Abstract

Land surface temperature (LST) is a key indicator reflecting the ecological environmental disturbance caused by open-pit coal mining activities and determining the ecological status in alpine permafrost regions. Thus, it is crucial to study the spatiotemporal variations and influencing mechanisms of LST throughout all stages of small-scale mining–large-scale land surface damage–ecological restoration. Landsat imagery over nine periods was extracted from the growing seasons between 1990 and 2024. This study retrieved LST while simultaneously calculating albedo, soil moisture, and normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) for each time phase. By integrating land use/cover (LUCC) data, the spatiotemporal evolution patterns of LST in the mining area throughout all stages were revealed. Based on the Geodetector method, an identification approach for factors influencing LST spatial differentiation was established. This approach was applicable to the entire process characterized by significant land type transitions. The results indicate that the spatiotemporal variations in LST were significantly correlated with land surface damage and restoration caused by human activities in the mining area. With the implementation of ecological restoration, high and ultra-high temperatures decreased by about 25.98% compared to the period when the surface damage was the most severe. The main influencing factors of LST differentiation were identified for different land use types, i.e., natural and restored meadows (soil wetness, albedo, and NDVI), mine pits (albedo, aspect, and elevation), and mining waste dumps (aspect and albedo before restoration; aspect and NDVI after restoration). This study can provide a reference for monitoring the ecological environment changes and ecological restoration of global coalfields with the same climatic characteristics.

1. Introduction

Mineral resource development has played an irreplaceable role in supporting social and economic development and industrialization [1]. However, large-scale open-pit mining, underground excavation, and metallurgical activities have inevitably led to various serious ecological environmental problems, such as topographic and geomorphological damage, loss of soil structure and fertility, water pollution, sharp biodiversity loss, landscape fragmentation, geological hazards, and dust pollution [2,3,4]. Even more seriously, coal is naturally found with impurities or gangue minerals like pyrite and quartz that could create by-products (e.g., ash) and various pollutants (e.g., CO2, NOX, SOX) [4]. These damages can directly degrade the service function of regional ecosystems, threaten ecological security, and pose long-term risks to the production, life, health, and well-being of the residents in and around mining areas. Especially in the high-altitude, cold and frozen soil areas where the ecological environment is highly sensitive and fragile, open-pit coal mining has further exacerbated the ecological environment problems. In order to restore and rebuild damaged ecosystems and their service functions, China has initiated ecological restoration projects (ERPs) of mines since the 1950s. Some progress has been made in the theory and practice of ecological restoration effect evaluation [5].

Early evaluations of ecological environment effects rely mainly on traditional manual field surveys. This method suffers from shortcomings such as low efficiency, high cost, and low spatiotemporal resolution. However, the rapid development of remote sensing technology provides strong technical support for comprehensively and quickly identifying environmental factors and monitoring environmental changes in mining areas [6,7]. Various remote sensing indices have been developed for monitoring vegetation damage in mining areas, such as normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) [8,9], fractional vegetation cover [10], enhanced vegetation index [11], normalized difference infrared index [12], and kernel normalized difference vegetation index [13]. In addition, ecosystem function indices based on satellite inversions have also been used to study regional ecological environmental changes and construct remote sensing ecological indices [14,15]. These ecosystem function indices mainly include soil wetness, soil temperature, soil dryness, total primary productivity of vegetation, and fraction of absorbed photosynthetically active radiation of vegetation.

Among many indices of ecological functions, land surface temperature (LST) is a significant parameter for both land surface energy and water balance studies. LST is also one of the most important indices to effectively measure ecological changes in plateau alpine mining areas [16]. Bhagat et al. found that the self-heating and spontaneous combustion properties of coal posed a serious challenge to mining areas, promoting LST and disrupting local ecosystems and climate change dynamics [17]. Jaiswal et al. investigated the impacts of coal mining on an area for more than two decades. They observed an increase in temperature in mining areas and neighboring urban areas [18]. This is attributed to mining expansion and deforestation. Li et al. conducted an ecological cumulative effect assessment in a mining area and determined that increasing mining activities significantly affected LST [19]. However, measures, such as ecological restoration and green mine construction, can slow down and stabilize the rate of LST changes. Similarly, Chaddad et al. investigated the effect of mining-induced deforestation on LST in mining areas of the Amazon rainforest and noted that LST increased by 10 °C over 15 years [20]. Meanwhile, LST indicators have extensively been employed to evaluate the ecological restoration of mines in arid and semi-arid environments [21,22]. Furthermore, some studies have also linked land use changes to changes in LST near mining areas [23,24,25,26]. LST data are also crucial in other research fields such as urban heat island, land cover, fire monitoring, agroforestry monitoring, and earthquake incubation [24,27,28].

However, for open-pit coal mines with high-altitude, cold, oxygen deficient, and permafrost climate characteristics, the ecological environment is sensitive and fragile. Ecological restoration is even more difficult due to mining-induced ecological damages [2]. Therefore, it is significant to effectively evaluate the changes in the ecological environment quality of this type of coal mining area and interpret its influencing factors for alleviating the human–nature conflict and achieving sustainable development of coal mining areas [6]. Regarding the issue of sustainable vegetation restoration in high-altitude mining areas, Jin et al. investigated the effects of restoration years under different artificial measures on vegetation and soil characteristics in the Muli Coalfield (2016–2020) [29]. Hong et al. conducted land cover and vegetation change monitoring in the Jvhugeng mining area from 2003 to 2021 using multi-source remote sensing data [30]. Yuan et al. used the typical high-altitude mining area of the Muli Coalfield in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau as an example. They analyzed the characteristics of regional ecological environment changes from 2003 to 2020 through remote sensing data, land use transfer matrix, landscape fragmentation index, and vegetation coverage [31]. Xiao et al. developed the Remote Sensing Ecological Index (RSEI) using the Muli Coalfield as the research object. They identified its temporal and spatial changes, and reconstructed and analyzed the time series changes in ecological environment quality from 2000 to 2020 [32]. LST is a key indicator of the ecological and environmental health status in high-altitude permafrost regions. However, there is currently relatively little research on using LST to monitor the ecological restoration effects in such characteristic environments. Moreover, few studies have analyzed in detail the spatiotemporal evolution of the ecological environment from mining to large-scale surface damage and ecological restoration. The impact of various factors on the ecological environment has rarely been identified accurately at different stages of mining and restoration in mining areas.

This study aims to make up the gap in existing research and provide better references for the ecological environment restoration of coalfields with plateau, alpine, hypoxic, and permafrost characteristics worldwide. This study took the Jvhugeng mining area of the Muli Coalfield as the study area. Nine periods of Landsat imagery were taken from the growing seasons between 1990 and 2024. In-depth research was conducted on the spatiotemporal changes and impact mechanisms of LST in the entire stages of small-scale mining, large-scale surface damage, and ecological restoration governance. By integrating land use/cover (LUCC) data, the spatiotemporal evolution patterns of LST in the mining area were revealed throughout all stages. Based on the Geodetector method, an identification approach for factors influencing LST spatial differentiation was established. This study is crucial for accurately reflecting the ecological environment changes and protection of open-pit coal mines in high-altitude permafrost regions. The organizational structure of this study is as follows: Section 1 provides a detailed discussion of the current research status of LST and introduces the key research content; Section 2 introduces the research area and data and proposes several remote sensing ecological indicator calculation methods, data analysis methods, and Geodetector models; Section 3 provides a detailed analysis of the spatiotemporal changes in LST before and after ecological restoration, as well as its response to LUCC; Section 4 discusses the mechanism of spatial heterogeneity in LST at different stages; Section 5 is the conclusion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

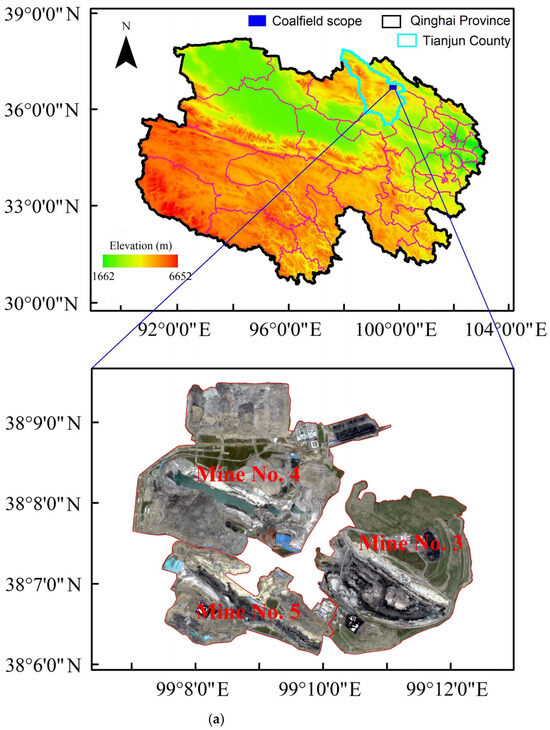

The Jvhugeng mining area of the Muli Coalfield is located in the upstream basin of the Datong River at the border of Haibei and Haixi in Qinghai Province and in the south-central part of the Qilian Mountains (Figure 1a). (The following text uniformly uses the Muli Coalfield as the representative of the research area.) Datong River is mainly supplied by atmospheric precipitation and snowmelt. The types of groundwater include frozen layer water and frozen layer groundwater, which are respectively replenished by precipitation and locally replenished by melting zones. The rivers that flow through the coal mining area mainly include Shangduosuo River and Xiaoduosuo River, both of which eventually merge into the Datong River (Figure 1b). In terms of geology in the mining area, from top to bottom, there are soil layers, seasonal frozen soil layers, and permanent frozen soil layers (Figure 1c). The soil layer includes the topsoil layer (TL), subsoil layer (SL), and parent material horizon (PMH). Coal seams are distributed in permanent frozen soil layers. The natural soil layer thickness in mountainous areas is only 20–50 cm, and mining in mining areas has turned the natural swamp wetland ecosystem into abandoned mining land, significantly reducing the ability of surface water conservation. The destruction of permafrost ecological geological layers in high-altitude permafrost regions has important control effects on topography, river and lake distribution, and vegetation distribution, with significant ecological effects.

Figure 1.

(a) Location and scope of the research area. (b) The elevation and hydrology of the coal mining area and its surrounding areas. (c) Schematic diagram of frozen soil layer construction in coal mining area.

Currently, research area has formed three sub mining areas, defined as Mine No. 3, Mine No. 4, and Mine No. 5. Its terrain shows a general trend of low in the southeast and high in the northwest. The topography of the study area is not undulating, with an altitude of 3800~4300 m. The Muli Coalfield is an important component of the Qilian Mountain water conservation area and ecological security barrier, with great significance for ecological protection. However, the long-term illegal mining activities in the Muli Coalfield have caused alarming ecological problems, such as widespread mine pits, accumulating slag heaps, unstable slopes, receding plateau meadows and wetlands, damage to permafrost and hydrological wetlands, waste of coal resources, and land desertification. These ecological problems have seriously damaged the ecological environment of the Qilian Mountains and the source of the upper reaches of the Yellow River. Due to the harsh climate and fragile ecological environment of the Muli Coalfield, the ecological environmental problems caused by past unorganized development activities are intertwined. In order to completely improve the environment of the mining area, high-intensity ecological restoration of the Muli Coalfield was initiated in 2020. Therefore, this study took the restoration area of the Muli Coalfield as the study area. Based on land use types, the spatiotemporal evolution and influencing mechanism of LST in all stages were investigated. This can help to assess ecological restoration effects and provide a basis for developing more reasonable and efficient ecological restoration measures.

2.2. Data Source

Landsat is one of the most widely used thermal infrared data because of its high spatial resolution and long-time continuous Earth observation. Therefore, in this study, nine scenes of Landsat 5 and Landsat 8/9 images covering the corresponding period were used for LST fine inversion of the mining area in the stages of pre-mining–maximum mining area–post-restoration (The image resolution is 30 m). The Landsat 5 and Landsat 8/9 images were obtained from the website of the U.S. Geological Survey (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov (accessed on 10 May 2025)). All Landsat images were obtained during the growing season, and their path/row was selected as 134/034 or 134/033. Coal mining in the Muli Coalfield began in the 1970s. Before 2002, the Muli Coalfield was in a small-scale mining stage, with the environment in a natural state. During 2002–2009, the Muli Coalfield was in a medium-to-low-scale mining stage. During 2009–2019, it was in a large-scale mining stage. Particularly, after the opening of the Hamu Railway in 2009, coal transportation became more convenient and easier, and the mining area expanded rapidly. Large-scale ERPs have been implemented since 2020. Based on the process of surface disturbance, the nine selected data dates were 30 August 1990, 15 August 2002, 23 August 2005, and 17 July 2009 (Landsat 5 image), 14 August 2019, 19 August 2021, 5 July 2022, 2 September 2023, and 27 August 2024 (Landsat 8 image) and 2 September 2023 (Landsat 9 image). These nine periods of data were divided into 1992–2009 (small-scale mining), 2010–2019 (large-scale mining), and 2020–2024 (ecological restoration). A new round of ERP started in the region in 2020. Thus, annual LST composites were obtained since 2019 in order to analyze the spatiotemporal variation characteristics of LST during ecological restoration in detail. The Landsat imagery in 2020 was not used in this study due to its large cloud cover. However, this study can still fully reflect the variation pattern of LST during ecological restoration in the mining area.

Landsat Collection 2 Level-2 Science Products (L2SP) and Landsat Collection 2 Level-1 Terrain Precision Correction (L1TP) were used in this study. L2SP was used to invert LST, extract LUCC and calculate NDVI. L1TP was used to calculate albedo and soil wetness index (WET) for the study area. To detect the SSH of LST, the SRTM Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data in the pre-mining period (2000) were obtained from the USGS website (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov (accessed on 15 May 2025)). Mine elevations, slope, and aspect were determined. The ASTER DEM V003 in the post-mining and post-restoration periods was obtained from EARTHDATA (https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/search/ (accessed on 16 April 2025)). Based on two images from different angles, EARTHDATA can combine stereo image pairs and photogrammetric surveying for elevation measurements. The data were collected on 19 April 2015, and 24 April 2021. The mining and restoration of the mining area significantly changed the topography. Therefore, this study used DEMs over three periods (pre-mining, post-mining, and post-restoration) to analyze the influence of topographic elements on LST at different development stages of the mining area.

2.3. Methods

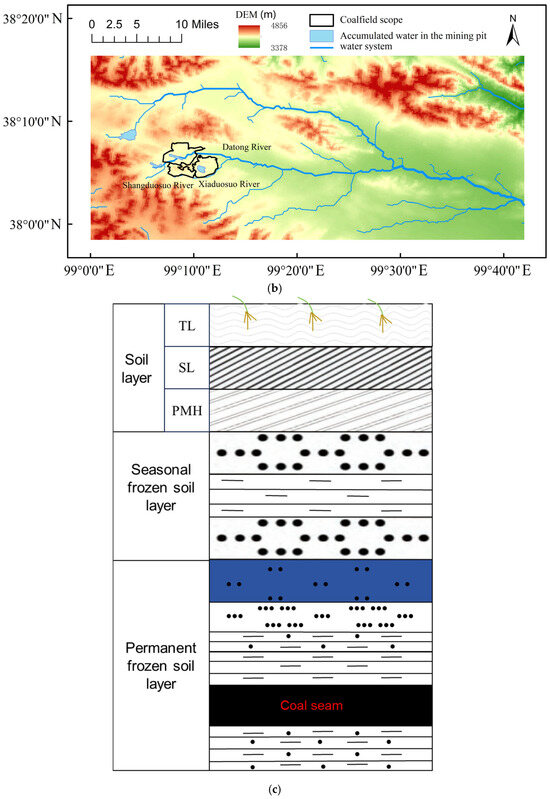

In order to clearly demonstrate the techniques and methods, the flowchart of the study is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Technical flowchart of the study.

2.3.1. Land Surface Temperature

LST inversion using Landsat satellite data involves multiple steps. The core principle is to utilize radiant energy detected in the thermal infrared band of satellite sensors to ultimately deduce true physical LST through surface emissivity and atmospheric correction. For Landsat 5 satellites with only one thermal infrared band, single-channel algorithms are commonly used for LST inversion, including the algorithm based on the radiative transfer equation, the single-window algorithm, and the generalized single-channel algorithm [33]. For Landsat 8/9 satellites with two thermal infrared bands, LST inversion can be performed using the split-window algorithm [34]. Differences in the response of two adjacent thermal infrared bands (typically Band 10 and Band 11) to atmospheric absorption (mainly water vapor) can exclude most atmospheric effects. This is an advantage of dual-band sensors, reducing dependence on atmospheric parameters relative to the single-channel method.

Whether utilizing the single-channel algorithm or the split-window algorithm, LST calculation is complex and requires multiple types of auxiliary parameters. To reduce the burden on users, the USGS conducted a second major reprocessing event of the Landsat archive to improve the product in terms of data processing, algorithm development, and data access. Therefore, the LST product provided by the L2SP dataset was used in this study for long time-scale analysis. The detailed acquisition process of LST is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Detailed acquisition processes of LST.

In order to evaluate the usability of LST provided by the L2SP dataset in the mining area, a relatively flat range with uniform surface properties was selected for cross validation. The average of four-pixel sized regions in MODIS was compared with LST resampled to 1 km using Landsat. The calculation results show that the average difference in LST between the two datasets was about 1.58 °C. This indicates that the L2SP dataset can be well used for studying the spatiotemporal changes and influencing mechanisms of LST in mining areas.

2.3.2. Albedo

Albedo can reflect LST changes due to mining and restoration activities. Thus, albedo can be used to explore the effects of different stages of mining and restoration on the LST. In this study, the conversion coefficient from narrow-band to wide-band albedo established by Liang et al. was used to calculate albedo. Assuming that the surface is a Lambertian surface, the spectral reflectance of Landsat can be regarded as the narrow-band albedo [35]:

where , , , , and are the reflectance for the blue, red, near-infrared (NIR), SWIR 1, and SWIR 2 bands of the Landsat data, respectively.

2.3.3. Normalized Difference Vegetation Index

NDVI is one of the most widely used and earliest remote sensing analysis tools for vegetation assessment. NDVI utilizes satellite data in the red and NIR bands to differentiate between vegetation and water based on the characteristics of high vegetation reflectance and low water reflectance in NIR spectra. NDVI has been proven to be effective in differentiating between forested and non-forested areas. It is mainly used to estimate parameters such as leaf area index, biomass, leaf chlorophyll content, vegetation productivity, vegetation cover, and vegetation stress. NDVI can be expressed as [36]:

2.3.4. Soil Wetness

WET is expressed using the wetness component of the tasseled cap transformation. This component is closely related to the moisture content of soil and vegetation and is an important index for monitoring land surface environments [37]:

where is the green band reflectance. Low wetness indicates serious land degradation, low vegetation cover, and low water conservation capacity. High wetness indicates sufficient soil moisture, dense land surface vegetation cover, high water conservation capacity, and good ecological environment. WET can be used to analyze the influence of different stages of mining and restoration on LST.

2.3.5. Variation Trend

In order to study the spatiotemporal dynamic patterns of NDVI and albedo and their correlations with time-varying temperature changes, the least-squares method was used to fit the variation trend of NDVI and albedo on a pixel-by-pixel basis [13]:

where is the slope; is the total number of years, set to 9 in this study; is the LST value in the ith year; is the year. The natural breaks method was used to divide the absolute value of into three intervals of high, medium, and low values. Then, the variation trend of LST was comprehensively determined according to the positive and negative signs and the magnitude of the absolute value. The rules are as follows: > 0 and the absolute value is in the high-value interval, indicating that LST significantly increases; > 0 and the absolute value is in the middle-value interval, indicating that LST slightly increases; the absolute value of is in the low-value interval, indicating that there is no significant change in LST; < 0 and the absolute value is in the middle-value interval, indicating that LST slightly decreases; < 0 and the absolute value is in the high-value interval, indicating that LST significantly decreases.

2.3.6. Geodetector

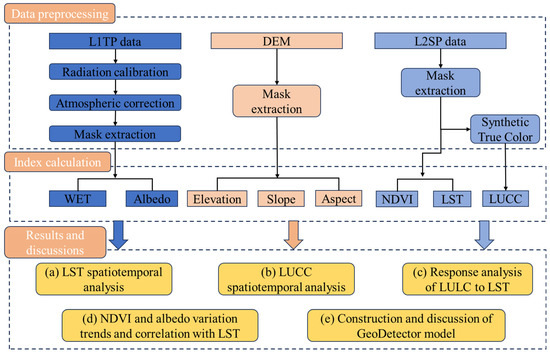

The topography of the Muli Coalfield changed significantly during the study period. In order to accurately identify the influencing factors of spatial differences in LST at different stages, this study developed a method for identifying factors influencing the SSH of LST that integrated NDVI, soil wetness, albedo, and topographic elements. Geodetector is a statistical method specialized in detecting the SSH of geographic phenomena and revealing its underlying driving forces. The differentiation and factor detection functions in GeoDetector were used to detect and quantify the extent to which NDVI, soil wetness, albedo, elevation, slope, and aspect explained the SSH of LST, which was measured by the q-value [38]:

where = 1, 2, 3, ...; is the number of strata of NDVI, soil wetness, albedo, elevation, slope, and aspect; and are the number of units in the stratum and the entire study area, respectively; and are the variance of LST in the stratum and the entire study area, respectively; and are the sum of the variance within the stratum and the total variance in the whole study area, respectively. The value range of q is 0 to 1. The larger q is, the greater the explanatory power of the independent variable on the spatial differentiation of the dependent variable. The reason for selecting the above indicators is that NDVI can well reflect the spatiotemporal differences in LST. Albedo is the main parameter reflecting the absorption of radiation energy by surface soil. The level of soil wetness impacts LST. Elevation, slope, and aspect can provide important information about terrain, climate, ecology, and other aspects, helping to better understand the relationship between the natural environment and human activities. The detailed process of constructing the Geodetector model is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Detailed processes of constructing the Geodetector.

3. Results

3.1. Spatiotemporal Variations of LST in the Mining Area Before and After Ecological Restoration

The image data used in this study ranged from 1990 to 2024 and were available for July, August, and September. LST was highly influenced by seasonal and meteorological factors during inversion. Therefore, in order to eliminate the influence of different years, months, and meteorological conditions, the method of mean minus standard deviation was used to divide LST into seven temperature classes, i.e., low temperature (LT), lower temperature (LeT), low–medium temperature (LMT), medium temperature (MT), sub-high temperature (SHT), high temperature (HT), and ultra-high temperature (UHT) [33]. This can increase LST comparability in different periods. The detailed classification criteria are shown in Table 2. is the LST of the pixel, is the average LST in the region, and is the standard deviation.

Table 2.

The classification criteria of LST.

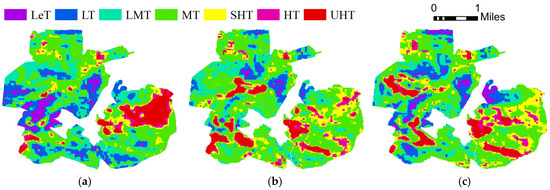

According to the LST classification criteria, Figure 4 shows the LST classification of the mining area for nine periods from 1990 to 2024. In order to facilitate the quantitative analysis of the spatiotemporal changes in LST in the mining area, the area share of each temperature class in each period is determined in Figure 5. The overall analysis shows that from 1990 to 2005, the LST of the mining area was mainly dominated by MT, LMT, LeT, and LT. The sum of the areas at these temperature classes accounted for 81.45%, 74.13%, and 72.80% of the total area in 1990, 2002, and 2005, respectively. At this time, the surface of the coal mining area was not extensively damaged and was basically covered by vegetation. The ecological environment was in the optimal state. With the increase in the mining range, the proportion of the area at the UHT class began to increase since 2009. The area at the UHT class was mainly distributed in the range of Mine No. 3, with scattered distribution in other areas. The area at the MT, LMT, LeT, and LT classes represented 65.41%, decreasing by about 16.04% relative to the pre-mining period (1990). The area at the HT and UHT classes accounted for about 21.14% of the total area, increasing by about 9.27% relative to the pre-mining period. By 2019 (with the most severe land surface damage), the area at the HT and UHT classes was the largest in the entire area (about 47.25%). The native vegetation was extensively damaged, and the ecological environment quality seriously decreased. Almost the entire area of Mine No. 3 was in the HT and UHT classes. The HT and UHT areas were mainly located in the southwest of Mine No. 5 and the north, southwest, and east of Mine No. 4. Over the two decades (1990–2019), LST in the mining area exhibited significant temporal variation characteristics and a strong autocorrelation with the mining progress of the coalfield at corresponding time points [39].

Figure 4.

Classification of LST in the study area from 1990 to 2024. (a) 1990; (b) 2002; (c) 2005; (d) 2009; (e) 2019; (f) 2021; (g) 2022; (h) 2023; (i) 2024.

Figure 5.

Proportion of area for each temperature level in each period.

Large-scale ecological restoration was implemented in the study area since August 2020. The treatment of mine pits was completed in December 2020. Grass planting and regreening began in April–May 2021. Therefore, in the context of ecological restoration, the LST classification results in the study area in 2021 dramatically changed relative to those in 2019. More notably, the SHT, HT, and UHT areas in the region significantly decreased, while the LT, LeT, LMT, and MT areas significantly increased. The improvement of LST was mainly because the vegetation regeneration function enhanced soil moisture restoration, promoting ecological environment quality. Figure 5 shows that the SHT, HT, and UHT areas accounted for about 32.10% of the total area, decreasing by about 36.30% relative to those in 2019. In 2021, the LT, LeT, LMT, and MT areas accounted for 67.90%, increasing by 36.31% relative to those in 2019. This indicates that ERPs can significantly improve regional temperature and enhance the ecological environment of the mining area. This is particularly important for improving the regional microclimate. The overall analysis indicates that, among the seven temperature classes, the LMT, MT, and HT areas exhibited the most significant improvement after ecological restoration, i.e., 11.78%, 11.66%, and 15.66%, respectively. This further demonstrates that vegetation restoration in the area after ecological restoration enhanced soil moisture restoration and water retention function.

The analysis of the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of LST after the implementation of the ERP (2021–2024) shows that the UHT and HT areas in the region increased in 2022, especially with the most pronounced increase in the range of Mine No. 4. This is mainly because the growth and distribution of plants might fluctuate in the early stage of vegetation restoration. These fluctuations represented an innate regulatory mechanism as part of the natural adaptation of plants to new environments [1]. The sum of the UTH, HT, and SHT areas accounted for 53.54% and 32.10% of the total area in 2022 and 2021, respectively. In 2023 and 2024 after the ecological restoration, the UHT, HT, and SHT in the region decreased, with their sum accounting for about 37.71% and 35.44% of the total area, respectively. This may be mainly related to increased vegetation adaptability to the environment and improved soil quality. In 2021 and 2024, the areas at the seven temperature classes were consistent, particularly with a difference of 0.26% and 1.59% between these two periods in the HT and UHT areas, respectively. However, there are still some difficulties in restoring the original ecological temperature in 1990. It is necessary to continue to promote ERPs.

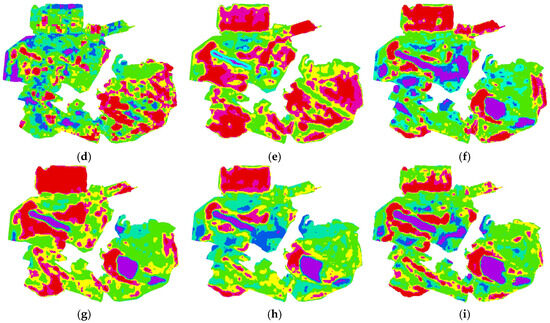

In order to analyze the LST variability at different temperature classes in the same year, the median temperature values of all raster temperatures under each temperature class are summarized in Figure 6. To assess changes in the difference between the maximum and minimum temperatures in the mining area for the nine periods, the LTs were subtracted from the UHTs. In addition, due to the influence of meteorological and seasonal factors, the raw temperatures in each period were not comparable. In contrast, the difference between the UHT and LT of each period was comparable. This is because there were water bodies in the mining area after 2021, i.e., the LUCC at the LT were water bodies. There were almost no water bodies in the land use types at the LT before 2021. Therefore, UHT minus LT was used to ensure that the data were comparable between different periods. Statistics show that the differences in UHT and LT in 1990, 2002, 2005 and 2009 were 6.77 °C, 7.69 °C, 7.18 °C, and 5.03 °C, respectively. The differences in UHT and LT in 2019, 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024 were 10.93 °C, 6.77 °C, 9.96 °C, 9.97 °C, and 9.56 °C, respectively. The UHT before mining differed from the LT by only 5–7 °C. This indicates that LST was relatively uniform throughout the region, without areas of larger LST. At the stages of mining at the highest intensity and ERPs, the difference between UHT and LT was about 10 °C. This indicates that there might be significant temperature fluctuations or extreme temperature conditions in the study area.

Figure 6.

The median temperature value of all grid points at each temperature level.

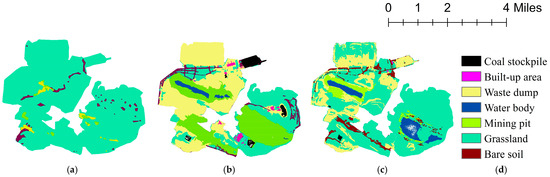

3.2. Spatiotemporal Variations of LUCC

According to the time points of mining and restoration in the mining area, an object-oriented classification method was used to extract the LULC data of the study area in the three periods of 1990, 2019, and 2024. Firstly, the image was segmented into meaningful image objects based on spectral heterogeneity between pixels. Then, the image objects were categorized based on the feature space. Finally, the LULC of the study area was classified into seven types, including mining pit, waste dump, coal yard, built-up area, grassland, water body, and bare soil (Figure 7). Grassland included artificial grassland, alpine meadow, and alpine swamp meadow. Artificial grassland refers to vegetation established during ERPs. Mining waste dumps are places used for centralized disposal of mining wastes.

Figure 7.

LULC types in the research area. (a) 1990; (b) 2019; (c) 2024; (d) LULC type.

During 1990–2019, the native alpine swamp meadow and alpine meadow in the mining area showed a continuously decreasing trend from 28.74 km2 (94.09% of the total area) in 1990 to 7.7 km2 (25.84% of the total area) in 2019 (Figure 7). The LULC types in 2019 and 1990 show that native meadows were mainly converted into mine pits and waste dumps, accounting for 27.08% and 36.97% of the total area, respectively. Built-up areas and coal yards also continued to increase, covering 0.36 km2 and 0.90 km2 by 2019, respectively. The coal yards were concentrated in the northeast of Mine No. 4. With the ERP, the areas of mine pits, mining waste dumps, built-up areas, and coal yards in the study area were gradually reduced. By 2024, the areas of the four LULC types were 1.49 km2, 6.46 km2, 0.01 km2, and 0.07 km2, decreasing by 81.5%, 41.4%, 96.0%, and 92.4% relative to 2019, respectively. Since ecological restoration, 62.6% of the artificial grasslands were regreened with vegetation, with the area reaching 18.66 km2. This indicated an increase of 141.6% relative to that in 2019. In addition, a large amount of mining pit stagnant water was formed. The area of the water body continued to increase from 0.53 km2 in 2019 to 1.62 km2 in 2024.

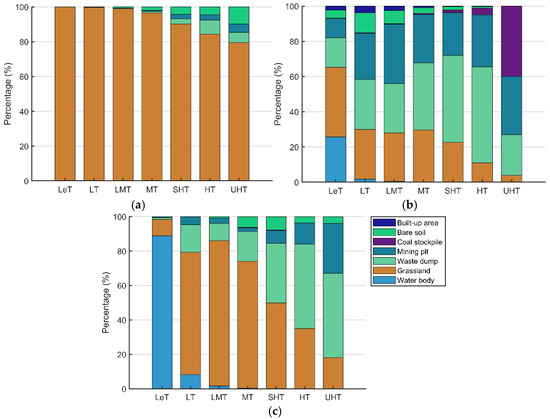

3.3. Response of Spatiotemporal Variations of LULC to LST

Changes in LULC types are an important influencing factor on the LST variations in the study area. When the mining area was in the natural stage, the LULC were mainly dominated by alpine meadows and alpine swamp meadows (Figure 8a,b). The LST of natural meadows showed a significant differential distribution, occupying a certain proportion at each temperature class. In 1990, the dominant LULC at each temperature class was natural meadow, especially at the LeT, LT, and LMT classes. With mining and land surface vegetation damage, the area of natural meadows reached the minimum in 2019. The meadows were indirectly affected by mining in some way, and vegetation degradation occurred [39]. Natural meadows were presented at each temperature class, mainly concentrated at the LeT, LT, LMT, and MT classes (39.47%, 28.16%, 27.46%, and 29.45%, respectively). In 2020 after the restoration, the mining area was mainly dominated by artificial grassland. As shown in Figure 8c, artificial grassland accounted for a smaller proportion at the LeT and UHT classes (9.61% and 18.15%, respectively), and was mainly distributed at the LT, LMT, and MT classes (71.06%, 84.29%, and 73.63%, respectively). It can be clearly seen that there was a significant correlation between LST and LUCC. Before ecological restoration, the changes in LUCC were caused by surface vegetation degradation and the conversion into relatively HT mining pits and waste dumps. The core task of ERPs was vegetation greening, which involves soil improvement and grass planting in waste dumps, mines, and coal yards.

Figure 8.

Response of LST to LULC. (a) 1990; (b) 2019; (c) 2024.

Coal mine LULC, such as mine pits, waste dumps, and coal yards, had relatively high LST in most areas. With mining expansion, these three land types gradually replaced natural meadows as the main source of SHT, HT, and UHT areas. Regarding the UHT in Figure 8b, the main LULC were coal yards, mine pits, and waste dumps, accounting for 39.88%, 33.16%, and 23.06%, respectively. In the HT and SHT areas, waste dumps and mine pits still represented a large proportion. The statistics show that waste dumps occupied 54.55% and 29.63% at the HT and SHTT classes, respectively. Mine pits accounted for 49.41% and 24.25% at the HT and SHTT classes, respectively. This proves that high LST in the mining area was attributed to the occurrence of LULC types such as mine pits, waste dumps, and coal yards. In addition, waste dumps and mine pits also occupied a certain proportion in the MT, LMT, and LT areas. This is attributed to the ability to receive solar radiation under different aspects, according to the SSH results of Geodetector below. With the implementation of the ERP, the area of mine pits, waste dumps, and coal yards in the study area significantly decreased. In contrast, the area of artificial grassland significantly increased. As shown in Figure 8c, the main LULC type in the LT, LMT, MT, and SHT areas was converted to artificial grassland. Relative to those in 2019, mine pits decreased by 21.61%, 30.96%, 25.54%, 16.80%, and 17.29% at the five temperature classes, respectively. Waste dumps decreased by 12.42%, 17.76%, 20.79%, 14.72%, and 5.47% in these temperature classes, respectively. This once again demonstrates that after ecological restoration, vegetation in coal mining areas underwent greening, and soil moisture recovery and water retention functions were enhanced. In Figure 8c, the main LULC types causing UHT were mine pits and waste dumps. The proportion of waste dumps showed an increasing trend relative to 2019. This is mainly because coal yards were partially converted to grasslands and waste dumps after restoration. Therefore, the core of the ecological restoration and management is to manage mine waste dumps in order to further reduce regional LST.

In 2019 with the most severe land surface damage in the mining area and 2024 after restoration, the water bodies presented LeT and LT. The area of the water bodies increased with ecological restoration and accounted for 25.73% and 88.83% of the LeT area in 2019 and 2024, respectively. The expansion of water bodies played an important role in promoting vegetation growth, regulating regional climate, and improving the ecological environment.

In summary, human activities in the mining area altered the original land use patterns, resulting in changes in LST. These activities also caused certain disturbances to the ecological environment and surface energy balance of the mining area. LST has extensively been investigated in mining areas worldwide. Firozjaei et al. [40] evaluated the historical impact of mining activities on surface biophysical features at the Sungun mine in Iran, the Asabaska oil sands in Canada, the Singrauli coalfield in India, and the Hambach mine in Germany. They predicted future changes in vegetation cover and LST models. Owolabi et al. [41] analyzed the spatiotemporal changes in LST, land and water resources of host communities caused by artisanal and small-scale mining in three mining areas in Nigeria. In addition, some studies focused on analyzing the correlation between LST and biophysical parameters (e.g., NDVI, NDWI, and NDBI), the impact of landscape pattern on LST, and the spatiotemporal distribution and variation characteristics of coal fires [42]. The research areas are located in the Jharia Coalfield in India and the Uda Coalfield in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. Due to the climate characteristics of high altitude, cold, and oxygen deficiency, the ecological environment of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau is sensitive and more fragile. The damage caused by coal mining to the ecological environment is even more difficult to restore. Focusing on the Muli Coalfield, this study conducted in-depth research on the spatiotemporal changes and impact mechanisms of LST during the entire stages of small-scale mining, large-scale surface damage, and ecological restoration. This can help to accurately reflect the changes in the ecological environment of coal mines under such climatic conditions, addressing limitations of using LST to study the characteristics of changes in the ecological environment of coal mines in high-altitude, cold and hypoxic environments.

3.4. NDVI and Albedo Variation Trends and Their Correlation with LST

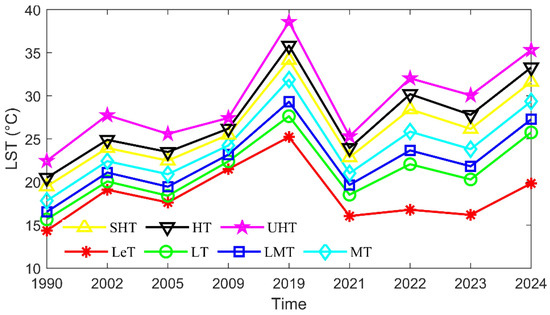

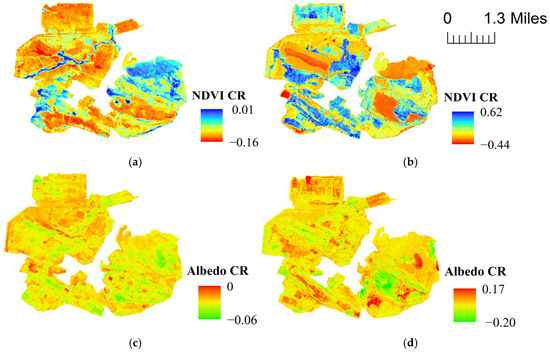

Mining and restoration activities in mining areas induced drastic changes in NDVI and albedo, which were strongly correlated with the SSH of LST. Therefore, this section focuses on examining the variation trends in NDVI and albedo. 2019 was the division time point of the most serious land surface damage and the beginning of large-scale ecological restoration in the mining area. Therefore, the variation trends of NDVI and albedo during 1990–2019 and 2019–2024 were calculated based on the least squares pixel-by-pixel fitting method. Before 2009, the mining area was in small-scale mining, with insignificant land type conversion. A time interval of five years was used in the study to determine the variation trends (Figure 9). It is worth noting that NDVI and albedo are indices reflecting the ecological environment, and the units are not given.

Figure 9.

Variation trends of NDVI and albedo. (a) NDVI trend from 1990 to 2019; (b) NDVI trend from 2019 to 2024; (c) albedo trend from 1990 to 2019; (d) albedo trend from 2019 to 2024.

Figure 9a shows that NDVI values decreased from 1990 to 2019 due to vegetation damage by human activities in the mining area. Most areas exhibited a decrease ranging from −0.09 to −1.6 every five years. These areas were mainly distributed in the whole area of Mine No. 4, the central and southern part of Mine No. 3, and the central and eastern part of Mine No. 5. After the ecological restoration, regional NDVI showed a significant upward trend, with an increasing rate ranging from 0. 28 to 0.62 every five years. The most pronounced effects occurred in the entire area of Mine No. 5 and the area of Mine No. 4 excluding mine pits and water bodies. In the north of Mine No. 3, the natural meadows showed a slight downward trend (by about −0.04 every five years) during 2019–2024, mainly due to vegetation degradation in this area. Combined with the results of temperature classification in 2019 and 2024 (Figure 4), the analysis indicates that the regions with significant decreasing and increasing variation rates of NDVI corresponded to the regions with the highest and lowest temperatures, respectively. Therefore, the spatiotemporal changes of NDVI play an important role in identifying and analyzing the SSH of LST.

Similarly to the NDVI variation trend, Figure 9c shows that most areas exhibited a significant decreasing trend in albedo from 1990 to 2019, with a decreasing rate ranging from −0.06 to 0 every five years (about −0.04 on average). After restoration, most areas restored by planting grasses showed a significant increase in albedo, with a maximum rate of up to 0.17 every five years. In addition, newly constructed water bodies within the mining area showed a decreasing trend in albedo. Higher surface albedo led to greater reflection of solar radiation and lower LST. Thus, the increasing trend of LST from 1990 to 2019 and the decreasing trend of LST from 2019 to 2024 were strongly correlated with the spatiotemporal changes in albedo. Spatial distribution heterogeneity in LST occurred under inconsistent variation trends of albedo.

4. Discussion

The influencing mechanism of the SSH of LST was investigated at different stages of pre-mining, mining at the highest intensity and post-restoration. The influencing factors, such as NDVI, soil wetness, albedo, slope, aspect, and elevation, were extracted at each stage based on the classification of LULC types in 2019. Soil wetness was calculated according to Equation (4). Taking LST as the dependent variable, the explanatory ability of each influencing factor on LST was investigated based on the differentiation and factor detection functions of Geodetector (Table 3). It is worth noting that coal yards, built-up areas, bare lands, and water bodies were not included in this study because of their small areas and concentrated spatial distributions.

Table 3.

Geographical detection results of factors affecting LST.

The q-values show that soil wetness, albedo, and NDVI had much larger explanatory abilities for LST than aspect, elevation, and slope in the natural meadows in 1990. The natural meadows were mainly alpine swamp meadows and alpine meadows. Thus, the SSH of their LSTs was mainly determined by the characteristics of these two meadow types. According to Guo et al., alpine swamp meadows have better vegetation growth and lower LST due to higher water content and lower albedo [39]. In contrast, alpine meadows have lower soil moisture content, suppressed vegetation growth, and thus higher LST. Therefore, in the meadow area, aspect, elevation, and slope had a lower explanatory ability for LST. Contrarily, soil wetness, albedo, and NDVI presented a stronger explanatory ability. In 2019, the land surface of the mining area was extensively damaged, and consequently grassland degradation occurred. Albedo, aspect, and elevation became the main factors affecting the SSH of LST of the grassland. With the implementation of the ERP, soil wetness, albedo, and NDVI were the main factors affecting the SSH of LST of the grassland. They were the same as those affecting the natural grassland, with a lower explanatory ability than that in 2019. Therefore, in order to further reduce the LST of grassland, soil wetness, and vegetation growth should be promoted, in turn enhancing albedo.

Albedo, aspect, and elevation were the main factors affecting the SSH of LST in the mine pit before and after ecological governance. This is because, under the bare surface, sunny slopes received greater solar radiation input, leading to elevated LST. However, shady slopes exhibited diminished radiation receipt and, consequently, lower LST, which is the main factor causing spatial differences in LST in mining areas [33,39]. It is evident that the explanatory power of NDVI in the mining pit decreased after ecological restoration. This is because the main measure taken during restoration was to level the terrain of the mine pit, and vegetation restoration was insignificant. For waste dumps, aspect was also the main factor influencing the SSH of LST, with its explanatory ability reaching 0.174 and 0.185 in 2019 and 2024, respectively. However, there was a difference between 2019 and 2024, i.e., albedo was the second factor influencing the SSH of LST of waste dumps in 2019. After compaction, the surface soil of the waste dump increased in density, resulting in an increase in surface reflectance and surface evaporation. This led to a decrease in soil moisture content and an increase in surface temperature. In 2024, NDVI became the second factor influencing the SSH of LST of waste dumps. Vegetation cover significantly increased in the waste dumps after ecological restoration. NDVI and albedo were closely related to vegetation growth, exhibiting a stronger explanatory ability. The above analysis indicates that different strategies should be utilized to regulate various types of influencing factors at different stages of mining and restoration in order to reduce LST.

Based on the actual geographical environment of different mining areas, indicators that can reflect the ecological environment of coal mining areas and their driving forces have been investigated. For example, Li et al. [43] analyzed the spatial differentiation impact mechanism of land desertification based on the mining history of the Lingnan rare earth mining area (located in southern China), including terrain, soil, meteorology, vegetation, and human activities. The results indicate that vegetation coverage had the highest explanatory power for the distribution of desertification in mining areas, followed by land use classification. Nie et al. [44] used an ecological environment quality regression model to confirm that climate change had limited impacts on the ecological environment quality of the Yangquan coal mining area (arid semi-arid). Coal mining activities, land reclamation and ecological restoration, and urbanization construction were the main influencing factors of ecological environment quality changes. Li et al. and Nie et al. showed that human activities were the main cause of ecological environment changes and spatial differentiation in mining areas, which is consistent with the conclusions of this study. For the entire stage of surface disturbance in the Muli Coalfield, human factors also played a very important role. These impacts included extensive degradation and restoration of vegetation, formation and leveling of mining pits and waste dumps. Furthermore, these changes altered the aspect of the terrain and the intensity of solar radiation received. In addition, the explanatory power of elevation on the spatial differentiation of LST cannot be ignored. This may be related to the high altitude and hypoxic environment of the study area, further enhancing the amount of solar radiation. The evidence that this human activity is the main cause of ecological environment changes and spatial differentiation in mining areas can also be found in Haikou Phosphate Mine [45], the Heidaigou open-pit coal mine [2], and the Shendong coal mine [13].

5. Conclusions

This study took the Muli Coalfield restoration area as the study area. This area was characterized by alpine, arid, and anoxic climate. The LST, albedo, soil wetness, and NDVI were inverted and acquired based on Landsat 5/8/9 remote sensing images in the nine growing seasons from 1990 to 2024. The spatiotemporal dynamic evolution characteristics of LST in the mining area were analyzed in combination with LUCC data in the whole stage of small-scale mining–large-scale surface damage–ecological restoration. Based on Geodetector, a method of identifying factors influencing the SSH of LST in all stages was developed, and it was applicable to significant shifts in land use types before and after ecological restoration. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The spatiotemporal changes in LST in the mining area were significantly influenced by human activities. The LST of the mining area in 1990–2005, which was basically in the natural state, was mainly dominated by MT, LMT, LeT, and LT. The total area of these temperature levels exceeded 74%. By 2019, when the land surface was subjected to the most serious damage, the area at the HT and UHT classes occupied the largest proportion (about 47.25%). With the implementation of the ERP, the area at the HT and UHT classes accounted for about 21.27% of the total area by 2024, decreasing by about 25.98%.

(2) The object-oriented approach was utilized to obtain LUCC data for the three stages of pre-mining–mining at the highest intensity–ecological restoration. Natural meadows decreased from 28.74 km2 in 1990 to 7.7 km2 in 2019. The meadows were mainly converted into mine pits and waste dumps, which accounted for 27.08% and 36.97% of the total area, respectively. Since the ecological restoration, 62.6% of vegetation regreening was realized in the artificial grassland area.

(3) Influenced by soil wetness and albedo, the LST of natural meadows was differentially distributed and occupied a certain proportion at each temperature class. By 2019, the area of natural meadows reached the minimum. Natural meadows were indirectly affected by mining to some extent, and vegetation degradation occurred. The temperature classes were mainly concentrated at LeT, LT, LMT, and MT with a low proportion. After the special projects addressing ecological degradation, artificial grasslands were mainly distributed in the LT, LMT, and MT areas. With the implementation of the ERP, the temperature of the mine pit and waste pile was reduced to 5–31%.

(4) The main influencing factors of LST differentiation were identified for different LUCC types, i.e., natural and restored meadows (soil wetness, albedo, and NDVI), mine pits (albedo, aspect, and elevation), and mining waste dumps (aspect and albedo before restoration; aspect and NDVI after restoration).

(5) For global mining ERPs, establishing a full cycle remote sensing monitoring system from pre-mining to mid-mining and post restoration can effectively evaluate the ecological restoration effect and analyze influencing factors. It is necessary to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of ecological restoration effects using multiple indicators such as LST, NDVI, albedo, and soil wetness. Our research shows that LST was highly correlated with human activity intensity, with HT areas concentrated in mining pits and waste dumps. After restoration, the HT area significantly decreased. Therefore, ERPs should focus on these areas. Targeted restoration measures should be adopted based on different LUCC types and their impact mechanisms on LST.

This study obtained Landsat images used in LST due to its advantage of a long time span. However, with a resolution of 30 m, its ability to capture spatiotemporal changes and analyze subtle features of LST influence mechanisms is insufficient. On this basis, it is necessary to introduce various satellite sensor data, such as MODIS, Sentinel, and high-resolution series. The spatiotemporal and spectral resolutions of remote sensing images need to be improved through multi-source remote sensing data fusion technology. In addition, this study preliminarily identifies areas in the Muli Coalfield where LST has been significantly affected by human activities. It is necessary to further investigate the specific types, intensities, and frequencies of human activities and explore their exact correlations with LST changes in order to deeply analyze this impact mechanism. A direct application of this study is to monitor the ecological restoration effectiveness of different restoration modes through LST, guiding increasingly difficult ERPs. For example, in current research, it has been found that waste dumps and mining pits are still the main sources of LST. Reasonable ERPs should be implemented based on soil physical and chemical characteristics, terrain features, and ecological degradation characteristics for these two land use types.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C. and L.J.; methodology, L.C.; software, C.Y.; validation, J.L. and S.J.; formal analysis, L.J.; investigation, Y.Z.; resources, X.Y.; data curation, C.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, L.J. and L.C.; writing—review and editing, C.Y.; visualization, X.Y.; supervision, Y.Z.; project administration, S.J.; funding acquisition, L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFF1303305), Science and Technology Innovation Project of China Coal Geology Administration (ZMKJ-2023-GJ02), open Fund of State Key Laboratory for Fine Exploration and Intelligent Development of Coal Resources (SKLCRSM24KFA12), and Ministry-Province Cooperative Project under the Ministry of Natural Resources (2024ZRBSHZ098).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The Landsat 5 and Landsat 8/9 images are available at https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov (accessed on 10 May 2025). The SRTM Digital Elevation Model data in the pre-mining period (2000) is obtained from https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov (accessed on 15 May 2025). The ASTER DEM V003 in the post-mining and post-restoration periods is obtained from https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/search/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, S.; Li, X. Several basic issues of ecological restoration of coal mines under background of carbon neutrality. Coal Sci. Technol. 2022, 50, 286–292. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.; Niu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Han, Y.; Dong, J.; Zhang, J. Impacts of mining on landscape pattern and primary productivity in the grassland of Inner Mongolia: A case study of Heidaigou open pit coal mining. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2014, 34, 2855–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ma, C.; Ma, Y.; Li, T. Monitoring and evaluation of ecological restoration in open-pit coal mine using remote sensing data based on a OM-RSEI model. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2025, 600–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phengsaart, T.; Srichonphaisan, P.; Kertbundit, C.; Soonthornwiphat, N.; Sinthugoot, S.; Phumkokrux, N.; Juntarasakula, O.; Maneeintra, K.; Numprasanthaia, A.; Parkb, I.; et al. Conventional and recent advances in gravity separation technologies for coal cleaning: A systematic and critical review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Ouyang, J.; Zheng, S.; Tian, Y.; Sun, R.; Bao, R.; Li, T.; Yu, T.; Li, S.; Wu, D.; et al. Research on Ecological Effect Assessment Method of Ecological Restoration of Open-Pit Coal Mines in Alpine Regions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 7682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Song, W.; Gu, H.; Li, F. Progress in the remote sensing monitoring of the ecological environment in mining areas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Shi, Y.; Fu, Y. Identifying vegetation restoration effectiveness and driving factors on different micro-topographic types of hilly Loess Plateau: From the perspective of ecological resilience. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 289, 112562–112576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Ye, B.; Bai, Z.; Feng, Y. Remote sensing monitoring of vegetation reclamation in the Antaibao open-pit mine. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Huang, J.; Lei, S.; Cao, Z. Study on vegetation coverage change of Xilinhot’s Shengli mining area in recent 30 years. J. Henan Polytech. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2019, 38, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zahidi, I.; Liang, D. Spatiotemporal variation of vegetation cover in mining areas of Dexing City, China. Environ. Res. 2023, 225, 115634–115643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karan, S.; Samadder, S.; Maiti, S. Assessment of the capability of remote sensing and GIS techniques for monitoring reclamation success in coal mine degraded lands. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 182, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yan, X.; Cao, Z.; Yang, Z.; Liang, J.; Ma, T.; Liu, Q. Identification of successional trajectory over 30 years and evaluation of reclamation effect in coal waste dumps of surface coal mine. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 269, 122161–122174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jiao, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H. Investigating the spatio-temporal pattern evolution characteristics of vegetation change in Shendong coal mining area based on kNDVI and intensity analysis. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1344664–1344684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Y. Response of net primary productivity of vegetation to land cover change in six coal fields of Shanxi province. China Min. Mag. 2021, 30, 107–114. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Ma, G. Soil erosion changes in Jiangxi Province from 2001 to 2015 based on USLE model. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2018, 38, 8–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guha, S.; Govil, H.; Gill, N.; Dey, A. A long-term seasonal analysis on the relationship between LST and NDBI using Landsat data. Quatern Int. 2020, 575–576, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, S.; Prasad, P. Assessing the Impact of Spatio-Temporal Land Use and Land Cover Changes on Land Surface Temperature, with a Major Emphasis on Mining Activities in the State of Chhattisgarh, India. Spat. Inf. Res. 2024, 32, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, T.; Jhariya, D.; Kishore, N. The Effects of Coal Mining on Land Use and Land Surface Temperature: A Case Study of Korba District, Chhattisgarh. J. Environ. Inform. Lett. 2023, 10, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Guo, J.; Wang, F.; Song, Z. Monitoring the Characteristics of Ecological Cumulative Effect Due to Mining Disturbance Utilizing Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaddad, F.; Mello, F.; Tayebi, M.; Safanelli, J.; Campos, L.; Amorim, M.; de Sousa, G.; Ferreira, T.; Ruiz, F.; Perlatti, F. Impact of Mining-Induced Deforestation on Soil Surface Temperature and Carbon Stocks: A Case Study Using Remote Sensing in the Amazon Rainforest. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 2022, 119, 103983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimish, G.; Bharath, H.; Lalitha, A. Exploring Temperature Indices by Deriving Relationship Between Land Surface Temperature and Urban Landscape. Remote Sens. Appl. 2020, 18, 100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Li, C.; Liu, X.; Zhao, X. Assessing Ecological Restoration in Arid Mining Regions: A Progressive Evaluation System. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, Q.; Yu, W.; Liang, S. Determining the scale of coal mining in an ecologically fragile mining area under the constraint of water resources carrying capacity. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 279, 111621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqi, J.; Yuhong, W. Effects of Land Use and Land Cover Pattern on Urban Temperature Variations: A Case Study in Hong Kong. Urban Clim. 2020, 34, 100693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Gupta, K. Urban Heat Island Formation in Relation to Land Transformation: A Study on a Mining Industrial Region of West Bengal. In Regional Development Planning and Practice: Contemporary Issues in South Asia; Mishra, M., Singh, R.B., Lucena, A.J., de Chatterjee, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 297–323. ISBN 978-981-16-5681-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kandulna, W.; Jain, M.; Chugh, Y.; Agarwal, S. Spatial Variability of Land Surface Temperature of a Coal Mining Region Using a Geographically Weighted Regression Model: A Case Study. Land 2025, 14, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudriki Semlali, B.E.; Molina, C.; Park, H.; Camps, A. Fengyun-2F/VISSR Land Surface Temperature Anomalies Between 2014 and 2022 and Their Potential Correlation with Earthquakes. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2023-2023 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Pasadena, CA, USA, 16–21 July 2023; pp. 2560–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudriki Semlali, B.E.; Molina, C.; Park, H.; Camps, A. Association of land surface temperature anomalies from GOES/ABI, MSG/SEVIRI, and Himawari-8/AHI with land earthquakes between 2010 and 2021. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2024, 15, 2324982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Li, X.; Sun, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Effects of Restoration Years on Vegetation and Soil Characteristics under Different Artificial Measures in Alpine Mining Areas, West China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, F.; He, G.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, Y. Monitoring of Land Cover and Vegetation Changes in Juhugeng Coal Mining Area Based on Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Hu, Z.; Yang, K.; Guo, J.; Li, P.; Li, G. Assessment of the Ecological Impacts of Coal Mining and Restoration in Alpine Areas: A Case Study of the Muli Coalfield on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 162919–162934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Guo, J.; He, T.; Lei, K.; Deng, X. Assessing the ecological impacts of opencast coal mining in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau-a case study in Muli coal field, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 153, 110454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Guo, H.; Ouyang, X.; Gunasekera, D.; Sun, Z. Land surface temperature retrieval from SDGSAT-1: Assessment of different retrieval algorithms with different atmospheric reanalysis data. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2492314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Dozier, J. A Generalized Split-window Algorithm for Retrieving Land-surface Temperature from Space. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1996, 34, 892–905. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S.; Shuey, C.; Russ, A.; Fang, H.; Chen, M.; Walthall, C.; Daughtry, C.; Hunt, R. Narrowband to broadband conversions of land surface albedo: II. validation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 84, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valor, E. Mapping Land Surface Emissivity from NDVI: Application to European, African, and South American Areas. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 57, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdun, I.; Bechtold, M.; Sagris, V.; Mander, U. Satellite Determination of Peatland Water Table Temporal Dynamics by Localizing Representative Pixels of A SWIR-Based Moisture Index. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, C. Geodetector: Principle and prospective. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 116–134. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Qi, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Yang, R.; Cao, Y. Variation of land surface temperature and its influencing factors in Muli Coalfield, Qinghai Province. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2023, 45, 980–992. [Google Scholar]

- Firozjaei, M.; Sedighi, A.; Firozjaei, H.; Kiavarz, M.; Panah, S. A historical and future impact assessment of mining activities on surface biophysical characteristics change: A remote sensing-based approach. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 122, 107264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owolabi, A.; Amujo, K.; Olorunfemi, I. Spatiotemporal changes on land surface temperature, land and water resources of host communities due to artisanal mining. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 36375–36398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Chatterjee, R.; Kumar, D.; Panigrahi, D. Spatio-temporal variation and propagation direction of coal fire in Jharia Coalfield, India by satellite-based multi-temporal night-time land surface temperature imaging. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2021, 31, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, H.; Xu, F. Spatiotemporal changes in desertified land in rare earth mining areas under different disturbance conditions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 30323–30334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Ruan, M. Research on Temporal and Spatial Resolution and the Driving Forces of Ecological Environment Quality in Coal Mining Areas Considering Topographic Correction. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Deng, Y.; Wang, J.; Luo, M. Fine identification of vegetation types in open pit mining regions using combined UAV RGB imagery and LiDAR point cloud data. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2515269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).