Abstract

The global carbon cycle has become increasingly unbalanced over the past century as anthropogenic fluxes into the atmosphere far exceed the sequestration capacity of land and ocean systems. Data from 2025 show estimated annual anthropogenic emissions of ≈11.2 gigatonnes of carbon (GtC), while only ≈5.6 GtC are sequestered by land and ocean sinks mainly provided by photosynthetic CO2 fixation. The resulting surplus of carbon emissions has led to a doubling of atmospheric CO2 concentrations above pre-industrial values to ≈430 ppm, which is a major driver of increasingly erratic climatic phenomena. Recent data indicate that fossil fuel use will continue rising up to and beyond 2050, largely negating the drive to cut CO2 emissions as recommended by the IPCC and other reputable transnational bodies. Hence, there is an urgent need to reduce atmospheric CO2 levels via carbon sequestration. This review focuses on the proven capacity of biological mechanisms to sequester CO2 at a global scale with an annual capacity in the range of gigatonnes of carbon. New measures such as re- and a-forestation, plus improved and more sustainable management of tropical tree crops, can further increase the carbon sequestration potential of these plants. By implementing these and other nature-based solutions, the highly productive tropical vegetation belt could contribute an additional 1–2 Gt of carbon sequestration via natural forests and perennial tree crops. In order to expedite this process, we examine the use of new modalities of transparent carbon trading systems that include selected tropical crops. As highlighted at COP30 in Brazil and elsewhere, this would enable tropical countries to derive benefit for costs incurred in land management changes such as reforestation, regenerative farming, and intercropping to benefit smallholders and other rural communities. In particular, carbon finance is emerging as a critical driver, with appropriately regulated and transparent carbon credit schemes offering fungible monetary compensation for climate-positive land management.

1. Introduction

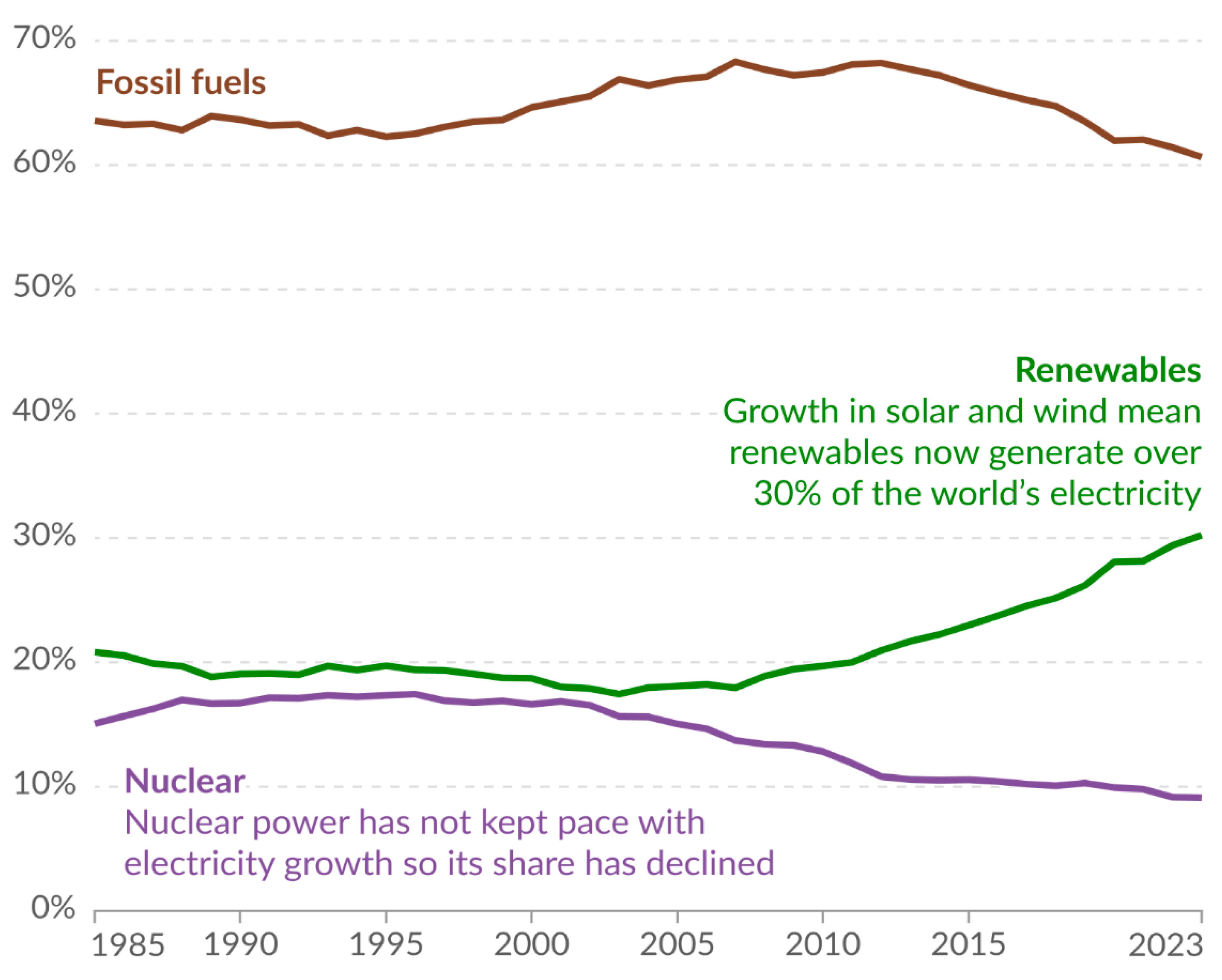

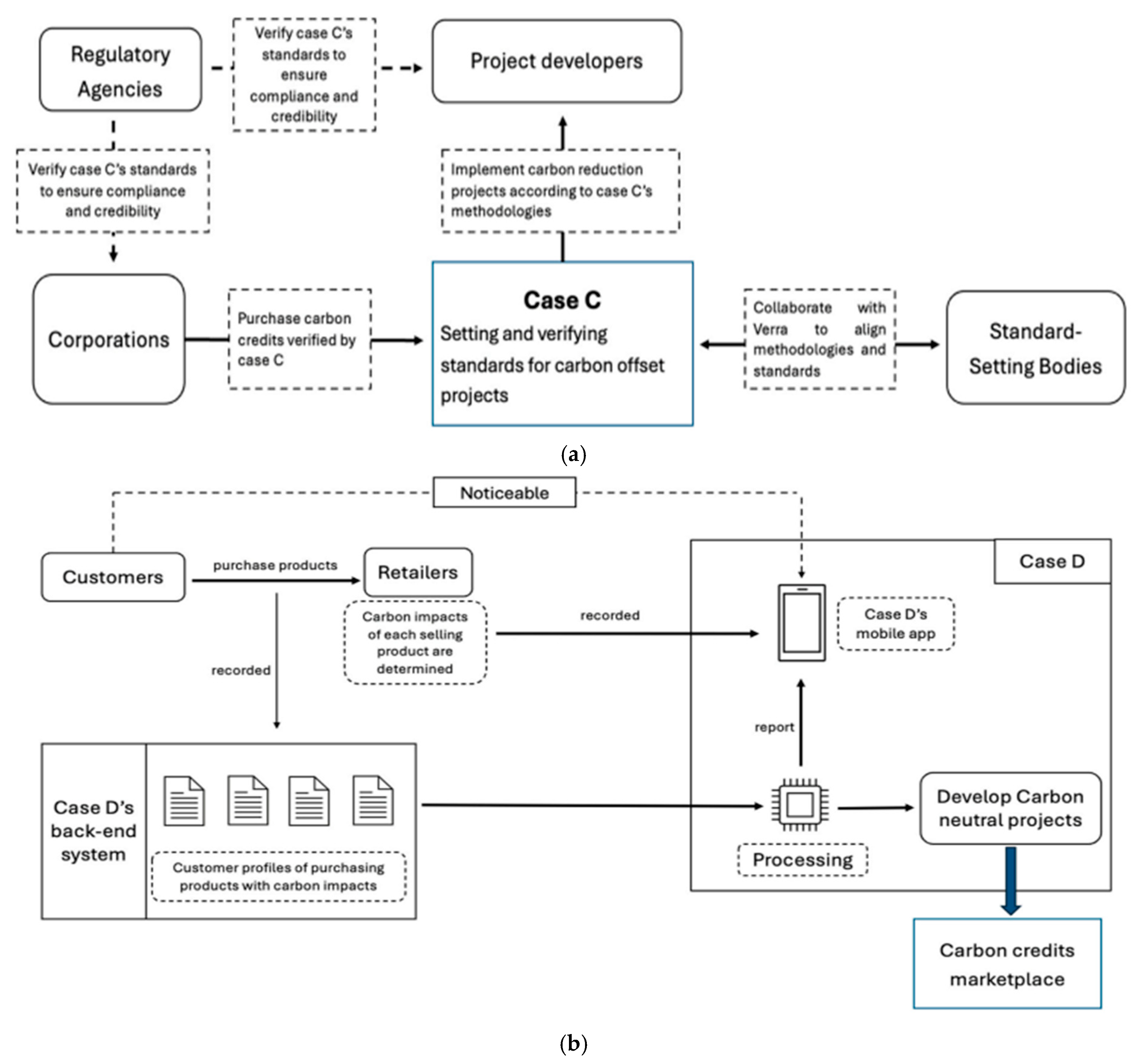

Since the 1950s, the global carbon cycle has become increasingly unbalanced as anthropogenic CO2 emissions have overtaken the planetary carbon sequestration capacity provided by photosynthesis [1]. As a result, atmospheric CO2 levels have doubled from pre-industrial values to ≈430 ppm, with attendant climatic effects caused by this potent greenhouse gas (GHG). Despite over four decades of mitigation efforts, recent data [2] show that CO2-emitting fossil fuels still account for more than 60% of global electricity generation (see Figure 1). Moreover, the rise in renewables, such as solar, wind, and hydro power, has been largely offset by a decline in carbon-free nuclear sources, as many power stations have been closed down or have reached the end of their productive lifetimes since 2000 [2].

Figure 1.

Percentage contribution of the three major sources of global electricity generation since 1985. Graphic from [2].

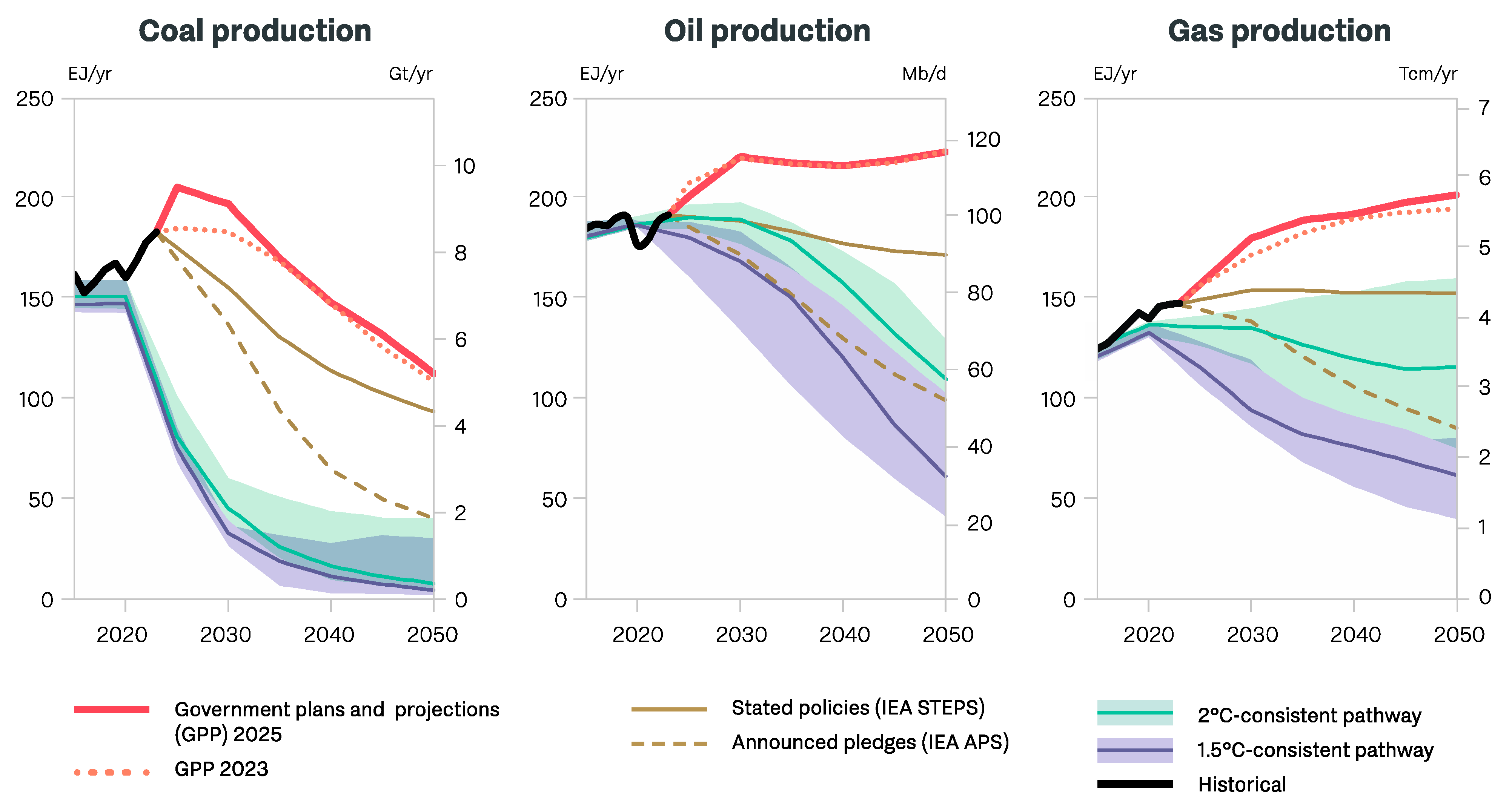

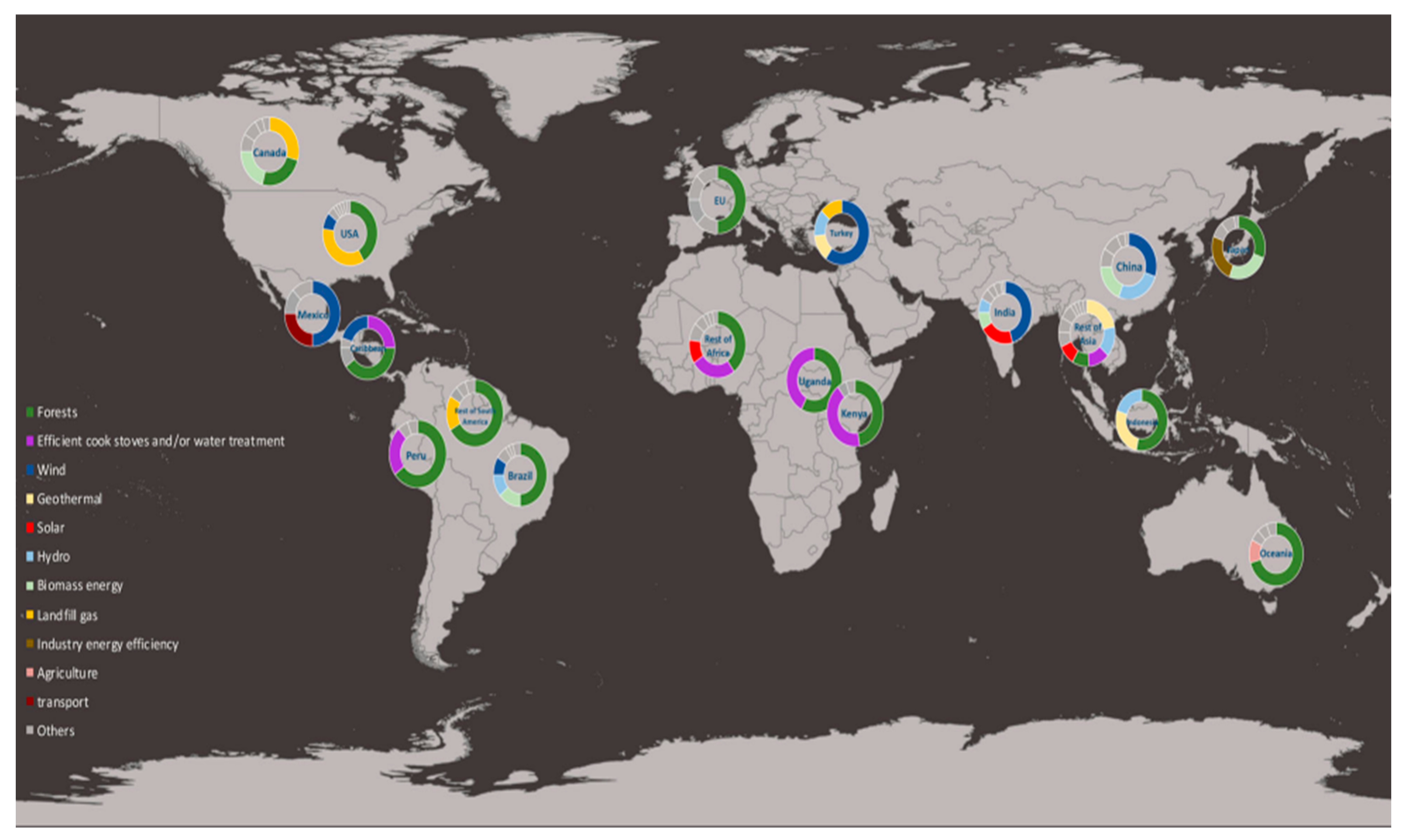

Despite several decades of commitments to reduce GHG emissions by governments and private companies across the world, there were increasing indications of rollbacks in such pledges in 2025 [3]. Also, fossil fuel consumption has continued to increase over the past decade. For example, Figure 2 shows that major global economies have projected increases in both oil and gas production at least up to 2050 [4,5]. Indeed, during 2025 there was an increase in granting permissions to search for new sources of fossil fuels. Additionally, in 2025, global temperatures reached 1.54 °C above pre-industrial levels, with the three-year average for 2023–2025 on track to exceed the key 1.5 °C milestone for the first time [6]. In view of these findings, the prospects for declines in emissions over the next few decades, which are a feature of most current climate models, including those of the IPCC and the UN, require re-examination [7].

Figure 2.

Global coal, oil, and gas production under six pathways from 2015 to 2050 based on current government plans. Principal data in exajoules (EJ) per year. Physical units for each fossil fuel are shown as secondary axes: billion tonnes per year (Gt/yr) for coal, million barrels per day (Mb/d) for oil, and trillion cubic meters per year (Tcm/yr) for gas, showing projected increases in both oil and gas production at least up to 2050. The graphic is from data provided in [4].

To summarize, it is becoming increasingly clear that current policies that rely mainly on reining in CO2 emissions, however laudable they are in principle, are at variance with the harsh realities that we face in the post-2025 era. Moreover, even if drastic cuts in CO2 emissions can be achieved by the end of the 21st century, global atmospheric CO2 levels will still likely exceed 500 ppm and could be as high as 1000 ppm [8,9,10]. In either case, the kinds of adverse global climatic excursions that are already evident would then be of considerably greater magnitude, with serious global ramifications for the future of human societies and biological systems. Moreover, it is likely that these elevated CO2 levels would persist for centuries before pre-industrial levels could be restored. This highlights the urgency of considering the second major component of the global carbon cycle, namely the sequestration or removal of excess CO2 from the atmosphere via carbon sinks, of which the most effective is plant-based photosynthesis [1].

The enhancement of carbon sinks is indispensable for achieving the Paris Agreement targets [11,12]. In particular, biological carbon sequestration is the most scalable and cost-effective solution capable of significantly reducing atmospheric CO2 concentrations and stabilizing global temperatures. Carbon sequestration reduces atmospheric CO2 levels primarily through photosynthesis and subsequent carbon storage in standing biomass and in other durable organic pools. Numerous studies highlight the unparalleled role of biological sequestration in mitigating climate change relative to engineered removals [13,14]. Biological systems not only capture and store CO2 efficiently but also provide co-benefits such as biodiversity support, soil formation, and ecosystem resilience functions increasingly recognized as essential in climate adaptation strategies [15,16].

Globally, the spatial distribution of biological carbon sequestration is dominated by vegetation in the humid tropics in a belt between latitudes 10° N and 10° S. Here, highly productive forests and perennial crops flourish, especially in the Amazon and Congo river basins and the Indo–Malay archipelago. These tropical ecosystems account for the world’s largest terrestrial carbon fluxes, absorbing many gigatonnes of CO2 annually, some of which are sequestered over timescales ranging from decades to centuries [1,17]. Tropical forests store vast carbon stocks in above- and below-ground biomass, while long-lived perennial crops such as oil palm, rubber, cocoa, and coconut contribute significantly to continuous carbon capture due to their rapid growth and year-round photosynthetic activity [18]. The high productivity, extensive canopy structure, and long rotation cycles make these ecosystems among the most efficient biological carbon sinks.

Recent studies report that tropical perennial crops can sequester between 5 and 64.5 tonnes of CO2 per hectare annually depending on species and management intensity [18]. Oil palm and rubber plantations are often misunderstood as purely commercial monocultures, but they also possess considerable carbon sequestration potential due to substantial biomass accumulation in trunks, fronds, root systems, and soil organic carbon [18]. When managed appropriately, such crops can function as net carbon sinks throughout their productive lifespans, offering dual roles in climate mitigation and economic development. To further increase the sequestration potential of tropical forests and crops, various enhancement measures have been proposed. These include reforestation and afforestation programs, agroforestry integration, regenerative soil management to enhance soil organic carbon deposits, and sustainable intensification practices that boost both productivity and carbon storage [19,20].

Advances in remote sensing, drone-based biomass estimation, and artificial intelligence-assisted monitoring have improved precision in carbon stock measurements, which are a prerequisite for credible reporting under carbon market frameworks [21,22,23]. Alongside such technological improvements, policy frameworks supporting the shift toward a bioeconomy and the transition from deforestation-linked supply chains, together with carbon recovery initiatives and landscape-level restoration, continue to enhance overall carbon sequestration performance [24,25,26]. The adoption of enhanced biological carbon sequestration requires robust incentives, governance systems, and financial mechanisms. As discussed below, carbon finance is now emerging as a critical driver, with carbon credit schemes offering monetary compensation for climate-positive land management [27].

The objectives of this review are: (i). to assess the current evidence for the potential of nature-based solutions (NbS) involving tropical vegetation, including both natural and crop components, to contribute to a resetting of the global carbon cycle via net carbon storage and (ii). to critically examine recently emerging evidence for the development of a new generation of more transparent carbon trading systems using novel technologies and regulatory mechanisms. The overall working hypothesis is that updated and recalibrated carbon trading systems have the potential to catalyze the development of a range of nature-based solutions that could collectively address the current climate crisis by increasing global rates of carbon sequestration.

2. Roles of Carbon Sequestration in Reducing Atmospheric CO2 Levels

The climate crisis, driven by persistently rising anthropogenic emissions of CO2 and other GHGs, demands urgent and large-scale interventions. Decarbonization of fossil-dependent electricity generation, transport, and industrial processes such as cement manufacture remains indispensable. However, mitigation strategies are increasingly recognized as including the critical role of natural carbon sinks such as forests, wetlands, peatlands, grasslands, and agroecosystems in absorbing and storing atmospheric CO2. These ecosystems provide the most scalable, cost-efficient, and co-benefit-rich pathways for CO2 removal, complementing and surpassing largely unproven technological decarbonization measures such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) and direct air capture and storage (DACS), as recently discussed [8].

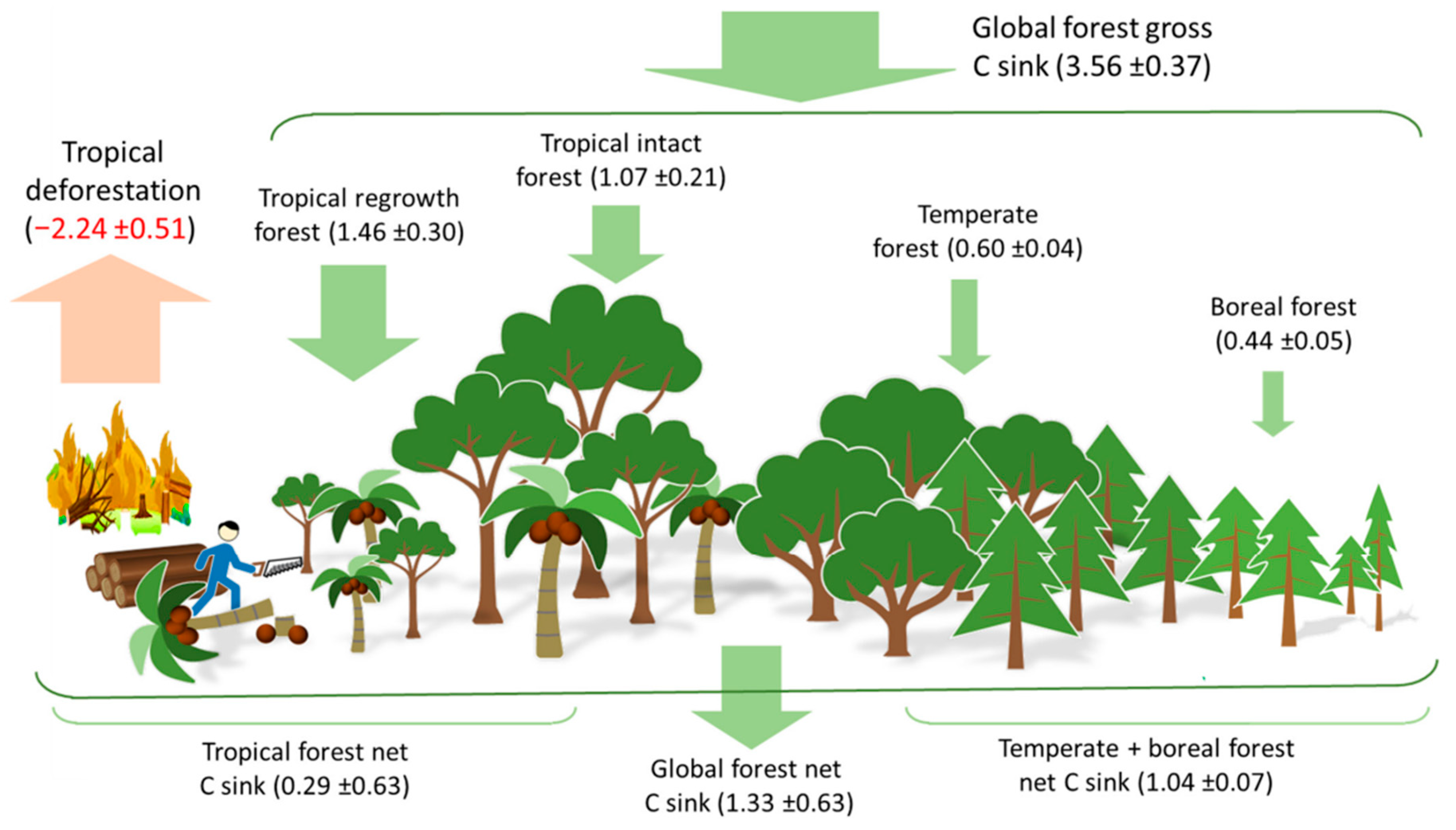

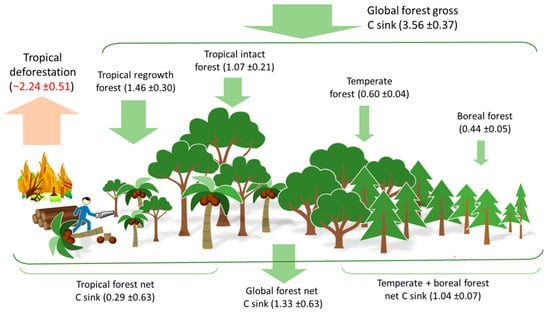

Terrestrial and oceanic ecosystems are by far the major carbon sinks on the planet. As shown in Figure 3, forests across all biomes have maintained an estimated 3.56 ± 0.37 Pg (Gt) C yr−1 sink over the past three decades, reflecting persistent and substantial CO2 uptake [28]. In addition, wetlands and peatlands, while covering only a small fraction of global land area, store disproportionately high carbon stocks, representing 20–30% of terrestrial organic carbon. Grasslands, restored ecosystems, and agroforestry systems also provide meaningful contributions to carbon storage, particularly when subjected to targeted restoration and sustainable land management [29].

Figure 3.

Forests across all biomes have maintained an estimated 3.5 ± 0.4 Pg C yr−1 sink over the past three decades, reflecting persistent and substantial CO2 uptake. Graphic from [28].

Despite the critical role of natural carbon sinks, global CO2 emissions remain far above net-zero trajectories, leading to extreme weather, sea-level rise, biodiversity loss, and ecosystem degradation. Enhancing carbon sequestration through ecosystem preservation, restoration, and sustainable management is thus essential. NbS are increasingly recognized in national and international strategies as both mitigation and adaptation tools, especially in biodiverse tropical regions. The Indo–Malay archipelago lies squarely within this tropical zone, benefiting from year-round rainfall, high insolation, and stable temperatures. These conditions support lowland dipterocarp forests and high-yield tropical perennial tree crops, such as oil palm [18] and rubber [30], which are among the most productive carbon-sequestering ecosystems worldwide.

The IPCC acknowledges that agroforestry systems can sequester between 1.06 and 55.47 t of CO2 ha−1 yr−1 depending on climate, soil type, and species composition [31]. Recent studies estimate that rubber plantations sequester 30.6–35.2 t of CO2 per hectare at age seven years [32] depending on age, soil, and management intensity, while oil palm plantations can sequester 20–64.5 t of CO2 ha−1 yr−1 under sustainable management, as recently reviewed in ref. [18] and outlined in papers cited therein. These tropical crop systems, often overlooked in climate finance discussions, present an opportunity to integrate agricultural landscapes into carbon market mechanisms, enhancing both mitigation and rural livelihoods. Beyond CO2 storage, they offer ecosystem services such as soil stabilization, water infiltration, microclimate regulation, and flood-risk reduction, which provide critical co-benefits for tropical nations experiencing increasingly variable rainfall and seasonal droughts.

Carbon sequestration in forests and perennial crops is intimately linked to hydrological regulation. Forested landscapes, mangroves, peatlands, and riparian agroforestry buffers absorb rainfall, reduce runoff, and mitigate peak flood flows while also enhancing groundwater recharge and buffering against seasonal drought [33,34]. These hydrological co-benefits, although historically undervalued in carbon markets, are gaining recognition as integral components of ecosystem-based climate adaptation strategies. By integrating flood-risk mitigation and drought resilience into carbon credit methodologies, the financial and social value of conserved or restored ecosystems can be amplified, particularly in tropical regions such as Southeast Asia and the Amazon basin.

The 2025 COP30 meeting held in Belém, Brazil, was the first climate-change conference hosted within a major tropical forest region, and it underscored the strategic significance of tropical forests in climate mitigation. Hosting COP30 in the heart of the Amazon signaled global intent to place forests and NbS at the center of climate policy. One landmark outcome was the launch of the Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF), a mechanism designed to channel long-term public and private investment toward countries that conserve and restore tropical ecosystems [35]. Under this fund, tropical-forest nations are eligible for predictable, results-based payments tied to verified conservation and carbon-enhancement outcomes, providing a sustainable financial incentive to protect standing forests and scale up restoration efforts [36,37]. As of early 2026, TFFF had already received over $6.7 billion from dozens of government donors [38].

Beyond carbon removal, COP30 reaffirmed the roles of tropical ecosystems in regulating water and soil systems, supporting biodiversity, safeguarding indigenous and local communities, and enhancing climate resilience. By integrating these services into carbon finance architecture, the TFFF represents a paradigm shift: forests, wetlands, and tropical crops are not merely ecological assets but central components of mitigation, adaptation, and social equity strategies. Major tropical forests, such as the Amazon, store 150–200 billion tonnes of carbon, equivalent to roughly 15–20 years of global CO2 emissions, yet deforestation and degradation persist. Simultaneously, tropical crop landscapes like oil palm and rubber plantations offer a largely untapped potential for carbon capture and hydrological co-benefits. By integrating these ecosystems into results-based financing mechanisms such as the TFFF, countries can align economic incentives with sustainable land management, climate mitigation, and adaptation priorities.

Effectively managed global-scale carbon sequestration by tropical forests and perennial crops is pivotal for addressing the climate crisis. For tropical nations, the convergence of ecological productivity, ecosystem services, and finance mechanisms such as the TFFF offers an opportunity to embed carbon sequestration as a central pillar of climate mitigation, adaptation, and sustainable development strategies. Terrestrial ecosystems, particularly tropical forests and perennial crop systems, are critical not only for mitigating the accumulation of greenhouse gases but also for stabilizing climate systems and supporting the broader ecological functions of the biosphere [39].

Photosynthetic assimilation in trees, shrubs, and perennial crops converts atmospheric CO2 into organic carbon compounds in stems, roots, leaves, and fruits, etc. Over time, some of this carbon becomes part of durable biomass pools and soil organic carbon, providing long-term storage over decades to centuries in tropical forest ecosystems. Tropical forests, with dense canopy structures and high net primary productivity, can sequester substantial amounts of CO2, averaging approximately 42.4 t of CO2 ha−1 yr−1 [18]. Perennial crops such as oil palm significantly contribute to continuous carbon uptake. Oil palm plantations under sustainable management have been shown to sequester as much as 64.5 t of CO2 ha−1 yr−1, highlighting their remarkable capacity as biological carbon sinks alongside natural forests [18]. In addition to being agricultural assets, these crops serve as consistent carbon sinks throughout their productive lifespans, effectively bridging the gap between food production, commodity supply, and climate mitigation as well as offsetting a significant fraction of anthropogenic emissions [18].

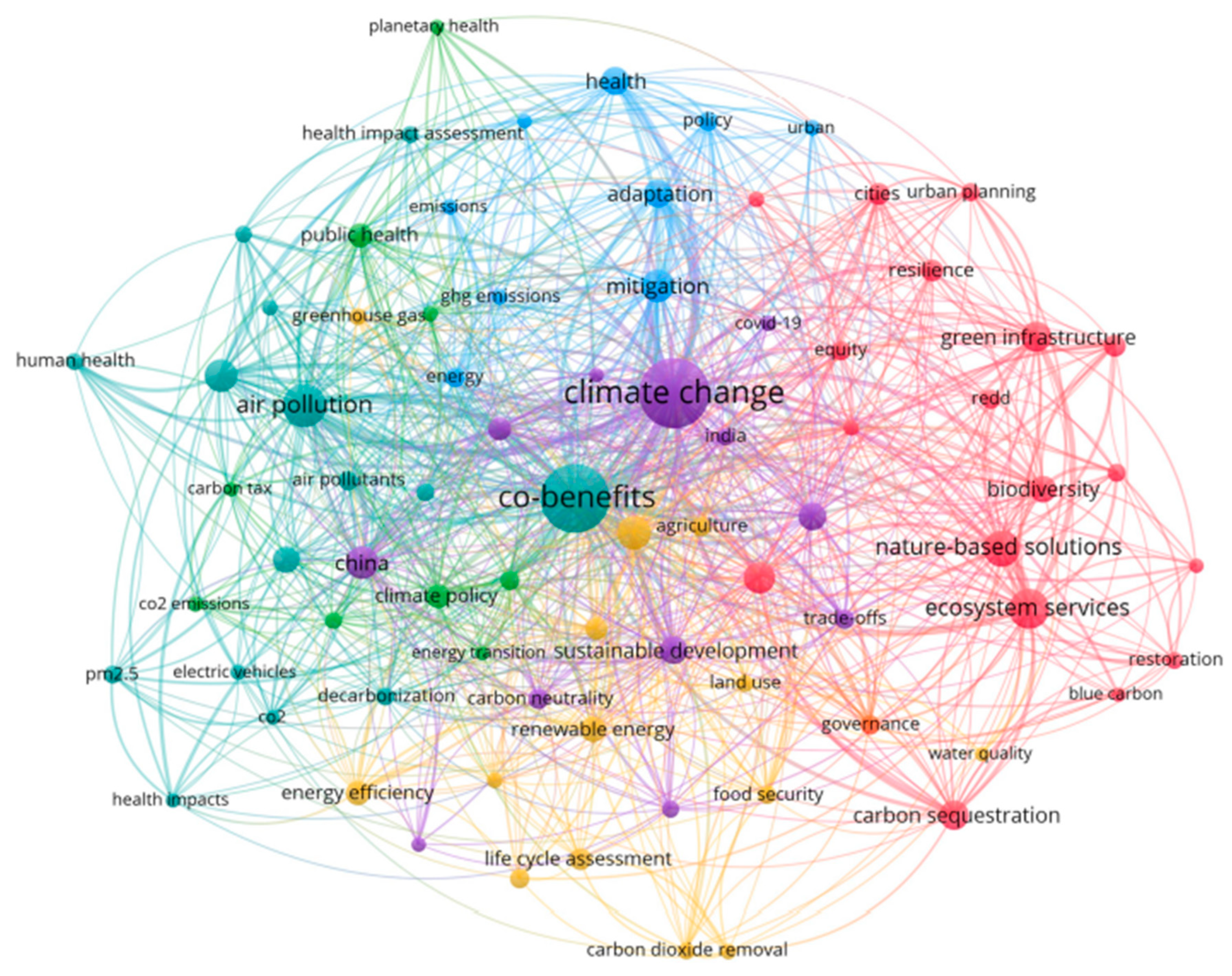

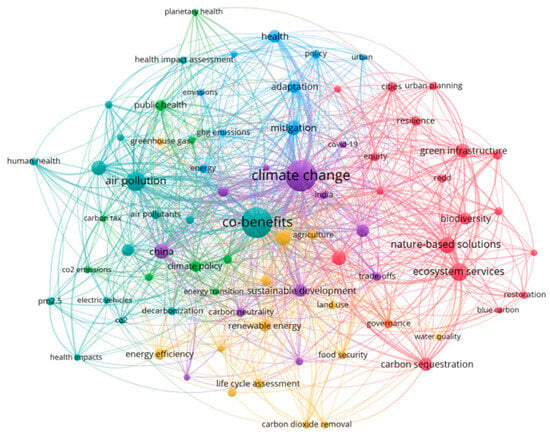

When complemented by other perennial crops, agroforestry systems, and restored wetland areas, these ecosystems form a robust, multi-layered carbon sink network. In tropical forest systems and perennial agricultural landscapes, their intact vegetation structure and improved land management regimes enhance soil nutrient cycling, regulate catchment-scale hydrology, stabilize microclimates, and reduce the biophysical impacts of extreme climatic events. These processes enhance the ‘permanence’, reliability, and long-term performance of carbon stocks. As shown in Figure 4 and discussed in [33], such resilience co-benefits, as analyzed from the occurrence of keywords in the scientific literature, including flood attenuation, drought buffering, and stabilization of local agricultural productivity, contribute to reduced reversal risk and strengthen the predictability of mitigation outcomes over time.

Figure 4.

These coupled processes materially influence the permanence, reliability, and long-term performance of carbon stocks. Graphic from [31].

Parallel insights are provided in [34], where it is argued that carbon farming initiatives delivering quantifiable ecological and socio-economic co-benefits are systematically associated with higher market valuations. Co-benefits such as biodiversity enhancement, indigenous land stewardship, improved rangeland condition, and community livelihood gains differentiate these credits within voluntary and compliance markets. The incorporation of these attributes into carbon accounting, monitoring, and certification frameworks enhances environmental integrity and reduces information asymmetries by aligning credit characteristics with emerging buyer expectations around high-integrity, nature-positive outcomes and environmental, social, and governance (ESG)-aligned procurement. Hence, systematic recognition and valuation of co-benefits within carbon market governance can improve price stability, elevate credit prices, and strengthen long-term investor confidence.

By shifting from a tonne-centric valuation paradigm toward a more holistic assessment of ecological and social performance, carbon markets can incentivize integrated land management strategies that simultaneously advance mitigation, resilience, and sustainable development goals at the landscape scale. TFFF and similar mechanisms emerging from COP30 highlight the recognition of carbon sequestration as a tradable and financeable commodity [35,37]. By monetizing verified carbon removal, these initiatives create economic incentives for countries and private stakeholders to protect, restore, and manage tropical ecosystems effectively. Biological carbon sequestration in tropical forests, mangroves, peatlands, and perennial crop systems can thus generate marketable carbon credits while simultaneously delivering co-benefits such as flood-risk mitigation, soil protection, and biodiversity conservation.

The role of carbon sequestration in reducing atmospheric CO2 is both direct and strategic. It provides a natural, scalable, and cost-effective pathway to offset emissions, complementing technological mitigation measures and offering resilience against climate extremes. For many tropical nations, integrating tropical forest conservation and sustainable crop management into carbon credit schemes could enable the simultaneous achievement of climate, economic, and social goals, aligning with global targets articulated during COP30 and operationalized through initiatives like the TFFF [35,37]. Ultimately, carbon sequestration remains a cornerstone in the fight against climate change. Despite occupying only about 12% of the Earth’s land surface, the humid tropics dominate global terrestrial carbon sequestration [40]. Their high net primary productivity, fast growth rates, and dense canopy structures allow these ecosystems to sequester carbon at rates significantly higher than temperate or boreal forests. Wetlands, peatlands, and mangroves, although spatially limited, provide exceptionally high-density carbon storage and serve as long-term carbon reservoirs, particularly critical under scenarios of climate change-induced ecosystem stress. Peatlands, for instance, can store carbon for millennia, and mangrove systems combine carbon sequestration with coastal protection functions, illustrating the multifunctional role of natural carbon sinks.

Forests and agroecosystems regulate hydrological cycles, mitigating both flood and drought risks, improve soil fertility, and provide habitats for biodiversity. Wetlands and riparian buffers contribute to peak-flow reduction, groundwater recharge, and water purification. These services are increasingly recognized as critical for climate adaptation and are now being integrated into measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) frameworks, particularly in the context of TFFF-supported initiatives. Advances in remote sensing, high-resolution LiDAR mapping, drone surveillance, and AI-driven analytics enable precise monitoring of both carbon stocks and co-benefits, ensuring the transparency and credibility of ecosystem-based carbon credits. This facilitates alignment of ecological, social, and financial objectives, creating stronger incentives for governments, private investors, and local communities to participate in ecosystem conservation and sustainable agriculture. The expansion of biological carbon sequestration spatially, functionally, and financially positions tropical ecosystems as a central pillar in achieving global climate stabilization, biodiversity conservation, and climate-resilient development objectives as follows:

Carbon Sequestration Effectiveness

- Tropical forests sequester significantly higher amounts of carbon per hectare per year than temperate and boreal forests.

- Sustainably managed tropical perennial crops (e.g., oil palm, rubber) function as net carbon sinks over their productive lifespans.

- Agroforestry and intercropping systems sequester more total carbon (above- and below-ground) than monoculture plantation systems.

Land Management and Sequestration Enhancement

- 4.

- Improved land management practices (e.g., regenerative farming, soil carbon enhancement, and reforestation) significantly increase carbon sequestration rates compared to conventional practices.

- 5.

- Soil-focused interventions contribute a larger share of long-term carbon permanence than above-ground biomass alone.

3. Significance of Tropical Crops in Carbon Markets

Tropical crops, including perennial trees such as oil palm and rubber, and annual staples such as rice are increasingly recognized not only for their biological carbon sequestration potential but also for their relevance within emerging climate finance architectures. As voluntary and compliance carbon markets evolve, these agricultural systems are becoming eligible for structured crediting schemes that assign monetary value to verifiable mitigation outcomes while maintaining productive land use. Insights from China’s carbon trading pilot policy provide a relevant governance blueprint for accelerating the integration of agricultural systems into carbon markets [41]. Such evidence demonstrates that well-designed carbon-quota allocation mechanisms, particularly those combining free allowances with auctioned quotas, can strengthen firms’ incentives to reduce emissions by tightening marginal abatement cost structures and improving price discovery.

When adapted to agriculture, such quota-based frameworks could reward producers who adopt low-emission cultivation practices, regenerative soil management, methane-reducing rice techniques, and perennial crop replanting strategies that enhance long-term carbon stocks. Moreover, China’s market-incentive model shows that predictable pricing signals, accompanied by transparent monitoring and credit verification rules, stimulate investment in emissions-efficient technologies and encourage sectoral participation at scale [41]. Applying similar incentive structures in tropical agricultural landscapes would not only accelerate the generation of high-integrity carbon credits but also enhance market liquidity, stabilize credit valuation, and promote sustained engagement of farmers, cooperatives, and agribusinesses in carbon mitigation pathways. Such carbon-quota management and market incentives could serve as catalytic instruments for scaling agricultural carbon markets while safeguarding rural livelihoods. TFFF provides a paradigm for linking measurable sequestration outcomes in tropical agroecosystems with long-term investment. TFFF also enables project developers to monetize above- and below-ground biomass and offers co-benefits such as hydrological regulation, biodiversity enhancement, and flood-risk mitigation. For example, riparian oil palm or rubber plantations integrated with buffer strips and wetland corridors can generate additional credits due to their measurable impact on local water retention and extreme-event buffering [36].

As discussed above, recent research has begun to quantify the potential of tropical tree crops to contribute meaningfully to carbon markets to provide sustained, predictable carbon flows suitable for use as investment-backed carbon credits [16]. Rice, while contributing less in above-ground biomass, also enhances soil organic carbon stocks through residues, straw incorporation, and optimized water management, providing an additional avenue for crediting in agricultural MRV frameworks [40]. The inclusion of such staple crops in carbon markets is particularly relevant for Southeast Asia, where smallholder-dominated rice and oil palm/rubber systems represent both a large-scale mitigation potential and opportunities for equitable participation in climate finance. To maximize market participation, methodological advances in measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) have been applied to tropical crops. Remote sensing, UAV-based biomass mapping, and AI-driven crop modeling now allow for near real-time monitoring of plantation carbon stocks, growth dynamics, and associated co-benefits.

The financial structuring of carbon credits from tropical crops is also evolving. Multi-benefit certification labels can differentiate credits from plantations that provide additional ecosystem services, such as flood-risk mitigation in rice paddies or soil stabilization in rubber and oil palm systems. This creates a premium market value, incentivizing sustainable management practices that enhance both carbon sequestration and climate resilience. Integrating smallholders into these frameworks is critical, as they often manage a significant portion of tropical plantations. Benefit-sharing mechanisms, technical support, and capacity-building programs increase the likelihood of long-term adoption and ensure that carbon finance contributes to local socio-economic development [41,42].

Policy integration remains key to advancing tropical crops in carbon markets. Aligning national mitigation targets, agricultural policies, and land-use planning with TFFF and COP30 outcomes can ensure that credits from tropical crops are recognized under internationally transferable mitigation mechanisms. By embedding resilience, biodiversity, and co-benefit metrics into crediting frameworks, tropical crops can deliver comprehensive contributions to climate objectives beyond pure carbon storage. The role of tropical crops in carbon markets is therefore multifaceted: they generate measurable carbon credits, support ecosystem co-benefits, and provide inclusive opportunities for smallholders and local communities. These crops exemplify how productive landscapes can be leveraged as active agents in climate mitigation strategies, with structured carbon finance under COP30-era mechanisms such as TFFF facilitating the scaling of sustainable tropical agriculture while delivering both environmental and socio-economic benefits.

Enhancing biological carbon sequestration in tropical landscapes requires a strategy combining ecological restoration, sustainable agricultural management, innovative land-use planning, and supportive policy frameworks. Research increasingly highlights that carbon sequestration is not solely a function of tree density or crop cover but is influenced by a suite of biophysical, ecological, and socio-economic factors that can be managed and optimized to increase sequestration potential [43,44]. One key measure is the optimization of land management practices in both forested and agricultural systems. For tropical crops and agroforestry landscapes, studies demonstrate that management interventions such as species/variety selection, planting density, canopy structure optimization, intercropping, and rotation schedules directly influence biomass accumulation, root development, and soil organic matter dynamics [45,46]. In agroforestry systems, integrating nitrogen-fixing species and multi-layered vegetation enhances nutrient cycling and soil carbon inputs while improving ecosystem stability [47,48]. Such management approaches are particularly relevant under structured financing mechanisms like TFFF, where measured increases in sequestration can be linked to results-based incentives.

Restoration of degraded and deforested lands is another critical measure to amplify carbon uptake. Systematic reforestation, enrichment planting, and the rehabilitation of riparian zones can improve carbon density over time while enhancing hydrological functions and soil quality [46]. Strategies include prioritizing native species over monocultures to maintain ecosystem resilience, spatially arranging plantings to maximize connectivity, and integrating buffer zones along waterways to enhance both carbon storage and water regulation. By coupling restoration practices with rigorous measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) protocols, these interventions can be quantified and recognized within market mechanisms such as TFFF.

Soil and below-ground management represent a pivotal avenue for increasing sequestration. In tropical ecosystems, soil carbon stocks often exceed the above-ground biomass, and their enhancement requires deliberate interventions. Practices such as organic amendments, cover cropping, conservation tillage, mulching, and residue retention enhance microbial activity, increase soil organic matter, and improve nutrient retention [13]. In agroecosystems, these practices can increase soil carbon stability and resilience to seasonal droughts or flooding, generating co-benefits that complement above-ground sequestration and are recognized under emerging multi-benefit carbon credit frameworks. Hydrological and landscape-level interventions are increasingly recognized for their role in supporting carbon sequestration. Maintaining riparian buffers, integrating wetlands into agricultural landscapes, and implementing water-sensitive land management practices help regulate soil moisture, prevent erosion, and reduce carbon losses [49].

Technological and monitoring approaches are also essential for guiding sequestration measures. Advances in remote sensing, LiDAR, high-resolution satellite imagery, and AI-driven ecological modeling enable the identification of underperforming areas, measurement of biomass accumulation, and estimation of soil carbon dynamics with high spatial and temporal resolution [50]. These tools inform targeted interventions, adaptive management, and verification protocols necessary for structured results-based carbon financing, including TFFF crediting. Policy, institutional, and financial mechanisms also play a central role in promoting the adoption of high-sequestration measures. Incentive schemes, capacity-building programs for smallholders, and integration of sequestration measures into national climate strategies encourage uptake at scale [36,51]. Structuring payments based on verified outcomes as in TFFF aligns economic benefits with ecological objectives, ensuring that investments are directed towards enhancing carbon storage while delivering co-benefits such as biodiversity, hydrological regulation, and climate resilience.

Community engagement and participatory governance are fundamental to the success of sequestration measures. Research consistently demonstrates that locally managed forests and crop systems with active stakeholder participation exhibit higher rates of carbon retention, improved ecosystem health, and sustainable long-term outcomes. Empowering communities through knowledge transfer, shared monitoring responsibilities, and benefit-sharing agreements ensures that sequestration measures are maintained over time, creating durable impacts that reinforce both ecological and social resilience. Results-based payment schemes remain central to promoting adoption, particularly those linked to verified carbon sequestration outcomes in tropical forests, agroforestry, and high-carbon crops such as oil palm, rubber, and rice. TFFF, for example, represents a structured mechanism to channel predictable public and private investment into countries and regions that demonstrate measurable carbon retention, restoration, or improved management, thereby reducing the risk of deforestation and degradation while encouraging sustainable land use [16,21].

Market-based instruments, including voluntary carbon credits and compliance-linked offsets, provide further incentives. Structuring credits to reflect multiple ecosystem services carbon storage, biodiversity conservation, and hydrological regulation enhances both environmental integrity and economic value, making carbon-friendly practices more attractive to investors [43]. Tiered crediting approaches, where projects demonstrating co-benefits such as flood mitigation or soil carbon accumulation receive higher remuneration, have been shown to stimulate uptake of regenerative management practices across tropical agricultural landscapes [33]. Institutional mechanisms play a critical role in enabling adoption. Access to technical assistance, extension services, and knowledge transfer on improved crop management, soil carbon enhancement, and agroforestry design is crucial, particularly for smallholder farmers who lack capital and relevant expertise [36,52].

Secure land tenure, participatory governance, and transparent verification procedures further incentivize stakeholders by providing confidence that their investments in sustainable practices will be recognized and compensated [36]. Public–private partnerships (PPPs) have proven effective in scaling adoption; for example, by linking government programs, multinational corporations, and local cooperatives, they can provide both financial and technical support for project implementation while enabling aggregation of smallholder plots into standardized, MRV-compliant units suitable for carbon credit markets [42]. This approach not only enhances the economic feasibility of sequestration projects but also allows carbon markets to operate at larger spatial scales, improving efficiency and credibility and addressing concerns about so-called ‘greenwashing’.

Integration of new technologies into MRV systems reduces uncertainty, transaction costs, and implementation risks for both large plantations and smallholder farms [53]. Digital monitoring can significantly improve credit verification and investor confidence, especially when co-benefits such as flood mitigation or erosion control are included [33,34]. Policy frameworks are crucial to reinforce these mechanisms. Incentives such as subsidies for sustainable crop management, tax reductions for agroforestry adoption, and regulatory recognition of ecosystem service contributions can accelerate uptake. Importantly, integrating adaptation co-benefits such as flood mitigation, improved soil water retention, and drought resilience into carbon credit methodologies has been highlighted as priorities in tropical contexts, aligning local ecosystem management with broader climate resilience objectives [33,54].

Social mechanisms complement financial and technological measures by ensuring long-term stewardship and local participation. Community engagement, participatory monitoring, and benefit-sharing arrangements strengthen legitimacy and compliance while enhancing local livelihoods [55,56]. Incorporating traditional knowledge into land management and carbon project design has also been shown to improve ecosystem function and adoption success in smallholder-dominated tropical landscapes [57]. Collectively, these mechanisms demonstrate that effective adoption of enhanced biological carbon sequestration is contingent on integrating finance, policy, technology, and community engagement. By recognizing carbon storage alongside co-benefits, such as biodiversity conservation and flood mitigation, stakeholders are incentivized to implement high-carbon practices across diverse tropical ecosystems, including oil palm, rubber, and other high-biomass perennial crops such as cocoa. Some ecosystem co-benefits are listed below.

Ecosystem Co-benefits and Carbon Integrity

- Carbon projects that deliver measurable ecosystem co-benefits (flood mitigation, drought buffering, biodiversity) exhibit lower carbon reversal risk than projects focused solely on carbon storage.

- Carbon credits incorporating independently verified ecosystem and social co-benefits are less likely to be associated with ‘greenwashing’ allegations than carbon-only credits.

- Carbon projects with formal community participation and benefit-sharing mechanisms demonstrate higher carbon permanence than projects without such mechanisms.

- Carbon projects that integrate high-integrity MRV with enforceable community rights protections have lower ‘greenwashing’ risk and higher long-term carbon permanence.

4. The Development of Carbon Markets

Historically, carbon markets have evolved through compliance mechanisms, voluntary credit schemes, and, increasingly, land-use and forest-based offsets, such as avoided deforestation, reforestation, afforestation, sustainable forestry, and agroforestry. This evolution reflects growing scientific understanding of biological carbon sequestration [1,58] and shifting climate finance priorities under global frameworks such as COP30 [59]. However, the establishment and regulation of fully transparent and sustainable carbon trading schemes that are appropriate for local populations, and not mere ‘greenwashing’, remains a significant challenge [60,61]. Initial carbon trading efforts, including cap-and-trade and emissions allowance systems, primarily focused on industrial emissions. For example, the Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX), launched in 2003, was a voluntary but legally binding trading system that allowed companies to meet part of their commitments through offsets, including land-use, forestry, and soil carbon projects [62,63]. By demonstrating that ecosystem-based carbon sinks could be converted into tradable financial assets, CCX provided an early model for integrating biological sequestration into markets. However, by 2010, structural weaknesses, oversupply of offset credits, stagnant demand, and collapsing prices eventually led to its demise [63]. This highlights challenges such as environmental integrity, robust baselines, additionality, permanence, and credible market demand [64].

Early regulatory frameworks, such as the initial phases of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, largely underrepresented forestry and land-use credits due to measurement, verification, and permanence complexities [65]. This gap prompted advocacy initiatives, such as the Global Canopy Programme ‘Forests Now’ Declaration, which argued for including avoided deforestation and forest-protection credits to prevent CO2 releases from tropical forests [66]. Between 2006 and 2015, forestry and land-use (LULUF) credits avoided deforestation/forest conservation (REDD+ style) expanded rapidly in issuance volume. A recent decomposition analysis found that the increase in forestry-related credits was largely driven by both greater priority being given to REDD+ projects and scale expansion across regions [67]. This growth underpinned what many saw as a scalable, cost-effective way to harness nature-based carbon sinks, particularly tropical forests and other high-productivity ecosystems as discussed above. In many tropical regions, such as Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Africa, forest credits became among the primary supply of carbon offsets to global buyers.

The rapid expansion of forestry and REDD+ carbon credits from 2005 to 2015 was followed by a pronounced erosion of market confidence, driven by well-documented integrity concerns, including inflated baselines, leakage, non-permanence risks, and weak governance structures. These shortcomings contributed to the contraction of voluntary carbon markets in 2022–2023 and underscore the reputational and financial risks of low-integrity offsetting practices. In response, recent advances in remote sensing, machine learning, and digital measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) systems have substantially enhanced transparency, accuracy, and traceability. These innovations enable more credible accounting of additionality and permanence, supporting a market reorientation toward high-integrity, landscape-scale, and multi-benefit carbon projects that are less vulnerable to ‘greenwashing’ claims.

Within this context, forestry-based carbon credits have regained traction in both compliance and voluntary markets, in part because they can offer relatively low-cost abatement compared to certain industrial mitigation options. However, their legitimacy increasingly depends on rigorous MRV, conservative baselines, long-term stewardship mechanisms, and demonstrable social and biodiversity co-benefits, rather than price competitiveness alone. Empirical evidence indicates that corporate buyers exhibit heterogeneous price sensitivities and purchasing behaviors across carbon project types. Some buyers demonstrate a willingness to pay premiums for higher-integrity projects, while others prioritize lower-cost options aligned with efficiency-driven carbon management strategies.

Statistical t-test results further indicate that corporate motivations such as carbon management, organizational values, or market competitiveness significantly influence both the volume and type of carbon projects and standards purchased. Firms motivated by values and reputational considerations tend to favor higher-quality (and often higher-priced) standards associated with stronger co-benefits and credibility, whereas firms primarily focused on cost-efficient carbon management gravitate toward lower-priced options. These findings highlight that corporate offset purchasing is not value-neutral: without clear integrity thresholds and transparent disclosure, reliance on low-cost credits risks perpetuating ‘greenwashing’, whereas alignment between motivation, project quality, and verification rigor is critical to ensuring credible climate claims [68].

By the late 2010s and into the 2020s, a growing body of research, media investigations, and market analyses revealed serious challenges tied to forest-based carbon credits, especially those tied to avoided deforestation and/or forest conservation. Problems ranged from flawed baselines (i.e., overestimating counterfactual deforestation), weak additionality (projects claiming to prevent deforestation that may not have occurred), permanence concerns (fire, logging, degradation), leakage (deforestation migrating elsewhere), to weak governance and lack of community safeguards. Such concerns have led to declining trust and demand in certain segments of the carbon market as recently highlighted [60,61]. Between 2022 and 2023, voluntary carbon markets contracted, with a 56% decline in reported transactions and a substantial drop in forestry/REDD+ credit values and volumes. This contraction reflected both market fatigue and increased scrutiny of credit quality. As price and demand fell, many forest-based projects, especially those relying on avoided deforestation with unclear baselines, lost profitability and investor interest.

Against this backdrop, advances in remote sensing, machine learning, and high-resolution aerial or satellite imagery have offered new tools to improve the measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) of carbon stocks and land-use changes, helping to overcome many of the historical challenges. For example, the dataset and methodology developed in the ReforesTree project demonstrate that deep-learning models applied to drone imagery can estimate tropical forest carbon stock with greater accuracy and lower cost than traditional field-based inventories, making scalable forest biomass and carbon stock assessment feasible for offset and credit programs [69]. Similarly, region-level reviews, such as the recent assessment of forest carbon markets in Latin America, highlight the potential of remote sensing to reduce technical barriers to MRV, improving credibility and enabling expansion of high-quality forest carbon credits. These methodological improvements resonate with earlier sections on the global scope of biological carbon sequestration and the need for robust MRV mechanisms in adoption. By enhancing transparency and reducing uncertainty, they enable a re-imagined carbon market architecture that better matches ecological realities with financial incentives.

More recently, the critique of legacy forest credit systems focused narrowly on carbon has catalyzed a shift toward market models that value multiple ecosystem services beyond CO2 removal, including biodiversity conservation, hydrological regulation, soil protection, community livelihoods, and climate adaptation. This reflects the broader perspective developed in earlier sections (e.g., significance of ecosystem co-benefits from tropical forests and crops, measures to increase sequestration, adoption mechanisms, etc.). Studies and market analyses published in 2023–2025 show increasing interest in ‘AFOLU credits’ that combine carbon with other ecosystem services [70], raising their appeal to investors seeking aligned ESG, biodiversity, or resilience benefits beyond carbon accounting. This transition aligns with ongoing policy developments (e.g., under COP30-era frameworks), which emphasize integrated landscape stewardship, inclusion of agroecosystems and crops, and co-benefit-based financing mechanisms like TFFF. By embedding biodiversity, water regulation, and social impacts into crediting standards, carbon markets evolve from mere offsetting instruments into holistic tools for sustainable land-use, climate mitigation, and adaptation.

The historical experience of carbon market successes, failures, and recent recalibrations offers several important lessons relevant to the current push for large-scale tropical forest and crop-based sequestration. Integrity and verification matter. Early enthusiasm for forest-based offsets was often undermined by weak baselines, poor accounting, and governance shortcomings. Emerging MRV technologies and stricter standards are necessary to ensure that real, additional, and long-term carbon removal echoes the need for rigorous measurement. Flexibility and adaptation are also key factors. Markets evolved from industrial emissions trading to voluntary carbon credits, REDD+, mixed AFOLU credits, and now toward multi-benefit, landscape-based instruments. This flexibility allows the incorporation of new scientific understanding (e.g., on soil carbon, crop sequestration, and co-benefits) to align market design with ecological complexity.

Scaling requires credible finance and institutional support. Broad adoption of sequestration measures depends on predictable and transparent financing as envisioned in mechanisms like TFFF alongside supportive policy, governance, and community engagement. Market demand must align with environmental integrity. Oversupply of low-quality or non-additional credits undermines both market value and climate goals. Historical contraction of forestry credits post-2022 shows that without credibility, demand collapses. Ecosystem co-benefits also increase value and resilience. Carbon markets focused solely on CO2 storage may miss broader ecological and social benefits. History shows that markets evolving toward multi-service valuation including biodiversity, hydrology, soil health, and livelihoods are better aligned with sustainable development, climate adaptation, and long-term ecosystem stewardship.

As the world enters the post-COP30 era in 2026, carbon markets are at a critical juncture. The launch of TFFF, renewed interest in tropical forests and agroecosystems, and scientific advances in MRV and ecosystem service quantification all draw directly on the lessons of history. The evolution of markets suggests that credible, high-integrity, multi-benefit carbon credits that integrate sequestration from forests, tropical crops, soils, and hydrological services may form the backbone of future international climate finance mechanisms. As outlined in Figure 5, mechanisms that stimulate adoption include jurisdictional REDD+ frameworks, voluntary carbon market participation, green supply chain financing, and benefit-sharing agreements that align community interests with climate objectives [33,34]. Secure land tenure, transparent monitoring, and supportive institutional environments further enhance the likelihood of uptake and long-term participation.

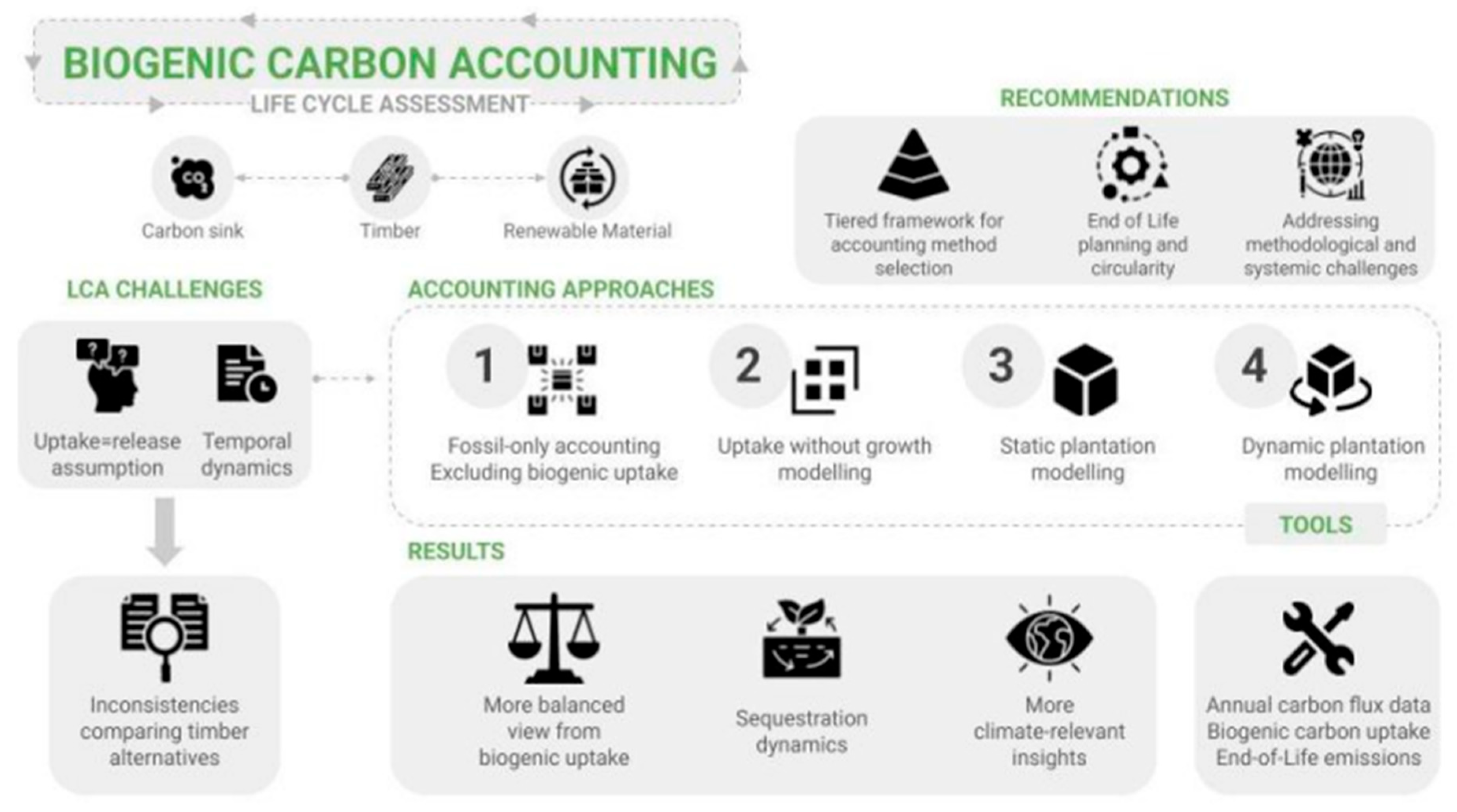

Figure 5.

Addressing key methodological and system-level constraints, the research facilitates consistent supply chain carbon accounting frameworks and underpins sustainable material choices within forestry and the built environment. Graphic from [27].

By learning from past shortcomings, leveraging technological and methodological advancements, and designing incentives that value not only carbon but ecological resilience and social equity, carbon markets can support large-scale biological carbon sequestration aligned with global climate, biodiversity, and development goals. Some positive and negative linkages between carbon market valuation and demand include the following: (i). Carbon credits associated with verified ecosystem co-benefits command higher market prices than carbon-only credits. (ii). Corporate buyers motivated by ESG values and reputational considerations prefer higher-integrity, higher-priced carbon credits over lower-cost alternatives. (iii). Firms that are primarily motivated by cost efficiency are more likely to purchase lower-priced carbon credits with fewer co-benefits.

5. New Approaches to More Effective Unified Regional and Global Carbon Markets

Emerging approaches aim to unify fragmented carbon markets and enhance effectiveness through digital MRV using satellite and AI systems, blockchain-based credit traceability, interoperable registries, and sectoral methodologies aligned with Article 6 of the 2015 Paris Agreement [42]. In 2025, COP30 discussions emphasized integrating tropical ecosystems to ensure credible accounting of carbon and co-benefits, including adaptation outcomes such as flood-risk mitigation. Linking regional and global markets, harmonizing standards, and recognizing ecosystem services beyond carbon can scale up mitigation finance, enhance resilience, and incentivize sustainable forest and crop management. The TFFF scheme exemplifies a transformative approach by embedding nature-based carbon sequestration within a results-oriented financial architecture [35,36,37]. Long-term, performance-based funding rewards verified conservation and restoration of tropical forests, wetlands, and agroforestry systems, ensuring credits reflect real, additional, and permanent sequestration. Incorporating co-benefits such as flood-risk mitigation, biodiversity protection, and soil stabilization creates new carbon products with higher market value, attracting private capital, green bonds, and sustainability-linked financing.

Technological innovations further enhance market effectiveness. Digital MRV platforms leveraging satellite imagery, LiDAR, and AI enable near-real-time monitoring of carbon stocks and ecosystem health, allowing dynamic valuation of co-benefits including hydrological regulation, disaster-risk reduction, and community resilience. Blockchain-based registries and interoperable credit systems improve traceability, prevent double-counting, and standardize accounting across national and voluntary markets. Sectoral and regional integration aligning REDD+ programs, voluntary markets, and TFFF-backed instruments reduces fragmentation, encourages smallholder participation, and enhances liquidity. Regarding measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV), two major points can be made: (i). The adoption of advanced MRV technologies (AI, remote sensing, LiDAR) significantly reduces uncertainty in carbon stock estimates. (ii). Carbon projects using digital MRV systems demonstrate higher investor confidence than projects relying on traditional field-based monitoring.

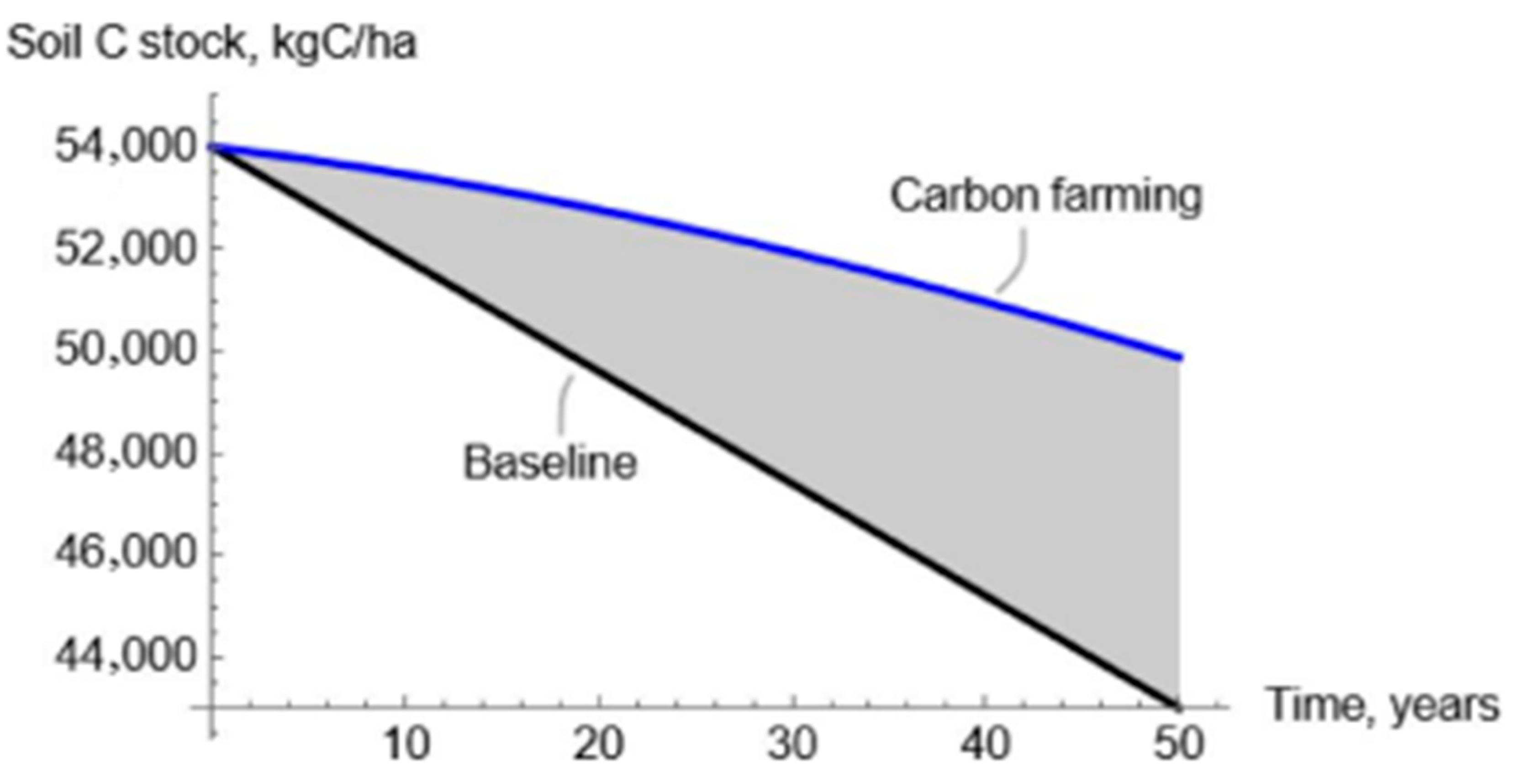

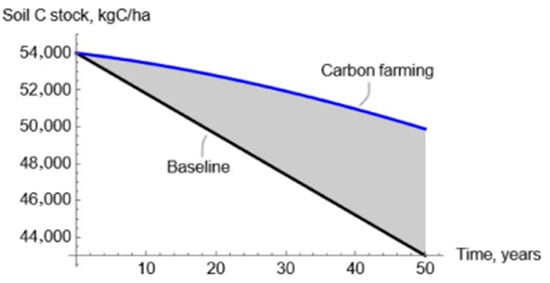

Hydrological resilience, including flood-risk mitigation and seasonal drought buffering, is increasingly recognized as a critical co-benefit. Tropical forests, mangroves, peatlands, riparian buffers, and agroforestry systems regulate water, reducing flood intensity and maintaining soil moisture during dry periods. Standardized metrics for canopy structure, soil organic content, root density, and surface roughness now enable quantification of hydrological contributions across seasons. Coastal ecosystems like mangroves and tidal wetlands can be assessed for storm-surge attenuation and water retention, providing the technical foundation for credible verification alongside carbon sequestration. Carbon projects that deliver measurable ecosystem co-benefits (flood mitigation, drought buffering, biodiversity) exhibit lower carbon reversal risk than projects focused solely on carbon storage. Inclusion of hydrological regulation metrics significantly improves the long-term reliability of carbon sequestration outcomes. Permanence remains a key design consideration for soil and agricultural carbon initiatives, where stored carbon is vulnerable to reversal. Temporary, renewable credits offer a flexible mechanism to reward carbon farming practices while transparently accounting for reversibility [45]. As shown in Figure 6, the additional benefit from carbon farming is represented by the shaded area between the baseline and carbon farming curves [71].

Figure 6.

Example of the potential evolution of the soil C stock in a baseline scenario and with a carbon farming practice. The additional benefit from carbon farming is represented by the shaded area between the baseline and the carbon farming curves. Graphic from [71].

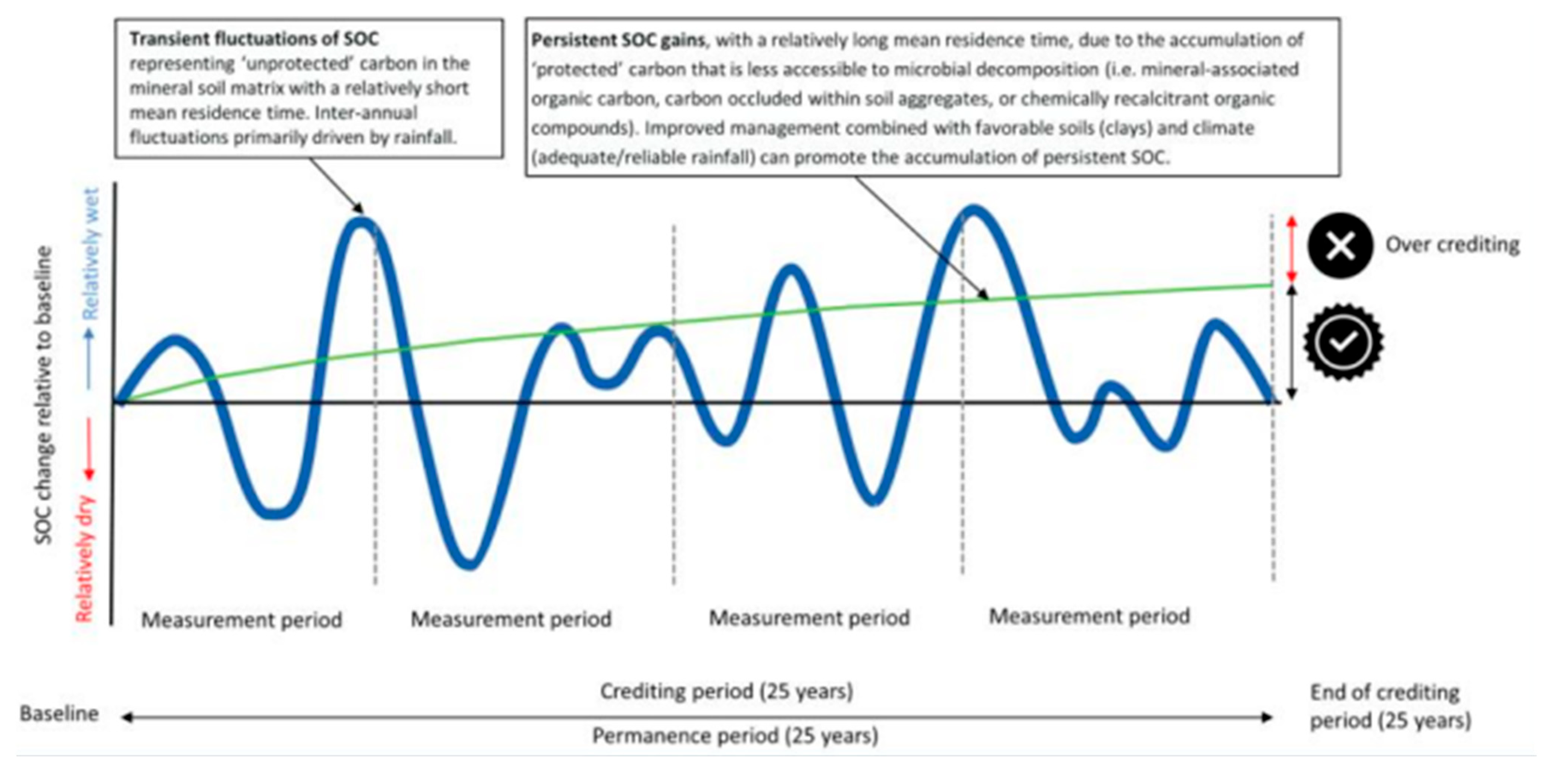

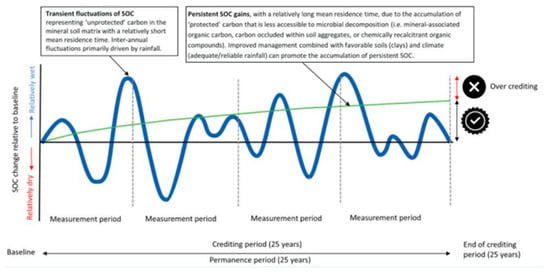

As illustrated in Figure 7, integrating temporary crediting with hydrological metrics gives carbon gains and improvements in seasonal water retention, flood mitigation, and soil moisture stability [71].

Figure 7.

A conceptual diagram of ‘new’ carbon entering the soil system over a 25-year crediting period. Transient fluxes of SOC (blue) versus the accumulation of more persistent SOC. Graphic from [71].

Future carbon markets could introduce resilience premiums or multi-benefit certification labels to differentiate credits generated by ecosystems with substantial hydrological contributions. The Article 6.2 and 6.4 enhancements from the Paris Agreement allow adaptation co-benefits to be recognized in internationally transferred mitigation outcomes [60]. This approach encourages investment in ecosystems that deliver both carbon sequestration and disaster-risk reduction, particularly in tropical regions exposed to floods and seasonal droughts. Alignment with emerging standards such as the EU Carbon Removal Certification Framework (CRCF) further strengthens environmental integrity [72]. CRCF criteria cover additionality, long-term storage, and sustainability safeguards and distinguish temporary from permanent removals [73]. Co-benefit assessments such as biodiversity, soil health, and water regulation are integrated into certification rules. Applying CRCF-aligned protocols to hydrology-based carbon frameworks ensures recognition of flood attenuation and drought buffering as quantifiable benefits, enhancing compatibility with international compliance and voluntary markets.

Expanding project eligibility to include hydrologically important ecosystems such as mangroves, peat swamps, floodplain forests, and riparian corridors supports landscape-level strategies that optimize carbon and water regulation. Hydrological resilience as a co-benefit represents a logical evolution of climate-related NbS. Financial mechanisms such as green bonds, sustainability-linked loans, and blended finance can incentivize projects that reduce flood exposure and maintain water availability during dry seasons. Community involvement is essential for long-term ecosystem stewardship. Benefit-sharing, livelihood incentives, and community-centered monitoring strengthen local participation and ensure equitable distribution of resilience benefits. Historically, mechanisms such as CDM, early voluntary standards, and REDD+ laid the foundation for NbS. Recently strengthened quality standards, governance, and collaborative models have renewed confidence in carbon markets. Strategic alliances leverage complementary resources, generate cross-sectoral synergies, foster innovation, and expand market reach, enhancing credit quality, liquidity, and scalability [43].

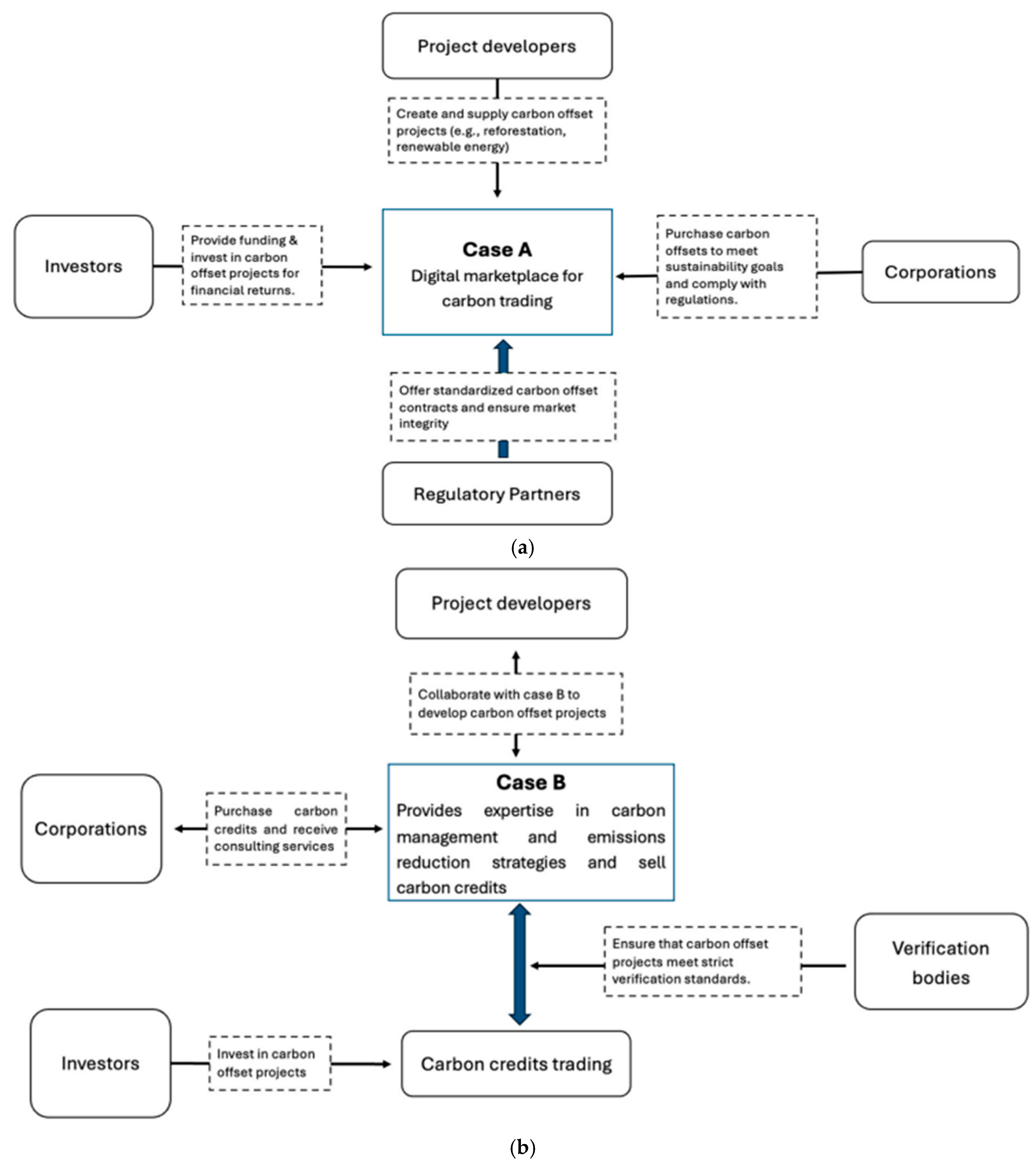

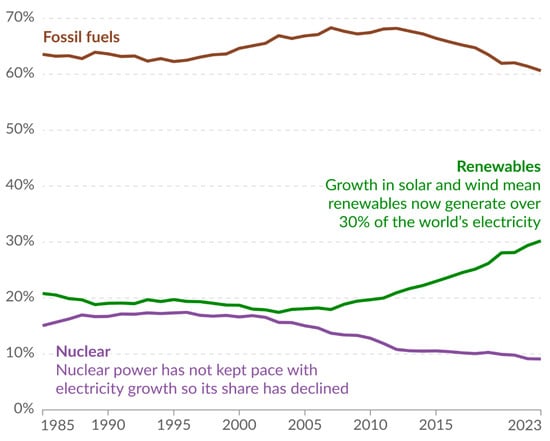

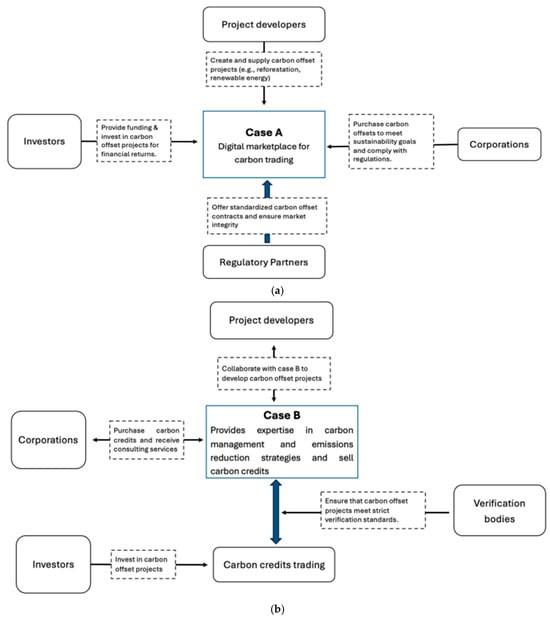

As shown below in Figure 8, Case A and Case B collaborative resource sharing enhances institutional capacity and credit quality. Case A’s partnership model pools technological and financial resources with business partners to develop standardized carbon-offset contracts, thereby stabilizing market infrastructure and reducing transaction uncertainties. Case B’s collaborations with project developers and corporate actors facilitate access to diverse project portfolios and technical expertise, enabling the development of high-integrity credits and strengthening its overall project pipeline. As one Case B representative noted, accessing partner expertise “strengthens our overall offerings”. Case B’s additional joint ventures with investors further illustrate how financial and technical complementarities enable the execution of large-scale mitigation projects with substantial emission-reduction potential [43].

Figure 8.

(a) Case A operation narrative showing a digital marketplace for carbon trading. Graphic from [43]. (b) Case B operation narrative which provides expertise in carbon management strategies, emissions reduction strategies, and sales of carbon credits. Graphic from [43].

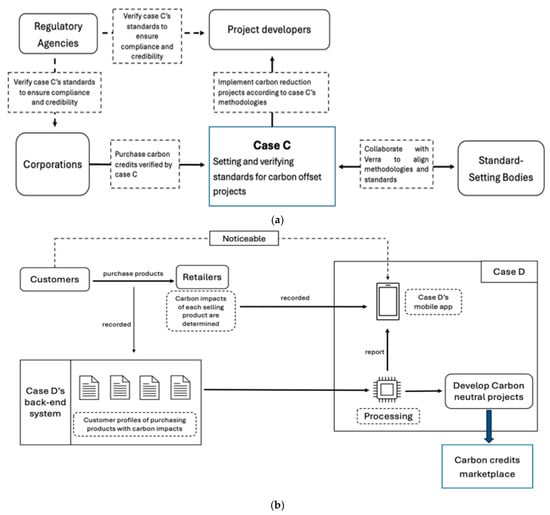

Case C in Figure 9 and Case A in Figure 8 show the value of integrating distributed initiatives within coherent governance structures. Case C creates systemic synergies by consolidating heterogeneous carbon-reduction projects under unified standards to ensure methodological consistency and enhance environmental impact. Case A, through its digital marketplace model, generates multi-stakeholder synergies by connecting developers, investors, and buyers within a single transactional ecosystem. This platform brings together diverse stakeholders, creating synergies that enhance the overall effectiveness of carbon trading.

Figure 9.

(a) Case C operation narrative—setting and verifying standards for carbon offset projects. Graphic from [43]. (b) Case D operation narrative—agroforest and agriculture have considerable commercial use by extending bioeconomy. Graphic from [43].

Case B and Case D in Figure 9b show how cross-sector collaborations can catalyze innovative carbon-offsetting modalities and methodological advancements. Case D’s partnership with retailers introduces novel mechanisms for embedding carbon-offset contributions into routine consumer purchases, expanding public participation and normalizing carbon-positive behaviors. Case B’s collaboration with project developers similarly drives methodological innovations, producing more robust and verifiable carbon-crediting approaches. These innovations enhance the quality and effectiveness of carbon credits.

Market expansion strategies across cases A to D illustrate the importance of international visibility and diversified engagement channels. Case A leverages partnerships with major corporations and investors to increase its market penetration and influence. Case B expands its geographical footprint by participating in multiple carbon exchanges, thereby accessing broader project pipelines and a more diverse buyer base (B1). Case C institutionalizes global outreach by collaborating with international organizations and participating in global standard-setting forums. Case D likewise broadens its reach by partnering with international retailers, promoting carbon-offsetting opportunities to consumers worldwide, thereby amplifying global impact.

The four cases A to D implicitly represent increasing levels of project integrity and governance maturity, as summarized below in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the characteristics and key risks as described in detail in the study in ref [43].

Carbon projects structured under the Case D management frameworks exhibit significantly lower ‘greenwashing’ risk than projects implemented under Case A, B, or C frameworks. The level of transparency and MRV rigor increases systematically from Case A to Case D project frameworks, resulting in progressively higher carbon credit credibility. The Case C and Case D frameworks demonstrate higher long-term carbon permanence than Case A and Case B projects due to formalized community participation mechanisms. Projects under Case D frameworks, which incorporate enforceable benefit-sharing arrangements, experience fewer land-use conflicts and lower carbon reversal risks than Case A–C projects. The positive effect of carbon finance on sequestration outcomes is stronger in the Case C and D frameworks, where land tenure and community rights are explicitly recognized. Carbon project management frameworks progress from high ‘greenwashing’ risk and low social legitimacy in Case A to low ‘greenwashing’ risk and high social legitimacy in Case D. In terms of market valuation, carbon credits generated under Case D frameworks command higher and more stable market prices than credits from Case A, B, or C frameworks.

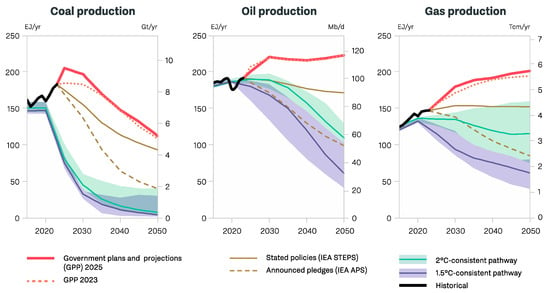

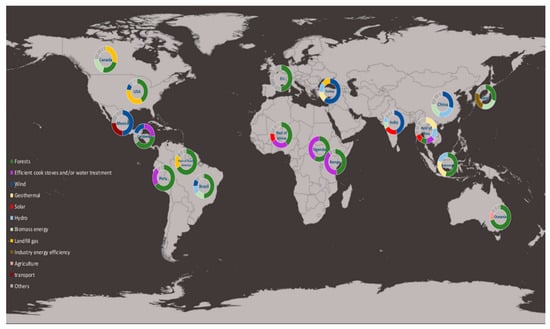

Cases A to D demonstrate that collaborative mechanisms directly enhance carbon market performance by improving credit quality, strengthening governance structures, reducing informational asymmetries, and expanding participation [43]. In developing-country contexts where regulatory fragmentation and capacity gaps persist, these partnership models play an indispensable role in shaping credible, scalable, and resilient carbon trading systems, as demonstrated in the global distribution map shown in Figure 10. The Cases collectively affirm that strategic partnerships are foundational to the emergence of high-integrity carbon markets capable of supporting long-term mitigation and sustainable-development goals [69].

Figure 10.

Global distribution of carbon voluntary offset project types showing that there may be gaps in the types of benefits accruing in places that need them. Graphic from [70].

New approaches are emerging to create unified and more effective regional and global carbon markets. These include digital MRV using satellite-AI systems, interoperable registries, blockchain-based credit traceability, sectoral crediting methodologies, and alignment of voluntary market standards with Article 6 of the Paris Agreement [42]. If adopted, the measures agreed to at COP30 in 2025 should accelerate the integration of tropical ecosystems into global carbon market architectures, potentially transforming how tropical forests and perennial tree crops are valued in climate finance systems. These innovations aim to address persistent challenges such as double-counting, fragmented standards, limited smallholder participation, and inconsistent quality among credits.

6. Conclusions

In 2025, the IPCC limit of a 1.5 °C rise in average global temperatures was exceeded for the second successive year, and evidence continues to mount of the increasingly erratic climatic consequences across the planet [74]. Notwithstanding several decades of discussions on mechanisms to reduce CO2 and other GHG emissions, these continue to rise, and, in many cases, previously agreed mitigation targets have been postponed or even abandoned. These recent developments highlight the importance of increasing the rate of CO2 removal from the atmosphere via global-scale carbon sequestration. Over recent decades there has been much investment in experimental engineering approaches such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) and direct air capture and storage (DACS) [8]. However, it is now clear that such strategies are unlikely to deliver reliable carbon sequestration at the gigatonne scale before the end of the century [75,76,77].

The alternative approach suggested here is to deploy nature-based strategies that ultimately rely on enhancing the proven biological process of oxygenic photosynthesis that has already been delivering gigatonne-scale carbon sequestration at global scale for over two billion years [78]. In particular, there is considerable scope for further enhancing the carbon sequestration performance of high-yield terrestrial vegetation and especially tropical forests and perennial crops via enhanced strategies for sustainable land management [79]. Such strategies include reforestation and afforestation programs, agroforestry integration, regenerative soil management, and sustainable intensification practices that boost both productivity and carbon storage [19,20]. In order to achieve these challenging goals, we have analyzed the transformative potential of emerging next-generation carbon markets to unlock enhanced carbon sequestration at a truly global scale.

We show that many of the earlier approaches were characterized by insufficient monitoring capabilities, especially in developing countries, and ultimately failed due to factors such as carbon credit fraud. Moving forward, the challenges for successful policy implementation of global-scale carbon trading must be recognized (as analyzed in depth in Figure 9, Table 1, and the accompanying discussion). Some of the key elements include enforceable benefit-sharing arrangements, formalized community participation and benefit-sharing mechanisms, higher long-term carbon permanence, and results-based financing mechanisms (e.g., TFFF-type models). One of the most important prerequisites for success is complete transparency at all stages of the carbon trading process, which will be greatly facilitated by the deployment of new tools such as real-time publicly verifiable imaging and the availability of reliable and independently measured carbon performance data based on field measurements. The participation of social actors, including private and public sector entities, communities, and monitoring bodies, will also mitigate the risk of ‘greenwashing’ allegations that have been commonplace in many previous initiatives.

We have also critically assessed the contributions of tropical ecosystems to carbon sequestration and evaluated the emerging carbon trading approaches that could strengthen climate and economic outcomes in tropical regions. Given the recent setbacks in achieving climate goals based on emissions reductions [3,4,5,6], the unlocking of the global potential of nature-based carbon sequestration merits further analysis and hopefully implementation. It has been estimated that such a harnessing of terrestrial ecosystems and agroecosystems could enable an additional carbon capacity of 367 Gt C capture by the end of the 21st century, with a possible reduction in atmospheric CO2 levels by as much as 156 ppm [71]. There are formidable challenges before such aspirations can be met, especially as they will require an open-minded and realistic commitment from governments, companies, and civil society groups across the world to work collaboratively. Such global cooperation will be essential to achieve these goals in order to mitigate one of the most serious threats to the future of our complex and interlinked technological civilizations.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the planning and carrying out of this research, including data analysis, writing the manuscript, and responding to reviewers’ comments. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data derived from public domain resources.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the valuable discussions with and feedback from numerous colleagues during the genesis of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Murphy, D.J. Biological Carbon Sequestration: From Deep History to the Present Day. Earth 2024, 5, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ember, E. Statistical Review of World Energy. 2024. Available online: https://ember-energy.org/app/uploads/2024/05/Report-Global-Electricity-Review-2024.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2026).

- Climate Action Tracker. Warming Projections Global Update. November 2025. Available online: https://climateactiontracker.org/documents/1348/CAT_2025-11-13_GlobalUpdate_COP30.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2026).

- Global Energy Review. 2025. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/5b169aa1-bc88-4c96-b828-aaa50406ba80/GlobalEnergyReview2025.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2026).

- SEI; Climate Analytics; IISD. The Production Gap Report 2025; Stockholm Environment Institute: Stockholm, Sweden; Climate Analytics: Berlin, Germany; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2025; Available online: http://productiongap.org/2025report (accessed on 30 January 2026).

- European Commission. Copernicus: 2025 on Course to be Joint-Second Warmest Year, with November Third-Warmest on Record. 9 December 2025. Available online: https://climate.copernicus.eu/copernicus-2025-course-be-joint-second-warmest-year-november-third-warmest-record (accessed on 30 January 2026).

- United Nations Environment Programme. Emissions Gap Report 2025: Off Target–Continued Collective Inaction Puts Global Temperature Goal at Risk; Olhoff, A., Lamb, W., Kuramochi, T., Rogelj, J., den Elzen, M., Christensen, J., Fransen, T., Pathak, M., Tong, D., Eds.; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2025; Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/rest/api/core/bitstreams/4830e1a8-14c0-44a5-a066-cdd2ba5b3e10/content (accessed on 30 January 2026).

- Murphy, D.J. Carbon Sequestration for Global-Scale Climate Change Mitigation: Overview of Strategies Plus Enhanced Roles for Perennial Crops. Crops 2025, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA. The Relentless Rise of Carbon Dioxide. 2024. Available online: https://tiny.cc/yavh001 (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- Nayak, N.; Mehrotra, R.; Mehrotra, S.S. Carbon biosequestration strategies: A review. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2022, 4, 1000065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Zhou, H.; Cao, Y.; Liao, H.; Lu, X.; Yu, Z.; Yuan, W.; Liu, Z.; Lei, Y.; Sitch, S.; et al. Large Potential of Strengthening the Land Carbon Sink in China through Anthropogenic Interventions. Sci. Bull. 2024, 69, 2622–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akita, N.; Ohe, Y. Sustainable Forest Management Evaluation Using Carbon Credits: From Production to Environmental Forests. Forests 2021, 12, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrar, M.M.; Waqas, M.A.; Mehmood, K.; Fan, R.; Memon, M.S.; Khan, M.A.; Siddique, N.; Xu, M.; Du, J. Organic Carbon Sequestration in Global Croplands: Evidenced through a Bibliometric Approach. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1495991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhyani, S.; Murthy, I.K.; Kadaverugu, R.; Dasgupta, R.; Kumar, M.; Gadpayle, K.A. Agroforestry to Achieve Global Climate Adaptation and Mitigation Targets: Are South Asian Countries Sufficiently Prepared? Forests 2021, 12, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruml, A.; Chen, C.; Kubitza, C.; Kernecker, M.; Grossart, H.P.; Hoffmann, M.; Holz, M.; Wessjohann, L.A.; Lotze-Campen, H.; Dubbert, M. Minimizing Trade-Offs and Maximizing Synergies for a Just Bioeconomy Transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 125, 104089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassary, E.K. Exploring the Role of Nature-Based Solutions and Emerging Technologies in Advancing Circular and Sustainable Agriculture: An Opinionated Review for Environmental Resilience. Clean. Circ. Bioecon. 2025, 10, 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameray, A.; Bergeron, Y.; Valeria, O.; Montoro Girona, M.; Cavard, X. Forest Carbon Management: A Review of Silvicultural Practices and Management Strategies across Boreal, Temperate, and Tropical Forests. Curr. For. Rep. 2021, 7, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.J. Carbon Sequestration by Tropical Trees and Crops: A Case Study of Oil Palm. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutika, L.-S. Boosting C Sequestration and Land Restoration through Forest Management in Tropical Ecosystems: A Mini-Review. Ecologies 2022, 3, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, S.; Chavan, S.B.; Chichaghare, A.R.; Uthappa, A.R.; Kumar, M.; Kakade, V.; Pradhan, A.; Jinger, D.; Rawale, G.; Yadav, D.K.; et al. Agroforestry Systems for Soil Health Improvement and Maintenance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Zhu, J.; Xu, L.; He, N. Technological Approaches to Enhance Ecosystem Carbon Sink in China: Nature-Based Solutions. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2022, 37, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu-Dias, R.; Santos-Gago, J.M.; Martín-Rodríguez, F.; Álvarez-Sabucedo, L.M. Advances in the Automated Identification of Individual Tree Species: A Systematic Review of Drone- and AI-Based Methods in Forest Environments. Technologies 2025, 13, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiarto, R.; Dewanto, B.G. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for Assessing Biomass and Carbon Stocks in Mangrove Forests: A Systematic Review. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 101425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.R.; Grima, N.; Belohrad, V.; Fisher, B. Options for Enhancing the Contributions of Forests to Social and Economic Resilience. In Forests as Pillars of Social and Economic Resilience; IUFRO World Series; International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO): Vienna, Austria, 2025; Volume 45, Available online: https://www.iufro.org/media/fileadmin/publications/world-series/ws45-low-res.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2026).

- McDermott, C.; Burns, S.L.; Brockhaus, M.; Bong, I.W.; Hafferty, C.; Hirons, M.; Kumeh, E.M.; Koh, N.S.; Moeliono, M.; Pietarinen, N.; et al. A Political Ecology and Economy of Key Trends in International Forest Governance. In International Forest Governance: A Critical Review of Trends, Drawbacks, and New Approaches. A Global Assessment Report; IUFRO: Vienna, Austria, 2024; pp. 19–56. Available online: https://www.cifor-icraf.org/knowledge/publication/9202/ (accessed on 30 January 2026).

- Garrett, R.; Meyfroidt, P.; De Bremond, A.; Wartenberg, A.; Barbieri, L.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Acheampong, E.; Addoah, T.; Adeleye, M.; Alexander, P.; et al. Policy Principles for Sustainable and Just Land Systems. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2025, 12, 250810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Auwelant, E. Towards Actionable Life Cycle Assessment of Wood Systems for the Circular Bioeconomy: Biogenic Carbon Accounting, Afforestation, and Tropical Hardwood Alternatives. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium, 2025. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10067/2187110151162165141 (accessed on 30 January 2026).

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Houghton, R.A.; Fang, J.; Kauppi, P.E.; Keith, H.; Kurz, W.A.; Ito, A.; Lewis, S.L.; et al. The Enduring World Forest Carbon Sink. Nature 2024, 631, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Dhadse, S. Carbon Sequestration by Terrestrial and Marine Biodiversity—A Tool for Combating Climate Change. Sustain. Biodivers. Conserv. 2025, 4, 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Raihan, A. Enhancing Carbon Sequestration through Tropical Forest Management: A Review. J. For. Nat. Resour. 2024, 3, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal, L. Agroforestry with Hevea brasiliensis: A Landscape-Based Strategy for Carbon Sequestration and Biodiversity in Post-Conflict Colombia. Preprint 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, N.S.; Noor’An, R.F. Carbon Sequestration Potential of Rubber Plantation in East Kalimantan. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1109, 012102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgeson, J.F.; Al Kajbaf, A.; Fung, J.F. Co-Benefits of Resilience Planning: A Review of Analysis Tools and Methods. Front. Clim. 2025, 7, 1539858. [Google Scholar]