1. Introduction

The proliferation of artificial intelligence technologies in Indonesian media landscapes presents unprecedented opportunities and complex challenges for public information resilience. As Indonesia continues its digital transformation journey, with internet penetration reaching 79.5% by 2024 according to the Indonesian Internet Service Providers Association (

Santika, 2024), the intersection of AI adoption and digital literacy becomes increasingly critical for maintaining information integrity (

Sutrisno, 2024). The emergence of generative AI technologies has fundamentally altered how information is created, disseminated, and consumed, creating new vulnerabilities in an already complex information ecosystem.

Recent developments in Indonesia’s media landscape demonstrate the urgency of understanding these dynamics. The country has experienced significant challenges with misinformation and disinformation, particularly during major political events and health crises (

Lim, 2017). The COVID-19 pandemic further highlighted the vulnerability of Indonesian society to false information, with various studies documenting widespread circulation of health-related misinformation across digital platforms (

Juditha, 2018;

Nasir et al., 2021). Against this backdrop, introducing AI technologies presents a paradox where the technologies promoted as solutions to misinformation challenges may inadvertently create new forms of information vulnerability.

The Indonesian media’s approach to covering AI technologies reflects broader global patterns while maintaining distinct local characteristics. Indonesian journalism has traditionally played a crucial role in shaping public understanding of technological innovations, often serving as the general population’s primary source of information about complex technical subjects (

Sen & Hill, 2000). However, rapid AI development has challenged traditional journalistic practices, requiring reporters to navigate unfamiliar technical territories while maintaining accuracy and accessibility in their coverage.

Digital literacy levels in Indonesia present a complex picture that varies significantly across demographic and geographic lines. While urban areas, particularly in Java, demonstrate higher digital literacy rates, rural regions and older populations face substantial challenges navigating digital information environments (

Kurnia & Astuti, 2017). This digital divide becomes particularly problematic when considering AI technologies, which require a sophisticated understanding of algorithmic processes, data sources, and potential biases to evaluate critically.

Information resilience has gained prominence in media studies as researchers seek to understand how societies can maintain information integrity in increasingly complex digital environments (

Humprecht et al., 2020). Information resilience encompasses the ability to identify false information and the capacity to adapt to new forms of information manipulation and maintain trust in legitimate information sources. In AI technologies, information resilience requires understanding how these systems work, their limitations, and their potential for beneficial and harmful applications.

This study draws primarily on media framing theory (

Entman, 1993), which provides insights into how journalistic choices shape public understanding of complex issues. The combination of framing analysis with digital literacy measurement represents a novel methodological approach examining media production and audience reception processes.

Diakopoulos (

2019) notes that “The increasing reliance on algorithmic systems for information processing and dissemination creates new challenges for maintaining transparency and accountability in news production”. This observation becomes particularly relevant in the Indonesian context, where rapid AI adoption in media organizations has often proceeded without corresponding investments in public education or professional training (

Newman, 2024).

This study addresses a critical gap in understanding how media narratives about AI technologies influence Indonesia’s public digital literacy and information resilience. While previous research has examined either AI adoption patterns or digital literacy levels independently, limited attention has been paid to their interconnected dynamics and combined impact on information vulnerability. The Indonesian context provides a particularly valuable case study due to the country’s position as a rapidly developing digital economy with diverse linguistic, cultural, and educational backgrounds.

Three primary research questions guide this study: How do Indonesian media outlets frame artificial intelligence technologies about information challenges and solutions? Second, what is the relationship between exposure to AI media narratives and individual digital literacy levels among Indonesian internet users? Third, how do these factors influence information resilience and vulnerability to misinformation in different demographic segments of Indonesian society? The main objective is to provide empirical evidence for developing evidence-based policies and educational interventions to enhance information resilience in AI-mediated environments.

6. Conclusions

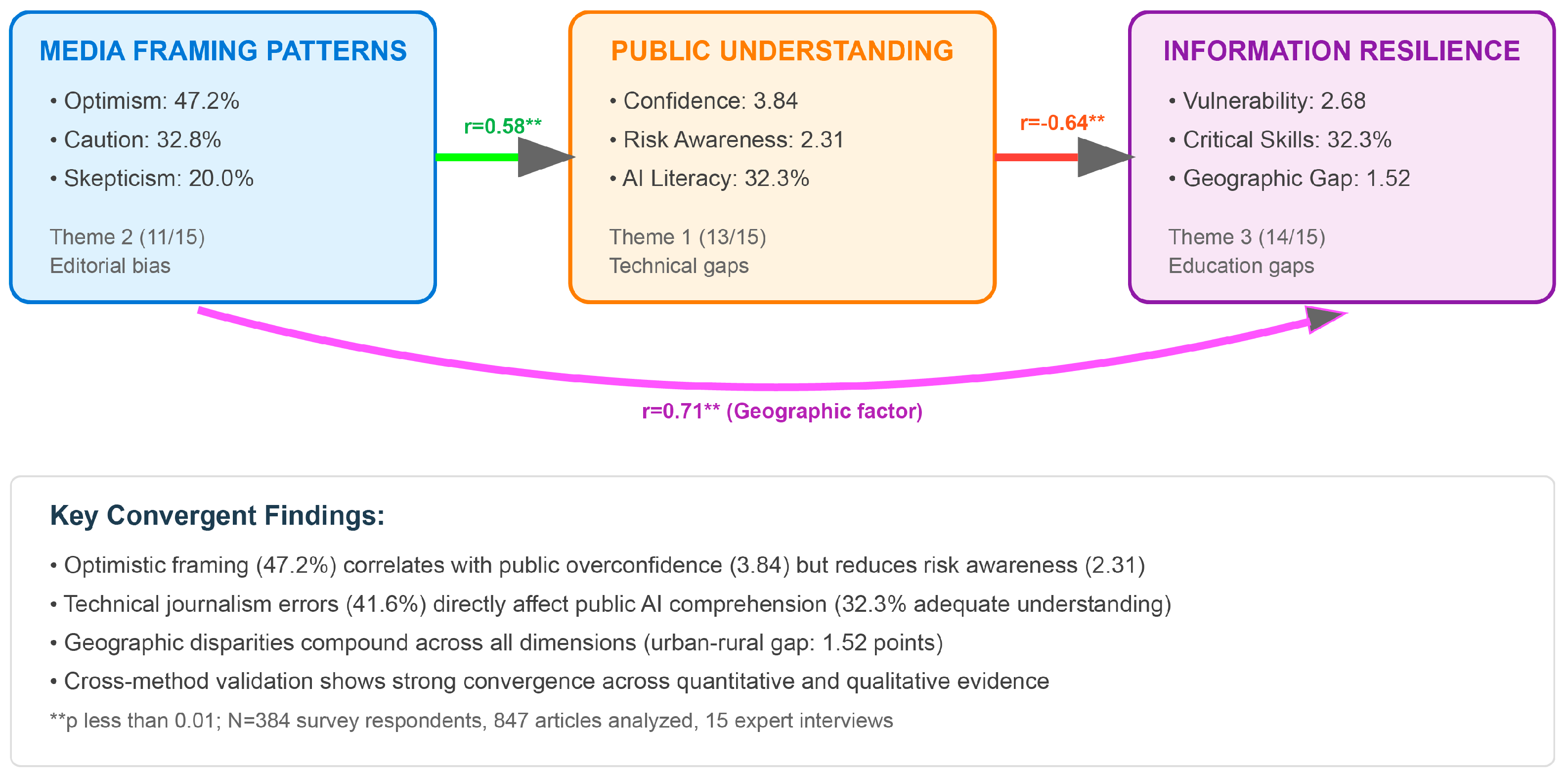

This convergent mixed-methods analysis provides robust evidence for systematic relationships between AI media coverage, digital literacy, and information resilience in Indonesia. Triangulation across content analysis, survey research, and expert interviews validates key findings while revealing nuanced interactions that single-method approaches might miss, as demonstrated throughout

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8 and

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

The research reveals significant challenges and opportunities in the relationship between AI media coverage and digital literacy in Indonesia, aligning with global patterns identified in similar studies (

Newman, 2024;

Helberger, 2019). The predominance of optimistic framing in media coverage (47.2%), combined with moderate digital literacy levels (mean = 2.76) and concerning gaps in AI-specific understanding (32.3% adequate comprehension), creates conditions where Indonesian society may be inadequately prepared for AI-mediated information environments, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

The findings demonstrate that media narratives about AI technologies significantly influence public understanding and attitudes, but current coverage patterns may not optimally serve public education and democratic deliberation needs. The technical inaccuracies found in 41.6% of analyzed articles and the vulnerability profiles identified in

Table 6 suggest that improvements in technology journalism practices and professional development initiatives are urgently needed.

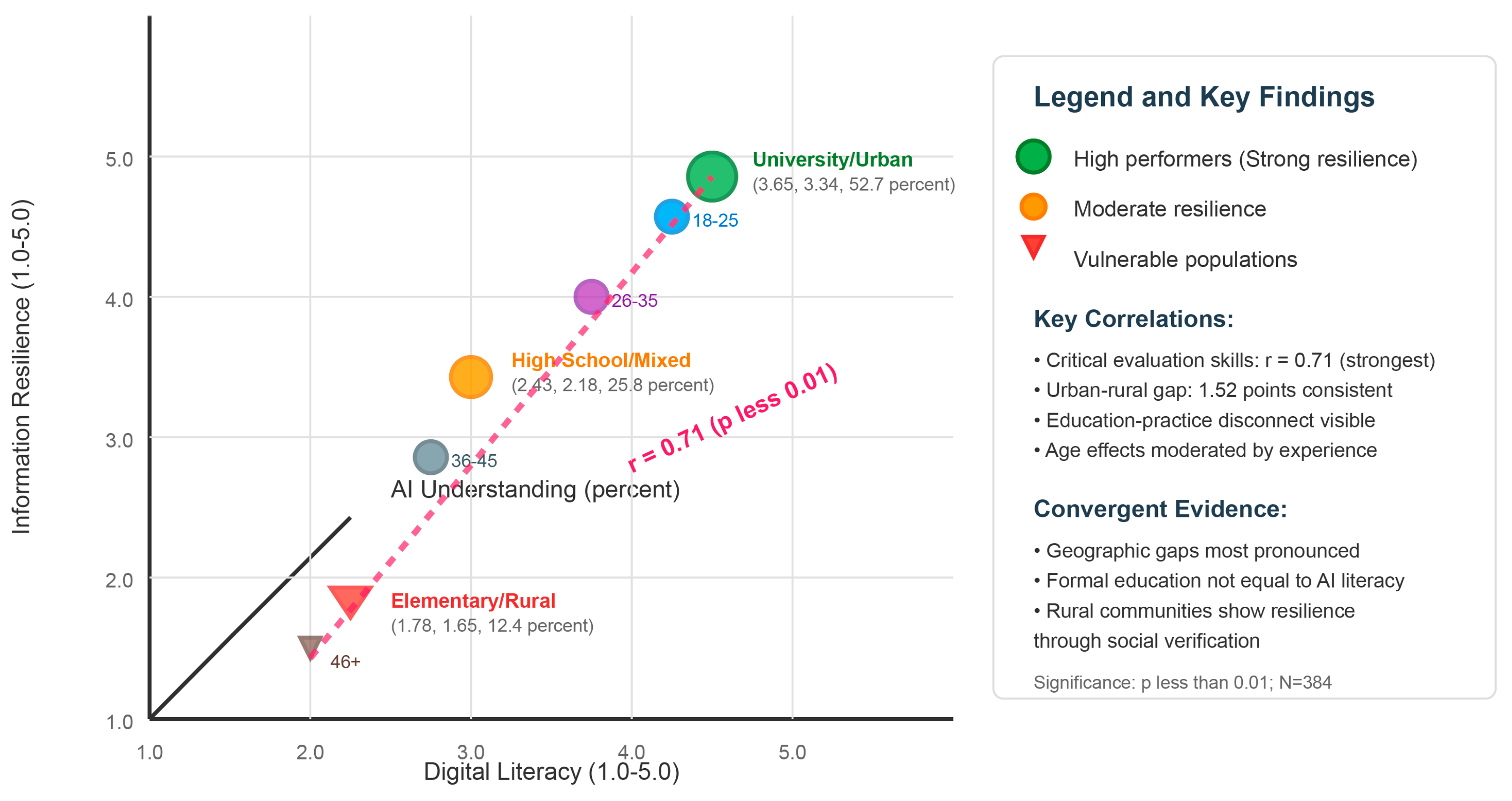

Digital literacy levels among Indonesian internet users show concerning variations across demographic segments, with vulnerabilities among rural populations (mean = 2.18), older adults, and individuals with limited formal education, as detailed in

Table 5. The gaps in AI-specific digital literacy are especially problematic given the increasing prevalence of AI systems in information production and distribution. Cross-method validation confirms that these quantitative patterns reflect deeper systemic challenges in educational preparation and professional capacity, as validated in

Table 7.

Information resilience levels reflect these digital literacy patterns while demonstrating the complex relationships between competency areas and actual information evaluation behaviors, as shown in

Figure 2. The stronger correlation between critical evaluation skills and information resilience (r = 0.71) compared to technical skills (r = 0.42) suggests that educational interventions should prioritize analytical capabilities over purely technical training.

The policy implications of these findings are substantial, pointing to urgent needs for educational reform, journalist training, and regulatory development that can help Indonesian society navigate AI-mediated information environments more effectively.

Table 8 presents a prioritized intervention framework where the success of these interventions will depend on recognition of demographic variations and the need for tailored approaches that build on existing strengths while addressing specific vulnerabilities.

Convergent evidence demonstrates that isolated interventions are likely insufficient given the systemic nature of identified challenges. As shown in the interaction analysis presented in

Table 6, media training without addressing educational gaps may improve coverage quality without enhancing public critical evaluation capabilities. Educational interventions without corresponding improvements in media coverage quality may create more informed audiences for persistently problematic information sources.

As Indonesia continues its digital transformation journey, the relationship between media coverage, digital literacy, and information resilience will remain crucial for maintaining democratic discourse and informed decision-making processes. The challenges identified in this research are significant but not insurmountable, provided that appropriate attention and resources are directed toward addressing them through coordinated efforts across media, educational, and policy sectors.

The implications of this research extend beyond Indonesia to other developing digital economies facing similar challenges in balancing rapid technological adoption with information integrity and democratic participation. The patterns identified in Indonesian media coverage and public digital literacy reflect broader global trends while maintaining important local characteristics that inform context-specific intervention strategies.

The convergent mixed-methods approach validates the value of integrating multiple data sources and analytical perspectives to understand complex socio-technical phenomena, as demonstrated through

Figure 3’s validation framework. This methodological framework provides a replicable model for investigating similar challenges in other contexts while demonstrating how quantitative and qualitative insights can strengthen each other through systematic triangulation.

Future research should focus on longitudinal analysis to understand how these relationships evolve as AI technologies and public understanding develop. Additionally, comparative analysis across multiple Indonesian regions and other Southeast Asian countries would provide valuable insights into how cultural, economic, and political factors influence the dynamics identified in this study.

The fundamental challenge for Indonesian society and others facing similar transformations lies in developing information resilience capabilities that match the pace of technological change while preserving democratic values and social cohesion. Meeting this challenge requires sustained commitment to evidence-based policy development, educational innovation, and media system improvements that serve the public interest in an increasingly complex information landscape.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F.S. and M.M.; methodology, A.F.S.; software, M.A.; validation, A.F.S., M.M. and V.C.C.P.; formal analysis, A.F.S.; investigation, M.M.; resources, M.A.; data curation, A.F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F.S. and V.C.C.P.; writing—review and editing, M.M. and M.A.; visualization, V.C.C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hasanuddin University (EC-284/UNHAS/X/2025; 23 February 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennen, J. S., & Nielsen, R. K. (2018). An industry-led debate: How UK media cover artificial intelligence. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham, D. (2007). Digital media literacies: Rethinking media education in the age of the internet. Research in Comparative and International Education, 2, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Diakopoulos, N. (2019). Automating the news: How algorithms are rewriting the media. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, M., Rickman, A., Vaccaro, K., Aleyasen, A., Vuong, A., Karahalios, K., Hamilton, K., & Sandvig, C. (2015, April 18–23). “I always assumed that I wasn’t really that close to [her]”: Reasoning about invisible algorithms in news feeds. 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 153–162), Seoul, Republic of Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Helberger, N. (2019). On the democratic role of news recommenders. Digital Journalism, 7, 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humprecht, E., Esser, F., & Van Aelst, P. (2020). Resilience to online disinformation: A framework for cross-national comparative research. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25, 493–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juditha, C. (2018). Hoax communication interactivity in social media and anticipation (Interaksi komunikasi hoax di media sosial serta antisipasinya). Journal Pekommas, 3, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnia, N., & Astuti, S. I. (2017). Peta gerakan literasi digital di indonesia: Studi tentang pelaku, ragam kegiatan, kelompok sasaran dan mitra yang dilakukan oleh japelidi. Informasi, 47, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M. (2017). Freedom to hate: Social media, algorithmic enclaves, and the rise of tribal nationalism in Indonesia. Critical Asian Studies, 49, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, J. A., Khan, Q. S., & Varlamis, I. (2021). Fake news detection: A hybrid CNN-RNN based deep learning approach. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 1, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, N. (2024). Journalism, media, and technology trends and predictions 2024. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet, M. C., & Scheufele, D. A. (2009). What’s next for science communication? Promising directions and lingering distractions. American Journal of Botany, 96, 1767–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedemi, T. D. (2012). Digital inequalities and implications for social inequalities: A study of Internet penetration amongst university students in South Africa. Telematics and Informatics, 29, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangrazio, L., & Selwyn, N. (2018). ‘Personal data literacies’: A critical literacies approach to enhancing understandings of personal digital data. New Media & Society, 21, 419–437. [Google Scholar]

- Santika, E. F. (2024). Tingkat penetrasi internet Indonesia capai 79,5% per 2024. Katadata Media Network. Available online: https://databoks.katadata.co.id/teknologi-telekomunikasi/statistik/e6f9d69e252de32/tingkat-penetrasi-internet-indonesia-capai-795-per-2024 (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for business: A skill-building approach. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, K., & Hill, D. T. (2000). Media, culture, and politics in Indonesia. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sonni, A. F., Hafied, H., Irwanto, I., & Latuheru, R. (2024). Digital newsroom transformation: A systematic review of the impact of artificial intelligence on journalistic practices, news narratives, and ethical challenges. Journalism and Media, 5, 1554–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surjatmodjo, D., Unde, A. A., Cangara, H., & Sonni, A. F. (2024). Information pandemic: A critical review of disinformation spread on social media and its implications for state resilience. Social Sciences, 13, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutrisno, E. (2024). Kecerdasan buatan, membangun karakter bangsa di era digital. Indonesia.go.id. Available online: https://indonesia.go.id/kategori/editorial/8678/kecerdasan-buatan-membangun-karakter-bangsa-di-era-digital?lang=1 (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- UNESCO. (2023). Global education monitoring report, 2023: Technology in education: A tool on whose terms? UNISCO. [Google Scholar]

- Vuorikari, R., Kluzer, S., & Punie, Y. (2022). DigComp 2.2, The digital competence framework for citizens. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).