Abstract

This study presents a machine learning framework to automate the mapping of the Integrated Relative Anthropization Index (INRA, by its Spanish acronym). A predictive model was developed to estimate the degree of anthropization in the basin of Lake Tota, Colombia, using the XGBoost machine learning algorithm and remote sensing data. This research, part of a broader wetland monitoring project, aimed to identify the optimal spatial scale for analysis and the most influential predictor variables. Methodologically, models were tested at resolutions from 20 m to 500 m. The results indicate that a 50 m spatial scale provides the optimal balance between predictive accuracy and computational efficiency, achieving robust performance in identifying highly anthropized areas (sensitivity: 0.83, balanced accuracy: 0.91). SHAP analysis identified proximity to infrastructure and specific Sentinel-2 spectral bands as the most influential predictors in the INRA emulation model. The main result is a robust, replicable model that produces a detailed anthropization map, serving as a practical tool for monitoring human impact and supporting sustainable management strategies in threatened high-Andean ecosystems. Rather than a simple classification exercise, this approach serves to deconstruct the INRA methodology, using SHAP analysis to reveal the latent non-linear relationships between spectral variables and human impact, providing a transferable and explainable monitoring tool.

1. Introduction

High Andean wetlands are critical ecosystems for water regulation and biodiversity, yet they face increasing anthropogenic pressure that challenges their conservation. Lake Tota, Colombia’s largest freshwater body, exemplifies this challenge. It stores 13.55% of the nation’s water resources and supplies water to 20% of the population in the Boyacá department [1]. Despite its importance, intensive land use, primarily for agriculture, has led to severe degradation, resulting in its inclusion on the list of threatened wetlands in 2012. Located at 3015 m.a.s.l., the lake is particularly vulnerable to pollution due to low thermal variability and high solar radiation, conditions typical of high-altitude lentic ecosystems [2,3].

Traditional assessments of anthropization have often relied on land cover interpretation, a method that fails to effectively capture the spatiotemporal dynamics of landscape transformation [4]. To overcome this limitation, remote sensing and machine learning have emerged as powerful tools for more dynamic and precise monitoring [5,6].

This study proposes an innovative methodology to categorically predict the level of anthropization in the Lake Tota basin using the XGBoost algorithm. This model, known for its high accuracy in classification problems, employs boosting techniques to optimize its results [7,8]. Unlike conventional approaches, our model does not rely on static land-use categories but instead predicts the Integrated Relative Anthropization Index (INRA, by its Spanish acronym), an established methodology for quantifying human impact [9]. The model is trained on a robust set of variables, including data from Sentinel-2 imagery (spectral bands, vegetation, and moisture indices), geomorphometric information from a Digital Elevation Model (DEM), and proximity data to roads and populated centers.

Recent studies have quantified the accelerating transformation of the Lake Tota basin. For instance, between 2000 and 2020, the expansion of intensive onion cultivation (Allium fistulosum) has encroached upon the páramo ecosystem, leading to a significant reduction in native vegetation cover and increasing soil erosion rates [2]. This rapid agricultural frontier expansion underscores the urgent need for automated monitoring tools capable of tracking fragmentation patterns at a basin scale.

The primary objective is to develop a predictive model that generates a map of anthropization levels, offering a practical and replicable tool for continuous monitoring. While the use of machine learning algorithms for land cover classification is widespread, their application to emulate complex expert-based metrics remains an emerging field [10]. Furthermore, addressing the scale dependence of these indicators—a critical issue in landscape ecology known as the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP) [11]—represents a significant methodological advance. This study fills a key methodological gap by not only predicting the INRA index but also by empirically identifying the optimal spatial scale that balances predictive accuracy and computational efficiency. Therefore, the final output is not just a map, but a robust methodology designed to support decision-making in territorial and environmental management, contributing to the formulation of conservation strategies for the lake, the surrounding páramo ecosystem, and the water supply for local communities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study was conducted in the Lake Tota basin, located in the department of Boyacá, Colombia. The area is characterized by a high-altitude cold climate, with a mean temperature of 10.8 °C and annual precipitation ranging from 625 mm to 1375 mm [12]. The basin encompasses both the lake—Colombia’s largest lentic system—and a significant portion of the Tota-Bijagual-Mamapacha páramo complex, a vital ecosystem for water regulation.

2.2. Data Acquisition and Variable Preparation

2.2.1. Target Variable: Integrated Relative Anthropization Index (INRA)

The target variable for the model was the Integrated Relative Anthropization Index (INRA), which quantifies the degree of human intervention on a landscape [9]. To generate the INRA raster for the study area, we first performed a land cover classification using a Sentinel-2B Level-2A satellite image (Product ID: S2B_MSIL2A_20211201T151659_N0301_R125_T18NYM_20211201T174909.SAFE), acquired on 1 December 2021, from the Copernicus platform.

Following the methodologies of Martínez Dueñas [9] and Plaza-Ortega et al. [13], each land cover class was assigned an anthropization value on a scale from natural (0) to highly anthropic (1), as detailed in Table 1. The resulting categorized raster served as the expert-based INRA data for model training and validation. The ‘Natural lagoons, lakes, and marshes’ class was excluded from the analysis because the INRA index is specifically designed to quantify terrestrial landscape transformation and fragmentation. The spectral reflectance of deep-water bodies does not linearly correlate with the anthropization gradients defined in the INRA methodology, potentially introducing bias if treated as a standard land cover class.

Table 1.

Categorization of coverage in the study area.

2.2.2. Predictor Variables

A comprehensive set of predictor variables was compiled to train the model. These included

- Spectral Data: Original spectral bands from the Sentinel-2 image.

- Spectral Indices: Vegetation indices (NDVI, SAVI), a water index (NDWI, MNDWI), a built-up index (NDBI), and a texture index (NDTI) were calculated to characterize vegetation health, moisture, and soil conditions [14,15].

- Topographic and Edaphic Variables: A Digital Elevation Model (DEM) provided altitude data, from which the Topographic Wetness Index (TWI) was derived to estimate soil moisture patterns [16,17].

- Proximity Variables: Euclidean distances to road infrastructure and populated centers were calculated to model the influence of accessibility on anthropization.

2.3. Data Pre-Processing and Scale Optimization

All raster layers were aligned to a common spatial grid and resolution to ensure interoperability [18]. We employed bilinear interpolation for resampling continuous predictor variables (e.g., spectral bands, DEM) to preserve gradient smoothness. Crucially, for the categorical target variable (INRA classes) during the scale optimization process, we utilized a majority vote (mode) resampling approach to maintain discrete class labels and avoid the creation of artificial intermediate values. To identify the optimal spatial resolution for predicting the INRA, a scale optimization analysis was performed. We used spatial aggregation to generate datasets with pixel sizes ranging from 20 to 500 m. This process allowed us to determine the scale that best balanced model accuracy and computational efficiency while minimizing noise [19,20].

2.4. XGBoost Model Development and Evaluation

2.4.1. Model Selection

We selected the Xtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) algorithm for its high predictive performance and computational efficiency [21]. XGBoost is a gradient boosting machine that builds sequential decision trees, where each new tree corrects the errors of the previous one [22]. Its built-in regularization helps prevent overfitting, making it robust for complex environmental modeling tasks, as demonstrated in studies on land cover classification and environmental variable prediction [7,8,23,24].

2.4.2. Model Training and Hyperparameter Tuning

The model was trained to classify the INRA into six discrete categories. To address class imbalance, the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) was applied. Crucially, this oversampling was performed strictly within the training set of each cross-validation fold, ensuring that the validation sets remained composed of original, unmodified data to prevent data leakage and bias in performance metrics [25,26].

Key hyperparameters (nrounds, max_depth, eta, gamma, etc.) were optimized through a fine-tuning process using 5-fold cross-validation to identify the configuration that maximized performance and generalization capacity [27,28]. The final hyperparameters for the optimized 50 m model were learning_rate (eta) = 0.4, Gamma = 0, min_child_weight = 1, max_depth = 8, subsample = 0.9286, colsample_bytree = 0.8, and n_estimators = 400. These values prevented overfitting while maintaining high sensitivity for the minority class.

2.4.3. Performance Evaluation

Model performance was rigorously evaluated using a Repeated Random Sub-sampling Validation scheme. We performed 5 iterations (folds), where in each iteration the dataset was randomly split into 70% for training and 30% for testing. This approach ensures that performance metrics are robust to variations in data splitting. The primary evaluation metrics were Overall Accuracy [29] and the Kappa Index, which measures the agreement between predicted and actual values beyond chance [30]. A confusion matrix was also generated for each fold to analyze class-specific performance, including sensitivity and balanced accuracy.

2.5. Model Interpretability Using SHAP

To understand the contribution of each predictor variable to the model’s output, we calculated SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) values. Derived from cooperative game theory, SHAP values provide a fair and robust measure of each variable’s importance for individual predictions [31]. We also generated SHAP dependency plots to visualize how the relationship between each predictor and the INRA prediction changes across the range of the variable’s values, enhancing the ecological interpretability of the model [24].

2.6. Post-Prediction Analysis

After deploying the optimized model to generate the final INRA prediction raster, we conducted a detailed statistical analysis to validate the results. This included

- i.

- Area Comparison: Calculating the total area for each predicted INRA class and comparing it against the original classified raster to identify potential over- or underestimation.

- ii.

- Shape Metrics: Analyzing the area-to-perimeter ratio of the predicted polygons to assess landscape fragmentation and edge effects, which can indicate model performance in transition zones [32].

- iii.

- Spatial Consistency: Comparing the final prediction map with observed land cover data to verify the spatial fit and identify potential discrepancies related to human influence or positioning.

3. Results

3.1. Optimal Scale Selection

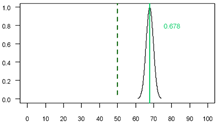

To identify the optimal spatial resolution for INRA modeling, we trained and evaluated XGBoost models at scales ranging from 20 m to 500 m. As shown in Figure 1 and Table 2, model performance was highest at finer resolutions and systematically decreased as pixel size increased. The 20 m resolution model achieved the peak metrics with a mean accuracy of 0.7689 and a Kappa index of 0.687.

Figure 1.

Average Kappa and Accuracy for each modeling resolution.

Table 2.

Model performance metrics by resolution.

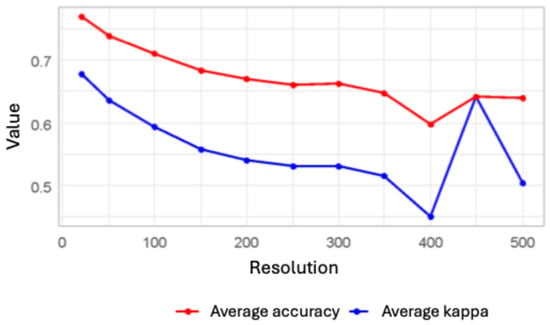

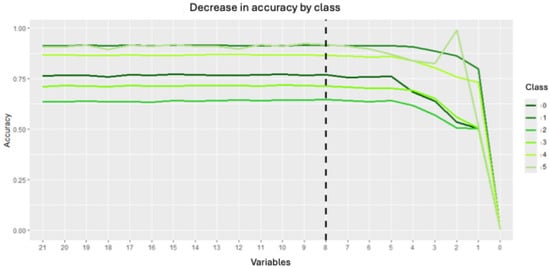

The criteria for selecting the optimal resolution prioritized a balance between computational efficiency and the ability to accurately detect the minority but high-impact ‘Total Anthropization’ class (Class 5). Despite the superior metrics of the 20 m model, the 50 m scale was selected as the optimal resolution for the final analysis. This decision was based on a trade-off between predictive accuracy and the significant computational cost of finer resolutions (the 20 m model required nearly 6 days of training) (see Table 3). Critically, the 50 m scale provided the best balance for identifying the most anthropized areas (Class 5), achieving a high sensitivity (0.8013) and balanced accuracy (0.9005) for this key category, as illustrated in Figure 2. Performance for all resolutions coarser than 200 m dropped significantly, with Kappa values approaching levels indicative of random chance.

Table 3.

Hyperparameters for the XGBoost model by scale.

Figure 2.

Balanced sensitivity and accuracy by class and resolution. The dashed vertical line represents the 50% accuracy threshold, serving as a baseline reference.

3.2. Performance of the Optimized 50 m Model

The final model at the 50 m scale was trained using the class-balanced dataset generated with the SMOTE technique. Following a 5-fold cross-validation, the optimized model demonstrated strong predictive performance. The average confusion matrix (Table 4) details the model’s class-specific performance. The model excelled at identifying the most anthropized areas (Class 5), reaching a sensitivity of 0.8278 and a balanced accuracy of 0.9137. While sensitivity for some underrepresented intermediate classes was lower, the overall performance confirms the model’s robustness for mapping human impact across the basin.

Table 4.

Metrics by category.

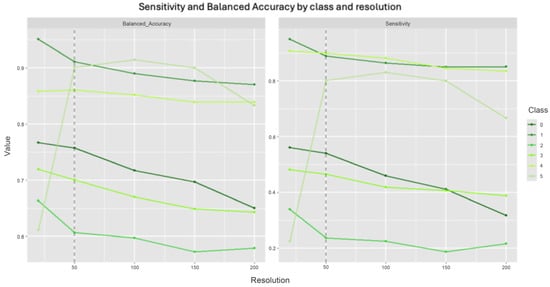

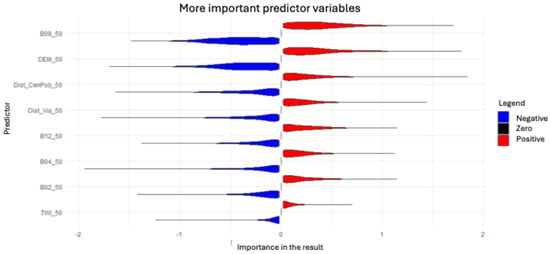

3.3. Predictor Importance and Feature Selection

A feature importance analysis based on the GAIN metric was conducted on the optimized 50 m model. The results revealed that a reduced set of 8 out of the initial 21 predictor variables contained most of the relevant information for predicting the INRA. A recursive feature elimination process confirmed this finding; removing variables beyond the top eight caused a significant drop in model performance, particularly in class-specific sensitivity (Figure 3). This allowed for the development of a more parsimonious and computationally efficient final model without sacrificing accuracy.

Figure 3.

Decreasing sensitivity by class with progressive elimination of variables. The dashed vertical line represents the 50% accuracy threshold, serving as a baseline reference.

3.4. Model Interpretability with SHAP Values

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values were calculated for the 8 selected variables to interpret the model’s predictions. The SHAP summary plot (Figure 4) highlights the relative importance of each predictor. Proximity to populated centers and roads, along with specific spectral and topographic variables, were identified as the primary drivers of anthropization.

Figure 4.

Shapley values for the most important predictors of the model.

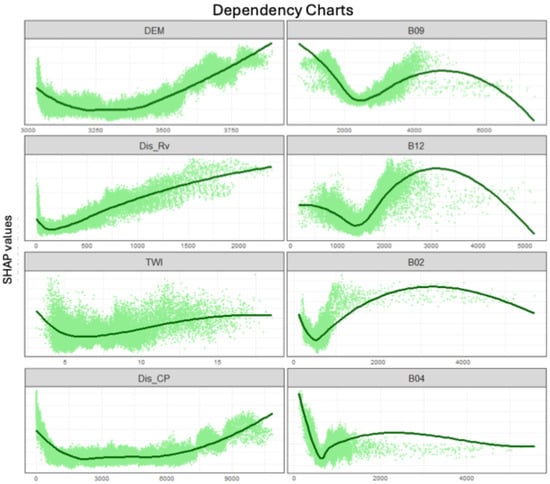

Furthermore, SHAP dependency plots (Figure 5) revealed complex, non-linear relationships between the predictors and the INRA output. For example, variables such as TWI and spectral bands (B09, B12, B04, B02) exhibited intricate patterns, while distance to infrastructure showed a more direct correlation with high anthropization scores, providing valuable insights into the landscape transformation processes.

Figure 5.

Dependency plots between each predictor and the predicted INRA.

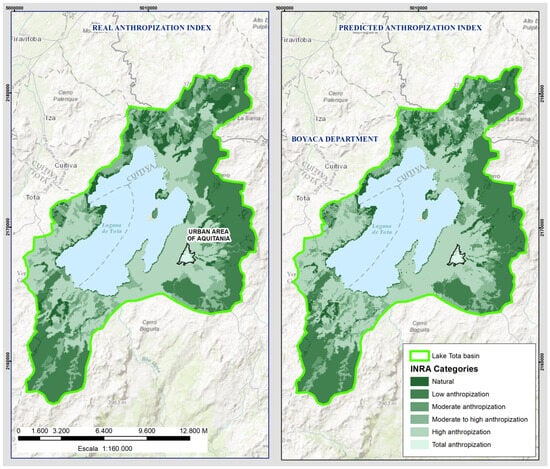

3.5. Predicted vs. Calculated INRA Map

The final optimized 8-variable model was deployed to generate a predictive INRA map for the entire Lake Tota basin at a 50 m resolution. A visual comparison between the model’s prediction and the original INRA raster (calculated from land cover classification) shows high spatial agreement in the patterns of anthropization (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Spatial comparison between the Calculated INRA and the Predicted INRA map at 50 m resolution.

This visual correspondence was confirmed quantitatively by comparing the total area of each INRA class. As shown in Table 5, the proportions of predicted anthropization levels were highly consistent with the calculated INRA data, validating the model’s ability to accurately replicate the real-world distribution of human impact on the landscape.

Table 5.

Relationship of INRA categories between the predicted and the calculated.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Anthropization Patterns in Lake Tota

It is imperative to clarify that the validation metrics presented here assess the model’s ability to emulate the expert-based INRA classification rules (internal consistency) rather than strictly validating the phenomenon against independent in situ ground control points. In this context, the machine learning model acts as a robust transfer function that automates the complex heuristic rules of the INRA methodology, dealing with the challenge of learning from derived labels [33]. By reproducing the calculated INRA with high fidelity, the model demonstrates its utility not as a generator of new ground truth, but as an efficient, automated proxy for continuous monitoring.

Our classification of the Lake Tota basin using the Integrated Relative Anthropization Index (INRA) aligns with previous studies while also revealing subtle shifts in land use dynamics. Consistent with Rojas Paéz [34], we found anthropization concentrated in agricultural areas and peri-urban zones. Our results also support findings by Arias Sosa et al. [35] of partial forest cover recovery, which our model quantified as a 7.5% increase in forested areas. However, these gains are juxtaposed with persistent ecosystem fragmentation, a concern previously raised by Salamanca [36], which may compromise ecological connectivity.

The quantitative comparison between our predicted INRA and the calculated INRA raster revealed minor discrepancies. The model tended to underestimate moderately altered areas like pastures by 7.93% and overestimate highly altered urban areas by 4.68%. These differences likely stem from the model’s difficulty in precisely delineating transition zones between land cover types, highlighting an area for future calibration.

4.2. Methodological Insights: Scale Optimization and Predictor Importance

The selection of an appropriate spatial scale is critical for landscape analysis, yet a consensus is often lacking in the literature (e.g., Pratt & Chang, 2012 [37]; Arenas-Castro et al., 2018 [38]). Our multi-scale experiment provides empirical evidence for the Lake Tota basin, demonstrating that the 50 m resolution offered the optimal balance between detail and performance. Coarser scales (>200 m) generalized the landscape to the point of omitting the most anthropized class entirely, while the finest scale (20 m) struggled to accurately classify it. Beyond computational efficiency, the 50 m resolution aligns well with the characteristic scale of land tenure in the region. Agricultural activity in the Lake Tota basin is dominated by smallholder plots (‘minifundios’ as is known in Colombia), typically ranging from 0.5 to 3 hectares. The 50 m pixel size (0.25 ha) effectively aggregates these units, reducing the high-frequency spectral noise found at 10 m or 20 m resolutions while preserving the boundaries of significant land-use changes.

This observation aligns with the well-known Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP), where statistical results are sensitive to the scale of aggregation [11,39]. In remote sensing, finding the optimal scale often involves minimizing the variance within the semantic objects of interest (in this case, agricultural plots) while maximizing the variance between them. Our findings suggest that the 50 m resolution effectively mitigates the MAUP effects for this specific fragmented landscape, avoiding the excessive noise of pixel-based analysis at finer scales while preserving the structural details lost at coarser aggregations.

At this optimal scale, SHAP analysis provided deep model interpretability, moving beyond a “black box” approach [40]. As demonstrated in recent environmental applications of Explainable AI (XAI) [41], SHAP values allow for the decoupling of correlated predictor contributions. In our study, the N-shaped dependency plots for Sentinel-2 spectral bands (B2, B4, B9, B12) reflect the nuanced spectral signatures of mixed land covers, influenced by vegetation phenology and soil moisture [42]. In contrast, variables like altitude and proximity to roads and settlements showed more intuitive trends, confirming that anthropization intensifies at lower elevations and near human infrastructure.

4.3. Model Limitations and Future Directions

A primary limitation of our model is the presence of “salt and pepper” noise in the final prediction map, a common issue in pixel-based machine learning classification [43]. This noise is ecologically meaningful, occurring primarily in ecotones between pastures and secondary vegetation. In these transition zones, pixels often contain a mixture of cover types (‘mixels’). Future improvements could implement Object-Based Image Analysis (OBIA) to classify these heterogeneous patches as single semantic units rather than relying solely on pixel-based spectral signatures [44].

Our analysis suggests this noise is not random but concentrated in two specific contexts: (1) transition zones between spectrally similar classes (e.g., grasslands and pastures), and (2) areas where functionally different land covers share similar physical properties, such as the high soil moisture found in both natural páramos and irrigated croplands. Additionally, this study utilized a single-date Sentinel-2 image, which limits the model’s ability to account for seasonal phenological variations. While sufficient for this methodological proof of concept, future iterations should incorporate multitemporal composites to improve robustness against seasonal noise and cloud cover.

Future work could mitigate this noise by implementing post-processing techniques, such as a multiple classification system (MCS) or non-local spatial filters [45]. Furthermore, the model’s diagnostic power could be enhanced by incorporating multitemporal data to analyze anthropization trends over time. Exploring advanced deep learning architectures, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), could also improve classification accuracy, particularly in complex transition zones. Finally, integrating socioeconomic data would allow for a more holistic understanding of the drivers behind landscape change.

Beyond its specific application in the Lake Tota basin, the methodology developed in this study holds significant implications for monitoring other complex environmental processes. The integrated approach, which combines spatial scale optimization, a robust algorithm like XGBoost, and interpretability analysis using SHAP, offers a replicable framework for quantifying landscape degradation across diverse ecosystems. For instance, this same approach could be adapted to assess forest fragmentation, monitor soil degradation in agricultural areas, or model unplanned urban sprawl. The model’s ability to identify the key drivers of change makes it a powerful diagnostic tool, not only for mapping environmental impact but also for informing more effective and proactive land management policies in other geographical contexts.

We acknowledge that the use of random k-fold cross-validation may yield optimistic performance estimates due to the spatial autocorrelation inherent in raster data, a phenomenon known as ‘spatial leakage’ where training and testing samples are geographically close [10,46]. While standard random CV provides a baseline for the model’s internal learning capability, recent literature suggests that spatial cross-validation (e.g., blocking or buffering) provides a more conservative and realistic assessment of generalization to unseen areas [10]. Future iterations of this work will incorporate spatial blocking strategies to strictly assess transferability.

4.4. Methodological Insights

Although the target variable (INRA) was derived from a Sentinel-2 based land cover classification, employing these spectral bands as predictors in the XGBoost model serves a distinct and valuable purpose beyond simple reproduction. Unlike traditional expert-based classification which relies on static rules, the machine learning approach establishes a dynamic and transferable transfer function. This validates the methodology on two fronts: first, it operationalizes monitoring, effectively automating the INRA calculation for future temporal analyses without the need for repetitive manual expert re-classification. Second, and perhaps most importantly, it adds a layer of ecological explainability via SHAP analysis. While the original INRA raster depicts the spatial distribution of anthropization, the predictive model deconstructs the underlying spectral and geomorphometric drivers (e.g., the specific influence of soil moisture in band B12), exposing non-linear latent relationships that standard classification methodologies fail to quantify.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we successfully developed and applied an XGBoost machine learning model to predict the Integrated Relative Anthropization Index (INRA) in the vulnerable Lake Tota basin. We demonstrated empirically that a spatial resolution of 50 m provides the optimal balance between capturing critical landscape details and model performance. The model, interpreted using SHAP values, identified key spectral features and proximity to human infrastructure as the variables with the highest contribution to the model’s decision-making process.

Despite limitations such as pixel-level noise in transition zones, the resulting anthropization map is a valuable and practical tool for environmental decision-making. It enables the identification of priority areas for conservation and provides key inputs for sustainable territorial planning. This research presents a robust and replicable methodology that significantly advances the capacity for monitoring and managing threatened high-Andean ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.C.-P., I.A.M.-G., G.Y.F.-Y. and I.F.B.-M.; methodology, A.M.C.-P., I.A.M.-G., G.Y.F.-Y. and I.F.B.-M.; software, A.M.C.-P., I.A.M.-G., G.Y.F.-Y. and I.F.B.-M.; validation, Y.A.G.-G.; formal analysis, A.M.C.-P., I.A.M.-G., G.Y.F.-Y. and I.F.B.-M.; investigation, A.M.C.-P., I.A.M.-G., G.Y.F.-Y. and I.F.B.-M.; resources, A.M.C.-P., I.A.M.-G., G.Y.F.-Y. and I.F.B.-M.; data curation, Y.A.G.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.C.-P., I.A.M.-G., G.Y.F.-Y. and I.F.B.-M.; writing—review and editing, Y.A.G.-G.; visualization, Y.A.G.-G.; supervision, G.Y.F.-Y., I.F.B.-M. and Y.A.G.-G.; project administration, G.Y.F.-Y.; funding acquisition, G.Y.F.-Y., I.F.B.-M. and Y.A.G.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad Católica de Manizales, Acuerdo No. 112: “Monitoreo participativo en territorios de agua, cuenca del río Chinchiná. Fase III”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IDEAM. Estudio Nacional Del Agua 2014; Franco Torres, O., García Herrán, M., Vargas Martínez, O., Bernal Quiroga, F., Campillo, A.K., Eds.; IDEAM: Bogota, Colombia, 2014.

- Plazas Figueroa, D.A.; Ortiz Villota, M.T. Diseño de Medidas de Manejo Ambiental Orientadas a la Disminución de Los Niveles de Eutrofización: Estudio de Caso en la MI-Crocuenca Del Río Hatolaguna en El Humedal Lago de Tota (Municipios de Aquitania-Sogamoso, Boyacá). Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Libre, Bogotá, Colombia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Northcote, T.G. Eutrofización y Problemas de Polución. In El Lago Titicaca: Síntesis Del Conocimiento Limnológico Actual; Hisbol-ORSTOM: La Paz, Bolivia, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Franco Vidal, L.; Delgado, J.; Andrade, G.I. Vulnerability Factors to Global Climate Change in the High Andean Colombian Wetlands. Cuad. Geogr. Rev. Colomb. Geogr. 2013, 22, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamanca Gómez, M.A. Multi-Timer Analysis on the Loss of the Water Mirror on Laguna La Herrera Wetland for Anthropic Effects Associated with Mining. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Militar Nueva Granada, Bogotá, Colombia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski, J.; Meinikmann, K.; Krause, S. Groundwater–Surface Water Interactions: Recent Advances and Interdisciplinary Challenges. Water 2020, 12, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.Y.M.; Masrur, A.; Adnan, M.S.G.; Baky, M.A.A.; Hassan, Q.K.; Dewan, A. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Land Use/Land Cover Change in the Heterogeneous Coastal Region of Bangladesh between 1990 and 2017. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemura, A.; Rwasoka, D.; Mutanga, O.; Dube, T.; Mushore, T. The Impact of Land-Use/Land Cover Changes on Water Balance of the Heterogeneous Buzi Sub-Catchment, Zimbabwe. Remote Sens. Appl. 2020, 18, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Dueñas, W.A. INRA—Relative Integrated Anthropization Index: A Conceptual-Technical Proposal and Its Application. Intropica Rev. Inst. Investig. Trop. 2010, 5, 37–46. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3794116 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Radočaj, D.; Plaščak, I.; Jurišić, M. A Comparative Assessment of Regular and Spatial Cross-Validation in Subfield Machine Learning Prediction of Maize Yield from Sentinel-2 Phenology. Eng 2025, 6, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, F.; Basile, M.; Balestrieri, R.; Posillico, M.; Di Donato, S.; Altea, T.; Matteucci, G. The Reliability of a Composite Biodiversity Indicator in Predicting Bird Species Richness at Different Spatial Scales. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 71, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanumen Mesa, A.M. Dynamics of Land Cover and Perception of Water Resources in the Lake Tota Basin. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Bogotá, Colombia, 2018. Available online: https://repository.udistrital.edu.co/items/4934289e-05c7-418a-865d-a186dff5065f (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Plaza Ortega, V.; Valencia Rojas, M.P.; Figueroa Casas, A. Relative Integrated Anthropization Index (INRA) Application in a High Mountain Ecosystem. Luna Azul 2017, 44, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza, A.; Roa Melgarejo, O.J.; Serrato, P.K.; León Rincón, H.A. Use of Spectral Indices Derived from Remote Sensors for Geomorphological Characterization in Island Areas of the Colombian Caribbean. Perspect. Geográfica 2018, 23, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelo Luna, D.A.; Mejía Manzano, J.; Montoya Bonilla, B.; Hoyos García, J. Analysis of the Vegetation Indices NDVI, GNDVI, and NDRE for the Characterization of Coffee Crops (Coffea Arabica). Ing. Desarro. 2021, 38, 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz Pellat, F.; Romero Sánchez, M.E.; Palacios Vélez, E.; Bolaños González, M.; Valdez Lazalde, J.R.; Aldrete, A. Scopes and Limitations of Spectral Vegetation Indexes: Theoretical Framework. Terra Latinoam. 2014, 32, 177–194. [Google Scholar]

- Raduła, M.W.; Szymura, T.H.; Szymura, M. Topographic Wetness Index Explains Soil Moisture Better than Bioindication with Ellenberg’s Indicator Values. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 85, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, T.; Kurttila, M.; Pukkala, T. Possibilities to Aggregate Raster Cells through Spatial Optimization in Forest Planning. Silva Fenn. 2007, 44, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmel, Y. Aggregation as a Means of Reducing Raster Data Uncertainty. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on GeoComputation, Southampton, UK, 8–10 September 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, D.R.; Cockburn, J.M.H.; Drǎguţ, L.; Lindsay, J.B. Local Scale Optimization of Geomorphometric Land Surface Parameters Using Scale-Standardized Gaussian Scale-Space. Comput. Geosci. 2022, 165, 105144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1603.02754v3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, L.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, F.; Yu, X.; Lu, X.; Xiang, Y. Comparison of Support Vector Machine and Extreme Gradient Boosting for Predicting Daily Global Solar Radiation Using Temperature and Precipitation in Humid Subtropical Climates: A Case Study in China. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 164, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado Guerra, D.Y. Integrated Modeling with Machine Learning to Assess Nutrient Pollution in Water Bodies Today and under the Effect of Climate Change. Application to the Júcar River Basin District. Master’s Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda Riaños, C.K.; Torres, C.A.; Zapata Calero, J.C.; Romero-Leiton, J.P.; Benavides, I.F. A Machine Learning Approach to Map the Potential Agroecological Complexity in an Indigenous Community of Colombia. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; He, D.; Wang, F. SMOTE-XGBoost Using Tree Parzen Estimator Optimization for Copper Flotation Method Classification. Powder Technol. 2020, 375, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Che, X.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Kong, D. A New Method of Diesel Fuel Brands Identification: SMOTE Oversampling Combined with XGBoost Ensemble Learning. Fuel 2020, 282, 118848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio Díaz, D.F. Classification of Mental Illnesses in Adults Using Machine Learning Techniques and Tree-Based Models in Colombian Mental Health. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de los Ándes, Bogotá, Colombia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Santarelli, J. Machine Learning Approaches to Address Subscriber Churn on a Streaming Platform in the Context of Digital Transformation. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hossin, M.; Sulaiman, M.N. A Review on Evaluation Metrics for Data Classification Evaluations. Int. J. Data Min. Knowl. Manag. Process 2015, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, R.L.; Prediger, D.J. Coefficient Kappa: Some Uses, Misuses, and Alternatives. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1981, 41, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozemberczki, B.; Watson, L.; Bayer, P.; Yang, H.-T.; Kiss, O.; Nilsson, S.; Sarkar, R. The Shapley Value in Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 31st International Joint Conference on Artifical Intelligence, IJCAI-ECAI 2022, Vienna, Austria, 23–29 July 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrig, L. Ecological Responses to Habitat Fragmentation Per Se. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2017, 48, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hell, M.; Brandmeier, M. Identifying Plausible Labels from Noisy Training Data for a Land Use and Land Cover Classification Application in Amazônia Legal. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas Paez, D. Análisis Multitemporal Mediante Imágenes Landsat Del Cambio de La Cobertura Vegetal y Su Impacto En La Desecación Del Es-Pejo de Agua En La Laguna de Tota Para El Periodo de 1991 al 2017. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Militar Nueva Granada, Bogotá, Colombia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arias Sosa, L.A.; Cely Reyes, O.A.; López Dulcey, J.R.; Ramos Montaño, C.; Rodríguez Africano, P.E.; Salamanca Reyes, J.R. Un Breve Recorrido por el Lago de Tota 2020. Available online: https://repositorio.uptc.edu.co/server/api/core/bitstreams/740253ad-09ca-467d-8f2b-acfd854faed9/content (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Forero Salamanca, J.C. Estudio de La Incidencia de Actividades Agropecuarias en Cuerpos Lénticos de Alta Montaña de La Cordillera Andina Colombiana. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Abierta y a Distancia, Bogotá, Colombia, 2021. Available online: https://repository.unad.edu.co/jspui/handle/10596/39046?locale=es (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Pratt, B.; Chang, H. Effects of Land Cover, Topography, and Built Structure on Seasonal Water Quality at Multiple Spatial Scales. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 209–210, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Castro, S.; Gonçalves, J.; Alves, P.; Alcaraz-Segura, D.; Honrado, J.P. Assessing the Multi-Scale Predictive Ability of Ecosystem Functional Attributes for Species Distribution Modelling. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comber, A.; Harris, P. The Importance of Scale and the MAUP for Robust Ecosystem Service Evaluations and Landscape Decisions. Land 2022, 11, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafarian, F.; Wieland, R.; Lüttschwager, D.; Nendel, C. Application of Extreme Gradient Boosting and Shapley Additive Explanations to Predict Temperature Regimes inside Forests from Standard Open-Field Meteorological Data. Environ. Model. Softw. 2022, 156, 105466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, G.O.d.A.; Difante, G.d.S.; Montagner, D.B.; Euclides, V.P.B.; Castro, M.; Rodrigues, J.G.; Pereira, M.d.G.; Ítavo, L.C.V.; Campos, J.A.; da Costa, A.B.; et al. Interpreting Machine Learning Models with SHAP Values: Application to Crude Protein Prediction in Tamani Grass Pastures. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binet, R.; Bergsma, E.; Poulain, V. Accurate Sentinel-2 Inter-Band Time Delays. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, V-1–2022, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, H.; Sharma, R.C.; Tomita, M.; Hara, K. Evaluating Multiple Classifier System for the Reduction of Salt-and-Pepper Noise in the Classification of Very-High-Resolution Satellite Images. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 40, 2542–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ge, Y.; An, R.; Chen, Y. Enhancing Land Cover Mapping through Integration of Pixel-Based and Object-Based Classifications from Remotely Sensed Imagery. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, F.; Xiao-Yang, Z.; Yi, L.; Xiang-Hai, W.; Yong-Gong, R. A Convolutional Neural Networks Denoising Approach for Salt and Pepper Noise. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.08176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziachris, P.; Nikou, M.; Aschonitis, V.; Kallioras, A.; Sachsamanoglou, K.; Fidelibus, M.D.; Tziritis, E. Spatial or Random Cross-Validation? The Effect of Resampling Methods in Predicting Groundwater Salinity with Machine Learning in Mediterranean Region. Water 2023, 15, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.