Abstract

Suicide remains one of the leading causes of death worldwide, yet psychiatry continues to assess risk primarily through suicidal ideation. This narrow focus overlooks a critical factor: sleep. A growing body of evidence demonstrates that insomnia, nightmares, and circadian disruption are consistent and potentially modifiable correlates of suicidal behavior across various diagnoses and age groups, supported primarily by longitudinal and prospective studies. Despite this, structured sleep assessment is seldom integrated into routine psychiatric care, predominantly due to cultural inertia and inadequate training. This perspective necessitates a shift: sleep assessment should be regarded alongside mood and cognition in every evaluation of suicide risk. Brief questionnaires and targeted interventions are readily accessible and feasible for implementation, thereby presenting concrete opportunities for prevention. By incorporating sleep evaluation into standard practice and future predictive models, psychiatry can advance toward more precise, actionable, and timely suicide prevention. To continue neglecting sleep is to overlook one of the most accessible and effective means of saving lives.

1. Introduction

Suicide remains a devastating global health issue. According to the World Health Organization, nearly 800,000 people die by suicide each year, which equals one death every 40 s [1]. The causes of suicide are multifactorial, resulting from the complex interaction between biological vulnerabilities and social factors, which together influence individual risk trajectories [2,3].

The consequences extend far beyond the individuals who die, impacting families, friends, and entire communities, leaving grief that lasts across generations. Suicide is also among the leading causes of death among adolescents and young adults, making it not only a medical emergency but also a developmental and societal tragedy [4,5].

Historically, the psychiatric literature has oscillated between biological reductionism and psychosocial explanations of suicide. Early psychoanalytic accounts emphasized unconscious drives, while subsequent decades highlighted serotonergic dysregulation, family history, and heritable risk [6]. More recent approaches have incorporated sociological perspectives, focusing on social cohesion, economic adversity, and cultural norms [7]. While each framework has provided valuable insights, the tendency to privilege mood and cognition has led to a neglect of physiological domains such as sleep, which are no less fundamental to human functioning [8].

Despite decades of research, the ability to predict suicide remains limited. Psychiatric assessments still focus on suicidal ideation, hopelessness, and prior attempts [9]. While these are important, they are not enough. Many people who ultimately die by suicide explicitly deny suicidal thoughts when asked, sometimes in the days or even hours before their death. Others show no overt psychiatric decompensation but remain at elevated risk anyway. This mismatch between assessment and outcome reveals a fundamental weakness in how psychiatry understands risk. It indicates that the field must look beyond ideation and mood to broader, complementary areas of vulnerability.

The field has therefore dedicated considerable effort to refining existing predictors, such as hopelessness, impulsivity, or access to means, yet the accuracy of these factors remains limited.

Sleep is one of the most promising fields. It is universal, measurable, and modifiable, and it is closely linked to mental health. Despite being closely linked to mental health, sleep has often been treated as a secondary concern in psychiatry. Yet, growing evidence indicates that its systematic assessment could strengthen suicide prevention.

In this manuscript, the term sleep disturbance is used to describe symptom-level problems such as insomnia symptoms, nightmares, or circadian misalignment, regardless of formal diagnosis. The term sleep disorder is reserved for conditions meeting established diagnostic criteria (e.g., insomnia disorder, delayed sleep–wake phase disorder).

Suicide risk assessment has historically relied on frameworks that prioritize mood symptoms, hopelessness, and explicit suicidal ideation [10]. The stress–diathesis model of suicide, for instance, underscores the interaction between long-standing vulnerabilities (such as impulsivity, aggression, and biological predispositions) and proximal stressors, but it does not systematically consider sleep. Similarly, interpersonal theories of suicide emphasize thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness as drivers of suicidal desire, yet omit the role of sleep disruption in shaping social withdrawal, affective instability, and cognitive distortions. This historical gap has contributed to a siloed approach where sleep is viewed as secondary rather than integral. Reframing these models to incorporate sleep not only acknowledges its independent predictive power but also situates it within the broader biopsychosocial architecture of suicide. A more comprehensive framework, therefore, requires conceptualizing sleep as a transdiagnostic factor that cuts across diagnoses, cultures, and developmental stages.

2. Evidence Linking Sleep Disturbance and Suicidality

2.1. Insomnia

Most of the evidence linking insomnia to suicidality comes from cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, with a smaller number of prospective cohorts examining the emergence or persistence of suicidal thoughts over time. Although interventional data are still limited, findings consistently show that sleep difficulties precede and accompany elevated suicide risk.

Insomnia is one of the most consistent correlates of suicidal ideation and behavior [11]. A recent meta-analysis reveals that adolescents with persistent difficulties initiating or maintaining sleep are at significantly higher risk of suicidal thoughts compared with those who sleep well [12]. Importantly, this relationship is not simply explained by comorbid depression or anxiety. Several large-scale studies have found that the association between insomnia and suicidality persists after adjusting for mood disorder severity [13,14].

Longitudinal data strengthen the evidence. In prospective cohorts, insomnia has been associated with the emergence of new suicidal ideation and with transitions from ideation to attempts [15,16], although causal direction cannot yet be established [17]. The chronicity of insomnia matters: persistent sleep difficulties are associated with a higher risk than transient or situational problems, suggesting a cumulative effect. One striking finding comes from cohort studies linking chronic insomnia to increased suicide mortality, highlighting its relevance not only for ideation but for lethal outcomes [18,19].

Clinical samples reflect these findings. Among psychiatric inpatients, treatment-resistant insomnia has been linked to more frequent suicidal crises during hospitalization, regardless of diagnosis or medication status [20]. In outpatient groups, residual insomnia after depression appears to be a strong predictor of relapse and suicidal thoughts, emphasizing that sleep issues often indicate incomplete recovery and ongoing vulnerability. These findings indicate that insomnia may serve as an important clinical warning sign for suicide risk, even though its causal role remains to be fully clarified. Beyond psychiatric samples, population-based studies confirm that insomnia exerts effects even in individuals without current mental disorders, suggesting that its influence is not merely epiphenomenal to depression or anxiety [20]. Notably, sex-specific patterns have emerged: women with chronic insomnia often display elevated ideation rates, while men with severe sleep maintenance difficulties may show higher transition to attempts. Cultural factors may also shape this association; in societies with later bedtimes or more permissive attitudes toward sleep variability, insomnia’s impact on suicidality may be mediated by social jet lag rather than absolute duration. These nuances highlight that insomnia is a multifaceted risk marker, requiring careful assessment beyond the presence or absence of sleep complaints.

Mechanistically, insomnia appears to intensify cognitive patterns central to suicidality. Difficulty initiating sleep fosters rumination during nocturnal wakefulness, often focused on negative self-appraisals or perceived burdensomeness. Repeated nights of disrupted sleep create a vicious cycle in which hopeless thoughts become more salient in the absence of restorative rest. Over time, the erosion of problem-solving capacity and the amplification of catastrophic thinking may act as accelerators toward suicidal behavior. These processes are particularly evident in adolescents and young adults, for whom late-night rumination coincides with heightened impulsivity.

The practical implication is clear: insomnia should not be dismissed as a secondary complaint in the hierarchy of psychiatric symptoms. Routine assessment of sleep continuity, duration, and quality can reveal risks that standard mood inventories might overlook. Moreover, given that insomnia is amenable to brief and scalable interventions, including cognitive–behavioral therapy and digital self-help programs, its identification represents not only a diagnostic opportunity but also a modifiable entry point for suicide prevention.

2.2. Nightmares

Evidence regarding nightmares and suicidality is derived primarily from cross-sectional and longitudinal designs, while only a few randomized controlled trials have indirectly examined the effects of nightmare treatment on suicidal ideation. Thus, the relationship should be interpreted as associative, though supported by convergent data across populations.

Nightmares are a robust, independent correlate of suicidal ideation and behavior, supported by longitudinal and registry data [21,22]. Far from being harmless nocturnal experiences, nightmares serve as emotional stressors that reinforce feelings of defeat and helplessness. They are strongly associated with suicidal ideation and attempts in both community and clinical settings [23]. Their predictive value remains, regardless of trauma history, PTSD severity, or depressive symptoms, suggesting that nightmares may play an active role in suicidality, though definitive causal evidence is still limited [24].

Evidence extends beyond trauma-exposed adults. In adolescents, recurrent nightmares predict suicidal ideation and non-suicidal self-injury, even after controlling for depression and family conflict [25]. Among older adults, nightmares often co-occur with neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and REM sleep behavior disorder, and their presence has been associated with heightened rates of both depressive symptoms and suicidal behavior [26]. These findings emphasize that nightmares are a lifespan phenomenon with clinical significance across developmental and medical contexts.

Military veterans exemplify this risk. Nightmares are common in trauma-exposed populations and often persist despite treatment [27]. Veterans experiencing recurrent nightmares face a significantly higher risk of suicide attempts and deaths compared to those without such nightmares, as confirmed by registry analyses in trauma-exposed veterans.

Mechanistically, nightmares may act through several pathways. Recurrent threatening imagery disrupts the restorative function of REM sleep, leading to heightened arousal and impaired emotional regulation during the day. The content of nightmares often includes themes of defeat, humiliation, or death, which can normalize or rehearse suicidal cognitions. The anticipatory anxiety of going to sleep itself can also create a sense of entrapment, reinforcing hopelessness. These processes suggest that nightmares function not only as markers of trauma exposure but as active generators of suicide risk.

Importantly, therapeutic treatments that reduce nightmares, such as imagery rehearsal therapy, have been associated with decreases in suicidal thoughts, though whether this reflects a causal effect remains to be determined [28].

The clinical implications are profound. Nightmares are easily identifiable through brief patient reports, yet they are seldom systematically assessed during psychiatric evaluations. Incorporating standard questions about nightmare frequency and distress could enhance suicide risk detection with minimal burden on clinicians. Furthermore, effective interventions exist—not only imagery rehearsal therapy but also pharmacological options such as prazosin, which has demonstrated benefits in reducing trauma-related nightmares. Broader dissemination of these approaches, supported by clinical guidelines and training programs, could transform nightmares from a neglected symptom into a central target of suicide prevention.

2.3. Circadian Disruption

Research on circadian disruption and suicide is emerging, with most studies being observational. While longitudinal cohorts and shift-work studies indicate temporal associations with suicidal ideation and attempts, causal inference remains preliminary, and interventional evidence is still scarce.

Circadian misalignment constitutes a third pathway. Adolescents diagnosed with delayed sleep phase disorder, who have difficulty initiating sleep until late at night, encounter early school start times that limit sleep duration, resulting in chronic deprivation. This pattern is consistently linked to increased suicidal ideation and self-harm [29]. Among adults, shift workers with irregular schedules demonstrate higher incidences of depression and suicidality compared to day workers, with the risk escalating proportionally to the extent of circadian disruption [30].

Additional high-risk groups include university students, who often have irregular sleep–wake patterns due to balancing academic demands and social jet lag, and medical residents, whose long shifts and overnight duties can impair judgment and increase suicidal thoughts. In older adults, disruption of circadian rhythms is connected not only to depression but also to cognitive decline, which further elevates the risk of suicidal behavior. These findings show that circadian misalignment is not limited to specific disorders but occurs whenever environmental pressures clash with biological timing.

Biological evidence substantiates these associations. Suicidal individuals frequently exhibit irregular melatonin rhythms, diminished cortisol fluctuations, and modified circadian gene expression. These findings imply that circadian misalignment is not merely socially disruptive but also biologically destabilizing, potentially contributing to the risk of suicide. Disruption of circadian rhythms also interferes with neurotransmitter regulation. Misalignment of sleep and wake cycles alters dopaminergic and glutamatergic transmission, impairing reward processing and stress adaptation. At the behavioral level, chronic circadian irregularity reduces consistency in daily routines, weakening protective structures such as regular meals, social contact, and physical activity. The combined effect of biological instability and behavioral disorganization magnifies the risk of suicidal crises, particularly in individuals with pre-existing psychiatric conditions.

Importantly, circadian misalignment does not merely represent a lifestyle inconvenience. Emerging evidence links circadian gene variants, such as CLOCK and PER3 polymorphisms, with both delayed sleep phase and suicidal behaviors. This biological overlap suggests, but does not yet confirm, that disrupted circadian timing may contribute to mood dysregulation and impulsivity, thereby increasing suicide risk.

Such findings underscore the need for psychiatry to view circadian health not as a peripheral lifestyle issue but as a biological substrate of vulnerability.

Clinically, circadian disruption can be identified through simple questions about sleep timing, work schedules, or chronotype preference, yet these factors are seldom explored during standard psychiatric interviews. Interventions such as light therapy, melatonin supplementation, and structured activity scheduling show that circadian health can be improved. On a societal level, delaying school start times and regulating shift schedules for essential workers have been shown to improve sleep duration, mood stability, and daytime functioning. Whether such policies can also reduce suicidal behavior remains to be determined, but their evaluation represents an important public health priority. Recognizing circadian misalignment as both a clinical and societal target could therefore guide future studies toward more comprehensive approaches to suicide prevention.

2.4. Across the Lifespan

The association between sleep disturbance and suicidality extends across the lifespan. In children and adolescents, insufficient sleep duration and irregular sleep patterns serve as predictors for irritability, impulsivity, and self-injurious behavior. Transitional periods, such as puberty and the perinatal phase, deserve special attention. During puberty, shifts in circadian phase preference combined with early school start times create chronic misalignment, which exacerbates impulsivity and mood instability. In the perinatal period, fragmented sleep and insomnia are early markers of postpartum depression, a condition strongly associated with suicidal ideation and, in some cases, maternal mortality. These examples underscore that changes in biological rhythms during sensitive developmental windows can amplify suicide risk.

Among young adults, notably university students, poor sleep quality and reduced sleep duration are consistently associated with suicidal ideation, even when academic stress and mood disorders are accounted for [19].

Gender differences also emerge. Adolescent girls reporting poor sleep are more likely to develop suicidal thoughts, whereas boys often manifest the risk through increased impulsivity and self-harm. In older age, women may report sleep complaints more frequently, but men display higher lethality of suicidal acts, suggesting that underrecognized sleep disturbance in men may translate into more fatal outcomes. Cultural factors further shape these patterns: in collectivist societies, where family support buffers distress, the link between sleep and suicidality may be attenuated, whereas in highly competitive academic or work environments, insufficient sleep appears to exert a stronger effect.

In older adults, sleep fragmentation, early awakenings, and comorbid insomnia heighten susceptibility, especially in the context of medical illnesses and social isolation [20]. This is of particular concern in older men, who exhibit some of the highest rates of suicide globally, for whom sleep disturbance may constitute an underrecognized warning indicator.

From a clinical perspective, tailoring suicide prevention to developmental stage is essential. Pediatricians and school health services can integrate brief sleep assessments into routine visits, while universities might implement sleep education and screening as part of student well-being programs. In geriatric care, early recognition of insomnia and fragmented sleep could serve as accessible markers of vulnerability, prompting timely psychosocial or medical interventions. At the policy level, public health initiatives that promote healthy sleep—through school scheduling, workplace protections, and geriatric outreach—offer scalable strategies to mitigate suicide risk across the lifespan.

2.5. Mechanisms Linking Sleep and Suicide

The strength of the sleep–suicide link is reinforced by plausible psychological and biological mechanisms.

Sleep deprivation impairs emotional regulation. Neuroimaging research indicates that sleep deprivation heightens amygdala reactivity to negative stimuli while decreasing the functional connectivity between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex [21]. This imbalance results in a state of emotional hyper-reactivity coupled with reduced top-down regulation, thereby increasing impulsivity and susceptibility to crises.

Insomnia contributes to feelings of hopelessness and entrapment. Persistent difficulty in falling asleep or maintaining sleep fosters beliefs of uncontrollability and despair. These perceptions align closely with cognitive models of suicidality, wherein hopelessness and entrapment are central components. Nightmares exacerbate this process by repeatedly presenting individuals with imagery of defeat, death, or humiliation. Such experiences infiltrate waking life, reinforcing suicidal rumination and diminishing psychological resilience against suicidal behavior [22].

Biological evidence supplements these psychological models. Serotonin, a neurotransmitter involved in sleep regulation, impulse control, and mood stabilization, has long been implicated in suicidality. Dysregulation of the serotonergic system may therefore provide a common biological pathway [23]. Chronic insomnia is also associated with hyperactivation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, producing sustained cortisol secretion. This pattern mirrors findings in suicidal individuals, where heightened stress reactivity is a consistent feature. Circadian disruption destabilizes neurotransmitter release and neuroendocrine rhythms, impairing mood regulation and cognitive functioning [24]. Genetic studies point to clock gene polymorphisms as contributors to both sleep disturbance and suicide risk [25]. Taken together, these mechanisms suggest that sleep disturbance is closely intertwined with the processes underlying suicidality. While these findings support biologically and psychologically plausible pathways, most evidence remains correlational, and direct causal data are limited.

Another pathway deserving attention is the impact of poor sleep on decision-making. Sleep deprivation consistently impairs executive functioning, risk appraisal, and problem-solving capacity. In the context of a suicidal crisis, these deficits may tilt the balance toward acting on suicidal thoughts rather than seeking help. Similarly, disrupted sleep diminishes reward sensitivity, which may blunt the protective effects of social support or pleasurable activities. Mechanistic models that combine emotional dysregulation, cognitive impairment, and biological dysrhythmia provide a more comprehensive account of how sleep directly modulates suicide risk.

2.6. Why Psychiatry Sidelines Sleep

Despite the breadth of evidence, psychiatry has been slow to integrate sleep into suicide prevention. The neglect is rooted in historical, structural, and cultural factors. This marginalization is not accidental but reflects the legacy of psychiatric nosology. Since the earliest editions of the DSM, sleep problems were consistently categorized as ancillary criteria, bundled into the broader construct of “neurovegetative symptoms.” As a result, clinicians were implicitly trained to view sleep disturbance as an epiphenomenon of depression, bipolar disorder, or anxiety rather than as an independent clinical entity. This framing has contributed to decades of underrecognition and under-treatment.

Sleep disturbances have historically been regarded as neurovegetative symptoms within diagnostic frameworks, often considered secondary manifestations of major psychiatric syndromes rather than as primary targets for treatment. Instruments used for assessing suicide risk seldom incorporate inquiries about sleep, thereby influencing clinician practices through omission [26]. The training in sleep medicine provided during psychiatric residency remains minimal, leaving psychiatrists inadequately prepared to diagnose or manage common sleep disorders. Additionally, structural divisions within medicine exacerbate this issue; sleep medicine originated predominantly within neurology and pulmonology, focusing on conditions such as apnea and narcolepsy, which has discouraged psychiatry from assuming responsibility in this domain.

Practical barriers reinforce this neglect. Sleep complaints are sometimes dismissed by clinicians as nonspecific or “lifestyle-related,” while patients themselves may underreport them, believing that poor sleep is a normal consequence of stress or aging. Stigma plays a role as well: individuals may hesitate to disclose nightmares or circadian difficulties, perceiving them as trivial compared to hallucinations or severe mood symptoms. Such dynamics perpetuate a cycle where both parties tacitly minimize the importance of sleep.

Finally, systemic pressures are significant. During brief clinical encounters, psychiatrists typically focus on immediate safety concerns, psychotic symptoms, and mood stabilization. Sleep may be observed but is rarely examined with the same thoroughness. Over time, this has become a standardized practice, fostering a culture in which sleep is recognized but seldom addressed proactively.

The consequence is a persistent blind spot in psychiatric care. By sidelining sleep, psychiatry not only overlooks an accessible marker of suicide risk but also misses an opportunity to deploy interventions that are evidence-based, low-cost, and acceptable to patients. In effect, the structural neglect of sleep sustains a gap between what research demonstrates and what practice delivers, delaying the integration of one of the most modifiable risk factors in suicide prevention.

A concise summary of the evidence linking sleep disturbances to suicidality, categorized by sleep domain and predominant study design, is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of representative evidence linking major sleep disturbances to suicidality, categorized by sleep domain and predominant study design.

3. Clinical Opportunities

Integrating sleep into psychiatric care is both feasible and necessary. Assessing sleep requires little more than a structured inquiry. Validated instruments such as the Insomnia Severity Index or Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index can be administered in minutes, while single standardized questions can highlight risk [27]. In clinical practice, sleep assessment can be integrated into suicide risk evaluation through simple, scalable steps. For example, brief questionnaires such as the PSQI or ISI can be included in standard intake assessments alongside mood and substance-use screening. Tracking sleep changes longitudinally—through clinician notes, patient self-reports, or wearable data—may help identify early warning signs that precede suicidal crises. Electronic medical records could include specific sleep-related fields within structured risk-assessment templates, ensuring that sleep quality and circadian stability are monitored systematically rather than informally. These measures require minimal additional time yet can provide valuable clinical insight into risk trajectories. Repeated assessments across visits allow clinicians to detect changes in sleep patterns that may precede suicidal crises, sometimes earlier than changes in mood or explicit ideation.

The treatment of sleep disturbances is similarly accessible. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) remains the first-line approach; it can be delivered through brief (four-to-six session) modules or digital and group formats that enhance scalability and patient engagement [28]. Imagery rehearsal therapy (IRT), typically involving several weekly sessions of guided nightmare rescripting, has demonstrated reductions in nightmare distress and frequency, with indirect evidence of decreased suicidal ideation through improved sleep continuity and emotion regulation.

Chronotherapeutic interventions such as bright-light therapy—most often administered in the morning for 20–40 min—sleep phase adjustments, and structured activity schedules aim to realign circadian rhythms and support mood stabilization [29]. Melatonin, commonly prescribed in low evening doses (1–5 mg), may complement behavioral strategies by promoting circadian realignment. Although these treatments are supported by robust data on sleep and mood improvements, their effects on suicidal outcomes remain largely indirect, highlighting the need for dedicated trials to confirm causal benefits.

Pharmacological options are available; however, they are not the sole tools. The emphasis is not on the necessity for psychiatry to invent new treatments, but on its consistent utilization of existing ones.

Sleep also functions as a dynamic and observable indicator of risk. Unlike mood, which may be concealed, alterations in sleep patterns are often readily apparent to both patients and their families. A sudden resurgence of nightmares, deterioration in insomnia, or abrupt changes in circadian rhythm may serve as early warning signs. In certain instances, these indicators precede the development of suicidal ideation, thereby offering a critical window for intervention. The use of digital technologies enhances this potential. Wearable devices and smartphone applications are capable of continuously and passively monitoring sleep duration, timing, and quality [30]. The integration of such data into predictive models may enable clinicians to identify escalating risks in real time.

Despite the feasibility of sleep interventions, barriers to implementation persist. Clinicians often cite limited training, time constraints, and lack of referral pathways to sleep specialists as reasons for neglecting sleep. Patients themselves may minimize sleep problems, viewing them as inevitable byproducts of stress or psychiatric illness.

Several factors help explain why psychiatric practice has been slow to integrate sleep assessment despite the growing evidence base. Limited training in sleep medicine during residency, the tendency to prioritize acute symptom management over lifestyle factors, and the historical division between psychiatry and other specialties such as neurology and pulmonology have all contributed to this inertia. Structural constraints—including short consultation times and insufficient referral pathways—further discourage clinicians from addressing sleep systematically. Recognizing and addressing these barriers is essential for translating research evidence into everyday clinical routines.

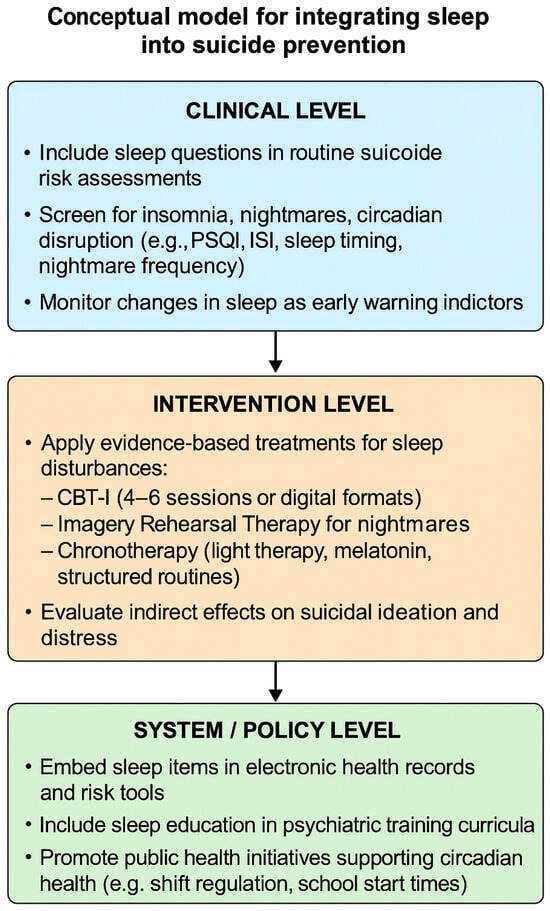

Addressing these barriers requires system-level strategies, such as embedding sleep modules into psychiatric residency curricula, integrating digital CBT-I platforms into outpatient clinics, and including sleep metrics in electronic health record templates for suicide risk assessment. These practical steps transform abstract recommendations into routine practice. Figure 1 provides a concise visual summary of the proposed framework, outlining how sleep-related assessment and interventions can be embedded within suicide prevention efforts at multiple levels of practice.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for integrating sleep into suicide prevention.

The model outlines three complementary levels for integration: clinical (routine assessment and monitoring), intervention (targeted management of sleep disturbances), and system/policy (structural and educational implementation). Together, these levels provide a practical framework for translating evidence into psychiatric and public health practice.

4. Future Directions

The path forward necessitates action across multiple levels. Research should advance beyond mere correlational studies to encompass interventional designs. Randomized controlled trials are essential to determine whether direct treatment of insomnia, nightmares, and circadian misalignment can effectively reduce suicidal outcomes. Preliminary studies suggest that improving sleep may reduce suicidal ideation, but evidence regarding suicide attempts and mortality remains scarce and methodologically heterogeneous.

Although the association between sleep disturbance and suicidality is well established, current evidence remains largely correlational. Few randomized trials have directly examined whether improving sleep reduces suicide attempts or mortality, and existing data are limited by sample size and methodological variability. Recognizing these gaps underscores the need for rigorous interventional and longitudinal studies to clarify causality and optimize clinical translation. Should such trials establish causal effects, the case for integrating sleep interventions into suicide prevention strategies will be unequivocal. Additionally, predictive models of suicidality must incorporate both subjective and objective sleep metrics. Machine learning techniques, which already demonstrate potential in assessing suicide risk, are expected to benefit substantially from the inclusion of sleep data.

Translational research should also bridge laboratory findings with clinical outcomes. Neuroimaging studies of sleep deprivation and circadian misalignment, for example, highlight alterations in prefrontal–limbic connectivity and serotonergic signaling, both of which are implicated in suicidal crises. Biomarker studies could complement these findings by integrating inflammatory and hormonal indicators with sleep metrics to build multidimensional risk profiles. Such translational approaches would clarify the mechanisms linking sleep disturbance and suicidality, facilitating the development of targeted interventions and personalized treatment algorithms.

Training and education must be reformed. Psychiatry should reclaim sleep as a domain of expertise. Residency programs must provide trainees with fundamental skills to assess and treat common sleep disorders. Continuing education should address existing gaps among practicing clinicians. Policy measures are equally vital. Suicide prevention guidelines should explicitly incorporate sleep as a standard component of risk assessment. Public health campaigns should frame sleep as a fundamental pillar of mental health, alongside exercise and nutrition. Schools should synchronize schedules with adolescent circadian biology, and workplaces should implement policies that respect circadian health, particularly for shift workers. Such measures could diminish risks not only within clinical populations but across society.

Progress will also depend on interdisciplinary and international collaboration. Psychiatrists, neurologists, sleep specialists, and primary care providers should work together to standardize assessment protocols that include sleep as a routine component. On a global scale, integrating sleep questions into large epidemiological surveys on suicide could generate cross-cultural data, illuminating how cultural, environmental, and economic factors moderate the sleep–suicide relationship. Such efforts would ensure that recommendations are not restricted to high-income countries but are adaptable to diverse healthcare systems worldwide.

A further frontier lies in digital phenotyping. Passive data streams from smartphones and wearables can capture sleep–wake regularity, nocturnal awakenings, and circadian drift in real time. Early studies suggest that these digital markers may predict suicidal crises days before they become clinically evident. Coupled with ecological momentary assessment of mood, such tools could generate dynamic risk profiles that surpass static questionnaires. Ethical considerations, including privacy and data governance, must be addressed, but the potential for early detection and intervention is unprecedented. Integrating sleep into digital suicide prevention aligns with a broader move toward precision psychiatry.

Finally, implementation science must guide the translation of evidence into practice. Even the most robust findings risk being underutilized if not embedded into clinical pathways. Pragmatic trials in real-world settings—community clinics, schools, workplaces—can test the feasibility of integrating sleep assessment and intervention into routine care. At the policy level, national suicide prevention strategies should explicitly allocate funding for sleep-focused initiatives, including training modules, public awareness campaigns, and technology-supported monitoring. Without structural support, the integration of sleep into suicide prevention risks remaining aspirational rather than transformative.

5. Conclusions

Viewing sleep as a transdiagnostic domain allows psychiatry to bridge biological, psychological, and social perspectives within a single, coherent framework. Sleep disturbance does not belong to any one diagnostic category; it shapes emotion, cognition, and social interaction across virtually all mental disorders. Its neglect, therefore, represents not only a clinical omission but a conceptual limitation in how psychiatry defines and measures vulnerability.

The evidence accumulated over the past two decades indicates that insomnia, nightmares, and circadian disruption are consistent and potentially modifiable correlates of suicidality. While most findings are observational—cross-sectional or longitudinal—rather than causal, their convergence across diverse diagnoses, ages, and cultures points to a robust and clinically meaningful association. Randomized trials targeting sleep have largely focused on symptom reduction, but the indirect benefits on suicidal ideation and emotional regulation suggest that treating sleep disturbance could reduce risk trajectories even in the absence of direct anti-suicidal effects.

From a practical standpoint, sleep offers psychiatry a rare combination of feasibility and impact. It can be evaluated quickly through brief validated tools such as the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) or the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), incorporated into intake assessments without extending visit duration, and monitored longitudinally using patient reports or digital data. Sleep changes often precede shifts in mood or explicit suicidal ideation, providing clinicians with a tangible early warning system.

Treatment options are equally accessible. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) remains the gold standard, supported by robust evidence for improving sleep and emotional regulation. Imagery rehearsal therapy (IRT) can effectively address recurrent nightmares, while circadian-based approaches—such as light therapy, melatonin, and structured activity scheduling—help realign biological rhythms and stabilize mood. These interventions are inexpensive, acceptable to patients, and compatible with existing psychiatric treatment plans, making them ideal candidates for integration into suicide prevention pathways.

To achieve this integration, psychiatry must move beyond passive acknowledgment toward structural incorporation. Residency programs should include basic training in sleep assessment and management; electronic health records could contain standardized fields for sleep variables; and national suicide prevention guidelines should explicitly reference sleep as a modifiable component of risk. On a broader scale, public health policies that promote adequate sleep—through school start-time reform, workplace protections for shift workers, and public education—could yield population-level benefits in mental health and suicide prevention.

The challenge ahead is primarily cultural, not technological. Sleep has been historically relegated to the margins of psychiatric practice because it sits at the crossroads of multiple disciplines—neurology, pulmonology, psychology—and has lacked clear ownership. Yet reclaiming it is both realistic and overdue. Recognizing sleep as a cornerstone of mental health reframes suicide prevention from a narrow focus on mood and cognition to a more integrated and humane model of care.

By embedding sleep into the daily fabric of psychiatric evaluation—through systematic screening, targeted intervention, and institutional training—psychiatry can act on one of the most consistent, modifiable, and biologically grounded indicators of suicide risk. Doing so would not only improve diagnostic precision and clinical outcomes but also align the discipline with a growing body of evidence calling for a holistic, biologically informed, and person-centered approach to suicide prevention.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO. Suicide Worldwide in 2019: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Baldini, V.; Gnazzo, M.; Varallo, G.; Atti, A.R.; De Ronchi, D.; Fiorillo, A.; Plazzi, G. Inflammatory markers and suicidal behavior: A comprehensive review of emerging evidence. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2025, 24, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Borges, G.; Bromet, E.J.; Cha, C.B.; Kessler, R.C.; Lee, S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol. Rev. 2008, 30, 133–154. [Google Scholar]

- Baldini, V.; Gnazzo, M.; Maragno, M.; Biagetti, R.; Stefanini, C.; Canulli, F.; Varallo, G.; Donati, C.; Neri, G.; Fiorillo, A.; et al. Suicidal risk among adolescent psychiatric inpatients: The role of insomnia, depression, and social-personal factors. Eur. Psychiatry 2025, 68, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, A.; Osborn, D.; King, M.; Erlangsen, A. Effects of suicide bereavement on mental health and suicide risk. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawton, K.; Saunders, K.E.A.; O’Connor, R.C. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet 2012, 379, 2373–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naghavi, M.; Global Burden of Disease Self-Harm Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality. BMJ 2019, 364, l94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stack, S. Suicide: A 15-year review of the sociological literature. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2000, 35, 202–216. [Google Scholar]

- Bernert, R.A.; Joiner, T.E. Sleep disturbances and suicide risk: A review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2007, 3, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Kovacs, M.; Weissman, A. Hopelessness and suicidal behavior. JAMA Psychiatry 1975, 32, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, J.J.; Waternaux, C.; Haas, G.L.; Malone, K.M. Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, W.V.; Black, C.G. The link between suicide and insomnia: Theoretical mechanisms. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2013, 15, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, V.; Gnazzo, M.; Rapelli, G.; Marchi, M.; Pingani, L.; Ferrari, S.; De Ronchi, D.; Varallo, G.; Starace, F.; Franceschini, C.; et al. Association between sleep disturbances and suicidal behavior in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1341686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørngaard, J.H.; Bjerkeset, O.; Romundstad, P.; Gunnell, D. Sleeping problems and suicide in 75,000 Norwegian adults: A 20-year follow-up. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 131, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woznica, A.A.; Carney, C.E.; Kuo, J.R.; Moss, T.G. The insomnia and suicide link: Toward an enhanced understanding of this relationship. Sleep Med. Rev. 2015, 22, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigeon, W.R.; Pinquart, M.; Conner, K. Meta-analysis of sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2012, 73, e1160–e1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Luo, X.; Song, L.; Fan, T.; Huang, C.; Shen, Y. The association between insomnia and suicide attempts among Chinese adolescents: A prospective cohort study. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.M.; Brower, K.J.; Zucker, R.A. Sleep problems, suicidal ideation, and self-harm behaviors in adolescence. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 45, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedström, A.K.; Hössjer, O.; Bellocco, R.; Ye, W.; Lagerros, Y.T.; Åkerstedt, T. Insomnia in the context of short sleep increases suicide risk. Sleep 2021, 44, zsaa245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Michelsen, M.E.; Erlangsen, A.; Høier, N.K.; Jennum, P.J.; Nordentoft, M.; Madsen, T. Sleep disturbances in early adolescents and risk of later suicidality: A national prospective cohort study. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2025, 25, 100580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.M.; Baker, J.C.; Bryan, C.J. Prospective associations of insomnia and nightmares with suicidal behavior among primary care patients. Fam. Syst. Health 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, J.; Rosenheck, R.; Sun, B.; Liu, J.; Shen, Y.; Yuan, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, L.; et al. Prevalence and correlates of suicide risk among non-psychiatric inpatients in a general hospital in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 347, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saguin, E.; Feingold, D.; Sipahimalani, G.; Quiquempoix, M.; Roseau, J.-B.; Remadi, M.; Annette, S.; Guillard, M.; Van Beers, P.; Lahutte, B.; et al. PTSD symptom severity associated with sleep disturbances in military personnel: Evidence from a prospective controlled study with ecological recordings. Depress. Anxiety 2025, 42, 8011375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Pruiksma, K.E.; Taylor, D.J.; Khazem, L.R.; Baker, J.C.; Young, J.; Bryan, C.J.; Wiley, J.; Brown, L.A. Rates of sleep disorders based on a structured clinical interview in U.S. active-duty military personnel with acute suicide risk. Behav. Sleep Med. 2025, 23, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-T.; Lai, C.-H.; Perng, H.-J.; Chung, C.-H.; Wang, C.-C.; Chen, W.-L.; Chien, W.-C. Insomnia as an independent predictor of suicide attempts: A nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandman, N.; Valli, K.; Kronholm, E.; Revonsuo, A.; Laatikainen, T.; Paunio, T. Nightmares: Risk factors and their association with subjective well-being. J. Sleep Res. 2015, 24, 547–556. [Google Scholar]

- Krakow, B.; Hollifield, M.; Johnston, L.; Koss, M.; Schrader, R.; Warner, T.D.; Tandberg, D.; Lauriello, J.; McBride, L.; Cutchen, L.; et al. Imagery rehearsal therapy for chronic nightmares in sexual assault survivors with PTSD: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001, 286, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, M.J.; Rego, S.A.; Asnis, G.M. Sleep disturbances in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder: Epidemiology, impact and approaches to management. CNS Drugs 2006, 20, 567–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belleville, G.; Dubé-Frenette, M.; Rousseau, A. Efficacy of imagery rehearsal therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy in sexual assault victims with posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J. Trauma Stress 2018, 31, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.E.; Duong, H.T. The prospective association between sleep deprivation and depression among adolescents. Sleep 2014, 37, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).