Abstract

Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM) face a significantly increased risk of developing disordered eating behaviors (DEBs), a phenomenon that includes the deliberate omission of insulin, commonly referred to as diabulimia. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine the prevalence of diabulimia in adolescents with T1DM and consolidate the scientific evidence on this issue. Following PRISMA guidelines, observational studies published in English and Spanish involving adolescents aged 10 to 19 were identified through comprehensive searches in SCOPUS, LILACS, PubMed, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. After rigorous screening and eligibility assessment, 13 studies were included. Data were extracted independently, and meta-analyses were performed using random-effects models. Reported prevalence rates of DEB in T1DM varied widely among studies, ranging from 20.8% to 48%. The pooled prevalence in the final meta-analytic model was 11% (95% CI: 9–13%), with prevalence substantially higher in females (45%) than males (26%). These findings highlight not only the elevated risk of DEB and diabulimia among adolescents with T1DM but also considerable gender differences likely shaped by psychological, sociocultural, and biological factors. The lack of standardized diagnostic criteria for diabulimia remains a barrier to clinical management. Early detection and gender-sensitive preventive strategies are crucial for reducing complications and improving the quality of life in this vulnerable population.

1. Introduction

Diabetes Mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic disease characterized by high blood glucose levels, causing serious damage to the body [1]. It is known that approximately 830 million people suffer from DM, with a high prevalence in low- and middle-income countries, of whom 1.1 million are children and adolescents diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus [2]. This subtype is particularly known as juvenile or insulin-dependent diabetes, in which the pancreas produces little or no insulin on its own [3]. On the other hand, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) occurs when the body becomes resistant to insulin or its production is insufficient [4].

There is evidence of an association between DM and eating disorders (EDs) [5,6]. Young people with T1DM are at a higher risk of developing EDs, with severe short- and long-term negative effects [7]. The prevalence of EDs in adolescents with T1DM is significantly higher than in the general population, where EDs are expected to affect around 4% [8]. According to Philpot, a higher prevalence of disordered eating behaviors (39.3% vs. 32.5%) and eating disorders (7.0% vs. 2.8%) was found in adolescents with T1DM compared to their peers without T1DM. Moreover, other studies have reported that adolescence and gender increase the risk of developing EDs. Data show that between 10% and 30% of females with T1DM develop EDs. Furthermore, reported prevalence in adolescents with T1DM is as high as 30% to 50% in adolescent females and approximately 9% in males [9]. Additionally, it has been found that 60% of people with T1DM restrict insulin intake [10].

Omitting or restricting insulin leads to weight loss because glucose is not stored as fat but is instead excreted from the body. People who skip insulin have a threefold higher risk of premature death compared to those who follow the prescribed treatment. In the same vein, the prognosis is worse in individuals with comorbid conditions. Some of the clinical characteristics of an eating disorder (ED) associated with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM) include: distorted body image, weight loss or gain, purging behaviors, binge eating, worsening of glycemic and metabolic control, and hospitalization for diabetic ketoacidosis. These manifestations are often accompanied by feelings of guilt and self-loathing.

The literature distinguishes between the presence of T1DM and the clinical or subclinical symptoms of eating disorders (EDs), such as disordered eating behaviors. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) provides diagnostic criteria for pica, rumination disorder, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. Among these, the criteria for anorexia, bulimia, and binge eating disorder form a mutually exclusive classification framework. Disordered eating behaviors encompass a wide range of problematic eating patterns and distorted attitudes toward food, body weight, shape, and appearance.

In this context, the term diabulimia has emerged with various interpretations. According to the National Eating Disorders Association, diabulimia refers to any person with insulin-dependent diabetes who deliberately omits or restricts insulin. Other definitions, however, suggest that diabulimia involves the coexistence of diabetes and a diagnosed eating disorder. A third interpretation focuses on the overlap between diabetes and bulimia [10,11,12]. Nevertheless, diabulimia is not currently recognized as an official diagnosis in standard classification systems. Instead, its description remains problematic due to the lack of a clear distinction between a symptom (such as purging behavior) and a set of clinical or subclinical manifestations.

It is important to note that compensatory behaviors are common clinical features in eating disorders. However, the most appropriate term to describe this phenomenon is eating disorder in T1DM [10], as it better reflects the unique clinical presentation in individuals with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus.

The etiology of eating disorders (EDs) in type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is multifactorial and includes genetic vulnerability [13,14,15,16]. Individual risk factors include elevated body mass index (BMI), intense concern with weight control and glycemic levels [17,18], the association between weight gain and insulin, high self-demand, and body dissatisfaction [18]. Predisposing factors for this condition include pronounced personality traits such as excessive perfectionism, emotional instability, low self-esteem, and interpersonal difficulties [13]. Moreover, sociocultural and family factors also play a significant role in the development of diabulimia, such as body image expectations, social pressure, and puberty, which represents a period of greater vulnerability due to hormonal and physical changes, like weight gain, that intensify concerns about body image [17].

The objective of the present study was to determine the prevalence of diabulimia in adolescents through a systematic review and meta-analysis of the scientific literature, with the aim of consolidating the existing evidence on this disorder.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection Criteria

The research was conducted following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [19] (The PRISMA checklist is available in Supplementary Materials). It was registered in PROSPERO with the number 1,109,541. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were established according to the CoCoPop format (Condition, Context, and Population), recommended for prevalence or incidence studies of a condition [20].

Condition: Disordered eating behaviors and type 1 diabetes mellitus were considered, according to the diagnostic definitions and classifications of the DSM-5R [1]. Due to theoretical and clinical discrepancies, no specific definition of diabulimia was used.

Context: No restrictions were applied regarding the context.

Population: Adolescent participants aged 10 to 19 years of any nationality were included. The WHO definition of adolescence was adopted [1].

Study types: Observational studies (cross-sectional and cohort) aiming to establish prevalence were considered. Original articles published in English and Spanish were included.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

The databases considered in this study were SCOPUS, LILACS, PubMed/Medline, Web of Science, and PsycInfo. To mitigate the potential risk of exclusion, grey literature was also considered by extending the search to OpenGrey and GreyNet. However, no results were obtained from this search. Both Spanish and English terms were included, identified based on Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS) and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). The search was conducted using Boolean operators such as AND and OR to improve the precision of the results. See Appendix A for a detailed description of the search strategy.

2.3. Procedure and Data Extraction

The review was independently conducted by two researchers (G.C. and C.S.). To enhance transparency in the selection and data extraction processes, we now report inter-reviewer reliability using Cohen’s kappa coefficient. The results indicate substantial agreement, with κ = 0.84 for study selection and κ = 0.88 for data extraction, supporting the reproducibility and methodological rigor of the review.

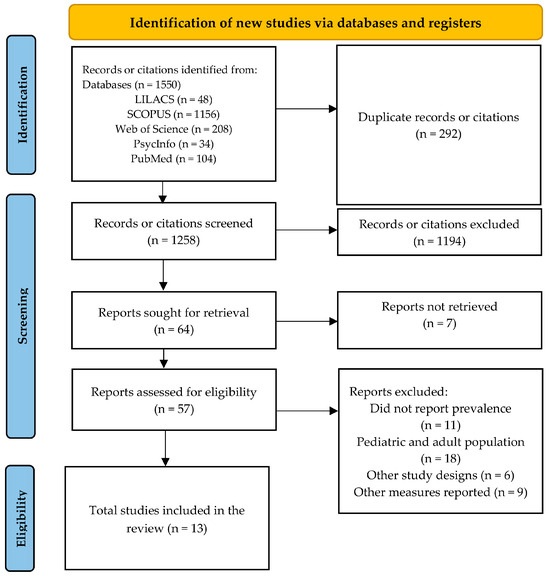

It was structured in three phases as illustrated in Figure 1, and an Excel matrix was used to record each study’s information including: author, country where the study was conducted, year, journal of publication, study objective, diabulimia definition used in each study, total sample, sample of males and females, age, prevalence results, prevalence assessment instrument, reported reliability of the instrument, and reported prevalence of the condition. In the first identification phase, 1550 studies were included for review. In the second phase, after duplicate removal and screening, a total of 57 studies were selected for relevance assessment. Finally, in the third phase, 13 studies meeting all inclusion criteria were included. Studies were only included when full-text articles were available. The retrieval date was 26 January 2025. Results were exported to the Rayyan web application in RIS format, including metadata such as author, journal, DOI, and abstract [21].

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram.

2.4. Data Analysis

Ten studies were considered for the total prevalence meta-analysis; those reporting the incorporation of measurement instruments other than the reviewed Diabetes Eating Problem Survey (DEPS) [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30] were excluded. For the gender-specific prevalence meta-analysis, seven studies were included, with one excluded due to small sample size [23].

The analysis was performed using Jamovi software version 2.3.28 and the Major package. A random-effects model was employed, which does not assume homogeneity a priori and attributes variability to differences between studies and sampling error. The restricted maximum likelihood estimator model was used, with raw proportions as the effect size measure. Heterogeneity (I2) was reported, with Higgins and Thompson (2002) interpreting I2 values as low heterogeneity (25%), moderate heterogeneity (50%), and high heterogeneity (75%).

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

The evaluation of the methodological quality of the included studies revealed that, in general, they meet the fundamental criteria established for prevalence research. Most of the studies used validated psychometric instruments, with the DEPS-R being the most frequently employed, and reported acceptable reliability coefficients in several investigations (ranging from 0.81 to 0.86), ensuring internal consistency. The samples are clearly defined, with well-delineated age ranges (between 10 and 19 years), and although sample sizes vary considerably from 50 to 395 participants they are considered appropriate for the specific clinical context. Additionally, all studies specify the country, the type of instrument used, and clearly report overall and sex-specific prevalence rates. Overall, according to the criteria of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), these studies demonstrate acceptable methodological quality to be included in a prevalence meta-analysis.

The studies were conducted in the last five years. Of the 13 selected studies, 23.1% (n = 3) were conducted in Italy in 2019 [14,31,32], and 23.1% (n = 3) were conducted in Turkey [26,28,33]. The remaining studies took place in the following countries: one study in Australia [23], one in Korea [25], one in Denmark [24], one in Egypt [29], one in Ethiopia [22], one in Israel [27], and one in Tunisia [30].

Table 1 describes the main characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review. A total of 53.8% (n = 7) aimed to determine the prevalence of disordered eating behaviors in T1DM [14,23,24,25,28,30], 38.5% (n = 5) of the studies sought to relate disordered eating behaviors with other clinical variables in adolescents diagnosed with T1DM [22,26,29,30,31], and 7.7% (n = 1) evaluated prevalence and risk factors [27].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Selected Studies.

Regarding the definition of diabulimia considered in the studies, 84.6% (n = 11) made no mention of the term; they distinguished between eating disorders as clinical symptoms and disordered eating behaviors as subclinical symptoms [14,22,23,24,25,26,27,29,30,31]. The remaining 15.4% (n = 2) reported the following definitions: Diabulimia is considered a specific eating disorder in people with diabetes, classified under the drug abuse group to ensure an unspecified eating disorder/weight loss according to the DSM-5 [28]. Another conceptualization defines it as the behavior of omitting or reducing insulin dosage to lose weight in people diagnosed with T1DM [33].

Regarding the participants’ age, the criterion of adolescence ranging from 10 to 19 years (WHO, 2024) [1] was met. The mean age of participants was 15.2 years (SD = 0.98). All studies included mixed samples (female and male) diagnosed with T1DM, with disease duration ranging from 6 months to 1 year.

The most commonly used screening instrument was the Diabetes Eating Problem Survey-Revised (DEPS-R), reported by 76.9% (n = 10) of the studies [14,22,23,24,25,27,28,31,32,33]. The scale consists of 16 items, with a Likert response scale from 0 to 6 points (0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = usually, 5 = always). Scores greater than or equal to 20 points suggest the presence of disordered eating behaviors. Other screening instruments used were the Eating Attitudes Test [26,30], The Binge Eating Scale Arabic version [29], and the Bulimic Investigatory Test Edinburgh [30].

Regarding the reported reliability of the instruments, the most used measure was Cronbach’s alpha, used in 46% (n = 6) of the studies [14,25,27,32,33]. The other studies did not report this value [23,24,26,29,30,34].

3.2. Prevalence of Disordered Eating Behaviors in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM)

3.2.1. Overall Prevalence

The reported overall prevalence rates varied across studies, ranging from 20.8% to 48% [23,24]. In most studies, the overall prevalence rates were found to be higher in women. The heterogeneity of the studies (I2) was initially 99.53%. Based on the results of the sequential algorithm to improve the proportional model (Table 2), algorithms were considered to reduce the I2 threshold (to below 25%). This analysis involved excluding studies that included sample sizes below the recommended level (10:1, observations per item) or studies with large samples. In the final meta-analysis model, the overall prevalence was 11% (95% CI: 9–13%), with a heterogeneity of 0% [22,24,27]. The random-effects model and meta-analysis plots can be found in Appendix A.

Table 2.

Models.

3.2.2. Prevalence by Sex

Seven studies were included that reported the sample by sex and differentiated prevalence rates; in some cases, the calculation was made based on the information reported in the studies [14,22,23,24,28,31,32]. However, one study [23] was previously excluded due to the small total sample size (n = 50).

The meta-analysis of prevalence in males initially showed a study heterogeneity (I2) of 97.48%. Algorithms were applied to reduce the I2 threshold (below 25%). This analysis involved excluding studies with sample sizes below the recommended level (10:1, observations per item). As a result, three studies were excluded [24,32,34]. In the final meta-analysis model, the prevalence in males was 26% (95% CI = 22–30%), with a heterogeneity of 0% [14,22,31].

For the initial meta-analysis in females, the heterogeneity of the studies (I2) was initially 96.36%. Algorithms were also applied to reduce the I2 threshold (below 25%), involving the exclusion of studies with insufficient sample sizes (10:1, observations per item). Three studies were excluded [22,28,32]. In the final meta-analysis model, the prevalence in females was 45% (95% CI = 39–51%), with a heterogeneity of 8.84% [14,24,31]. The random-effects model and meta-analysis plots can be found in Appendix A.

4. Discussion

This systematic review highlights a high prevalence of disordered eating behaviors (DEB) generally among individuals with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus, emphasizing the complex interaction between the management of eating disorders and diabetes. Regarding the results, they indicate that the overall prevalence of disordered eating behaviors was 11%, based on ten studies included in the analysis. Likewise, the reported prevalence rates ranged from 20.8% to 48% across different studies, indicating considerable heterogeneity in the data [23,24]. On the other hand, in the analysis by sex, seven investigations were included that reported prevalence rates by gender, showing various calculations performed in each study. Thus, the analysis by sex showed considerable differences: in men, the final prevalence was 26%, with zero heterogeneity after using an algorithm to reduce heterogeneity. In contrast, in women, prevalence was 45% with moderate heterogeneity of 8.84%. Therefore, this suggests differences in psychological, sociocultural, and biological factors that significantly influence the development of eating disorders in relation to type 1 diabetes [14,22,31,34,35].

However, adolescents with T1DM are at a significantly higher risk of developing these disorders compared to their peers without diabetes, highlighting the importance of early detection. One of the most relevant findings in this research is the association between insulin omission and DKA (diabetic ketoacidosis), a phenomenon termed diabulimia. Unfortunately, this behavior is concerning due to the risk of critical complications, including impaired glycemic control, premature mortality, and recurrent episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis [31].

Indeed, the absence of systematized diagnostic criteria for diabulimia presents an obstacle in clinical practice, as current classification systems do not clearly distinguish between insulin omission as a purging behavior [14]. The data analysis reveals gender differences in prevalence, with a higher occurrence in adolescent females compared to males. Sociocultural factors, such as pressure to meet beauty standards, contribute to this disparity. Although the increasing recognition of DEB in males suggests that traditional gender norms have led to underestimation of these cases in boys [14].

Furthermore, the etiology of DEB in T1DM is multifactorial and encompasses biological, sociocultural, and psychological factors. Among individual risk factors, high body mass index (BMI), low self-esteem, extreme self-demanding personality, and emotional instability stand out [32]. Even sociocultural influences, such as body image ideals promoted by social media, increase vulnerability to DEB. At the family level, parental pressure for strict dietary and glucose control may unfortunately encourage the development of disordered eating patterns as a coping mechanism [13]. However, the lack of effective interventions with a gender- and age-specific perspective represents another challenge for the prevention and treatment of DEB, especially in adolescents with T1DM, as adolescence is a crucial stage marked by social, psychological, and hormonal changes that may increase the risk of developing eating disorders.

Regarding prevention, it is important to promote intervention strategies focused on the medical community, patients, and their families. Raising awareness about the overlap between diabetes and eating disorders can improve recognition of warning signs and facilitate timely referral to specialists. Additionally, future studies should focus on validating defined diagnostic criteria for diabulimia, developing screening instruments, and evaluating the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions [22].

In conclusion, it is important to increase the training of health professionals on this issue to improve clinical care and prevention. Implementing educational campaigns and using digital platforms to disseminate information about DEB in T1DM could be key strategies to reduce the prevalence of these conditions and improve the quality of life for affected individuals [31].

5. Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM) exhibit a substantial prevalence of disordered eating behaviors, including insulin omission or restriction commonly known as diabulimia. The overall prevalence was estimated at 11%, with significantly higher rates among females compared to males. These findings highlight the need for increased awareness and early detection of disordered eating behaviors in this high-risk group. The multifactorial etiology encompassing psychological, sociocultural, and biological influences emphasizes the importance of comprehensive prevention and intervention strategies tailored to the needs of adolescents with T1DM.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, although Jamovi [36] provided a user-friendly platform for meta-analytic procedures, it does not currently support certain advanced diagnostics such as influence analysis or regression-based approaches to publication bias (e.g., Egger’s test, PET-PEESE). Consequently, the depth of bias and heterogeneity assessment may have been restricted compared to analyses performed in R [37]. Second, although sex/gender differences were observed and are clinically relevant, a systematic moderator analysis could not be performed due to data limitations and software constraints, which limits the ability to comprehensively evaluate effect modification [38]. Third, although publication bias was visually explored, the absence of formal statistical tests increases the potential for unaccounted small-study effects. Finally, while the final random-effects model (Model 6) was selected based on methodological thresholds to reduce heterogeneity, this decision was post hoc and may have introduced an element of subjectivity in model specification. Despite these limitations, the study provides a transparent and rigorous synthesis of current evidence, highlighting important clinical and research implications.

The absence of standardized diagnostic criteria for diabulimia presents a barrier for clinical recognition and effective management. Future research should focus on developing consensus definitions, validated screening tools, and evaluating the effectiveness of targeted interventions. Enhanced training for healthcare professionals, as well as educational initiatives directed at families and patients, is essential to reduce the risk of severe complications and improve quality of life in adolescents living with T1DM.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/psychiatryint6040148/s1, Table S1: The PRISMA Checklist.

Author Contributions

Contribution to the conception and design: A.R.; Contribution to data collection: c Contribution to data analysis and interpretation: A.R., V.Q.-C. and C.S.; Drafting and/or revising the article: G.C., C.S., A.R. and V.Q.-C.; Approval of the final version for publication: G.C., C.S., A.R. and V.Q.-C.; Obtaining authorization for the scale: A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financed by the Universidad Politécnica Salesiana Sede Cuenca, Ecuador.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this research are publicly available and can be obtained by emailing the first author of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, Ecuador, and especially to Juan Cárdenas Tapia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Search Strategy

| Database | Search Terms | n |

| LILACS | (Diabulimia OR “Trastornos de Alimentación y de la Ingestión de Alimentos” OR “Trastorno Alimentario” OR “Trastornos Alimentarios” OR “Trastornos Alimentarios y de la Ingestión de Alimentos” OR “Trastornos de Alimentación” OR “Trastornos de la Conducta Alimentaria” OR “Trastornos de la Ingesta de Alimentos” OR “Trastornos de la Ingestión de Alimentos” OR “Trastornos del Apetito” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Tipo 1” OR “Diabetes Autoinmune” OR “Diabetes Mellitus 1 Insulinodependiente” OR “Diabetes Mellitus con Propensión a la Cetosis” OR “Diabetes Mellitus de Inicio Súbito” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Inestable” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Insulino Dependiente” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Insulinodependiente” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Juvenil Inicial” OR “Diabetes Tipo 1” OR DMID) AND (Adolescente OR Adolescencia OR Adolescentes OR Joven OR Jóvenes OR Juventud) | 48 |

| SCOPUS | (“Feeding Eating Disorders” OR “Eating Feeding Disorders” OR “Appetite Disorders” OR “Appetite Disorder” OR “Eating Disorders” OR “Disorder Eating” OR “Disorders Eating” OR “Eating Disorder” OR “Feeding Disorders” OR “Disorder Feeding” OR “Disorders Feeding” OR “Feeding Disorder” OR Diabulimia) AND (“Diabetes Mellitus Type 1” OR “Type 1 Diabetes” OR “Diabetes Type 1” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Insulin Dependent” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Insulin Dependent” OR “Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Juvenile Onset” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Juvenile Onset” OR “Juvenile Onset Diabetes Mellitus” OR IDDM OR “Diabetes Mellitus Type I” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Sudden Onset” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Sudden Onset” OR “Sudden Onset Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Insulin Dependent 1” OR “Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus 1” OR “Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus 1” OR “Juvenile Onset Diabetes” OR “Diabetes Juvenile Onset” OR “Juvenile Onset Diabetes” OR “Diabetes Autoimmune” OR “Autoimmune Diabetes” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Brittle” OR “Brittle Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Ketosis Prone” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Ketosis Prone” OR “Ketosis Prone Diabetes Mellitus”) AND (Adolescent OR Adolescents OR Adolescence OR “Adolescents Female” OR “Adolescent Female” OR “Female Adolescent” OR “Female Adolescents” OR “Adolescents Male” OR “Adolescent Male” OR “Male Adolescent” OR “Male Adolescents” OR Youth OR Youths OR Teens OR Teen OR Teenagers OR Teenager) | 1156 |

| Web of Science | (“Feeding Eating Disorders” OR “Eating Feeding Disorders” OR “Appetite Disorders” OR “Appetite Disorder” OR “Eating Disorders” OR “Disorder Eating” OR “Disorders Eating” OR “Eating Disorder” OR “Feeding Disorders” OR “Disorder Feeding” OR “Disorders Feeding” OR “Feeding Disorder” OR Diabulimia) AND (“Diabetes Mellitus Type 1” OR “Type 1 Diabetes” OR “Diabetes Type 1” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Insulin Dependent” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Insulin Dependent” OR “Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Juvenile Onset” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Juvenile Onset” OR “Juvenile Onset Diabetes Mellitus” OR IDDM OR “Diabetes Mellitus Type I” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Sudden Onset” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Sudden Onset” OR “Sudden Onset Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Insulin Dependent 1” OR “Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus 1” OR “Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus 1” OR “Juvenile Onset Diabetes” OR “Diabetes Juvenile Onset” OR “Juvenile Onset Diabetes” OR “Diabetes Autoimmune” OR “Autoimmune Diabetes” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Brittle” OR “Brittle Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Ketosis Prone” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Ketosis Prone” OR “Ketosis Prone Diabetes Mellitus”) AND (Adolescent OR Adolescents OR Adolescence OR “Adolescents Female” OR “Adolescent Female” OR “Female Adolescent” OR “Female Adolescents” OR “Adolescents Male” OR “Adolescent Male” OR “Male Adolescent” OR “Male Adolescents” OR Youth OR Youths OR Teens OR Teen OR Teenagers OR Teenager) | 208 |

| PSYCINFO | (“Feeding Eating Disorders” OR “Eating Feeding Disorders” OR “Appetite Disorders” OR “Appetite Disorder” OR “Eating Disorders” OR “Disorder Eating” OR “Disorders Eating” OR “Eating Disorder” OR “Feeding Disorders” OR “Disorder Feeding” OR “Disorders Feeding” OR “Feeding Disorder” OR Diabulimia) AND (“Diabetes Mellitus Type 1” OR “Type 1 Diabetes” OR “Diabetes Type 1” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Insulin Dependent” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Insulin Dependent” OR “Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Juvenile Onset” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Juvenile Onset” OR “Juvenile Onset Diabetes Mellitus” OR IDDM OR “Diabetes Mellitus Type I” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Sudden Onset” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Sudden Onset” OR “Sudden Onset Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Insulin Dependent 1” OR “Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus 1” OR “Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus 1” OR “Juvenile Onset Diabetes” OR “Diabetes Juvenile Onset” OR “Juvenile Onset Diabetes” OR “Diabetes Autoimmune” OR “Autoimmune Diabetes” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Brittle” OR “Brittle Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Ketosis Prone” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Ketosis Prone” OR “Ketosis Prone Diabetes Mellitus”) AND (Adolescent OR Adolescents OR Adolescence OR “Adolescents Female” OR “Adolescent Female” OR “Female Adolescent” OR “Female Adolescents” OR “Adolescents Male” OR “Adolescent Male” OR “Male Adolescent” OR “Male Adolescents” OR Youth OR Youths OR Teens OR Teen OR Teenagers OR Teenager) | 34 |

| PubMed | (“Feeding Eating Disorders” OR “Eating Feeding Disorders” OR “Appetite Disorders” OR “Appetite Disorder” OR “Eating Disorders” OR “Disorder Eating” OR “Disorders Eating” OR “Eating Disorder” OR “Feeding Disorders” OR “Disorder Feeding” OR “Disorders Feeding” OR “Feeding Disorder” OR Diabulimia) AND (“Diabetes Mellitus Type 1” OR “Type 1 Diabetes” OR “Diabetes Type 1” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Insulin Dependent” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Insulin Dependent” OR “Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Juvenile Onset” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Juvenile Onset” OR “Juvenile Onset Diabetes Mellitus” OR IDDM OR “Diabetes Mellitus Type I” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Sudden Onset” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Sudden Onset” OR “Sudden Onset Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Insulin Dependent 1” OR “Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus 1” OR “Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus 1” OR “Juvenile Onset Diabetes” OR “Diabetes Juvenile Onset” OR “Juvenile Onset Diabetes” OR “Diabetes Autoimmune” OR “Autoimmune Diabetes” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Brittle” OR “Brittle Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Ketosis Prone” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Ketosis Prone” OR “Ketosis Prone Diabetes Mellitus”) AND (Adolescent OR Adolescents OR Adolescence OR “Adolescents Female” OR “Adolescent Female” OR “Female Adolescent” OR “Female Adolescents” OR “Adolescents Male” OR “Adolescent Male” OR “Male Adolescent” OR “Male Adolescents” OR Youth OR Youths OR Teens OR Teen OR Teenagers OR Teenager) | 104 |

References

- World Health Organization. Diabetes. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/health-topics/adolescent-health (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- World Health Organization. Country Snapshot of Diabetes Prevention and Control in the Americas; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/55326 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Vera-Montaño, A.; Santana-Mero, A.; Quimis-Cantos, Y. Prevalencia de Diabetes Mellitus Tipo 1 y Trastornos de la Conducta Alimentaria. Cienc. Salud 2021, 7, 1263–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J.; Loraine, L. Comportamiento clínico y enfoque terapéutico de los trastornos. Rev. Cuba. Med. Gen. Integral 2020, 36, e1280. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/mgi/v36n2/1561-3038-mgi-36-02-e1280.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Farnia, S.; Jahandideh, A.; Zamanfar, D.; Moosazadeh, M.; Hedayatizadeh-Omran, A. Prevalence of Eating Behaviors and Their Influence on Metabolic Control of Children with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Pediatr. Rev. 2023, 11, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racicka, E.; Bryńska, A. Eating Disorders in children and adolescents with Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes: Prevalence, risk factors, warning signs. Psychiatria 2015, 49, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Children and adolescents: Standards of medical care in diabetes. Care 2020, 43 (Suppl. S1), 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Torres, D. Alteraciones renales y electrolíticas en los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria: Una revisión sistemática. S. Am. Res. J. 2023, 3, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpot, U. Eating disorders in young people with diabetes. J. Diabetes Nurs. 2013, 17, 228–232. Available online: https://diabetesonthenet.com/wp-content/uploads/JDN17-6-228-32.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- De Paoli, T.; Rogers, P. Disordered eating and insulin restriction in type 1 diabetes: A systematic review and testable model. J. Treat. Prev. 2017, 26, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelvanayagam, S.; James, J. What is diabulimia and what are the implications for practice? Br. J. Nurs. 2018, 27, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candler, T.; Murphy, R.; Pigott, A.; Gregory, J. Fifteen-minute consultation: Diabulimia and disordered eating in childhood diabetes. Educ. Pract. Online First 2017, 3, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, A.; Khawaja, S.; Naguaib, M. Diabulimia: Current insights into type 1 diabetes and bulimia nervosa. Prog. Neurol. Psychiatry 2023, 27, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncone, A.; Cascella, C.; Chianese, A.; Zanfardino, A.; Piscopo, A.; Borriello, A.; Casaburo, F.; Del Giudice, E.M.; Iafusco, D. Body Image Problems and Disordered Eating Behaviors in Italian Adolescents With and Without Type 1 Diabetes: An Examination With a Gender-Specific Body Image Measure. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 556520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziewa, M.; Bańka, B.; Herbet, M.; Piatkowska-Chmiel, I. Eating Disorders and Diabetes: Facing the Dual Challenge. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncayo Pozo, D.; Alvarez, M. Diabulimia y redes sociales. Med. UTA 2024, 8, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Jimenez, M. Diabetes y trastornos de la conducta alimentaria. Nurs. Res. J. 2023, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dios, E.; Amuedo, S.; Venegas, E. Abordaje integral de los pacientes con trastornos de la conducta alimentaria y diabetes. Diabetes Trat. 2023, 1–4. Available online: https://www.revistadiabetes.org/wp-content/uploads/Abordaje-integral-de-los-pacientes-con-trastornos-de-la-conduct.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Moola, S.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, H.; Egata, G. Disordered eating behaviours and body shape dissatisfaction among adolescents with type 1 diabetes: A cross sectional study. J. Eat Disord. 2023, 11, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, C.; Smart, C.; Fatima, H.; King, B.; Lopez, P. Increased bolus overrides and lower time in range: Insights into disordered eating revealed by insulin pump metrics and continuous glucose monitor data in Australian adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2024, 18, 108904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J.; Madsen, J.; Jensen, A.; Olsen, B.; Johannesen, J. High prevalence of disordered eating behavior in Danish children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2020, 21, 1043–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, G. Eating disorders between male and female adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus in Korea. Belitung Nurs. J. 2022, 8, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, Ö.; Yılmaz, S.; Papatya, E. Frequency of Eating Disorders and Associated Factors in Type 1 Diabetic Adolescents. Med. J. Bakirkoy 2023, 2, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Propper-Lewinsohn, T.; Gillon-Keren, M.; Shalitin, S.; Elran-Barak, R.; Yackobovitch-Gavan, M.; Fayman, G.; David, M.; Liberman, A.; Phillip, M.; Oron, T. Disordered eating behaviours in adolescents with type 1 diabetes can be influenced by their weight at diagnosis and rapid weight gain subsequently. Res. Educ. Psychol. Asp. 2023, 40, e15166. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/dme.15166 (accessed on 20 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Şahin-Bodur, G.; Keser, A.; Siklar, Z.; Berberoğlu, M. Determining the risk of diabulimia and its relationship with diet quality and nutritional status of adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Nutr. Clin. Metab. 2020, 35, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, A.; Zahran, A.; Allam, A. The Impact of Air pollutants on oil industry and its relation to safety and occupational health. Int. J. Environ. Stud. Res. 2022, 1, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semalli, L.; Saracino, D.; Ber, I. Genetic forms of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: Current diagnostic approach and new directions in therapeutic strategies. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 176, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troncone, A.; Cascella, C.; Chianese, A.; di Leva, A.; Confetto, S.; Zanfardino, A.; Iafusco, D. Psychological support for adolescents with type 1 diabetes provided by adolescents with type 1 diabetes: The chat line experience. Pediatr. Diabetes 2019, 20, 800–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncone, A.; Chianese, A.; Cascella, C.; Zanfardino, A.; Piscopo, A.; Rollato, S.; Iafusco, D. Eating Problems in Youths with Type 1 Diabetes During and After Lockdown in Italy: An 8-Month Follow-Up Study. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2023, 30, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarcin, G.; Ozdemir, S.; Ata, A. Effect of Continuous Glucose Monitoring Device Assistance on Glycemic Control of 2023 Kahramanmaraş Doublet Earthquake Survivors with Type 1 Diabetes in Adana, Turkey. Turk. Arch. Pediatr. 2023, 58, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altabas, V.; Radošević, J.M.; Grubiješić, N. A Review on Diabulimia: Exploring the Intersection of Disordered Eating, Eating Disorders, Insulin Dose Manipulation, and Type 1 Diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleonora, P.; Carla, M.; Simona, F.; Angelica, S.; Umberto, F.; Brunella, I.; Tiziana, I.; Chiara, S.; Valentina, F.; Carlo, C.; et al. Disturbed eating behavior in pre-teen and teenage girls and boys with type 1 diabetes. Acta Biomed. 2018, 89, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project. Jamovi, Version 2.3.28. Computer software. The Jamovi Project: Sydney, Australia, 2022. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Ruppar, T. Meta-analysis: How to quantify and explain heterogeneity? Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2020, 19, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corraini, P.; Olsen, M.; Pedersen, L.; Dekkers, O.M.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. Effect modification, interaction and mediation: An overview of theoretical insights for clinical investigators. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 9, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).