Abstract

Coastal erosion poses a significant risk to the Romanian Black Sea coast, a region characterized by the interaction of natural geomorphological processes and anthropogenic pressures. The research focuses on developing a tool to quantify the cumulative impact of hydro-geo-morphological factors and to assess the vulnerability of the coastal zone to these influences. The approach involves adapting the Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI)—previously applied in various methodologies—to the specific characteristics of this semi-enclosed basin, which included the exclusion of the tidal range variable due to the Black Sea’s negligible tidal amplitude. The selection of key variables, including coastal geology and geomorphology, shoreline change rates, coastal slope, sea level, and wave regime, was conducted with consideration for the specific characteristics of the Romanian coastal zone. By classifying these variables on a semi-quantitative scale and integrating them into a CVI, the study identifies and maps areas of high vulnerability. The analysis, based on a 1 × 1 km grid resolution, identified sectors of very high vulnerability in the northern Danube Delta unit, particularly along the coastlines of South Sulina–Câşla Vădanei, Sahalin, and Periboina-Edighiol-Vadu. These findings are validated through a comparison with long-term, multidecadal shoreline evolution data, confirming the model’s predictive accuracy. While the 1 × 1 km grid is effective for a macro-scale assessment, the study highlights the need for a finer resolution (e.g., 100 × 100 m) for detailed analysis in the southern region, due to localized geodynamic conditions and the significant influence of coastal infrastructure.

1. Introduction

The assessment of coastal vulnerability, particularly in the context of the Black Sea, relies broadly on methodologies such as the Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI). The CVI is a tool designed to quantify the susceptibility of coastal regions to various pressures, notably the impacts stemming from climate change, including sea level rise, erosion, and flooding. Initially developed by the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the CVI serves as a critical framework for analyzing geophysical, biological, and anthropogenic factors that contribute to coastal vulnerabilities across distinct geographic locales, encompassing both developed and developing nations [1,2,3,4].

In the Black Sea region, the assessment of coastal vulnerability using the CVI has increased importance due to the unique environmental dynamics and socioeconomic configurations of the area. Studies have highlighted the increasing risks associated with sea level rise and changing ecological conditions in the Black Sea, which are a result of climate change. For instance, a comprehensive analysis of coastal vulnerabilities demonstrates specific indices related to coastal elevation, geomorphological features, wave height, and tidal ranges that significantly influence the overall vulnerability score of various coastal segments in Bulgaria and adjacent areas [5,6]. Such assessments help identify high-risk zones, enabling policymakers and coastal managers to prioritize intervention efforts effectively.

Geographic Information Systems (GISs) have become instrumental in facilitating coastal vulnerability assessments, including the application of the CVI. The integration of satellite imagery and LiDAR data enhances the precision of these assessments, allowing for a more detailed spatial analysis of coastal areas [7,8]. In the context of the Black Sea, GIS-based methodologies enable the visualization of the interaction between anthropogenic development and natural coastal processes, thereby identifying areas where changes in land use and coastal development could intensify existing vulnerabilities [9].

Moreover, research on the Bulgarian Black Sea coastline highlights localized vulnerabilities restricted by both natural and human influences. For example, the construction of coastal infrastructure such as resorts and urban centers has significantly altered the coastal landscape, often intensifying susceptibility to flooding and erosion during extreme weather events. As evidenced in studies assessing localized sites such as Sunny Beach, the vulnerability of coastal inhabitants is compounded by unplanned urban development that fails to account for future climate scenarios [6,10]. As such, the CVI illustrates how the cumulative effects of various geological, hydrological, and socioeconomic variables converge to affect vulnerability on a regional scale.

Utilizing a series of geological and physical parameters, such as shoreline change rates and coastal slope, the CVI facilitates mapping of vulnerability across the Black Sea coast [1,3,11]. This quantitative approach allows for the classification of coastal areas into varying levels of risk, including high, moderate, and low vulnerability. Consequently, such levels update not only risk mitigation strategies but also development planning along the coastline, aiming to strengthen resilience against climate-induced hazards [12,13].

Furthermore, the application of the CVI in the Black Sea region highlights the essential need for localized research tailored to the unique environmental conditions and socioeconomic realities of coastal communities [14]. Factors such as changes in sediment flow due to river flow, alterations in sea thermal patterns due to upwelling, and agricultural runoff contribute to the vulnerability of the Black Sea coast [15]. A comprehensive understanding of these interacting components is essential for making effective coastal zone management strategies and ensuring sustainable coastal development in the face of climate change impacts [16].

The Romanian Black Sea coastline extends for 244 km, presenting a divided geomorphological and ecological profile. The northern sector is dominated by the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve, Europe’s largest nature reserve and a key source of terrigenous sand. The southern half of the coast, by contrast, is a heavily developed chain of tourist resorts, towns, and harbors built on a foundation of active cliffs and small sand bars.

The beaches in the north are primarily composed of sand borne by the Danube, whereas the sediment in the south consists mainly of biogenic shell fragments. This fundamental difference in sediment composition and origin is a key determinant of the differing erosional processes and vulnerabilities along the coast. The southern coast’s physical character is one of a predominantly erosive environment, with cliffs and beaches subject to constant change.

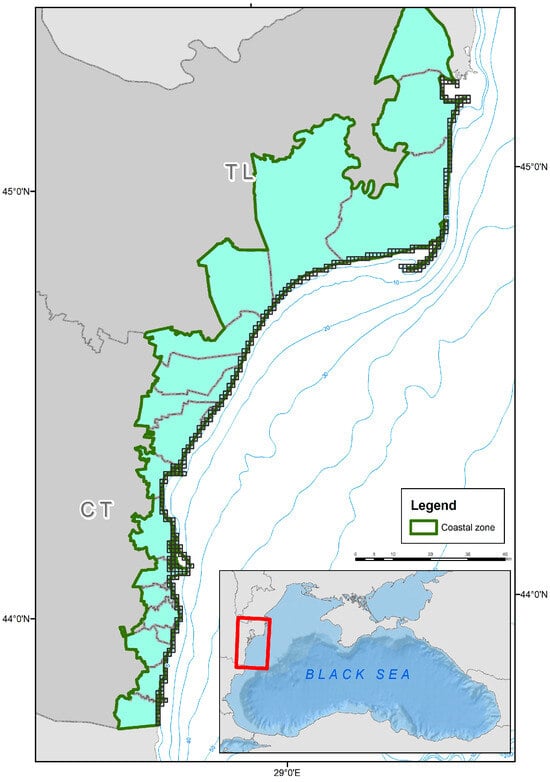

The comprehensive assessment of coastal vulnerability required a standardized spatial framework to ensure consistency and replicability. As illustrated in Figure 1, the Romanian coastline, measuring 244 km in length (extending between the Musura branch and Vama Veche) and constituting 6% of the total Black Sea coast, was partitioned into a uniform 1 km × 1 km grid. This regular grid served as the primary analytical unit for integrating and evaluating all contributing variables, enabling a systematic, macro-scale assessment of vulnerability across the entire coast.

Figure 1.

The study area is along the Romanian Black Sea coast. The two dominant administrative units delineating the study area are labeled as TL (Tulcea County) and CT (Constanța County). Bathymetric contour lines are shown at 10 m intervals, indicating the submersed coastal slope. The red box in the inset Black Sea map indicates the geographic extent of the Romanian coastal zone shown in the main figure.

The resolution of this grid, while effective for a broad-scale analysis, was a crucial methodological choice, particularly when considering the diverse geomorphological conditions of the study area. It is geomorphologically composed of both low-lying shores and high shores with cliffs. Sandy beaches account for at least 68.5% (167.3 km) of the coastal zone, of which 136 km are undeveloped beaches situated in the northern sector, primarily consisting of alluvial sediments transported by the Danube River. Anthropogenic coastal areas with infrastructure occupy 12.7% (31 km), while the remaining 18.8% of the shoreline comprises port structures.

Administratively, the Romanian coast (Figure 1) belongs to the NUTS 2 Southeast development region and the NUTS 3 counties of Constanța and Tulcea. Along the coastline, there are two municipalities (Constanța and Mangalia), four towns (Năvodari, Eforie, Techirghiol, and Sulina), and 13 communes (local administrative units), covering a total area of approximately 3575 km2. Within the coastal zone, the Constanța metropolitan area concentrates a permanent population of over 430,000 inhabitants (62% of the county’s total population), occupying only 30% of the county’s territory, with a minimum of 150,000 additional persons during the tourist season. Another area of urban agglomeration is located in the southern part of the coast, specifically the Mangalia area. The northern sector of the coastline is characterized by a low number of inhabitants and low population density values (below 50 inhabitants/km2), which is attributed to its natural conditions and its status as part of the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve.

Geographically, the study area is divided into two distinct sectors (Figure 1), a division that is critical to the study’s findings. The northern sector, labeled “TL” for Tulcea County, is dominated by the extensive fluvial-deltaic system of the Danube Delta and characterized by low-lying terrain and significant terrigenous sediment input. The southern half, labeled “CT” for Constanța County, presents a stark geomorphological contrast, consisting of a heavily developed chain of tourist resorts and towns built on a foundation of active cliffs and small sandbars. This north–south dichotomy, visually represented by the administrative boundaries, is central to understanding the differing erosional processes and varying vulnerability scores observed in the results. The presence of bathymetric contour lines further contextualizes the study area by depicting the submersed coastal slope, which, along with the emerged relief, is a key physical parameter influencing vulnerability.

The paper aims to adapt the Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI) methodology to the specific hydro-geo-morphological and anthropogenic conditions of the Romanian Black Sea coast. By adjusting the model to the microtidal setting and local dynamics, this study identifies and maps areas of very high vulnerability. The study’s primary contribution to the field is methodological originality and the establishment of a regional-scale baseline. The findings are not only an assessment; they are validated on long-term observational data, including multidecadal shoreline evolution and detailed nearshore bathymetry. This process confirms the model’s accuracy and provides a reliable tool for regional planning and site-specific decision-making. The assessment represents a significant advancement in understanding northwestern Black Sea coastal dynamics, establishing a fundamental quantitative baseline in comparison to measured natural and anthropogenic factors.

2. Materials and Methods

The data used to evaluate coastal vulnerability were integrated into corresponding variables, including geology and geomorphology, the slope of the submersed and emerged shore, sea level, shoreline changes, and mean and maximum wave height. All necessary data was stored and managed within a Geographic Information System (GIS) environment. The primary source of the data was the National Institute for Marine Research and Development “Grigore Antipa” (NIMRD) database, which contains spatial datasets representing:

- Field measurements of geomorphological parameters, such as shoreline position, beach profiles, bathymetry of the shallow water zone, and grain size analysis;

- Aerial imagery and digital terrain models (LiDAR);

- Sea level, wave, and tidal regime data from the Constanța, Sulina, and Mangalia stations.

Shoreline position data were obtained through geodetic and GIS-class and measurements conducted within the framework of the national coastal erosion monitoring program (2010–2023), which has been implemented annually across most coastal sectors. In the remote sectors of the Danube Delta, shoreline surveys have been performed using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) since 2018. The acquired aerial imagery was subsequently processed with Agisoft Metashape Professional (v1.5.1; Drone Emotions Ltd., Albiate, Italy) to produce orthophoto maps and Digital Terrain Models (DTMs). LiDAR datasets collected during the national monitoring program in 2011 and 2012 were further employed to refine shoreline position estimates and to characterize emergent topography. Long-term shoreline change (>100 years) was reconstructed using historical cartographic sources, including late 19th–early 20th century maps and mid-20th century topographic maps.

For coastal slope assessment, high-resolution single-beam echo-sounder surveys and the EMODnet Digital Terrain Model (DTM) [17] were employed to establish a multi-scale analytical framework. At the regional scale, bathymetric coverage was derived from the EMODnet DTM, with a resolution of 1/16 × 1/16 arc minutes (corresponding to an approximate grid size of ~115 m). The EMODnet DTM was used as a harmonized regional reference layer, without contributing depth values to the 0–20 m coastal zone analyzed for the CVI. All nearshore and shallow-water bathymetric data used in the vulnerability assessment were derived from NIMRD’s in situ measurements, which provide the resolution and accuracy required for coastal-scale analyses. The in situ measurements provided detailed local-scale information on seabed morphology, enabling precise characterization of nearshore gradients. Coastal slope was quantified by calculating mean gradients across three depth intervals (0–5 m, 5–10 m, and 10–20 m) along representative profiles of the Romanian Black Sea coast, ensuring consistency with regional hydrodynamic conditions.

Data processing and spatial analysis were conducted using GIS software, specifically Esri ArcGIS 10.x (California, USA), to manage and prepare the information in accordance with the CVI methodology. The study area, defined by a 1 km buffer from the coastline, was divided into a 1 × 1 km grid for analysis. The 1 km × 1 km grid resolution was adopted for CVI calculations as an optimal balance between spatial detail and data consistency, ensuring compatibility with available geomorphological and environmental datasets while capturing the pronounced morphological variability of the Romanian coast.

2.1. Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI) Methodology

The general methodological steps for calculating the Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI) are as follows:

- Step 1: Identification of Key Variables: The first step involves identifying the “key variables” that represent the significant processes influencing coastal vulnerability and evolution [18]. For this study, summarized in Table 1, the selected variables included geomorphology and geology, coastal slope, shoreline change rates, relative sea level change, and wave regime (mean and maximum wave height). A critical methodological consideration was the Black Sea’s classification as a micro-tidal environment, with a tidal range that is not a significant factor in erosional processes, so this variable was omitted from the calculation.

Table 1. The key variables used and their corresponding semi-quantitative ranking system (1–5 scale), adapted after [19,20].

Table 1. The key variables used and their corresponding semi-quantitative ranking system (1–5 scale), adapted after [19,20]. - Step 2: Quantification of Variables: Each of the key variables was quantified using a semi-quantitative scoring system on a 1–5 scale, following established methodologies from Gornitz et al. (1990) [19,20]. A score of 1 indicates a low contribution to coastal vulnerability, while a score of 5 indicates a high contribution for a specific variable in the studied area.

- Step 3: Index Calculation: The quantified variables were then integrated into a single index using a mathematical formula. The CVI was calculated as the geometric mean of the ranked variables, following a methodology adapted from [20]. The formula used is

- Step 4: Classification of Results: The calculated CVI values were classified into different vulnerability groups. This study used five classes (very high, high, moderate, low, and very low) based on two classification methods—Jenks (natural breaks) and Quantile—within the Esri ArcGIS 10x software.

2.2. Tidal and Wave Regime in the Northwestern Black Sea

Wave exposure information was derived through the interpretation of shoreline orientation and exposure patterns by the synthesis of published wave climate datasets for the Western Black Sea (WBS). These datasets provided quantitative values for significant wave height, storm frequency, and wave periods, which were compiled in Section 4, to support the vulnerability analysis.

Tidal regime information was obtained through the analysis of published tidal constituents for the northwestern Black Sea. For analyzing the tidal regime in the northwest Black Sea, the tidal regime was integrated into the Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI) framework by first identifying key variables that represent the significant processes influencing coastal vulnerability.

3. Results

3.1. Geomorphological and Geological Context

The northern unit, directly influenced by the Danube river arms and the Razim-Sinoe lagoon complex, features a lagoonal and deltaic coast with fluvio-marine and shell accumulations. These formations, rarely exceeding 2 m in height, take the form of elongated sand ridges, spits, and coastal barriers that enclose old gulfs to form marine lagoons, such as the Razim-Sinoe Lagoon Complex.

The transitional zone between Cape Midia and Cape Singhiol corresponds to the Mamaia tourist beach, which serves as a sandy barrier for Lake Siutghiol. The beach width shows significant variations along the Mamaia resort, with dimensions ranging from 30 m in the southern part to over 120 m in the northern part and is subject to erosion along its entire length (Figure 2).

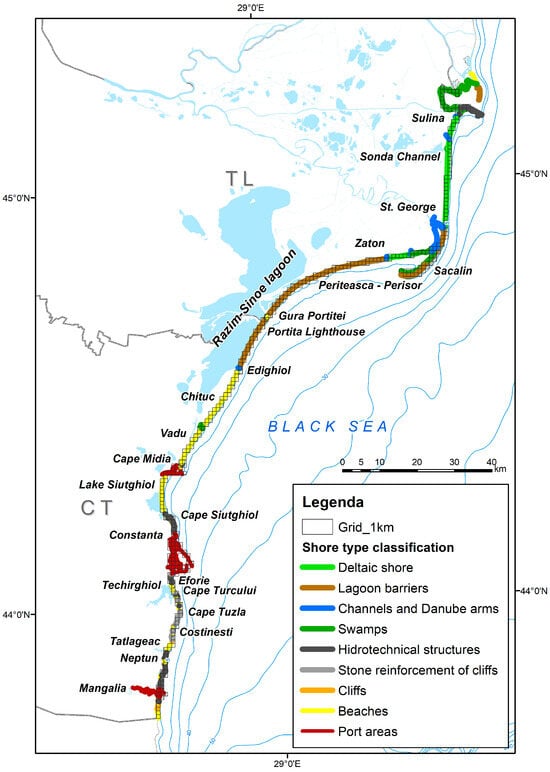

Figure 2.

The geomorphological and land use classes of the Romanian Black Sea coastline. The map illustrates the spatial distribution of the geomorphology variable (a1) used in calculating the Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI). The map visually demonstrates the dominance of deltaic, marsh, and lagoon systems in the northern Danube Delta area, as well as the prevalence of cliffs, beaches, and anthropogenic infrastructure in the southern unit.

The southern unit of the Romanian coast is governed by the presence of a Cretaceous limestone platform, well-developed cliffs, with narrow beaches formed at their base. Cliffed sectors, characterized by a succession of promontories and wide bays, alternate with accumulative shores. The presence of anthropogenic structures, including ports, tourism infrastructure, protection dikes, and hydrotechnical works, marks this entire sector. This sector has been engineered with groynes and submerged longitudinal dikes in multiple phases beginning in 1956. From north to south, the coast is marked by a succession of promontories—Cape Singol, Cape Turcului, Cape Tuzla, and Cape Aurora—which alternate with barrier-type beaches (coastal cords developed in front of limans/lagoons such as Siutghiol, Techirghiol, Costinești, Tatlageac, Neptun, and Mangalia), “pocket-beaches,” or beaches developed at the base of cliffs (Figure 2).

Sediment input to the Romanian Black Sea coast originates from three main sources: (1) fluvial deposits, primarily from the Danube River and supplemented by material transported from the Ukrainian coast; (2) terrestrial sources, derived from the reworking of deposits along the shoreline; and (3) biogenic material, consisting of shells and shell fragments, present in both the northern and southern coastal sectors. The fluvial deposits, consisting of fine, unconsolidated sediments, dominate the northern part of the littoral, while the southern littoral is characterized by loess cliffs overlying a Cretaceous limestone platform and beaches composed mainly of terrigenous sediments mixed with shell material and shell fragments.

3.2. Sea Level and Tidal Variability in the Northwestern Black Sea

Regional climatic and hydrological factors primarily influence the northwestern Black Sea’s sea level and tides, distinguishing its variability from global oceanic trends. While the region experiences a long-term sea level rise, this is subject to significant inter-annual and seasonal fluctuations driven by factors such as river runoff, atmospheric pressure, and wind patterns. Tides in the Black Sea are minimal due to its semi-enclosed nature, but localized resonance amplifies tidal constituents, particularly in the shallow northwestern shelf.

The northwestern Black Sea (NWBS) is characterized by a microtidal regime, with astronomical tides contributing only a minor fraction of sea level variability. Harmonic analyses confirm that the semidiurnal constituent M2 reaches amplitudes of approximately 2.8–3 cm, while the diurnal constituents (O1, K1) are smaller, typically ranging from 1.3 to 1.7 cm. A distinct feature of this region is the radiational solar tide S1, with amplitudes up to 4 cm, associated with diurnal atmospheric forcing via the sea–land breeze mechanism. Maximum astronomical tidal ranges rarely exceed ~18 cm in semi-enclosed estuarine systems such as the Dnipro–Bug estuary [21].

Despite the small amplitudes, local resonances play a crucial role, especially in the northwestern part of the sea. The broad, shallow shelf acts as a natural resonator, amplifying tidal constituents. This feature is responsible for the local predominance of semidiurnal tides, despite the overall tidal regime of the Black Sea being often described as diurnal [21]. The maximum tidal range for the Black Sea is estimated to be around 18 cm, which is significantly lower than in other large water bodies [21].

Even in the presence of astronomical tides, non-tidal residuals dominate sea level variability in the NWBS. Short-term oscillations are primarily driven by wind stress and atmospheric pressure. At seasonal scales, the annual mean sea level (MSL) cycle is well defined, with an amplitude of 38 ± 6 mm and a maximum in May–June. This variability reflects the freshwater budget of the basin, which is controlled by river discharge (dominated by the Danube), the precipitation–evaporation balance, and water exchange through the Bosphorus Strait [22,23]. Interannual to decadal anomalies are pronounced, often exceeding the amplitude of the seasonal cycle, with strong correlations between river inflow and coastal sea level variability [22].

The microtidal nature of the Black Sea justified excluding tidal range from the variable set; sensitivity to wave climate and relative sea level change is taken through mean/max significant wave height and sea level trend classes. This custom CVI maintained the logic of USGS-style indices while increasing local relevance. Classification using Jenks’ natural breaks and quantiles yielded similar spatial patterns, which strengthens confidence that our mapped hotspots are not objects of a particular discretization. Cross-checking CVI classes compared with shoreline variation metrics and sector-specific bathymetry provided validation at scale.

Our 1 × 1 km grid was appropriate for macro-scale and collaborative regional contrasts, but it necessarily smooths sub-kilometric processes in developed sectors. The southern unit exhibits short-wavelength variability driven by erosion, structures (such as groynes, breakwaters, and submerged rock layers), and sediment management; therefore, a nested analysis at 100 × 100 m is necessary for site-level decision support.

3.3. Wave Climate and Exposure as Key Drivers of Coastal Vulnerability

Complex interactions among wind patterns, oceanographic conditions, and climatic variability characterize the wave climate of the northwestern Black Sea. Recent studies have significantly advanced the understanding of this marine environment, focusing on aspects such as wave height, frequency, energy, and seasonal dynamics. The following sections provide a comprehensive analysis of the prevailing trends in the wave climate of the northwestern Black Sea, drawing from a variety of peer-reviewed literature.

The northwestern Black Sea exhibits significant variability in wave height and period, primarily influenced by the prevailing wind regime. Rusu et al. (2018) noted that analyzing wind and wave conditions along shipping routes offers insights into the general behavior of waves in the region, revealing a correlation with wind speed and direction, which significantly influence wave development and propagation conditions [24]. The study by Lin-Ye et al. (2018) employed a hybrid modeling approach to assess future wave storms, thereby aiding in characterizing the extreme wave climate and providing data for environmental planning in coastal areas [25].

Additionally, Nedelcu & Rusu (2021) conducted a comprehensive analysis covering six years of wind data, demonstrating the dominant wind directions and their direct influence on wave generation at the northwestern Black Sea coast [26]. This was further sustained by Çakmak et al. (2023), who employed an ensemble of dynamic wave climate models to effectively encapsulate the current wave climate and project future conditions, revealing critical insights into seasonal and interannual wave variability [27].

The analysis of wave exposure patterns along the Romanian coast highlights the significant role of wave climate in shaping the spatial variability of shoreline dynamics and the resulting Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI) classifications. The extracted exposure data indicate significant differences between protected and exposed sectors, confirming the high sensitivity of deltaic barriers and sandy beaches to dominant NE–E waves, while cliffed sectors are relatively protected.

3.4. Coastal Slope

Coastal slope is an indicator not only of the relative flood risk but also of the potential rate of shoreline retreat. A steep coastal slope implies that sea level rise would have a negligible or limited impact, whereas a low-gradient coast would experience extensive inundation even with minor sea level increases. Areas with elevations below 1 m are most susceptible to permanent flooding, while coastal sectors located within 5–10 m above the current shoreline also present a significant risk.

The morphology of the submerged shore in the northern sector varies according to the dominant coastal processes:

- In areas where sediment accumulation or dynamic equilibrium prevails (north of Sulina, north of Sfântu Gheorghe, the terminal sector of Sahalin spit, and the Perișor–Periteasca sector), the submerged shore exhibits extensive nearshore terraces flanked by multiple rows of bars, developed down to depths of 3–4 m.

- In contrast, in sectors affected by erosion, the nearshore terraces are less developed, the number of bars decreases to 1–3, and in some areas they disappear entirely, resulting in a concave profile (central Sulina–Sfântu Gheorghe sector, central Sahalin Peninsula, Zăton–Perișor, and Portița–Periboina)

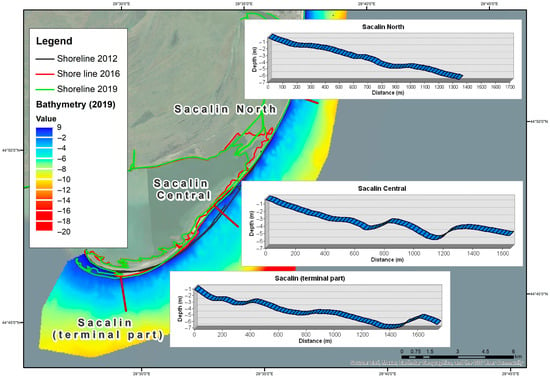

The three bathymetric profiles on Sahalin spit (Figure 3) provide a more detailed view of the submerged coastal slope. These profiles illustrate the complexity of the seabed, which is typical for a fluvio-marine environment with significant sediment input from the Danube River. The profiles reveal a varied morphology, characterized by subtle depressions and elevations on the seafloor, which reflect the dynamic processes of sediment transport and deposition in this area.

Figure 3.

Shoreline evolution and nearshore bathymetric profiles of the Saint George–Sahalin coastal sector. The main map displays bathymetry, with blue/cooler colors indicating shallower depths and warmer colors (red/orange) colors representing deeper waters. The overlaid lines represent the shoreline positions for 2011 (green), 2016 (black), and 2017 (blue), illustrating the erosional trend in this sector (data source: NIMRD database).

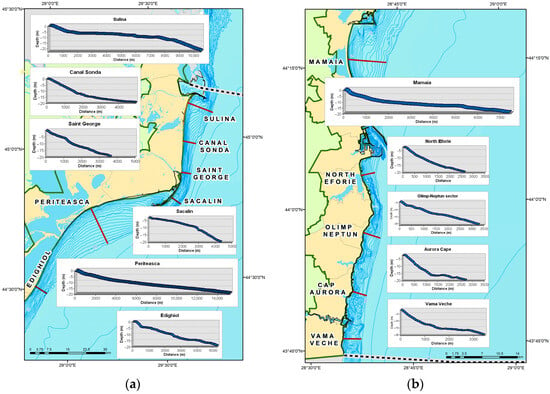

The nearshore bathymetric profiles displayed in Figure 4a,b offer a detailed, high-resolution view of the submerged coastal slope, providing essential data that support the overall Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI) assessment of the Romanian Black Sea coast. These profiles visually emphasize the geomorphological dichotomy between the northern and southern units, which is a key determinant of the differing vulnerability scores observed across the study area. The profiles in Figure 4a for Edighiol, Chituc, and Vadu, originate from the northern, fluvio-deltaic region of the Danube Delta. This area is characterized by low-lying terrain and beaches composed mainly of Danube-transported sand. These profiles reveal a subtle, low-gradient morphology of the submerged slope, characteristic of an environment receiving extensive sediment input and undergoing dynamic depositional processes. This pattern stands in contrast to the more complex nearshore profiles observed along the central and southern coast.

Figure 4.

Nearshore bathymetric profiles of the Romanian Black Sea coast: (a,b) present cross-sectional bathymetric profiles of the submerged coastal slope at key locations along the Romanian Black Sea coastline. (a) shows profiles for the northern sectors, and (b) details profiles for the southern unit (data source: [17]).

The profiles for the southern part of the coast, including those in Figure 4b (Eforie, Costiensti, Vama Veche) and for Mamaia and Constanța in Figure 4a, correspond to a heavily developed region built on active cliffs and sand bars. Sediments in this area consist primarily of biogenic shell fragments. The profiles demonstrate a distinct nearshore morphology, reflecting the complex interplay between natural erosional processes and significant anthropogenic influences. As the CVI study highlights, this coast is a predominantly erosive environment where cliffs and beaches undergo constant change. The detailed profiles provide the granular data necessary to accurately capture the specific, localized vulnerabilities of this developed coastline.

The quantitative analysis of the nearshore seabed morphology, structured in Table 2 by northern, transitional, and southern units, highlights a pronounced distinction in submerged coastal characteristics. Profiles within the northern unit (e.g., Sulina and Zaton), are characterized by relatively low average and maximum depths, and gentle average slopes, indicating a low-gradient depositional environment. In contrast, the southern unit (e.g., Eforie and Cape Tuzla) exhibits significantly greater maximum depths and steeper average slopes. For instance, the average slopes at Cape Tuzla reach 1.18% and at Eforie, 0.87%. These values contrast sharply with the typically lower slopes found in the Northern Unit, such as Sulina Beach (0.24%) or Zaton (0.14%). These values contrast sharply with the typically lower slopes found in the Northern Unit, such as Sulina Beach (0.24%) or Zaton (0.14%). This quantitative data on slope and depth serves as critical evidence that supports the study’s geomorphological findings. It confirms the description of the northern deltaic coast as low-lying and the southern coast as a more energetic, erosional environment dominated by cliffs and engineered structures. The transition unit profile at Mamaia shows intermediate characteristics, which reinforces the spatial progression from the low-energy north to the higher-energy south.

Table 2.

The morphological parameters of the submerged coast.

3.5. Dynamics of the Northern Unit (Danube Delta)

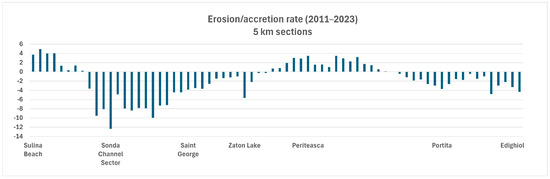

The shoreline changes rates for the northern Romanian Black Sea coast during the 2011–2020 period provide quantitative evidence of the coast’s instability. The trends represented in Figure 5 highlight the highly dynamic nature of this fluvio-deltaic coastline, where shoreline change is a key CVI variable.

Figure 5.

Shoreline change rates in the northern unit of the Romanian Black Sea coast (2011–2020). The bar chart illustrates the annual rates of shoreline change in meters per year (m/yr) for key sectors. Positive values indicate accretion (accumulation), while negative values represent erosion.

In the northern coastal unit, shoreline evolution is determined by the intensity of coastal processes, which define distinct sectors (Figure 5):

- Sectors with pronounced erosion: Canal Sonda–Casla Vădanei, Zăton–Perișor area, and the northern Portița–Periboina–Edighiol sector, with annual retreat rates calculated for 2011–2020 ranging between 5 and 10 m/yr.

- Sectors dominated by accretion, interspersed with areas of relative equilibrium: Sulina beach (5–13 m/yr), southern Perișor–southern Periteasca (2–5 m/yr), and Chituc barrier (Vadu area) (3–7 m/yr).

- Narrow littoral spits with marked dynamic behavior: arcuation and elongation toward the southwest, accompanied by westward translation (Musura Bay island and Sahalin Peninsula).

The graphic distinguishes two dominant processes: significant erosion is evident in sectors with negative values, such as Canal Sonda, Casla Vădanei, and Periboina, where rates reached up to 10 m/yr. This high recession rate directly contributes to the elevated CVI score and underscores the constant change in this erosive environment. On the other hand, robust accretion is demonstrated in different areas, with positive values exceeding 5 m/yr at locations such as Sulina Beach and Vadu.

These sectors of accumulation and relative equilibrium reflect the variability of hydrological and morphological factors, such as local shoreline orientation, sediment input, and the influence of coastal structures. These factors are the primary drivers of contrasting erosional dynamics and contribute to the high overall vulnerability of the northern coast.

3.6. Dynamics of the Southern Unit (Cliffed and Developed Coast)

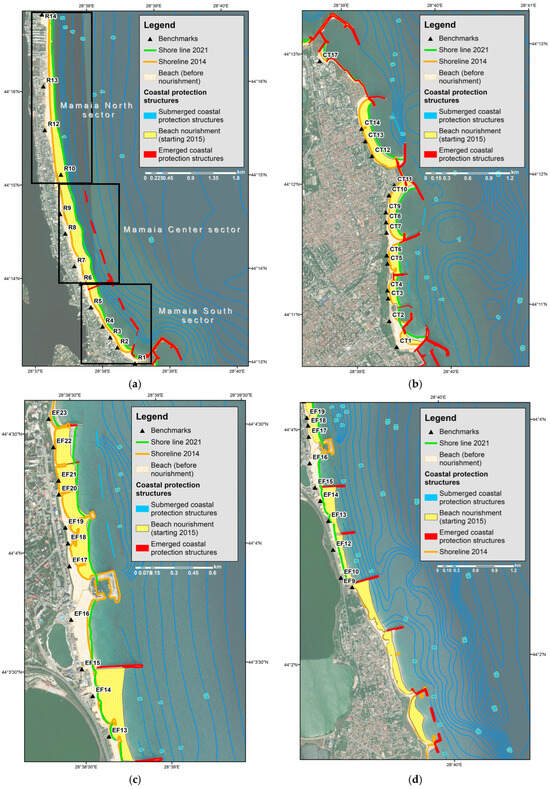

In the southern unit (Cap Midia–Vama Veche) (Figure 6), the mobility of the shoreline exhibits a different evolution compared to the northern unit, characterized by low and irregular rates, largely due to the presence of the submerged Sarmatian limestone platform and coastal protection structures.

Figure 6.

Detailed shoreline dynamics and anthropogenic structures in the developed southern coastal unit of the Romanian Black Sea from 2014 to 2021: (a) focuses on the Mamaia sector, (b) on Constanța sector: CT1 to CT17, (c) on the Eforie North sector: EF13–EF23, and (d) on the Eforie South sector: EF9 to EF19. The triangular markers labeled “Benchmarks” in (a–d) serve as a critical methodological function as Ground Control Points (GCPs), which are essential for ensuring the geometric accuracy of the multi-temporal analysis. These points correspond to stable, clearly identifiable features (such as corners of seawalls, fixed road structures, or prominent building edges) that are assumed to have remained unmoved between the image acquisition dates (Shoreline 2014 and Shoreline 2021). Their function is to create high-precision geometric correction and ensure the rectification of the aerial and satellite imagery used. This process minimizes measurement error when assessing the shoreline shift (pre-nourishment vs. post-nourishment) and accurately mapping the extensive anthropogenically driven geomorphic shift that resulted from the 2015 beach nourishment projects.

Figure 6a–d presents a high-resolution, multi-temporal analysis of shoreline position, nearshore bathymetry, and coastal protection infrastructure for the heavily anthropized southern unit of the Romanian Black Sea coast, covering the Mamaia-Constanța, Eforie Nord, and Eforie Sud sectors. The main maps, with their overlaid shoreline positions from 2014 to 2021, illustrate the highly dynamic nature in four important locations, highly anthropized sub-sectors: Mamaia (a), Constanța (b), Eforie Nord (c), Eforie Sud (d).

Since the 19th century, coastal protection systems—ranging from “soft” to “hard” engineering solutions—have been implemented in stages across southern part of Romanian littoral to mitigate erosion, including longitudinal and transverse breakwaters, submerged breakwaters, groynes, and artificial beach nourishment, with major rehabilitation projects between 2013 and 2015 and continued efforts under the 2014–present. These interventions have significantly altered sediment transport along the shoreline and reshaped both hydrodynamic processes and the morphology of emerged and submerged beaches.

Although the evolution of this area has remained within narrower limits of modification rates (erosion) compared to the northern sector, certain sections have experienced significant negative effects, with the beach sometimes disappearing entirely (e.g., Eforie Nord Beach before nourishment works, Cap Aurora, etc.).

The comparative assessment of the shoreline 2014 (pre-nourishment) and shoreline 2021 (post-nourishment) positions demonstrates a considerable, anthropogenically driven geomorphic shift. The yellow shaded areas, representing the track of the large-scale beach nourishment projects (2015), explain the resulting massive beach progradation and widening. This intervention has altered the natural shoreline position, effectively overriding the historical erosional trend to create a stabilized, artificial barrier. The stability is further maintained by a network of submerged (blue) and emerged (red) coastal protection structures, which function to dissipate wave energy and anchor the artificial beach fill, a necessary response to the predominantly erosive environment of the southern coast. However, the complex, localized nature of these structural interventions—including groynes and submerged dikes—creates highly variable stability patterns, confirming that a finer spatial resolution is required to accurately assess site-specific vulnerabilities and the long-term effectiveness of individual defense structures.

Table 3.

Wave exposure and wave climate parameters for the Romanian (Western) Black Sea coast.

Table 3.

Wave exposure and wave climate parameters for the Romanian (Western) Black Sea coast.

| Sector | Exposure Condition | Wave Climate Parameters (Hs, Tp, Storm Data) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sulina—near breakwaters | Wave front protected by Sulina training walls | Mean Hs ~0.8–1.0 m | [28,29] |

| max storm Hs ~5–6 m | |||

| dominant NE–E waves | |||

| Tp ~5–6 s | |||

| Offshore barrier/island (Sahalin, Musura) | Exposed to offshore waves from NE and SE | Mean Hs ~0.9–1.2 m | [10,29] |

| storm Hs up to 6–7 m | |||

| peak Tp 7–9 s | |||

| Central deltaic coast (Casla, Periboina–Edighiol) | Protected from northern waves | Mean Hs ~0.7–1.0 m | [30,31] |

| storm Hs ~4–5 m | |||

| NE dominance is reduced by local protection. | |||

| Transitional sector (Mamaia–Midia) | Exposed to NE and SSE waves; protected from southern waves | Mean Hs ~0.8–1.0 m; | [23,32] |

| max ~5–6 m | |||

| dominant NE and SSE directions | |||

| Southern coast (Constanța–Eforie–Mangalia) | Mostly protected from southern waves, with local exposure varying depending on orientation and groynes. | Mean Hs ~0.7–0.9 m | [29,33] |

| storm Hs ~5–6 m | |||

| Tp 4–6 s (reasonable meteorological conditions) | |||

| 7–8 s (storms) | |||

| General wave regime (Western Black Sea) | Significant wave height (Hm0) increases for NE and E; protected from southern waves. | Mean Hs 0.5 to 2.5 m | [10,26,27,29,34,35] |

| Significant Wave Height reflects the highest one-third of waves, averages around 1.5 m, and has a maximum of 6–7 m (based on in situ observations) | |||

| dominant NE–E directions, mainly from the NW quadrant, with variances observed during storms | |||

| 20–25 storm days/year | |||

| Tp 4–9 s |

The ‘key’ variables are classified on a scale from 1 to 5 (from low risk to high risk) by dividing them into five classes (Table 3). The classification adopted in this study was adjusted to represent the characteristics of the Black Sea basin, based on the approaches of Gornitz (1991) [19], Shaw et al. (1996) [36], Thieler and Hammar-Klose (2000) [37], and Lopez et al. (2016) [38]. A value of 1 indicates a low contribution of a specific key variable to the coastal vulnerability of the studied area or subareas, whereas a value of 5 indicates a high contribution.

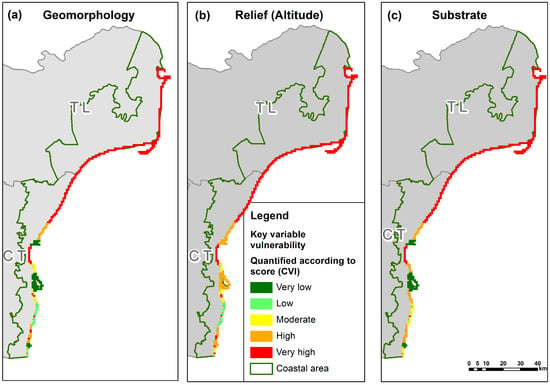

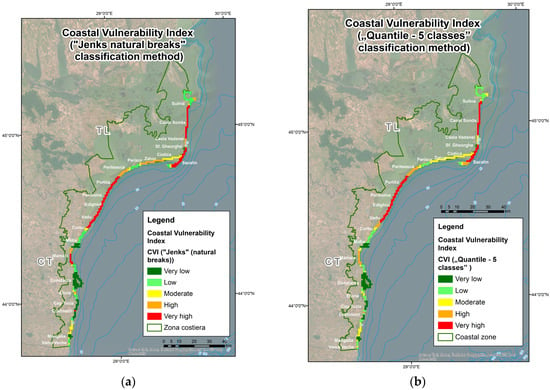

The northern unit, encompassing the Danube Delta (TL), is categorized as a zone of High to Very High vulnerability (red, orange, and yellow classes in the key variables classified as maps). This ranking directly reflects the intrinsic geomorphic sensitivity of the deltaic systems, specifically the unconsolidated fine sediments, low-lying terrain, and high exposure to wave action (Figure 7a–f).

Figure 7.

Graphical representation and classification of key CVI variables for the Romanian Black Sea coast. (a–f) present the spatial distribution of six key variables quantified and classified according to the CVI methodology that shows (a) the Geomorphology, (b) Relief (Altitude), (c) Substrate, (d) the Coastal Slope, (e) Shoreline Change Rate, and (f) Wave Exposure variables. The legend indicates the CVI ranking from “Very Low” (green) to “Very High” (red), with each color representing a specific contribution to coastal vulnerability. The map delineates the two primary administrative units: TL (Tulcea County) and CT (Constanța County), as shown in Figure 1.

The key variables quantified for the Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI) are represented in Figure 7a–d, visually establishing the pronounced north–south geomorphological and geodynamic dichotomy that supports the final vulnerability assessment of the Romanian Black Sea coast. The Geomorphology map (Figure 7a) clearly distinguishes the two coastal sectors: the northern sector (TL) predominantly classified as “Very High” vulnerability (red) reflecting the intrinsic dynamic and unstable nature of its low-lying deltaic and marsh systems and the southern sector (CT) exhibits a heterogeneous pattern, ranging from “Very Low” to “Low” vulnerability (dark and light green) where active cliffs provide stability, to localized areas of “Very High” vulnerability (red) corresponding to sandy beaches and tourist resorts.

Similarly, the spatial distribution of key vulnerability factors clearly reflects the north–south geomorphological gradient: the Relief (Altitude) map (Figure 7b) reflects the “Very High” vulnerability correlated with northern sector, where the terrain is predominantly low-lying, falling within 0–5 m altitude range above sea level that received a “Very High” vulnerability score (Table 1). On the other hand, the southern unit presents varied, generally lower vulnerability scores, corresponding to the higher altitudes of the protective cliffed sections. The Substrate map (Figure 7c) follows the relief pattern: the northern delta’s composition of fine, unconsolidated sediments results in a “Very High” vulnerability rank, while the hard–rocky substrate present at the base of the cliffs along the southern coast contributes to a lower vulnerability score.

The northern, low-energy deltaic zone is classified as “Very High” vulnerability (red) due to its very gentle slope (<2%) (Figure 7d). The southern, high-energy environment, characterized by cliffs and engineered structures, exhibits steeper slopes that result in lower vulnerability rankings.

The coast’s dynamics are represented by the Shoreline Change Rate map (Figure 7e). The northern delta is characterized by extensive areas of “High” to “Very High” vulnerability (orange and red), reflecting the significant erosional trends and rapid accretion rates known in this fluvio-deltaic region [22,28,31]. The southern unit, although a “predominantly erosive environment,” shows a more varied pattern of vulnerability due to the mitigating effect of coastal protection works that stabilize the shoreline in localized areas [30,32]. The Wave Exposure map (Figure 7f) delineates the open exposure of the northern coast to waves, contributing to its elevated vulnerability. In contrast, the southern coast pattern is more varied, influenced by localized coastal geometry and the presence of protective infrastructure that modifies wave action.

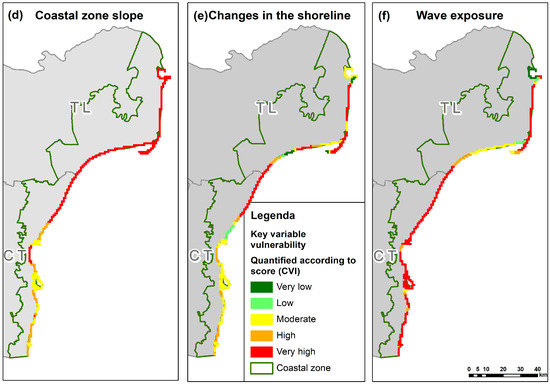

The final CVI scores, derived from the analysis and integration of the six key variables, are presented in Figure 8a,b. These maps represent the primary result of the CVI methodology, offering an evidence-based assessment of the Romanian Black Sea coast’s susceptibility to hydro-geo-morphological factors and natural hazards. The utilization of two distinct classification methods—Jenks (natural breaks) and Quantile—underscores the robustness of the findings, as both approaches yield a comparable spatial pattern of vulnerability.

Figure 8.

Results of the CVI application for the Romanian Black Sea coast. (a,b) present the processed CVI scores, classified into five vulnerability classes from “Very Low” to “Very High” as Table 1 and calculated using Equation (1). (a) uses the “Jenks (natural breaks)” classification method, while (b) uses the “Quantile” method. The maps visually summarize the cumulative impact of key physical variables—including geomorphology, relief, shoreline change rate, and wave regime—to identify areas of high vulnerability.

4. Discussion

The application of a regional Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI) provides an evidence-based framework for assessing and mapping the vulnerability of the Romanian Black Sea coast to natural and anthropogenic pressures.

This study adapted the Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI) basis to the microtidal setting of the Black Sea and to the specific hydro-geo-morphological and anthropogenic conditions of the Romanian coast. By excluding tidal range, we ranked regional variables (geomorphology and substrate, relief, coastal slope, shoreline change, relative sea level change, and wave regime). We applied a 1 × 1 km grid to produce synoptic vulnerability maps that highlight the north–south contrast and local hotspots shaped by human interventions. The mapped patterns, together with In Situ shoreline and nearshore morphology data, support our working hypotheses: (i) deltaic and lagoonal sectors with low relief and unconsolidated sediments are intrinsically more vulnerable than cliffed sectors; and (ii) in developed reaches, infrastructure and coastal works moderate vulnerability at sub-kilometric scales, often prevailing larger geomorphology patterns.

The CVI model suggests that this entire sector is a zone of very high vulnerability. The maps specifically identify sectors with very high vulnerability scores in the areas of South Sulina–Câşla Vădanei, Sahalin, and Nord Gura Portitei–Periboina–Edighiol–Vadu. This is a direct consequence of the area’s physical characteristics, which include low-lying terrain, unconsolidated fine sediments from the Danube River, and a highly dynamic environment with significant rates of both erosion and accretion. In contrast, the southern unit (CT) shows a more complex and heterogeneous pattern of vulnerability. While there are segments classified as “Very Low” to “Low” (dark and light green) corresponding to the stability of active cliffs, significant sections are categorized as “High” and “Very High” vulnerability. The areas with the highest vulnerability in the south, such as Mamaia, Eforie Nord–Eforie Sud, and Costinești, generally overlap with the sandy beaches that have formed in front of old limans. This highlights how localized geodynamic conditions, coupled with extensive anthropogenic infrastructure, create a variety of vulnerabilities on a smaller scale.

A comparison can be established between our findings for the Romanian sector and those reported for adjacent regions of the Western Black Sea, particularly the Bulgarian and Turkish coasts, where similar CVI-based approaches and shoreline change assessments have been undertaken. Studies along the Bulgarian coast [5,6] identify the low-lying sandy systems of the northern Bulgarian shoreline—such as Shabla–Tyulenovo, Varna Bay, and the highly urbanized Sunny Beach barrier—as exhibiting high to very high vulnerability. These sectors share geomorphological and hydrodynamic influences comparable to those observed in the northern Romanian unit: unconsolidated sediments, low elevations, and exposure to the dominant NE–E storm waves. Reported erosion rates on the Bulgarian coast in such settings typically range between 1 and 3 m/yr, with higher values near inlets or engineered structures. These are broadly consistent with the erosional patterns we document for the Danube Delta sectors (e.g., Casla Vădanei, Periboina), although the latter show even greater variability (up to 10 m/yr locally), driven by the delta’s sediment-rich but morphodynamically unstable barrier systems.

Similarly, the southern Romanian findings align with results from Bulgarian urbanized sectors such as Varna, Burgas, and the Sunny Beach–Nessebar region, where extensive engineering interventions have created a variety of locally stable but regionally vulnerable beaches. As in our results, CVI applications in Bulgaria highlight how protective structures, pocket-beach morphology, and cliffed promontories result in highly heterogeneous vulnerability patterns at sub-kilometric scales. This similarity reinforces the conclusion that engineering interventions significantly constrain natural sediment pathways in both countries, thereby requiring finer-scale assessment of grids to capture local variability.

Similarities may also be showed with the Turkish Black Sea coast, particularly between Istanbul and the western Anatolian sectors, where CVI and shoreline-change analyses (e.g., Musa et al., 2014 [11]; regional assessments cited in Hamid et al., 2019 [3]) highlight persistent erosion of sandy beaches and accretion near river mouths. Turkish studies similarly point to the role of microtidal wave-dominated conditions, high storm-wave energy from the north, and high sediment mobility—processes parallel to those driving the vulnerability of the Romanian northern sector. While erosion rates reported for the Turkish coast are generally moderate (0.5–2 m/yr), they remain comparable to those observed along Romania’s central and southern coastlines prior to large-scale nourishment. Moreover, Turkish assessments emphasize the influence of anthropogenic structures on sediment classification, corresponding the observed site-specific behavior of Romanian sectors such as Mamaia, Eforie, and Costinești.

These cross-border comparisons demonstrate that the spatial patterns noticed by our personalized CVI—high vulnerability in deltaic and barrier environments, lower vulnerability in cliffed sectors, and strong local effects of engineering works—are consistent with the broader regional response of Western Black Sea coasts to common hydrodynamic, geological, and anthropogenic influences.

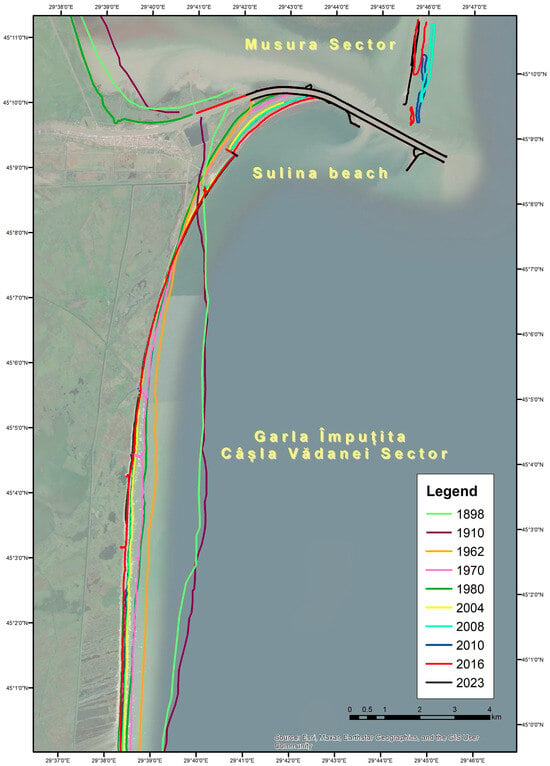

The long-term shoreline evolution at Sulina Beach (Figure 9) establishes a long-term progradational trend, pronounced in northern and central sectors. This sustained seaward advance reflects the altered coastal circulation patterns generated by the Sulina Channel jetties, which have modified sediment pathways and enhanced local sediment retention. The resulting morphological stability and gradual accretion are fully consistent with the CVI classification of this sector as exhibiting low to moderate vulnerability. The multi-decadal evidence (Figure 9) underlines the ability of engineered structures to apply a control on sediment dynamics and shoreline position, effectively stabilizing a coast that would otherwise be characterized by the inherent variability typical of deltaic environments.

Figure 9.

Long-Term Shoreline Evolution and Anthropogenic Influence near the Sulina Channel, Northern Danube Delta (1898–2023).

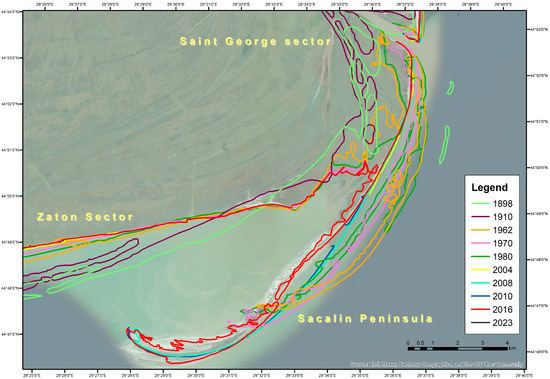

In contrast to the Sulina sector, the Sahalin–Zatoane area (Figure 10) is represented as a highly dynamic and complex evolution. Figure 10 exhibits significant changes in the shape and position of the Sahalin peninsula over more than a century. The data demonstrates a pronounced translational movement of the coastal barrier towards the west, accompanied by both erosion and accumulation. This dynamic is reflected in the CVI assessment, which classifies this sector with very high vulnerability scores. The formation and continuous reshaping of the Sahalin peninsula also serve as a protective function, shielding the inner coastal sectors from the intense action of dynamic factors, such as waves generated by storms from the north and northeast.

Figure 10.

Long-Term Shoreline Evolution and Translational Dynamics of the Sahalin–Zatoane Peninsula, Romanian Black Sea Coast (1898–2010).

4.1. Shoreline Changes Along the Northern Unit of the Romanian Coast

The geomorphological and bathymetric data presented in Figure 3 provide high-resolution evidence that verifies the macro-scale CVI assessment, which identified the Danube Delta coastline, including the Sahalin sector, as an area of very high vulnerability. The observed erosional trend directly aligns with the study’s findings that deltaic systems are assigned a very high CVI ranking due to their dynamic and vulnerable nature.

The intensity of coastal processes determines the evolution of the shoreline within the northern unit (Figure 5), which delineates distinct sectors:

- Sectors with Pronounced Erosion: These include the Canal Sonda–Casla Vădanei, the Zatoane–Perisor area, and the Nord Portita–Periboina–Edighiol sector. Annual erosion rates for the 2011–2020 period in these areas ranged from 5 to 10 m/yr.

- Sectors with Predominant Accretion: These sectors are scattered among those in a state of relative equilibrium. Distinguished areas of accumulation include Sulina Beach (with rates of 5–13 m/yr), the southern Perisor–southern Periteasca area (2–5 m/yr), and the Chituc sandbar in the Vadu area (3–7 m/yr).

- Narrow Coastal Barriers with Distinct Dynamics: These barriers, such as the Musura golf island and the Sahalin peninsula, exhibit a specific, pronounced dynamic characterized by arciform and enlargement towards the southwest, accompanied by a translational movement to the west.

The CVI highlights very high vulnerability along South Sulina–Câşla Vădanei, Sahalin, and Nord Gura Portiţei–Periboina–Edighiol–Vadu, cohering with the mixture of extremely low elevations (0–5 m), fine unconsolidated sediments, gentle coastal slopes (<2%), and energetic exposure to N–NE storm waves (Figure 7 and Figure 8). These physical settings lead to rapid morphological change along the coast, as our shoreline analysis exposes pronounced erosion (up to ~10 m·yr−1) and dynamic local accretion (≥5 m·yr−1) over the period 2011–2020 (Figure 5). Such association of retreat and progradation is characteristic of fluvio-deltaic coasts where sediment transport, longshore gradients, and episodic storms interact nonlinearly consistent with earlier multidecadal observations from the Danube Delta and adjacent barriers.

The low vulnerability ranking is substantiated by the nearshore bathymetry which reveals subtle, low-gradient submerged slopes and low average depths typical of a depositional environment. For instance, bathymetric profiles in the Sulina sector show a consistent, gentle seaward slope with low maximum depths, contrasting sharply with the steeper profiles of the South (Figure 4a).

The dynamics observed in this unit are co-determined by natural morphodynamics and coastal engineering interventions. The mapping of very high CVI classes along the Sahalin peninsula aligns with its long-term instability, which is characterized by a pronounced westward translational movement and alternating erosion-accretion cells documented over a 125-year period (Figure 10) [28,30,31]. This high mobility is a consequence of the feature’s exposure to intense wave action and the unconsolidated fluvio-deltaic sediments. While the lower CVI levels at Sulina Beach are confirmed by the long-term progradation indicator shown in Figure 9. This seaward accretion is a direct result of breakwater-induced stabilization and sediment trapping, where human engineering has locally superseded the natural deltaic dynamism (Figure 9 and Figure 10). The shoreline evolution data and the nearshore bathymetry provide compelling evidence that the physical characteristics of the Saint George–Sahalin sector make it one of the most vulnerable sections of the Romanian Black Sea coast (Figure 5).

4.2. Shoreline Changes Along the Southern Unit of the Romanian Coast

In the southern unit (Cape Midia-Vama Veche) (Figure 6), shoreline movement exhibits a different evolution compared to the northern unit, with small and non-uniform rates. This is primarily due to the presence of the submarine Sarmatian limestone platform and coastal protection works. Although the evolution of this zone has remained within a narrower range of change (erosion) rates compared to the northern sector, certain areas have experienced significant negative effects, with beaches sometimes disappearing entirely (e.g., Eforie Nord Beach before renourishment works, Cape Aurora, etc.).

The spatial data (Figure 6) confirms the key finding that coastal vulnerability in this region is defined by a complex interplay between natural erosional processes and extensive human engineering. The data presented substantiates the key finding of the CVI assessment, which highlights the significant influence of coastal infrastructure and localized geodynamic conditions on the vulnerability of this region.

In the south, CVI classes are heterogeneous: cliffed promontories on Sarmatian limestone often register low vulnerability (Figure 7a–c), while sandy pocket beaches fronting former limans (Mamaia, Eforie, Costinești) are ranked high to very high. This heterogeneity reflects the more energetic environment, characterized by steeper, more complex nearshore profiles (Figure 4b) and dense coastal infrastructure. The multi-annual shoreline positions show varieties of local accretion adjacent to defense structures and erosion in unprotected or downdrift cells (Figure 6), aligning with the bathymetric evidence of complex nearshore morphology (Figure 3 and Figure 4b, Table 2) and supports site-specific studies on the efficacy of anthropogenic interventions in areas like Eforie and Mamaia [30,32].

In the northern sector, the Sulina breakwaters produce localized shelter, altering the natural wavefront and promoting progradation in some areas (e.g., Sulina Beach). Moreover, offshore barriers such as Sahalin remain directly exposed to long-fetch northeast and southeast waves, leading to barrier translation and very high vulnerability scores. The central deltaic stretches, including Casla–Periboina–Edighiol, benefit from partial protection against northern waves and remain highly dynamic due to their exposure to northeast and southeast storm waves.

In the transitional Mamaia–Midia sector, exposure is double: while partially protected from southern waves, the beaches are strongly influenced by NE and SSE directions. This dual exposure explains the observed erosional–accretionary varieties and aligns with the “high vulnerability” CVI classifications assigned to these tourist beaches.

The southern coast (Constanța–Eforie–Mangalia) presents a different pattern, where cliff-based beaches and infrastructure act as localized barriers, creating shelter from southern waves. However, their orientation exposes them to NE and E events, resulting in alternating erosion and stability depending on groyne or breakwater configurations. The wave regime in this area interacts with anthropogenic structures, emphasizing the need for finer-resolution assessments (100 × 100 m) to capture local-scale variability.

Wave climate datasets for the Western Black Sea support these observations. Mean significant wave height (Hs) ranges between 0.7 and 1.2 m, with maximum storm Hs reaching 6–7 m under strong NE events [10,15,28,31,32]. Seasonal storminess peaks in winter, with ~20–25 storm days per year, and mean wave periods (Tz) vary between 4 and 6 s, extending beyond 8–9 s during storms. These values align with the exposure contrasts seen along the coast: the northern delta’s low-lying barriers are sensitive to long-period storm waves, while southern engineered beaches reflect a balance between exposure and human intervention.

The classification of wave exposure used for the CVI (Figure 7f) reflects these storm dynamics. The predominantly Very High Vulnerability ranking for wave exposure in the north is directly linked to the extensive, low-lying coastal barriers that are highly sensitive to long-period storm waves, as well as the low-gradient nearshore bathymetry (Figure 4a) which allows waves to propagate further inland. In contrast, the southern unit’s more varied exposure (Figure 7f) is enhanced by the steeper nearshore slope (Figure 4b, Table 2) and the presence of both natural cliffs and engineered structures, which modify wave action at the coastline.

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

However, the present assessment has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the spatial resolution of the CVI analysis (1 × 1 km grid)—while effective for broad regional patterns—is relatively coarse for capturing local-scale variations. In the heterogeneous and heavily engineered southern coastal sectors, this resolution inevitably smooths over fine-scale processes; localized erosion hotspots or the defending effects of small protective structures may be averaged out within a single grid cell. As a result, vulnerability in certain micro-environments could be under- or over-estimated. For instance, a short stretch shielded by a breakwater might still fall into a high-vulnerability cell if adjacent areas are eroding, and vice versa.

A second set of limitations concerns the temporal coverage of the datasets used in the CVI computation. The shoreline-evolution rates integrated into the index correspond to the period 2011–2020 for the northern unit, as shown in Figure 5, and to the 2014–2021 multitemporal shoreline dataset for the southern developed sectors shown in Figure 6. These intervals reflect the best available observational records, but they necessarily exclude shoreline adjustments associated with interventions, nourishment cycles, or episodic storm events that occurred after the latest year represented in each dataset. Similarly, the bathymetric profiles, wave-regime parameters, and sea level variability employed in the analysis reflect the measurement periods available in the institutional and published datasets described in Section 2 and therefore may not capture more recent or emerging hydrodynamic trends. Also, the bathymetric profiles used in this study reflect the conditions captured during the measurement campaigns (Figure 3 and Figure 4) and therefore do not include morphological adjustments that may have occurred after the dates of acquisition. The wave-regime parameters incorporated into the CVI (Section 3.2; Table 3) are derived from published datasets and in situ observations available for the periods covered by the referenced studies, meaning that potential changes in storm-wave characteristics in subsequent years are not represented. Sea level variability is integrated into the index as a long-term trend using values reported for the northwestern Black Sea in the cited literature (e.g., Medvedev et al., 2016 [21]; Mihailov et al., 2018 [22]), which describe rates within the range of approximately 1–3 mm/yr depending on the analyzed period. While these values are appropriate for representing historical and climatological conditions, they do not account for potential future accelerations or for localized vertical land-motion effects that may influence relative sea level trends at specific coastal segments.

Third, the semi-quantitative ranking procedure applied in this study introduces inherent uncertainty. As outlined in Section 2.1 and Table 1, continuous physical variables were transformed into ordinal classes on a 1–5 scale following established CVI methodologies [19,20]. While this approach ensures methodological comparability with previous coastal-vulnerability studies, it simplifies the underlying data. The use of discrete thresholds means that sensitive but significant differences in measured values may be grouped into the same class or separated into adjacent classes despite minimal numerical distinction. This constraint reflects the structure of the CVI itself, which provides a relative index of susceptibility rather than an exact quantitative measure. In addition, the variable set included in our tailored CVI was deliberately restricted to geophysical parameters—geomorphology, relief, substrate, coastal slope, shoreline-change rate, relative sea level trend, and wave regime—to assess physical vulnerability under the microtidal and morphodynamical conditions of the Romanian Black Sea coast. Socio-economic factors such as population density, critical infrastructure, land use, or exposure of built assets were not incorporated, in line with the study’s objective of producing an accurate physical vulnerability baseline. Therefore, the CVI highlights areas with high geomorphological sensitivity but does not evaluate the potential societal or economic consequences of coastal hazards. Thus, a coastal segment classified as “Very High” vulnerability in physical terms may host limited human activity, while a moderately vulnerable physical setting within a densely populated zone could face substantially higher overall risk. Integrating socio-economic indicators in future analyses would enable a more comprehensive, multi-dimensional assessment that captures both physical susceptibility and human exposure.

5. Conclusions

The NW Black Sea exhibits a highly dynamic sea level regime dominated by non-tidal processes. Short-term surges, seiches, and meteotsunamis frequently overshadow the microtidal signal. At the same time, long-term sea level rise represents a persistent risk with rates of 1–3 mm yr−1 depending on the period and correction applied. Seasonal cycles, strongly controlled by the Danube, support the importance of regional hydrological forcing in coastal dynamics.

Our findings confirm that astronomical tides are negligible compared to meteorological forcing in the NWBS. Moreover, historical storm surges along the western coast have exceeded 1.5 m. The seasonal cycle of mean sea level exhibits a robust annual amplitude of ~38 mm, primarily influenced by the discharge of the Danube River and evaporation–precipitation patterns. Long-term altimetric data reveal a basin-wide sea level rise of 2.5 ± 0.5 mm yr−1 since the early 1990s. However, corrected estimates that account for loading effects suggest an intrinsic trend of ~1 mm yr−1.

The study appropriately adapted the CVI to the unique hydro-geo-morphological conditions of this microtidal basin by excluding the tidal range variable and integrating key regional factors, including geomorphology, coastal slope, shoreline change rates, sea level, and wave regime.

The paper highlights an essential north–south opposition in coastal vulnerability. The northern unit, primarily composed of the Danube Delta, is intrinsically more vulnerable due to its low-lying terrain, unconsolidated sediments, and high exposure to energetic waves. The CVI results, validated by multi-decadal shoreline evolution data spanning over a century (Figure 9 and Figure 10), consistently classify this area as ‘Very High’ vulnerability. Specific hotspots—such as Sahalin, whose persistent westward migration is confirmed by shoreline analysis from 1898 to 2023 (Figure 10)—align perfectly with the model’s highest vulnerability scores. Moreover, the CVI’s low vulnerability assignment for Sulina Beach is validated by the long-term progradation observed in Figure 9, which features the sector’s stability to human-engineered structures and establishes the technical utility of the CVI in capturing the interaction between intrinsic coastal vulnerability and engineering-induced shoreline behavior.

In contrast, the southern unit presents a heterogeneous vulnerability pattern influenced by both natural and anthropogenic factors. While active cliffs provide stability and result in “Low” vulnerability scores, the sandy beaches and heavily developed tourist areas, such as Mamaia and Eforie, are categorized as “High” to “Very High” vulnerability. The CVI effectively captures how localized geodynamic conditions and the presence of coastal infrastructure—such as breakwaters and groynes—create a complex mosaic of erosion and stability.

The assessment represents a significant advancement in understanding northwestern Black Sea coastal dynamics, establishing a fundamental quantitative baseline in comparison to measured natural and anthropogenic factors. The work by Borzi et al. (2025) [39] highlights the need for diachronic analysis, a concept our work directly addresses through the validation against multi-decadal shoreline evolution (1898–2023), which is essential for capturing long-term geomorphological processes. While studies like Vadivel et al. (2025) [40] focus on innovative CVI applications with socioeconomic variables, our paper intentionally focuses on establishing a fundamental, high-confidence hydro-geo-morphological baseline at a regional scale.

Despite its effectiveness for a macro-scale assessment, a key limitation of the study is its 1 × 1 km grid resolution, which necessarily smooths over the highly localized processes in the southern developed sectors. Therefore, future research would focus on a nested analysis with a finer resolution, such as 100 × 100 m, to provide the detailed data needed for site-level decision support and to better assess the effectiveness of individual coastal defense structures. Furthermore, incorporating a wider range of socioeconomic variables, such as population distribution and tourism infrastructure, could provide a more comprehensive vulnerability assessment that accounts for human impacts on coastal risk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.-D.S., M.-E.M. and A.-C.C.; methodology, A.-D.S. and A.-C.C.; software, A.-D.S., M.-E.M. and A.-C.C.; formal analysis, A.-D.S., M.-E.M. and A.-C.C.; investigation, A.-D.S., M.-E.M., R.-D.N., D.M. and A.-C.C.; state-of-the-art investigation, A.-D.S., M.-E.M., R.-D.N., D.M. and A.-C.C.; resources, A.-D.S., M.-E.M., R.-D.N., D.M. and A.-C.C.; in situ data acquisition, A.-D.S., R.-D.N., D.M. and A.-C.C.; data processing, A.-D.S., R.-D.N., D.M. and A.-C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.-D.S., M.-E.M. and A.-C.C.; writing—review and editing, A.-D.S., M.-E.M. and A.-C.C.; visualization, A.-D.S. and A.-C.C.; supervision, M.-E.M.; funding acquisition, A.-D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Nucleu Programme SMART-BLUE 2023–2026 funded by the Ministry of Research, Innovation, and Digitization (grant numbers 33N/2023, PN23230101)—“Integrated model for spatial assessment of the marine and coastal environment vulnerabilities and adaptation of the socio-economic system to the cumulative impact of pressures-support in the implementation of maritime policies and the Blue Economy”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors. Data belongs to the National Institute for Marine Research and Development “Grigore Antipa”—NIMRD and can be accessed by the requirement to http://www.nodc.ro/data_policy_nimrd.php (accessed on 20 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CVI | Coastal Vulnerability Index |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| NIMRD | National Institute for Marine Research and Development “Grigore Antipa” |

| ESRI | Environmental Systems Research Institute |

| NUTS | Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics |

| CT | Constanta County |

| TL | Tulcea County |

| WBS | Western Black Sea |

| NWBS | Northwestern Black Sea |

| MSL | Mean sea level |

| Hs | Significant wave height, which represents the average of the highest one-third of waves |

| Tp | Peak wave period |

| NE | Northeast direction |

| SSE | South southeast direction |

| E | East direction |

| SE | Southeast direction |

| NW | Northwest direction |

| DTM | Digital Terrain Models |

References

- Loinenak, F.A.; Hartoko, A.; Muskananfola, M.R. Mapping of coastal vulnerability using the coastal vulnerability index and geographic information system. Int. J. Technol. 2015, 6, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanavati, E.; Shah-Hosseini, M.; Marriner, N. Analysis of the Makran Coastline of Iran’s Vulnerability to Global Sea-Level Rise. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A.I.A.; Din, A.H.M.; Yusof, N.; Abdullah, N.M.; Omar, A.H.; Abdul Khanan, M.F. Coastal vulnerability index development: A Review. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-4/W16, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Assessment of Coastal Zone Vulnerability in the Context of Sea Level Rise and Climate Change. In Sea Level Rise and Ocean Health in the Context of Climate Change; Zhang, Y., Cheng, Q., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, N.; Valchev, N.; Prodanov, B.; Eftimova, P.; Kotsev, I.; Dimitrov, L. Assessment of coastal receptors’ exposure vulnerability to flood hazard along Varna regional coast. Coast. Eng. Proc. 2017, 35, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazov, A.; Stanchev, H. Risks for the population along the Bulgarian Black Sea coast from flooding caused by extreme rise of sea level. Inf. Secur. Int. J. 2009, 24, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrau, J.; Alkaabi, K.; Bin Hdhaiba, S.O. Exploring GIS Techniques in Sea Level Change Studies: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajri, Z.; Beroho, M.; Lamhadri, S.; Ouallali, A.; Spalevi’c, V.; Aboumaria, K. Geomatics assessment of coastal erosion vulnerability: A case study of Agadir Bay, Morocco. J. Agric. For. 2024, 70, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergiev, S. Sea water flood resilience of five plant species with conservation status over the Bulgarian Black Sea coast. GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 16, 019–023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, M.; Beşiktepe, Ş.T. Mechanism of generation and propagation characteristics of coastal trapped waves in the Black Sea. Ocean Sci. 2022, 18, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, Z.N.; Popescu, I.; Mynett, A. The Niger Delta’s vulnerability to river floods due to sea level rise. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 14, 3317–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikova, A.V.; Argyriou, A.V.; Andriopoulou, N.C.; Alexandrakis, G.; Papadopoulos, N. Coastal Vulnerability of Archaeological Sites of Southeastern Crete, Greece. Land 2025, 14, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, M.; Biswas, S.; Mondal, B.; Pal, R. Coastal vulnerability assessment of the predicted sea level rise in the coastal zone of Krishna–Godavari delta region, Andhra Pradesh, East Coast of India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2015, 18, 1635–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, M.; Li, Y.; Tang, Z.; Cao, L.; Liu, X. Assessing hazard vulnerability, habitat conservation, and restoration for the enhancement of mainland China’s coastal resilience. Earth’s Future 2018, 6, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailov, M.E. The Black Sea Upwelling System: Analysis on the Western Shallow Waters. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendleton, E.; Thieler, E.; Williams, S. Coastal vulnerability assessment of National Park of American Samoa (NPSA) to sea-level rise 2005. In Open-File Report 2005-1055; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMODnet Bathymetry Consortium. EMODnet Digital Bathymetry (DTM); EMODnet Bathymetry Consortium: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimac, Z.; Lončar, N.; Faivre, S. Overview of Coastal Vulnerability Indices with Reference to Physical Characteristics of the Croatian Coast of Istria. Hydrology 2023, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornitz, V. Global coastal hazards from future sea level rise. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 1991, 89, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornitz, V. Vulnerability of the East Coast, USA to Future Sea Level Rise. JCR 1990, 9, 201–237. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44868636 (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Medvedev, I.P.; Rabinovich, A.B.; Kulikov, E.A. Tides in three enclosed basins: The Baltic, Black, and Caspian Seas. Front. Mar. Sci. 2016, 3, 180306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, D.L.; Johns, W.E.; Belonenko, T.V. Dynamic response of the Black Sea elevation to intraseasonal fluctuations of the Mediterranean sea level. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailov, M.E.; Buga, L.; Spinu, A.D.; Dumitrache, L.; Constantinoiu, L.F.; Tomescu-Chivu, M.I. Interconnection between Winds and Sea Level in the Western Black Sea Based on 10 Years Data Analysis from the Climate Change Perspective. Cercet. Mar. Rech. Mar. 2018, 48, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Rusu, L.; Raileanu, A.B.; Onea, F.A. Comparative Analysis of the Wind and Wave Climate in the Black Sea Along the Shipping Routes. Water 2018, 10, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Ye, J.; García-León, M.; Gràcia, V.; Ortego, M.I.; Stanica, A.; Sánchez-Arcilla, A. Multivariate Hybrid Modelling of Future Wave-Storms at the Northwestern Black Sea. Water 2018, 10, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedelcu, L.I.; Rusu, E. An Analysis of the Wind Parameters in the Western Side of the Black Sea. Inventions 2022, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]