Abstract

Child sexual abuse (CSA) has consequences beyond the direct victim, affecting non-offending mothers, who may experience psychological, physical, and social symptoms after disclosure. This systematic review examined the impact of CSA on these mothers and the variables that influence coping and recovery. Searches were run in EBSCOhost (MEDLINE, PsycInfo, CINAHL) following PRISMA 2020 and a PEO framework. Three reviewers screened 128 records in Rayyan (Cohen’s κ = 0.73), and 17 empirical studies met the inclusion criteria. Risk of bias was appraised with ROBINS-E. Distress, anxiety, depression, and secondary traumatic stress were the most frequently reported symptoms. These consequences were associated with factors such as maternal history of abuse, perceived social support, coping style, and cultural or religious beliefs, highlighting potentially modifiable cognitive and contextual targets for support. A key contribution of this review is the identification of modifiable cognitive variables that are clinically relevant. Methodological limitations of the evidence base warrant cautious interpretation–comprising seven qualitative, nine quantitative cross-sectional, and one mixed-methods study, with heterogeneity that precluded meta-analysis and limited causal inference. Overall, the findings highlight the need for comprehensive, trauma-informed interventions that address not only the child’s recovery but also the well-being and resilience of their mothers.

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), one in five women and one in seven men report having experienced sexual abuse during childhood. This is therefore a highly prevalent issue affecting children and adolescents worldwide. The WHO also warns that children who have experienced sexual abuse may be at increased risk of perpetrating abuse upon reaching adulthood [1].

There is a persistent discrepancy between the legal and clinical definitions of child sexual abuse (CSA). These differences concern factors such as the age of the perpetrator and the victim, the behaviours considered abusive, and the strategies of coercion [2]. According to Article 181 of the Spanish Penal Code, CSA refers to any person who “engages in sexual acts with a minor under the age of sixteen,” including acts performed by the minor on themselves or on a third party at the instigation of the perpetrator [3].

However, from a healthcare perspective, this legal definition excludes a significant portion of CSA cases, particularly those perpetrated by minors, which account for approximately 20% of all incidents. Health professionals emphasise, instead, the presence of an unequal relationship between the offender and the victim–whether in terms of age, maturity, or power–as well as the use of the minor as a sexual object [2] (p. 33). In this regard, CSA is understood as the involvement of a child or adolescent in any sexual activity they do not understand and for which they lack the developmental capacity to provide valid consent [4].

Moreover, it is difficult to determine the true prevalence of this phenomenon due to several reasons. These include barriers to disclosure of the abuse, the wide range of sexual crimes facilitated by social media, armed conflicts, forced marriages, female genital mutilation, and heterogeneous data collection methods [2,5]. Despite these challenges, some statistical data can offer a clearer picture of CSA in Spain. Some authors estimate that abuse may affect up to 20% of the Spanish population (López, 1994, cited in [2]). A meta-analysis conducted across several countries of America, Asia, Europe, Africa, and Oceania and derived from 100 studies, estimates the prevalence of CSA at 7.4% in boys and 19.2% in girls [6].

From a clinical perspective, there is no diagnostic label or pathology that accounts for CSA or that defines the criminal profile of an abuser. In other words, there is no clear prototype of an offender that can be easily identified, apart from the fact that they tend to present a conventional appearance, average intelligence, and an absence of severe mental disorders.

However, it is also known that men are more frequently responsible for sexually abusing minors than women. According to Echeburúa and Guerricaechevarría, the higher prevalence of male perpetrators may be associated with three main factors. First, a stronger sexual drive influenced by testosterone levels; second, a greater tendency to adopt violent behaviours linked to sexuality; and third, the influence of gender roles and stereotypes that promote high sexual drive, passionate responses, a readiness to engage in sexual activity, and the linking of male status and self-esteem to sexual behaviour [2] (pp. 161–163). In Spain, according to the National Institute of Statistics (INE) in 2023, a total of 314 cases of sexual abuse and assault against minors under the age of 16 involved male offenders, compared to only four committed by women [7].

CSA can be classified according to the type of act or the characteristics of the offender. Classification by action ranges from behaviours involving physical contact, such as fondling, masturbation, or penetration, to non-contact behaviours, including explicit verbal communication, exhibitionism, forced exposure to pornography, and online grooming, among others. The widespread accessibility of the internet has contributed to the emergence of new forms of abuse that fall under the category of non-contact sexual abuse [8]. Additionally, depending on the relationship between the offender and the victim, abuse may be intrafamilial, extrafamilial, or stranger-perpetrated. Research shows that incestuous abuse or abuse by a close acquaintance is more common in children under the age of 13, whereas adolescents are more commonly targeted by strangers [2].

In addition, there are certain risk factors shared by children and teenagers who are victims of CSA, such as coming from environments with low parental supervision, reduced contact with the mother, dysfunctional family dynamics, and a lack of meaningful family support. According to specific studies, particular attention has been drawn to the role of some mothers who, due to a primary identification with their marital role, may exhibit patterns of submission, guilt, and powerlessness, and in some cases minimisation of the abuse–especially if they themselves have previously experienced gender-based violence [9,10].

Beyond the family unit, sociocultural normalisation of CSA represents an additional risk factor. Elements such as market-driven economies–where even people may be treated as commodities–child sex tourism, and persistent CSA-related myths contribute to the societal minimisation of abuse and complicate its disclosure [11]. The endurance of these cultural narratives not only affects the children involved but also directly impacts their mothers, who are often blamed for not having recognized signs of abuse in time. This belief induces feelings of self-blame in mothers, based on the assumption that, within the family setting, the mother is expected to be the “closest” figure to the child and, therefore, should have noticed any signs of abuse prior to its disclosure. In this sense, the mother becomes a secondary victim of the child’s sexual victimisation [12]. This issue requires deeper attention, as the mother’s mental and physical health can be a determining factor in the child’s recovery process.

Recent literature indicates that secondary traumatic stress affects not only professionals but also family caregivers of children who have experienced CSA. In this context, non-offending caregivers, particularly mothers, are included in disclosure-related assessments and in treatment trials, with interventions delivered to the child, the parent, or both [13].

Within trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy (TF-CBT), caregiver participation is essential: the manualised PRACTICE protocol includes work on the trauma narrative and both parallel and conjoint parent–child sessions [14]. At the same time, European national clinical practice guidelines frequently lack key content on interacting with caregivers and on psychological or mental health interventions, underscoring variability and gaps in caregiver-related guidance [15].

Given this reality, it is important to systematise the available evidence to better understand the consequences faced by non-offending mothers as primary caregivers. This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the psychological, physical, social, and economic consequences experienced by mothers of children who have suffered CSA.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Protocol

This systematic review was conducted following the standards of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, to ensure transparency and comprehensive content that allows for replication of the review (see Material S1 in the Supplementary Materials section) [16]. This review was retrospectively registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) to enhance transparency. Details of the time-stamped protocol are provided in the Data Availability Statement.

The research question was as follows: What are the physical, mental, and emotional health repercussions for mothers whose children have been victims of child sexual abuse? To formulate this question, we applied the PICO/PECO guidelines, as explained in the following table.

2.2. Search Strategy

As a first step, we conducted a preliminary exploratory search in scientific databases with the aim of understanding the current state of research on the health impact experienced by mothers whose children have been victims of sexual abuse. Based on this inquiry, we formulated the research question and established the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the systematic review.

We used the EBSCOhost platform to access the following databases: MEDLINE, APA PsycInfo, and CINAHL, selected for their relevance in the fields of medicine, nursing and psychology. A publication date filter was applied, restricting results to those published from the year 2000 onwards. The “proximity” search mode was used, which allows for searching two or more words that appear near each other in the text without requiring an exact phrase match. No additional manual search was conducted.

Subsequently, we conducted the search during February, March, and April 2025. The final search was completed on 2 April via EBSCOhost, accessing the three databases simultaneously, and the results were exported to Rayyan software [17]. The search strategies combined key terms using Boolean operators AND and OR: “(mothers of sexually abused children) AND (child sexual abuse) AND (consequences)”.

The key concepts included: “mothers of sexually abused children”, “maternal distress”, “non-offending mothers”, “child sexual abuse”, and “health impact” or “consequences”. The MeSH thesaurus in Medline was used to identify synonyms for the core concepts. Details of the search equation are available in Table A1.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

The studies were selected based on the following eligibility criteria:

Inclusion criteria:

- Studies that met the PEO guidelines (Table 1);

Table 1. PICO/PECO Model.

Table 1. PICO/PECO Model. - Empirical research, including qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies;

- Publications from the year 2000 onwards;

- Studies published in Spanish or English.

Exclusion criteria:

- Theoretical articles, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses;

- Research focused on other forms of violence without specifically addressing the impact of CSA on mothers;

- Studies analysing only the perspective of healthcare professionals, police officers, lawyers, or other members of the judicial system, without including testimonies or direct data from mothers of children who have been victims of sexual abuse.

While undergraduate or master’s theses were not considered, doctoral dissertations published in recognised academic databases were included, provided they met the established inclusion criteria. This decision was based on the greater methodological rigour, depth of analysis, and peer validation processes typically required for doctoral-level research. These works were assessed based on their empirical nature, originality, and methodological rigour.

2.4. Screening Process and Assessment of Bias

To manage and select the studies, we used the Rayyan software, a tool designed for systematic reviews that facilitates efficient screening of articles. The studies were imported, duplicates were automatically identified and removed, and the predefined eligibility criteria were systematically applied.

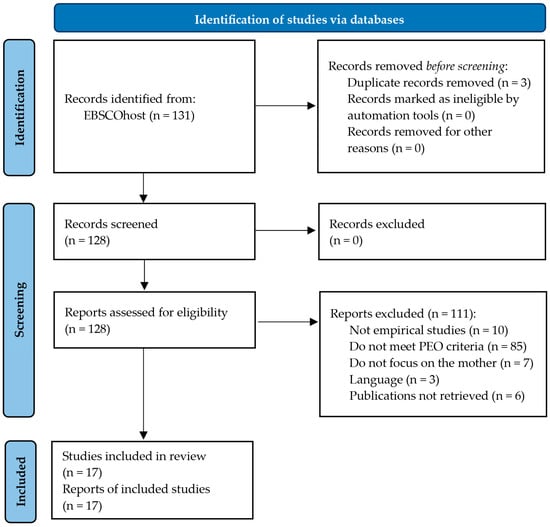

Additionally, a blinded and independent screening was conducted by three reviewers: two carried out the full screening process, while discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer. Inter-rater reliability, assessed through simple percent agreement, was 80.15% across all screening decisions. Cohen’s κ was 0.73, indicating substantial agreement. The adapted PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (Figure 1) documents the process of identification, screening, and selection of the articles.

Figure 1.

Adapted PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram [16].

All screened records (n = 128) were considered to determine their eligibility. Of these, six publications could not be retrieved in full text and were therefore categorised as “not retrieved” in the PRISMA flow diagram. However, these publications were still counted among the assessed records to ensure transparency in the selection process.

To obtain them, we attempted to locate the DOIs of the corresponding journals and, upon finding the articles behind a paywall, we requested them twice through ResearchGate. Unfortunately, these efforts were unsuccessful. Nonetheless, other full texts were successfully retrieved using the same methods. In addition, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and studies that were not empirical were excluded, as well as articles not meeting the PEO criteria, focusing on subjects other than mothers, or written in a language other than English or Spanish.

Finally, we assessed the risk of bias using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomised Studies of Exposures (ROBINS-E) tool [18], which allows for the assessment of bias risk in non-randomised cohort studies. Each study was evaluated across the seven ROBINS-E domains, and the risk of bias was classified as low, moderate, or high. The assessment was included in the results section, and a structured narrative of the judgments for each study is provided in the Supplementary Materials section (see Material S2). Below, we explain what was assessed in each of the seven domains:

- 1

- Confounding factors. We assessed whether the study considered potential confounders that could bias the observed association, including criteria such as: did the authors adequately identify potential confounders; were these measured appropriately and/or controlled for; and did the study collect information indicating the influence of any variables that had not been controlled previously?

- 2

- Measurement of the exposure. We reviewed the quality of the instruments used to measure exposure, outcomes, and other variables, including criteria such as: did the instruments show good validity (measuring what they claim to measure) and reliability (consistency and reproducibility); and were there systematic differences in measurement across groups?

- 3

- Participants in the study. We evaluated whether the way participants were selected might have introduced bias and affected sample representativeness, including criteria such as was the sample was random or based on convenience, and were participants excluded for reasons that could bias the results.

- 4

- Post-exposure interventions. We analysed how the exposure was measured and classified in participants, including criteria such as: Were there misclassification errors (individuals incorrectly categorised)? Was it likely that these errors were related to the outcome?

- 5

- Missing data. We examined whether key data were missing (lost or incomplete) and whether this could have introduced bias, including criteria such as: what proportion of data was missing; and was missingness likely related to exposure or outcome?

- 6

- Outcome measurement. We assessed how the process of measuring results was conducted and whether it could have introduced bias, including criteria such as: were outcomes measured validly and objectively; was there a risk of bias due to knowledge of exposure status?

- 7

- Reported results (selectivity in the presentation of results). We evaluated whether there was reporting bias; that is, whether authors selected only certain results to publish. Criteria included: Is there evidence that some results were omitted? Did the study follow a prior protocol or registered analysis?

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Results and Risk of Bias Assessment

A total of 17 research articles were selected. After the evaluation process of the articles, we conducted a detailed reading. The risk of bias was analysed using the ROBINS-E tool [18], which is presented in Table 2. Accordingly, the main methodological characteristics and relevant findings of each study were extracted and summarised in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5, according to the study design (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-method).

Table 2.

Risk of bias analysis of the selected articles.

Table 3.

Summary and findings of the qualitative studies.

Table 4.

Summary and findings of the quantitative studies.

Table 5.

Summary and findings of the mixed-method study.

3.2. Analysis of Results

To frame the analysis, according to Masilo and Davhana-Maselesele [29,30], CSA is defined as any type of forced, unlawful, and deliberate sexual interaction directed at a minor up to 16 years of age. In contrast, rape refers to forced sexual penetration by a person motivated by sexual gratification or by another coercive or punitive reason involving a child aged 16 or younger.

Regarding the maternal figure of the child victim of CSA, it is understood as any non-offending woman, including stepmothers, caregivers, adoptive or foster mothers, grandmothers, or the biological mother who assumes responsibility for the child who experienced sexual abuse. Finally, the post-abuse disclosure stage refers to the period that begins once the incident of CSA is revealed [29,30].

3.2.1. Types of Maternal Responses Following CSA Disclosure

Moving to maternal responses, not all mothers immediately believe their children when they disclose sexual abuse. Some authors have explored the factors that influence this phenomenon. In particular, there are pre-disclosure variables that condition the caregivers’ beliefs. For example, the nature and closeness of the mother’s current relationship with the perpetrator may lead women to be more or less predisposed to believe their children, especially if there were prior suspicions. The closer the bond, the less support the child tends to receive [32].

Another factor related to responses may be the mother’s history of maltreatment: those who experienced psychological or emotional abuse tend to show more ambivalent responses, provide less support to their children, and adopt avoidant coping strategies, either by minimising the sexual abuse or their own past maltreatment. In contrast, mothers who were victims of physical violence displayed a more protective response and less ambivalence when deciding to separate from the child’s sexual abuser [20].

In other words, unresolved childhood trauma in mothers may hinder their risk perception and prolong ambivalence. In this context, ambivalence refers to caregivers who provide emotional support inconsistently. These types of reactions may involve denying the abuse, postponing protective measures, or maintaining contact with the abuser–either voluntarily or due to coercion from him or external influences [32]. Likewise, psychological distress and a history of CSA in the parents may limit their emotional availability to support their children after disclosure, particularly when they exhibit poor emotional regulation [26,35].

The characteristics of the child victim can also influence maternal behaviour. Specifically, children with more difficult temperaments or psychological and behavioural challenges may pose greater difficulties for their mothers’ responses. Additionally, studies indicate that caregivers tend to assign greater credibility to disclosures made by younger children than by adolescents [22].

It is relevant to recognise the type of response displayed by caregivers of children who have experienced abuse, as it plays a key role in modulating the child’s symptoms and trauma management [21]. Different forms of maternal reactions have been identified depending on the type of relationship the mother maintains with the perpetrator. McMillan [32] established a classification of three response types: (1) mothers who maintain an avoidant and involuntary relationship with the perpetrator, usually due to shared children and legal mandates or previous agreements; (2) women who voluntarily maintain a relationship with the accused, although with little emotional involvement; (3) mothers who remain voluntarily and intimately involved with the perpetrator even after the disclosure, some due to emotional or financial dependency. These different types of relational dynamics influence how mothers process the disclosure and the kind of support they provide to their children [32].

In turn, Cyr et al. [22] proposed another typology of non-offending mothers, considering variables such as the presence of post-traumatic stress symptoms, prior experiences of victimisation, personality traits, current stress levels, and the quality of the emotional bond with the child. Based on this, they identified four main profiles: (1) resilient mothers, who exhibit low levels of PTSD, greater parental sensitivity, and consistent supportive behaviours; (2) avoidant-coping mothers, who tend to minimise the situation, show moderate stress levels, and offer more limited support; (3) traumatised caregivers, with a history of childhood maltreatment, high levels of neuroticism and stress, yet attempting to sustain a relatively functional maternal response; (4) anger-oriented mothers, who display intense PTSD symptoms, greater hostility, punitive or inconsistent parenting practices, and ambivalent attitudes toward the child, alternating between protective behaviours and expressions of rejection or anger. This highlights how multiple factors combine to shape mothers’ ability to provide support and emphasises the importance of adjusting interventions according to the different identified profiles [22].

Following disclosure, parents often feel responsible for protecting their child from the effects of trauma and ensuring their recovery as quickly as possible. Based on this, Cummings [21] proposed the theoretical model “Protecting and Healing,” which describes the process of change in parenting practices after a child’s experience of interpersonal trauma. This model consists of three stages:

- Destabilisation: the initial phase in which parental expectations are shattered. Caregivers enter “protective mode,” redirecting all their resources toward the child’s well-being while setting aside their own needs. The primary focus is on restoring a sense of normality, as they face intense emotions such as shock, disbelief, and a loss of trust in their surroundings.

- Recalibration: as the child begins to show signs of improvement, parents start to adjust their parenting approach. They broaden their focus beyond the trauma, integrate new insights, resume self-care, and promote a more balanced family dynamic.

- Re-stabilisation: a new post-traumatic equilibrium is reached, which not only involves a reduction in negative symptoms, but also the emergence of previously absent benefits–such as improved family communication, stronger bonds, and personal growth [21].

However, not all parents successfully transition to this final stage. The model identifies specific “exit points” or blocks that hinder progress, such as the absence of a psychological rupture in parenting expectations, the inability to implement effective strategies for the child’s benefit, or the emergence of additional adverse events. In such cases, caregivers may remain stuck in earlier stages, unable to complete the recovery process or achieve post-traumatic growth [21].

3.2.2. Sociocultural Factors Influencing Maternal Response

At the sociocultural and individual levels, multiple factors influence caregivers’ responses to CSA disclosure. Among them are individual predispositions stemming from early life experiences–particularly in childhood–which may influence certain personality traits and the ability to cope with adversity. Likewise, the availability of psychological resources and the perceived social support play a significant role in managing highly demanding or traumatic situations [22].

Women who adopt avoidant coping strategies tend to show greater vulnerability to developing PTSD symptoms and experiencing emotional distress, for instance, due to minimising the abusive incident. Nevertheless, these strategies are not always entirely negative; in some circumstances, they may help relieve stress and offer a form of protection that prevents them from feeling emotionally overwhelmed or incapacitated [22,25].

Different religions, such as Catholicism, Judaism and Islam, along with specific sociocultural elements, may influence a mother’s decision to either break or maintain the relationship with her child’s abuser. On one hand, religious beliefs focused on forgiveness, sacrifice, and redemption may lead the caregiver to attempt to support both the child and the abusive partner. On the other hand, cultural contexts with rigid patriarchal norms, deeply rooted gender stereotypes, and traditions that prioritise family unity, obedience, loyalty, and the pressure to uphold the honour of the community and family by avoiding public shame; as well as negative views of divorce or separation, may hinder decisions focused on adequately protecting the child, such as cutting off contact with the perpetrator. In these situations, fear of being rejected or excluded by their family or community can generate intense anxiety [19,28,29].

In more restrictive religious and sociocultural contexts, such as in the ultra-Orthodox Jewish community, certain precepts may even prevent the possibility of reaching the moment of abuse disclosure. For example, the rule of mesirah forbids reporting another community member to civil authorities, except through a rabbi, in order to avoid being sanctioned under laws external to religious doctrine. This can prevent mothers from seeking help or reporting the abuse, due to fear of social stigma and concerns that outsiders might defame their community.

Moreover, this situation is further exacerbated by the lack of sexual education, which limits the ability to speak openly about the abuse, since they are not allowed to mention genitalia and are aware that participating in a police investigation would require doing so [28]. Nevertheless, for many mothers, faith serves as a coping mechanism (and in some cases as a form of avoidance), acting as a decisive factor in achieving acceptance and reframing the meaning of the experience. Some mothers become involved in community activism as part of their search for meaning [28,29].

3.2.3. Psychological, Physical, and Socioeconomic Consequences for Mothers

Mothers of children who have experienced sexual abuse are considered victims of secondary trauma in most studies; however, Plummer [33] notes that they may undergo dual traumatisation–both primary and secondary. It is therefore important to describe the psychological, behavioural, and emotional consequences they may experience.

Caregivers report, among other symptoms, anger towards themselves, towards men as abusers or potential aggressors, and towards the criminal justice system; emotional distress, discomfort, confusion and helplessness. Other reactions included revenge ideation, heightened sexual disgust sensitivity, violent impulses, pain, fear, and anguish. Other difficulties were the perceived lack of support, diminished understanding and trust in current or future relationships, interpersonal sensitivity, hostility, paranoia, and recurrent episodes of crying [24,29,35].

Regarding mental health, several authors identified high levels of depression, distress, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms characterised by an inability to cope with the situation, hyperarousal, avoidant behaviours, and intrusive thoughts. Furthermore, reduced attachment behaviours have been observed, and these symptoms may persist up to four years after the disclosure [25,27,30,35].

Moreover, some mothers have reported experiencing psychosomatic symptoms, guilt, deep emotional suffering, social isolation, decreased self-esteem and self-perception, significant depressive episodes, suicidal ideation, and a deterioration of their maternal self-concept. Trauma-related memory disturbances may also occur, such as fragmented narratives, memory lapses, loss of details, or sudden distractions. The constant presence of the memory of the abuse can severely affect their well-being, daily functioning, and relationship with their children, in addition to making it extremely difficult to process the trauma [27,28,29].

A particularly relevant cognitive pattern in these mothers is rumination, understood as a maladaptive cognitive process involving repetitive and passive focus on distress-related content without progression toward resolution (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991, cited in Plummer, 2006 [33]). In their attempt to make sense of what happened, many mothers tend to fixate on the reasons why the abuse occurred–an approach that can resemble denial–which may influence the severity and duration of their distress, hindering conflict resolution. This cognitive pattern blocks the use of effective coping strategies and intensifies negative emotions such as guilt or hopelessness, thereby impairing both the mother’s recovery process and her ability to protect the child [33].

Along these lines, McGillivray et al. [31] emphasised the importance of certain protective factors that influence the emotional outcomes of non-offending mothers. In their study, those with higher resilience levels experienced significantly lower distress, which was attributed to traits such as self-compassion, perceived social support, and positive reappraisal. The first two factors were associated with reduced distress and increased resilience, whereas positive reappraisal was linked to higher distress–contrary to expectations–perhaps because this adaptive strategy was being used as a form of emotional avoidance when dealing with trauma, preventing its proper processing and perpetuating the suffering [31].

Within the context of cognitive processes, it is important to consider cognitive distortions and attributional style. Accordingly, Runyon et al. [34] found that, in order to reduce maternal distress and increase support for the child, it is necessary to implement treatments focused on abuse-specific cognitions. Individuals with a pessimistic worldview tend to attribute negative events to themselves, believing these situations to be stable and global; that is, that they will remain unchanged and apply to multiple areas of life. For mothers, this translates into beliefs such as the idea that CSA will permanently ruin their child’s life, that the child’s future is destroyed, or that they are at high risk of being revictimised. These cognitive distortions are associated with depressive symptoms, while a more generalised negative attributional style is linked to the development of PTSD in mothers [34].

Although a maternal history of abuse appears as a variable in several studies, no significant differences have been found in levels of depression and anxiety between caregivers with a history of CSA and those who had not been abused [27,30]. However, Dubé et al. [23] reported a greater impact on PTSD symptoms following CSA disclosure in mothers with a personal history of abuse or prior experiences of interpersonal violence, whether in childhood or within intimate partner relationships.

On the other hand, Edwards [24] identified physical health repercussions in women whose children were victims of CSA, including gastrointestinal disturbances, headaches, weakened immune function, dermatological problems, and the worsening of pre-existing illnesses. Furthermore, changes in health-related behaviours were observed, ranging from sleep pattern disruptions to eating-related issues (such as weight loss or gain) and fluctuations in energy levels [24].

Regarding socioeconomic barriers, some studies have found a higher incidence of CSA cases in single-parent households, particularly those led by mothers with low educational attainment and limited economic resources. However, no definitive correlation can be established between CSA and educational or economic level due to the lack of conclusive evidence, as these variables were not controlled for in the studies but rather collected as descriptive information [26,27]. Masilo and Davhana-Maselesele [29] noted that some mothers faced financial difficulties due to unemployment and social isolation, having been excluded from their family, friendship, or community networks out of fear of being blamed or stigmatised for their child’s experience of sexual abuse.

3.2.4. Psychological Intervention Proposals

Currently, there is a significant gap in the literature concerning PTSD symptoms in individuals who have been secondarily exposed to traumatic events, as is the case for many of these mothers. It is relevant to address the secondary traumatic stress they experience, since parental trauma has been shown to be a significant predictor of long-term PTSD symptoms in children, thereby hindering the recovery process for both of them [35].

For this reason, the clinical relevance of targeting parental distress is also emphasised, in order to foster emotional resilience in children following abuse [26]. Among the resources that may serve as protective factors, empowerment stands out, understood as the perception of control over the child’s care and a sense of self-efficacy, which can contribute to more effective management of the child’s response and a reduction in psychological distress among mothers [25].

It is also necessary to consider specific psychological variables that influence maternal response following disclosure, such as disgust, as these help to better understand the challenges faced by caregivers [35]. Additionally, strengthening the attachment bond has been suggested as a therapeutic focus in interventions aimed at mothers of abused children, since greater sensitivity to the disclosure may help facilitate the child’s ability to communicate what happened [27].

Furthermore, the need to explore the history of violence or previous traumatic experiences in mothers has been emphasised, along with the importance of addressing their emotional regulation and coping strategies. Doing so would allow for the design of tailored therapeutic approaches that provide greater control and autonomy in the face of their experiences [20,23,25].

Moreover, it is important to provide comprehensive care for the physical and mental health effects experienced by these women as secondary trauma victims [24]. Finally, it is substantial to consider the different maternal response profiles to adapt interventions to their specific characteristics. This includes adopting a culturally sensitive approach that takes into account the sociocultural factors influencing maternal decision-making, while also promoting a stronger therapeutic alliance and clearer communication [19,22].

In line with this, Plummer [33] identified rumination as a modifiable variable capable of producing high levels of distress and externalised anger. Unlike other uncontrollable factors–such as the abuse experience itself, the mother’s history of CSA, or life stressors–rumination can be assessed and addressed within the framework of psychological treatment. For this reason, she proposed targeting and reducing rumination in mothers of abused children as a therapeutic goal in intervention design [33].

Along these lines, Runyon et al. [34] recommended the use of TF-CBT. The latter aims to restructure abuse-related cognitive distortions, reducing distress, improving maternal coping with CSA, strengthening maternal support, and enhancing positive outcomes in the children [34].

In line with this perspective, McGillivray et al. [31] highlighted the relevance of fostering resilience as a modifiable trait that can be enhanced through clinical interventions. It was therefore suggested that future interventions include components focused on developing self-compassion, social support, and positive reappraisal, with the aim of enhancing resilience and reducing distress in non-offending mothers [31].

It is important to intervene with this group not only for their own emotional well-being, but also because numerous studies have shown that many of these women actively seek help and professional therapy after the disclosure of abuse. For this reason, some authors have proposed the need to establish individual, group, and family therapy that addresses not only secondary traumatisation, but also the associated family dysfunction. These therapeutic dynamics could facilitate identification with other mothers in similar situations, as well as increase the perception of self-efficacy and the sense of parental empowerment. In short, it has been proposed to provide support that addresses emotional, psychological, spiritual, economic, and physical health dimensions [25,29].

In this integrative approach, Masilo and Davhana-Maselesele [30] developed an intervention guide based on the ecological model of the impact of CSA on maternal health. This model considers multiple interrelated levels that may positively or negatively influence the maternal recovery process. These levels include the individual dimension, the assault itself and its consequences, and the micro-, meso-, macro-, and chrono- systems–all of which may contribute to feelings of self-blame and, in turn, increase vulnerability to developing mental illnesses [30].

The guide proposes a comprehensive intervention, coordinated across various social and clinical actors, including psychological treatment, spiritual support, legal guidance, crisis intervention, the formation of support groups, professional training, and community awareness campaigns. The urgency of creating safe and supportive spaces is also emphasised–spaces where mothers can process trauma through coping strategies, reduce stigma, and strengthen their personal and social support networks [30].

4. Discussion

4.1. General Interpretation of Findings

This systematic review rigorously followed PRISMA methodology [16], applying the PEO model to define eligibility criteria, conduct systematic screening, extract methodological characteristics, and analyse the findings for each study. We analysed a total of 17 empirical articles. These studies provide evidence of the psychological, physical, and social consequences for mothers whose children were victims of CSA, as well as the factors that influence maternal responses to disclosure and potential therapeutic interventions. The results indicate that these women experience a complex emotional process, which includes feelings of guilt, self-blame, anger, hopelessness, anxiety, distress, and, in some cases, disorders such as PTSD or depression [22,25,30,33,34,35].

In addition, physical symptoms were identified in some moderate risk of bias studies, although these were less frequently and less thoroughly described in the reviewed articles. Consequently, this scarcity suggests an under-representation of somatic consequences in the current scientific literature. Moreover, Masilo and Davhana-Maselesele suggest non-offending mothers should be provided with psychological, physical and social support [30].

4.2. Modulating Factors and Social Context

We identified different maternal response styles following CSA disclosure, including patterns of protection, as well as validation or disbelief regarding the child’s testimony. These reactions were mediated by variables such as coping style (e.g., the decision to separate from the abuser or not), perceived social support, individual predispositions, personal trauma history, and cultural or religious factors. In this regard, studies from different countries highlighted that mothers reported low levels of perceived social support–not only from family or community networks, but also from the judicial system, medical professionals, and law enforcement agencies [22,25,30,33,35].

Moreover, the analysis of cognitive variables, such as self-efficacy, rumination and negative attributional style, was a key contribution of this review, as it identified potentially modifiable clinical targets with direct therapeutic implications. Likewise, resilience, self-compassion, and social support emerged as key protective factors that can guide future interventions focused on promoting maternal well-being [22,25,30,33,34].

4.3. Methodological Limitations of the Present Review

After applying the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria and conducting the screening process using the Rayyan platform, we selected a total of 17 empirical articles from an initial pool of 128 records. Most of the selected studies showed a moderate risk of bias, according to the assessment conducted with the ROBINS-E tool. While this does not invalidate their findings, it does suggest that the results should be interpreted with caution. For this reason, a conservative approach was adopted to account for the heterogeneous nature of the evidence, and only the symptoms and consequences described in the six studies with low risk of bias are presented in detail in this section.

One of the main limitations observed in the reviewed studies was the lack of methodological homogeneity, which made it difficult to perform more rigorous systematic comparisons. Additionally, there was a notable absence of longitudinal research and clinical trials capable of evaluating the effectiveness of interventions specifically designed for this group. Most of the studies were cross-sectional and descriptive, which limits the scope of the conclusions that can be drawn.

On the other hand, although some studies addressed caregivers more generally, the samples were predominantly composed of mothers. This over-representation may be due to the search equation prioritising terms specifically related to mothers, or to a greater willingness among mothers to participate. Future studies should aim to explore the experiences of other non-offending caregivers in order to broaden the understanding of the phenomenon.

Limitations of this review should also be noted. The search was restricted to MEDLINE, APA PsycInfo, and CINAHL and to publications in English or Spanish, and six full texts could not be obtained despite attempts to locate journal DOIs and to contact corresponding authors via ResearchGate. These factors may have introduced language, database, or retrieval bias.

Furthermore, we recognise the heterogeneity within the PEO framework (Population, Exposure, Outcome). This heterogeneity was addressed through qualitative synthesis and thematic categorisation of the findings, as suggested by PRISMA and JBI guidelines for integrative or non-meta-analytic systematic reviews. Its impact on the interpretation of the findings is also acknowledged as a limitation of this review.

Study designs were heterogeneous and predominantly non-longitudinal, seven qualitative, nine quantitative cross-sectional, and one mixed-methods, which precluded meta-analysis and limited inference to associations rather than causation. In this context, interpretations and implications are presented cautiously and aligned with the strength, design, and consistency of the available studies, since cross-sectional and qualitative designs do not establish temporal precedence and therefore cannot determine whether mothers’ symptomatology follows the child’s experience or predates it.

A narrative synthesis was adopted, without formal sensitivity analyses. This decision was driven by the complex nature of the outcomes and the substantial heterogeneity observed in populations, instruments, and effect metrics, which made a meta-analysis not feasible.

4.4. Intervention Proposals and Future Directions

Although multiple studies have shown that mothers of children who have experienced sexual abuse develop significant losses and trauma [22,25,30,33,34,35], there is a general lack of interventions specifically adjusted to their needs and personal characteristics, which represents a key area of opportunity for clinical research.

We recommend developing clinical programmes focused on strengthening their emotional competencies, including TF-CBT, emotional regulation techniques, and the reinforcement of support networks [25,30,33,34]. In addition, it would be relevant to investigate how maternal mental health influences the child’s recovery process, promoting integrated mother–child therapeutic models.

5. Conclusions

This review synthesises empirical evidence on an understudied population: mothers of children who have experienced CSA. It underscores the need to address maternal emotional health, not only for their individual well-being, but also for its potential impact on the child’s recovery [34], given the complex psychological, physical, and social consequences observed.

Taken together, three domains warrant equal consideration: maternal symptomatology; contextual and social–cognitive factors shaping responses; and gaps in tailored therapeutic provision. Across the included studies, reporting was most consistent for symptomatology and contextual factors, whereas proposed clinical models appeared in fewer studies and are therefore presented as directions for practice rather than established standards.

Specific clinical models and targets supported within this review include:

- TF-CBT, which has been suggested to help restructure abuse-specific cognitions, reduce maternal distress, and improve maternal coping with CSA;

- Rumination-focused interventions, recommended as a modifiable driver of symptoms;

- Resilience-oriented components;

- Empowerment and reinforcement of support networks;

- Culturally sensitive approaches; and

- An ecological, multi-level intervention guide coordinating psychological treatment with spiritual, legal, crisis, group, and community resources.

Future research should prioritise longitudinal studies and intervention trials that test these approaches with mothers, addressing the methodological gaps identified. We suggest clinical practice should, in turn, establish caregiver-focused pathways that integrate TF-CBT-informed, resilience-building and network-strengthening components within context-sensitive care. This dual agenda is aligned with the proposals and findings synthesised in this review and aims to improve maternal well-being and support child recovery.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/psychiatryint6040158/s1; Material S1: The PRISMA Checklist; Material S2: ROBINS-E Structured Narrative Judgements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.V. and I.I.M.; methodology, S.A.V. and I.I.M.; validation, S.A.V., I.I.M. and J.J.M.A.; formal analysis, S.A.V.; investigation, S.A.V., J.J.M.A. and I.I.M.; resources, I.I.M.; data curation, S.A.V., I.I.M. and J.J.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.V.; writing—review and editing, S.A.V. and I.I.M.; visualisation, S.A.V.; supervision, I.I.M.; project administration, I.I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This systematic review used already published data. The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The protocol of this review was retrospectively registered in the OSF and is openly available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/VWCZH.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| CSA | Child sexual abuse |

| INE | National Institute of Statistics |

| TF-CBT | Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy |

| OSF | Open Science Framework |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PEO | Population, exposure, outcome |

| ROBINS-E | Risk of Bias in Non-randomisedrandomized Studies of Exposures |

| IPV | Intimate partner violence |

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Search equation.

Table A1.

Search equation.

| Equation | Justification |

|---|---|

| ((“mothers of sexually abused children” OR “mothers of child sexual abuse survivors” OR “maternal experience” OR “maternal response” OR “parental response” OR “maternal adjustment” OR “maternal distress” OR “non-offending mothers” OR “maternal trauma” OR “maternal reaction” OR “maternal experience”) | Corresponds to the P (Population) component of the PEO model. It is also linked to the third exclusion criterion, as it focuses on studies specifically addressing mothers, not other actors. |

| AND (“child sexual abuse” OR “sexual abuse survivors” OR “childhood sexual trauma” OR “CSA” OR “child abuse” OR “child molestation” OR “sexual abuse of child” OR “sexual child molestation” OR “sexually abused children” OR “children exposed to sexual violence” OR “sexual victimisation of children”) | Corresponds to the E (Exposure) component of the PEO model. It connects with the second exclusion criterion, which targets studies specifically related to CSA. |

| AND (“impact” OR “consequences” OR “effects” OR “coping” OR “stress” OR “trauma” OR “psychological impact” OR “mental health” OR “social impact” OR “family dynamics” OR “economic impact” OR “health impact”)) | Related to the O (Outcome) component of the PEO model: effects on physical, mental, emotional, or social health. This supports the inclusion of studies that specifically address the repercussions of CSA on mothers. |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Child Maltreatment 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/child-maltreatment (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Echeburúa, E.; Guerricaechevarría, C. Abuso Sexual en la Infancia: Nuevas Perspectivas Clínicas y Forenses, 2nd ed.; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 2021; pp. 23–163. [Google Scholar]

- Jefatura del Estado. Ley Orgánica 10/1995, de 23 de Noviembre, Del Código Penal; Jefatura del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 1995; Volume BOE-A-1995-25444, pp. 33987–34058. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/1995/11/23/10/con (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Durán Sáez, M.P. El Abuso Sexual Infantil: Reflexiones Críticas Sobre Textos Publicados Entre 2015–2020. Una Revisión. Revista Inclusiones: Revista de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales 2024, 11, 192–225. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=9637421 (accessed on 25 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Pueyo, A.; Nguyen-Vo, T.; Rayò-Bauzà, A.; Redondo-Illescas, S. Análisis Empírico Integrado y Estimación Cuantitativa de los Comportamientos Sexuales Violentos (No Consentidos) en España. Violencia Sexual en España: Una Síntesis Estimativa; Grupo de Estudios Avanzados en Violencia (GEAV), Universidad de Barcelona, Ministerio del Interior: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pereda, N.; Guilera, G.; Forns, M.; Gómez-Benito, J. The Prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: A meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Delitos Sexuales Según Sexo. 2024. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=28750 (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Pereda, N. El espectro del abuso sexual en la infancia: Definición y tipología. Revista de Psicopatología y Salud Mental del Niño y del Adolescente 2010, 16, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Apraez-Villamarin, G.E. Factores de riesgo de abuso sexual infantil. Antistio Rev. Cient. INMLCF Colomb. 2015, 2, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, L.F.C.; Conceição, O.C.; Machado, S. Childhood and adolescent sexual abuse, victim profile and its impacts on mental health. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2017, 22, 2919–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Manuel Vicente, C. Detectando el abuso sexual infantil. Pediatría Atención Primaria 2017, 19, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, Q.C.M.; Galvão, M.T.G.; Cardoso, M.V.L.M.L. Child sexual abuse: The perception of mothers concerning their daughters’ sexual abuse. Rev. Latino-Am. Enferm. 2009, 17, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, P.; Turner, W.; Caldwell, D.M.; Macdonald, G. Comparative effectiveness of psychological interventions for treating the psychological consequences of sexual abuse in children and adolescents: A network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 2023, CD013361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielemann, J.F.B.; Kasparik, B.; König, J.; Unterhitzenberger, J.; Rosner, R. Stability of treatment effects and caregiver-reported outcomes: A meta-analysis of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for children and adolescents. Child Maltreatment 2024, 29, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterman, G.; Nurmatov, U.B.; Akhlaq, A.; Korhonen, L.; Kemp, A.M.; Naughton, A.; Chalumeau, M.; Jud, A.; Vollmer-Sandholm, M.J.; Mora-Theuer, E.; et al. Clinical care of childhood sexual abuse: A systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines from European countries. Lancet Reg. Health–Eur. 2024, 39, 100868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 Explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Morgan, R.L.; Rooney, A.A.; Taylor, K.W.; Thayer, K.A.; Silva, R.A.; Lemeris, C.; Akl, E.A.; Bateson, T.F.; Berkman, N.D.; et al. A tool to assess risk of bias in non-randomized follow-up studies of exposure effects (ROBINS-E). Environ. Int. 2024, 186, 108602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaggia, R. Cultural and religious influences in maternal response to intrafamilial child sexual abuse: Charting new territory for research and treatment. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2001, 10, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaggia, R.; Turton, J.V. Against the odds: The impact of woman abuse on maternal response to disclosure of child sexual abuse. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2005, 14, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.A. Transformational Change in Parenting Practices after Child Interpersonal Trauma: A Grounded Theory Examination of Parental Response. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 76, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, M.; McDuff, P.; Hébert, M. Support and profiles of nonoffending mothers of sexually abused children. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2013, 22, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, V.; Tremblay-Perreault, A.; Allard-Cobetto, P.; Hébert, M. Alexithymia as a mediator between Intimate Partner Violence and Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in mothers of children disclosing sexual abuse. J. Fam. Violence 2024, 39, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.N. Feelings and Health Effects Experienced by Non-Offending Mothers Whose Prepubescent Daughters Disclosed Sexual Abuse by a Known Perpetrator. Doctoral Dissertation, Texas Woman’s University, USA, Denton, TX, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hébert, M.; Daigneault, I.; Collin-Vézina, D.; Cyr, M. Factors linked to distress in mothers of children disclosing sexual abuse. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2007, 195, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langevin, R.; Hébert, M.; Allard-Dansereau, C.; Bernard-Bonnin, A.-C. Emotion regulation in sexually abused preschoolers: The contribution of parental factors. J. Trauma. Stress 2016, 29, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, L.; Bergin, C. Attachment Behaviors, depression, and anxiety in nonoffending mothers of child sexual abuse victims. Child Maltreat 2001, 6, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinsky, A.S.; Goldner, L. “God, why?”: The experience of mothers from the Israeli ultra-orthodox sector after their child’s disclosure of sexual abuse. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP16799–NP16828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masilo, G.M.; Davhana-Maselesele, M. Experiences of mothers of sexually abused children in North-West province, post disclosure. Curationis 2016, 39, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masilo, G.M.; Davhana-Maselesele, M. Guidelines for support to mothers of sexually abused children in North-West province. Curationis 2017, 40, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGillivray, C.J.; Pidgeon, A.M.; Ronken, C.; Credland-Ballantyne, C.A. Resilience in non-offending mothers of children who have reported experiencing sexual abuse. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2018, 27, 793–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, L. Non-Offending Mothers of Sexually Abused Children: How They Decide Whom to Believe. Doctoral Dissertation, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Plummer, C.A. Non-Abusive Mothers of Sexually Abused Children: The Role of Rumination in Maternal Outcomes. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2006, 15, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runyon, M.K.; Spandorfer, E.D.; Schroeder, C.M. Cognitions and distress in caregivers after their child’s sexual abuse disclosure. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2014, 23, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Delft, I.; Finkenauer, C.; Tybur, J.M.; Lamers-Winkelman, F. Disgusted by sexual abuse: Exploring the association between disgust sensitivity and posttraumatic stress symptoms among mothers of sexually abused children. J. Trauma. Stress 2016, 29, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).