and ASD is critical in order to plan and implement preventive steps with regard to the development of ART among children [22]. Additionally, further research that includes recent and contemporary studies is necessary to determine the significance of the hypothesized relationship between ART and ASD [23]. Therefore, this study aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of recent evidence that explored the relationships and association between ART and ASD.

2. Materials and Methods

The following criteria were used for the meta-analysis and systematic review protocol.

2.1. Search Strategy

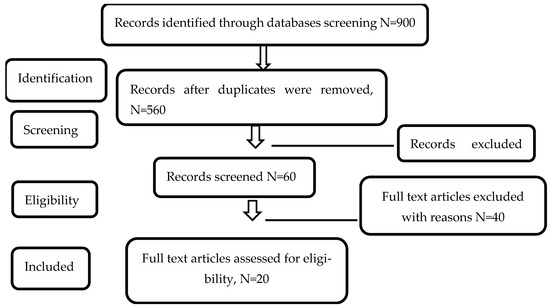

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) statement. The completed PRISMA diagram is provided in Figure 1 The PRISMA checklist can be found in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1) [23]. Databases such as Embase, PubMed, SCOPUS, and Web of Science were searched for relevant articles using the following keywords: “autism spectrum disorder” OR “Asperger syndrome” OR “pervasive development disorder” OR “autistic” AND “infertility” OR “oocytes” OR “assisted reproductive technology” OR “fertilization” OR “in vitro fertilization” OR “intra-cytoplasm sperm injection”. The search process concluded on 31 December 2023. Three separate researchers have contributed to the literature search process. The inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in Section 2.2.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included studies according to PRISMA Guidelines [23].

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The publications considered in this analysis fulfilled 3 criteria:

- (1)

- Scope: Studies that explored the relationship between ASD and ART usage.

- (2)

- Population: Studies including children under 18 years of age diagnosed with ASD using validated diagnostic methods including: (1) International Classification of Diseases codes (ICD-8, ICD-9, ICD-10), (2) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual criteria (DSM-III, DSM-IV), (3) standardized screening tools such as the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-Chat) or Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), (4) structured diagnostic interviews such as the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R), or national health or disability registries with validated ASD case definitions. Studies that included mothers of children with ASD or the children themselves as participants were also included.

- (3)

- Type: Cohort or case–control studies.

- (4)

- Results reporting: Studies that provided data that allowed for effect estimation.

Articles were excluded if they were found to not have sufficient data to derive impact estimates, had overlapping samples or sample sizes, or were found to be case-reports, animal studies, or reviews.

2.3. Evaluation of Study Quality

Three independent reviewers to assess the quality of research that met the inclusion criteria used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. The scale comprises three sections: “selection,” “comparability,” and “exposure or outcome,” for both case–control and cohort studies. The quality of the studies was assessed using a 9-star scale based on 8 elements. A study was judged high quality if it received 7 or more stars, whereas those receiving 4 to 6 stars and 0 to 3 stars were rated moderate and low quality, respectively. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) among the three reviewers was 0.73 (95% CI: 0.65–0.81), indicating good agreement. The mean absolute difference in total quality scores between reviewers was 1.2 points (SD = 0.9, range: 0–3 points). Most discrepancies occurred in the assessment of comparability and exposure/outcome categories. Disagreements that arose during the study evaluation phase were resolved via discussion consensus among team members, and final quality scores were assigned to each study.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was the main indicator of the relationship between Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) and Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) in this meta-analysis. The Z-test was used to determine the combined relative risk’s statistical significance. The degree of heterogeneity among the included studies, as assessed by the Q-test and the I2 statistic, provided the basis for choosing between fixed and random effects models. Where the heterogeneity was found to be low, the fixed effects model’s assumption was deemed appropriate. However, a random effects model was utilized to account for between-study variation when sufficient heterogeneity was identified (I2 > 50%, p < 0.05). The random effects model was mainly employed for the overall analysis to provide conservative estimates that account for potential changes between studies because of the high level of heterogeneity reported (I2 = 87.9%).

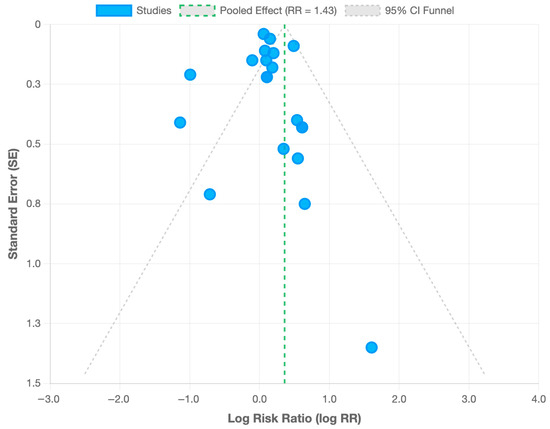

Subgroup analyses were carried out according to the studies’ design (cohort vs. case–control), geography (Asia, Europe, and America), study quality, and relevant confounding variables (e.g., maternal age, parity, and multiple births). These analyses facilitated the process of identifying and evaluating the impact of methodological variances or population-specific differences on the association between ART and ASD. To evaluate publication bias, Egger’s test was performed, which yielded insignificant results (p-value > 0.05). Additionally, a funnel’s plot was created to provide visual evidence of the publication bias examination (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Funnel plot for publication bias assessment. Each point represents one of the 20 included studies. The vertical line indicates the pooled risk ratio (RR = 1.43), and the diagonal dashed lines represent the 95% CI.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to ensure the rigor and robustness of the meta-analysis. Individual studies were gradually eliminated to ascertain whether any one study had a disproportionate impact on the overall outcomes. The pooled risk estimates were largely unchanged when individual studies were excluded, suggesting that the results were consistent and not overly reliant on any single study. Throughout the analyses, a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. STATA version 16 (College Station, TX, USA) and RevMan software version 5.4 (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020) were used for statistical analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Qualified Studies

The search process returned 900 records. There were 159 PubMed records, 320 Embase records, 220 Web of Science records, and 201 SCOPUS records. After removing 340 duplicate records and 500 irrelevant records, a total of 60 screened records were found eligible for full-text screening. A total of 40 studies were removed following the full-text screening process, resulting in 20 full text articles moving into the extraction and reliability assessment stage. The elimination of the 40 studies was due to these studies falling in the exclusion criteria. Figure 2 depicts the flow diagram.

The studies included covered in this analysis were carried out between 2006 and 2023. Six of these investigations were conducted in Asia, six in Europe, and eight in America. The trials included a total of 12,658,089 patients, of which 1,969,963 had ASD, accounting for 15.56% of the total population screened. The estimated effects were derived from the original data and modified for five studies. According to the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, twelve studies were found to be of high quality, four were evaluated as moderate, and four were evaluated as having low quality. In the reviewed studies, ASD was diagnosed using international coding and clinical examination. Two of the included studies were conducted in Europe, three in Asia, and three in America. The following tables summarize the characteristics and qualities of the studies included in this meta-analysis. Table 1 includes information such as study design, sample size, methodology, and outcome measures.

3.2. Data Synthesis (Quantitative)

The overall pooled risk ratio (RR) reported among children in the reviewed studies was (RR = 0.49–1.84, CI (95%): 0.04–1.18, 1.30–5.61, p = 0.059). In addition, six cohort studies during the interval between 1969 and 2009 investigated the prevalence of ASD in America and Europe, revealing that the pooled risk ratio (RR) of ASD in children was 1.20–1.71 (CI (95%): 0.90–1.89, p = 0.131).

In terms of the studies’ quality and pooled RR of ASD, the high quality studies reported a pooled risk ratio (RR) for ASD of (RR = 1.11, CI (95%): 1.03–1.19) which adjusted for confounders. Additionally, when using subgroup analyses of cohort and case–control studies and adjusting for maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, parity, plurality, infant sex and year of birth, parental and maternal age, and baby sex, the pooled risk ratio (RR) of ASD in America was found to be (RR: 1.1, CI (95%): 0.83–1.49). Similarly, when adjusting for birth order, year of birth, maternal age at birth, sex, and parental history of mental order variables, the pooled risk ratio (RR) of ASD was found to be (RR = 1.06, CI (95%) = 0.99–1.14) in Europe.

Table 1.

Description and characteristics of the 20 included studies for the meta-analysis in the review.

Table 1.

Description and characteristics of the 20 included studies for the meta-analysis in the review.

| Country | SD | Study Period | Source of Study Population | Case/Control | ART Type | Outcome | RR (CI-95%) | Adjusted Factors | Quality (NOS Score) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Velez et al. [24] | ||||||||||

| NA | Ontario, Canada | Ch | 2006–2018 | All hospital live births at 24 or more gestational weeks. | 1,370,152 | IVF, ICSI | ASD | 1.16 (1.04–1.28) | Mother’s age, parity, rural residence, immigration status, income quintile, smoking, drug or alcohol abuse, pre-gestational diabetes, hypertension, or obesity, history of mental disease within 2 years before the expected date of pregnancy and 1.5 years after birth, and a history of maternal ASD | High |

| 2. Magdalena et al. [25] | ||||||||||

| ADOS | Silesia (south-western region of Poland) | CC | 2016–2017 | Survey among parents of children | 121/100 | ART | ASD | 0.32 (0.06–1.68) | Conception problems, assisted reproductive technique, use of oral contraception and its duration, history of pregnancies and miscarriages, pregnancy intervals, history of mental illness or chronic diseases in parents before pregnancy, and other diseases during the pregnancy period | High |

| 3. Jenabi et al. [26] | ||||||||||

| ADI-R | Hamadan (Iran) | CC | 10 September to 10 November 2019 | Questionnaire for women with ASD child aged 2–10 years and had medical records in the Hamadan Autism Community | 100/200 | ART | ASD | 4.98 (0.91–27.30) | Parents’ and child’s age, mother’s work, parity, history of preterm labor, type of delivery, mode of conception, cause of infertility, and use of ART | High |

| 4. Diop et al. [27] | ||||||||||

| ICD-9 | Massachusetts (USA) | Ch | 2004–2013 | Database linked with the Early Intervention program and participation data | 10,147 | IVF, ICSI, and frozen embryo transfer | ASD | 1.08 (0.89–1.31) | Parental demographics (age, education level, marital status, and nativity), parity, insurance, smoking, prenatal care, gender, delivery method, gestational chronic diseases, and breech presentation | High |

| 5. Lung et al. [28] | ||||||||||

| NA | Taiwan | Ch | All babies born in Taiwan from October 2003 to January 2004 | The Taiwan national birth cohort dataset (TBCS) | 20,095 | ART | ASD | 1.41 (0.44–4.47) | Parental education level, age, residence, using ART, child sex, single or twin, and being premature with a diagnosis of ASD at 66 months | High |

| 6. Kotelchuck et al. [29] | ||||||||||

| ICD-9 | Massachusetts (USA) | Ch | 2004–2010 | Three data systems: (1) the Society of Assisted Reproductive Technology Clinical Outcomes Reporting System (SART-CORS) clinical database; (2) the Massachusetts Pregnancy to Early Life Longitudinal (PELL) public health data system; and (3) the Massachusetts’ children’s special needs Early Intervention (EI) program data | 480,075 | ART | ASD | 1.10 (0.80–1.40) | Paternal age parity, prenatal care, smoking, delivery method, history of hypertension, obstetric or gynecologic disease, gender, and prematurity | High |

| 7. Svahn et al. [30] | ||||||||||

| ICD-8/ICD-10 | Denmark | Ch | 1969–2008 | Computerized civil registration system | 2058/2,410,663 | NA | ASD | 1.06 (0.99–1.14) | Birth order, year of birth, maternal age at birth, sex, and history of psychological disorder | High |

| 8. Kamowski-Shakibai et al. [21] | ||||||||||

| NA | USA | CC | NA | Children across the United States | 8/155 | ART | ASD | 1.73 (0.33–9.08) | NA | Low |

| 9. Kissin et al. [31] | ||||||||||

| DSM-IV/code 299.0 | USA | Ch | 1997–2006 | All live-born ART- conceived infants in California | 42,383 | IVF, ICSI | ASD | 1.71 (1.10–2.66) | Parents’ age at birth, maternal education level, race and background, number of earlier labors, delivery method, baby sex, variety, pregnancy age, birth weight, and birth year | High |

| 10. Fountain et al. [14] | ||||||||||

| DSM-IV/code 299.0 | USA | Ch | 1997–2007 | The California Birth Master Files for 1997–2007, the California DDS autism caseload records for 1997–2011, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National ART Surveillance System for live births for 1997–2007 | 31,243/5,529,810 | ART | ASD | 1.71 (1.56–1.89) | Gender of infant, birth year, mother’s education, and race | Moderate |

| 11. Lehti et al. [32] | ||||||||||

| ICD-9/ICD-10 | Finland | CC | 1991–2007 | The Finnish Hospital Discharge Register | 4164/16,582 | IVF | ASD | 0.9 (0.70–1.30) | Maternal age, gestational age, and parity | High |

| 12. Özbaran et al. [33] | ||||||||||

| DSM-IV/ADSI/ WISC-R | Turkey | CC | NA | The outpatient clinic of Psychiatry Department of EUSM | 3/67 | ART | Autism | 0.49 (0.04–5.61) | NA | Low |

| 13. Grether et al. [34] | ||||||||||

| ICD-9 | USA | CC | 1995–2002 | A KPNC facility | 349/1847 | NA | ASD | 1.11 (0.77–1.62) | Parental and maternal age, baby sex, birth year, maternal race and education level, gestational age, and birth facility | Moderate |

| 14. Sandin et al. [35] | ||||||||||

| ICD-9/ICD-10 | Sweden | Ch | 1982–2009 | Swedish national Registers | 6959/2,541,125 | IVF, ICSI | Autistic Disorder | 1.22 (1.01–1.49) | Age, sex, and birth year | High |

| 15. Lyall et al. [15] | ||||||||||

| ADI-R | USA | CC | 1989–2011 | Members in the Nurses’ health study II | 50/2529 | ART | ASD | 1.11 (0.77–1.62) | Parental and maternal age, birth order, race, age, and income | Moderate |

| 16. Shimada [36] | ||||||||||

| DSM-IV-TR | Japan | CC | 2006–2009 | General Population of Tokyo/University of Tokyo Hospital | 467/100,118 | IVF, ICSI | ASD | 1.84 (1.18–2.85) | NA | Low |

| 17. Zachor and Ben [37] | ||||||||||

| DSM-IV-TR | Israel | CC | 1995–2002 | Large Israel population from registry of infants in Rabin Medical Center | 285/53,080 | IVF, ICSI | ASD | 1.84 (1.18–2.85) | NA | Low |

| 18. Hvidtjørn et al. [38] | ||||||||||

| ICD-10 | Denmark | Ch | 1995–2007 | Danish Civil Registration System and Danish Psychiatric Central Register | 625/31,225 | ART with ICSI or without ICSI | ASD | 1.20 (0.90–1.61) | Maternal age, parity, birth weight, gestational age, and parental history of psychiatric disease | High |

| 19. Maimburg & Vaeth [39] | ||||||||||

| ICD 8/ICD 10 | Denmark | Ch | 1990–1999 | The Danish Psychiatric Central Register, Medical Birth Register and from the medical birth records collected from the Danish maternity wards | 473/473 | ART | ASD | 0.37 (0.14–0.98) | Mother’s age, and country of origin, parity, multiplicity, birth weight, gestational age, and birth defect | High |

| 20. Stein et al. [40] | ||||||||||

| ICD 8/DSM III/IV | Israel | CC | 1970–1998 | ALUT center of Tel Aviv | 206/152 | Infertility requiring medical intervention | ASD | 1.91 (0.94–3.88) | NA | Moderate |

CC = case–control, Ch = cohort, NA = not available, EUSM = EGE University School of Medicine, ASD = autism spectrum disorder, ART = assisting reproductive technology, IVF = in vitro fertilization, ICSI = intra-cytoplasm sperm injection, DDS = Department of Developmental Services.

The moderate quality studies included one study that took place in Europe, with a pooled risk ratio (RR) of ASD equaling 1.29 (CI (95%): 1.04–1.63), which adjusted for attained “age, sex, birth year, maternal age”, parity, sex, birth weight, gestational age and parental psychiatric history, smoking, and body mass index. In addition, three moderate quality studies were conducted in America using case–control and cohort analysis with a pooled ASD RR of 1.71 (CI (95%): 0.95, 5.49) which adjusted for gender of infant, birth year, mother’s education, race. Finally, the low-quality studies are found in Asia with an ASD pooled RR of 1.84 (CI (95%): 1.18–2.85), and in Europe with an ASD pooled RR of (CI (95%): 0.94–3.88).

In terms of the relationship between ASD and the utilization of ARD, all types of ART reported in the reviewed studies were found to be related with a greater pooled risk ratio of ASD in children of 1.43 (95% CI: 1.13–1.71, p = 0.006).

3.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

The data analysis revealed significant heterogeneity amongst the studies, as shown by a high I2 value of 87.9% and a p-value of 0.000. Consequently, a subgroup analysis based on study quality, geography, and design was conducted to identify the reasons of this heterogeneity among the studies. However, the sub-group analysis did not substantially reduce the studies’ heterogeneity. Therefore, a Galbraith plot was utilized as a second measure to identify potential outliers that may be contributing to the disproportionate variance between studies. Three studies were found to be outliers contributing to the between-study heterogeneity. These studies had standardized residuals exceeding ±2 standard deviations from the pooled effect estimate. After excluding these studies, the heterogeneity was reduced to an I2 of 30.97% with a p-value greater than 0.001. The corresponding pooled RR, however, was marginally adjusted to 1.14 with a CI (95%) of 1.05–1.39 and a p-value of 0.019. These results demonstrate that while the magnitude of the association was somewhat reduced after excluding outlier studies, the overall and statistical significance of the association between ART and ASD remain consistent, supporting the robustness of this review’s primary findings. A summary of the heterogeneity analysis in addition to all analyses conducted in this study can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of results of meta-analysis.

3.4. Study Design (Control vs. Cohort)

Cohort and case–control studies were used to group studies in order to determine whether study design had an impact on the relationship between ART and ASD. In case–control studies, the pooled relative risk (RR) was 1.37 (95% CI: 0.74–3.60). For cohort studies, the pooled relative risk was 1.29 (95% CI: 1.1–1.53).

3.5. Geographical Region (North America, Europe, and Asia)

The pooled RR for the studies conducted in Asia was 1.39 (95% CI: 0.8–3.77). For studies conducted in Europe and America, the pooled RR was 1.37 (95% CI: 1.01–1.98) and 1.34 (95% CI: 0.87–3.09), respectively. No statstically significant differences were noted between regions.

3.6. Study Quality (High, Moderate, Low)

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used to stratify studies according to their quality. Studies of moderate quality revealed a larger association between the utilization of ART and ASD (RR = 1.46; 95% CI: 1.0–3.17) than high-quality studies, which demonstrated a significant association (RR = 0.98; 95% CI: 0.75–1.95). Studies of lower quality reported a higher RR (1.63; 95% CI: 1.1–3.19).

3.7. Type of ART Procedure (ICSI vs. IVF)

Subgroup analyses for in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) were carried out. Research studies that reported using IVF as a standalone measure indicated a lower risk of ASD (RR = 1.28; 95% CI: 1.05–1.57) than those reporting results for ICSI (RR = 1.41; 95% CI: 1.13–1.85).

3.8. Parental Age

Children born to women 35 years of age or older had a significantly higher risk of ASD (RR = 1.35; 95% CI: 1.11–1.62) than children born to younger mothers, according to the subgroup analysis that was stratified by maternal and paternal age. Likewise, a higher risk was linked to advanced maternal age (>40) (RR = 1.29; 95% CI: 1.07–1.54).

3.9. Singleton Versus Multiple Births

ART pregnancies frequently result in multiple births, which have been associated with an increased incidence of ASD. The pooled RR for multiple births in this analysis was 1.43 (95% CI: 1.18–1.79), whereas the RR for singleton births was 1.22 (95% CI: 1.03–1.45).

4. Discussion

In this meta analysis, we aimed to address the scarcity of literature that examines the relationship between the use of ART and the likelihood of ASD in children. This study has several strengths. Firsly: the included studies comprise a large sample size of 12,658,089 patients, which is crucial to inform future interventions and policy development. Additionally, the use of quantitative analysis enhances the study’s statistical power, and results in more trustworthy estimates. Additionally, the subgroup analysis facilitated the process of identifying the most relevant moderators of heterogeneity to ensure the meta analysis methodological rigor.

The findings of this meta-analysis are consistent with the literature, which have revealed that ART use is associated with developmental delays, autism, and cerebral palsy in offspring [41]. One possible reason for this association is that the numerous phases that comprise ART techniques, such as sperm preparation, hormone exposure, usage of culture media, delayed insemination, freezing of gametes and embryos, and embryo growth conditions, may generate epigenetic alterations. Epigenetic factors, such as genetic imprinting abnormalities, have been proposed as potential contributors to a variety of neuropsychiatric illnesses, including Fragile X syndrome and Rett syndrome, which are characterized by autism-like symptoms in patients [35]. Melnyk et al. [42] suggested that aberrant methylation in ART imprinting problems may be related to ASD, and animal studies suggest that several ART methods, such as the in vitro cultivation of embryos or oocytes, superovulation, and IVF, may be associated with epigenetic deficits in embryos and offspring. However, further research is warranted to identify and describe the precise mechanism in which ART procedures may contribute to ASD development in children.

The subgroup analyses described in this meta-analysis offer insightful information about how different characteristics may impact the relationship between ART and ASD. For instance, the larger correlation shown with ICSI supports the hypothesis that more intrusive ART methods via epigenetic changes may contribute to increasing the chance of neurodevelopmental disorders, a trend that was also reported in Källén’s 2014 study of Swedish children [43]. In a similar vein, the increased risk in offspring of older parents emphasizes how crucial it is to take into account both ART-related variables and underlying parental traits when determining the risk of ASD.

In terms of the subgroup analysis related to location and study quality, the results of our study revealed a significant association between ART use and an elevated risk of ASD in children from Asian and European countries. This markedly weaker association in North American research may be due to differences in study design and ASD diagnosis criteria. The higher association observed in European populations may reflect differences in ART practices, population genetics, or environmental factors, such as nutritional practices, maternal diet, and prenatal supplmentation protocols. For instance, variations in folate metabolism and prescribing patterns have been identified as contributing factors to the neurodevelopmental outcomes of children [1]. Similarly, recent evidence suggests that targeted folinic acid supplementation during pregnancy may contribute to reducing ASD risk among women with folate receptor alpha autoantibodies [2]. Although such factors could contribute to the regional heterogeneity observed in our findings, the data available in the included studies were insufficient to allow for quantitative assessment of these effects. Future prospective, mechanistic research is warranted to explore these potential biochemical and environmental mediators in greater depth.

Certain environmental factors, such as parental infertility, maternal age, multiple births, and pre-term delivery have been found to be associated with the development of ASD in the reviewed studies. These factors were taken into account in all reviewed studies included in this meta-analysis. Various studies (7 in total) have also adjusted their estimates for variables such as birth year, maternal education, and infant gender. Only one of the studies included in this analysis, however, examined the relationship between maternal age and ASD. Children born to younger mothers had a lower risk of getting ASD than children born to mothers aged thirty-five years or older. Additional research is therefore required to investigate these differences.

Similarly, our study results suggest that multiple births and parental infertility were found to contribute to a higher risk of developing ASD in children. This finding is in line with established literature, as a study by Liu et al. [13] found a significant association between infertility drugs (in the general category) and ASD in multiple births, but not in singleton births. Our study investigated the exposure stratified by singleton and multiple births to compare the results of prior studies with those of this meta-analysis. Three of the eleven papers included in our meta-analysis conducted separate analyses for singleton babies and found no link between ASD and IVF in any subgroup. Meanwhile, two studies conducted separate analyses for the multiple-birth group and concluded that no statistically significant differences were found between the multiple-birth group and the singleton-birth group. The different conclusions that were identified in the literature may be reflective of the complex and multi-faceted nature of ASD development in children. In fact, some studies are suggesting that parental infertility itself is a major contributing factor of ASD development in children, rather than ART techniques. Hence, further research is needed to further explicate and describe the relationships, association mechanisms, and confounding variables that may regulate the relationships between ART and ASD.

Of note, some of the reviewed studies included in this meta-analysis have found contradictory results with regard to the hypothesized relationship between ART and ASD, indicating that ART has little to no effect on the ASD risk of children. This divergence may be attributed to the small sample sizes utilized in those studies. Furthermore, the conflicting results indicate the persistent lack of clarity in identifying and describing the exact biological processes that link ART with a higher risk of developing ASD. A possible explanation is the epigenetic changes brought about by ART techniques, such as ovarian stimulation, in vitro embryo culture, and gamete and embryo freezing, especially during crucial phases of embryonic development [44,45]. The literature indicates that alterations in epigenetics may impact the expression of genes related to neurodevelopment, which could elevate the likelihood of ASD [46,47].

This study is not without limitations. First, heterogeneity among the studies investigating the relationship between ART and ASD was identified, which may conceal the connection between ART and ASD. Three studies were identified as potential sources of heterogeneity, and excluding them from the analysis resulted in a more robust and consistent pooled RR. However, despite these measures, interpretations of the association between ART and ASD should be made with caution given this high heterogenity. Second, the included studies in the meta analysis were observational in nature, which, in turn warrants caution with regard to deriving causality conclusions using the results of the analysis.

Despite these limitations, this study’s results can be considered a building block for interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research projects. The results of this meta analysis, particularly those that highlight the divergence in available literature regarding the relationship between ART and ASD, highlight the necessity of systematic and more in-depth examination of ART technique specifics, parental demographics, and pregnancy outcomes in future research in order to enable more thorough subgroup analysis. Furthermore, when counseling prospective parents, particularly those having ICSI or older couples using ART, clinical practice should consider these risk factors. Future research that examines the association between ART and the relative risk of ASD development for each subtype of intervention is also necessary to identify the exact mechanisms in which each technique may be contribuitng to ASD. Additionally, future studies can investigate whether children with ASD born with assisted reproduction exhibit a different clinical phenotype in comparison to ASD children born without ART, with regard to factors like gender, psychiatric comorbidity, and the severity of ASD symptoms.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis provide compelling evidence of a significant association between Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) and an increased risk of Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) in offspring. These findings have important practical implications for clinicians and policymakers. Clinicians should be aware of the potential risks associated with ART and provide appropriate counseling to prospective parents regarding developmental outcomes in children conceived through these methods. Policymakers may need to consider these findings when developing guidelines and support systems for families undergoing ART.

Although this systematic analysis indicates that ART is a risk factor for ASD, the inconsistent findings of a few of the studies imply that more large-scale, prospective, and high-quality research is still required. Such research should aim to elucidate the underlying mechanisms linking ART to ASD and assess the long-term developmental outcomes of children conceived through ART. In conclusion, while current evidence highlights the need for continued monitoring and research, ART seems to remain a vital and generally safe option for individuals experiencing infertility. Clinicians and policymakers should interpret these findings within the broader context of reproductive, developmental, and mental health, with the goal of maintaining a balanced approach that addresses patients’ needs and maintains their safety.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/psychiatryint6040156/s1, PRISMA 2020 completed checklist of the systematic review steps that took place during the synthesis of the systematic review and meta-analysis [23]. Table S1: PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.S., R.A.A. and M.B.A.Z.; methodology, M.A.S., O.A.S., R.A.A. and M.B.A.Z.; formal analysis, M.A.S., T.M., R.A.A. and M.B.A.Z.; investigation, M.A.S., O.A.S. and R.A.A.; data curation, M.A.S., O.A.S., R.A.A. and M.B.A.Z.; writing and original draft preparation, M.A.S., R.A.A. and M.B.A.Z.; writing, review and editing, F.D.A., A.M.A.-O. and T.M.; supervision, F.D.A. and A.M.A.-O.; project administration, M.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The extracted data that was used in this study, in addition to the analysis files are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ledowsky, C.J.; Schloss, J.; Steel, A. Variations in Folate Prescriptions for Patients with the MTHFR Genetic Polymorphisms: A Case Series Study. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2023, 10, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorlandino, C.; Margiotti, K.; Fabiani, M.; Mesoraca, A. Folinic Acid Supplementation during Pregnancy in Two Women with Folate Receptor Alpha Autoantibodies: Potential Prevention of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Offspring. Clin. Transl. Neurosci. 2025, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.J.; Chang, J.; Chawarska, K. Early Generalized Overgrowth in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Prevalence Rates, Gender Effects, and Clinical Outcomes. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 53, 1063–1073.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassimos, D.C.; Syriopoulou-Delli, C.K.; Tripsianis, G.I.; Tsikoulas, I. Perinatal and Parental Risk Factors in an Epidemiological Study of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 62, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croen, L.A.; Najjar, D.V.; Fireman, B.; Grether, J.K. Maternal and Paternal Age Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, C.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K. Preterm or Early Term Birth and Risk of Autism. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2020032300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gialloreti, L.E.; Benvenuto, A.; Benassi, F.; Curatolo, P. Are Caesarean Sections, Induced Labor and Oxytocin Regulation Linked to Autism Spectrum Disorders? Med. Hypotheses 2014, 82, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leavey, A.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Heavner, K.; Burstyn, I. Gestational Age at Birth and Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Alberta, Canada. J. Pediatr. 2013, 162, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, J.; Su, Y.; Lu, H.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Shang, S.; Yue, W. Association of Birth Weight with Risk of Autism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2022, 92, 101934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yu, P.; Wang, Y.; Pei, Y.; Dai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y. The Association between Assisted Reproductive Technologies and Neurodevelopmental Disorders in Offspring: An Overview of Current Evidence. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2024, 23, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvidtjørn, D.; Schieve, L.; Schendel, D.; Jacobsson, B.; Svaerke, C.; Thorsen, P. Cerebral Palsy, Autism Spectrum Disorders, and Developmental Delay in Children Born after Assisted Conception: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2009, 163, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakarneh, M.A.; Sabayleh, O.A.; Alramamneh, A.L.K. The Sensory Characteristics of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Teachers’ Observation. Int. J. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2019, 11, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Gao, J.; He, X.; Cai, Y.; Wang, L.; Fan, X. Association between Assisted Reproductive Technology and the Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorders in the Offspring: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountain, C.; Zhang, Y.; Kissin, D.M.; Schieve, L.A.; Jamieson, D.J.; Rice, C.; Bearman, P. Association between Assisted Reproductive Technology Conception and Autism in California, 1997–2007. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyall, K.; Pauls, D.L.; Spiegelman, D.; Santangelo, S.L.; Ascherio, A. Fertility Therapies, Infertility and Autism Spectrum Disorders in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2012, 26, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushnir, V.A.; Smith, G.D.; Adashi, E.Y. The Future of IVF: The New Normal in Human Reproduction. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 29, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cedars, M.I. In Vitro Fertilization and Risk of Autistic Disorder and Mental Retardation. JAMA 2013, 310, 42–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, E.; Mazzotti, S.; Calderoni, S.; Saviozzi, I.; Guzzetta, A. Are Children Born after Assisted Reproductive Technology at Increased Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorders? A Systematic Review. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 3316–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreadou, M.T.; Katsaras, G.N.; Talimtzi, P.; Doxani, C.; Zintzaras, E.; Stefanidis, I. Association of Assisted Reproductive Technology with Autism Spectrum Disorder in the Offspring: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2021, 180, 2741–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenabi, E.; Bashirian, S.; Khazaei, S.; Farhadi Nasab, A.; Maleki, A. The Association between Assisted Reproductive Technology and the Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorders among Offspring: A Meta-Analysis. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2022, 19, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamowski-Shakibai, M.T.; Magaldi, N.; Kollia, B. Parent-Reported Use of Assisted Reproduction Technology, Infertility, and Incidence of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2015, 9, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, P. Assisted Reproductive Technology and Its Association with Autism in Children. Fertil. Sci. Res. 2021, 8, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velez, M.P.; Dayan, N.; Shellenberger, J.; Pudwell, J.; Kapoor, D.; Vigod, S.N.; Ray, J.G. Infertility and Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Children. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2343954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdalena, H.; Beata, K.; Paprocka, J.; Agnieszka, K.G.; Szczepara-Fabian, M.; Buczek, A.; Ewa, E.W. Preconception Risk Factors for Autism Spectrum Disorder—A Pilot Study. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenabi, E.; Seyedi, M.; Hamzehei, R.; Bashirian, S.; Rezaei, M.; Razjouyan, K.; Khazaei, S. Association between Assisted Reproductive Technology and Autism Spectrum Disorders in Iran: A Case-Control Study. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2020, 63, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diop, H.; Cabral, H.; Gopal, D.; Cui, X.; Stern, J.E.; Kotelchuck, M. Early Autism Spectrum Disorders in Children Born to Fertile, Subfertile, and ART-Treated Women. Matern. Child Health J. 2019, 23, 1489–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lung, F.W.; Chiang, T.L.; Lin, S.J.; Lee, M.C.; Shu, B.C. Assisted Reproductive Technology Has No Association with Autism Spectrum Disorders: The Taiwan Birth Cohort Study. Autism 2018, 22, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotelchuck, M.; Gopal, D.; Kernan, G.; Diop, H. Autism Spectrum Disorders and Assisted Reproductive Technology: Massachusetts 2004–2010 Population-Based Results from Data Linkage Efforts. Int. J. Popul. Data Sci. 2017, 1, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svahn, M.F.; Hargreave, M.; Nielsen, T.S.; Plessen, K.J.; Jensen, S.M.; Kjaer, S.K.; Jensen, A. Mental Disorders in Childhood and Young Adulthood among Children Born to Women with Fertility Problems. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 2129–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kissin, D.M.; Zhang, Y.; Boulet, S.L.; Fountain, C.; Bearman, P.; Schieve, L.; Yeargin-Allsopp, M.; Jamieson, D.J. Association of Assisted Reproductive Technology Treatment and Parental Infertility Diagnosis with Autism in ART-Conceived Children. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehti, V.; Brown, A.S.; Gissler, M.; Rihko, M.; Suominen, A.; Sourander, A. Autism Spectrum Disorders in IVF Children: A National Case-Control Study in Finland. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özbaran, B.; Köse, S.; Ardıç, Ü.A.; Erermiş, S.; Ergin, H.K.; Bildik, T.; Yüncü, Z.; Ercan, E.S.; Aydın, C. Psychiatric Evaluation of Children Born with Assisted Reproductive Technologies and Their Mothers: A Clinical Study. Nöropsikiyatr. Arş. 2013, 50, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grether, J.K.; Qian, Y.; Croughan, M.S.; Wu, Y.W.; Schembri, M.; Camarano, L.; Croen, L.A. Is Infertility Associated with Childhood Autism? J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandin, S.; Nygren, K.G.; Iliadou, A.; Hultman, C.M.; Reichenberg, A. Autism and Mental Retardation among Offspring Born after In Vitro Fertilization. JAMA 2013, 310, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, T.; Kitamoto, A.; Todokoro, A.; Ishii-Takahashi, A.; Kuwabara, H.; Kim, S.-Y.; Watanabe, K.-I.; Minowa, I.; Someya, T.; Ohtsu, H.; et al. Parental Age and Assisted Reproductive Technology in Autism Spectrum Disorders, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, and Tourette Syndrome in a Japanese Population. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2012, 6, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachor, D.A.; Ben Itzchak, E. Assisted Reproductive Technology and Risk for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 32, 2950–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvidtjørn, D.; Grove, J.; Schendel, D.; Schieve, L.A.; Sværke, C.; Ernst, E.; Thorsen, P. Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Children Born after Assisted Conception: A Population-Based Follow-Up Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2011, 65, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimburg, R.D.; Vaeth, M. Do Children Born after Assisted Conception Have Less Risk of Developing Infantile Autism? Hum. Reprod. 2007, 22, 1841–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, D.; Weizman, A.; Ring, A.; Barak, Y. Obstetric Complications in Individuals Diagnosed with Autism and in Healthy Controls. Compr. Psychiatry 2006, 47, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.-F.; Yu, T.; Chen, X.-L.; Luo, R.; Mu, D.-Z. Cerebral palsy in children born after assisted reproductive technology: A meta-analysis. World J. Pediatr. 2021, 17, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnyk, S.; Fuchs, G.J.; Schulz, E.; Lopez, M.; Kahler, S.G.; Fussell, J.J.; Bellando, J.; Pavliv, O.; Rose, S.; Seidel, L.; et al. Metabolic Imbalance Associated with Methylation Dysregulation and Oxidative Damage in Children with Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Källén, B. The risk of neurodisability and other long-term outcomes for infants born following ART. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014, 19, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieve, L.A.; Drews-Botsch, C.; Harris, S.; Newschaffer, C.; Daniels, J.; DiGuiseppi, C.; Croen, L.A.; Windham, G.C. Maternal and Paternal Infertility Disorders and Treatments and Autism Spectrum Disorder: Findings from the Study to Explore Early Development. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 3994–4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidovitch, M.; Chodick, G.; Shalev, V.; Eisenberg, V.H.; Dan, U.; Reichenberg, A.; Sandin, S.; Levine, S.Z. Infertility Treatments during Pregnancy and the Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorder in the Offspring. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 86, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, K.; Carballo, A.; Vega, K.; Talyn, B. A Scoping Review: Risk of Autism in Children Born from Assisted Reproductive Technology. Reprod. Med. 2024, 5, 204–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Geng, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, G. Prenatal, Perinatal, and Postnatal Factors Associated with Autism: A Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2017, 96, e6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).