Abstract

Studies on land use and land cover changes are essential for predicting future trends and determining natural resource management decisions and the appropriate and precise detection of land use and land cover change is indispensable for obtaining detailed information. In this study, a purposive sampling technique was used for descriptive purposes. Geospatial approaches are powerful tools for analyzing these changes, offering precise, cost-effective, detailed, and advanced insights. This study focused on understanding the spatiotemporal dynamics of land use, land cover, and its drivers in Melokoza, utilizing Landsat images from 1993, 2013, and 2023, with a resolution of 30 m. Through supervised classification using the maximum likelihood method, this study identified six distinct land uses and land covers: forest, settlement, agriculture, shrubland, bare land, and water bodies. The findings revealed significant transformations, with a dramatic shift from natural forests to agriculture and settlements, which are driven by increasing human demands. Over the past three decades, forest and shrubland cover dropped to 29.89% and 12%, respectively, while settlement and agriculture increased by 154.6% and 231.9%. This transformation underscores the pressing need to address the conversion of formerly forested and shrub-covered areas into vibrant farming and settlement areas. To safeguard the stability and sustainability of our natural resources and ecosystems, stakeholders must focus on the pace of land use and land cover changes, mainly the deforestation linked to agricultural expansion and settlement growth.

1. Introduction

Multifaceted and forceful land use and land cover (LULC) conversion at several scales has ecological and socio-economic consequences [1], impacting the performance of sustainable development goals. Moreover, researchers e.g., [2] have reported that land use and land cover change (LULCC) are among the most significant human-caused global variations affecting the natural environment and ecosystems. These changes are a dynamic and complex practice caused by many interacting processes, ranging from various natural factors to socio-economic conditions [3]. (Regarding the geographical patterns of changes over time, the functions and structures among the multiple alterations to the land covers are intricate [4,5]. Therefore, understanding the scope of LULC change, its driving forces, and their consequences is very crucial for the proper management of land resources [6] and for creating effective strategies for sustainable land management [7,8]. According to [8], knowledge of LULCC also helps to monitor the impact on ecosystems and biodiversity, which is crucial for policymaking. Additionally, knowing the trajectories and extent of land use and land cover changes are essential to generate and provide helpful information to policymakers and development practitioners about the magnitude and trends of land use and land cover changes [9,10].

Environmental changes have a substantial influence on different land features across the landscape [11,12]. Among the most significant and readily apparent markers of changes in ecosystems and livelihood support systems are a change in land use and land cover [13,14]. Such changes are dynamic and non-linear, and they are caused by social, political, economic, and climatic forces operating at local, regional, and global levels [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Since the commencement of agricultural activities, each continent’s land cover has considerably changed [23,24]. In most developing nations, including Ethiopia, these alterations to land use and land cover are influenced by various factors, such as population growth, increased agriculture, settlement, and demand for forest products [25,26]. Furthermore, government policies and markets are fundamental drivers that act at local, regional, and worldwide levels to reinforce or reduce trends in changes to land use and land cover [27,28].

Several studies have reported the impact of land use and land cover changes (LULCC) in various parts of Ethiopia [3,6,8,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. These studies determined that rapid population growth is the leading source of agricultural expansion and settlement, which leads to deforestation and land degradation. Hence, the country has been experiencing significant LULC changes, mainly from the changes in natural resources to the farming system and from human settlement [39,40].

Food security, environmental preservation, and sustainable resource management depend on the comprehension of LULCC, along with their inspection and valuation [31,41,42,43,44]. According to [13,18,45,46], studies on LULCC are essential for forecasting anticipated future trends and making judgments about the planning of managing natural resources. Understanding how land use and land cover are frequently changing, as well as how anthropogenic and natural processes interact, is essential for producing knowledge, managing land resources effectively, and improving decision making [47,48,49,50,51]. Due to this, reliable land use and land cover information are required for better environmental analysis and sound decision making [50,52,53,54,55].

To generate reliable information, a great deal of research has been conducted around the world to monitor land use and land cover change (LULCC) [33,46,56,57]. During the nineteenth century, traditional methods were used to monitor these changes in land use and land cover. However, with technological innovations and user-generated content, researchers can extract meaningful information from satellite imagery more accurately and efficiently [58,59]. Similarly, with the advent of remote sensing and advances in geospatial technology, the monitoring of land use and land cover change has become more cost-effective, time-saving, dependable, and up-to-date [8,58,59,60,61,62,63].

After 1990, several methods and procedures have been used to map land use and land cover, in addition to detecting changes and monitoring [64,65]. Among the methods, remote sensing is a very sophisticated technique that is useful for obtaining timely and accurate information about the status of land use and land cover [66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77]. In addition, satellite images give excellent information regarding land use and land cover, and temporal geospatial data can be used to assess the changes [4,78,79]. The demand for more precise LULCC maps from satellite data is rising, especially when utilizing simple and more user-friendly platforms, like geographical information systems and Google Earth Engine (GIS & GEE) [63,80,81,82]. (Despite being medium-resolution data, many researchers have used Landsat images to track alterations to land use and land cover [43,83,84,85]. It is liked because of its open accessibility and the fact that it has the longest history of worldwide data for earth observation [13]. Using Landsat data, [86] examined a large-scale monitoring program of alterations to the land covers.

To assess and ascertain the current status of resources and to make planning decisions for long-term resource management, LULC dynamics research is becoming an increasingly crucial topic in the investigation of environmental modification [51,65]. Hence, it is essential to define the main factors in the research region and monitor LULC’s changing aspects quickly to develop and monitor future land management systems.

As mentioned earlier, in different parts of the country, a great deal of research has been conducted on land use and land cover changes and their related impacts. The Melokoza district was chosen as a potential research area due to its diverse land use and land cover, which reflect diverse ecological and economic activities. Additionally, the lack of prior studies in this region indicates a gap in knowledge and highlights the need for further exploration. Furthermore, the area is rich in natural resources, providing a unique opportunity to investigate the environmental and socio-economic dynamics that influence land use, land cover, and conservation efforts. Nevertheless, an integrated examination of these aspects concerning LULCC and its pattern of change is lacking in the research area. In light of this, the current study quantified spatiotemporal LULCC and its drivers in the Melokoza district between 1993 and 2023. To achieve this, this study utilized GIS and remote sensing techniques to examine the trends of LULCC in the past, along with the present, magnitude, and driving forces of LULCC in the Melokoza district during the last 30 years. This study examined the recurring satellite images linked to temporal and spatial characteristics of the Melokoza district. Findings from this investigation could contribute to information for decision makers, to land use and land cover planners and managers, and to others involved in sustainable development and natural resource management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Descriptions

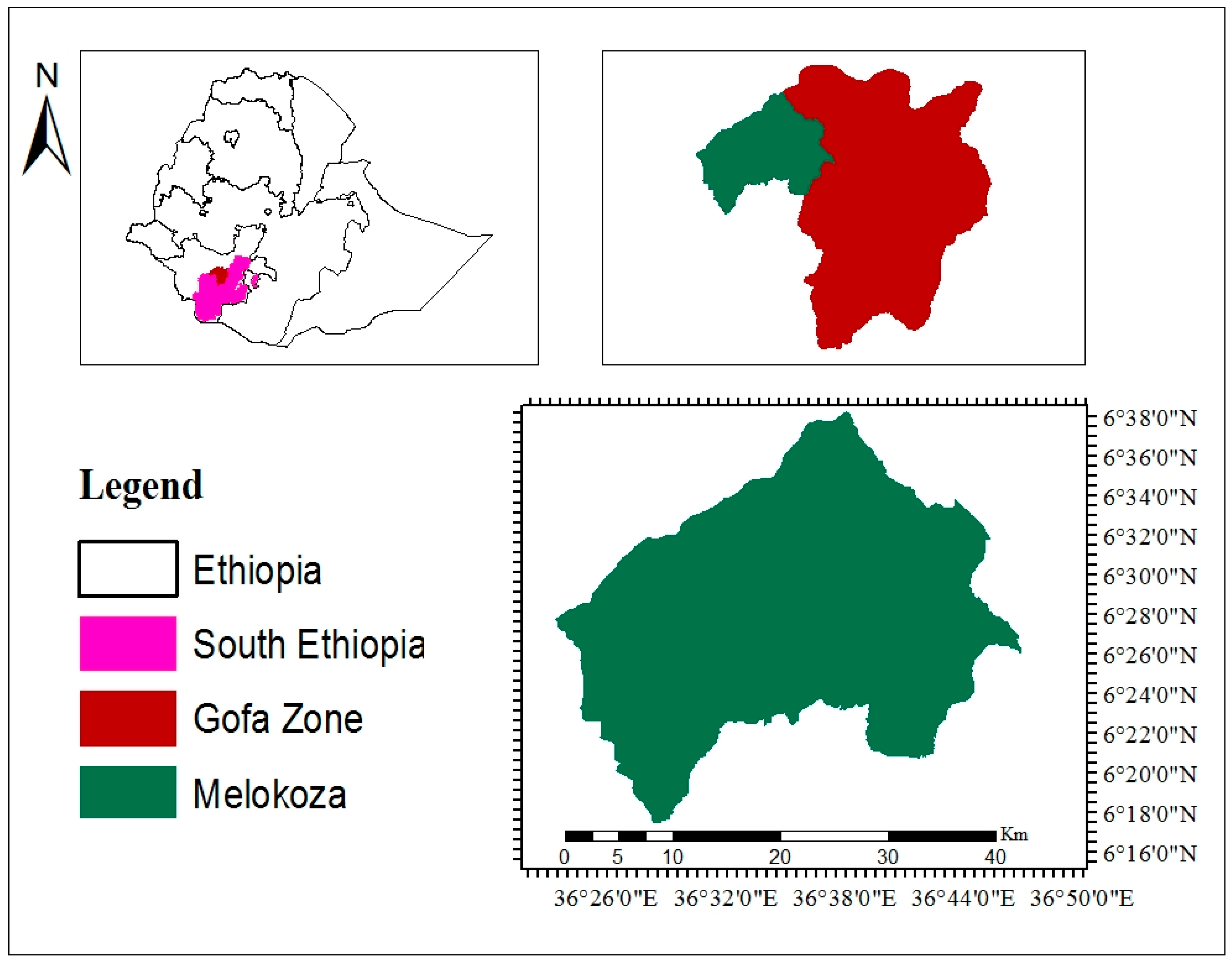

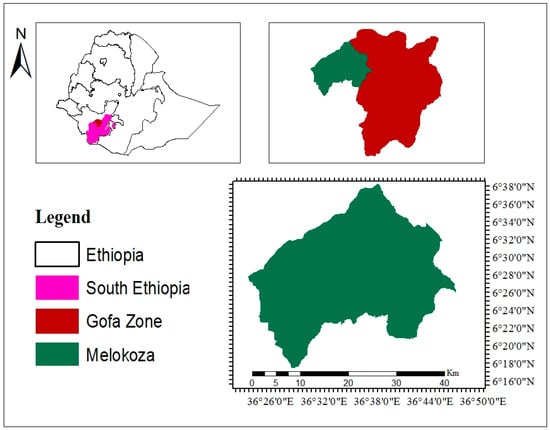

This research was carried out in the Melokoza district, South Ethiopia, Gofa zone, which is situated at 6°16′0″ to 6°38′0″ north latitude and 36°26′0″ to 36°50′0″ east longitude (Figure 1). The elevation varies between 700 and 3200 m.a.s.l. The area experiences bimodal rainfall and receives rain for nine months, with an annual average of 1100–1300 mm. The minimum, maximum, and average recorded temperatures were 15.1 °C, 27.5 °C, and 22 °C, respectively. As stated by the agriculture office of Melokoza, the district is home to 152,502 people, and it has extensive sesame and maize. The overall land coverage of the study area is 168,180.93 ha, of which 31,884.093 ha is covered by perennial crops, 6885 ha by annual crops, 33,687.15 ha by natural forest, and 48,620.78 ha by other land use. In Melokoza, 20.3% of farmers own more than two hectares of land, while 26.7% have a small land property of less than 0.5 hectares.

Figure 1.

A map depicting the research area.

According to the Melokoza Department of Agriculture and Natural Resource Management, the study area’s soil types were classified as clay (15%), loam (50%), and sandy loam (35%). In the higher altitudes, the vegetation consisted of woodland intermingled with highland bamboo and moist forest. The Sirso natural forest possesses the largest area coverage (3501.5 ha) in the study area.

2.2. Sampling Techniques

A purposive sampling technique was employed to carefully select districts, Kebeles, key informant interview (KII) participants, and focus group discussion (FGD) members. This thoughtful approach was guided by significant land use change and valuable land cover resources, like forest patches, as well as by the lack of empirical studies in the area, leading us to the vibrant Melokoza district. To select key informants from the Kebeles Tata, Gaysa, Toba, and Tafa, individuals of >65 years of age with deep-rooted connections to the area were selected, allowing their rich experiences to illuminate the LULCC drivers.

2.2.1. Sample Size Determination

To determine the sample size, Cochran’s formula was used [87]:

where n = sample size for the research; N = total number of households in all Kebeles; e = maximum variability or margin of error 5% (0.05); and 1 = probability of the event occurring.

Therefore, sample size was determined based on the total number of households (i.e., 16,138) from the sampled Kebeles.

2.2.2. Data Sources and Collection

Both primary and secondary datasets were meticulously used to explore the dynamic transformation of land use and land cover (LULC). Primary data emerged through the thoughtful design of semi-structured questionnaires, insightful key informant interviews (KIIs), focus group discussions (FGDs), and field observations. In-depth interviews with key informants, Kebele leaders, government officials, and experts were sought to unearth profound insights into the drivers of LULCC. Furthermore, FGDs served to validate and enrich the data, fostering meaningful dialogue within small, purposefully selected groups of participants. Field observations offered a vital lens into the reality of LULC practices. Simultaneously, a wealth of secondary data complemented the primary findings, with multi-temporal satellite images and ancillary data skillfully processed using ArcGIS10.3. Ground control points (GCPs), along with digitized and topographic maps, were instrumental in the precise geo-referencing of satellite images, weaving together a tapestry of knowledge and understanding.

In this study, LULC time series data were generated from multispectral Landsat satellite images, such as Multispectral Scanner (MSS), Thematic Mapper (TM), Enhanced Thematic Mapper (ETM+), and Operational Land Imagers (OLI), which were acquired and processed from the three separate years of 1993, 2013, and 2023 (Table 1). Landsat datasets were preprocessed with GIS software by applying basic image preprocessing techniques of editing, restoration, enhancement, image classifications, and image accuracy assessments. To facilitate the supervised classification, ground control points were collected for each land use as classification training locations and the ability to separate spatial signatures. The classification signature for each land use and land cover type was maintained within acceptable ranges and across land use cover types. A maximum likelihood classification algorithm was used to classify the images. Ground control points were also collected using GPS devices to assess classification accuracy for each land use type for the year 2023. In each type of imagery used, we only used a range of bands from red, green, blue, and near-infrared to determine the vegetation from other land uses.

Table 1.

Explanation of data types and sources.

2.2.3. Field Observation and Ground Control Point (GCP) Data Collection

Field observation captures real-time events and their contexts. This approach provides a profound understanding of the phenomena we studied [88]. In this spirit, field visits were conducted to immerse ourselves in the study area, enhancing our visual interpretation of the images and selecting reference points vital for training areas in supervised classification, alongside collecting ground control points (GCPs). During our fieldwork, 480 ground control points were collected across six distinct land use and land cover classes through random sampling techniques with a handheld GPS receiver. These invaluable reference data empower us to verify various land cover types and to assess accuracy, underscoring the significance of our journey in understanding the landscape.

2.2.4. Socio-Economic Data Collection

In this study, we harnessed the power of household questionnaire surveys, focus group discussions (FGD), and key informant interviews (KII) to unveil the driving forces behind land use and land cover (LULC) change in our vibrant study area. A thoughtful selection process led to the involvement of 390 households across four distinct Kebeles, with sample sizes determined by a careful calculation of household proportions. From the rich tapestry of our community, 73 respondents from Tata Kebele (70 male and 3 female), 129 from Toba Kebele (124 male and 5 female), 122 from Dhafa (120 male and 2 female), and 66 from Gaysa (62 male and 4 female) shared their invaluable insights. This method ensured that our sample truly reflected the diverse voices within the broader region. The survey questions were crafted in both close-ended and open-ended formats, which were designed to extract essential information about the dynamic LULC changes and their underlying drivers. Additionally, we engaged with 20 key informants (5 from each Kebele) and facilitated 8 enriching focus group discussions (2 individuals from each selected Kebele), all contributing to a deeper understanding of our shared environment.

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Land Cover Classification

Land capabilities, the susceptibility of current land use to specific management techniques, and the feasibility of various activities were thoroughly assessed to determine the appropriate types and quantities of land use and land cover classifications. A comprehensive preliminary field survey was conducted in the area, which was supplemented by Google Earth imagery to address inaccessible regions. During this survey, valuable insights were gathered from local elders regarding land use and land cover conditions and their driving factors. This study identified and analyzed six distinct LULC categories using satellite imagery: forest, settlement, agriculture, shrubland, bare land, and water body. The classification results for 2023 were meticulously analyzed and evaluated through an accuracy assessment technique to ensure they accurately reflected on-ground realities. This classification served as the foundation for the LULC class map. The approach included an unsupervised classification to gain insights into the overall classes and to identify suitable training sites. The outcomes from this unsupervised process were instrumental in selecting training locations for the subsequent supervised classification analysis. The image was then classified at the pixel level using the maximum likelihood classifier approach during the supervised classification phase.

2.3.2. Accuracy Assessment

At the end of land use and land cover classification, it is essential to document the categorical accuracy of the classification results. Classification is not finished until its correctness has been evaluated. One common technique for demonstrating classification accuracy has been achieved is by creating a classification error matrix. Error matrices compare the association among the related outcomes of automated classification and known reference data, or ground truth, category by category. Therefore, a confusion matrix was applied to determine whether the classification results were accurate by taking representative points from each kind of land use and land cover [89]. In this study, an accuracy assessment of the classification result was created based on the 2023 land use and land cover image classification using GIS software. The accuracy of the producer, user, overall, and kappa coefficient were calculated to determine how well the classified image resembled the actual characteristics on the ground. To effectively evaluate the results, the following accuracy assessment formula was applied:

where Obs = observed correct, which represents the accuracy reported in the error matrix (overall accuracy); and Exp = expected correct, which represents correct classification.

2.3.3. Post Image Classification and Change Detection

Pixel-based statistical analysis was applied to make a post-classification comparison for the three separate images. In light of this, three comparisons were conducted using three classified maps from 1993, 2013, and 2023. These comparisons were between maps from 1993 and 2013, maps from 2013 and 2023, and maps from 1993 and 2023. The following formula was used to analyze the change rate for each type regarding land use and land cover:

where A = recent areas of land use and land cover in ha, B = previous area of land use and land cover in ha, and C = time interval among A and B in years.

2.3.4. The NDVI or Normalized Difference Vegetation Index

A normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) was analyzed to determine the health coverage of the vegetation in the study area. According to the NDVI principle, values must always fall between −1 and +1. For example, if you have a negative value, it is almost certainly water. However, if your NDVI rating is close to +1, you likely have dense green leaves. However, when NDVI readings are near zero, there are no green leaves, and the area may be urbanized. Values near zero (−0.1 to 0.1) are typically associated with barren landscapes of rock, sand, or snow. Shrub and grassland are represented by low positive values (about 0.2 to 0.4), whereas temperate and tropical rain forests are indicated by high values (values approaching 1) [90]. The slope of the line was used to deduce the direction of the vegetation variation (either decreasing or increasing) and the strength of the variation from the trend line’s steepness (such as, for example, no change, minimal change, moderate change, or severe change). To calculate the NDVI, band 3 (Red) and band 4 (Near Infrared) signified Landsat 7, whereas band 4 (Red) and band 5 (Near Infrared) signified Landsat 8. The NDVI was calculated using the following formula:

where IR is the reflectance value of the infra-red band (Band 4 and 5), and R is the reflectance value of the red band (3, 4):

Landsat 4–5 TM = (B04 − B03)/(B04 + B03)

Landsat 7 ETM+ NDVI = (B04 − B03)/(B04 + B03)

Landsat 8 NDVI = (B05 − B04)/(B05 + B04) [91].

In this research, the NDVI values were used to determine the vegetation health or coverage (Table 2).

Table 2.

The reference NDVI values for the different land uses.

2.3.5. Socio-Economic Data Analysis

In this study, our primary focus in integrating socio-economic data with quantitative remote sensing data was to draw invaluable insights from the local community, enriching our understanding of the study’s results. We meticulously analyzed the collected data using both quantitative and qualitative techniques. The qualitative data analysis involved a thorough identification, examination, and interpretation of the patterns and themes within the textual data, revealing how these elements addressed our research questions [93]. Descriptive statistics were used to explore the qualitative data from FGDs and key informant interviews, frequencies, and percentages. Simultaneously, the quantitative data from the household survey were analyzed using Microsoft Excel, and these were then presented through frequencies, percentages, and tables, illuminating the findings in an impactful manner.

3. Results

3.1. Land Use and Land Cover

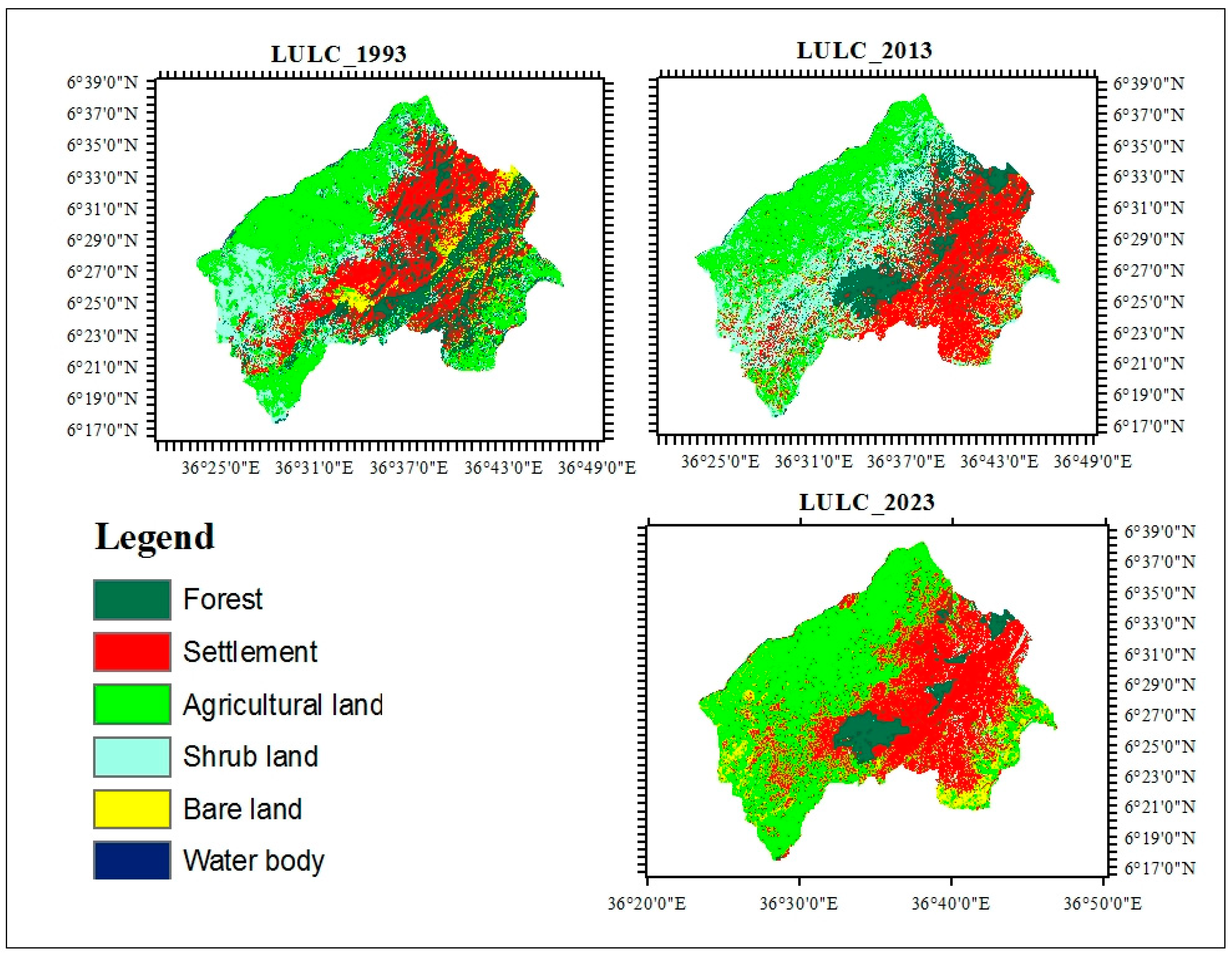

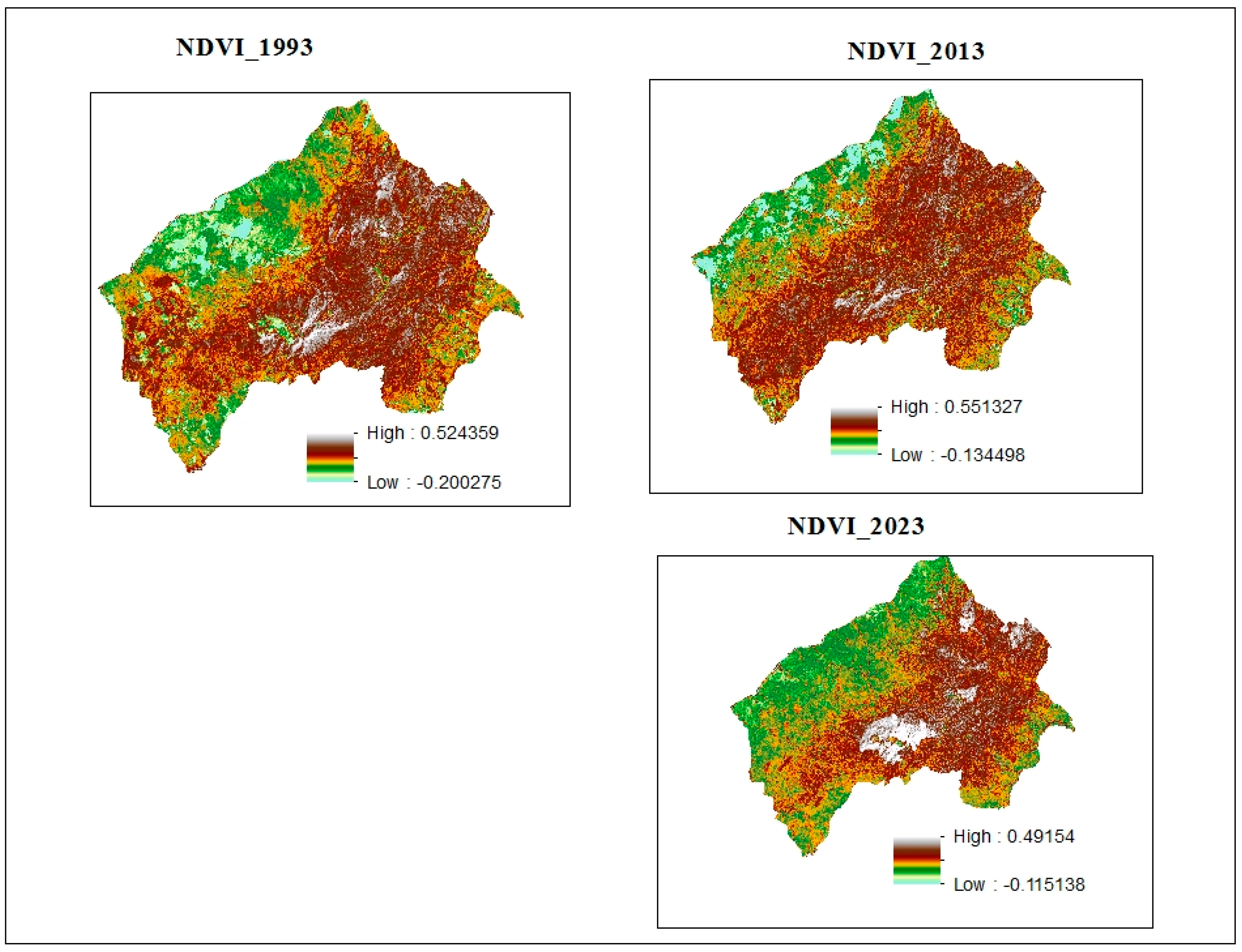

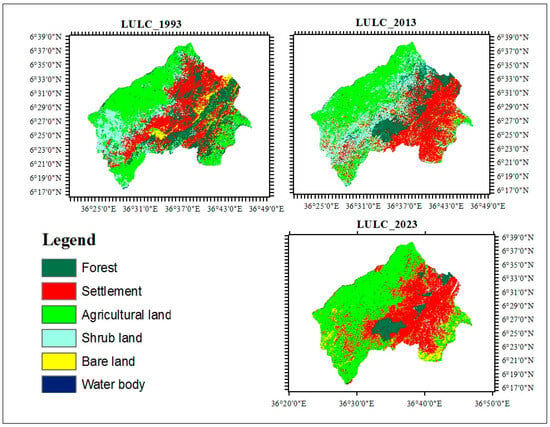

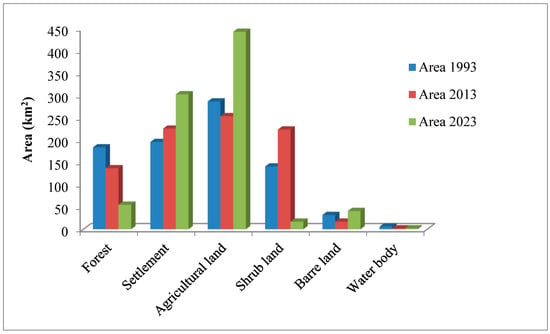

The findings of the LULCC from 1993 to 2023 are summarized in Figure 2. Overall, the six land use and land cover classes were distinguished in the study area and assigned a proportionate coverage area.

Figure 2.

LULCC for the three time periods (1993–2023) of the Melokoza district.

Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 provide a summary of the LULCC trend from 1993 to 2023 based on six classes and given a comparable amount of covered area.

Table 3.

The land use and land cover change (km2) between the years 1993 and 2013. The reference year was 1993 and the change recorded was for 2013.

Table 4.

The land use and land cover change (km2) between the years of 2013 and 2023. The reference year was 2013 and the change recorded was for 2023.

Table 5.

The land use and land cover change (km2) between the years of 1993 and 2023. The reference year was 1993 and the change recorded was for 2023.

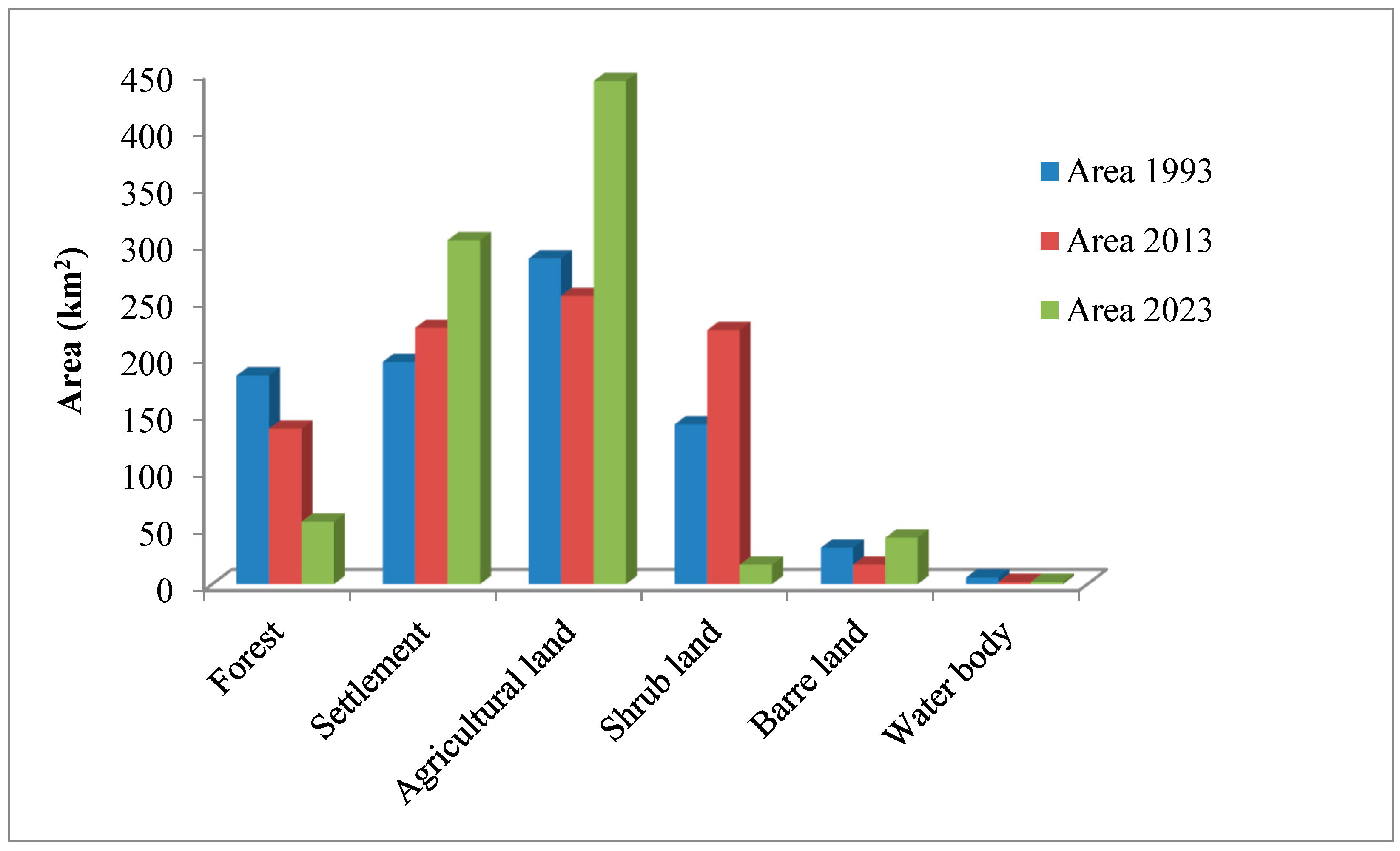

The main types of land use and land cover during the research period from 1993, 2013, and 2023 are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The LULCC areas between the three time periods.

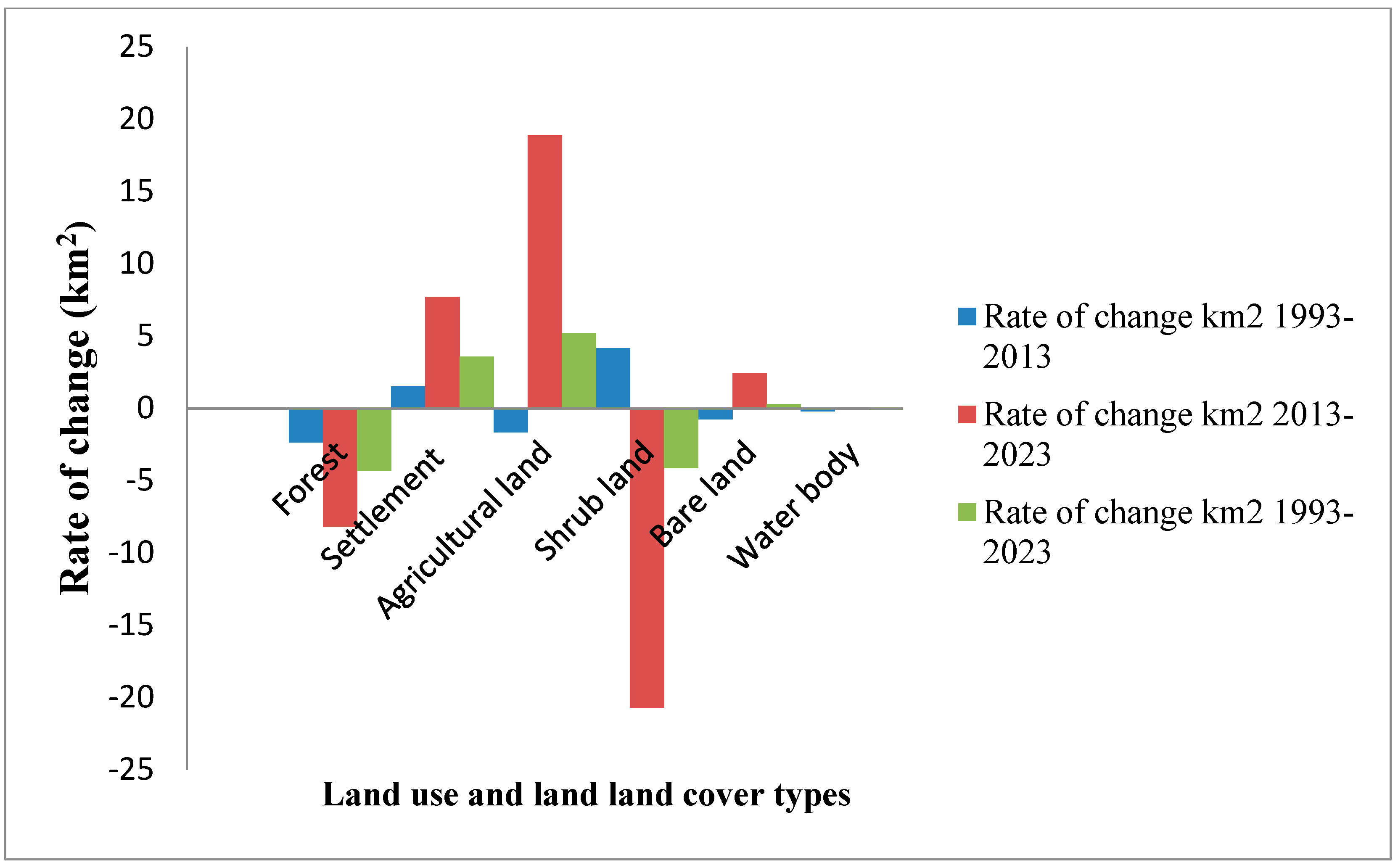

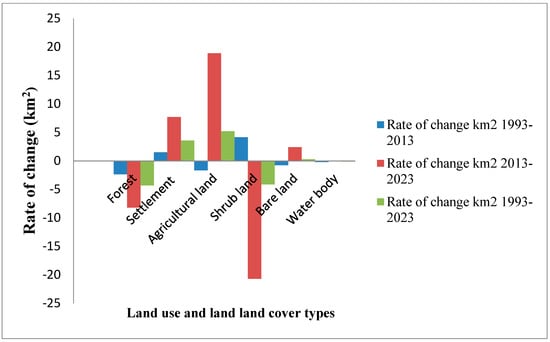

The changes in the rate of the LULC classes are clearly illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The rate of change in land use and land cover throughout the span of the study period.

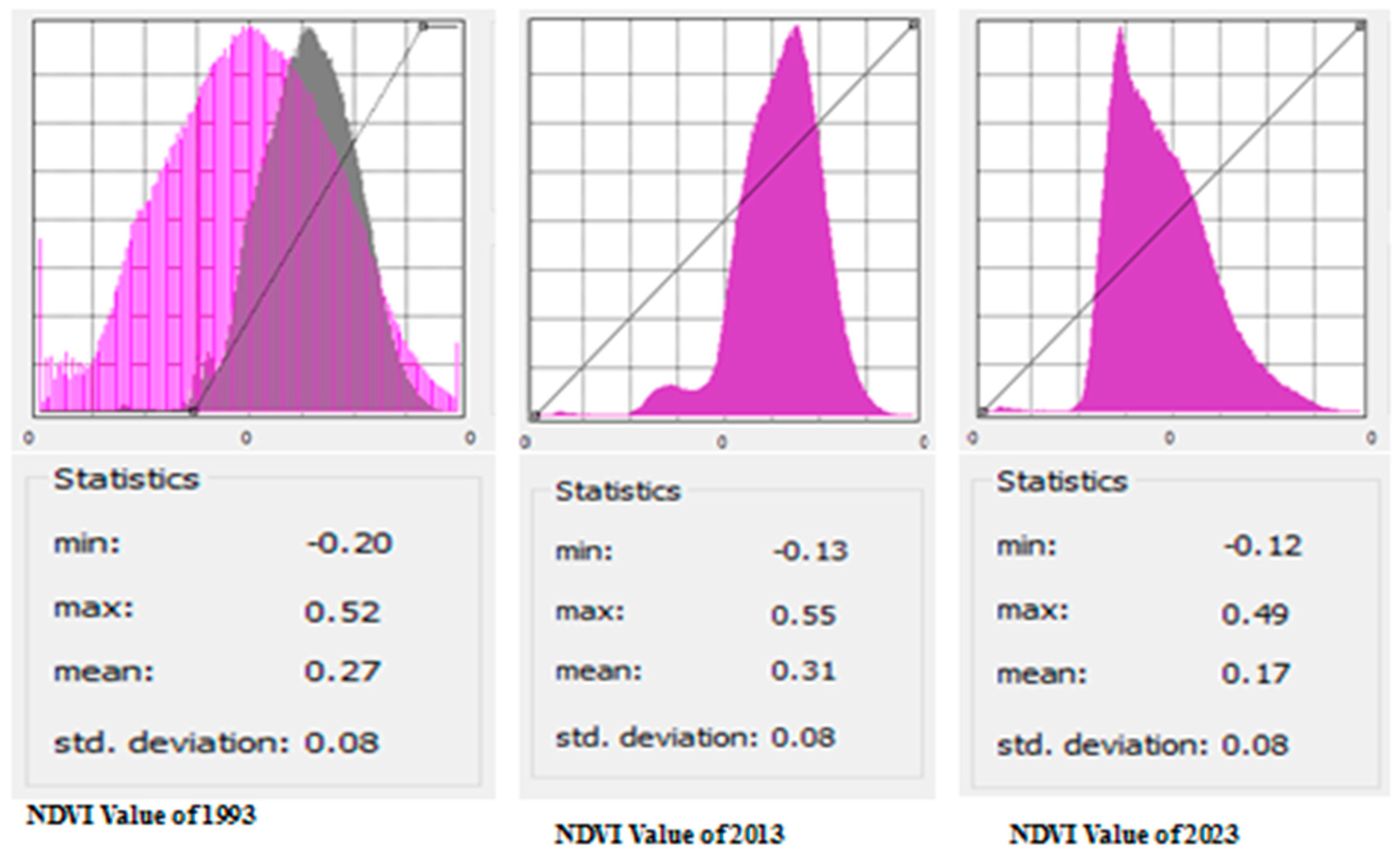

3.2. Detecting NDVI Changes and Forest Health

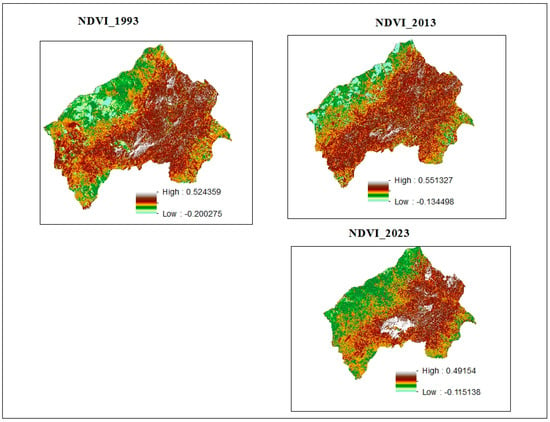

Figure 5 shows the NDVI values of 1993, 2013, and 2023 within the study area.

Figure 5.

NDVI changes for the years 1993–2023.

3.3. The Results of Accuracy Assessment

The findings from the accuracy assessment are concisely outlined in Table 6, which summarizes the results in detail.

Table 6.

The overall accuracy, producer accuracy, user accuracy, and kappa (Khat) coefficient values.

3.4. Drivers of LULC Changes

The results of the household questionnaire survey determined seven major driving forces of LULCC were summarized in Table 7. Among these drivers, agricultural expansion and settlement expansion represent the most significant percentages, showcasing the dynamic evolution of the study area.

Table 7.

The major drivers of LULC changes in the study area.

4. Discussion

In this study, the LULCC time series data were generated from multispectral Landsat satellite images, revealing the dynamic changes in our landscape. Utilizing GIS software, we meticulously processed Landsat datasets through essential techniques, such as editing, reinstatement, enhancement, image classification, and accuracy assessment. These methods enabled us to categorize and identify the diverse land use and land cover types throughout the study. Ultimately, this study discovered six distinct land use and land cover classes. These classified land use and land cover classes confirmed that there were conversions of land use and land cover from one type of land classes to another. Remarkably, agricultural land and settlement emerged as the predominant classifications, highlighting the evolving relationship between humanity and the earth. The largest land cover type in 1993 was agricultural land. Moreover, trends of decreasing and increasing were noted for all LULCs in 1993, 2013, and 2023.

In 2023, the study area’s central region was covered by forest patches, with a few patches on the northern side. Mainly, agriculture was clustered in the west, and settlements were widely dispersed throughout the study area from the east to the middle, with a smaller number throughout the southern and other parts (Figure 2). Farmers have noted that soil fertility, good weather patterns, and the accessibility of the Omo River for irrigation are the fundamental causes of agriculture’s dominance in the western part. The greater portion of the water body was found in the Omo River basin, where the Koysha hydroelectric project was located.

Similarly, as shown in Figure 2, the elderly people living in the study area confirmed that settlement was mainly noticed in the middle of the year of 1993. This was likely due to the area’s appropriate topography in addition to an unlawful land capture technique that involved clearing the forest for settlement. The vast amounts of settlement and agricultural lands were later shifted to shrub after the local authorities forced the illegal settlers to leave the forest region and its vicinity later in 2013. Since urbanization is increasing, according to the elders, many rural dwellers prefer to reside in the eastern part. Also, there was an overall shift in settlement from the center to the east between 1993 and 2013 (Figure 2). Additionally, between 2013 and 2023, settlements in the south and southeast shifted to bare land. These were related to the construction of highways and dams, such as, for instance, the Great Koysha hydroelectric dam that is being built in the south and the Sawula to Melokoza highway in the southeast. The removal of certain materials from the ground and natural landslides were the reason why the south and southeast shifted to bare land (Figure 2).

Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 provide a summary of the LULCC trend from 1993 to 2023 based on six classes and given a comparable amount of covered area. The classification of land cover according to the six land use and land cover types identified throughout the three occasions shows the conversion of the different land use classes. The main land uses that gradually increased throughout the study session were agriculture and settlements. For example, agricultural land increased by 88.50% from 1993 to 2013, 174.41% from 2013 to 2023, and 154.36% from 1993 to 2023. Bare land increased at a significant rate due to the Koysha hydroelectric power dam and highway constructions that might fragment the forest and thus make bare land. Forest-covered lands were mainly converted into agriculture and settlement. The largest change in forest cover to other land use types recorded between 1993 and 2013 was forest to agriculture, followed by forest to settlement. Similarly, between 2013 and 2023, more forest-covered lands were converted to agriculture, followed by settlements. In the area, conversions of shrubland, forest, bare land, water bodies, and agricultural land to settlement were mainly related to the increment of urbanization and human population growth.

As depicted in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 and Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, agricultural land and settlement increased throughout the study sessions at the expense of other land use and land cover classes. Across the country and worldwide, similar findings have been reported. The present research results are in line with the studies conducted in Brazil, Africa, Central Asia, Eastern China, and Southeast Asia. For example, the increasing desire for food goods and households has led to an expansion of agriculture and settlement [94]. The greatest net agricultural expansion, according to [95], was observed in Africa, with South America and Asia following. As a rising need for food is driving agricultural development in historically less developed savannas and woodlands, this expansion is representative of Sub-Saharan Africa in general and East Africa in particular [96].

Furthermore, LULCC research conducted in Ethiopia has shown that agriculture and settlement have grown at the expense of forests and shrublands [26,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104]. For example, the research by [97] in the Andassa watershed revealed that, between 1985 and 2015, the percentage of farmland increased from 62.7 to 76.8%, which destroyed forests and biological resources related to the increased population growth.

A comparable effect of the agricultural development on LULCCs in the Gambella region has also been documented [105]. Similarly, ref. [106] reported that agricultural growth accounts for 73% of all deforestation in emerging nations. According to [107,108,109], the development of agricultural land to meet the communities’ food needs has had a notable effect on other land uses.

Conferring to the past studies done in Ethiopia, the increase in population number is the primary driver for LULC modification [88,110,111,112]. These results holds true for the present conditions of population increase in the study area; for example, according to the 1994 national census, the Melokoza district had a total population of 74,992, with 37,349 males and 37,573 females. By contrast, the 2007 Census conducted by the Central Statistical Agency (CSA) showed significant growth in the district’s population, reaching 120,398. This increase included 59,877 men and 60,521 women, highlighting the demographic changes within a relatively short period. Population growth is one of the primary driving forces behind land use and land cover change (LULCC) in the study area. The result in (Table 7) indicates that 30% and 25% of respondents identified high expansion of agriculture and settlement as the main underlying drivers of LULC change. This study showed that forests gave way to agricultural land and subsequently to settlement, as verified by the rapid annual increment rate in agriculture and settlement, as well as by the small reduction rate in an area covered with shrubs and forests. This trend indicates that land previously covered by forest, shrubland, and grassland is increasingly being converted into farmland and settlement. As the population continues to rise, so too does the demand for land for crop production and wood products necessary for energy and construction. This study aligns with previous research in Ethiopia, which has consistently identified agriculture, settlement, and population growth as the key factor driving LULC change [44,88,110,113,114,115]. (Likewise, according to [115,116], there is a growing demand for agriculture because of the swift increase in population.

Like the findings of the current study, a notable decrease in forest cover has been reported across different regions of Ethiopia, such as, for example, by [117] on the Senbat watershed between 1957 and 1980. This deforestation or decrease in forest and shrubland covers was mainly caused by an increase in agriculture, settlement, and animal production. Similarly, a study conducted along the Lake Basaka basin by [118] showed that the amount of forest cover decreased from 42.2% in the early 1960s to scarcely 6% in 2008. Results from this investigation and others serve as markers or evidence for Ethiopia’s widespread deforestation. Also, [119] claimed that, during the Derge era, a sizable percentage of the forest resources were transformed into different land uses, such as agriculture and settlement. Similarly, it has been explained by other authors e.g., [99,107,113] that these alterations of land use and land cover may be permitted by institutional enforcement and a lack of clearly defined policies.

Policy and institutional factors play a pivotal role in shaping our environment. The household survey results (Table 7) reveal that 7.5% of respondents believe the absence of strong policies and effective institutional frameworks is a significant underlying cause of the LULC changes in the Melokoza district. Focus group discussions and key informant interviews underscore this notion, highlighting the challenges posed by weak law enforcement and poorly defined policies. These issues lead to mismanagement, illegal settlements, and misuse of precious natural resources. The presence of illegal settlers, tree-cutting, and charcoal producers underscores the urgent need for better management of LULCC. Historical perspectives, such as the findings by [120], emphasize that extensive forest resources have drastically transformed during the Derge regime. Similarly, studies by [99,107,113] reinforce the idea that well-defined policies and robust institutional enforcement are essential to preserve our land and ensure a sustainable future. The household survey results (Table 7) reveal that fuelwood collection and charcoal production are pivotal factors in the landscape change within the study area. Remarkably, 10% of respondents identified these activities as key drivers of land use and land cover change (LULCC) in the study area. It is inspiring to note that approximately 99.5% of respondents rely on fuelwood as their primary energy source for cooking. In Ethiopia, wood serves not only as the main energy source, but also as a vital construction material for both rural and urban communities. This study aligns with the findings of [121,122], highlighting that tree cutting for domestic and commercial purposes remains a significant force behind the forest degradation that leads to LULCC. The abovementioned factors are also an observable fact confirmed by the present study.

Various researchers e.g., [31,117,118,123,124,125] have reported that growing population and urbanization are causing a swift conversion of forested areas into agricultural land and settlements in Ethiopia. The findings of the current study imply declining rates of forest and shrub lands and increasing rates of agricultural land and settlement. The abovementioned studies broadly demonstrated to what extent agriculture and settlement expanded into forest cover throughout the study periods. Thus, the depletion of natural resources has led to a degradation of the ecosystem of the entire landscape. Population growth is among the major reasons contributing to LULCC in Ethiopia [120].). Based on the findings of the present study, the same holds true in the study area. The idea proposed by [4] also confirms the outcomes of this investigation.

This scenario has caused a swift deterioration of natural resources, with the most affected being forest resources, soil layers that have already experienced erosion, ongoing loss of nutrients, and landslides. A study by [126] indicate that, in Ethiopia, urgent action is required to address the issue of land use and land cover and land degradation by applying appropriate technology to enhance forest resources management and sustainable agricultural production. This recommendation also applies to the Melokoza districts.

Throughout the investigation, variations were found in the yearly percentage of alterations to the land use and land cover. Likewise, from various areas in the country, similar findings have been reported [102,127] that LULC change is intricate and interconnected since it involves the growth of a single type of land use at the overhead of another. According to the household survey in (Table 7), 5% of the respondents believed that, in the study area, the great Koysha hydroelectric dam construction caused a decrease in the shrubland and forest cover and an increase in bare land. The construction of an artificial dam has an influence on the cover of other land use and land cover classes, such as forestlands, shrublands, and grasslands [128,129]. According to the local elders, in 2013, the government evicted the illegal settlers from in and around the forests. Due to this, shrublands were changed to forest and agricultural lands were converted to shrublands. The same result was also reported from different areas [117,121].

In general, the current investigation clearly shows that, overall, rising agricultural and settlement expansion has resulted in a decline of forest and shrubland expanses, which has caused the landscape to become more fragmented. Numerous prior studies conducted in various regions of Ethiopia by different authors e.g., [15,20,121,130,131], as well as studies from numerous tropical countries [132,133], have provided evidence of this. Therefore, nations and nationalities at local, regional, and large global scales should pay attention to the land use and land cover change leading to natural resource degradation and global climate change.

Figure 5 depicts the large dark and light brown colors of the forest region, indicating the drop in forest covers. Hence, the highest and lowest NDVI values of the study periods from 1993–2023 were 0.52 and −0.20, 0.55 and −0.13, and 0.49 and −0.12, respectively. Meanwhile, the NDVI values of 1993, 2013, and 2023 were 0.52, 0.55, and 0.49, respectively, which are acceptable ranges for sparse and dense vegetation. These imply that greenness or vegetation cover was elevated in the research period between 1993 and 2013 and decreased between 2013 and 2023. The increase in the NDVI for the urban area, settlement, and water bodies in green can be disregarded because the NDVI is only useful for monitoring vegetation. It is evident that, throughout the thirty years, nearly the whole forest had an NDVI decline.

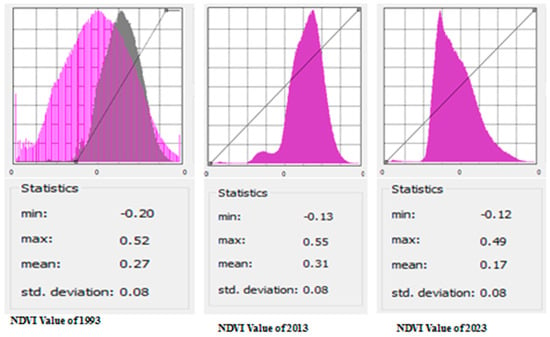

Figure 6 displays the comparison between the NDVI statistics for the years 1993–2023. The NDVI values for 1993, 2013, and 2023 were −0.20, 0.52, 0.27, and 0.08; −0.13, 0.55, 0.31, and 0.08; and −0.12, 0.49, 0.17, and 0.08, respectively, for the min, max, mean, and standard deviation. The year 2013 showed an escalation in the max and mean values (0.55 and 0.31), whereas the year 2023 showed a decrease in the max and mean values (0.49 and 0.17). The statistical data differences between study sessions revealed an increase from 1993 to 2013 and a decline in 2023 of the max and mean values, respectively. Also, this implies the decline of vegetation healthy coverage.

Figure 6.

Histogram of the maximum and minimum NDVI values.

Between 1993 and 2013, the mean NDVI score showed that the healthiness of the forests was enhanced, but this then decreased in 2023. An increase in NDVI values determines the increase in the health of vegetation covers, whereas a decrease in NDVI values determines the decline in the vegetation health cover of an area. NDVI values imply the decline scenario of the vegetation cover in the study area. Similar findings have been reported by studies conducted elsewhere [90,133].

The classification was carried out with overall accuracies, showcasing the potential of our approach (Table 6). The results revealed that the user accuracy for individual classes ranged from an impressive 80% to a perfect 100%, while the producer accuracy varied between 87.5% and 100%. Although lower producer accuracy was observed for bare land at 87.5%, this highlights the challenges faced in identifying the grassland and bare land during the drought season and its low ground cover condition [118]. The resulting LULC map achieved an admirable Kappa (k) of 0.89, reflecting a strong alignment between the reference data and the remotely sensed classification [134]. With a Kappa statistic exceeding 80%, a remarkable agreement was witnessed [135]. Thus, the present study’s Kappa statistic of 89% stands as a testament to the strength of our findings.

5. Conclusions

To better understand the past and contemporary land use and land cover, this study examined the periodic satellite images associated with the geographical and temporal elements of the Melokoza district. In light of this, this study’s core purpose was to analyze the spatiotemporal LULCC progress in the study area from the years of 1993 to 2023. This study used Landsat images (4–5 and 8) and GIS and remote sensing tools to investigate the past and present trends of LULCC. Six land use and land cover classes were identified using supervised classification approaches. The research area has exhibited dynamic alterations in land use and land cover over spatiotemporal and geographical scales from 1993 to 2023. This change has ensured that forestland classes are at the forefront of the conversion to two main land uses, such as agriculture and settlement, due to economic and demographic changes. Also, the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) values showed declined trends throughout the study years. The factors mentioned above imply the decline in vegetation health in the study area. The lack of strong institutional and technological support is the primary influence of LULCC changes in the Melokoza district. The viability of agriculture, settlement, and the related obtainability of natural resources in the study area may be seriously jeopardized if this state is permitted to proceed with this trend. Thus, natural resource managers, environmental specialists, and other stakeholders should play a key role in raising public awareness regarding LULCCs and promoting the long-term conservation of natural resources, particularly forestland, through the implementation of a green legacy program in the research area to mitigate local, regional, and global climate changes.

Author Contributions

A.C.: planning, writing, processing, collecting the data, analyzing the data, and writing the manuscript; S.S.: Led the conceptualization and design of the research; contributed extensively to the formulation of the research objectives and methodology. Took primary responsibility for drafting, reviewing, and critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content. Provided ongoing supervision throughout all phases of the study, including data interpretation and quality assurance. Played a central role in integrating interdisciplinary insights and ensuring the overall coherence and scholarly integrity of the work; T.G.: supervision, conceptualization, and data collecting; A.U.: supervision, reviewing, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no grants for this particular work.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support this study are included in the manuscript and are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Arba Minch University for their financial assistance. Our thanks also go to the respondents for sharing the imperative data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Molla, M.B. Land use/land cover dynamics in the central Rift Valley region of Ethiopia: The case of Arsi Negele district. Acad. J. Environ. Sci. 2014, 2, 74–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Raza, A.; Syed, N.R.; Acharki, S.; Ray, R.L.; Hussain, S.; Dehghanisanij, H.; Zubair Elbeltagi, M.A. Land Use/Land Cover Change Detection and NDVI Estimation in Pakistan’s Southern Punjab Province. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesuph, A.Y.; Dagnew, A.B. Land uz`se/cover spatiotemporal dynamics, driving forces and implications at the Beshillo catchment of the Blue Nile Basin, North Eastern Highlands of Ethiopia. Env. Syst Res. 2019, 8, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Geist, H.J.; Lepers, E. Changes in land usage and land covers in tropical regions. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2003, 28, 205–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Guo, Z.; Askar, A.; Li, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, H.; Saria, A.E. Dynamic land cover and ecosystem service changes in global coastal deltas under future climate scenarios. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2024, 258, 107384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bufebo, B.; Elias, E. Land Use/Land Cover Change and Its Driving Forces in Shenkolla Watershed, South Central Ethiopia. Sci. World J. 2021, 2021, 9470918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briassoulis, H. Analysis of Land Use Change: Theoretical and Modeling Approaches; Regional Research Institute, West Virginia University: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2020; Available online: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/rri-web-book (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Getaneh, Z.A.; Demissew, S.; Woldu, Z. Spatiotemporal dynamics of land use land cover change and its drivers in the western part of Lake Abaya, Ethiopia. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibaba, W.T.; Demissie, T.A.; Miegel, K. Drivers and Implications of Land Use/Land Cover Dynamics in Finchaa Catchment, Northwestern Ethiopia. Land 2020, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedd, R.; Light, K.; Owens, M.; James, N.; Johnson, E.; Anandhi, A. A synthesis of land use/land cover studies: Definitions, classification systems, meta-studies, challenges and knowledge gaps on a global landscape. Land 2021, 10, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiagarajan, K.; Manapakkam Anandan, M.; Stateczny, A.; Bidare Divakarachari, P.; Kivudujogappa Lingappa, H. Satellite images classifications using a hierarchical ensemble learning and correlations coefficient-based gravitational search algorithm. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, H.; Siraj, T.; Setu, S.J.; Anwar, M.M.; Rahman, M.A. Machine learning approach towards satellite image classification. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Trends in Computational and Cognitive Engineering: Proceedings of TCCE 2020, Saver, Bangladesh, 17–18 December 2020; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, H.; Shrestha, H.L.; Murthy, M.S.R.; Phuntso, P.; Pradhan, S.; Bajracharya, B.; Shrestha, B. Decadal dynamics of land covers changes in Bhutan. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 148, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.S.; Kuuire, V.; Kepe, T. On mapping urban community resilience: Land use vulnerability, coping and adaptive strategies in Ghana. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, R.S.; Kruska, R.L.; Muthui, N.; Taye, A.; Wotton, S.; Wilson, C.J.; Mulatu, W. Land-uses and land-covers dynamics in response to climatic, ecological, and sociopolitical changes: The case of southern Ethiopia. Landsc. Ecol. 2000, 15, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Geist, H.J. Land-Use and Land-Cover Change: Local Processes and Global Impacts; Lambin, E.F., Geist, H., Eds.; IGBP Series; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Yue, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W. Ecological effects associated with land-use change in China’s southwest agricultural landscape. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2006, 13, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Weng, Q.; Wang, Y. Land uses and covers changes in Guangzhou, China, from 1998 to 2003, using Landsat TM/ETM+ imagery. Sensors 2007, 7, 1323–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, E.L.; Honda, K. Biophysical and policy drivers of landscape changes in a central Vietnamese district. Environ. Conserv. 2007, 34, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsegaye, D.; Moe, S.R.; Vedeld, P.; Aynekulu, E. Dynamics of land covers and uses in Ethiopia’s Northern Afar rangelands. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2010, 139, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, M.; Parid, M.M.; Aini, Z.N.; Michinaka, T. A proximate and underlying cause of forest covers changes in Peninsular Malaysia. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 44, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J.R.; Kemp, D.; Lechner, A.M.; Ern, M.A.L.; Lèbre, É.; Mudd, G.M.; Bebbington, A. Increasing mine waste will induce land cover change that results in ecological degradation and human displacement. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongratz, J.; Reick, C.; Raddatz, T.; Claussen, M. A reconstruction of global agricultural areas and land covers for the last millennium. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 2008, 22, GB3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Ghazali, S.; Azadi, H.; Skominas, R.; Scheffran, J. Agricultural land conversion and ecosystem services loss: A meta-analysis. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 23215–23243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geremew, A.A. Evaluating the Effects of Changing Land Covers and Uses on A Watershed’s Hydrology: A Case Study of Ethiopia’s Gigel-Abbay Watershed in the Lake Tana Basin. Master’s Thesis, Universidade NOVA de Lisbo, Lisbon, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Belay, T.; Mengistu, D.A. Dynamics and determinants of land uses and covers in the Muga watershed of Ethiopia’s Upper Blue Nile basin. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2019, 15, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Meyfroidt, P.; Rueda, X.; Blackman, A.; Börner, J.; Cerutti, P.O.; Wunder, S. Effectiveness and synergies of policy instruments for land uses governance in tropical regions. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 28, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H.; Al-Maadeed, M. Agri-food markets in Qatar: Drivers, trends, and policy responses. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeleke, G.; Hurni, H. The impact of land uses and land covers dynamics on mountain resources degradations in the Northwestern Ethiopian highlands. Mt. Res. Dev. 2001, 21, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsalu, A.; Stroosnijder, L.; de Graaff, J. Long-term land resource dynamics and driving forces in Ethiopia’s Beressa watershed, highlands. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 83, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garedew, E.; Sandewall, M.; Söderberg, U.; Campbell, B.M. Land uses and covers patterns in Ethiopia’s central rift valley. Environ. Manag. 2009, 44, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megersa, T.; Nedaw, D.; Argaw, M. The combined influence of land uses/covers type and slope gradient on sediment and nutrient losses in in the Chancho and Sorga sub-watersheds, East Wollega Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia. Environ. Syst. Res. 2019, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidane, M.; Bezie, A.; Kesete, N.; Tolessa, T. The impact of land use and land cover (LULC) dynamics on soil erosion and sediment yield in Ethiopia. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabite, G.; Muleta, M.K.; Gessesse, B. Spatiotemporal land covers patterns and factors in Ethiopia’s Dhidhessa River Basin. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2020, 6, 1089–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negassa, M.D.; Mallie, D.T.; Gemeda, D.O. Forest covers change detection using Geographic Information Systems and remote sensing techniques: A spatiotemporal study of the Komto Protected Forest Priority Area in East Wollega Zone, Ethiopia. Environ. Syst. Res. 2020, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedajo, G.K.; Muleta, M.K.; Gessesse, B.; Koriche, S.A. Changes in the spatial and temporal greenness of vegetation in Ethiopia’s Dhidhessa River Basin. Environ. Syst. Res. 2019, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisa, M.B.; Negash, D.A.; Merga, B.B.; Gemeda, D.O. An impact of land-uses and land-covers changes on soil erosion using the RUSLE model and the geographic information system: A case of Temeji watershed, Western Ethiopia. J. Water Clim. Change 2021, 12, 3404–3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshome, D.S.; Moisa, M.B.; Gemeda, D.O.; You, S. Changes in land uses and land covers affects soil erosion and sediment output in Ethiopia’s Muger Sub-basin, Upper Blue Nile Basin. Land 2022, 11, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birhane, E.; Ashfare, H.; Fenta, A.A.; Hishe, H.; Gebremedhin, M.A.; Solomon, N. Land uses and covers changes along topographic gradients in the Hugumburda national forest priority region, Northern Ethiopia. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2019, 13, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsalu, G.; Mekonen, Y. GIS-Based Land Use and Land Cover Change Assessment Around Assosa District, Upper Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Prot. Policy 2024, 12, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J.A.; DeFries, R.; Asner, G.P.; Barford, C.; Bonan, G.; Carpenter, S.R.; Snyder, P.K. Worldwide consequences of land uses. Science 2005, 309, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, M.A.; Auch, R.F.; Karstensen, K.A.; Sayler, K.L.; Taylor, J.L.; Loveland, T.R. Land changes variability and human-environment dynamics in the Great Plains of the United States. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 710–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Yang, L.; Danielson, P.; Homer, C.; Fry, J.; Xian, G. Comprehensive changes detection method for updating the National Land Cover Database to about 2011. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 132, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, M.W.; Abebe, B.G.; Bantider, A. Physical and social drivers of land use and land cover change in Hawassa City, Ethiopia. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1203529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prenzel, B. Remote sensing-based quantification of land-covers and land-uses changes for planning. Prog. Plan. 2024, 61, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Alam, M.T.; Mojumder, P.; Mondal, I.; Kafy, A.A.; Dutta, M.; Mahtab, S.B. Dynamic assessment and prediction of land use alterations influence on ecosystem service value: A pathway to environmental sustainability. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 21, 100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, C.; Green, G.M.; Grove, J.M.; Evans, T.P.; Schweik, C.M. A Review and Assessment of Land-Use Change Models: Dynamics of Space, Time, and Human Choice; General Technical Report NE-297; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2002; Volume 61. [CrossRef]

- Jasrotia, A.S.; Bhagat, B.D.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, R. Remote sensing and GIS technique for delineating groundwater potential and quality zones in Western Doon Valley, Uttarakhand, India. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2013, 41, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yismaw, A.; Gedif, B.; Addisu, S.; Zewudu, F. Forest covers changes detection using remote sensing and GIS in Banja district, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Monit. Anal. 2014, 2, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, J.S.; Kumar, M. Monitoring land uses/covers changes by using remote sensing and GIS techniques: Case study of Hawalbagh block, district Almora, Uttarakhand, India. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2015, 18, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, S.; Singh, R. A comprehensive review on land use/land cover (LULC) change modeling for urban development: Current status and future prospects. Sustainability 2023, 15, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basanna, R.; Wodeyar, A.K. Supervised classification for LULC change analysis. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2013, 66, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, A.; Teferie, B. Use Google Earth to evaluate the accuracy of land uses and land covers classifications. Am. J. Environ. Prot. 2015, 4, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hattab, M.M. Using post-classification change detection techniques to monitor Egyptian coastal zone (Abu Qir Bay). Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2016, 19, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewabe, D.; Fentahun, T. Using remote sensing to evaluate land uses and detect changes in land covers in the Lake Tana Basin in Northwest Ethiopia. Cogent Environ. Sci. 2020, 6, 1778998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, D.; Bano, S.; Khan, N. Spatio-temporal analysis of urbanization effects: Unravelling land use and land cover dynamics and their influence on land surface temperature in Aligarh City. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yourek, M.; Liu, M.; Scarpare, F.V.; Rajagopalan, K.; Malek, K.; Boll, J.; Adam, J.C. Downscaling global land-use/cover change scenarios for regional analysis of food, energy, and water subsystems. Front. Environ. Science 2023, 11, 1055771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayra, J.; Kivinen, S.; Keski-Saari, S.; Poikolainen, L.; Kumpula, T. Using historical maps to identify long-term changes in land uses and covers. Ambio 2023, 52, 1777–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco Quevedo, R.; Velastegui-Montoya, A.; Montalván-Burbano, N.; Morante-Carballo, F.; Korup, O.; Daleles Rennó, C. Literature review on the role of land uses and covers in determining landslide susceptibility. Landslides 2023, 20, 967–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parece, T.E.; Campbell, J.B. Overview of geospatial technology and land uses/covers monitoring. Adv. Watershed Sci. Assess. 2015, 33, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Thenkabail, P.S.; Gumma, M.K.; Teluguntla, P.; Poehnelt, J.; Congalton, R.G.; Thau, D. Croplands mapping in continental Africa with cloud computing with Google Earth Engine automated. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2017, 126, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Goparaju, L.; Qayum, A. Land uses and land covers analysis of urban environments utilizing the Markov chain predictive model in Ranchi, India. Spat. Inf. Res. 2017, 25, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheer, S.; Wang, X.; Farooque, A.A.; Nawaz, R.A.; Liu, K.; Adekanmbi, T.; Liu, S. A comparison of land uses and land covers classifiers utilizing various satellite images and machine learning algorithms. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K.; Liang, S.; Zhang, N.; Wei, X.; Gu, X.; Zhao, X.; Xie, X. Land covers classifications using finer resolution remote sensing data and temporal variables extracted from time series coarser resolution data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 93, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A.H.; Abbasi, H.; Karas, I.R. A review on change detection method and accuracy assessment for land covers and land uses. Appl. Remote Sens. Soc. Environ. 2021, 22, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C. Potential impact of human-induced land covers changes on East Asia monsoon. Int. Planet. Change 2003, 37, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerschman, J.P.; Paruelo, J.M.; Bella, C.D.; Giallorenzi, M.C.; Pacin, F. Land covers classifications in the Argentine Pampas based on multitemporal Landsat TM data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2003, 24, 3381–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Goward, S.N.; Schleeweis, K.; Thomas, N.; Masek, J.G.; Zhu, Z. Case studies of the eastern United States used Landsat data to examine the dynamics of national forests. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, 14301442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, R.; Odeh, I.O.; Ancev, T. Improving the Accuracy of Land Use and Land Cover Classification of Landsat Data Using Post-Classification Enhancement. Remote Sens 2009, 1, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaschke, T. Object based image analysis for remote sensing. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens 2010, 65, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashutosh, S.; Roy, P.S. Three decades of nationwide forest cover mapping using Indian remote sensing satellite data: A success story of monitoring forests for conservation in India. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2021, 49, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichera, C.R.; Modica, G.; Pollino, M. Land Covers classifications and change-detection analysis using multi-temporal remote sensed image and landscape metrics. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2012, 45, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkuo, E.K.; Frimpong, A. Analysis of forest covers change detection. Int. J. Remote Sens. Appl. 2012, 2, 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Baynard, C.W. Remote sensing applications: Beyond Land uses and covers changes. Adv. Remote. Sens. 2013, 2, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmail, M.; Masria, A.L.I.; Negm, A. Monitoring land uses and covers changes around Damietta Promontory, Egypt, using RS/GIS. Procedia Eng. 2016, 154, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Schaaf, C.B.; Sun, Q.; Kim, J.; Erb, A.M.; Gao, F.; Papuga, S.A. Monitoring land surface albedo and vegetation changes with Landsat’s high geographic and temporal resolution synthetic time series and the MODIS BRDF/NBAR/albedo product. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinform. 2017, 59, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.I.; Basak, R. Land covers changes identification using GIS and remote sensing techniques: A spatiotemporal study of Tanguar Haor in Sunamganj, Bangladesh. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2017, 20, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, H.; Adamowski, J.; Bonnell, R.; Sharifi, F.; Namdar, M.; Ale-Ebrahim, S. Land uses and land covers classifications over a large areas in Iran based on single date analysis of satellite image. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2011, 66, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vali, A.; Comai, S.; Matteucci, M. Deep learning for land use and land cover classification based on hyperspectral and multispectral earth observation data: A review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Q.; Olofsson, P.; Zhu, Z.; Tan, B.; Woodcock, C.E. Toward near real-time monitoring of forest disturbances by fusion of MODIS and Landsat data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 135, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassi, A.; Vizzari, M. Object-oriented lulc categorization in the Google Earth engine using snic, glcm, and machine learning methods. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, S.; Singha, P.; Mahato, S.; Pal, S.; Liou, Y.A.; Rahman, A. Review of land-uses and covers classifications using machine learning classifiers with the help of satellite observations. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, L.J.; Bagnoli, M.; Focacci, M. Analysis of land-cover/use change dynamics in Manica Province in Mozambique in a period of transition (1990–2004). For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 254, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, K.; Conway, D. Assessing the dynamics of land uses and changes in the forest covers in the Bara district of Nepal (1973–2003). Hum. Ecol. 2018, 36, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afuye, G.A.; Nduku, L.; Kalumba, A.M.; Santos, C.A.G.; Orimoloye, I.R.; Ojeh, V.N.; Sibandze, P. Global trend assessment of land use and land cover changes: A systematic approach to future research development and planning. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2024, 36, 103262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.C.; Loveland, T.R. A review of Landsat data used to monitor huge areas of land covers changes. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 122, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Alemneh, Y.; Biazen Molla, M. Spatio-temporal dynamics and drivers of land use land cover change in Farta district South Gonder, Ethiopia. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2024, 43, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abir, F.A.; Saha, R. Spatiotemporal analysis of the land surface temperature and land cover fluctuation in Pabna municipality, Bangladesh, during the winter. Environ. Chall. 2021, 4, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onacillova, K.; Krištofová, V.; Paluba, D. Google Earth Engine automatically classifies forest covers using Sentinel-2 multispectral satellite image and machine learning techniques. Acta Geogr. Univ. Comen. 2023, 67, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Şenol, C.; Taş, M.A. Trends in land use patterns in the Terkos Lake basin from 1980 to 2023, as well as their associated impact on natural ecosystems. Front. Life Sci. Relat. Technol. 2023, 4, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebjalal, E.; Dashtekian, K. Analysis of changes in land covers and land uses utilizing classifications and differencing techniques based on the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI). Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 8, 4614–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, M.; Taylor-Powell, E. Analyzing qualitative data. In Program Development Evaluation; University of Wisconsin-Extension Cooperative Extension: Taconite, MI, USA, 2013; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Næss, J.S.; Iordan, C.M.; Huang, B.; Zhao, W.; Cherubini, F. Recent global land covers changes and their implications for soil erosion and carbon loss owing to deforestation. Anthropocene 2021, 34, 100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, P.; Turubanova, S.; Hansen, M.C.; Tyukavina, A.; Zalles, V.; Khan, A.; Cortez, J. Global maps of cropland extent and changes show accelerated cropland expansions in the twenty-first century. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, E.L.; Healey, S.P.; Yang, Z.; Oduor, P.; Gorelick, N.; Omondi, S.; Cohen, W.B. Three decades of East Africa’s shifting land cover. Land 2021, 10, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gashaw, T.; Tulu, T.; Argaw, M.; Worqlul, A.W. Modeling the hydrological impacts on Land uses and covers changes in the Andassa watershed, Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619, 1394–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minta, M.; Kibret, K.; Thorne, P.; Nigussie, T.; Nigatu, L. Land uses and covers dynamics in the Dendi-Jeldu hilly-mountainous zones of central Ethiopia’s highlands. Geoderma 2018, 314, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betru, T.; Tolera, M.; Sahle, K.; Kassa, H. Trends and drivers of land uses and covers changes in Western Ethiopia. Appl. Geogr. 2019, 104, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degife, A.; Worku, H.; Gizaw, S.; Legesse, A. Land uses and covers patterns, drivers, and environmental implications in Ethiopia’s Lake Hawassa Water shed. Remote Sens. Appl. Incl. Soc. Environ. 2019, 14, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abera, W.; Tamene, L.; Tibebe, D.; Adimassu, Z.; Kassa, H.; Hailu, H.; Verchot, L. Characterizing and evaluating the impacts of national land restoration initiatives on ecosystem services in Ethiopia. Land Degrad. Dev. 2020, 31, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailu, A.; Mammo, S.; Kidane, M. Land uses dynamics; land covers changes trend, and drivers in Western Ethiopia’s Jimma Geneti District. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogato, G.S.; Bantider, A.; Geneletti, D. Dynamics of land uses and land covers changes in Huluka watershed of Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. Environ. Syst. Res. 2021, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisay, G.; Gitima, G.; Mersha, M.; Alemu, W.G. Assessment of land use land cover dynamics and its drivers in Bechet Watershed Upper Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2021, 24, 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinka, M.O.; Chaka, D.D. Analysis of land uses/land covers change in Ethiopia, Adei watershed, Central Highlands. J. Water Land Dev. 2019, 41, 146–153. Available online: https://journals.pan.pl/Content/112874/PDF/Dinka%20Chaka%20360.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Solomon, N.; Hishe, H.; Annang, T.; Pabi, O.; Asante, I.K.; Birhane, E. Forest covers changes, main factors, and community perceptions in the Wujig Mahgo Waren forest in northern Ethiopia. Land 2018, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu, F.; Tolera, M.; Tesfaye, G. The drivers of the land uses and covers change pattern in the Somodo Watershed in the southwest of Ethiopia. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2019, 14, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifawesen, S. Assessment of the key drivers of forest covers changes and its associated livelihood impacts in Yabello district, Borana zone, Ethiopia. Int. J. Sustain. Green Energy 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, B.T. Assessing the Uptake of Sustainable Land Management Programs Towards Improved Land Management, Tenure Security, Food Security, and Agricultural Production: Evidence from South Wello, Ethiopia. DANS Data Station Physical and Technical Sciences, V1. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, B.; Garedew, E.; Eshetu, Z.; Kassa, H. Changes in land uses and covers, as well as the driving reasons behind them, in Ethiopia’s northwestern lowlands. Int. Res. J. Agric. Sci. Soil Sci. 2015, 5, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshesha, T.W.; Tripathi, S.K.; Khare, D. GIS and remote sensing analyses of the dynamics of land uses and land cover changes in the Beressa Watershed in Ethiopia’s Northern Central Highland between 1984 and 2015. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2016, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addisie, M.B.; Molla, G.; Teshome, M.; Ayele, G.T. Assessing biophysical conservation techniques in Ethiopia’s highlands in relation to dynamic land uses and land covers. Land 2022, 11, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melese, S.M. Effect of Land Use Land Cover Changes on the Forest Resources of Ethiopia. Int. J. Nat. Resour. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 1, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuma, H.G.; Feyessa, F.F.; Demissie, T.A. Land-use/land-cover Changes and Implications in Southern Ethiopia: Evidence from Remote Sensing and Informants. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Worku, H. Simulating urban land uses and covers dynamics using cellular automata and Markov chain approach in Addis Ababa and the surrounding. Urban Clim. 2020, 31, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othow, O.O.; Gebre, S.L.; Gemeda, D.O. Analyzing the pace of land uses and covers changes, as well as identifying the causes of forest covers changes in Gog district, Gambella regional state, Ethiopia. J. Remote Sens. GIS 2017, 6, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nega Emiru, N.E.; Heluf Gebrekidan, H.G.; Degefe Tibebe, D.T. Analyzing changes in land covers and uses in mixed crop-livestock systems in western Ethiopia: Senbat watershed (case study). J. Water Land Dev. 2019, 41, 146–153. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264858965_Analysis_of_land_useland_cover_changes_in_western_Ethiopian_mixed_crop-livestock_systems_the_case_of_Senbat_watershed (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Dinka, M.O. Analysing decadal land uses/covers dynamics of the Lake Basaka catchment (Main Ethiopian Rift) using LANDSAT imagery and GIS. Lakes Reserv. Res. Manag. 2012, 17, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassa, H.; Dondeyne, S.; Poesen, J.; Frankl, A.; Nyssen, J. Transition from forest-based to cereal-based agricultural systems: Review of the drivers of land uses changes and degradations in Southwest Ethiopia. Land Degrad. Dev. 2017, 28, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshesha, T.M.; Tsunekawa, A.; Haregeweyn, N.; Tsubo, M.; Fenta, A.A.; Berihun, M.L.; Kassa, S.B. Agroecology-based land uses and covers changes detection, prediction, and implications for land degradation: A case study from the Upper Blue Nile Basin. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2024, 12, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshesha, D.T.; Tsunekawa, A.; Tsubo, M.; Ali, S.A.; Haregeweyn, N. Land-uses changes and its socio-environmental consequences in eastern Ethiopia’s highlands. Reg. Environ. Change 2014, 14, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathewos, M.; Lencha, S.M.; Tsegaye, M. Land use and land cover change assessment and future predictions in the Matenchose Watershed, Rift Valley Basin, using CA-Markov simulation. Land 2022, 11, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruijnzeel, L.A. Tropical forest hydrological functions: Can’t see the soil through the trees? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004, 104, 185–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, P.; Pons, X.; Saurí, D. Land-covers and land-uses changes in a Mediterranean landscape: A spatial analysis of driving forces integrating biophysical and human factors. Appl. Geogr. 2008, 28, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlay, R.; Kavdir, Y. The effect of land covers type on soil aggregate stability and erodibility. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, M.; Belay, K. Factors influencing the adoptions of soil conservation methods in southern Ethiopia: The Gununo area. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in Tropics and Subtropics. JARTS 2004, 105, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hailu, Y.; Tilahun, B.; Kerebeh, H.; Tafese, T. Detecting changes in land covers and uses in Southwest Ethiopia’s Gibe Sheleko National Park. Agric. Resour. Econ. Int. Sci. E-J. 2018, 4, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakeristanan, M.L.; Md Said, M.A. Land uses and covers change detection utilizing a remote sensing application for land sustainability. In Proceedings of the AIP, American Institute of Physics, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 26 September 2012; pp. 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derebe, M.A.; Hatiye, S.D.; Asres, L.A. Dynamics and Prediction of Land Uses and Covers Changes Using Geospatial Techniques in the Abelti Watershed, Omo Gibe River Basin, Ethiopia. Adv. Agric. 2022, 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondrade, N.; Dick, Ø.B.; Tveite, H. GIS based mapping of land covers changes utilizing multi-temporal remotely sensed images data in Lake Hawassa Watershed, Ethiopia. Environ. Monit. Eval. 2014, 186, 1765–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetene, A.; Hilker, T.; Yeshitela, K.; Prasse, R.; Cohen, W.; Yang, Z. Detecting trends in landuse and land covers changes of Nech Sar National Park, Ethiopia. Environ. Manag. 2016, 57, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lira, P.K.; Tambosi, L.R.; Ewers, R.M.; Metzger, J.P. Changes in land covers and uses in the landscapes of the Atlantic Forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 278, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ya’acob, N.; Azize, A.B.M.; Mahmon, N.A.; Yusof, A.L.; Azmi, N.F.; Mustafa, N. Temporal forest changes detection and forest health assessment by using Remote Sensing. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2014; Volume 19, p. 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congalton, R.G. A review of assessing the accuracy of classifications of remotely sensed data. Remote Sens. Environ. 1991, 37, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera, A.J.; Garrett, J.M. Understanding inter observer agreement: The kappa statistic. Fam. Med. 2005, 37, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).