Abstract

Traumatic experiences are among the strongest predictors of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, but the mechanisms that account for this association are still debated. Sleep disturbances, particularly insomnia, nightmares, and fragmented sleep, are highly prevalent after trauma and have been shown to predict suicidality independently of depression and other psychiatric comorbidities. This narrative mini-review synthesizes evidence from epidemiological, clinical, and experimental studies to examine whether sleep may represent a pathway linking trauma and suicidality. Among the proposed mechanisms, alterations in REM sleep regulation, dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, and impaired prefrontal control of emotional reactivity have received empirical support, although findings remain inconsistent across populations. Importantly, trauma-related nightmares and persistent insomnia appear to be especially strong markers of elevated suicide risk. Clinically, these observations suggest that routine sleep assessment could add value to suicide risk evaluation in trauma-exposed individuals. Interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, imagery rehearsal therapy, and REM-modulating pharmacological treatments have shown promise, but their specific impact on suicidality requires further testing in controlled trials. Future research should prioritize longitudinal designs, incorporate both subjective and objective sleep measures, and include culturally diverse samples to clarify causal mechanisms and refine prevention strategies.

1. Introduction

Traumatic experiences—ranging from early-life challenges like childhood abuse and neglect to adult encounters such as interpersonal violence, accidents, and combat—are some of the most powerful and consistent risk factors for suicidal thoughts, suicide attempts, and suicide deaths throughout life [1,2]. These events can trigger a complex web of interconnected neurobiological and psychosocial processes, including persistent activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, dysregulation of autonomic arousal systems, structural and functional changes in the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex, as well as long-lasting shifts in emotion regulation and cognitive control [3,4,5]. These alterations contribute to a heightened state of physiological and psychological vulnerability that can persist for years or even decades after the initial trauma.

Sleep disturbances are among the most common and distressing effects of trauma exposure. Insomnia, recurring nightmares, fragmented sleep, changes in slow-wave sleep, and issues with REM sleep are very common in trauma-exposed groups, especially among those with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [6]. Importantly, these sleep problems are not just secondary symptoms of psychiatric issues; growing evidence suggests that they may be key mechanisms linking trauma to various negative mental health outcomes, including suicidality [7,8].

Over the past two decades, converging epidemiological and clinical research has shown that sleep disturbances—particularly insomnia and trauma-related nightmares—are independent predictors of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide deaths, even after adjusting for depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, and other known risk factors [9,10]. Prospective studies have also demonstrated that changes in sleep patterns, especially worsening insomnia or increasing nightmare frequency, often occur before the onset or escalation of suicidal thoughts and behaviors [11,12,13]. This temporal sequence supports the idea that disturbed sleep may serve as a mediating pathway through which the lasting effects of trauma contribute to suicidal risk.

From a mechanistic standpoint, trauma-related sleep disturbances may exacerbate suicide risk via several interrelated processes. Neurobiological alterations—such as increased noradrenergic tone, reduced GABAergic inhibition, and impaired synaptic plasticity in circuits regulating emotional reactivity—can disrupt the normal restorative and memory-consolidating functions of sleep [14,15]. This, in turn, may impair the overnight downscaling of negative emotional salience, perpetuate intrusive memories, and limit the extinction of fear responses. Psychologically, inadequate or dysregulated sleep compromises emotion regulation, increases hopelessness, impairs problem-solving abilities, and heightens impulsivity—all well-established proximal risk factors for suicide [16].

Importantly, sleep represents a modifiable risk factor within the trauma–suicidality pathway. Several intervention modalities have demonstrated promise in targeting sleep to reduce suicide risk: cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), imagery rehearsal therapy for recurrent nightmares, pharmacotherapies that stabilize REM sleep architecture, and integrated treatments combining sleep interventions with trauma-focused psychotherapy [17]. These approaches have shown beneficial effects not only on sleep quality but also on reductions in suicidal ideation, suggesting that improving sleep may yield downstream benefits on suicide risk.

Despite increasing awareness of sleep’s role in trauma-related suicidality, few studies have specifically examined sleep disturbances as mediators between trauma exposure and suicidal behaviors. Most research has focused on simple associations, leaving a gap in comprehensive models that include biological, psychological, and social risk factors. Addressing this gap has important implications for clinical screening, risk assessment, and developing multi-layered prevention strategies.

This mini-review aims to synthesize current evidence on the mediating role of sleep disturbances in the relationship between trauma and suicidality. Specifically, we (i) summarize the literature linking trauma exposure to sleep disturbances, (ii) review evidence connecting sleep disturbances to suicidal ideation and behavior, (iii) explore theoretical and empirical models positioning sleep disturbances as mediators in the trauma–suicidality pathway, and (iv) discuss the clinical and public health implications of these findings. By integrating evidence from diverse populations and methodological approaches, this review seeks to highlight the crucial importance of sleep-focused interventions in reducing suicide risk among trauma-exposed individuals.

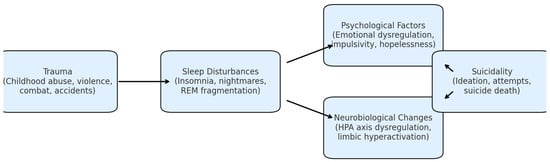

Figure 1 presents the proposed conceptual model outlining the mediating role of sleep disturbances in the trauma–suicidality pathway.

Figure 1.

Proposed conceptual model of sleep disturbances mediating the trauma–suicidality pathway.

2. Methods

This paper takes the form of a narrative mini-review rather than a systematic or scoping review. I chose this approach to provide a concise and conceptually driven summary of the most relevant evidence on the trauma–sleep–suicidality pathway, rather than a comprehensive review of all available studies. Narrative mini-reviews are well-suited when the literature is diverse in design and outcomes, and when the goal is to highlight connections between mechanisms and clinical implications across various fields [18,19]. This approach enabled me to bring together epidemiological, clinical, and experimental findings within a unified framework, while keeping the scope and focus manageable.

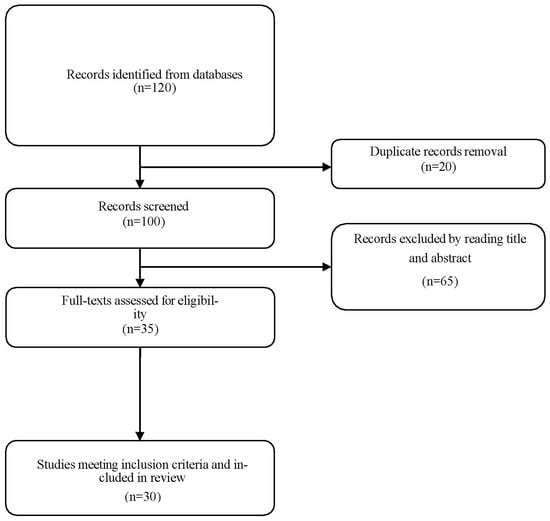

Accordingly, this narrative mini-review is based on a targeted literature search conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science up to July 2025. Search terms combined trauma-related keywords (“trauma”, “post-traumatic stress disorder”, “childhood maltreatment”), suicidality (“suicide”, “suicidal ideation”, “suicide attempt”), and sleep disturbances (“insomnia”, “nightmares”, “sleep fragmentation”). Priority was given to peer-reviewed studies in English, without publication year restrictions, including epidemiological, clinical, and experimental research. Reference lists of relevant articles and recent systematic reviews were also screened. Inclusion criteria were: (i) peer-reviewed articles in English; (ii) human participants with documented trauma exposure reporting sleep disturbances and suicidality; (iii) epidemiological, clinical, or experimental designs; and (iv) original data or theoretical models addressing at least one link in the trauma–sleep–suicidality pathway. Exclusion criteria were: (i) case reports or qualitative studies without quantitative sleep/suicide data; (ii) conference abstracts without full text; and (iii) animal studies. A flow chart of the study selection process is presented in Figure 2, showing the identification of records, exclusion after title/abstract screening, and the number of full-text articles included in the narrative synthesis. Although a PRISMA-style flow diagram is provided to increase transparency of the search and screening process, this review should not be interpreted as a systematic review. The synthesis presented here is narrative in nature and was not conducted with the methodological rigor or comprehensive scope required for systematic or scoping reviews.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of study identification, screening, and inclusion for the narrative mini-review.

3. Trauma and Suicidality

Traumatic experiences are consistently recognized as major risk factors for suicidal thoughts, suicide attempts, and suicide deaths throughout the lifespan [20]. Childhood maltreatment—including physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, as well as neglect—has been linked to a two- to five-fold increased risk of later suicidality, with stronger effects observed for repeated or chronic exposure [21]. Adult-onset traumas, such as intimate partner violence, sexual assault, and combat exposure, also significantly raise the risk of suicidal behaviors, especially when combined with pre-existing psychiatric vulnerabilities [22,23].

The relationship between trauma and suicidality is complex. At the neurobiological level, trauma exposure can cause lasting changes in stress-response systems, including increased activity of the HPA axis, dysregulation of the noradrenergic system, and structural and functional alterations in the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex [4,24]. These changes hinder the ability to regulate negative emotions, manage stress responses, and prevent maladaptive behaviors—all essential for reducing suicide risk.

From a psychological perspective, trauma can lead to persistent cognitive distortions such as negative self-assessment, hopelessness, and feelings of entrapment, which are immediate risk factors for suicidal thoughts [25,26,27]. Additionally, post-traumatic emotional dysregulation—characterized by increased reactivity to negative stimuli, difficulty managing anger, and reduced tolerance for distress—can increase the risk of impulsive suicidal behaviors [28]. The presence of comorbid psychiatric disorders, especially major depressive disorder, PTSD, and borderline personality disorder, further amplifies the impact of trauma on suicide risk [29].

The temporal relationship between trauma exposure and suicidality is complex. Some individuals exhibit acute suicidal crises shortly after trauma, while others develop chronic vulnerability, with elevated risk persisting years after the event [30,31]. This persistence may reflect the interaction between enduring neurobiological alterations and reinforcing psychosocial factors such as social isolation, stigma, and lack of access to appropriate mental health care [32].

Given the strong and consistent link between trauma and suicidality, international guidelines for suicide prevention recommend systematic screening for trauma history in both psychiatric and general medical settings [33]. However, despite widespread awareness of this connection, relatively few studies have examined intermediate mechanisms—such as sleep disturbances—that may explain how trauma increases the risk of suicidal behaviors. Understanding these pathways is essential for identifying modifiable targets for intervention and for developing comprehensive prevention strategies.

4. Trauma and Sleep Disturbances

Sleep disturbances are among the most common and persistent effects of traumatic experiences, occurring both immediately after the event and as long-term symptoms [32]. In populations with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), prevalence is particularly high: epidemiological studies indicate that up to 90% of individuals with PTSD suffer from insomnia, recurring nightmares, or both [33]. Importantly, however, even trauma-exposed individuals who do not meet full PTSD criteria often report clinically significant sleep problems—such as difficulty falling asleep, frequent nighttime awakenings, and non-restorative sleep [34].

The relationship between trauma and sleep is bidirectional: trauma exposure disrupts sleep continuity and architecture, while poor sleep quality may worsen post-traumatic symptoms, creating a self-perpetuating cycle [34]. For example, insomnia during the early post-trauma phase has been shown to predict the later development of PTSD, regardless of initial symptom severity [34]. Nightmares, especially those involving re-experiencing the traumatic event, are hallmark features of PTSD and are strongly linked to greater illness severity, emotional dysregulation, and decreased quality of life [35].

From a neurobiological perspective, trauma-related sleep disturbances are associated with dysregulation of the HPA axis, increased nocturnal sympathetic activity, and changes in neurotransmitter systems, including elevated noradrenergic tone and decreased GABAergic inhibition [36]. Functional neuroimaging studies have shown abnormal activation of the amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus during both wakefulness and REM sleep in individuals exposed to trauma, suggesting that sleep disruption may hinder the processing and integration of emotional memories [37].

Polysomnographic investigations in PTSD have reported shortened REM latency, increased REM density, and heightened REM fragmentation [38]. These alterations may reflect a failure of REM sleep to perform its adaptive role in emotional memory extinction, thereby contributing to the persistence of intrusive memories and hyperarousal. Non-REM (NREM) sleep has also been implicated, with studies showing reduced slow-wave sleep (SWS) in trauma-exposed individuals—including but not limited to those with PTSD—potentially impairing restorative functions and increasing vulnerability to stress [39].

Clinically, sleep disturbances in both trauma survivors with PTSD and those without a full PTSD diagnosis are associated with greater psychiatric comorbidity, impaired psychosocial functioning, and increased healthcare utilization [39]. Interventions targeting trauma-related sleep problems—such as CBT-I, imagery rehearsal therapy for nightmares, and pharmacological agents modulating REM sleep—have demonstrated improvements not only in sleep parameters but also in core PTSD symptoms [38].

Despite this strong evidence, the role of sleep disturbances as a mechanistic link between trauma and later psychiatric outcomes, including suicidality, remains underexplored. This gap highlights the need for integrated research to examine how trauma-related sleep changes contribute to the development and persistence of suicidal risk—a focus that will be explored in the upcoming sections of this review.

5. Sleep Disturbances and Suicidality

A growing body of evidence indicates that sleep disturbances are not merely correlates of psychiatric disorders but represent independent risk factors for suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide deaths [40]. Meta-analyses have consistently shown that insomnia, hypersomnia, and recurrent nightmares are associated with a two- to three-fold increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, even after adjusting for depressive symptoms and other psychiatric comorbidities [41]. Importantly, this association has been documented across diverse populations, including adolescents, military personnel, psychiatric inpatients, and individuals with chronic medical conditions [42,43,44]. These associations are supported by consistent evidence from meta-analyses and longitudinal studies and can therefore be regarded as well-established findings.

Insomnia—particularly difficulties in sleep initiation and maintenance—has emerged as one of the most robust sleep-related predictors of suicidality [40]. Longitudinal studies indicate that persistent insomnia increases the risk of suicide attempts over follow-up periods ranging from months to years, independent of baseline depression severity [45,46]. Experimental research suggests that insomnia may contribute to suicide risk by impairing cognitive control, amplifying negative affect, and heightening impulsive responding to emotional stimuli [47].

Nightmares, especially those with recurrent or trauma-related content, are also strongly linked to suicidality. Their frequency and distress are associated with increased hopelessness, perceived burdensomeness, and thwarted belongingness—core constructs of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide [4]. Intervention studies have demonstrated that reducing nightmare frequency through imagery rehearsal therapy or pharmacological treatments (e.g., prazosin) is associated with decreases in suicidal ideation [48].

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the sleep–suicide connection. Neurobiologically, sleep deprivation and fragmentation can cause hyperactivation of limbic areas (such as the amygdala) and decreased prefrontal regulatory control, leading to increased emotional reactivity and impulsivity [15]. Psychologically, poor sleep quality hampers problem-solving skills, reduces resilience to stress, and heightens feelings of entrapment and hopelessness [15]. Importantly, these mechanisms may function independently of psychiatric diagnoses, indicating that sleep disturbances should be viewed as a separate factor in suicide risk assessment. Since they are modifiable, sleep disturbances are critical targets for suicide prevention efforts. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that CBT-I, even in brief or online formats, can reduce suicidal thoughts in both clinical and non-clinical populations [14]. Likewise, targeted treatment for nightmares has been linked to improved sleep quality and decreased self-harm behaviors [20].

Recognizing sleep disturbances as modifiable, immediate risk factors highlights the importance of regular sleep assessments for individuals at higher risk of suicide. However, the extent to which sleep disturbances serve as mediators between upstream risk factors—like trauma—and suicidal outcomes remains inadequately researched. This gap in knowledge will be addressed in the next section, which focuses on the mediating role of sleep disturbances in the trauma–suicidality pathway.

6. Sleep as a Mediator Between Trauma and Suicidality

While the associations between trauma and suicidality, and between sleep disturbances and suicidality, are well documented, the hypothesis that sleep disturbances mediate the trauma–suicidality relationship has received comparatively less empirical attention. Mediation implies that trauma leads to sleep disruption, which in turn contributes to the onset or escalation of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. This conceptualization is consistent with stress–diathesis models of suicide, where sleep disturbances represent a modifiable intermediate phenotype linking distal risk factors to proximal suicidal crises [41].

Several studies have provided indirect support for the mediating role of sleep disturbances. In trauma-exposed military personnel, insomnia severity has been shown to account for a significant proportion of the variance in suicidal ideation, independent of depression and PTSD severity [41]. In adolescents with a history of childhood maltreatment, poor sleep quality partially mediated the relationship between trauma exposure and current suicidal thoughts [11]. Similarly, in survivors of interpersonal violence, nightmare frequency mediated the link between post-traumatic stress symptoms and suicide risk [32]. These findings suggest that both quantitative (sleep duration, sleep efficiency) and qualitative (sleep continuity, nightmare distress) aspects of sleep may function as critical pathways from trauma to suicidality.

It should be noted, however, that most available studies are cross-sectional and often involve relatively small samples, which limits their ability to determine temporal order and causality. Therefore, the mediating role of sleep disturbances in the trauma–suicidality pathway should be considered preliminary, needing confirmation from larger longitudinal and experimental studies.

From a neurobiological perspective, trauma-induced sleep disturbances may impair the processing of emotional memories, reduce prefrontal inhibitory control over limbic activation, and exacerbate dysregulation of the HPA axis [7,8,9]. REM sleep fragmentation may interfere with the extinction of fear memories, perpetuating hyperarousal and intrusive recollections [10]. Alterations in slow-wave sleep may impair overnight emotion regulation and recovery from stress, further increasing vulnerability to suicidal crises [11].

While these proposed mechanisms are theoretically coherent and supported by preliminary studies, they remain hypotheses that require further empirical confirmation through longitudinal and experimental designs.

These mechanisms provide a coherent framework for understanding how trauma-related sleep disturbances could serve as proximal drivers of suicidal behavior.

Psychologically, disturbed sleep following trauma can amplify negative affects, hopelessness, and feelings of entrapment [12,13]. Chronic insomnia is associated with attentional bias toward threat, impaired problem-solving ability, and reduced cognitive flexibility—factors that have been directly linked to suicidal behavior [14,15]. Moreover, nightmares may act as nocturnal re-experiencing episodes, reinforcing maladaptive cognitions about the self and the world, and perpetuating emotional distress [16].

If sleep disturbances indeed mediate the trauma–suicidality link, then interventions targeting sleep could have downstream effects on suicide risk. CBT-I and imagery rehearsal therapy for nightmares have demonstrated efficacy in improving sleep and reducing suicidal ideation in trauma-exposed populations [17,18,19]. Pharmacological agents that stabilize REM sleep architecture, such as prazosin, may further reduce both nightmares and suicidal thoughts in PTSD [20]. Importantly, such interventions may be beneficial even when implemented outside the context of formal trauma-focused psychotherapy, highlighting the value of sleep-focused prevention strategies in diverse clinical settings.

Despite promising preliminary evidence, most studies examining the mediation hypothesis are cross-sectional, limiting causal inference. There is a need for longitudinal research employing rigorous mediation analyses, with repeated assessments of trauma exposure, sleep parameters, and suicidal outcomes over time. Such studies should integrate both subjective and objective sleep measures (e.g., polysomnography, actigraphy) to clarify the temporal dynamics and mechanistic specificity of sleep’s mediating role. The studies included in this review come from a wide range of countries and populations, including adolescents, adults, veterans, and trauma survivors, and they employ both epidemiological and clinical designs. Measures vary from self-reported sleep quality and suicidal ideation to objective actigraphy and randomized controlled trials. To provide an overview of these contributions, Table 1 summarizes representative studies examining the trauma–sleep–suicidality pathway, highlighting different populations, study designs, and key findings that complement the conceptual model discussed in the text.

Table 1.

Summary of key studies examining the trauma–sleep–suicidality pathway.

7. Clinical and Public Health Implications

The evidence supporting a mediating role of sleep disturbances in the trauma–suicidality pathway has important implications for clinical practice and public health policy. First, it underscores the necessity of routine sleep assessment in individuals with a history of trauma, regardless of whether they meet criteria for PTSD or other psychiatric diagnoses [1,2]. Simple, validated instruments such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) or the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) can be easily integrated into clinical intake procedures in psychiatric, primary care, and community health settings [3,4].

Second, the mediation model suggests that sleep-focused interventions may serve a dual function—ameliorating sleep disturbances while simultaneously reducing suicide risk. CBT-I and imagery rehearsal therapy for nightmares have demonstrated efficacy across trauma-exposed populations, including veterans, survivors of interpersonal violence, and individuals with childhood maltreatment histories [5,6,7]. Importantly, these interventions can be delivered through various modalities, including group formats, telehealth, and brief primary care-based protocols, enhancing their scalability [8,9].

Digital CBT-I programs, for example, have shown significant improvements in sleep and psychological well-being in large randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses [49,56], underscoring their potential for broad dissemination.

Third, recognizing sleep as a modifiable suicide risk factor opens new avenues for integrated care. Embedding sleep interventions within trauma-focused psychotherapies (e.g., prolonged exposure, cognitive processing therapy) could enhance overall treatment outcomes by addressing both core PTSD symptoms and downstream suicide risk [10,11]. In high-risk populations—such as adolescents in foster care, victims of domestic violence, and recently discharged psychiatric inpatients—early intervention on sleep problems may serve as a preventative measure against future suicidal crises [12,13,14].

From a public health perspective, integrating sleep health into suicide prevention efforts, training mental health professionals in evidence-based sleep interventions, and ensuring access to these treatments through healthcare systems are essential steps to lower suicide rates among trauma-exposed populations [15,16]. From a health economics perspective, short and scalable interventions—such as digital CBT-I or group-based imagery rehearsal therapy—can offer significant clinical benefits with minimal resource use, making them especially suitable for low- and middle-income countries or underfunded health services. These methods require fewer specialized resources and can be integrated into primary care or community mental health settings. In resource-limited contexts, adding sleep modules to existing trauma-focused or general mental health programs may enhance outcomes without substantially increasing costs.

Despite their promise, several barriers could hinder the widespread adoption of sleep-focused interventions in suicide prevention. These include the need for proper clinician training in evidence-based sleep therapies, limited awareness among healthcare providers about the link between sleep and suicidality, and challenges with patient adherence—especially for multi-session behavioral treatments. Structural barriers, such as the separation between sleep medicine and mental health services, can also limit coordinated care. Overcoming these obstacles through targeted education, cross-disciplinary collaboration, and simplified intervention formats will be crucial for translating research into routine practice.

8. Conclusions

Traumatic experiences have deep and lasting effects on mental health, significantly raising the risk of suicidal thoughts and actions. Sleep disturbances are among the most common and persistent results of trauma and are now recognized as independent risk factors for suicidality. Current research suggests that sleep issues may act as mediators in the link between trauma and suicidality, through both neurobiological and psychological pathways. However, while this mediating role is promising, available data are still limited and do not allow for firm conclusions about causality.

Recognizing this potential pathway has important clinical implications: it highlights sleep as a modifiable target for intervention and prevention, with the possibility of reducing the progression from trauma exposure to suicidal crisis. By routinely screening for and treating sleep problems in trauma-exposed individuals, clinicians may enhance sleep and overall functioning while potentially lowering suicide risk.

Future studies should address several gaps that remain in the current evidence base, including the following:

- (i)

- Longitudinal designs incorporating repeated measures of trauma exposure, sleep parameters, and suicidal outcomes, ideally with both subjective and objective assessments such as polysomnography and actigraphy.

- (ii)

- Multiple mediation models that integrate biological (e.g., HPA axis function, neuroimaging markers) and psychological (e.g., emotion regulation, hopelessness) variables to capture the complexity of the trauma–sleep–suicidality pathway.

- (iii)

- Intervention studies that directly test whether improving sleep quality leads to measurable reductions in suicidality among trauma-exposed populations, including randomized controlled trials comparing standard care with sleep-focused add-on treatments.

- (iv)

- Exploration of non-Western perspectives on trauma, sleep, and suicidality, as sociocultural contexts can influence both the experience of trauma and how sleep disturbances manifest, potentially affecting pathways to suicidal risk.

Incorporating sleep-centered care into standard trauma and suicide prevention protocols remains a promising, scalable, and evidence-based approach, but further evidence is needed before definitive conclusions can be drawn.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data extracted and analyzed in this review are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Baldini, V.; Gottardi, C.; Di Stefano, R.; Rindi, L.V.; Pazzocco, G.; Varallo, G.; Purgato, M.; De Ronchi, D.; Barbui, C.; Ostuzzi, G. Association between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Suicidal Behavior in Affective Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Psychiatry 2025, 68, e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, I.; Austin, J.L.; Gooding, P. Association of Childhood Maltreatment with Suicide Behaviors among Young People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2012563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, C.; Nemeroff, C.B. The Role of Childhood Trauma in the Neurobiology of Mood and Anxiety Disorders: Preclinical and Clinical Studies. Biol. Psychiatry 2001, 49, 1023–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrory, E.J.; Viding, E. The Theory of Latent Vulnerability: Reconceptualizing the Link between Childhood Maltreatment and Psychiatric Disorder. Dev. Psychopathol. 2015, 27, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, A. Sleep Disturbances as the Hallmark of PTSD: Where Are We Now? Am. J. Psychiatry 2013, 170, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellman, T.A.; Hipolito, M.M.S. Sleep Disturbances in the Aftermath of Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. CNS Spectr. 2006, 11, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldini, V.; Gnazzo, M.; Santangelo, G.; D’Agostino, A.; Varallo, G.; Scorza, M.; Ostuzzi, G.; Galeazzi, G.M.; De Ronchi, D.; Plazzi, G. Are Sleep Disturbances a Risk Factor for Suicidal Behavior in the First Episode of Psychosis? Evidence from a Systematic Review. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2025, 185, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernert, R.A.; Hom, M.A.; Iwata, N.G.; Joiner, T.E. Objectively Assessed Sleep Variability as an Acute Warning Sign of Suicidal Ideation in a Longitudinal Evaluation of Young Adults at High Suicide Risk. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2017, 78, e678–e687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Spreckelsen, P.; Schouten, D.; Waslam, N.G.; Katuin, P.; Heering, H.D.; Planting, C.; Antypa, N.; Kivelä, L.; Lancel, M.; Schweren, L.J.S. The Effect and Safety of Sleep Interventions on Suicidal Thoughts and Behavior—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Sleep Med. X 2025, 10, 100145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.T.; Steele, S.J.; Hamilton, J.L.; Do, Q.B.P.; Furbish, K.; Burke, T.A.; Martinez, A.P.; Gerlus, N. Sleep and Suicide: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 81, 101895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.; Hom, M.A.; Rogers, M.L.; Stanley, I.H.; Ringer-Moberg, F.B.; Podlogar, M.C.; Hirsch, J.K.; Joiner, T.E. Insomnia and Suicide-Related Behaviors: A Multi-Study Investigation of Thwarted Belongingness as a Distinct Explanatory Factor. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 208, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palagini, L.; Baglioni, C.; Ciapparelli, A.; Gemignani, A.; Riemann, D. REM Sleep Dysregulation in Depression: State of the Art. Sleep Med. Rev. 2013, 17, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, W.V.; Benca, R.M.; Rosenquist, P.B.; Youssef, N.A.; McCloud, L.; Newman, J.C.; Case, D.; Rumble, M.E.; Szabo, S.T.; Phillips, M.; et al. Reducing Suicidal Ideation through Insomnia Treatment (REST-IT): A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 2019, 176, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trockel, M.; Manber, R.; Chang, V.; Thurston, A.; Tailor, C.B. An E-Mail Delivered CBT for Sleep-Health Program for College Students: Effects on Sleep Quality and Depression Symptoms. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2011, 7, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, A.N.; Walker, M.P. The Role of Sleep in Emotional Brain Function. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 10, 679–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porras-Segovia, A.; Pérez-Rodríguez, M.M.; López-Esteban, P.; Courtet, P.; Barrigón, M.M.L.; López-Castromán, J.; Cervilla, J.A.; Baca-García, E. Contribution of Sleep Deprivation to Suicidal Behaviour: A Systematic Review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2019, 44, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakazu, V.A.; Assis, M.; Bacelar, A.; Bezerra, A.G.; Ciutti, G.L.R.; Conway, S.G.; Galduróz, J.C.F.; Drager, L.F.; Khoury, M.P.; Leite, I.P.A.; et al. Industry Sponsorship Bias in Randomized Controlled Trials of Digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia: A Meta-Research Study Based on the 2023 Brazilian Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Insomnia in Adults. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1600767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.N.; Johnson, C.D.; Adams, A. Writing Narrative Literature Reviews for Peer-Reviewed Journals: Secrets of the Trade. J. Chiropr. Med. 2006, 5, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, R. Writing Narrative Style Literature Reviews. Med. Writ. 2015, 24, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yegen, R.; Özdemir Bişkin, S. Dating Violence and Childhood Traumatic Experience: The Mediating Role of Rejection Sensitivity, Irrational Beliefs. J. Interpers. Violence 2025, 8862605251357853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.Y.; Park, C.H.K. Interpersonal Constructs in the Mediation of Early Maladaptive Schemas and Suicidal Ideation among Outpatients with Major Depressive Disorder. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2025, 40, e173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Liu, H.; Zhou, X.; Huang, X. Depression and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: The Mediating Roles of Childhood Trauma and Impulsivity. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1580235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, D.J.; Chiu, W.T.; Hwang, I.; Kessler, R.C.; Sampson, N.; Alonso, J.; Borges, G.; Bromet, E.; Bruffaerts, R.; de Girolamo, G.; et al. Cross-National Analysis of the Associations between Traumatic Events and Suicidal Behavior: Findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottley, J.K.; Devries, K.; Edwards, P.; Miguel-Esponda, G.; Roberts, T.; Larrieta, J.; Rathod, S.D. Mediators of the Association between a Parent’s Experience of Trauma and Their Children’s Well-Being: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2025, 15248380251357616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Peng, S.; Liu, Q.; Wang, W.; Lu, C.; Jiang, X.; Guo, L. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adolescent Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: The Role of Social Support in a National Survey on Sexual Orientation and Gender Expression. Child Abus. Negl. 2025, 167, 107576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Keyworth, C.; O’Connor, D.B. Effects of Childhood Trauma on Mental Health Outcomes, Suicide Risk Factors and Stress Appraisals in Adulthood. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, R.C.; Kirtley, O.J. The Integrated Motivational–Volitional Model of Suicidal Behaviour. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 20170268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirci, A.E.; Sar, V.; Cetin, A. Cross-Sectional Analysis of Psychological Mediators between Occupational Trauma and PTSD in Metropolitan Firefighters. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jiang, C.; Wang, X.; Qiu, H.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Q.; Ju, Y. Childhood Maltreatment and Mental Health: Causal Links to Depression, Anxiety, Non-Fatal Self-Harm, Suicide Attempts, and PTSD. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2025, 16, 2480884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannoy, S.; Bountress, K.; Stephenson, M.; Edwards, A.C. The Roles of Adverse Childhood Experiences and Genetic Liability in Risk for Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors: A Factor Analytic Approach. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 383, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Borges, G.; Walters, E.E. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Lifetime Suicide Attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1999, 56, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Munisamy, Y.; Ai, T.; Yoon, S.; Kim, J.; Pon, A. Typologies of Childhood Maltreatment and Associations with Internalizing Symptoms among University Students in Singapore: A Latent Class Analysis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0320851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyoseph, Z.; Levkovich, I.; Rabin, E.; Shemo, G.; Szpiler, T.; Shoval, D.H.; Belz, Y.L. Applying Language Models for Suicide Prevention: Evaluating News Article Adherence to WHO Reporting Guidelines. NPJ Ment. Health Res. 2025, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Xiao, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, R.; Xu, S.; Su, T. The Mediating Role of Sleep in PTSD and Positive/Negative Emotional States during the COVID-19 Resurgence. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpviken, A.N.; Jensen, T.K.; Johnson, S.U.; Ormhaug, S.M.; Birkeland, M.S. Assessing Change and Persistence of Specific Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms among Youth in Trauma Treatment. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2025, 16, 2515683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Held, P.; Boland, A.; Pridgen, S.A.; Smith, D.L. Sleep Disturbances and PTSD: Identifying Baseline Predictors of Insomnia Response in an Intensive Treatment Programme. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2025, 16, 2514885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, J.; Liu, L.; Yu, P.; Ren, Z. Exploring Emotion Regulation in PTSD with Insomnia: A Task-Based fMRI Study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2025, 189, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.-L.; Chan, D.Y.-C.; Chan, D.T.-M.; Cheung, M.-C.; Shum, D.H.-K.; Chan, A.S.-Y. Transcranial Photobiomodulation Improves Cognitive Function, Post-Concussion, and PTSD Symptoms in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2025, 42, 1695–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, A.-F.; Lai-Trzebiatowski, J.; Smith, T.; Calloway, T.; Aden, C.; Jovanovic, T.; Smith, B.; Carrick, K.; Munoz, A.; Jung, M.; et al. Acupuncture for Anxiety, Depression, and Sleep in Veterans with Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teresi, G.I.; Davis, M.; Williamson, A.A.; Young, J.F.; Merranko, J.A.; Goldstein, T.R. Sleep Disturbances Are Associated with Depressive Symptoms and Suicidality among Adolescents in Pediatric Primary Care. JAACAP Open 2024, 3, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, Q. Predictors and Risk Factors for Suicide in Late-Life Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1636838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-J.; Huang, Y.-H.; Cheng, W.-J. Sedative-Hypnotics Are Associated with Additional Risk of Suicide in Older Adults: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. Sleep 2025, zsaf136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, V.; Varallo, G.; Redolfi, S.; Liguori, R.; Plazzi, G. Exploring Sleep Quality, Depressive Symptoms, and Quality of Life in Adults with Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2025, 50, 105317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffa, J.W.; Raines, A.M.; Franklin, C.L.; Beckham, J.C.; Stecker, T. Insomnia, Social Disconnectedness, and Suicidal Ideation Severity in Underserved Veterans. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2025, 49, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Gong, W.; Shang, X.; Ruan, J.; Liang, W.; Lin, Z.; Li, S. Nonrestorative Sleep Is Associated with Self-Injury Behavior and Suicidal Ideation in Chinese Adolescents: A Longitudinal Study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyniak, C.P.; Donohue, M.R.; Tillman, R.; Thompson, R.J.; Going, B.; Barch, D.; Luby, J.L. The Temporal Dynamics of Sleep Disturbances, Depression, and Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors in Preadolescents: A Year-Long Intensive Longitudinal Study. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2025, 53, 1169–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauducco, S.V.; Tilton-Weaver, L.; Gradisar, M.; Hysing, M.; Latina, D. Sleep Trajectories and Frequency of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Adolescents: A Person-Oriented Perspective over Two Years. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krakow, B.; Hollifield, M.; Johnston, L.; Koss, M.; Schrader, R.; Warner, T.D.; Tandberg, D.; Lauriello, J.; McBride, L.; Cutchen, L.; et al. Imagery Rehearsal Therapy for Chronic Nightmares in Sexual Assault Survivors with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2001, 286, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, S.R.; Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Chapman, D.P.; Williamson, D.F.; Giles, W.H. Childhood Abuse, Household Dysfunction, and the Risk of Attempted Suicide Throughout the Life Span: Findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA 2001, 286, 3089–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigeon, W.R.; Britton, P.C.; Ilgen, M.A.; Chapman, B.; Conner, K.R. Sleep Disturbance Preceding Suicide Among Veterans. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102 (Suppl. 1), S93–S97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, A.N.; Walker, M.P. The Neuroscience of Sleep and Emotion. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2014, 28, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskind, M.A.; Peterson, K.; Williams, T.; Hoff, D.J.; Hart, K.; Holmes, H.; Homas, D.; Hill, J.; Daniels, C.; Calohan, J.; et al. A Trial of Prazosin for Combat Trauma PTSD with Nightmares in Active-Duty Soldiers. Am. J. Psychiatry 2013, 170, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espie, C.A.; Emsley, R.; Kyle, S.D.; Gordon, C.; Drake, C.L.; Siriwardena, A.N.; Cape, J.; Ong, J.C.; Sheaves, B.; Foster, R.; et al. Effect of Digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia on Health, Psychological Well-Being, and Sleep-Related Quality of Life: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cen, Y.; He, J.; Zhong, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zeng, J.; Huang, G.; Luo, J. The Mediating Role of Sleep Problems and Depressed Mood Between Psychological Abuse/Neglect and Suicidal Ideation in Adolescents: A Multicentred, Large-Sample Survey in Western China. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littlewood, D.L.; Kyle, S.D.; Pratt, D.; Peters, S.; Gooding, P. Examining the Role of Sleep Problems in the Development of Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviours: A Longitudinal Study in a Clinical Sample of Adults with Major Depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 190, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariae, R.; Lyby, M.S.; Ritterband, L.M.; O’Toole, M.S. Efficacy of Internet-Delivered Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Sleep Med. Rev. 2016, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).