Abstract

Putin’s Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 and launched a massive invasion of Ukraine in 2022. This study is predicated on framing theory, which posits that the media contribute to the creation of individuals’ perceived reality. We analyzed how the European press presented Russian President Vladimir Putin during both episodes. Content analysis was used to examine a sample of 1009 opinion articles and editorials published in two leading newspapers in each of the five largest European economies. Subsequently, we quantified the frequency of the predominant frames as well as the tone (positive, neutral, or negative) the articles struck towards Putin. The results show that many more articles were published in 2022 than in 2014, and that the degree of negative views of Putin is also more pronounced in 2022. In both instances, historical motives were most often employed to frame Putin’s actions, such as Putin’s urge to reassert Russian influence in the former Soviet space and his reaction to the alleged lack of recognition of Russia as a superpower.

1. Introduction

In February 2014, following the so-called Maidan Revolution, Russia initiated a process of annexation of the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea that culminated in mid-March when the Duma approved the incorporation of the territory into the Russian Federation. Eight years later, on 24 February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine. Vladimir Putin’s main justification for the aggression was to overthrow the alleged “pro-Nazi” regime of President Volodymir Zelensky, thereby protecting the population of the eastern Ukrainian Russian-speaking regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, whose independence the Kremlin had just recognized.

The 2022 invasion meant the outbreak of a new war on European territory, this time perpetrated by a nuclear superpower and permanent member of the UN Security Council and the G7. The reaction in Europe was one of alarm, indignation, and solidarity with the Ukrainian people. Most governments rushed to help Ukraine, even militarily, while European society, in general, turned to welcome refugees fleeing the war. Throughout this process, the media helped shape the public’s perception of the conflict.

The present study explores the way in which opinion articles in the European press have portrayed Vladimir Putin, his person, and the decisions he has made. A large sample of 1009 opinion articles, gathered from the time period just before and after each of the two aggressions in 2014 and 2022, was subjected to content analysis. We analyzed articles published in the most widely read newspapers in Germany, United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Spain.

Our results show that considerably more opinion pieces were printed in 2022 than in 2014, and that unfavorable views of Putin were more frequent and more pronounced in 2022 than in 2014. In both instances, Putin’s actions were predominantly attributed to historical motives: first and foremost, his impulse to reinstate Russian power in what he views as a former Soviet territory by rights, and his frustration at the alleged lack of recognition of Russia as a superpower after the Cold War. Among further motives for the aggression, we identified Putin’s desire to maintain and increase his political power by waging war to undermine domestic opposition, as well as his intention to weaken and destabilize the European Union and the Western alliance, which he views as a threat to his power. We are mindful that this negative portrayal of Putin’s actions may have contributed to Europe’s (EU and UK) reaction toward Russia, but further scientific studies should be carried out to confirm this cause-and-effect relationship, which cannot be deduced directly from our study.

2. Theoretical Framework/State of the Question

2.1. Framing and Media Effects

This study is predicated on the theoretical principle that the media contribute to shaping the perceived reality of their audiences. As early as 1922, Walter Lippmann (Lippmann, 1922) established the link between the media narrative and the representation of what happens in the world in his work Public Opinion.

Building on Lippman’s work, there is a substantial body of scholarship which explores the media’s impact on audiences’ opinions. Following a behaviorist approach, several scholars have explored the persuasive effect of the media and how this may result in a change of audiences’ mental states, thereby contributing to changing people’s behavior, which is indeed the ultimate goal of political communication (Lasswell, 1927; Lazarsfeld et al., 1948; Hovland et al., 1953; Katz & Lazarsfeld, 1955; O’Keefe, 1990).

Habermas (1962/1991) contributed to this debate by introducing the concept of the public sphere (Öffentlichkeit), the space where citizens identify and debate social issues of general interest, thus prompting and shaping political action. The role the media play in this process can hardly be overstated. It is therefore crucial to understand how the European media and their commentators frame Vladimir Putin and his war against Ukraine, as the particular frames chosen by the authors of the opinion pieces affect the readership’s perception and may determine the political decisions of their governments.

In the field of international relations, social constructivism (Wendt, 1999) must be added to the classical realist approach (Morgenthau, 1948; Waltz, 1979) and the liberal (Doyle, 1986; Keohane & Nye, 1977) approach. This current of thought argues that there is no objective social or political reality independent of our understanding of it. According to social constructivists, individuals as well as collectives help ‘construct’ the world in which they live and act. People’s beliefs and assumptions become especially consequential when they are widely shared. To this end, the media contribute greatly to enhancing the Habermasian public sphere. It is thus imperative to factor the media’s role into the social construction of a leader like Vladimir Putin and a country like Russia in European public opinion. Understanding how this image is constructed in the minds of European citizens through the frames offered by opinion makers may provide insight into the motives for the response of European governments and institutions. It follows that framing theory is an effective method for analyzing how the media present Putin to the European public.

In the 60s and 70s, agenda-setting became the predominant theoretical framework (Cohen, 1963; McCombs & Shaw, 1972). Some scholars view agenda-setting as the precursor to framing theory. For instance, McCombs, among others, argues that framing theory is an extension or equivalent to the so-called second level of agenda-setting (Lang & Lang, 1981; McCombs, 2004; McCombs & Ghanem, 2001). Both agenda-setting and framing are theories based on the mechanism through which the human brain retrieves and processes information. According to Semetko and Valkenburg, “framing analysis shares with agenda-setting research a focus on the relationship between public policy issues in the news and the public perceptions of these issues.” (Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000, p. 93) By highlighting certain topics, the media, whose impact is caused above all by their joint and aggregate action, facilitate the retrieval of information in the audience’s memory (Iyengar, 1990).

Our study is thus predicated on framing theory combined with content analysis. Chong and Druckman submit that “framing refers to the process by which people develop a particular conceptualization of an issue or reorient their thinking about an issue” (Chong & Druckman, 2007, p. 104). Scholars have proposed various definitions of framing in the media context. De Vreese holds that “framing involves a communication source presenting and defining an issue” (De Vreese, 2005, p. 51). Semetko and Valkenburg (2000) highlight the following definitions: “[frames are] conceptual tools which media and individuals rely on to convey, interpret and evaluate information” (Neuman et al., 1992, p. 60). Reminiscent of Habermas’ Öffentlichkeit, Tuchman submits that frames set the parameters “in which citizens discuss public events” (Tuchman, 1978, p. IV). Similarly, Goffman believes that frames are a useful device for audiences to “locate, perceive, identify, and label” information obtained through the media (Goffman, 1974, p. 21).

For our purposes, we part from the basis established by Entman, who states that

to frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described [original italics].(Entman, 1993, p. 52)

In 2003, Entman revisits the four framing effects he posited, and he concludes that

substantive news frames perform at least two of the following basic functions in covering events, issues, and political actors: (a) defining effects or conditions as problematic; (b) identifying causes; (c) conveying a moral judgment for those involved in the framed matter; and (d) endorsing remedies or improvements to the problematic situation.(Entman, 2003, p. 417)

We propose to prioritize Entman’s second (b) and third (c) functions of framing, seeing that both the annexation of Crimea and the invasion of Ukraine constitute highly “problematic situations” (a); indeed, in the articles we analyzed, we did not seek to identify proposed solutions to the crisis (d). Instead, we focused on identifying the causes of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine and instances of moral judgment, aspects which indeed abounded in the articles we examined.

Nevertheless, Sniderman and Theriault (2004) observe that often audiences are not exposed to a single frame on any issue. Rather, the media environment provides competing frames which not only compete with each other, but also display a dynamic nature. In fact, they evolve and transform over time, since they are the result of social interaction.

It bears noting that in our analysis we do not foreground the assessment of the cognitive effects that media news content has on individuals and how it shapes public opinion. Rather, we carry out an inductive study in which we employ content analysis to determine the main issue or topic frames (D’Angelo, 2018)—unlike the generic frames proposed by Entman—which prevail in the opinion pieces published in the main European dailies about Putin and his Ukraine policy. In our analysis of the 1009 texts in our sample, we are mindful of Tschirky and Makhortykh’s claim that: “framing is particularly effective for bringing together different interdisciplinary perspectives, in particular when used to study how specific phenomena (e.g., armed conflicts) are represented and not necessarily what are the effects of representation” (Tschirky & Makhortykh, 2024, p. 167).

Thus, by following the steps described by Chong and Druckman, we first identify an issue or event and, rather than speculating on the effects on the audience, “an initial set of frames for an issue is identified inductively to create a coding scheme” (Chong & Druckman, 2007, p. 107), which will then guide the content analysis that allows us to discern the specific issue or topic frames which ultimately determine the portrayal of Vladimir Putin’s policy towards Ukraine, always within the context of the problematization and moral judgment of the commentators.

Therefore, as opposed to the distinction between frames in communication and frames in thought (Druckman, 2001), our analysis is concerned with the first type, because we look at the words and arguments used in conveying the information rather than the cognitive process that takes place in the individual receiving the information.

Entman (1993, p. 52) distinguishes four locations where frames can be found in the communicative process: the communicator, the text, the receiver, and the culture. In our analysis, we give precedence to the second location—the text– and strive to determine the frames which emerge in it through inductive reasoning.

D’Angelo (2018) distinguishes four types of frames: journalist frames, issue frames, audience frames and news frames. According to this classification, our analysis is confined, as mentioned above, to the second type. These issue frames, also referred to as advocacy frames,

are held and expressed by individuals who construct an argument from considerations, which are reasons for favoring one side of an issue over another […]. Individuals, groups, or organizations typically express issue frames as informed opinions or policy statements relating to a topic, such as an event or issue, or a topic in which an event is linked to an issue.(D’Angelo, 2018, p. xxviii)

Unlike our study, most scholarly texts examine framing in straightforward news reporting, whereas we analyze editorials and opinion articles. In this genre, the frames (in the sense of perspectives from which realities are represented) are much more evident since an opinion piece is by definition a positioning on the part of the author on a particular issue or incident.

2.2. Vladimir Putin and the Media

The aim of our research is to analyze how the most prominent European newspapers have presented the figure of the Russian president to their readers. Several studies have pointed out the consistent negative portrayal of Russia, and particularly the Russian president, in the Western media. Seliverstova et al. (2021) analyzed digital editions of the Daily News (USA) and Der Spiegel (Germany) from 2000 to 2004 and 2018 to 2020. They observed that although certain linguistic resources displayed a more favorable image of the Russian leader in Der Spiegel between 2018 and 2020, they were rather marginal. The authors therefore concluded that the media deliberately constructs a predominantly negative image of Russia to influence the perceptions of English- and German-speaking audiences. This finding is corroborated by the work of Sahide and Muhammad (2023), who analyzed 120 news stories published between 15 February and 15 March 2022 by The Jakarta Post, Al Jazeera, Reuters, and The New York Times. According to their findings, these media outlets primarily depicted Russia as an aggressor and invader of Ukraine while also criticizing its policy measures.

Stovickova (2021) examines how Czech online news media presented Vladimir Putin over the course of three presidential elections using a Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) approach. The study detects a negative bias in the portrayal of Putin, Russian policies, and Russia, aligning closely with dominant Western media discourses. It found that overall, the media portrayed Putin as trying to restore Russia’s status as a global superpower, similar to the Cold War era, and revealed frequent use of sarcasm and negative tones throughout their coverage.

From a Russian perspective, Antonenkova (2019) scrutinized the portrayal of Putin in the U.S., British, and German press in 2015 on the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II. She concludes that the general tone was more negative in the U.S. press than in the European press, and that their reporting was conducive to what the author calls “conditions of confrontation.” Also from a Russian perspective, Oganesyan (2016) studies the image the Western press offered of Putin during the 2012 Sochi Olympics. Comstock (2022) examined journalists’ questioning of Presidents Putin and Dmitry Medvedev at international summits from 2000 to 2015 and detected what she calls “adversarial questioning”, which intensified progressively over the period she examined.

Another aspect of analysis pertinent to our research is the rhetorical recourse to history to legitimize Russian governmental decisions. Putin is in the habit of imparting lectures on Ukraine’s Russian past in order to justify the 2022 invasion and his push to regain control over Ukraine. Several studies delve into this aspect of Vladimir Putin’s policy: Pakhalyuk (2018) explores Putin’s excursions into history in his speeches from 2012 to 2018 and concludes that in his third presidential term a “securitization of historical memory” consolidated itself. What is more, Pakhalyuk found that Putin’s practice of brandishing historical arguments to justify far-reaching political decisions increased markedly over time. In a similar vein, Shiller (2023) argues that Putin’s Russia leverages the memory of World War II as a tool of counterrevolution. This involves highlighting Ukrainian antisemitism and Holocaust denial while simultaneously promoting a narrative of Russian victimhood in the current conflict with Ukraine. For Gatov (2016), the weight of history is starkly present in the image of Russia that is forged during Putin’s presidency with the manifest purpose of restoring the importance and exceptionality of his country.

Among other publications, we deem the following noteworthy: through content analysis, Oleinik (2023) has examined how the war speeches by the leaders of Russia, Ukraine, the United States, and the United Kingdom were covered in the media. He found that the propagandistic effect of the speeches decreases or increases in proportion to the degree of distortion with which the media convey the contents of the speech. The closer to the original, the higher the propagandistic effect. Demasi (2023) analyzes how Putin (and NATO) justify the actions taken in the context of the war of 2022 in their public statements. He concludes that both sides resort to three strategies: a morally justifying narrative, using precedent as pretext, and the adversaries’ threatening actions to justify one’s own course of action.

In documentary research which analyses 100 news articles published in Spanish, Escudero (2024) examines how the Russia-Ukraine conflict is framed for readers. The study finds that 85% of the analyzed content adopts a vocabulary aligned with war journalism, undermining the notion of mediation within the body of the news stories. Hanley et al. (2023) compare coverage of the Russian invasion of Ukraine across Western, Russian, and Chinese media ecosystems, highlighting that Western press outlets primarily emphasize the military and humanitarian dimensions of the war.

Focusing on the period between February 2014 and February 2015, Ojala et al. (2017) explore visual representations of the conflict in The Guardian, Die Welt, Dagens Nyheter, and Helsingin Sanomat, identifying three dominant frames: the Ukraine conflict as a national power struggle, as a case of Russian intervention, and as a broader geopolitical confrontation. Boyd-Barrett (2015) outlines ten key narratives that constitute the battleground of information warfare between nuclear powers, focusing specifically on mainstream Western media coverage of events in Crimea, Odessa, and Eastern Ukraine between February and October 2014.

Two studies stand out regarding the manner in which the invasion of Ukraine is framed in the social networks. The first is the aforementioned study on the siege of the city of Mariupol. It is predicated on the four types of frames distinguished by Entman, and it concludes that “the prevalence of human interest and conflict frames (…) aligns with earlier research on war framing in journalistic media” (Tschirky & Makhortykh, 2024, p. 163). The second study by Ptaszek et al. (2023) compares how the official Russian and Ukrainian agencies use Telegram to report on the war, concluding that the Russian agencies foreground military issues and international rivalry, while official Ukrainian posts on Telegram employ a moralizing framing of the conflict.

3. Research Question and Goals

The research question we pose is the following: How does the press of the five major European countries report on the Russian president in the context of the 2014 annexation of Crimea and the 2022 invasion of Ukraine in their opinion articles? We also compare both periods and the five countries among them, looking at the number of articles and the ensuing differences in tone.

However, the core of our research consists of finding the main frames through which the European op-ed leaders present Putin and his actions.

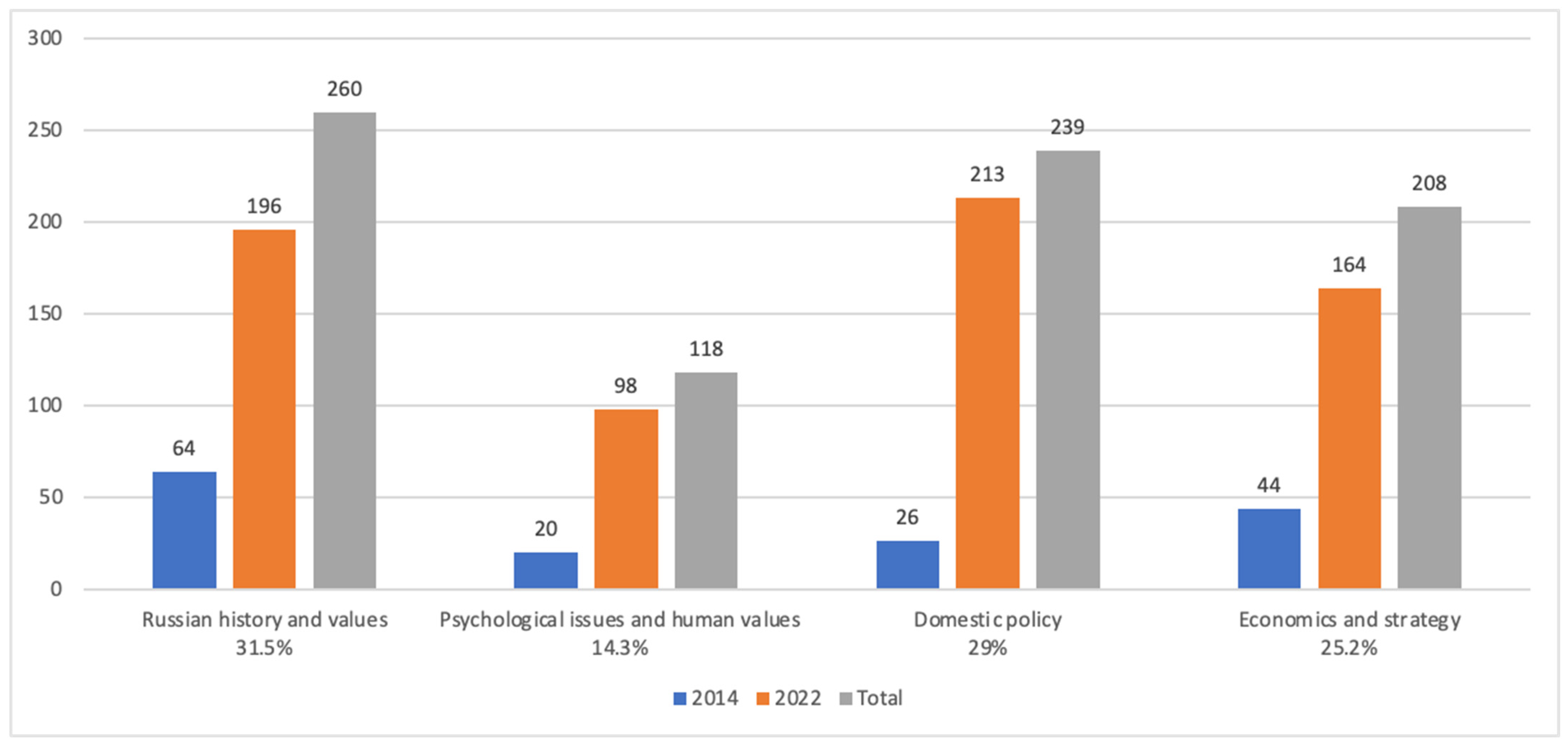

The inductive analyses we carried out rendered four frames favored by European commentators to elucidate Putin’s decisions in 2014 and 2022. We then quantified their emergence in the analyzed articles and editorials we examined. The four issue-specific frames we found were the following:

Frame 1: The main motivation for Putin’s aggressions identified by European commentators is the nostalgia for the hegemony of the Soviet Union and Russia’s desire to regain prominence in the international arena.

Frame 2: The main motivation for Putin’s aggressions identified by European commentators is the psychology behind his actions, his individual state of mind, and his ideology and values.

Frame 3: The main motivation for Putin’s aggressions identified by European commentators is his need to acquire absolute power and to eliminate all internal opposition.

Frame 4: The main motivation for Putin’s aggressions identified by European commentators is economic and geostrategic: to present himself as a hegemonic power vis-à-vis NATO and Europe. Putin seeks to counteract the threat posed by Europe by leveraging Europe’s energy dependence on Russia.

Once we identified the main frames, the goal of the research was to analyze and code the 1009 articles and editorials.

4. Methodology

4.1. Method

We analyzed the content of opinion articles (both those authored by individuals as well as those conveying the opinion of the paper) published in ten mainstream, opinion-leading newspapers published in the five largest European countries in terms of population and GDP. We drew our sample from two newspapers from each country. Germany: Die Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) and Die Süddeutsche Zeitung; the United Kingdom: The Times and The Guardian; France: Le Monde and Le Figaro; Italy: Corriere della Sera and La Repubblica; and Spain: El País and El Mundo.

The analysis of these newspapers centers on two moments of great tension in Europe: the first is the Russian offensive that ended in the occupation and annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014. We analyzed the time span from 24 February to 20 March (25 days). The second interval covers the attack on Ukraine in 2022. The 2022 dates match those in 2014, from 24 February to 20 March 2022 (also 25 days).

The newspapers were chosen because they are influential and historically renowned. They cover news in a similarly mainstream, conventional fashion, and they are among the most widely read newspapers in their respective countries. (ACPM, 2022; AIMC, 2022; Axel Springer, 2022; Ofcom, 2022; Prima Online, 2022). Another selection criterion was the political leaning of the two newspapers from each country. We sought to cover both the center-left and center-right of the political spectrum. Thus, Die Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, The Times, Le Figaro, El Mundo, and La Repubblica are representative of the conservative center-right, while the remaining five are considered progressive center-left newspapers (Sintes-Olivella et al., 2022). The selection includes newspapers which constitute examples of the three models of journalism identified and categorized in the benchmark study by Hallin and Mancini (2004).

To access the editorials and opinions pieces in our sample (n = 1009) we drew on the Factiva database as well as on research subscriptions. We searched in each of the ten newspapers for the keyword “Putin” and set the search parameters to the time intervals in question, and to the genres “commentary/opinion” and “editorial”. We removed repeated articles and those that did not fit the category “opinion article” or “editorial”. In some cases, we found that we needed to verify contents by consulting the digital archive of the newspapers or the print version.

A methodology based on content analysis (Bardin, 1977; Berelson, 1952; Brennen, 2022; Denzin, 2017; Jick, 1979; Krippendorff, 2004a; Weber, 1990), comprising both a quantitative and qualitative dimension, was used to analyze the selected sample, with each of the 1009 articles or editorials constituting a unit of analysis.

The authors conducted individual, interpretive content analysis. Each of the coders read the articles with the aim of identifying the fragments in which the authors presented Putin and his actions. The five authors held several norming sessions in order to elaborate and refine the analysis and to agree on criteria to identify the main frames in which Putin was presented to the readers in each of the respective countries. After the initial inductive analysis of a small sample of the selected articles, it was observed that some frames related to a specific issue appeared more frequently. For this reason, we resorted to determining frames which single out particular subject matters. We found four thematic frames, as shown in Table 1. Each author was assigned a country of publication and then analysed the entirety of the articles from each country, identifying in which of them the four main frames appeared.

Table 1.

Categories, subcategories, and analysis criteria for the sample of articles.

For our analysis, we employed spreadsheets for each newspaper and time interval with six categories per article (Table 1).

Lastly, we entered into the spreadsheets the main adjectives and epithets used in each article to characterize Vladimir Putin.

4.2. Reliability of the Results

To ensure the reliability of the coding of criteria we analyzed, part of the sample was subjected to a double-checking process (Kirk & Miller, 1986; Krippendorff, 2004b). Thus, of the 1009 total articles, 117 (11.6%) were re-coded by different researchers. The parts of the content analysis that underwent the double-checking process were the variables referring to the tone of the article (positive, negative, neutral) as well as the variables referring to the motives attributed to Putin for undertaking his actions.

The five authors themselves were responsible for carrying out the abovementioned double-checking, making sure the researcher who re-coded was not the same researcher who had done the original analysis. After re-coding, the percentage of coincidence between the coders was calculated using the formula: (coincidences/total re-coded articles) × 100.

The resulting coincidence rate was 90.71%, a level considered adequate in the scientific literature on interobserver reliability.

5. Results

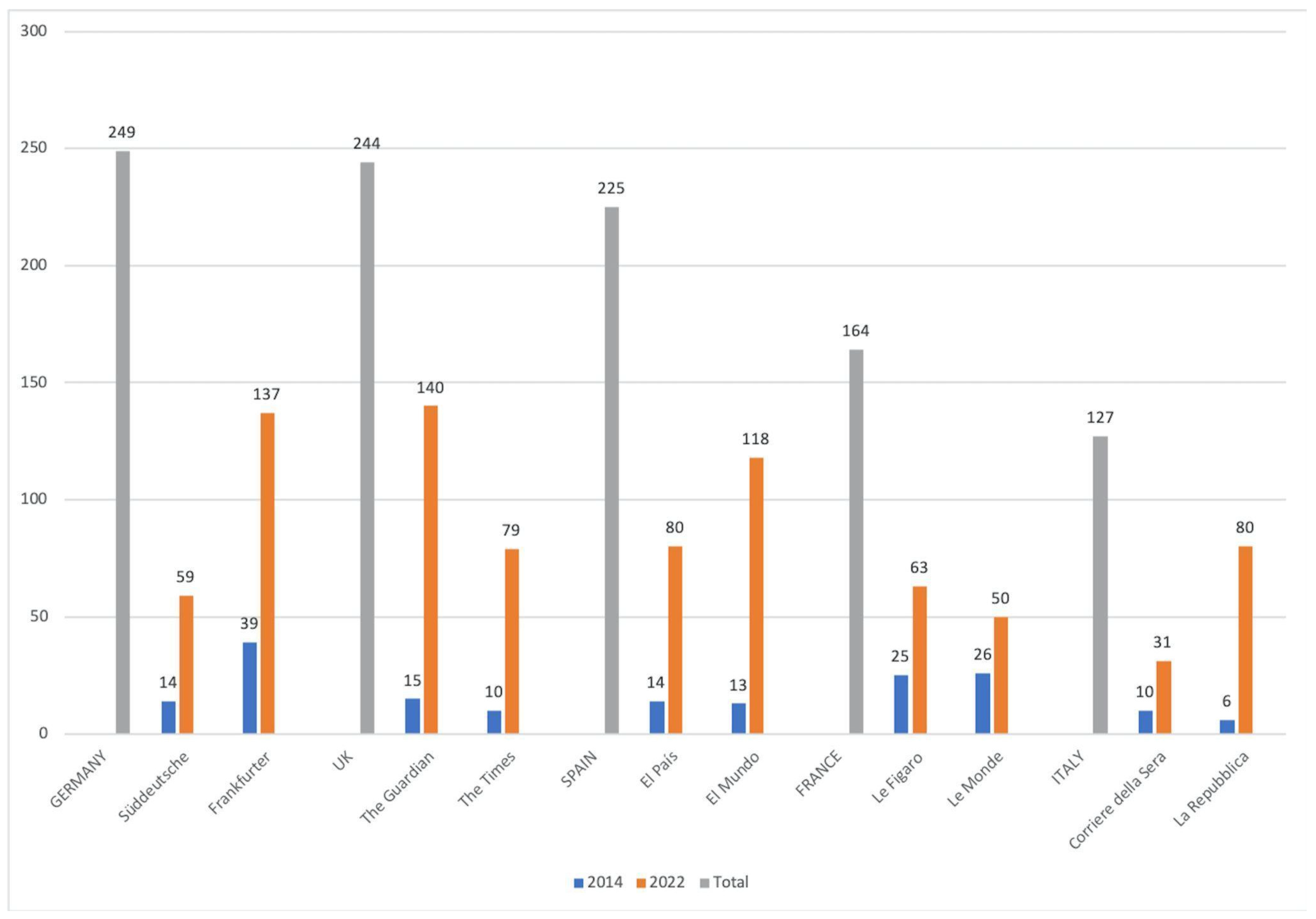

5.1. Germany

During the time intervals we chose to gather our sample, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and the Süddeutsche Zeitung published a total of 249 opinion articles which reference Vladimir Putin in the context of the 2014 and 2022 conflicts between Russia and Ukraine. The 2014 sample comprises a mere 53 (21.29%) articles, whereas in 2022 commentators dedicated 196 articles (78.71%) to the Russian aggression against Ukraine. Out of the 249 articles, 131 (52.61%) make some sort of reference to the possible motives that drove Vladimir Putin to annex Crimea and invade Ukraine. Out of these 131, in 2014, 35 (26.74%) articles attributed the reasons for the aggression to Putin personally, while in 2022, 96 (73.28%) articles referenced at least one of several aspects that may have prompted Putin to take military action.

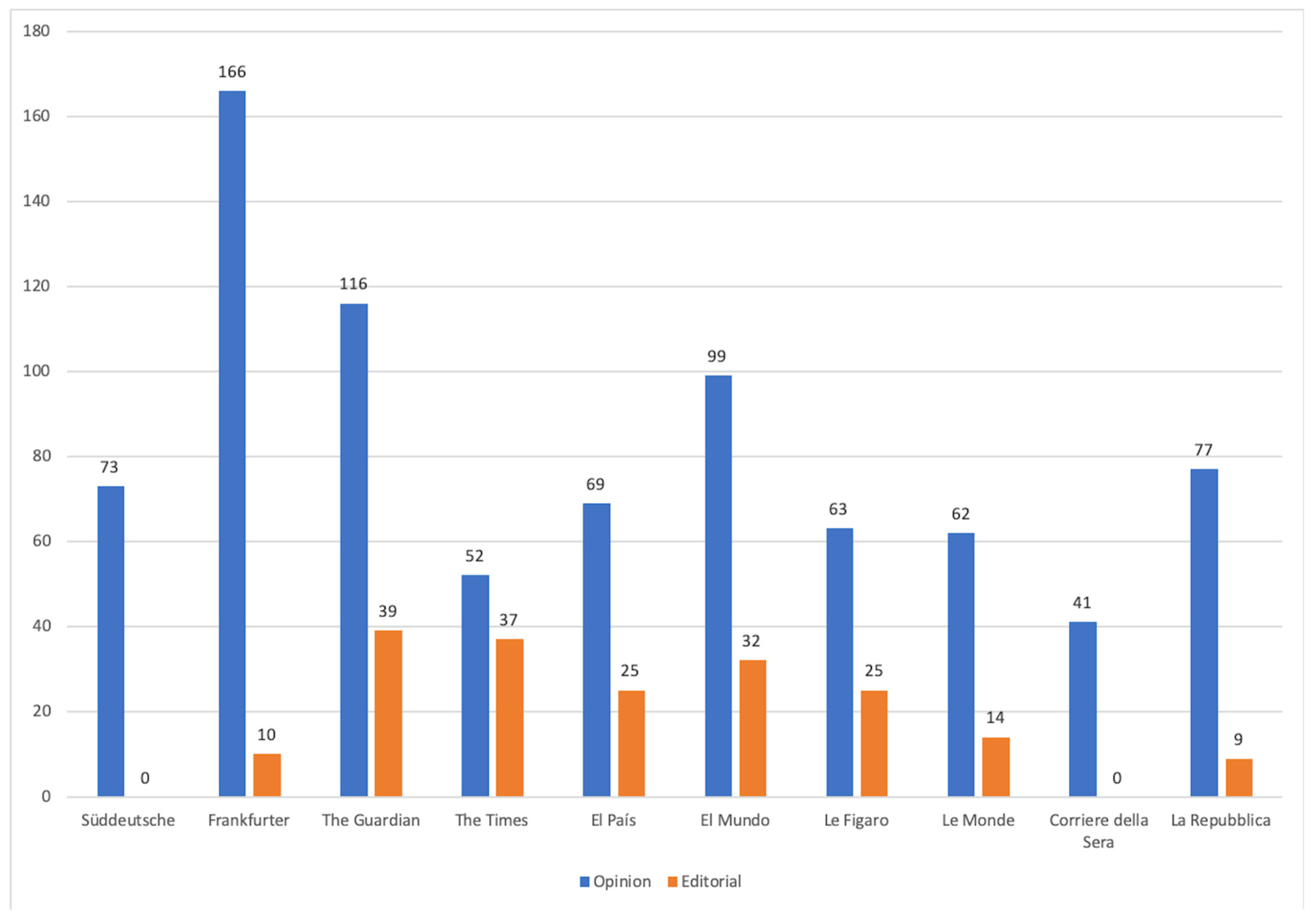

In 2014, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung published more than twice as many articles (38) as the Süddeutsche Zeitung (14) although the articles in the progressive Süddeutsche tended to be considerably longer. This disparity remained similar in 2022 with 59 articles published in the Süddeutsche, and 137 in the Frankfurter. Out of all the articles in the sample, 239 were opinion articles authored by one or several authors, and only 10 were editorials.

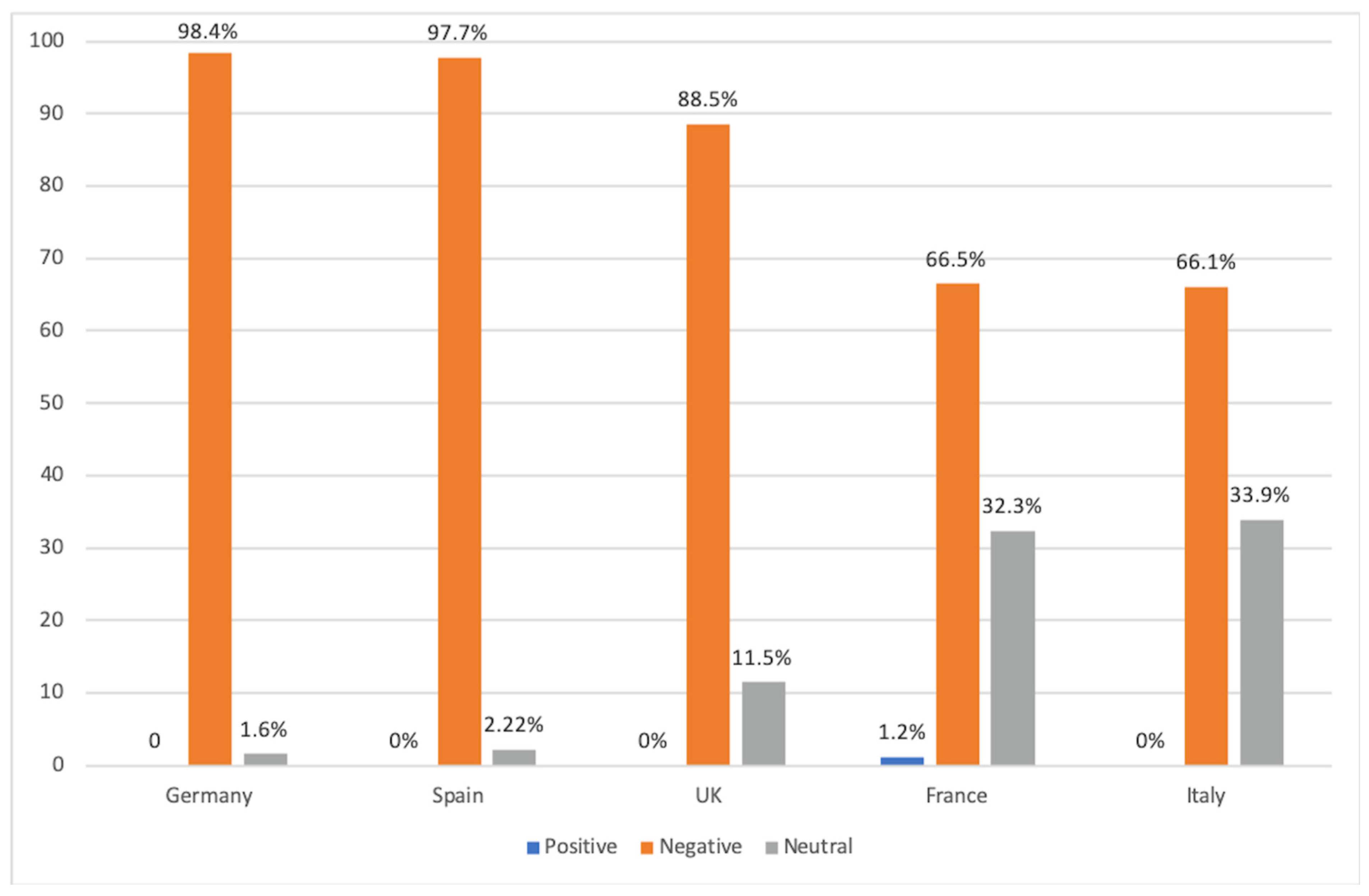

All but 4 of the 249 articles struck a negative tone regarding Vladimir Putin, that is to say they are somewhere on the spectrum between subtly critical or extremely critical of Russia and its president. In 2014, only one of the articles struck a neutral tone towards Putin, and in 2022 there were only three. None of the articles in the sample could be considered positive in tone regarding Putin in the sense that they condoned in any form the Russian military actions in 2014 and 2022. In 2022, the two German newspapers devoted four times as many articles to the conflict between the Russian Federation and Ukraine compared to 2014, the general tone, however, remained consistently negative.

It is worth recalling that the methodology of this study establishes that a maximum of two out of four categories of possible motives for Putin’s actions could be selected per article for the analysis. If more than two could be detected, the two most pronounced and salient aspects were chosen. Thus, in the 131 German articles which made mention of Putin’s motives, the total tally of references is 179, i.e., in the 131 articles, in 179 instances one or two of Putin’s motivational forces were quantified.

The main incentive for Putin to launch his invasions according to the articles in our sample, which emerged 58 times (32.40%), was rooted in Russian history, Russia’s grievances against the West, and the desire to restore Russia’s imperial greatness. Thus, Jürgen Kaube argues in the Frankfurter (25 February 2022) that “Putin can hardly be said to have concealed his conviction to make Russia Great Again and to deny Ukraine its right to exist.”

Tied for second place with 44 references each (24.58%) are two categories of incentives for military action. The first is predicated on Putin’s dictatorial style of government, quashing any opposition and dissident voices. The second category revolves around Putin’s desire to weaken and destabilize the EU, NATO, and Western democratic governments in general, which he regards as weak and outdated while at the same time perceiving them as a threat. Silke Bigalke (01 March 2022) writes in the Süddeutsche Zeitung, “With his attack on Ukraine, this ruler is demonstrating what the people of Russia have long felt: how much he despises, and probably even fears, democracy and freedom. Now the West expects Russians to protest against an apparatus of power that makes demonstrations more dangerous for participants year after year.”

And finally, 33 (18.43%) arguments pinpoint Putin’s personality, lack of morals, and his psychological condition as the main drivers of his military attack on Ukraine. Designations of his personality and state of mind mentioned in the German press include arrogance, thirst for power, megalomania, ruthlessness, narcissism, and egotism, to name just a few of a much longer list. Süddeutsche columnist Joachim Käppner gets to the heart of matter: “Russia is a major military power. It is unlikely that its president, who has abandoned all reason and morality, would stop his war of conquest because the West threatened him with fighter jets.”

As for the adjectives or epithets ascribed to the Russian president, the most frequent ones were those evoking his untruthfulness and mental instability, as well as his unscrupulousness in his power aspirations, a choice selection of which are as follows: mendacious, cruel, insane, sick, brutal, criminal, merciless, inhumane, despotic, gone wild, warmonger, neofascist, malicious, paranoic, barbaric—the list goes on.

5.2. Spain

In Spain, the newspapers El País and El Mundo published a total of 225 articles on Vladimir Putin and the conflict between Russia and Ukraine in the intervals we chose in 2014 and 2022. In 2014, there were 27 (12%), and in 2022, 198 (88%). Of the total of 225, 132 (58.66%) referred in one way or another to the reasons that led Vladimir Putin to launch attacks on Ukraine, with 22 articles (16.66%) issued in 2014 and 110 (83.33%) in 2022.

During the time interval we examined in 2014, the two newspapers published practically the same number of articles (14 El País and 13 El Mundo). In 2022, however, El Mundo published many more articles than its competitor, that is, 118 articles compared to 80 in El País. Overall, the number of opinion pieces (168) almost tripled the number of editorials (57).

Of the 225 articles, an overwhelming majority (220 = 97.77%) take a negative tone toward Putin, i.e., they are critical or very critical of Russia and the Russian president. Only 5 articles (2.22%) of neutral tone were found: 3 in 2014 and 2 in 2022. No articles with a positive tone, endorsing Russian action, were identified. Thus, not only did Spanish newspapers devote many more articles to the clash between the Russian Federation and Ukraine in 2022, but they also published more articles with a harsher tone toward Putin in 2022 compared to 2014.

Of the aforementioned 132 articles discussing Putin’s motives for his 2014 and 2022 attacks on Ukraine, most of them (out of a total of 179) referred to motives related to Russian history, Russian values, past grievances, or Putin’s imperialistic designs. These motives were identified 63 times (35.2%). An example of this frame arises in an article by Julián Casanova in El País (26 February 2022): “Putin wants to become the tsar of a rebuilt Russian empire”.

The second most frequent frame evokes the authoritarian nature of the Russian regime and Putin’s lack of respect for democracy. These aspects were identified in 55 articles (30.7%). Thus, an article by Iñaki Ellakuría in El Mundo (25 February 2022) finds that “[…] Putin’s objective, in order to guarantee the stability of his Stalinist autocracy, has always been the destruction of liberal democracy and its organs of consensus”.

Third place goes to economic and strategic motives (34 = 19.6%), while arguments pointing to Putin’s psychology as a cause of the conflicts with Ukraine number 26 (14.5%).

As for the adjectives or epithets dedicated to the Russian president, the most frequent were those referring to his dictatorial behavior such as “tyrant”, “criminal”, “Adolf Putin”, or “imperialist moron” to name a few.

5.3. France

French newspapers Le Figaro and Le Monde published a total of 164 articles and editorials in the two periods studied in 2014 and 2022. In 2014 they published 51 (31.1%), and in 2022, more than twice as many, 113 (68.9%). Out of the 164, 120 (73%) made unmistakable reference to Putin’s motivations for taking military action against Ukraine. Out of these 120 articles, 44 were published in 2014, and 76 in 2022.

No striking disparities can be discerned between the two publications for each period, although both published more articles when Russia attacked Ukraine in 2022. In 2014, Le Figaro published 25 articles and Le Monde 26, while in 2022, Le Figaro published a few more (63) than Le Monde (50). As for the distinction between opinion articles and editorials, a higher proportion of editorials appear in Le Figaro than in Le Monde. The difference is particularly noticeable in 2022, when in Le Monde only 9 of the 50 articles published are editorials (18%), compared to 19 of the total of 63 in Le Figaro (30.2%).

In two thirds of all articles (66.5%), the authors strike a negative tone toward Putin, and in the remaining third it is almost exclusively neutral (32.3%). However, in two texts from 2014, one from each newspaper, the authors take a favorable tone toward Putin (1.2%). Then again, rather than praising Putin or Russian action in Crimea, the occupation and subsequent annexation of the peninsula is justified on historical and cultural grounds.

In the majority of the 120 articles, Putin’s motivations for his aggressions against Ukraine are viewed as grounded in Russia’s history, past grievances, and nostalgia for tsarist Russia, the USSR, and the territory subjected to the Soviet yoke. This type of historical, nationalist, and imperialist rationale emerges in 68 (43.3%) of the 157 references we identified in the 120 articles. In El Figaro, for instance, Pierre Rouselin (6 March 2014) affirms that “in Vladimir Putin’s mind, the borders of Catherine II do exist. There can be no question of allowing them to disappear.”

The second most frequently referenced type of motivation (44 = 28%) is attributed to Putin’s geostrategic designs and his confrontation with Europe and the West in general, as well as the Kremlin’s (alleged) attempt to destabilize the EU by leveraging Europe’s dependence on Russian energy. Thus, Le Figaro’s Ivan Rioufol (11 March 2022) contends that “in his martial excess, Putin reveals the paranoid fury of a leader too long rejected by the West, and especially the United States.”

On 30 occasions a lesser, yet still significant, type of incentive for Putin’s aggressions emerges, largely to do with Russian domestic politics. Indeed, in 30 instances (19.1%), we identified references to Putin’s desire to neutralize his political opposition and to flaunt his dictatorial, anti-democratic power plays, which prove nothing short of catastrophic for the Russians themselves. Thus, Le Monde’s Arthur Larrue (3 March 2022) declares that “the Russians are not citizens; they are subjects who fearfully cower under cover.”

In only 15 instances (9.5%) do the articles in the French press allude to possible psycho-emotional issues affecting Putin’s conduct. Françoise Thorn, for instance, writes in Le Monde (5 March 2014) that Putin is driven by “a sense of insecurity and an unresolved post-imperial complex”.

In the two French newspapers, the most common epithets bestowed on the Russian president highlight his dictatorial, authoritarian, and violent behavior towards the neighboring country. By far the most common is “aggressor”, which appears up to 19 times in the two newspapers: 12 in Le Figaro and 7 in Le Monde, albeit solely in 2022, not in 2014. The second most common appellation is “autocrat,” which is used up to 10 times, in 2022 seven times in Le Monde alone, among others such as “tsar” and “dictator”.

5.4. Italy

A total of 127 articles referencing Vladimir Putin were gathered from the Italian Corriere della Sera (41 articles) and La Repubblica (86 articles). In 2014, 16 articles were published (12.6%) and in 2022, 111 (88.2%), suggesting an increased media interest in Vladimir Putin’s role during the invasion of Ukraine. Both in 2014 and in 2022 there is a predominance of opinion articles, 118 (92.9%), over editorials, 9 (7%) in the two newspapers. This points to a bid on the part of the print media to approach Putin from an individual and subjective perspective rather than the collective and consensual opinion of each newspaper.

The results show that in the two Italian newspapers the tone regarding Vladimir Putin is predominantly negative, accounting for 66.1% of the total number of articles we analyzed. Corriere della Sera strikes a harsher tone towards Putin with 78% of the articles taking a clearly unfavorable view, whereas in La Repubblica 60.5% convey a disapproving view. The percentages of publications with a neutral tone are significantly lower, representing 33.9% of the total sample, i.e., 22% of the articles in Corriere della Sera and 39.5% in La Repubblica. No articles with a positive tone were found, confirming that, overall, Italian dailies assumed a censorious stance towards Russia’s actions and policies during the 2014 and 2022 episodes.

Like the UK newspapers, the Italian press focuses mainly on Russia’s domestic policy in their criticism of Vladimir Putin. We found 84 mentions in 67 out of 127 articles (7 in 2014 and 60 in 2022). In 39 cases (46.4%) the president is portrayed as a dictator who represses the opposition and acts defying fundamental democratic values and international humanitarian norms. Indeed, Michele Serra in La Repubblica (3 March 2022) goes so far as to affirm that Putin “may not be Hitler, but he surely resembles him. So much so that he has dominated Russia for 22 years. And he was responsible for massacres in Chechnya and Syria, massacres of women and children, the destruction of cities and villages and systematic violations of human rights.”

The second most frequently referenced cluster of motives (22 = 26.2%) were those predicated on the economy as well as on Putin’s attempts to weaken and destabilize the Western world: “The aggression against Ukraine is a (deliberate!) attack on the European political order,” Corriere della Sera’s Federico Fubini (13 March 2022) observes, and he claims that Putin aims to “push more and more refugees into the Union, weaponizing them to destabilize our countries.”

While historical considerations rank first in Germany, France, and Spain, this frame ranks only third in the Italian newspapers. We counted 15 references (17.9%), for instance, in an article in Corriere della Sera (9 March 2022) in which Danilo Taino argues that “Vladimir Putin is waging yesterday’s war. Moved by the past and aiming at the past”, while “he would like to return to the reconstruction of a Russian-Tsarist or Russian-Soviet space, both erased by history”.

Lastly, there are those motives that allude to Putin’s psychology and human values, of which we found 8 mentions (9.5%). In another article by Michele Serra (La Repubblica, 3 March 2022) he writes that “Putin has reasoned and behaved more or less like the male who kills the mate who wants to leave him,” because for him “Ukraine either exists as ‘his’, or else it has no right to exist. Better dead than free”.

The Italian press variously dubbed Putin “dictator” (4), “tyrant” (4), “despot” (3), and “bloodthirsty” (3).

5.5. United Kingdom

The British newspapers The Guardian and The Times published 244 opinion articles and editorials addressing Putin and the aggressions against Ukraine in the period we explored. The vast majority (89.8%) appeared in 2022, while in 2014 there were only 25 articles (10.3%). In terms of distribution by newspaper, The Guardian leads with 155 (63.5%) articles in both time intervals, which almost double those in The Times (89 = 36.5%)

Opinion articles (168) make up 68.9%, while 79 (31.2%) are editorials. The ratio of editorials is higher in The Times, with 41.6% versus 25.2% in The Guardian.

A total of 88.9% of the articles in the two British newspapers strike a negative tone toward President Putin, condemning his actions in Ukraine. Only a small number (11.1%) of the articles are neutral. We did not identify any favorable views of Putin’s role in the conflict with Ukraine. Both newspapers printed mostly unfavorable opinion pieces. The progressive The Guardian printed more articles with a negative tone (94.2%) and thus took a noticeably harsher view of Putin than the conservative The Times (79.8%).

In 156 of the articles (16 in 2014 and 140 in 2022), we coded 206 references to Putin’s motives for the aggressions. The most recurrent (71 instances, corresponding to 34.5% of the total) cite Putin’s domestic policy, branding him as a dictator who tolerates no opposition and wields absolute control in the Kremlin. This view portrays Putin as a leader who disrespects Russian citizens and scoffs at the rules of democracy.

The second most frequently cited motive for Putin’s actions (63 instances, 30.6%) was his intention to weaken and destabilize the EU, NATO, and the West in general through economic and strategic means: “He believes that Russia is surrounded, threatened by an aggressive, expansionist NATO and needs to act to protect its borders, influence and global standing,” according to an editorial in The Times (28 February 2022).

The two remaining frames (Russian history and values/Putin’s frame of mind) were given equal importance and were cited 36 times each (17.5%). The commentators attribute to Putin nostalgia for the USSR and resentment over historical grievances. Thus, Geoffrey Robertson states in The Guardian (24 February 2014) that “Putin appears oversensitive to diplomatic slights, in part because he feels that since the collapse of the Soviet Union Russia has not been given sufficient respect in the international arena. His longing for respect partly explains his nostalgia for Soviet times and regret at the break-up of the Soviet empire”. Other commentators home in on Putin’s psychology, like The Times’ Ben Macintyre, (18 March 2022) who contends that “The fate of Ukraine will be settled on the battlefield but it is also being fought out in Putin’s mind, an organ shaped by the KGB and its history of internal treachery, paranoia and self-destruction”.

In both opinion articles and editorials, various appellations were used to describe Putin, most of which have a negative connotation. The most frequent terms were “evil” (7), “isolated” (6), “villain” (4), “paranoid” (4), “autocrat” (4), “authoritarian” (4), and “mad”/“madman” (4). Though less frequently, some articles featured neutral adjectives such as “rational”, “tactical”, “pragmatic”, or “oversensitive”.

5.6. Overall Results

The largest number of articles were printed in the two German newspapers (Table 2), 249 texts, followed by the United Kingdom (244), Spain (225), France (164), and, lastly, Italy (127). All five countries published far fewer texts in 2014 (172) than in 2022 (837). We saw the most striking contrast in the UK newspapers, where only 25 texts were printed in 2014 and 219 were printed in 2022. Similarly, the Italian newspapers printed only 16 articles in 2014 compared to 111 in 2022. In France, the gap was the smallest, with 51 articles in 2014 and 113 in 2022. In the two northern European countries (the UK and Germany), opinion leaders had a lot more to say about Putin than in the Mediterranean, although in 2022 Spanish newspapers came in second in numbers of articles printed, after the UK and closely followed by Germany. It would appear that the war that started in 2022, including its brutality, its effect on civilians, the glaring aggression, and lack of justification in the eyes of most Europeans, aroused much more output by print media commentators than the events of 2014.

Table 2.

Total number of articles by tone, country, and year.

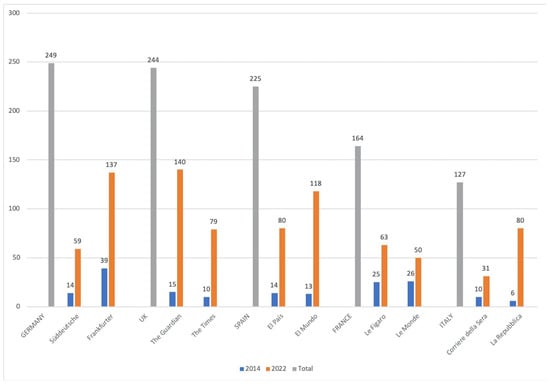

We ranked the newspapers irrespective of their country of providence (Figure 1) and found that the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung leads with 176 texts, followed by The Guardian with 155. Coming in last are Le Monde with 76, the Süddeutsche Zeitung with 73, and the Corriere della Sera with only 41 articles. If we look at 2022 alone, the ranking is the same. The newspapers that dedicated the largest number of opinion pieces to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine were the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, The Guardian, and the Spanish El Mundo, followed by El País tied with La Repubblica.

Figure 1.

Total number of publications by year, newspaper, and time interval. Source: the authors.

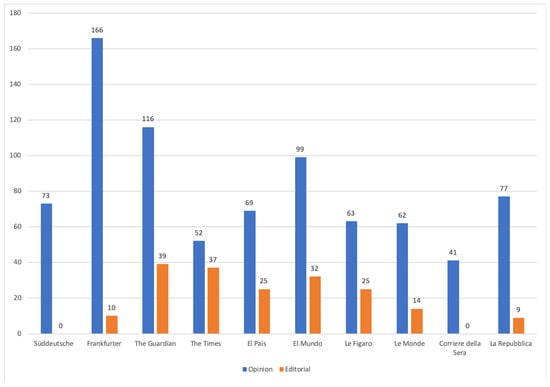

In both periods, and in all 10 newspapers (Figure 2), opinion articles vastly outnumbered editorials. Cases that stood out were El Mundo, which printed few articles, though more than twice as many editorials (9) than articles (4) in 2014, and the Corriere della Sera and the Süddeutsche Zeitung, which did not publish a single editorial in the two time spans we examined. Italy’s La Repubblica did not publish any editorials in 2014 and only 9 in 2022, compared to 71 opinion articles. Overall, the German print media had the lowest output of editorials, and the two British broadsheets the highest. The Times stands out for the highest editorial-to-article ratio (41.5%), with the added peculiarity that in 2014 it printed 9 editorials and only one opinion article.

Figure 2.

Total number of articles by genre (opinion articles vs. editorial) and newspaper. Source: the authors.

Since the United Kingdom and Italy are exemplars of different media systems according to the classification by Hallin and Mancini (2004), the notably higher output of editorials in the UK compared to the low yield in Italy merits further research.

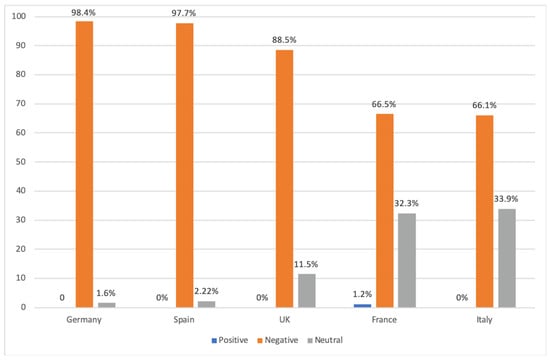

Across all countries, newspapers, and time spans (Table 2, Figure 3), the tone the commentators took toward Putin is overwhelmingly negative. Of the 1009 articles we analyzed, 875 (86.7%) were clearly disapproving, 132 (13%) were neutral, and only 2 French articles in 2014 (an insignificant 0.2%) struck a positive tone. In 2022, we could not identify any articles which in any way endorsed or supported Putin’s attack on Ukraine. In 2022, 88.7% of the articles censured Putin, while in 2014, 77% did so. Among the five countries, Germany and Spain were the most critical, followed by the United Kingdom. Italy and France were the countries that were least critical of Putin. The Italian newspapers printed fewer censorious articles than any other press, yet, unlike in two French articles we found, they did not actually go so far as to show approval for Putin’s actions.

Figure 3.

Percentage of publications by tone and country. Source: the authors.

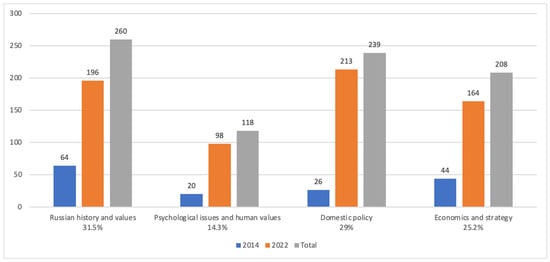

Lastly, we scrutinized each article for references to the four frames we established at the outset (Figure 4) and we entered a maximum of two (the most prominent) in our spreadsheets. Overwhelmingly, the articles framed the Russian aggressions against Ukraine either in terms of Russian/Soviet history or in the interest of domestic policy, or both. A total of 31.5% of the most recurrent arguments evoked Russia’s historical grievances (frame 1): USSR nostalgia, willingness to restore Soviet strength over its former area of influence, Soviet-style domination of Russia’s neighbors, or traditional imperialism rooted in the tsarist era, and Putin’s imperative to protect Russians abroad. Some pundits even saw similarities to Nazi expansion in the 1930s.

Figure 4.

Number of publications by frame across all newspapers in 2014 and 2022. Source: the authors.

A total of 29% of the articles allude in some fashion to Russia’s domestic policy (frame 3): Putin acts internally as a dictator and ruthlessly suppresses all opposition; Russia acts as a totalitarian regime, scoffing at basic democratic values.

A total of 25.2% of the articles authored by European commentators couch the conflict in an economic and geostrategic context (frame 4). Thus, Putin aims to weaken or destabilize the EU, NATO, and “the Western world” in general. Several writers stress that Putin is leveraging energy resources against Europe. The motivations identified in this category also include that, notwithstanding Putin’s assessment of Western regimes as weak and outdated, he cannot help perceiving them as a threat. This may account for Putin frequently flaunting disrespect for international law and the sovereignty of neighboring countries, as many commentators point out.

Not as frequent as frames 1–3, though still significant, are references to frame 2: Putin’s psychology, personal attributes, and moral values. A total of 14.3% of the articles are framed in terms of personality defects such as arrogance, ambition, lust for power, egotism, narcissism, intolerance, and anti-democratic attitudes.

Depending on the country, commentators prioritize the four frames differently. Frame 1, Russian history and values, is the most frequently referenced in France, Germany, and Spain, while in the United Kingdom and Italy frame 1 ranks third. In these two countries, frame 3 (Domestic policy) is prioritized, followed by frame 4 (Economics and strategy). In Spain and Germany, domestic policy ranks second, while in France, economics and strategy ranks second. In all five countries, the least mentioned frame corresponds to Putin’s psychology and personality defects.

In 2022, the framing that gains the most traction is the one portraying Putin as a dictator who crushes internal opposition, who governs as a totalitarian ruler, and who disrespects Russia’s neighbors. Compared to 2014, the number of references to this frame are eight times higher, rising from 26 to 213 (Figure 4). In second place, the frame casting him as arrogant, ambitious, irresponsible, narcissistic, or selfish increases five-fold. Although this portrayal is the least frequent overall, it is noteworthy because references to Putin’s personal defects increase sharply after the Ukraine invasion, almost as much as the references to his dictator-style ruling of Russia. This may be accounted for by opinion leaders accepting a fait accompli in 2014, and perhaps giving Putin the benefit of the doubt. However, when in 2022 a full-scale invasion of a sovereign European country reignited Cold War fears, Russia’s aggressiveness could no longer be denied, and Putin was unequivocally recognized as an authoritarian dictator and as a threat to European democracies. Commentators no longer held back their anger and frustration at the Russian president’s unforgiveable aggression.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

As our findings bear out, in the time before and after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the major European newspapers published many more opinion articles and editorials about Vladimir Putin than before and after the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014.

The tone of the articles was much more negative in 2022 than in 2014. In both periods, the predominant tone was negative towards Putin, but the disapproval and condemnation of Putin was significantly more severe in 2022, when almost nine out of ten texts were negative. This finding is in line with previous studies, which also highlight the disapproval with which Putin and Russia are presented to Western readerships (Seliverstova et al., 2021; Sahide & Muhammad, 2023; Stovickova, 2021).

None of the articles and editorials from 2022 submit arguments which might go some way to endorsing or justifying the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. By contrast, we did find articles published in 2014 which hazarded such arguments, reminding readers of the Russianness of Crimea and pointing out that more than 90% of the Crimean population is Russian speaking, and many feel a sense of belonging to Russia rather than Ukraine.

Upon concluding our content analysis, the framing of Putin’s role as we observed it in the articles can be parsed as follows:

Two frames stand out clearly in the 1009 journalistic texts we analyzed: frame number 1 and frame number 3. The most frequently applied frame (number 1) portrays Putin as yearning for the glorious Soviet past, greedy for power and influence over Eastern Europe. He reacts to what he claims is a threat emanating from the West, accusing the Western world of striving for domination by seeking to expand the Atlantic Alliance to Ukraine. The authors of these articles frame their coverage of Putin’s actions as those of a nostalgic heir to the Soviet era, when the Kremlin wielded absolute control of the 15 republics of the USSR. Thus, after the end of the Cold War in 1991, the Balkan wars of the 1990s, and the expansion of NATO, Putin feels that Russia has ceased to be a decisive player on the world stage, a state of affairs he is determined to put right. This assessment tracks with findings by Stovickova (2021) in her studies on Czech online news media.

Frame 3 brands Putin as a dictator, who flaunts his disdain for democratic values, democracy, and freedom, and who crushes internal opposition, just as he denies the sovereignty of neighboring Ukraine. Already, in 2014, he annexed the Crimean peninsula. In 2022, he launched a massive military attack on Ukraine with the pretext (entirely unconvincing to European commentators) of overthrowing an alleged pro-Nazi Zelensky regime and protecting the Russophone population of the independent republics of Donetsk and Luhansk.

Frame 4, ranked third in our quantitative analysis, frames Putin’s actions as a result of pragmatic motives predicated on economic and geo-strategic factors. This category of framing overlaps to a certain degree with frame 3 in that Putin perceives the Western countries as a threat which would culminate in Ukraine joining NATO and the European Union. According to many pundits who favor this frame, Putin is determined to destabilize and weaken the Western alliance by leveraging the flow of Russian energy resources, in particular the gas supply on which many European countries, above all Germany, depend. Hence, Putin’s objectives owe more to geopolitical and economic considerations and less to the dictates of domestic policy, his thirst for unchecked power, or reclaiming the vast hegemony of the Soviet era.

Finally, frame 2 (ranked 4th), credits Putin’s aggressive actions to psychological motives, to his personality, and moral values, or lack thereof. Many of the adjectives and epithets ascribed to Putin contribute significantly to this frame. They account to a large degree for the negative tone emanating from the authors of the articles. A selection of the choicest appellations on a very long list would include cruel, criminal, paranoid, autocrat, tyrant, dictator, despot, aggressor, bloodthirsty, and inhuman.

We submit that our study confirms the applicability of framing theory and the method of content analysis for the study of journalistic opinion texts. As we have made clear at the outset, it was not the objective of this study to gauge the media effects, nor the way in which the articles in our sample sought to condition the opinions of the European public. We would be remiss, however, if we did not point out that an opinion poll carried out by the European Council on Foreign Relations (Puglierin & Zerka, 2023) seems to confirm that the opinion of Europeans regarding Russia worsened in 2023 compared to 2021. According to this study, in the EU member states “a majority agrees that Russia is their country’s -and Europe’s- “adversary”, with Germany proving to be one of “the main hawks in this respect”. Puglierin and Zerka also state that “on average, the share of respondents who see Russia as Europe’s “rival” or “adversary” has increased from around one-third to almost two-thirds. At the same time, sympathies towards Russia have dropped considerably”, from 2021 to 2023. The European Union Eurobarometer published in December 2023 confirms that support for Ukraine prevails among EU citizens: “almost nine in ten (89%) agree with providing humanitarian support to the people affected by the war, and more than eight in ten (84%) agree with welcoming into the EU people fleeing the war” (European Commission, 2023).

The data obtained in our study highlight the demand for further research into the role the media have played in the decline of Russia’s image among European opinion leaders. Our research has yielded robust, quantifiable results which substantiate the impact of framing on the treatment and portrayal of Vladimir Putin’s person in the opinion articles and editorials printed in the major daily newspapers from the five largest countries and leading economies in Europe.

Nevertheless, some considerations may be in order. The authors believe that this study contributes to highlighting the political significance of media framing in liberal democracies. By framing Putin as an aggressive leader, as an autocrat, as an imperialist, as nostalgic of the past glory of the USSR, European commentators do much more than interpret a political event. They participate in the construction of the political legitimacy and moral responsibility on which Europe bases its response to Russian aggression. The act of framing Putin’s actions has consequences for public opinion and government policy decisions: when European newspapers overwhelmingly adopt frames of moral condemnation, these frames can help justify government responses such as sending military aid to Ukraine, increasing military spending, and (in the 2025 context of Trump’s U.S. shift away from Europe) creating a sense of danger and threat that justifies rearmament in the face of a potential Russian enemy.

The stance of the major European newspapers, their readership, and their countries’ leaders likewise appears to align and maintain coherence over time. The responses of these three actors thus evolved jointly, shifting from a less forceful position in 2014—where some room for doubt regarding the Kremlin’s true intentions still remained—to a much firmer and more unanimous moral condemnation of Putin following the 2022 invasion. In line with, and influenced by, the positions of the media and the public, political leaders also reacted in markedly different ways to the first and second instances of Russian aggression.

From the constructivist perspective of international relations, the identity of international actors is not naturally fixed but socially constructed, so that the way Putin and Russia are framed contributes to the formation of the identities of us (Europe) and the other (Russia). Thus, in this context, the image of Putin in the media contributes to reinforcing European identity as a democratic, peaceful space based on the rule of law and individual freedom, as opposed to a Russia ruled by a revisionist dictator who violated international law and invaded a sovereign neighbor. Foregrounding Putin’s nostalgia for the Soviet era also places him outside the post-1990 international order, thereby establishing a clear good–bad or civilized–barbaric dichotomy, thus reaffirming the identity of a modern, 21st century Europe, based on democratic values, versus an archaic Russia, ruled by an autocratic, violent, and repressive leader of his people and his neighbors.

Therefore, the media’s framing of Putin as an aggressive leader may have a performative consequence, as it constructs the discourse on which governments’ decisions, negotiations and mediations in the international public sphere are based.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.F. and M.S.-O.; Methodology, P.F., M.S.-O., K.Z., V.L. and E.Y.-P.; Validation, P.F. and M.S.-O.; Formal analysis, P.F., M.S.-O., K.Z., V.L. and E.Y.-P.; Investigation, P.F., M.S.-O., K.Z., V.L. and E.Y.-P.; Resources, P.F., M.S.-O. and K.Z.; Writing–original draft, P.F., M.S.-O., K.Z., V.L. and E.Y.-P.; Writing–review & editing, K.Z.; Visualization, V.L.; Supervision, P.F.; Project administration, P.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- ACPM. (2022, February 24). Ranking of national daily newspapers in paid outreach in France in 2021, by daily circulation volume [Graph]. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/784974/paid-circulation-volume-national-dailies-by-publication-france/ (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- AIMC. (2022, March). Number of daily readers of the leading newspapers in Spain in 3rd quarter 2021 (in 1000s) [Graph]. Statista. Available online: https://www-statista-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/statistics/436643/most-read-newspapers-in-spain/ (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Antonenkova, A. S. (2019). Foreign media about the Great Patriotic War in the context of information confrontation. Theoretical and Practical Issues of Journalism, 8(3), 608–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axel Springer. (2022, July 27). Ma 2020 Pressemedien II: Reach of national daily newspapers in Germany (in million readers) [Graph]. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/417363/national-daily-newspapers-reach-in-germany/ (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Bardin, L. (1977). L’analyse de contenu [Content analysis]. Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Berelson, B. (1952). Content analysis in communication research. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Barrett, O. (2015). Ukraine, mainstream media and conflict propaganda. Journalism Studies, 18(8), 1016–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennen, B. S. (2022). Qualitative research methods for media studies (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, D., & Druckman, J. N. (2007). Framing theory. Annual Review of Political Science, 10, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B. C. (1963). The press and foreign policy. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Comstock, L. (2022). Journalistic practice in the international press corps. Adversarial questioning of the Russian president. Journal of Language Aggression and Conflict, 11(2), 145–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, P. (2018). Prologue: A typology of frames in news framing analysis. In P. D’Angelo (Ed.), Doing news framing analysis II. Empirical and theoretical perspectives (pp. 23–40). Routledge. ISBN 978 1 315642239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demasi, M. A. (2023). Accountability in the Russo-Ukranian War: Vladimir Putin versus NATO. Peace and Conflict. Journal of Peace Psychology, 29(3), 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N. K. (2017). Critical qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(1), 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vreese, C. H. (2005). News framing: Theory and typology. Information Design Journal, 13(1), 51–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, M. W. (1986). Liberalism and world politics. American Political Science Review, 80(4), 1151–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Druckman, J. N. (2001). The implications of framing effects for citizen competence. Political Behavior, 23(3), 225–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R. M. (2003). Cascading activation: Contesting the White House’s frame after 9/11. Political Communication, 20(4), 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, C. (2024). Media coverage of mediation: Before and during the Russian–Ukrainian War. Horizons of Politics, 15(51), 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2023, December). Standard Eurobarometer 100—Autumn 2023. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/3053 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Gatov, V. I. (2016). Contagious tales of Russian origin and Putin’s evolution. Society, 53, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. (1991). The structural transformation of the Public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society (T. Burger, & F. Lawrence, Trans.). MIT Press. (Original work published 1962). [Google Scholar]

- Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley, H. W. A., Kumar, D., & Durumeric, Z. (2023). “A Special Operation”: A Quantitative Approach to Dissecting and Comparing Different Media Ecosystems’ Coverage of the Russo-Ukrainian War. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 17(1), 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C. I., Janis, I. L., & Kelley, H. H. (1953). Communication and persuasion. Psychological studies of opinion change. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar, S. (1990). The accessibility bias in politics: Television News and public opinion. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 2(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jick, T. D. (1979). Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: Triangulation in action. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(4), 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E., & Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1955). Personal influence. The part played by people in the flow of mass communication. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keohane, R. O., & Nye, J. (1977). Power and interdependence: World politics in transition. Little Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, J. M., & Miller, M. (1986). Reliability and validity in qualitative research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. (2004a). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. (2004b). Reliability in content analysis. Human Communication Research, 30(3), 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, G. E., & Lang, K. (1981). Watergate. An exploration of the Agenda-Building process. In C. G. Wilhoit, & H. De Bock (Eds.), Mass communication review yearbook 2 (pp. 447–469). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lasswell, H. D. (1927). Propaganda technique in World War I. Paul Kegan. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld, P. F., Berelson, B., & Gaudet, H. (1948). The people’s choice. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann, W. (1922). Public opinion. Harcourt, Brace and Company. [Google Scholar]

- McCombs, M. (2004). Setting the Agenda. The mass media and public opinion. Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCombs, M., & Ghanem, S. I. (2001). The convergence of Agenda setting and framing. In S. D. Reese, O. H. Gandy Jr., & A. E. Grant (Eds.), Framing public life: Perspectives on media and our understanding of the social world (pp. 67–82). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McCombs, M., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(2), 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenthau, H. (1948). Politics among nations. McGraw-Hill, Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, W. R., Just, M. R., & Crigler, A. N. (1992). Common knowledge. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ofcom. (2022, July 21). Daily newspapers most used for news in the United Kingdom (UK) as of March 2022 [Graph]. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/376224/leading-daily-newspapers-used-for-news-in-the-uk/ (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Oganesyan, K. S. (2016). Political leadership and media as a tool for Politicians’ image-reflection. Theoretical and Practical Issues of Journalism, 5(2), 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M., Pantti, M., & Kangas, J. (2017). Whose war, whose fault? Visual framing of the Ukraine conflict in Western European newspapers. International Journal of Communication, 11, 474–498. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe, D. J. (1990). Persuasion: Theory and research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Oleinik, A. (2023). War propaganda effectiveness: A comparative content-analysis of media coverage of the two first months of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 32(4), 526–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakhalyuk, K. A. (2018). Historical past as foundation of Russia’s polity (Assessing Putin’s speeches in 2012–2018). Politeia-Journal of Political Theory, Political Philosophy and Sociology of Politics, 91(4), 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prima Online. (2022, January 25). Leading news websites in Italy in November 2021, by number of daily users (in thousands) [Graph]. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/729607/top-15-news-websites-in-italy/ (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Ptaszek, G., Yuskiv, B., & Khomych, S. (2023). War on frames: Text mining of conflict in Russian and Ukrainian news agency coverage on Telegram during the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Media, War & Conflict, 17(1), 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglierin, J., & Zerka, P. (2023, June 7). Keeping America close, Russia down, and China far away: How Europeans navigate a competitive world. European council on foreign relations. Available online: https://ecfr.eu/publication/keeping-america-close-russia-down-and-china-far-away-how-europeans-navigate-a-competitive-world/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Sahide, A., & Muhammad, A. (2023). Global media framing Russian invasion of Ukraine. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 12(4), 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seliverstova, L., Levitskaya, A., & Seliverstov, I. (2021). Media representation of the image of the Russian political leader in western online media (On the Material Daily News and Der Spiegel). International Journal of Media and Information Literacy, 6(2), 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semetko, H. A., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2000). Framing European politics: A content analysis of press and television news. Journal of Communication, 50(2), 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiller, S. (2023). Second World War memory as an instrument of counter-revolution in Putin’s Russia. Canadian Slavonic Papers, 65, 432–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintes-Olivella, M., Franch, P., Yeste-Piquer, E., & Zilles, K. (2022). Europe Abhors Donald Trump: The opinion on the 2020 U.S. presidential elections and their candidates in the European newspapers. American Behavioral Scientist, 66(1), 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniderman, P. M., & Theriault, S. M. (2004). The structure of political argument and the logic of issue framing. In E. S. Willem, & M. S. Paul (Eds.), Studies in public opinion (pp. 133–165). Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stovickova, Z. (2021). ‘Model Putin Forever’. A critical discourse analysis on vladimir Putin’s portrayal in Czech Online news media. Central European Journal of Communication, 14, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschirky, M., & Makhortykh, M. (2024). #Azovsteel: Comparing qualitative and quantitative approaches for studying framing onf the siege of Mariupol on Twitter. Media, War & Conflict, 17(2), 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuchman, G. (1978). Making news. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waltz, K. (1979). Theory of international politics. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic content analysis. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Wendt, A. (1999). Social theory of international politics. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).