Abstract

Background: The public harbors adverse perceptions of individuals with mental illness. The global prevalence of mental health illnesses has consistently risen. Untreated mental illness in high school adolescents can result in social, behavioral, and academic problems. Methods: A respondent-driven sample of 716 high school teachers working in Najran city was surveyed. The participants completed questionnaires assessing their mental health knowledge and Perceived Devaluation and Discrimination. Results: Almost two-thirds of participants had adequate knowledge. The highest knowledge scores were found in the items related to the effectiveness of medication and psychotherapy. Schizophrenia was the most recognized mental health condition, followed by bipolar disorder and depression (mean scores 4.3, 4.0, 3.9, respectively). Almost two-thirds of the study participants (73.6%) had high perceived stigma in the total score of the PDD scale. The highest scores of perceived stigma were found in the scale items related to hiring a qualified person with severe mental illness (86.3%) and being close friends with a person with severe mental illness (85.6%). Participants with adequate knowledge had more perceived social stigma than those with inadequate knowledge (77% versus 66%). There were statistically significant associations between Stigma-related mental health knowledge and socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants (p < 0.05). Conclusions: This study found that, despite the foundational level of knowledge, particularly regarding treatment effectiveness, gaps exist in understanding help-seeking behaviors. Socio-demographic factors play a role in shaping mental health literacy among high school teachers in Najran city.

1. Introduction

As reported by the WHO, almost fifty percent of all mental diseases manifest by mid-adolescence [1,2]. Untreated mental illness in secondary school adolescents can result in social, behavioral, and academic problems; exacerbation of symptoms or impairment; additional health comorbidities; suicidal tendencies; and the development of chronic diseases in adulthood [3,4].

The public harbors adverse perceptions of individuals with mental illness, including beliefs that they are hazardous, inept, erratic, feeble, and incapable of fulfilling assigned responsibilities. Consequently, individuals affected are estranged, marginalized, and ostracized from the broader community [5]. Students in secondary and tertiary education aged 15 to 24 exhibit comparable negative sentiments about individuals with mental illness as adults do [6,7].

Educational institutions are crucial in delivering teaching to pupils and fostering awareness regarding individuals with mental illness [8,9]. A contemporary obligation of educators is to assist and address students’ mental health needs. Educators can identify their students’ mental health issues and collaborate with school counselors, parents, and other mental health professionals [10]. They can address students’ inquiries, diminish the stigma around mental illness, and motivate students to seek assistance [11,12]. Consequently, examining instructors’ knowledge and attitudes regarding mental illness is crucial to guarantee that no deficiencies undermine these vital functions [13].

Mental health literacy is knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders that aid their recognition, management, or prevention. It goes beyond disease concepts to include skills for maintaining positive mental health and reducing stigma [14]. As initially stated by Jorm (1997) [14] and reiterated in later reviews, it encompasses understanding the features of mental illnesses and awareness of how to seek or provide help. Key components include the ability to recognize specific disorders, knowledge of risk factors/causes, familiarity with self-help and professional treatments, a positive attitude toward help-seeking, and knowing where to find reliable information [15].

Recent evidence positions teacher emotional competence and emotional self-efficacy as multidimensional, measurable constructs that shape inclusive practice through empirically verified pathways. Study by Calandri et al. (2025) concluded that teacher emotional competence (emotional intelligence, awareness, empathy, emotion regulation) is consistently associated with multiple indicators of inclusion (student engagement, socio-emotional development, classroom climate, teacher–student relations), recommending its integration in teacher education and policy [16].

While global estimates highlight the widespread impact of mental health conditions, the implications for educational professionals in Saudi Arabia remain underexamined. Understanding teachers’ mental health literacy is particularly relevant given their central role in early identification and student support. In the Saudi context, particularly in regions such as Najran, empirical data on teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and stigma toward mental illness are still limited.

This study aimed to assess the level of mental health literacy and the extent of perceived social stigma about mental disorders among high school teachers in Najran, Saudi Arabia.

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted from 1 September 2024 to 30 June 2025, in Najran, a city in southern Saudi Arabia. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board via Letter No. H-11-N-140 dated 29 June 2024, and written informed consent was obtained from all the participants in the study.

A complete sampling frame of high school teachers in Najran was not available; therefore, peer-to-peer invitations through teacher networks were feasible. We therefore used respondent-driven sampling (RDS) to approximate probability-based inference under standard RDS assumptions following STROBE-RDS (connected network; degree-informed recruitment; population-level without-replacement, motivating successive-sampling (SS) estimation) [17,18]. Recruitment began with 12 seeds purposively selected to balance gender, school type (public/private), and districts. Each participant received 3 coupons (max 3 recruits). Recruitment proceeded for 6 waves (max chain length = 6; median = 4). To minimize duplicate participation, each invited teacher received a unique survey link that could be used only once; the survey platform restricted multiple submissions from the same device by logging IP addresses and browser cookies.

Classroom teachers currently employed with direct student contact in the 2024–2025 academic year were included. Temporary/delegated teachers, administrative posts without classroom duties, and teachers not interacting with students were excluded.

The sample size was calculated using OpenEpi [19]. According to a previous study, the percentage of high school teachers with inadequate knowledge was 16.5% [6]. We assume that the total number of high school teachers in Najran city during the academic year 2023–2024 is 1150. At a two-sided α = 0.05, power (1 − β) = 0.80, and a 4.0 design effect, the sample size is 716 teachers.

The participants completed the questionnaires directly on Google Forms, which we then sent to the final database and downloaded as a Microsoft Excel sheet. We distributed the Google Form to the schools via WhatsApp (version 24.20.78) and Facebook (version 538). According to Google’s privacy policy, the participants’ answers were anonymous and confidential [20]. Participants had the option to withdraw from the survey at any point before submission; we did not save incomplete responses. The survey includes an introductory page describing the background, aims, as well as information on the survey’s ethics. The questionnaire consists of three parts:

The first part, a socio-demographic questionnaire, was used to collect participants’ primary socio-demographic data (including age, gender, level of education, and marital status) in addition to questions about the history of mental disorders and the history of any relations with patients with mental disorders.

The Mental Health Knowledge Schedule (MAKS) measures the second part, mental health literacy [15]. The MAKS comprises six items covering stigma-related mental health knowledge areas: help-seeking, recognition, support, employment, treatment, and recovery, and six items that inquire about the classification of various conditions as mental illnesses.

We score MAKS items on an ordinal scale (1 to 5). Items in which the respondent strongly agreed with a correct statement were valued at 5 points. In contrast, 1 point reflected a response in which the respondent strongly disagreed with an accurate statement. We calculate the total score for each participant by summing up the response values for each item. To determine the total score, we coded “Do not know” as neutral (3). Items 6, 8, and 12 were reverse-coded to reflect the direction of the correct response. Items 1–6 are used to determine the total score, ranging from 6 to 30.

The total score is calculated so that higher MAKS scores indicate better knowledge. The level of knowledge was considered adequate if the total score was above the median value [21]. Items 7 to 12 are designed to establish recognition and familiarity with various conditions and help contextualize the responses to other items [22].

The third part, the Perceived Devaluation and Discrimination Scale (PDD), is used to assess the degree of stigmatizing attitudes toward people with mental disorders [23]. It is designed to measure an individual’s perception of how most people view and treat others with mental illness. It does not assess the respondent’s attitudes and beliefs about societal stigma.

It contains 12 items, each rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (totally agree) to 5 (totally disagree). Items 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, and 10 required reverse scoring. Total scores ranged from 12 to 60, with higher scores indicating lower levels of perceived stigma. For each scale item, a low perceived stigma was defined as a score of 3 or higher. A perceived stigma score of 41 or above was considered low for the entire scale [24,25].

The reliability of the scales was tested through internal consistency measurement. They demonstrated an excellent level of reliability. For MAKS-knowledge, Cronbach’s α = 0.79, McDonald’s ω = 0.82 (95% CI 0.79–0.85). For PDD, Cronbach’s α = 0.86, McDonald’s ω = 0.88 (95% CI 0.86–0.90).

One month before the start of this study, a pilot study was conducted to demonstrate any data collection difficulties, evaluate the questionnaire’s validity and reliability, and estimate the time needed for data collection and expected frequency. No changes were made, so the pilot sample was included in the main sample.

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 was used to analyze the data collected [26]. The primary outcome variables were mental health knowledge and attitude. Major independent variables included socio-demographic variables of the study participants, teaching experience and specialty, history of mental disorders, and relationship with mental disorder patients. Qualitative variables were analyzed using Pearson’s chi-squared test. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Because teachers are nested within schools, we estimated intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for primary outcomes. Clustering by school was non-negligible. ICC for MAKS = 0.06 (95% CI 0.03–0.10; K = 48 schools; mean cluster size m = 15), giving DEFF ≈ 1 + (m − 1)·ICC = 1.84. ICC for PDD = 0.05 (95% CI 0.02–0.09). All models, therefore, used school-cluster–adjusted inference.

We analyzed the two scales, MAKS knowledge total and total PDD, using multiple linear regression (OLS) with RDS weights and RDS bootstrap standard errors to account for respondent-driven sampling recruitment trees. Binary predictors (e.g., sex, prior mental-health training, contact with a person with a mental disorder) were dummy-coded with stated reference categories; multi-category variables (e.g., education) were dummy-coded against Bachelor’s (reference). For each model, we report unstandardized coefficients (B), standardized coefficients (β), SE, t, exact p-values, 95% CIs, R2/Adjusted R2, VIF (multicollinearity), and Cohen’s f2 for effect size. Model assumptions (linearity, normality of residuals, homoscedasticity, independence) were checked; where minor deviations appeared, bootstrap inference was prioritized over transformations.

Multilevel sensitivity analyses were also run. We first calculated weighted estimates using the Volz–Heckathorn (VH, RDS-II) estimator, which assumes sampling with replacement and uses inverse network degree weighting. We then repeated the analyses using Gile’s successive sampling (SS) estimator, which accounts for sampling without replacement in finite populations. Key outcomes (e.g., adequate mental health knowledge and high perceived stigma) were compared across VH and SS estimators to assess the stability of the finding.

3. Results

Regarding the socio-demographic characteristics of the studied sample, 64.4% were under 40 years of age, 55.6% were females, and 54.2% were married. Almost half of the study participants had 10–20 years of experience, 68.0% had a bachelor’s degree, and 56.1% teach humanitarian subjects. Most of the study participants had not been diagnosed with a mental disorder, and 82.3% had not been in a relationship with mental disorders patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants.

The total score of the stigma-related mental health knowledge scale had a mean of 22.2 ± 3.1 and a median of 22. We classified participants into adequate and inadequate knowledge based on the median value. Almost two-thirds of participants had adequate knowledge. Regarding scale items, the highest knowledge scores were found in the third and fourth items, which related to the effectiveness of medication and psychotherapy, respectively (4.0 ± 0.8 for both). On the other hand, the lowest knowledge scores were found to be related to the sixth item, which states that most people with mental health problems go to a healthcare professional to obtain help (3.2 ± 1.1) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Stigma-related mental health knowledge among the study participants.

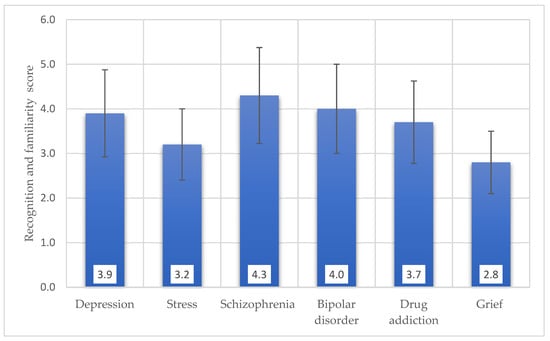

Regarding the recognition and familiarity with various mental health conditions, schizophrenia was the most recognized mental health condition, followed by bipolar disorder and depression (mean scores 4.3, 4.0, and 3.9, respectively) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Recognition and familiarity with various mental health conditions among the study participants.

Almost two-thirds of the study participants (73.6%) had high perceived stigma in the total score of the PDD scale. The highest scores of perceived stigma were found in the scale items related to hiring a qualified person with severe mental illness (86.3%) and being close friends with a person with severe mental illness (85.6%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Perceived Devaluation and Discrimination Scale (PDD) among the study participants.

There was a statistically significant association between stigma-related mental health knowledge and perceived social stigma in the study participants (p < 0.05). Participants with adequate knowledge had more perceived social stigma than those with inadequate knowledge (77% versus 66%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Association between Stigma-Related Mental Health Knowledge and Perceived Social Stigma in the Study Participants.

We compared our primary SS estimates with VH to assess robustness to RDS estimator choice, as recommended by STROBE-RDS reporting guidance (Table 4). Results were robust to the choice of RDS estimator. For inadequate knowledge, SS = 18.7% (95% CI 15.4–22.3) and VH = 19.4% (16.0–23.1); for mean PDD, SS = 44.2 (43.1–45.3) and VH = 44.0 (42.9–45.1). Point estimates and 95% CIs were nearly identical and overlapped throughout, indicating that conclusions do not depend on With- Vs. Without-Replacement assumptions; we therefore retain SS as primary and present VH as confirmatory.

Table 4.

RDS estimator sensitivity for key outcomes.

There were statistically significant associations between stigma-related mental health knowledge and socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants (p < 0.05). Participants below the age of 40 had significantly more adequate knowledge (75.3%) than older participants (60.8%). Male participants had more adequate knowledge (74.2%) than females (66.8%). Married participants had significantly less adequate knowledge (66.5%) than unmarried peers. In addition, master’s holders had significantly less adequate knowledge (60.3%) than bachelor’s holders (74.7%). Humanitarian subjects’ teachers had significantly more adequate knowledge (74.1%) than those who teach science subjects (65.0%). All participants who were previously diagnosed with a mental disorder had adequate knowledge. In addition, having a relationship with patients with mental disorders was associated with adequate knowledge (78.7%) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Association between stigma-related mental health knowledge and socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants.

Regarding the PDD scale, only two variables were associated with high perceived stigma: marital status and years of experience (p < 0.05). Unmarried participants had higher perceived stigma (77.3%) than their married peers (70.1%). High years of experience were associated with high perceived stigma, and participants with low experience had significantly lower perceived stigma (55.6%) than those with high expertise above 10 years (80.3% & 76.0%) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Association between Perceived Social Stigma and Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants.

RDS-weighted OLS models were used to examine predictors of mental health knowledge (MAKS) and perceived stigma (PDD) (Table 7). Teachers with prior mental-health training (β = 0.18, p < 0.001) and teaching experience years (β = 0.09, p = 0.003) were positively associated with high MAKS scores. The knowledge model explained 18.6% of the variance. For PDD, prior mental-health training (β = 0.16, p < 0.001), contact with a person with a mental disorder (β = 0.13, p < 0.001), and higher MAKS scores (β = 0.24, p < 0.001) were all associated with higher PDD scores, indicating lower perceived stigma. The stigma model explained 26.4% of the variance.

Table 7.

Regression predicting MAKS knowledge and PDD (RDS-weighted).

4. Discussion

The current study provides helpful information regarding mental health literacy and stigmatizing attitudes among Najran, Saudi Arabia, high school teachers. The study participants had a relatively strong understanding among teachers regarding the efficacy of conventional mental health treatments. This means that educators are increasingly exposed to information about mental health interventions. Conversely, the study identifies a gap in knowledge concerning help-seeking behaviors. While teachers may understand the effectiveness of treatments, they might underestimate the prevalence of professional help-seeking.

Similar studies on mental health literacy among educators often present various findings, with some studies reporting moderate to high levels of knowledge, while others identify significant gaps. For instance, a survey by Nalipay et al. (2023) emphasizes the importance of positive mental health literacy for teachers, noting that while knowledge of mental disorders is often explored, positive mental health aspects are less understood [27].

A Portuguese survey of 260 adolescents found that, on average, their literacy was only moderate; however, older female participants and those with healthier lifestyles scored higher [28].

A 2024 cross-sectional study of 1000 adolescents found “adequate literacy levels” in Spain. Still, it noted gaps in help-seeking (especially toward teachers), stigma against low-income individuals, and knowledge of severe conditions. Prior contact with mental illness was a key factor in better understanding and reducing stigma [29]. Similarly, global evidence reviews among children and youth in low- and middle-income countries report poor recognition and understanding of mental illness and pervasive stigma, with young people often favoring informal help (family, traditional healers) over professional care [30].

A recent Chinese survey found only 13.6% of urban and 8.6% of rural adults met an adequate MHL threshold. Key correlates were female sex, higher education, routines in urban samples, and younger age, marriage, and regular exercise in rural areas [31].

The recognition of specific mental health conditions also varies across studies. While schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression are often among the more recognized disorders, the order and level of recognition can differ based on cultural context, educational interventions, and exposure. Schizophrenia’s more obvious symptoms may make it easier to identify than other conditions.

Over time in Germany (1990–2020), recognition of schizophrenia rose from 18% to 34%, and recognition of major depression from 27% to 46%, reflecting modest gains in public MHL. Nonetheless, stigmatizing labels (e.g., “crazy”) persisted [32].

The high percentage of perceived stigma underscores a significant challenge in addressing mental health issues within the educational environment, indicating a potential area of concern that warrants targeted interventions. This deeply ingrained social stigma can manifest in attitudes toward personal and professional interactions with individuals experiencing severe mental illness. Studies often show that stigma can lead to reluctance in discussing mental health, seeking help, or interacting with individuals with mental health conditions.

For instance, research by Chaves et al. (2021) found that while teachers had some knowledge about obsessive–compulsive disorder, they also exhibited stigmatizing attitudes, albeit at low to moderate levels, in their specific sample [33]. In the current study, the high perceived stigma, particularly concerning hiring and close friendships, aligns with the broader understanding that social distance and discrimination are key components of mental health stigma. This suggests that even with some level of mental health literacy, personal biases and societal norms can contribute to significant stigmatizing attitudes.

There was a generational difference in mental health literacy, with younger teachers demonstrating higher levels of knowledge. Male participants had higher levels of expertise than females. This finding is notable, as some studies suggest varying levels of mental health literacy between genders, with women sometimes reporting higher levels of empathy and willingness to seek help, but not necessarily higher knowledge scores [34,35,36].

The current study found a significant association between marital status and mental health literacy. Marital status is not consistently identified as a strong predictor of mental health literacy in previous studies. Higher education levels are generally associated with greater knowledge. This could indicate a need for more targeted mental health education within master’s programs for educators. In addition, the nature of the subject taught might influence exposure to or interest in mental health-related topics.

Prabhu et al. (2021) found that teachers’ educational status, their marital status, teaching a class with an average strength of 31–60 students per class, previous mental health training, self-efficacy concerning seeking information on mental health, perceived ability to spread awareness, and ability to provide referrals were found to predict MHL among teachers [37].

Personal experience with mental illness, either directly or through close relationships, significantly enhances mental health literacy. This is a consistent finding across numerous studies. Direct or indirect contact with mental illness is widely recognized as a decisive factor in reducing stigma and increasing understanding [38,39,40].

More experienced teachers may hold higher levels of perceived stigma. This could be due to older generations having less exposure to mental health education or evolving societal attitudes toward mental illness. This aligns with the idea that older generations may have been raised in environments with less open discussion about mental health and more prevalent stigmatizing beliefs. This illustrates the value of ongoing professional development and mental health education for all educators, regardless of their years of experience.

Our findings only partially align with those reported in international samples of schoolteachers. Some studies have suggested that stigma toward mental illness decreases with longer teaching experience, whereas in our adjusted models, teaching experience was not significantly associated with PDD scores. This discrepancy may indicate that contextual or cultural factors in Saudi educational settings, including prevailing norms around mental illness and help-seeking, shape teacher perceptions differently. This highlights the need to design and evaluate context-specific mental health literacy interventions for teachers in Saudi Arabia.

There was a complicated interaction regarding marital status, knowledge, and stigma. Recent research has begun illuminating the complex pathways through which stigma operate, revealing that the relationship between knowledge and attitudes is not straightforward. While early anti-stigma efforts focused primarily on education and awareness campaigns based on the assumption that increased knowledge would lead to reduced stigma, empirical evidence suggests that multiple factors, including health literacy skills, cultural context, and individual characteristics, mediate this relationship [39,40,41].

5. Conclusions

The current study found that, despite the foundational level of knowledge, particularly regarding treatment effectiveness, gaps exist in understanding help-seeking behaviors. Perceived stigma is highly prevalent, especially regarding social and professional interactions with individuals who have severe mental illness, and this is a significant concern. Socio-demographic factors such as age, gender, marital status, education level, subjects taught, and personal experience all shape mental health literacy among high school teachers in Najran city.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.E. and A.S.; Data curation, H.A. (Hassan Alqureshah), N.A., S.A. and A.A.; Formal analysis, S.E.; Investigation, A.A.; Methodology, H.A. (Hesham Alrefaey); Project administration, S.E.; Resources, H.A. (Hassan Alqureshah), N.A., S.A. and A.A.; Supervision, S.E.; Validation, F.A.; Visualization, H.A. (Hidar Alqudhaya); Writing—original draft, H.A. (Hesham Alrefaey) and H.A. (Hidar Alqudhaya); Writing—review and editing, A.S. and F.A.; Visualization, S.A. and H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board Najran Health Cluster (Approval code: No. H-11-N-140, Approval date: 29 June 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MAKS | Mental Health Knowledge Schedule |

| PDD | Perceived Devaluation and Discrimination Scale |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| χ2 | Chi-Square Test |

References

- World Health Organization [WHO]. Adolescent Mental Health 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Mental Health Foundation. Mental Health Statistics: UK and Worldwide: Mental Health Foundation. 2022. Available online: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/explore-mental-health/statistics/children-young-people-statistics (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Sher, L. Individuals with untreated psychiatric disorders and suicide in the COVID-19 era. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2020, 43, 229–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.S. Student mental health: Some answers and more questions. J. Ment. Health 2018, 27, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, A.; Kostaki, E.; Kyriakopoulos, M. This systematic review examines the stigma of mental illness in children and adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 243, 469–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Omari, O.; Wynaden, D.; Alkhawaldeh, A.; Al-Delaimy, W.; Heslop, K.; Al Dameery, K.; Salameh, A.B. Knowledge and attitudes of young people toward mental illness: A cross-sectional study. Compr. Child. Adolesc. Nurs. 2020, 43, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlAzzam, M.; Abuhammad, S. Knowledge and attitude toward mental health and mental health problems among secondary school students in Jordan. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2021, 34, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, N.; Rahman, A.; Chaudhry, N.; Asif, A. World Health Organization “School Mental Health Manual”-based training for school teachers in urban Lahore, Pakistan: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2018, 19, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masumoto, Y.; Morinobu, S.; Fujimaki, K.; Kasagi, K. The observation dimensions of high school Yogo teachers play a crucial role in identifying prodromal symptoms of mental health issues in adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 5, 100173. [Google Scholar]

- Oban, G.; Küçük, L. Factors affecting stigmatization about mental disorders among adolescents. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2011, 2, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Stensen, K.; Lydersen, S.; Stenseng, F.; Wallander, J.L.; Drugli, M.B. Teacher nominations of preschool children at risk for mental health problems: How false is a false positive nomination and what make teachers concerned? J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2021, 43, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcluckie, A.; Kutcher, S.; Wei, Y.; Weaver, C. Sustained improvements in students’ mental health literacy with use of a mental health curriculum in Canadian schools. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadlaczky, G.; Hökby, S.; Mkrtchian, A.; Carli, V.; Wasserman, D. Mental Health First Aid is an efective public health intervention for improving knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour: A meta-analysis. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2014, 26, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorm, A.F. Mental health literacy: Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 177, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, F.; Gonçalves, P.; Sequeira, C. Mental health literacy: It is now time to put knowledge into practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 7030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calandri, E.; Mastrokoukou, S.; Marchisio, C.; Monchietto, A.; Graziano, F. Teacher Emotional Competence for Inclusive Education: A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gile, K.J.; Johnston, L.G.; Salganik, M.J. Diagnostics for respondent-driven sampling. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 2015, 178, 241–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.G.; Hakim, A.J.; Salganik, M.J.; Spiller, M.W.; Johnston, L.G.; Kerr, L.; Kendall, C.; Drake, A.; Wilson, D.; Orroth, K.; et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology for respondent-driven sampling studies:“STROBE-RDS” statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2015, 68, 1463–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, A.G.; Sullivan, K.M.; Soe, M.M. OpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Version 3.01; Emory University: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.openepi.com (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Google Privacy and Terms. Available online: https://policies.google.com/privacy?hl=en-US (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Ben Amor, M.; Zgueb, Y.; Bouguira, E.; Metsahel, A.; Aissa, A.; Thonicroft, G.; Ouali, U. Arabic validation of the “Mental Health Knowledge Schedule” and the “Reported and Intended Behavior Scale”. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1241611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans-Lacko, S.; Little, K.; Meltzer, H.; Rose, D.; Rhydderch, D.; Henderson, C.; Thornicroft, G. Development and psychometric properties of the Mental Health Knowledge Schedule. Can. J. Psychiatry 2010, 55, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattyn, E.; Verhaeghe, M.; Sercu, C.; Bracke, P. Public stigma and self-stigma: Differential association with attitudes toward formal and informal help seeking. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bifftu, B.B.; Dachew, B.A. Perceived Stigma and Associated Factors among People with Schizophrenia at Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A Cross—Sectional Institution Based Study. Psychiatry J. 2014, 2014, 694565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayan, A.; Jaradat, A. Stigma of Mental Illness and Attitudes toward Psychological Help-seeking in Jordanian University Students. Res. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2016, 4, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nalipay, M.J.; Chai, C.S.; Jong, M.S.; King, R.B.; Mordeno, I.G. Positive mental health literacy for teachers: Adaptation and construct validation. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 4888–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paakkari, L.; Torppa, M.; Mazur, J.; Boberova, Z.; Sudeck, G.; Kalman, M.; Paakkari, O. A comparative study on adolescents’ health literacy in Europe: Findings from the HBSC study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Sanguino, C.; Rodríguez-Medina, J.; Redondo-Pacheco, J.; Betegón, E.; Valdivieso-León, L.; Irurtia, M.J. An exploratory cross-sectional study on Mental health literacy of Spanish adolescents. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, L.; Pedley, R.; Johnson, I.; Bell, V.; Lovell, K.; Bee, P.; Brooks, H. Mental health literacy in children and adolescents in low-and middle-income countries: A mixed studies systematic review and narrative synthesis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 961–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.Y.; Tan, W.Y.; Guo, L.L.; Ji, Y.Y.; Jia, F.J.; Wang, S.B. Mental Health Literacy Among Urban and Rural Residents of Guangdong Province, China. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2024, 17, 2305–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grohmann, E.; Al-Addous, A.; Sander, C.; Dogan-Sander, E.; Baumann, E.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Schomerus, G. Changes in the ability to correctly identify schizophrenia and depression: Results from general population surveys in Germany over 30 years. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2024, 59, 1793–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, A.; Arnáez, S.; Roncero, M.; García-Soriano, G. Teachers’ knowledge and stigmatizing attitudes associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder: Effectiveness of a brief educational intervention. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 677567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Z.; Xie, J.; Liu, R.; Ou, L.; Lan, Z.; Xie, G. Gender-specific differences in mental health literacy and influencing factors among residents in Foshan City, China: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1555615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baklola, M.; Terra, M.; Taha, A.; Elnemr, M.; Yaseen, M.; Maher, A.; Buzaid, A.H.; Alenazi, R.; Osman Mohamed, S.A.; Abdelhady, D.; et al. Mental health literacy and help-seeking behaviour among Egyptian undergraduates: A cross-sectional national study. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, D.; Shafer, K. Gender and attitudes about mental health help seeking: Results from national data. Health Soc. Work 2016, 41, e20–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, V.; Ashok, L.; Kamath, V.G.; Sekaran, V.C.; Kamath, A.; Padickaparambil, S.; Hegde, A.P.; Devaramane, V. What predicts mental health literacy among school teachers? Ghana Med. J. 2021, 55, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullen, E.; Ekl, E.A.; Felix, E.; Turner, C.; Perry, B.L.; Pescosolido, B.A. Labeling, causal attributions, and social network ties to people with mental illness. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 293, 114646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Watson, A.C. Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry 2002, 1, 16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Gao, R.; Chen, H.; Yang, Z. Relationship between mental health literacy and professional psychological help-seeking attitudes in China: A chain mediation model. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Xia, J.; Chen, W.; Ye, J.; Xie, K.; Zhang, Z.; Binti Mohamad, S.M.; Shuid, A.N. Exploring the interplay of mental health knowledge, stigma, and social distance among clinical nurses: A study in Liaoning, China. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1478690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).