Abstract

Stickers, as an important nonverbal communication affordance on social media, have been understudied in Western contexts. This study employed an online survey (N = 300) to test two competing hypotheses—the social compensation and withdrawal hypotheses—to examine how personality traits influenced sticker use for emotional expression and self-presentation among U.S. college students. Results demonstrated that when communicating with a new friend on their mobile messenger, participants used stickers more frequently for self-presentation than emotional expression. Moreover, loneliness was positively related to neuroticism and negatively related to agreeableness and extraversion. Neuroticism was negatively related to sticker use for both emotional expression and self-presentation. However, neuroticism had a positive, indirect effect on both patterns of sticker use via loneliness. Furthermore, both a direct, positive relationship and an indirect, negative relationship emerged between extraversion and sticker use for emotional expression, with loneliness serving as the mediator. Theoretical and practical implications were also discussed.

1. Introduction

Virtual stickers (i.e., stickers) represent advanced versions of emojis that complement computer-mediated communication with nonverbal cues (Konrad et al., 2020). Compared to emojis, stickers feature animated designs and convey complicated emotional contexts, social situations, and social relationships, fulfilling more purposes than merely emotional expression (J. Y. Lee et al., 2016). However, due to different evolutionary stages of stickers across Eastern and Western cultures (Konrad et al., 2020), existing studies have mainly examined sticker uses in Eastern and cross-cultural contexts (e.g., S. Liu & Sun, 2020; Yang & Liu, 2024), while overlooking how and why stickers are used in Western countries.

The current study seeks to fill this void by examining the predictors of sticker use for both emotional expression and self-presentation among U.S. college students. The lexical hypothesis postulates that individuals’ daily language use can reflect their personality traits (Goldberg, 1981). As a graphical language, sticker choice for self-expression (i.e., emotional expression and self-presentation) resembles word choice in verbal communication, which is contingent on user personality (S. Liu & Sun, 2020).

Moreover, personality traits influence the extent to which individuals desire social connections (Erevik et al., 2023). When the need to belong is not satisfied by real-world relationships, loneliness arises (Heinrich & Gullone, 2006; Williams, 1983), which, in turn, affects how people interact with others in cyberspace. Accordingly, the current study tests two competing hypotheses regarding how loneliness among Americans with different personality traits (i.e., neuroticism, extraversion, and agreeableness) influences their sticker use for emotional expression and self-presentation in private chats. Specifically, the social compensation hypothesis (Reissmann & Lange, 2021) posits that lonely people try to develop meaningful relationships online to compensate for their real-life relationship deficits, whereas the social withdrawal hypothesis (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010) postulates that lonely people may not actively engage with others online for fear of rejection. Therefore, the current study contributes to the literature by examining the purposes of sticker use among U.S. college students and establishing loneliness as a mediator between personality traits and two purposes of sticker use.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Stickers as Nonverbal Cues on Social Media

Integral to most young people’s daily life (Faverio & Sidoti, 2024), social media has expanded its communicative affordances to improve the richness of online interaction and compensate for the lack of social presence. One such innovation is stickers, which have allowed users to more vividly express themselves. Compared to earlier versions of graphical icons such as emojis (Konrad et al., 2020), stickers may include both textual and pictorial information (Tang et al., 2021). Pictorial stickers embody oversized colored images that not only express senders’ emotions (Yang & Liu, 2024) but also their aesthetic preferences and personality traits (Derks et al., 2008). Unlike emojis that can be integrated into a sentence and posted on social networking sites, stickers are sent as stand-alone messages, mostly in private conversations (Tang et al., 2021).

Stickers can be either static or dynamic, featuring cartoon characters or real-life scenes that may display more body language than earlier graphical icons (Yang et al., 2023b). W. H. Lee and Lin (2020) have found that as stickers’ emotional expressions become more playful and dynamic, individuals are increasingly motivated to use stickers to enact their online identities. Therefore, stickers have gained greater popularity than GIFs (Susanto, 2018) on global instant messengers, such as Facebook Messenger, Skype, WeChat, Line, and KaKaoTalk (J. Y. Lee et al., 2016).

According to Bai et al.’s (2019) systematic review, existing research on emoji use has investigated the diversity of individuals—in terms of both demographics and psychographics—cultures, and platforms, the emotional and semantical functions of emojis in communication, and the inefficiency of emoji use due to expression ambiguities and diverse interpretations. Along similar lines, Tang and Hew (2019) have included emoticons and stickers—older and newer versions of emojis—in their review and identified two major themes of research: One revolves around the relationship orientation, which addresses the uses and implications of graphical icons in computer-mediated interpersonal relationships; the other focuses on the understanding orientation, which addresses the degree of mutual understanding of graphical icons (Tang & Hew, 2019). Because little quantitative research has examined the sociopsychological predictors of different types of sticker use, especially in Western contexts, where stickers have yet to reach peak popularity compared to East Asia (Konrad et al., 2020), the current study builds on existing literature and follows the line of relationship-oriented inquiry. Specifically, this study examines two major purposes of sticker use (Chang & Lee, 2016)—emotional expression and self-presentation—and investigates the individual psychological predictors of both patterns of sticker use during first online encounters among U.S. college students.

2.1.1. Emotional Expression

Communication online requires self-disclosure to reduce uncertainty and improve intimacy, and one major purpose of sticker use lies in emotional expression (Chang & Lee, 2016). Emotional expression has influenced social relationships, such that individuals who shared similar emotions were perceived as more likable and trustworthy (Qin et al., 2024). Stickers have been employed on social media to lighten up the mood in conversations (S. Liu & Sun, 2020). Even stickers featuring nonhuman faces but real or cartoon animals have widely served emotional functions (Jiang, 2021). Individuals who were more expressive and empathetic in face-to-face conversations found that using stickers featuring lively movements online represented how they would express emotions offline (Bae et al., 2024).

Stickers have been used to express both positive emotions (e.g., happiness, pride, gratitude) and negative emotions (e.g., sadness, anger, embarrassment, frustration) (Bae et al., 2024; Jiang, 2021; Tang et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2023a). Although social media generally features a positivity bias (i.e., refraining from expressing negative emotions) (Derks et al., 2008; Qin et al., 2024), stickers have enabled users to more playfully express their negative emotions without upsetting others (Bae et al., 2024). Moreover, close friends have created safe spaces for each other to express their negative emotions using stickers, through which friendship has developed over time (Chen, 2019).

2.1.2. Self-Presentation

The dramaturgical theory (Goffman, 1959) explains how an individual as a performer strategically presents themselves in front of an audience to manage impressions. Social media serves as a front stage where user performance—through textual and visual communication—has been viewed and assessed by the online audiences (Wang et al., 2019). As more individuals have developed visual literacy (Wang et al., 2019), employing stickers for self-presentation has become a new norm for Gen Z (Qiu et al., 2024), as textual communication alone might feel too distant (Qiu et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2019).

Specifically, the wide variety of characters with which users can identify (Jiang, 2021) has helped users build a personal brand (Chang & Lee, 2016; Qiu et al., 2024), present sociocultural differences (e.g., Derks et al., 2008), and highlight group membership (Qiu et al., 2024). As a result, young people have relied on stickers to present themselves as benevolent, other-focused, and straightforward (Marengo et al., 2017). Proficient sticker users have even constructed their desired image as creative, unique, fashionable, and tasteful (Wang et al., 2019). Given that existing research has not compared the frequencies of sticker use for different purposes in the U.S. context, the following research question is asked:

RQ1.

Will there be a significant difference between the frequencies of sticker use for emotional expression and self-presentation among U.S. college students?

2.2. Personality Traits and Sticker Use

Stylish stickers have been adopted to enhance users’ ability to more precisely express themselves while enhancing their online social prestige (W. H. Lee & Lin, 2020). However, social media users have demonstrated a moderate possibility of misconstruing the stickers sent to them (Tang et al., 2021). Therefore, the extent to which people would prefer this intentional ambiguity (Wang et al., 2019), tolerate potential misunderstanding (Yang & Liu, 2024), or favor the phatic component conveyed by stickers over their actual meanings (Tang et al., 2021) is likely dependent on their personality traits. Moreover, personality traits have been associated with online self-presentation (Michikyan et al., 2014), as individual personality differences have been encoded into the common phrases they use, which serves as the foundation for the Big-5 personality trait framework (Goldberg, 1981). Out of the five personality traits (i.e., neuroticism, agreeableness, extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness), Marengo et al. (2017) have found among English-speaking adults that 36 out of the 91 emojis examined in their research were significantly related to neuroticism, agreeableness, and extraversion. These three prominent traits have also demonstrated significant associations with loneliness among college students in Zhou et al.’s (2021) study. Therefore, the current study focuses on the influences of neuroticism, agreeableness, and extraversion on sticker use for emotional expression and self-presentation.

2.2.1. Neuroticism

Neuroticism features emotional instability (McCrae & John, 1992), which has been linked to sensitivity to threat, social insecurity, and anxiety (John & Srivastava, 1999). When it comes to emoji use, individuals who scored higher on neuroticism were more likely to adopt emojis that embody exaggerated facial expressions (Li et al., 2018) and identify with emojis conveying negative affect (e.g., anger, sadness, disappointment) (Marengo et al., 2017).

Additionally, expression online may bring risks of social rejection (Jackson, 2007), and using too many graphical icons may leave an impression of being superficial and immature (Wang et al., 2019). Therefore, highly neurotic users were less likely to use stickers in business settings (Chang & Lee, 2016) and group chats (S. Liu & Sun, 2020). On one hand, stickers have offered neurotic individuals a virtual vehicle to demonstrate their social skills that might not be apparent during in-person interactions. On the other hand, neurotics have been sensitive to negative social judgment and might struggle with finding the most appropriate stickers to use, thus heightening their social anxiety (Qiu et al., 2024). Given these conflicting concerns, the following research questions are proposed:

RQ2a–b.

Will neuroticism be significantly related to sticker use for (a) emotional expression and (b) self-presentation?

2.2.2. Agreeableness

Agreeableness represents cooperative and sympathetic behavior in interpersonal relationships (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Highly agreeable individuals care more about self-presentation during online interactions (Leary & Allen, 2011) and would like to project a positive self-image. As a result, they have adopted more heart-shaped emojis and positive emojis while seldom sending emojis that imply negative emotions and contentment (Li et al., 2018; Völkel et al., 2019). These patterns have communicated an intention to self-present as being other-focused, compliant, and benevolent (Li et al., 2018; Marengo et al., 2017). Furthermore, agreeableness has been positively associated with using stickers to express emotions, lighten up the mood, and present a sense of humor (S. Liu & Sun, 2020). Given agreeable people’s tendency to convey a positive self-image in cyberspace, it is postulated that:

H1a–b.

Agreeableness will be positively related to sticker use for (a) emotional expression and (b) self-presentation.

2.2.3. Extraversion

Characterized by being talkative, sociable, and outgoing (Costa & McCrae, 1985), extraversion has enabled individuals to use the Internet as a social extension for maintaining relationships (Tosun & Lajunen, 2010). As a result, this personality trait has prompted individuals to adopt more emojis that display positive sentiments (Marengo et al., 2017). Highly extraverted people have been more likely to use more stickers than their introverted counterparts both in general online communication and in business contexts (Chang & Lee, 2016), especially with elderly people or people in authority (S. Liu & Sun, 2020). Moreover, extraverts have also used more stickers to show their sense of humor and fewer stickers to avoid awkwardness (S. Liu & Sun, 2020). Because stickers can evoke a stronger motivation to connect with others (Yang et al., 2023b) and benefit extraverts’ networking, it is predicted that:

H2a–b.

Extraversion will be positively related to sticker use for (a) emotional expression and (b) self-presentation.

2.3. Loneliness, Personality Traits, and Social Media Use

As a key marker of social relationship deficits (Heinrich & Gullone, 2006), loneliness embodies a negative experience when an individual feels dissatisfied with their interpersonal relationships (Williams, 1983). Loneliness should be approached in relation to personality traits, as people’s degree of desired connectedness and priorities related to social relationships vary depending on their personality (Erevik et al., 2023). According to Buecker et al.’s (2020) meta-analysis, extraversion and agreeableness reduced loneliness, whereas neuroticism increased loneliness; the correlations between each personality trait and loneliness remained significant even when the other traits were controlled. The relationships between neuroticism, agreeableness, extraversion, and loneliness have been consistently observed by researchers in different cultural contexts (Erevik et al., 2023; Zhou et al., 2021). Based on this literature, it is hypothesized that:

H3a–c.

Loneliness will be positively predicted by (a) neuroticism, yet negatively predicted by (b) agreeableness and (c) extraversion.

In addition, loneliness has also been manifested in socialization challenges, such as difficulties in conducting self-introductions, showing kindness, and making friends, which has been linked to diminished self-disclosure (e.g., Heinrich & Gullone, 2006). This disengagement has reflected a social withdrawal tendency as a result of loneliness (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010). By contrast, the social compensation hypothesis (Reissmann & Lange, 2021) has predicted that lonely people who engage with more social web activities would increase their use of social media to build social bonds in order to fulfill their desire to be noticed. The current study thus examines these two competing hypotheses in the context of sticker use for emotional expression and self-presentation, in relation to loneliness.

2.3.1. Loneliness and Emotional Expression

From an evolutionary perspective (Spithoven et al., 2019), when the fundamental need to form close relationships is threatened by social exclusion or isolation, individuals have increased prosocial responses to address such relationship deficits (Faig et al., 2025). In line with the social compensation hypothesis (Reissmann & Lange, 2021), lonely individuals have exhibited an increased craving for social connection and belonging (Heinrich & Gullone, 2006), which has prompted them to actively seek emotional support to fulfill their belonging needs. Particularly, emotional expression (Keltner et al., 2019) has facilitated emotional intimacy and elicited emotional support. Harp and Neta (2023) have found that sharing positive emotions was effective in buffering against loneliness.

However, loneliness has presented a psychological paradox. By making individuals hypervigilant of social threats (e.g., relationship rejections), people might avoid social contact and suppress their emotions as a protective but maladaptive mechanism (Smith et al., 2019). That is, although loneliness triggers the desire for closeness, it also heightens fear of negative outcomes from social interactions. A recent meta-analysis by Patrichi et al. (2025) has identified a consistent, positive relationship between loneliness and emotional suppression, which suggests that lonely people might regulate their negative emotions by actively withdrawing from social interactions. Given this paradox, the following research question is proposed:

RQ3a.

Will loneliness be related to sticker use for emotional expression?

2.3.2. Loneliness and Self-Presentation

Similarly, the relationship between loneliness and self-presentation is also shaped by two primary mechanisms: a compensatory approach for relational deficit (Reissmann & Lange, 2021) and protective strategies to avoid social rejection (Jackson, 2007). From a compensatory perspective, the critical need for stable and supportive social relationships has motivated lonely individuals to engage in positive self-presentation to fulfill the desire to be noticed (Choi et al., 2018). Because digital platforms have afforded users greater control of visibility and impression management (Zhou et al., 2021), lonely young adults tend to construct idealized images on social media to gain social support and validation (Imran et al., 2023). However, overly fake self-presentation has created discrepancies between the real and projected self, which can further amplify loneliness (Borawski, 2021).

Conversely, protective self-presentation was adopted by lonely people to reduce social exposure and self-disclosure, as they feared disapproval and social incompetence (e.g., Jackson & Eglitis, 2005). Scott et al. (2018) observed that lonelier individuals commented or posted photos less actively, yet they engaged more passively on Facebook. Tian et al. (2019) revealed a similar association among college students between loneliness and protective self-presentation to avoid potential risks in social interactions.

The aforementioned competing theoretical arguments have led to mixed empirical findings on the relationship between loneliness and self-presentation. This inconsistency warrants further research to examine whether lonely individuals adopt stickers—a low-risk form of expression—for self-presentation. We thus propose the following research question:

RQ3b.

Will loneliness be significantly related to sticker use for self-presentation?

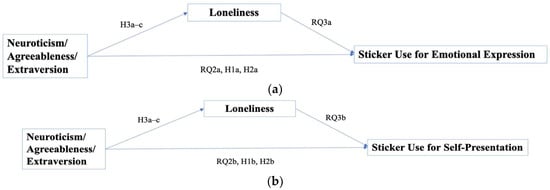

The conceptual models are presented in Figure 1a,b.

Figure 1.

The Conceptual Models. (a) Predictors of Sticker Use for Emotional Expression; (b) Predictors of Sticker Use for Self-Presentation.

3. Materials and Methods

After the study protocol received approval from the lead author’s institutional review board (X22-0207), data was collected through an online survey with a purposive sample, because stickers have been mainly used by young people (Chen, 2019). College students enrolled in a large Northeastern U.S. university were compensated with course credit for participating in the study. A total of 404 participants clicked into the survey, and 375 completed it.

A definition and a few examples of stickers were presented at the beginning of the survey to ensure a consistent understanding of items among participants. Specifically, participants were informed: “Stickers are a graphical expression for conveying emotional states, attitudes, and opinions on messaging applications for smartphones. Stickers are larger than emoticons [examples of emoticons are :) ;) ^_^] or emojis [examples of emojis are

], and stickers are typically fully illustrated characters and may include short text with the image. Stickers can be moving or static; they can feature cartoon characters, real-life scenes, or a combination of both real-life and cartoon elements [examples of stickers are

], and stickers are typically fully illustrated characters and may include short text with the image. Stickers can be moving or static; they can feature cartoon characters, real-life scenes, or a combination of both real-life and cartoon elements [examples of stickers are

].” Participants could proceed with the survey only after spending at least 10 s on the page and confirming their understanding of what stickers are. Then they assessed their familiarity with stickers and the frequency of sticker use in their daily mobile communication. After that, two prompts were presented to the participants for them to evaluate their likelihood of using stickers to express emotions and strategically present themselves when they had just added a new friend on their most frequently used mobile messenger. After completing all the scenario-specific questions, participants reported their personality traits, loneliness levels, and demographics using the following measures. Participants self-reported their primary country of residence and the number of years they had lived there; those who had not resided in the United States for most of their lives were excluded from data analysis. In measure selection, we prioritized pre-validated scales from existing literature while only creating new measures when necessary. Two attention check questions were adopted in the survey. To avoid the potential influence of later answers on earlier ones, participants could not go back throughout the survey. A complete list of survey items is available at https://osf.io/saq4h/overview?view_only=976de0fff8a8466bbbddfc920bc9a8b7 (accessed on 7 December 2025).

].” Participants could proceed with the survey only after spending at least 10 s on the page and confirming their understanding of what stickers are. Then they assessed their familiarity with stickers and the frequency of sticker use in their daily mobile communication. After that, two prompts were presented to the participants for them to evaluate their likelihood of using stickers to express emotions and strategically present themselves when they had just added a new friend on their most frequently used mobile messenger. After completing all the scenario-specific questions, participants reported their personality traits, loneliness levels, and demographics using the following measures. Participants self-reported their primary country of residence and the number of years they had lived there; those who had not resided in the United States for most of their lives were excluded from data analysis. In measure selection, we prioritized pre-validated scales from existing literature while only creating new measures when necessary. Two attention check questions were adopted in the survey. To avoid the potential influence of later answers on earlier ones, participants could not go back throughout the survey. A complete list of survey items is available at https://osf.io/saq4h/overview?view_only=976de0fff8a8466bbbddfc920bc9a8b7 (accessed on 7 December 2025).

], and stickers are typically fully illustrated characters and may include short text with the image. Stickers can be moving or static; they can feature cartoon characters, real-life scenes, or a combination of both real-life and cartoon elements [examples of stickers are

], and stickers are typically fully illustrated characters and may include short text with the image. Stickers can be moving or static; they can feature cartoon characters, real-life scenes, or a combination of both real-life and cartoon elements [examples of stickers are

].” Participants could proceed with the survey only after spending at least 10 s on the page and confirming their understanding of what stickers are. Then they assessed their familiarity with stickers and the frequency of sticker use in their daily mobile communication. After that, two prompts were presented to the participants for them to evaluate their likelihood of using stickers to express emotions and strategically present themselves when they had just added a new friend on their most frequently used mobile messenger. After completing all the scenario-specific questions, participants reported their personality traits, loneliness levels, and demographics using the following measures. Participants self-reported their primary country of residence and the number of years they had lived there; those who had not resided in the United States for most of their lives were excluded from data analysis. In measure selection, we prioritized pre-validated scales from existing literature while only creating new measures when necessary. Two attention check questions were adopted in the survey. To avoid the potential influence of later answers on earlier ones, participants could not go back throughout the survey. A complete list of survey items is available at https://osf.io/saq4h/overview?view_only=976de0fff8a8466bbbddfc920bc9a8b7 (accessed on 7 December 2025).

].” Participants could proceed with the survey only after spending at least 10 s on the page and confirming their understanding of what stickers are. Then they assessed their familiarity with stickers and the frequency of sticker use in their daily mobile communication. After that, two prompts were presented to the participants for them to evaluate their likelihood of using stickers to express emotions and strategically present themselves when they had just added a new friend on their most frequently used mobile messenger. After completing all the scenario-specific questions, participants reported their personality traits, loneliness levels, and demographics using the following measures. Participants self-reported their primary country of residence and the number of years they had lived there; those who had not resided in the United States for most of their lives were excluded from data analysis. In measure selection, we prioritized pre-validated scales from existing literature while only creating new measures when necessary. Two attention check questions were adopted in the survey. To avoid the potential influence of later answers on earlier ones, participants could not go back throughout the survey. A complete list of survey items is available at https://osf.io/saq4h/overview?view_only=976de0fff8a8466bbbddfc920bc9a8b7 (accessed on 7 December 2025).Measures

Sticker use for emotional expression. Respondents were asked to read the following prompt: “Think about the following scenario: When you just add a new friend on your most frequently used mobile messenger, during your first interaction, how likely is it for you to use stickers to express the following emotions?” The emotions included happiness, anger, sadness, surprise, fear, and disgust, based on Ekman et al.’s (1972) basic emotions (M = 1.73, SD = 0.79, α = 0.88). The prompt centered around communicating with a new friend, because online visual communication was contingent on the corresponding offline social hierarchy, and college students used more graphical icons only with their peers, compared to authority figures and family members (Wang et al., 2019). Stickers have also constituted a new communication style for young people to manage their friendships (Chen, 2019).

Sticker use for self-presentation. Respondents were also required to consider—during their first interaction with a friend just added on their most frequently used mobile messenger—how likely it was for them to use stickers to present their identity, personality, socially desirable traits, ideal self-image, aesthetic, and speech style (M = 1.97, SD = 1.03, α = 0.95).

Neuroticism/Extraversion/Agreeableness. Personality traits were measured with the scales developed by Rammstedt and John (2007). Specifically, respondents evaluated how well the following statements described their personality on a five-point Likert-type scale, including “I see myself as someone who is relaxed, handles stress well” and “I see myself as someone who gets nervous easily” (Neuroticism: M = 3.35, SD = 0.91). Two items, such as “I see myself as someone who is reserved” and “I see myself as someone who is outgoing, sociable” were used to measure extraversion (M = 3.03, SD = 1.02). Agreeableness was measured with the items that “I see myself as someone who is generally trusting” and “I see myself as someone who tends to find fault with others” (M = 3.51, SD = 0.81). Some items were reverse-coded.

Loneliness. The UCLA loneliness scale (Russell et al., 1978) was adopted. Respondents rated their level of agreement with the statements on a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = I never feel this way, 5 = I always feel this way). Example items included “I have nobody to talk to” and “I lack companionship” (M = 2.13, SD = 0.83, α = 0.96).

Control variables. Information on respondent gender (Nmen = 124, Nwomen = 168, Nnon-binary = 6), age (M = 19.16, SD = 0.93), and sticker familiarity (M = 4.12, SD = 0.94) was also collected.

4. Results

Responses that failed the attention check questions were excluded. After data cleaning, 300 out of 375 completed responses from U.S. college students were retained for analysis. Respondents averaged 19.16 years old (SD = 0.93), with 211 (70.3%) self-identified as White, 36 (12.0%) as Hispanic or Latino, 25 (8.3%) as Black or African American, 50 (16.7%) as Asian, 1 (0.3%) as Pacific Islander, and 7 (2.3%) as other. In terms of gender composition, 168 (56.0%) women, 124 (41.3%) men, and 6 (2.0%) non-binary identifying students were included in the sample. A majority of respondents (N = 174, 58.0%) selected their phone texting applications as their most frequently used mobile messenger, and 99 (33.0%) used Snapchat most frequently. WeChat (N = 8, 2.7%), WhatsApp (N = 6, 2.0%), Instagram (N = 4, 1.4%), Discord (N = 3, 1.0%), Skype (N = 2, 0.7%), Line (N = 1, 0.3%), QQ (N = 1, 0.3%), and Telegram (N = 1, 0.3%) were also used. On average, respondents were familiar with stickers (M = 4.12, SD = 0.94) and sometimes (M = 2.89, SD = 1.23) used stickers in their daily mobile communication.

Zero-order correlations and descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. Collinearity diagnostics suggested that the variance inflation factor (VIF) values were all under 1.33, so collinearity was nominal.

Table 1.

Means Standard Deviations and Correlations.

In order to test whether there is a significant difference between the frequencies of sticker use for emotional expression and self-presentation (RQ1), a paired-samples t-test was conducted. Results showed that sticker use for self-presentation (M = 1.97, SD = 1.03) was significantly higher than sticker use for emotional expression (M = 1.73, SD = 0.79), t (298) = 6.18, p < 0.001. Cohen’s d = 0.36 (95% CI [0.24, 0.47]), which indicates a small-to-medium effect size. With a sample size of 300, the Shapiro-Wilk test indicated that the assumption of normality was not strictly met, W (299) = 0.86, p < 0.001. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was also conducted, which further confirmed that more respondents reported higher frequencies of sticker use for self-presentation than emotional expression, Z = −6.15, p < 0.001.

4.1. Model 1: Sticker Use for Emotional Expression as Dependent Variable

Because sticker use for emotional expression and self-presentation were considered different outcome variables in the present study, parallel models (see Figure 1a,b) were run separately to test all remaining hypotheses and research questions. Research model 1 (Figure 1a) was tested using Model 4 of Hayes’s (2017) PROCESS procedure 4.0, with loneliness and sticker use for emotional expression serving as the mediator and dependent variable (DV). Neuroticism, agreeableness, and extraversion were entered into each sub-model as independent variables (IVs), respectively. Familiarity with stickers, age, and gender served as covariates.

4.1.1. Neuroticism as IV

When neuroticism was entered as the IV, the entire regression model was statistically significant, F (5, 293) = 6.04, R2 = 0.09, p < 0.001. H3a hypothesized that neuroticism would be positively related to loneliness, which was supported (b = 0.31, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001). RQ3a examined the relationship between loneliness and sticker use for emotional expression. Results suggested a positive relationship between these two variables (b = 0.15, SE = 0.06, p = 0.008). RQ2a investigated the relationship between neuroticism and sticker use for emotional expression, and results showed a negative direct relationship (b = −0.18, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001).

The indirect effect of neuroticism on sticker use for emotional expression—using bootstrapping estimation with 5000 bootstrap samples and 95% confidence intervals (CIs)—was also tested, with loneliness being the mediator, as illustrated in Figure 1a. Results demonstrated that neuroticism indirectly predicted more sticker use for emotional expression via loneliness (b = 0.05, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.01, 0.08]). Thus, the total effect of neuroticism on sticker use for emotional expression was still negative (b = −0.13, SE = 0.05, p = 0.010, 95% CI [−0.23, −0.03]).

4.1.2. Agreeableness as IV

With agreeableness being the IV and all other variables remaining the same, the entire regression model was statistically significant, F (5, 291) = 3.83, R2 = 0.06, p = 0.002. H3b posited that agreeableness would be negatively related to loneliness, which was confirmed (b = −0.25, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001). H1a hypothesized that agreeableness would be positively related to sticker use for emotional expression, which was not supported (b = 0.06, SE = 0.06, p = 0.300). RQ3a explored whether loneliness would be significantly related to sticker use for emotional expression. The relationship emerged as not significant (b = 0.11, SE = 0.06, p = 0.055). No indirect effect between agreeableness and sticker use for emotional expression (b = −0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.07, 0.003]) was found, either.

4.1.3. Extraversion as IV

When extraversion served as the IV of the model, the entire regression model was statistically significant, F (5, 293) = 5.20, R2 = 0.07, p < 0.001. H3c hypothesized that extraversion would be negatively related to loneliness, which was supported (b = −0.33, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001). H2a postulated that there would be a positive relationship between extraversion and sticker use for emotional expression, which was validated (b = 0.10, SE = 0.05, p = 0.034). RQ3a tested the association between loneliness and sticker use for emotional expression. Results also revealed a positive relationship (b = 0.14, SE = 0.06, p = 0.019). Furthermore, a significant indirect effect of extraversion on sticker use for emotional expression was identified (b = −0.05, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.09, −0.003]).

4.2. Model 2: Sticker Use for Self-Presentation as DV

Model 2 replaced sticker use for emotional expression with sticker use for self-presentation as the DV, and all other variables were entered in the same way as they were in Model 1 (see Figure 1b). Hypothesis testing results for H3a, H3b, and H3c remained the same, indicating that neuroticism was positively related to loneliness, whereas extraversion and agreeableness were negatively related to loneliness.

4.2.1. Neuroticism as IV

When neuroticism was entered into Model 2 as the IV, the entire regression model was still significant, F (5, 292) = 6.29, R2 = 0.10, p < 0.001. RQ3b tested the relationship between loneliness and sticker use for self-presentation. Results suggested a positive relationship (b = 0.16, SE = 0.07, p = 0.028). RQ2b inquired into the relationship between neuroticism and sticker use for self-presentation, and results indicated a negative direct relationship between them (b = −0.20, SE = 0.07, p = 0.005).

The indirect effect of neuroticism on sticker use for self-presentation was further tested, with loneliness being the mediator (see Figure 1b). Results demonstrated that neuroticism was indirectly related to more sticker use for self-presentation via loneliness (b = 0.05, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.01, 0.09]). Accordingly, the total effect of neuroticism on sticker use for self-presentation was still negative (b = −0.15, SE = 0.07, p = 0.026, 95% CI [−0.28, −0.02]).

4.2.2. Agreeableness as IV

With agreeableness being the IV for Model 2, the entire regression model remained statistically significant, F (5, 291) = 5.10, R2 = 0.08, p < 0.001. H1b predicted that agreeableness would be positively related to sticker use for self-presentation, which was not supported (b = 0.12, SE = 0.07, p = 0.095). RQ3b investigated whether loneliness would be significantly related to sticker use for self-presentation. The relationship was not significant (b = 0.13, SE = 0.07, p = 0.074). No indirect effect existed between agreeableness and sticker use for self-presentation (b = −0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.08, 0.005]), either.

4.2.3. Extraversion as IV

When extraversion served as the IV for Model 2, the entire regression model was significant, F (5, 292) = 5.25, R2 = 0.08, p < 0.001. H2b postulated that there would be a positive relationship between extraversion and sticker use for self-presentation, which was disconfirmed (b = 0.11, SE = 0.06, p = 0.072). RQ3b tested the relationship between loneliness and sticker use for self-presentation. Results did not support this relationship (b = 0.15, SE = 0.08, p = 0.052). Moreover, no indirect effect of extraversion on sticker use for self-presentation was identified (b = −0.05, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [−0.11, 0.001]). Results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of Analyses.

5. Discussion

The current research represents one of the first quantitative studies that explore the predictors of sticker use for both emotional expression and self-presentation among college students in a lower-context, Western culture. Thus, we extend visual venues for online self-presentation from selfies (e.g., Yang et al., 2021) to stickers. Moreover, by demonstrating that U.S. college students’ sticker use was driven by both dispositional and psychological factors, this study provides support to the social compensation hypothesis (Reissmann & Lange, 2021) among highly neurotic and extraverted social media users.

First, in response to RQ1, results showed that stickers were more frequently used for self-presentation than emotional expression by American college students when they interacted with a new friend. This empirical finding also aligns with W. H. Lee and Lin’s (2020) observation in the Korean context that as sticker design became much more complicated—featuring playfulness and uniqueness—self-expression and conspicuousness have emerged as more important motivations for sticker adoption than other purposes. Thus, as graphical icons evolve in design and presentation modality, the unique mechanisms driving their adoption should be examined.

To answer RQ2a and RQ2b, neuroticism was negatively related to sticker use for both emotional expression and self-presentation. This indicates that highly neurotic individuals reduced sticker use, probably for fear of potential social rejections due to inappropriate sticker choices (Qiu et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2019). Because the body language and dynamic nature of stickers (Yang et al., 2023b) render them more emotionally expressive than emojis and emoticons, highly neurotic social media users might refrain from sticker use to show their emotional stability, engaging in false self-presentation (Michikyan et al., 2014).

Moreover, extraversion was positively related to sticker use for emotional expression—supporting H2a—but not related to sticker use for self-presentation, which disconfirmed H2b. Li et al. (2018) found that X users who scored lower on extraversion used emojis most frequently, whereas Völkel et al. (2019) did not identify a significant relationship between extraversion and total emoji use. Our study reconciled these seemingly contradictory findings by differentiating graphical icon use. Specifically, because extraverts were less sensitive to interpersonal conflicts and negative social judgment, they might express their emotions more spontaneously, without much reliance on emojis in online discussions for strategic self-presentation (Yang et al., 2025).

Contrary to H1a and H1b, agreeableness was not significantly related to either type of sticker use. In line with these seemingly surprising findings, Yang et al. (2023b) have noted that allocentrism—a collectivistic personality attribute closely related to agreeableness (Czerniawska & Szydło, 2021)—did not increase sticker use. One potential reason might lie in the emotional intensity and expressiveness of stickers, which could be considered by highly agreeable people as being too direct or dramatic and thus inappropriate for first online encounters.

Furthermore, in line with our hypotheses H3a, H3b, and H3c, highly extraverted and agreeable individuals were less likely to feel lonely, whereas neurotics were more likely to experience loneliness. As personality embodies an individual’s stable cognitive, emotional, and behavioral patterns, such as a preference for social engagement and interpersonal behavior, personality traits have been well-explained as individual differences in loneliness (Buecker et al., 2020). However, loneliness complicated the relationships between personality traits and sticker use, which is elaborated below.

Specifically, loneliness increased sticker use for both emotional expression and self-presentation among neurotics (i.e., RQ3a and RQ3b), suggesting a tendency to seek social compensation on social media (Reissmann & Lange, 2021). However, a suppression effect emerged when loneliness served as a mediator between neuroticism and two types of sticker use, such that despite negative, direct relationships between neuroticism and sticker use, neuroticism indirectly predicted more sticker use via loneliness. This finding has practical implications, as an increase in sticker use among neurotic individuals may signal underlying loneliness, suggesting a potential need for social or even clinical support. Thus, sticker use proved to be a function of both personality traits and emotional states.

Moreover, loneliness also prompted sticker use for emotional expression—rather than self-presentation—among extraverts (i.e., RQ3a and RQ3b). By contrast, extraversion imposed an indirect, negative effect on sticker use for emotional expression via loneliness. This finding suggests that although loneliness boosted sticker use, extraverted individuals were less likely to feel lonely (Erevik et al., 2023), thus reducing sticker use through this pathway. Even though extraversion could directly increase sticker use for emotional expression, if extraverts suddenly use more stickers to express emotions than usual, this behavioral change may reflect their heightened loneliness in the real world and desire for social compensation through online communication. Taken together, loneliness changed the role of stickers in digital communication, as most graphical icons are considered positive, and sharing positive emotions can buffer loneliness-related negativity (Harp & Neta, 2023).

Additionally, regarding RQ3a and RQ3b among highly agreeable people, loneliness was not associated with either type of sticker use. As agreeable individuals have typically been more accommodating (Priyadarshini, 2017), they may prioritize others’ comfort over their own ease of emotional expression and self-presentation even when they feel lonely, thus refraining from using stickers, which may be perceived as flaunting (W. H. Lee & Lin, 2020). Thus, this finding has extended the current social compensation hypothesis by highlighting that strategic self-presentation and emotional expressions are not equally applicable across personality traits.

Notably, the mean values of sticker use for both emotional expression and self-presentation remained low. On one hand, our research has provided new quantitative evidence to the previous finding that stickers have been used in more intimate relationships among English-speaking social media users, compared to Asians (Konrad et al., 2020). American young people might generally prefer to start with basic emoticons and emojis to project a positive impression while avoiding being perceived as frivolous, until the relationship has become stable (Wang et al., 2019). However, on the other hand, Labato and Yang (2021) have found that although American college students used fewer stickers than their Chinese counterparts before the COVID-19 pandemic, their sticker use frequencies converged during the pandemic, showing no significant differences. Because sticker use is a function of cultural, technological, situational, and individual factors (Yang et al., 2023a), researchers should further investigate whether American young people have returned to their originally lower sticker use frequency since the end of the pandemic, or they have just differentiated sticker use depending on the nature of social interactions. This investigation will help answer the question raised by Konrad et al. (2020), which is whether stickers will displace emojis as they have done in Asia or remain secondary emojis on Western social media platforms. Moreover, our research findings carry profound implications for intercultural communication, as not only the emotions expressed by stickers (Yang & Liu, 2024) but also the frequency of sticker use with new friends may also differ between new friends from Eastern and Western countries. Because computer-mediated communication is likely to be hyperpersonal (Walther, 1996), further academic attention should be directed towards how American young people disclose about themselves on social media, in order not to make their new Asian friends feel distant.

On balance, our findings have demonstrated that sticker use for emotional expression and self-presentation in digital communication was predicted by both proximal and distal factors, which fall within the broader theoretical framework of the interactive communication technology adoption model (ICTAM) (Lin, 2003). According to Lin (2003), ICTAM drew from uses and gratifications theory (Katz et al., 1973) and considered both personality traits and user expectancy as potential predictors of technology adoption, in specific social, cultural, and political contexts. By empirically documenting how emotional expression and self-presentation were manifested in the Western digital context and how loneliness—as a result of personality traits—changes the role of stickers in communication, the current study has contributed to the ever-evolving area of computer-mediated communication technology adoption and uses, from a de-westernized perspective.

The current study has several limitations, which should be addressed by future researchers. First, a cross-sectional survey with 300 valid responses from one Northeastern U.S. university may not be generalizable. Demographics, such as gender, racial, and age compositions, as well as intercultural communication competence (Yang et al., 2023b), may influence U.S. students’ sticker use patterns. More participants and universities should be studied in future research to obtain results that illustrate the trends discovered in the current study. Second, self-report measures were adopted to assess participants’ perceived likelihood of using stickers in hypothetical scenarios, which might not accurately reflect their actual behavior, especially in dynamic social interactions where users may either misevaluate the influence of the situation (Hayes, 2007) or the intensity of their emotions (Yang et al., 2025). Specifically, Bae et al. (2024) and Chen (2019) have adopted either a diary or participatory observation in their qualitative studies to collect data. Future quantitative research could also consider using behavioral trace data or diary studies to improve ecological validity. Third, emotional expression and self-presentation were conceptualized as different types of sticker use in two parallel models. However, as indicated by their strong correlation (see Table 1), emotional expression represents an important aspect of online self-presentation that influences impression formation (Qin et al., 2024). Accordingly, later such research should explore the predictors of these two types of sticker use in integrated models. Moreover, the UCLA loneliness scale did not differentiate between social and emotional loneliness (Heinrich & Gullone, 2006). Neither did the current study differentiate between real, ideal, and fake self-presentation (Michikyan et al., 2014). Future researchers should operationalize these constructs as multi-dimensional variables and explore more nuanced connections between them. Fourth, the relationship between agreeableness and sticker use has been understudied in existing literature, and the present research failed to sufficiently explain how agreeableness influenced sticker use. Thus, future studies should examine whether sticker design or the level of relational closeness has discouraged agreeable people from using stickers for emotional expression and self-presentation on social media during first encounters. Fifth, platform differences can influence user perceptions and adoption of stickers (Yang et al., 2023b), which should be controlled. Lastly, individual intentions to align with or break away from gender stereotypes with sticker use (Chen, 2019) may vary depending on the gender of their message recipient; later work should control for the gender of the newly added social media contact in the hypothetical scenario presented to respondents in the survey.

6. Conclusions

The current research features a scientific investigation of the social and cultural dimensions of social media, with a special interest in the latest technological affordances (i.e., virtual stickers) provided on international social media platforms that aim to facilitate nonverbal communication and emotional support seeking online. This quantitative study has extended past work conducted mainly in East Asian societies on stickers to the traditionally understudied Western contexts, by examining the predictors of two purposes of sticker use among American college students. The fact that stickers are more frequently used for self-presentation than emotional expression when users are interacting with a friend newly added as their contact highlights American college students’ stronger intention to manage impressions than express emotions by employing social media affordances. Loneliness inconsistently mediates the relationships between neuroticism and both types of sticker use, alongside the relationship between extraversion and sticker use for emotional expression, which lends credence to the social compensation hypothesis. Study findings replicate previous research on the associations between neuroticism, extraversion, and agreeableness and loneliness, while calling for further exploration on the relationship between agreeableness and sticker use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Y.; methodology, D.Y.; formal analysis, D.Y.; resources, D.Y.; data curation, D.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Y. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, D.Y., Y.L. and M.N.; visualization, D.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Connecticut (protocol code X22-0207 and date of approval 28 September 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The study dataset can be downloaded at: https://osf.io/vq7jk/overview?view_only=7093bb40139e45b790523b92959beace (accessed on 7 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bae, G., Kwak, D., & Lim, Y. K. (2024). Why I choose this sticker when chatting with you: Exploring design considerations for sticker recommendation services in mobile instant messengers. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 8(CSCW2), 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Q., Dan, Q., Mu, Z., & Yang, M. (2019). A systematic review of emoji: Current research and future perspectives. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borawski, D. (2021). Authenticity and rumination mediate the relationship between loneliness and well-being. Current Psychology, 40, 4663–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buecker, S., Maes, M., Denissen, J. J. A., & Luhmann, M. (2020). Loneliness and the Big Five personality traits: A meta–analysis. European Journal of Personality, 34(1), 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y. C., & Lee, J. (2016). The impact of social context and personality toward the usage of stickers in LINE. In G. Meiselwitz (Ed.), Social computing and social media. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 9742. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-P. (2019). Friendships through the style choice of virtual stickers: Young adults manage aesthetic identity and emotion on a social messaging line app. International Journal of Market Research, 63(2), 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.-W., Chun, S.-Y., Lee, S. A., Han, K.-T., & Park, E.-C. (2018). The association between parental depression and adolescent’s Internet addiction in South Korea. Annals General Psychiatry, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1985). The NEO personality inventory manual. Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). NEO PI-R professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Czerniawska, M., & Szydło, J. (2021). Do Values relate to personality traits and if so, in what way? Analysis of relationships. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 14, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derks, D., Bos, A. E. R., & Von Grumbkow, J. (2008). Emoticons in computer-mediated communication: Social motives and social context. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 11(1), 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V., & Ellsworth, P. (1972). Emotion in the human face: Guidelines for research and an integration of findings. Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erevik, E. K., Vedaa, Ø., Pallesen, S., Hysing, M., & Sivertsen, B. (2023). The five-factor model’s personality traits and social and emotional loneliness: Two large-scale studies among Norwegian students. Personality and Individual Differences, 207, 112115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faig, K. E., Henoch, A. C., Mousa, M. S., & Smith, K. E. (2025). How does loneliness impact emotion perception? A systematic review. Current Research in Behavioral Sciences, 9, 100181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faverio, M., & Sidoti, O. (2024, December 12). Teens, social media and technology 2024. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2024/12/12/teens-social-media-and-technology-2024/ (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, L. R. (1981). Language and individual differences: The search for universals in personality lexicons. Review of Personality and Social Psychology, 2(1), 141–165. [Google Scholar]

- Harp, N. R., & Neta, M. (2023). Tendency to share positive emotions buffers loneliness-related negativity in the context of shared adversity. Journal of Research in Personality, 102, 104333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2007). Exploring the forms of self-censorship: On the spiral of silence and the use of opinion expression avoidance strategies. Journal of Communication, 57(4), 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, L. M., & Gullone, E. (2006). The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(6), 695–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, H., Khanum, S., & Shahzadi, M. (2023). The relationship of loneliness, self-motives, and selfie-posting behavior among selfie lovers. Annals of Human and Social Sciences, 4(3), 482–491. Available online: https://ojs.ahss.org.pk/journal/article/view/488 (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Jackson, T. (2007). Protective self-presentation, sources of socialization, and loneliness among Australian adolescents and young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(6), 1552–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T., & Eglitis, K. (2005). “My name’s Jasper and I’m a Sagittarius”: Threat, social anxiety, and the impact on making a personal introduction videotape. Journal of Worry and Affective Experience, 1(3), 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X. (2021). Perceptual attributes of human-like animal stickers as nonverbal cues encoding social expressions in virtual communication. In X. Jiang (Ed.), Types of nonverbal communication (pp. 1–19). IntechOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin, & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 102–138). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1973). Uses and gratifications research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 37(4), 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, D., Sauter, D., Tracy, J., & Cowen, A. (2019). Emotional expression: Advances in basic emotion theory. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 43, 133–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, A., Herring, S. C., & Choi, D. (2020). Sticker and emoji use in Facebook messenger: Implications for graphicon change. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 25(3), 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labato, L., & Yang, D. (2021). I see how you feel: How virtual stickers connect us emotionally across distance and culture. The Chronicle of Mentoring & Coaching, 5(14), 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, M. R., & Allen, A. B. (2011). Self-presentational persona: Simultaneous management of multiple impressions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(5), 1033–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Y., Hong, N., Kim, S., Oh, J., & Lee, J. (2016). Smiley face: Why we use emoticon stickers in mobile messaging. In Proceedings of the 18th international conference on human-computer interaction with mobile devices and services adjunct (pp. 760–766). ACM. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W. H., & Lin, Y. H. (2020). Online communication of visual information: Stickers’ functions of self-expression and conspicuousness. Online Information Review, 44(1), 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W., Chen, Y., Hu, T., & Luo, J. (2018, June 25–28). Mining the relationship between emoji usage patterns and personality. Proceedings of the Twelfth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2018), Palo Alto, CA, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. A. (2003). An interactive communication technology adoption model. Communication Theory, 13(4), 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., & Sun, R. (2020). To express or to end? Personality traits are associated with the reasons and patterns for using emojis and stickers. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, D., Giannotta, F., & Settanni, M. (2017). Assessing personality using emoji: An exploratory study. Personality and Individual Differences, 112, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R. R., & John, O. P. (1992). An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. Journal of Personality, 60(2), 175–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michikyan, M., Subrahmanyam, K., & Dennis, J. (2014). Can you tell who I am? Neuroticism, extraversion, and online self-presentation among young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrichi, A., Rimbu, R., Miu, A. C., & Szentágotai-Tǎtar, A. (2025). Loneliness and emotion regulation: A meta-analytic review. Emotion, 25(3), 755–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, S. (2017). Effect of personality on conflict resolution styles. IRA-International Journal of Management & Social Sciences, 7(2), 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Qin, Y., Cho, H., Yang, D., & Li, P. (2024). Emotional expressions and first impression formation in social media profiles. Media Psychology, 28(4), 548–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H., Goh, D. H.-L., Liu, R., & Schulz, P. J. (2024). From stickers to personas: Utilizing instant messaging stickers for impression management by Gen Z. iConference 2024. In Wisdom, well-being, win-win. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 14597. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammstedt, B., & John, O. P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the big five inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reissmann, A., & Lange, K. W. (2021). The role of loneliness in university students’ pathological Internet use—A web survey study on the moderating effect of social web application use. Current Psychology, 42, 11834–11848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Ferguson, M. L. (1978). Developing a measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 42(3), 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G. G., Boyle, E. A., Czerniawska, K., & Courtney, A. (2018). Posting photos on Facebook: The impact of narcissism, social anxiety, loneliness, and shyness. Personality and Individual Differences, 133, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. V., Lair, E. C., & O’Brien, S. M. (2019). Purposely stoic, accidentally alone? Self-monitoring moderates the relationship between emotion suppression and loneliness. Personality and Individual Differences, 149, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spithoven, A. W. M., Cacioppo, S., Goossens, L., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2019). Genetic contributions to loneliness and their relevance to the evolutionary theory of loneliness. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 376–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susanto, B. S. (2018, July 31). The evolution of communication and why stickers matter. Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2018/07/31/the-evolution-of-communication-and-why-stickers-matter/#6a5b7c582b2f (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Tang, Y., & Hew, K. F. (2019). Emoticon, emoji, and sticker use in computer-mediated communication: A review of theories and research findings. International Journal of Communication, 13, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y., Hew, K. F., Herring, S. C., & Chen, Q. (2021). (Mis)communication through stickers in online group discussions: A multiple-case study. Discourse & Communication, 15(5), 582–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., Chen, P., Meng, W., Zhan, X., Wang, J., Wang, P., & Gao, F. (2019). Associations among shyness, interpersonal relationships, and loneliness in college freshmen: A longitudinal cross-lagged analysis. Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, L. P., & Lajunen, T. (2010). Does Internet use reflect your personality? Relationship between eysenck’s personality dimensions and Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(2), 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völkel, S. T., Buschek, D., Pranjic, J., & Hussmann, H. (2019, October 1–4). Understanding emoji interpretation through user personality and message context. 21st International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services (MobileHCI’19), Taipei, Taiwan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, J. B. (1996). Computer-mediated communication: Impersonal, interpersonal, and hyperpersonal interaction. Communication Research, 23(1), 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Li, Y., Gui, X., Kou, Y., & Liu, F. (2019). Culturally-embedded visual literacy: A study of impression management via emoticon, emoji, sticker, and meme on social media in China. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3(CSCW), 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E. G. (1983). Adolescent loneliness. Adolescence, 18(69), 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D., Atkin, D. J., & Labato, L. (2023a). Gleaning emotions from virtual stickers: An intercultural study. Emerging Media, 1(1), 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D., Atkin, D. J., & Qin, Y. (2025). Is an emoji worth a thousand words in breaking the online spiral of silence? Cross-cultural comparisons of emoji use in online political discussion. Information, Communication & Society, 1–18. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1369118X.2025.2588355 (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Yang, D., Labato, L., Davis, S. M., & Qin, Y. (2023b). Cuteness in mobile messaging: An exploration of virtual “cute” sticker use in China and the U.S. International Journal of Communication, 17, 819–840. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D., & Liu, Y. (2024). A tale of three advantages: Cross-cultural recognition of basic emotions through virtual stickers. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 41(7), 3940–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D., Wu, T. Y., Atkin, D. J., Ríos, D. I., & Liu, Y. (2021). Social media portrait-editing intentions: Comparisons between Chinese and American female college students. Telematics and Informatics, 65, 101714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., Li, H., Han, L., & Yin, S. (2021). Relationship between big five personality and pathological internet use: Mediating effects of loneliness and depression. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 739981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).