Abstract

Although interest in tidal energy has increased in recent years, its development remains significantly behind that of other renewable sources such as solar and wind energy. This delay is primarily caused by the complex and harsh ocean environment, which imposes significant constraints on operational systems. This paper proposes a new approach to the design and control of a marine current turbine (MCT) emulator without a pitch mechanism, operating in real time below the rated marine current speed.The emulator control strategy integrates two approaches: predictive control for regulating the speed of the DC machine, and a Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) control scheme for maximizing power extraction from the marine current. Our experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed hybrid control strategy, which allows precise tracking of reference signals and stable regulation of the direct current machine (DCM) speed, thereby ensuring synchronization with the turbine’s rotational speed. This approach ensures optimal and robust performance over the entire range of marine current variations.

Keywords:

marine current; model predictive control; LQR; MPPT; converters; emulator; energy converter systems 1. Introduction

In light of the escalating climate emergency driven by greenhouse gas emissions resulting from the extensive consumption of fossil fuels, the deployment of low-carbon renewable energy sources represents a promising alternative [1]. Since the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, followed by the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 and the Paris Agreement in 2015, international political commitments have been established to reduce reliance on fossil fuels in favor of low-carbon energy solutions.

Covering approximately 70% of the Earth’s surface, seas and oceans constitute a vast and largely untapped source of clean and renewable energy for electricity generation. Marine renewable energy (MRE), which encompasses energy derived from waves, offshore wind, marine currents, tides, and thermal and salinity gradients, offers a diverse portfolio of renewable resources. According to [2], most offshore renewable energy technologies remain at the research and experimental stages. Tidal energy systems, particularly those based on horizontal-axis turbines, are among the most mature technologies and are approaching commercialization; however, their large-scale deployment continues to face substantial economic and technical challenges [3]. In contrast, emerging technologies such as Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC) and salinity gradient energy are still in early experimental phases, with ongoing research primarily focused on enhancing their thermodynamic efficiency and economic feasibility [4,5].

Tidal energy is among the most promising marine renewable energy resources. With an estimated global potential of approximately 100 GW [6,7], it represents a significant and non-negligible source of clean energy. Although tidal turbines operate according to principles similar to those of wind turbines—enabling the adaptation of well-established variable-speed control technologies—tidal energy conversion systems can be considerably more compact for an equivalent power output. This advantage arises primarily from the much higher density of water, which is approximately one thousand times greater than that of air, as illustrated in Table 1 [8].

Table 1.

Comparison of a turbine with the same dimensions in air and water.

Fully submerged tidal turbines offer the advantage of minimal visual impact. However, their deployment requires site-specific anchoring systems, regular maintenance, and specialized infrastructure for power transmission and operational management [9]. A key advantage of tidal energy conversion lies in its high degree of predictability. The cyclical nature of tides, combined with the gradual variation in current velocities, results in a stable and foreseeable power output. Consequently, tidal power can be more readily integrated into electrical grids than intermittent renewable energy sources such as wind and solar energy [10,11].

Based on the previously presented maturity curve for marine energy technologies, it can be observed that most tidal turbine systems currently under testing are not connected to the electricity grid or to onshore loads. For the limited number of technologies that are grid-connected, the control and piloting strategies—when implemented—are generally not disclosed due to confidentiality constraints. Consequently, most existing projects remain focused on hydrodynamic testing, turbine efficiency optimization, and the design of generators specifically adapted to the marine environment.

As with wind energy systems, the overall efficiency of a grid-connected tidal turbine depends strongly on the selected system configuration or topology, the type of power electronic converters, and their associated control strategies. It is therefore essential to assess the impact of varying operating conditions on the entire power conversion chain in order to optimize the performance of each subsystem across all operating regimes. Furthermore, the design of an efficient control strategy is crucial to maximize energy extraction from the tidal turbine. For grid-connected applications, this extracted energy must also be injected into the grid with high power quality. This capability is largely enabled by the high degree of control flexibility offered by dual-stage power conversion architectures in grid-connected tidal turbine systems.

To meet their power production targets, tidal turbine systems must achieve a high level of reliability in order to minimize maintenance interventions at sites that are difficult to access. One effective approach is to adopt simple and robust technologies that enhance the reliability of individual system components. This consideration often leads to minimizing the use of mechanical elements. For example, eliminating the mechanical gearbox significantly reduces maintenance requirements. In such configurations, direct-drive systems employing low-speed, high-torque generators, such as permanent magnet synchronous generators (PMSGs) using high-energy rare-earth magnets, are required. Several industrial developers, including OpenHydro and Clean Current, have successfully implemented direct-drive tidal turbine concepts based on this type of generator [12,13,14].

However, fixed-speed tidal turbines exhibit several drawbacks, including low energy efficiency, since they are optimized for a single operating point, and reduced lifespan due to the high mechanical stresses imposed on their structure [15,16]. Variable-speed tidal turbines were therefore introduced to address these limitations [17,18]. By allowing variable rotational speeds, power fluctuations can be effectively attenuated. As a result, the annual energy production of variable-speed tidal turbines can be increased by 10% to 35% compared with fixed-speed systems [19]. Furthermore, numerous studies have demonstrated that control strategies have a significant impact on both turbine loading and the performance of the electrical system [20]. Regardless of the tidal turbine configuration, the control strategy remains a key determinant of overall system performance. The objectives of the control law for a variable-speed tidal turbine are generally defined by the following three main points [21,22,23]:

- Maximization of power generation below the rated power, ensuring that the tidal turbine operates at maximum efficiency under low marine current speeds.

- Maintenance of acceptable power quality around the nominal power under intermediate marine current speeds.

- Minimization of mechanical stress on the rotor, blades, and drivetrain.

This paper focuses on the design, modeling, and control of a 3 kW variable-speed tidal turbine implemented on a dSPACE 1104 real-time control platform. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the state of the art in predictive control techniques. Section 3 presents the mathematical formulation of the predictive control model. Section 4 describes the modeling of the tidal energy conversion chain. In Section 5, the application of Model Predictive Control (MPC) to the simulation of a marine current turbine system is presented. Section 6 details the real-time implementation and experimental validation of the MPC strategy on the dSPACE 1104 platform. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2. Related Work

This section reviews and discusses the existing literature related to Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) control and Model Predictive Control (MPC) approaches. Relevant references addressing the theoretical foundations, design methodologies, and practical applications of LQR controllers are first examined. Subsequently, studies focusing on MPC controllers, including their variants and implementations in power electronic systems, are analyzed. Through this discussion, the strengths, and limitations aspects of LQR- and MPC-based control strategies reported in the literature are highlighted.

Recently, many controllers based on nonlinear control have been used to model wind turbines. Boukhezzar and Siguerdidjane [24,25] used a non linear controller to deal with the wind power capture op timization problem while restricting transient loads on the drivetrain components. Prasad et al. [26] developed a new control approach for the generations and loads in the integrated wind power system. This control approach is based on nonlinear control. Finally, optimal control has been widely used to model and design the variable-speed wind turbine. Optimal con trol can be applied in two quadratic linear forms, namely, linear quadratic regulator (LQR) and linear quadratic Gaussian (LQG).

Barrera-Cardenas and Molinas [27] applied the LQG control to model wind turbines. The proposed LQG control has shown useful properties, good performance, and robustness in controller design which has been applied to wind energy converter systems. Kumar and Stol [28] proposed and tested the use of Simulink to simulate the LQR controller for wind turbines to achieve better rotor speed regulation. To maximize the energy generated from wind, in the reference [29], Fakharzadeh et al. presented a linear control law using the LQR approach. Bayat and Bahmani [30] addressed both the problems of power regulation and wind turbine control using the LQR approach feedback. Mahmoud and Oyedeji [31] proposed a new voltage control scheme based on the LQR control design for a grid-connected wind farm. The proposed solution can be conveniently utilized for multi-input multi-output systems.

Soliman et al. [32] pioneered high-performance control by utilizing the Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) to drive frequency converters, demonstrating superior DC-link stability compared to conventional methodologies. In parallel, to optimize the dynamics of Doubly Fed Induction Generators (DFIG), Zgarni and El Amraoui [33] introduced the LQR-GA approach, which employs Genetic Algorithms for automated gain tuning. They further proposed a Robust LQMinMax variant designed to ensure stability in the presence of parametric uncertainties and worst-case disturbance scenarios. These control strategies have evolved beyond internal power regulation to provide grid-support services. To this end, Gil-González et al. [34] developed an adaptive virtual inertia method based on an LQR-driven synchronverter model, enabling wind turbines to actively compensate for grid frequency fluctuations. Finally, research by Boukili and Aguiar [35] corroborates this trend by exploring advanced LQR strategies to enhance the global robustness of DFIGs, thereby consolidating the LQR framework as a cornerstone of future intelligent wind turbine control.

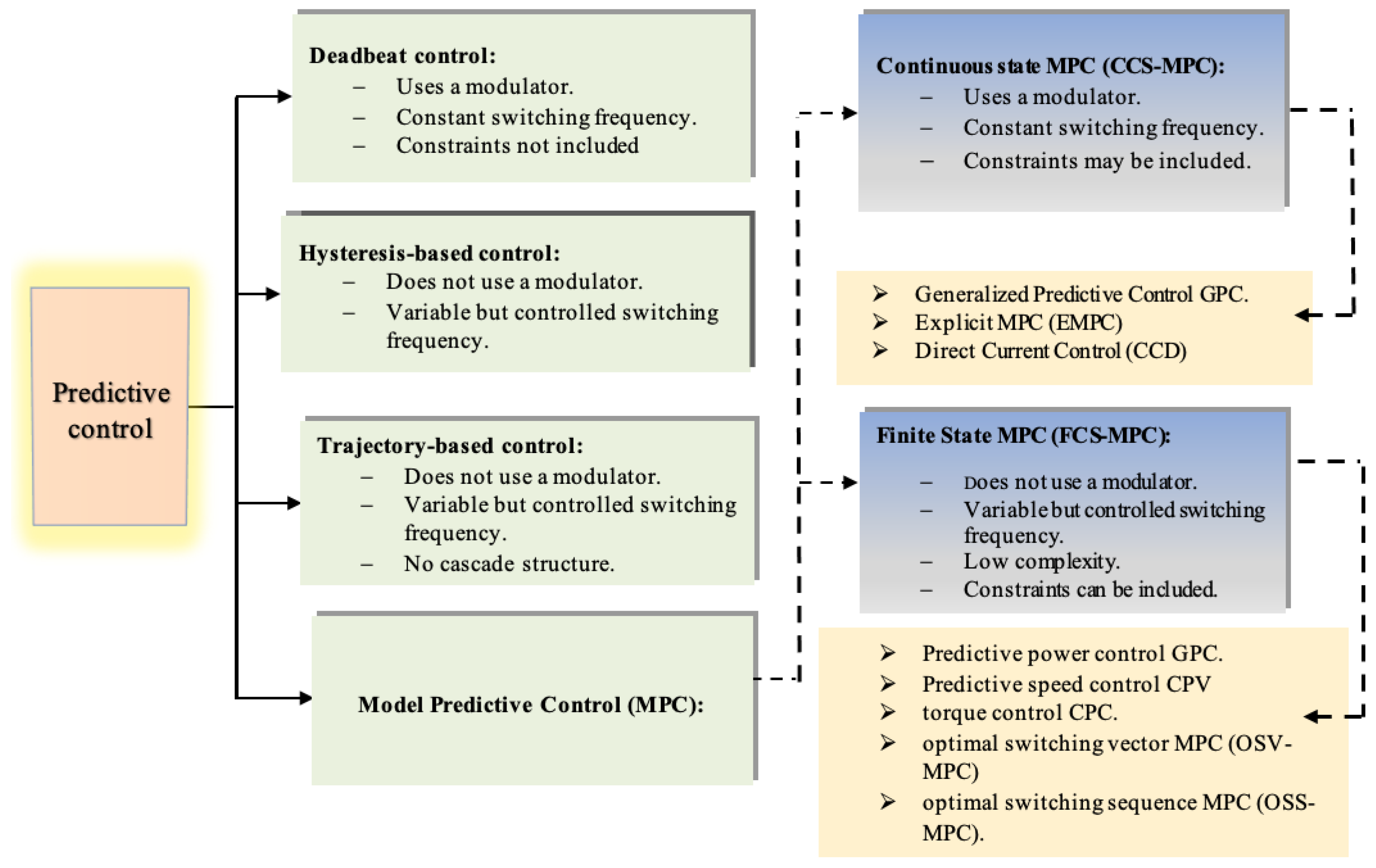

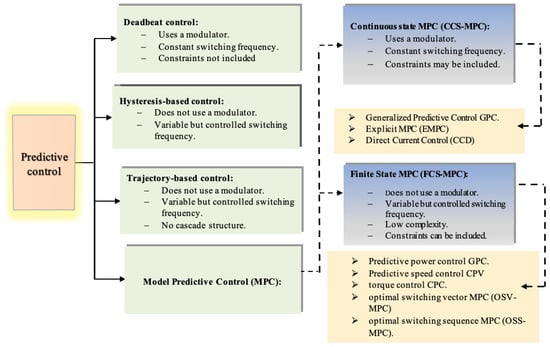

On the other hand, predictive control includes a wide range of strategies for controlling power converters [36]. These strategies typically rely on simplified mathematical models of the converters to predict the evolution of the state variables at each sampling instant [37]. In this context, Figure 1, provides an overview of the main predictive control techniques for power converters, which can be classified into four categories: deadbeat control [38,39], hysteresis-based predictive control [40], trajectory-based predictive control [41], and model predictive control (MPC) [42].

Figure 1.

Classification of control strategies based on predictive control.

Predictive control based on model predictive control (MPC) offers several advantages that make it well suited for power converter control. It can be applied to a wide range of processes, is suitable for multivariable systems, and allows compensation for delays. Moreover, system constraints and nonlinearities can be incorporated into a single control law [43]. Predictive control strategies share a common principle: they rely on a mathematical model of the system to predict future behavior and to determine the appropriate control action.

Several predictive control methods for power converters have been proposed in the literature. According to [44,45,46], the model predictive control (MPC) applied to power converters can be classified into two main categories: continuous-state MPC and finite-state MPC. In the first category (continuous-control-set MPC), a Pulse Width Modulator (PWM) or Space Vector Pulse Width Modulator (SVPWM) is required to apply the control signal, as the predictive control output is continuous [47]. In contrast, the second type of control leverages the discrete nature of power converters to solve the optimization problem. In this approach, a limited number of switching states are considered, and a discrete model is used to predict the future operation of the system for each admissible control sequence. The switching action that minimizes a predefined cost function is selected and applied; consequently, a modulator is not required [48].

In this paper, a continuous model of the converter is assumed, meaning that the switching states of the semiconductors are not explicitly considered within the control algorithm. Consequently, a continuous control signal is generated. To produce the switching pulses, a modulator (PWM or SVPWM) is then employed at the controller output [49]. Accordingly, this approach is known as Continuous Control Set Model Predictive Control (CCS-MPC). Although the control design is widely used in wind turbine technology, to the best of our knowledge, only a few studies considered the control of MCTs. Zhou et al. [50] proposed two control strategies (i.e., speed con trol and torque control) for the power limitation of the MCT when the speed of the marine current exceeds the nominal value. The torque control strategy limits the generator power to a certain value during the dynamic process. However, the proposed control strategy limits only the power for the high-speed marine current. It does not deal with the entire range of variations of the marine current speed. Toumi et al. [51] reported on speed control using only the classical proportional integral correctors. The design of this type of control is robust in the case where the MCT is coupled with the permanent magnet synchronous generator. Nevertheless, this type of control cannot maximize the energy efficien cy of the MCT. To cope with these drawbacks, in our previous study [52], we have proposed an efficient LQR design for maximizing the power efficiency and energy capture of the MCT. However, the major limitation of this contribution lies in the absence of real experimental validation to verify the reliability of this controller in the context of wind turbine technology. The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- We have used a profile of the daily variation of marine current speed in the northern coasts of Morocco;

- We have developed a hybrid control scheme based on LQR and MPC approaches that optimizes the performance of the marine current turbine emulator;

- We successfully obtained experimental results for the assembled system through implementation on a dSPACE 1104 controller.

3. Mathematical Modeling of Controllers

This section presents the detailed mathematical formulation for two control frameworks: Model Predictive Control (MPC) and the Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR).

3.1. Mathematical Modeling of Model Predictive Control (MPC)

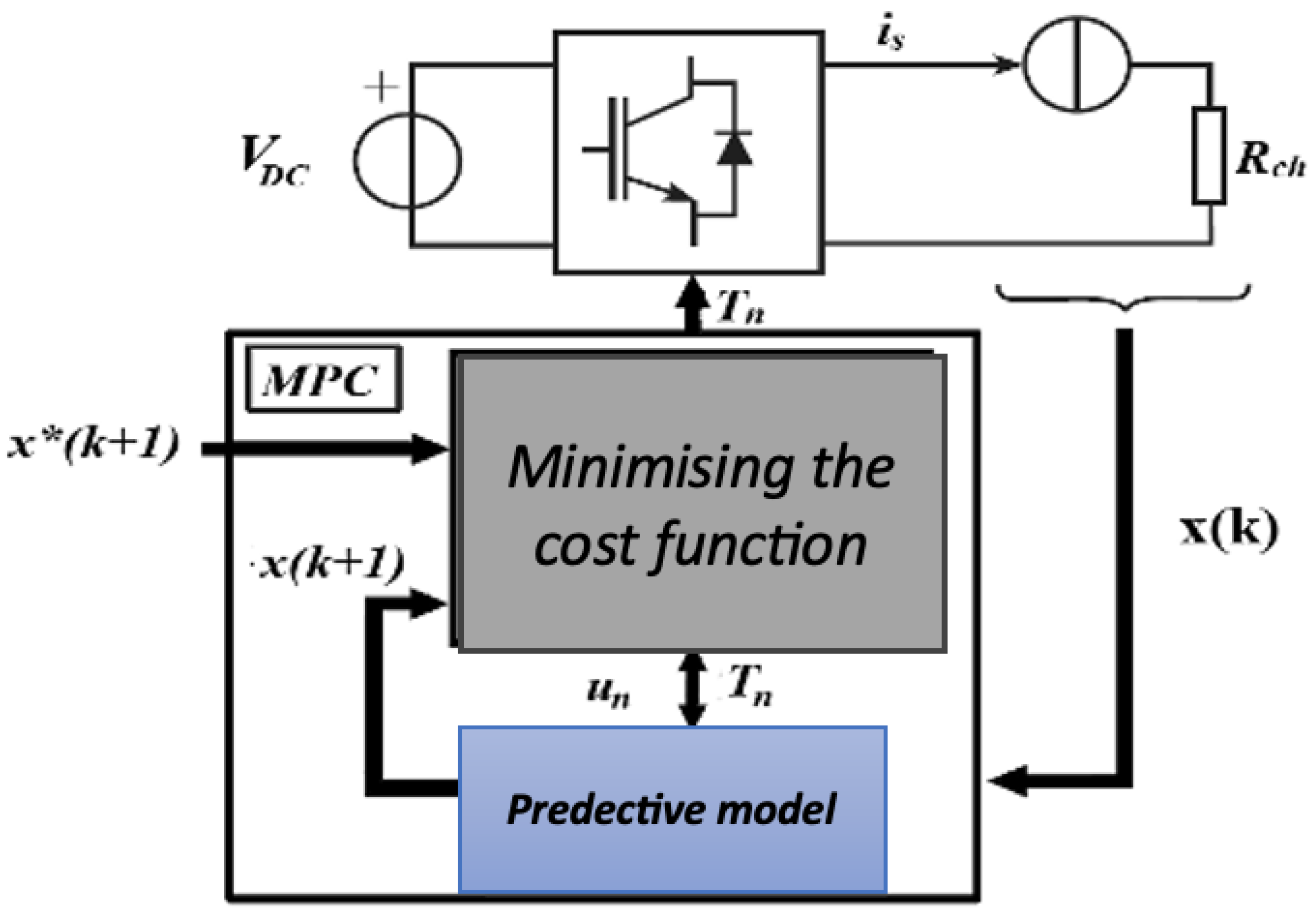

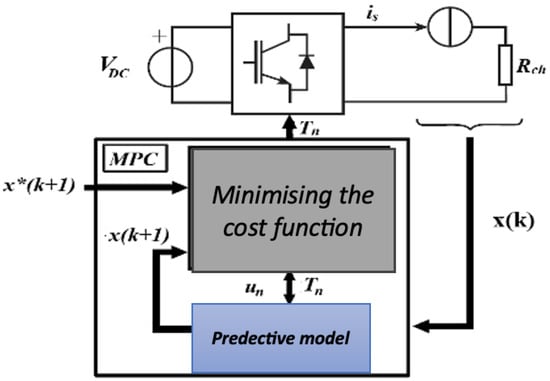

Model Predictive Control (MPC) is an advanced process control technique that employs a mathematical model to predict the future behavior of a system and optimize its control inputs. Figure 2 illustrates the MPC strategy implemented for the power converter, and a detailed formulation of the continuous-state MPC model is presented below:

Figure 2.

The MPC strategy for a power converter.

- Continuous-State Model Predictive Control

Consider a continuous-time system described by a set of differential equations

where:

- is the state vector at time t.

- is the control input vector at time t.

- represents the system dynamics.

For simplicity, we often use a linear approximation of the system dynamics:

where A and B are matrices of appropriate dimensions.

- Discretization

For MPC, we need a discrete-time model. Discretize the continuous-time system using a sampling period :

- is the state victor at the kth sampling instant.

- is the control input vector at the kth sampling instant.

- and .

- Prediction Model

The prediction model over a prediction horizon N step is given by:

where:

- A and B are block matrices of constructed from and .

- Cost Function

The MPC controller aims to minimize a cost function over the prediction horizon. A common choice for the cost function is a quadratic function:

- is the reference state.

- Q and R are positive definite weighting matrices.

In matrix form, the cost function can be written as:

- Constraints

MPC can handle constraints on states and inputs:

In matrix from these constraints are:

- Optimization Problem

The MPC problem at each time step k is to solve the following quadratic programming (QP) problem:

subject to:

- Control Law

The optimal control sequence U is computed by solving the QP problem. The first control input from this sequence is applied to the system. The process is repeated at each sampling instant, using the updated state measurement. This mathematical framework allows MPC to handle multivariable control problems with constraints, providing a powerful and flexible control strategy for continuous-state systems.

3.2. Strategy of the Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR)

Linear quadratic Regulator (LQR) is a synthesis method used to determine the optimal control of a system that minimizes a quadratic performance criterion [53,54]. This criterion is quadratic in both the system states and the control inputs. The design process involves carefully selecting the weighting matrices in the cost function to achieve the desired closed-loop system behavior. Once these matrices are defined, the optimal gains are obtained by solving an algebraic Riccati equation. One of the main advantages of LQR control is its inherent robustness properties. However, such stability is guaranteed only under ideal conditions: when the model is perfectly known, the full system state is available, and the signals are free from noise. This control strategy has been successfully implemented on experimental platforms such as helicopters [55] and coaxial rotor UAVs [56]. A comparison between the PID and LQR approaches is provided in [57,58]. Overall, the LQR approach demonstrates superior performance not only in trajectory tracking but also in terms of energy efficiency [59].

3.3. Mathematical Modeling of LQR Control

The principle and model of optimal system control can be represented by the following state-space equation:

where:

- indicates the state vector,

- is the output vector,

- is the output vector,

- A is the state matrix,

- B is the control matrix,

- C is the output matrix, containing the measured values.

By writing , the Hamiltonian system is written as follows:

The Hamiltonian system must satisfy the following conditions

The equation of state:

The absence of constraints on the regulator:

From Equation (12), we derive the following expression:

Then, the dynamic equation of the closed-loop system can be written as follows:

Both Equations (11) and (12) can be expressed as a matrix system called the Hamiltonian system:

On the one hand, Equation (11) can be rewritten as follows:

On the other hand, Equation (14) can be rewritten as follows:

Then, the cost criterion of the initial state ( at ): is written as follows:

The optimal control obtained is identical to a state feedback given by: with: .

4. Modeling the Conversion Chain for Tidal Energy

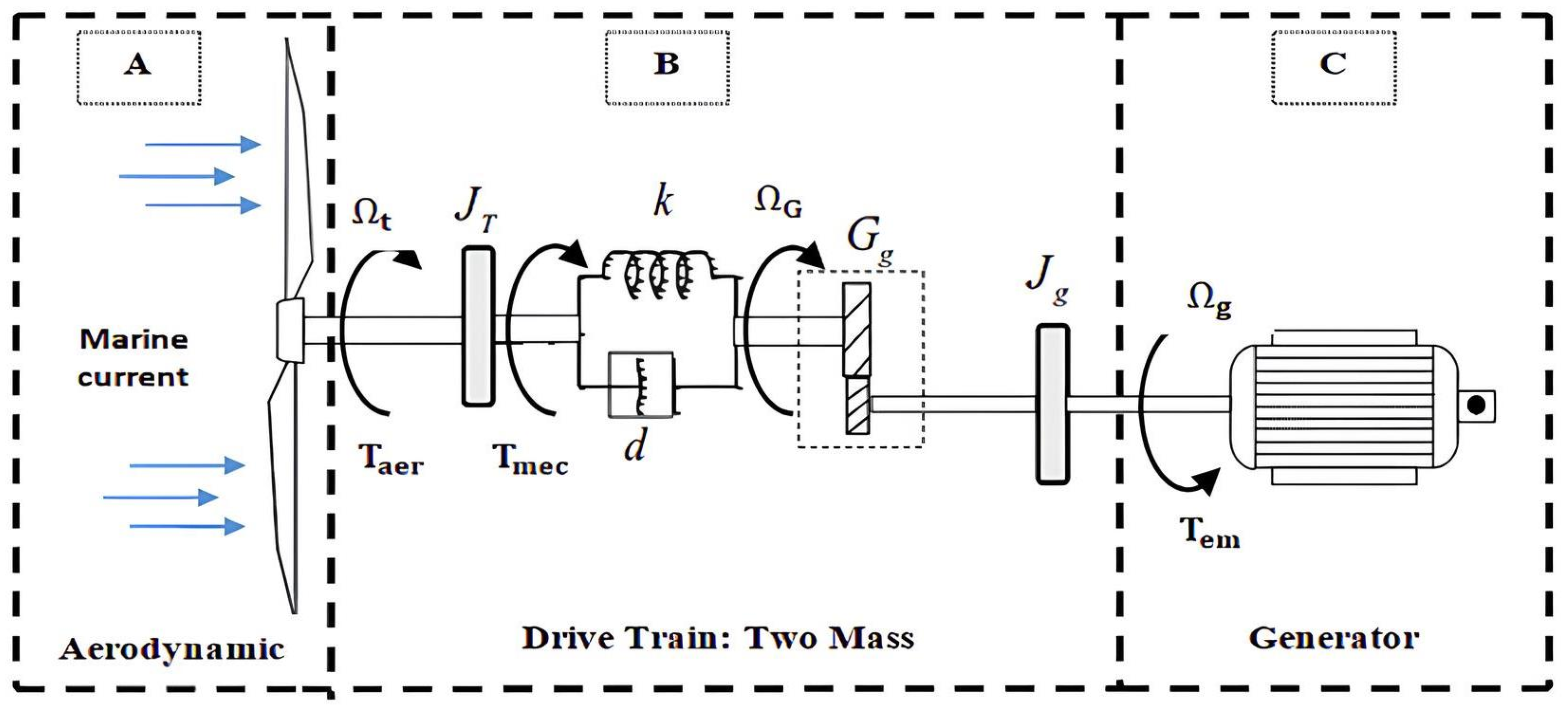

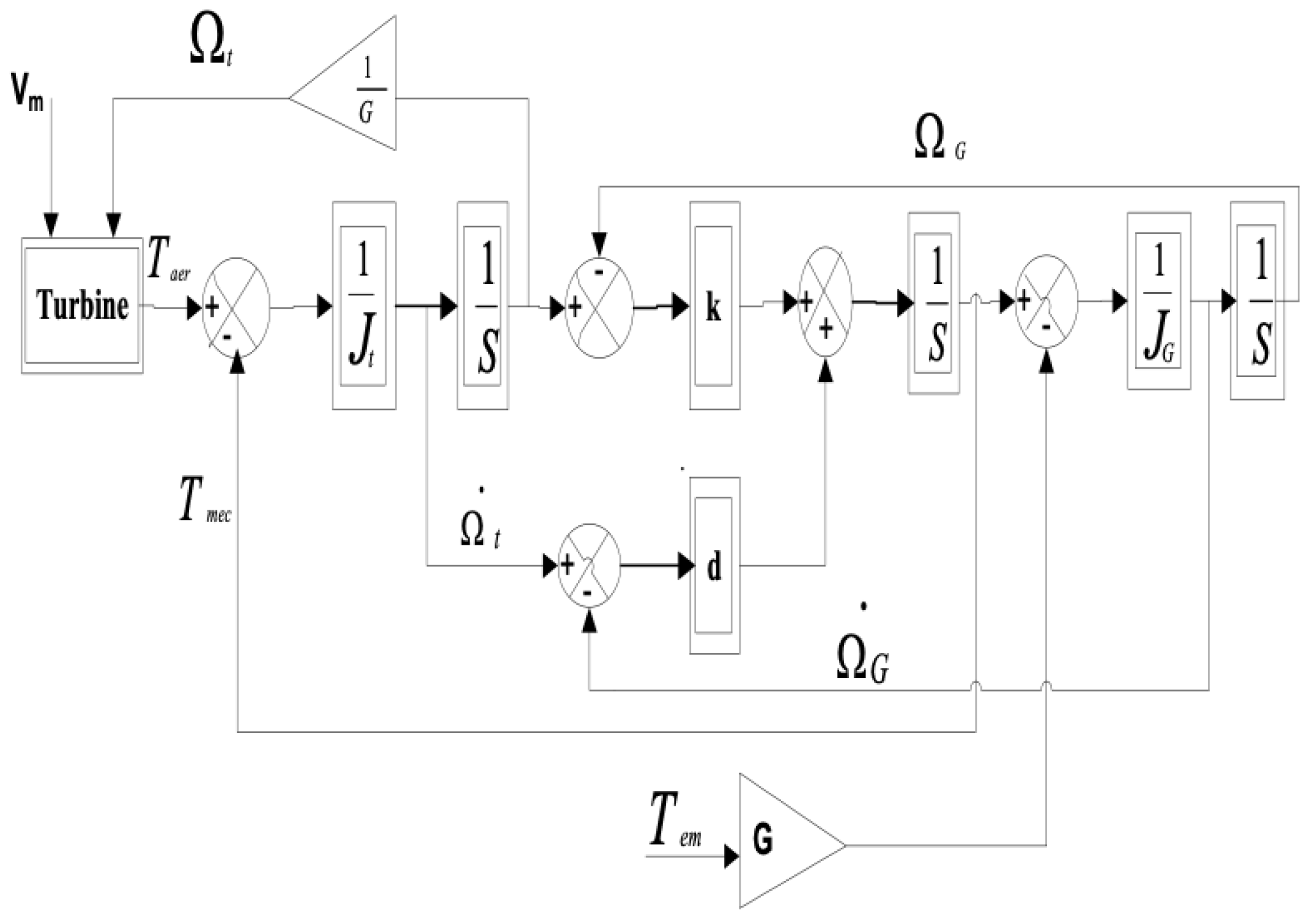

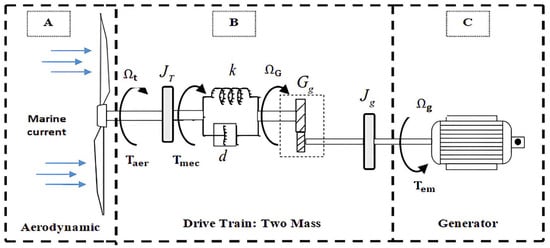

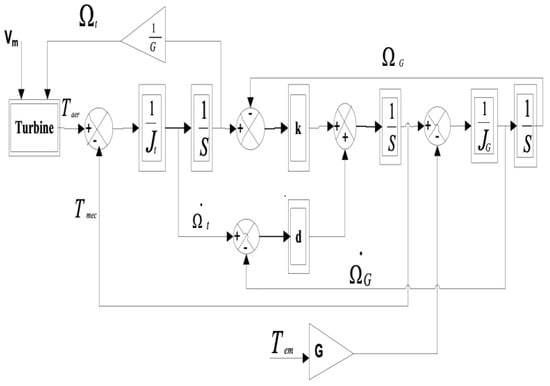

As illustrated in Figure 3, the marine current energy conversion chain consists of three subsystems, which are described in detail below.

Figure 3.

MCT model [52].

- 1.

- The aerodynamic subsystem (Figure 3A): Driven by the hydrodynamic energy of tidal currents, the tidal turbine is mechanically coupled to the generator rotor and converts this energy into mechanical rotation, which is subsequently transformed into electrical energy through a process similar to that of wind turbines. Unlike wind turbines, the blade pitch angle of tidal turbines is generally fixed due to the predictable and stable direction of tidal currents. In this study, a three-bladed horizontal-axis turbine is considered, with a blade profile inspired by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) airfoil family [60,61]. Based on Blade Element Momentum (BEM) theory, this airfoil is widely recognized as effective for the hydrodynamic characterization of turbine performance.

- 2.

- The mechanical subsystem (Figure 3B) consists of the gearbox and the transmission shafts. The gearbox adapts the rotational speed of the turbine to that of the generator through two shafts, namely a low-speed shaft on the turbine side and a high-speed shaft on the generator side. Power transmission must account for the total inertia of the blade–hub–shaft–generator rotor assembly; therefore, accurate modeling of the entire drivetrain is required.

- 3.

- The electrical subsystem consists of the generator and a power electronics module, which convert the mechanical energy extracted from the turbine into electrical energy. The dynamic response of the electrical machine and the associated power electronics is significantly faster than that of the mechanical components. As a result, the dominant system dynamics are governed by the mechanical subsystem, and the tidal turbine system is therefore treated as a mechanical structure. Consequently, the generator is modeled under the assumption that its electromagnetic torque instantaneously follows its reference value [62].

The electrical power is equal to the product of the electromagnetic torque and the speed of rotation of the generator :

In the following sub-sections, the modeling approach for each subsystem is presented.

4.1. Modelling the Source

A site for harnessing energy from marine currents is identified based on a set of selection criteria. These criteria must satisfy constraints related to operating conditions (current speed, spatio-temporal variability, turbulence, swell, bathymetry, etc.), distance from the coast (for electricity transmission), maintenance requirements, and environmental and socio-economic impacts (sediments, flora and fauna, navigation, military zones, fishing activities, etc.). Among these factors, the most critical criterion is the determination of the current speed at the site to be exploited. There are two main approaches for predicting and measuring the speed of marine currents:

- One approach is through modeling, for which several methods exist to represent marine currents, including the Harmonic Analysis Method (MAH), the Double Cosine Method, Tidesim, and Tide 2D [63].

- The second approach is through direct measurement, using conventional devices such as mechanical reel current meters, Doppler profilers, or a practical model proposed by SHOM (Service Hydrographique et Océanographique de la Marine Nationale) [64].

Given the proximity of Ksar Sghir to the Strait of Gibraltar, which is located south of Spain, north of Morocco, east of the Atlantic Ocean, and west of the Mediterranean Sea, data on marine current speeds, frequencies, and directions can be accessed through EMODNET (European Marine Observation and Data Network). EMODNET is a European initiative that collects marine geospatial data from European countries and regional organizations, harmonizes the data using common standards, and provides free public access for consultation.

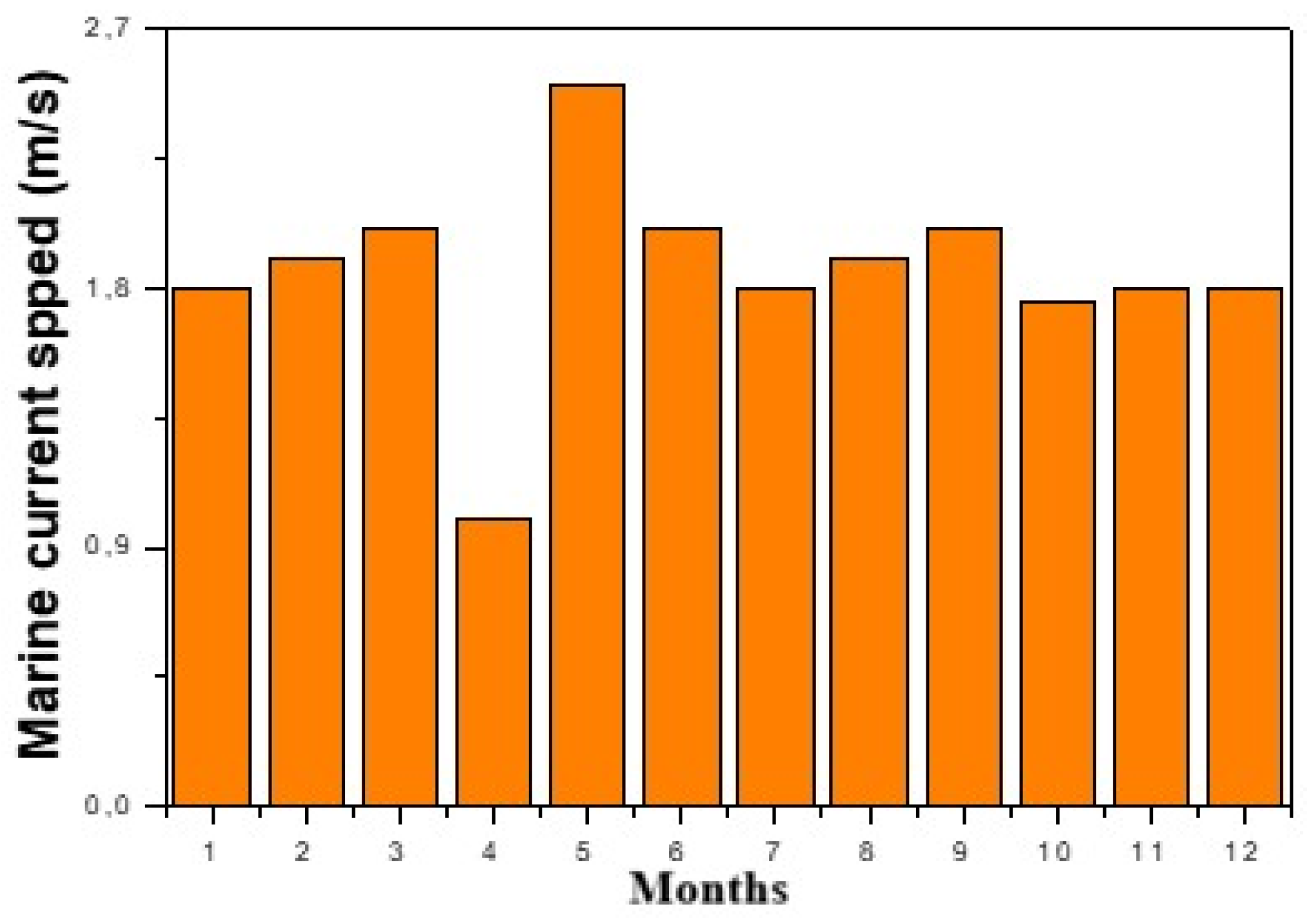

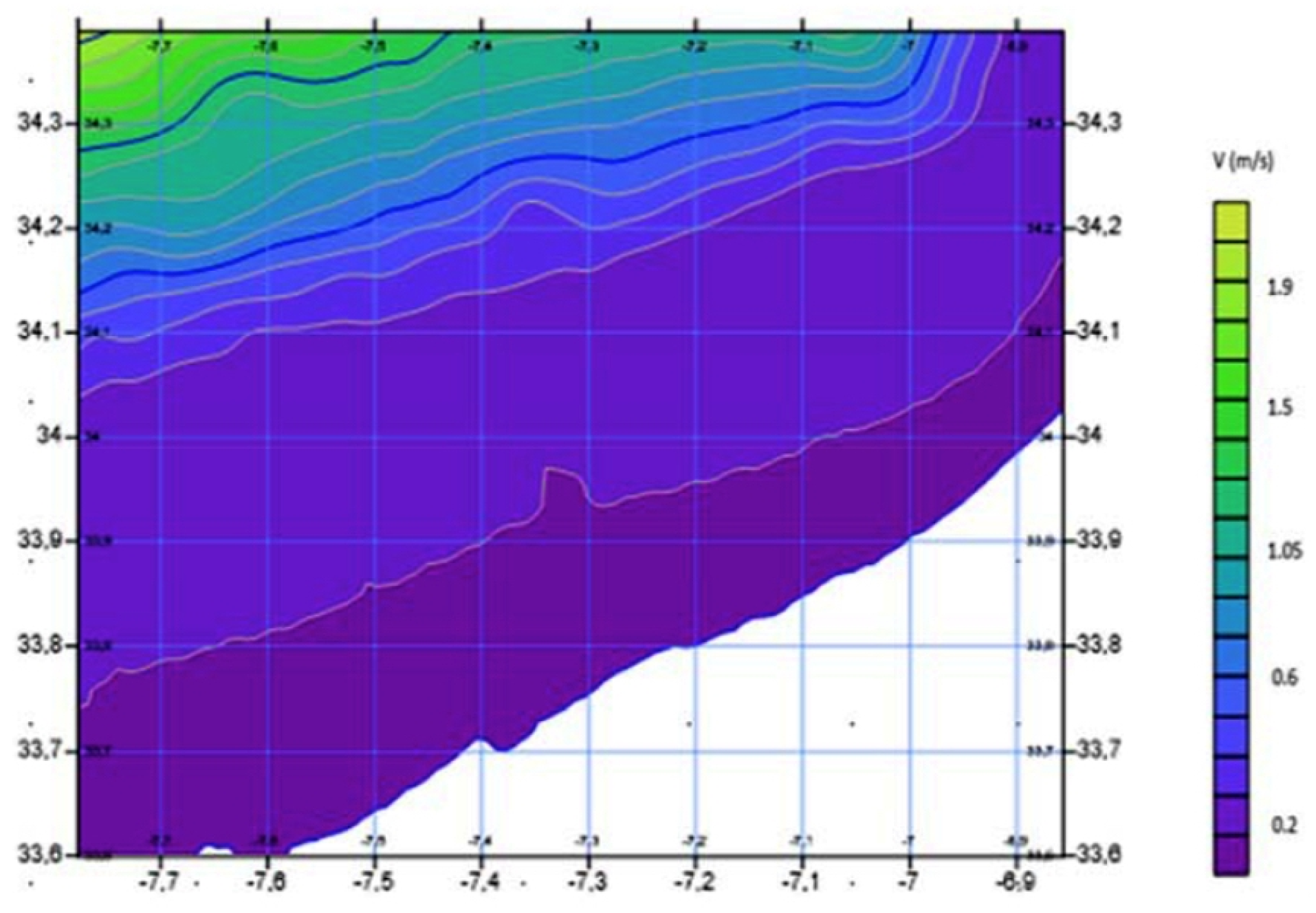

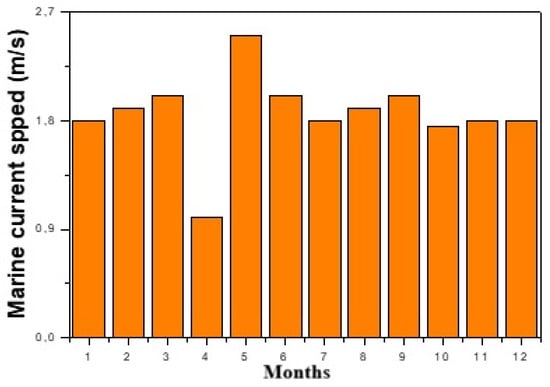

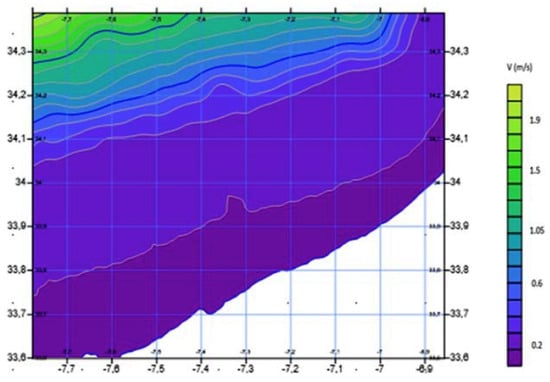

Figure 4 shows the annual profile of marine current velocity at Ksar Srir. The marine current velocity has a maximum value of 2.76 m/s (May), while the minimum marine current velocity of 1 m/s is recorded in April. Another study conducted by Mohammed V University in collaboration with IRESEN [65] reports that the marine current speed at the Tangier site varies between 0.2 m/s and 1.9 m/s, as illustrated in Figure 5. The area closest to the coast has a marine velocity ranging between 0.2 and 0.5 m/s, however, the further out to sea, especially in the water of the pendulum (450 m), the higher the current velocity, ranging between 1.5 and 1.9 m/s.

Figure 4.

Monthly variation in tidal current speed.

Figure 5.

Velocity distribution in (m/s) on the Tangier coast.

4.2. Aerodynamic Modelling and Operation of the Hydroline Turbine

4.2.1. Turbine Aerodynamic Modelling

As with any moving fluid, the kinetic energy contained in a mass of water m, moving at speed v, is defined by the formula:

If this energy could be completely recovered using a tidal turbine, located perpendicular to the direction of the marine current, the instantaneous tidal power would be:

where:

- : the area swept by the turbine blades.

- : the density of the water (approximately 1024 Kg/m3 for seawater).

- : the marine current speed (m/s).

In practice, the tidal turbine can recover only a portion of the kinetic energy from the marine current, as defined by a power coefficient . The aerodynamic power will then have the following expression:

where:

- : Aerodynamic power of the water turbine [W],

- : Power coefficient representing the wind energy conversion efficiency.

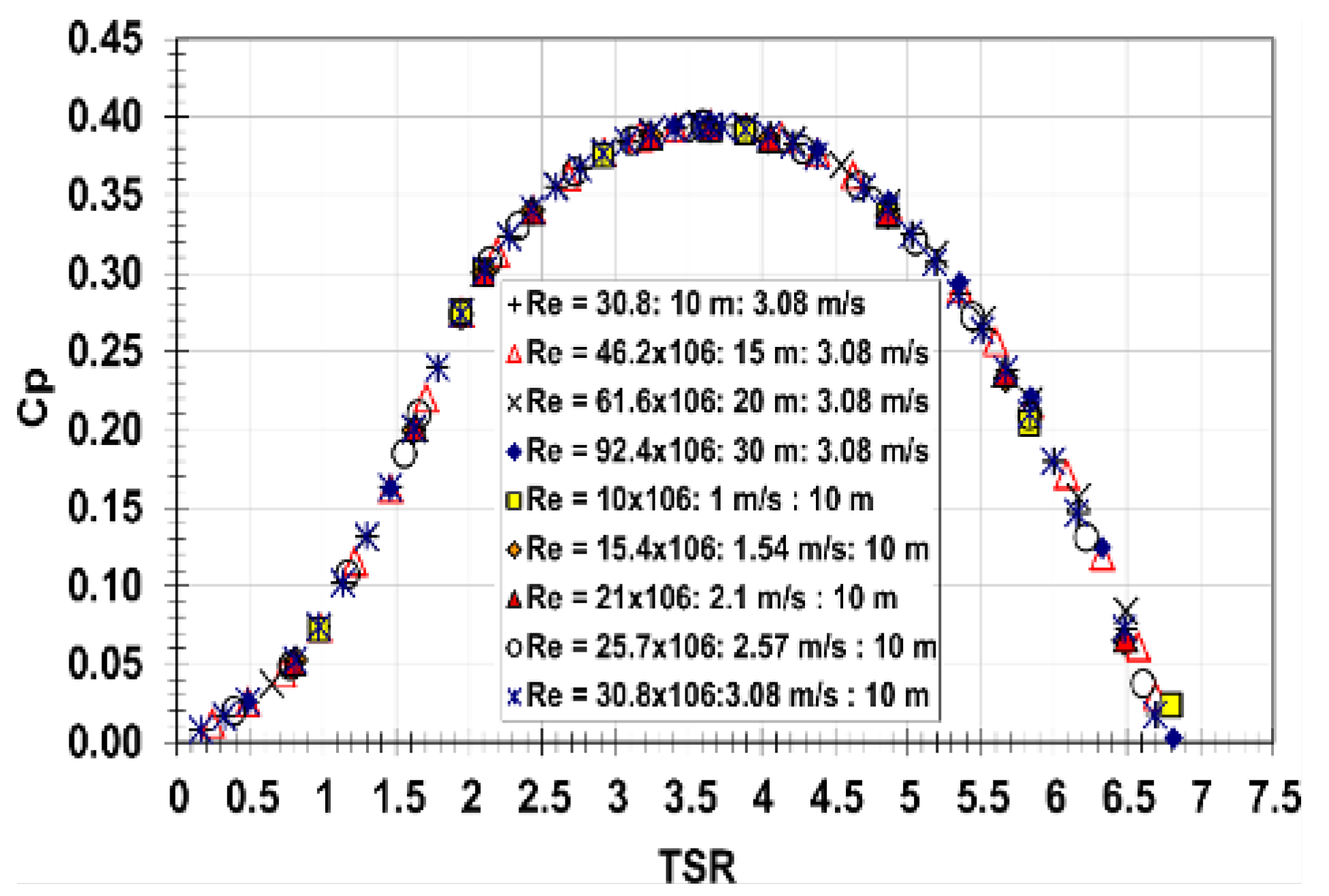

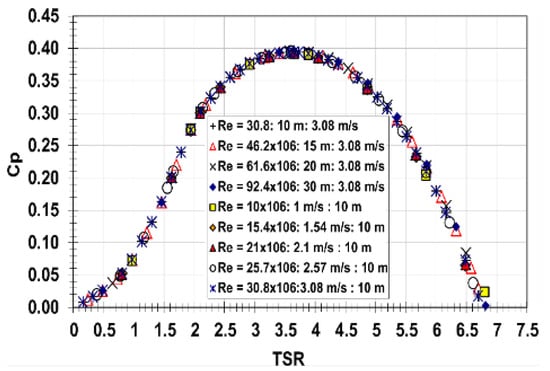

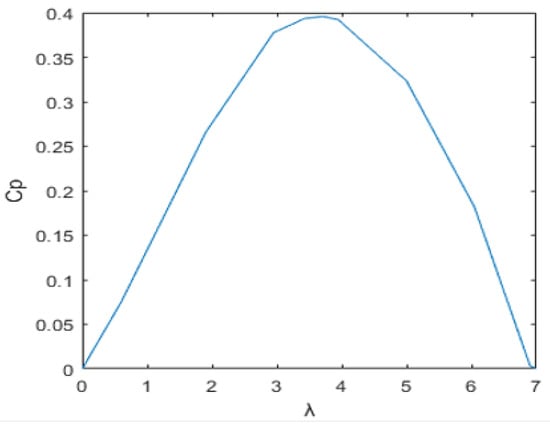

For simulation purposes, we extrapolated from the experimental curves of [66], in the form of a polynomial approximation that provided the best results, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Power extraction coefficient, experimental curves.

The extrapolated model is defined by the equation below.

: the specific speed given by the following expression:

Figure 7 shows the curve of the extrapolated power coefficient as a function of from Figure 6. It is clear that the maximum power coefficient, , is 0.39, occurring at an optimum tip-speed ratio of . At this value, the tidal turbine system will deliver optimum electrical power.

Figure 7.

Power extraction coefficient extrapolated model [52].

Based on the expression () for the power produced by the turbine and knowing the angular velocity of rotation of the latter, the aerodynamic torque of the turbine is expressed as follows:

4.2.2. Operation of the Water Turbine

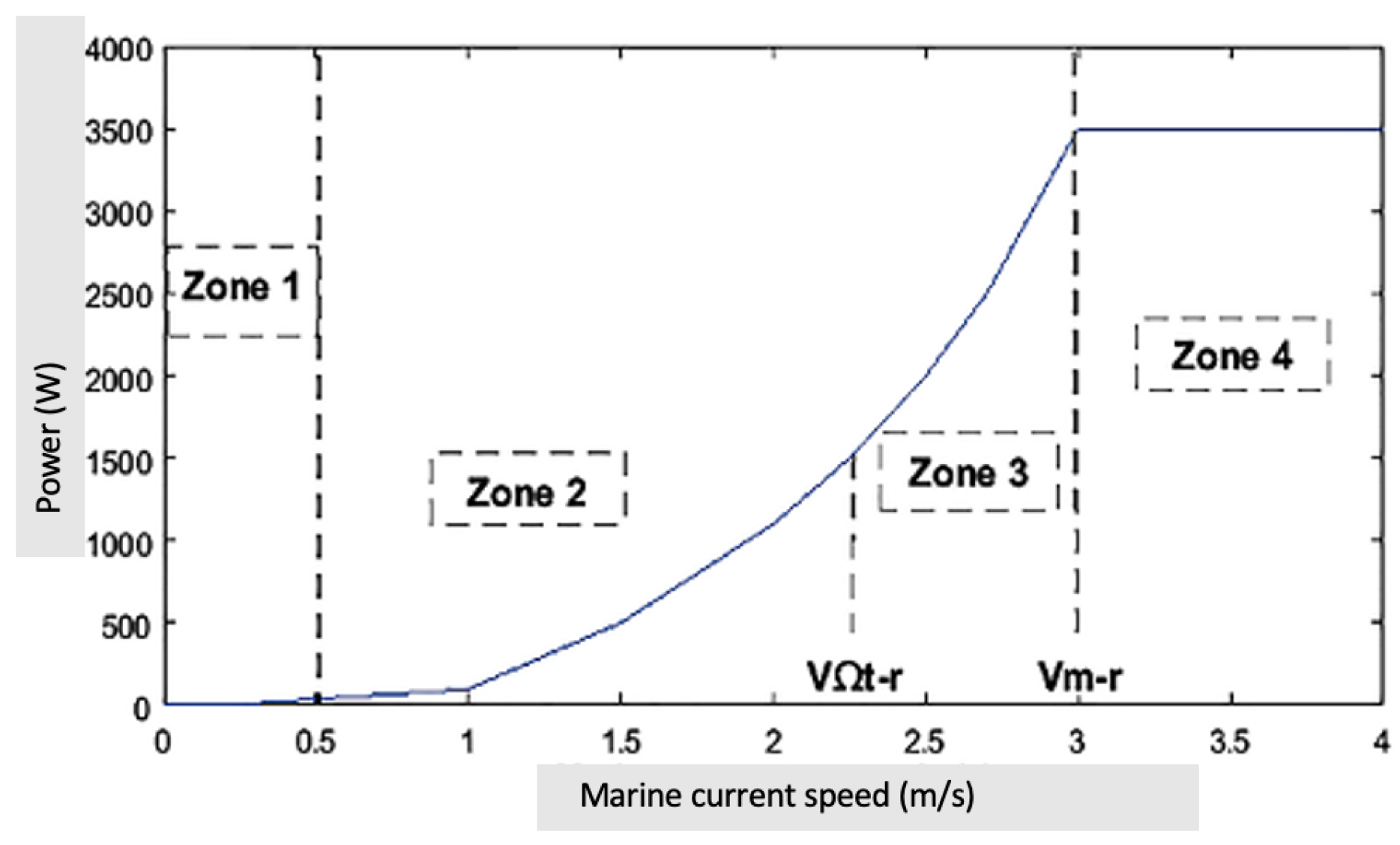

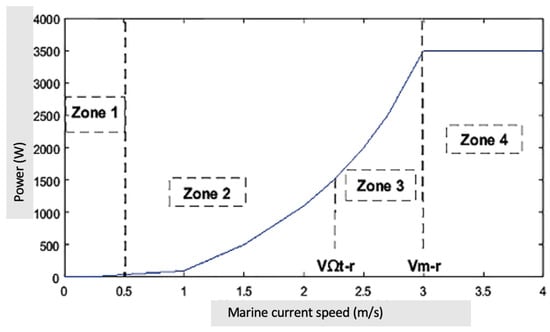

The operation of a variable-speed wind turbine is defined in four operating zones, which are depicted in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Operating zones of a variable speed tidal turbine [52].

- Zone 1: the turbine supplies no power because the tidal speed is lower than the start-up speed .

- Zone 2: the tidal turbine starts to produce energy from a certain speed of connection of the marine current noted Vm. The tidal turbine then operates at partial load 1, which is relative to low marine current speeds.

- Zone 3: as soon as the marine current reaches the speed , the tidal turbine is said to be in partial load 2, which corresponds to intermediate marine current speeds.

- Zone 4: above a certain nominal starting speed (Figure 9), it would be interesting to clip the power. This clipping is of interest in the sizing of the electric generator, as it would be financially useless to size it for a higher current speed, which is only rarely observed.In addition, it protects the tidal turbine against very high current speeds, which are not common because potentially exploitable sites have a maximum current speed of less than 6 m/s. For a site with a maximum current velocity of 3 m/s, the values of the nominal velocities and start-up velocity are estimated at 2.4 m/s and 0.5 m/s respectively. Clipping is generally achieved by means of a regulation device to protect the tidal turbine by keeping its rotation speed constant.

Figure 9. Control system block diagram of tidal turbine.

Figure 9. Control system block diagram of tidal turbine.

4.2.3. Speed Multiplier Model

The speed multiplier adapts the speed of the turbine to that of the generator via two shafts: the slow shaft on the turbine side and the fast shaft on the generator side. The fundamental equation of dynamics is used to determine the change in mechanical speed from the mechanical torque exerted on the rotor shaft of the wind turbine and the electromagnetic torque :

With:

- : generator rotation speed [rad/s],

- G: gearbox gain,

- : angular speed of rotation of the turbine [rad/s],

- : generator torque [Nm],

- : turbine aerodynamic torque [Nm],

4.2.4. Modeling the Mechanical Shaft

Taking into account the flexibility of the shaft, the mechanical coupling between the turbine and the electrical machine in a flexible transmission is modeled using a two-mass model, as shown in Figure 9. The two masses are connected by a flexible shaft characterized by the stiffness of the blade drive shaft, k, and the damping coefficient of the shaft with respect to the gearbox, d. The equations of motion for the low-speed shaft can then be written as follows:

where:

- and are the inertia and rotational speed of the turbine respectively.

- multiplication gain.

- and are respectively the rotational speed and inertia of the generator brought back to the low-speed shaft, and defined by:

The flexible model is represented in Figure 9.

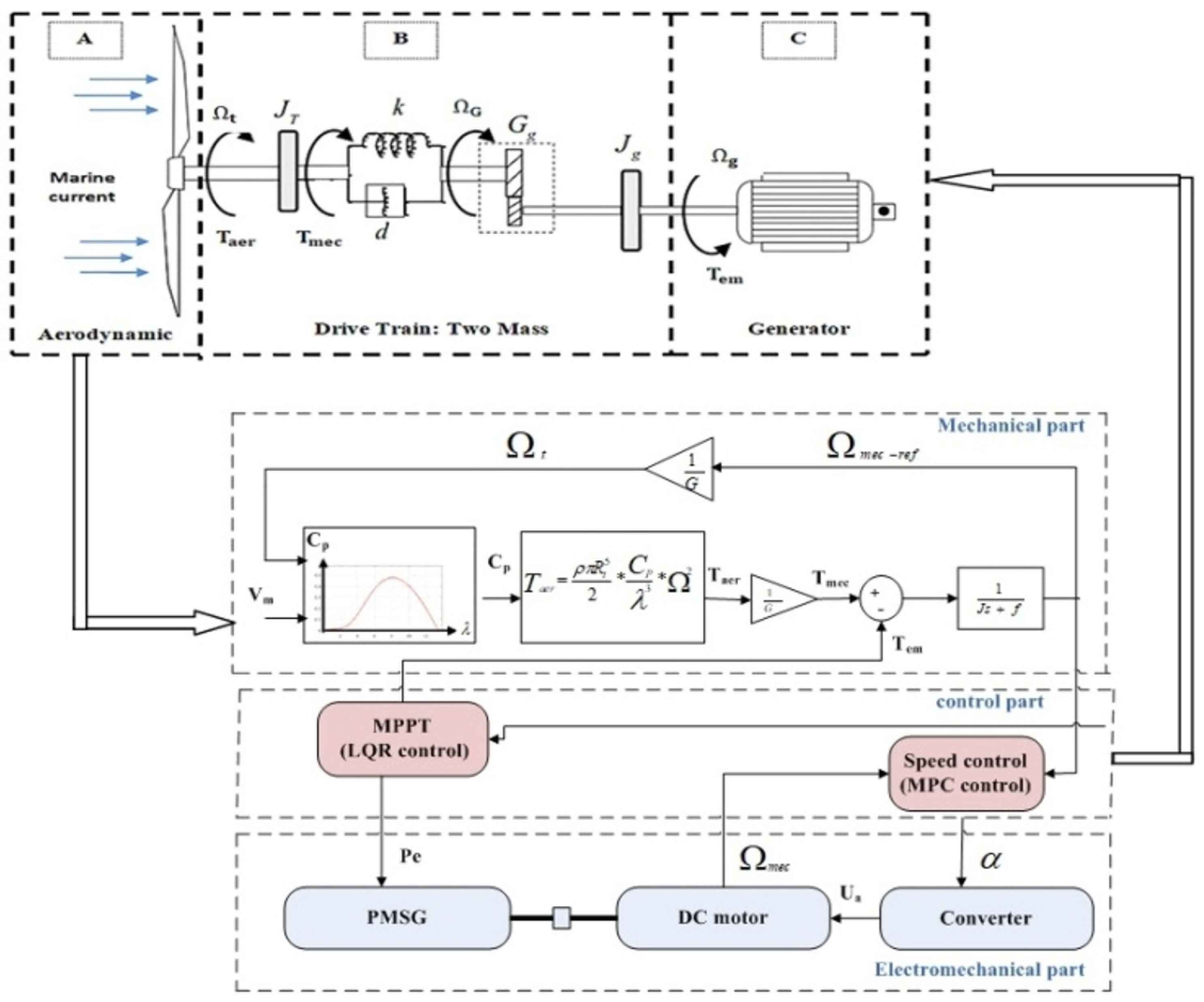

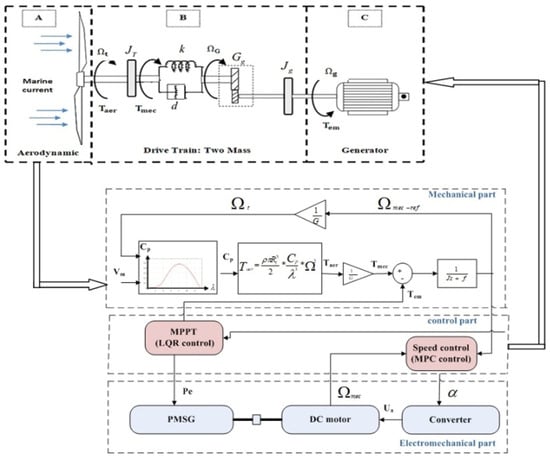

5. Development of a Hybrid LQR-MPC Control for the Tidal Turbine Emulator

Given the complexity of the marine environment and the difficulty of accessing it, we present here a physical emulator of a three-bladed tidal turbine. The purpose of this emulator is to reproduce, in the laboratory, the waveform of the real aerodynamic torque generated by a tidal turbine as accurately as possible, even though the alignment of the blade axis with respect to the marine current and the blade deformation are not considered. Developing such a tool provides significant research cost savings, allows controlled test conditions (simulated marine currents), and enables the integration and efficiency testing of different types of electrical generators within a tidal turbine system and the electrical grid.

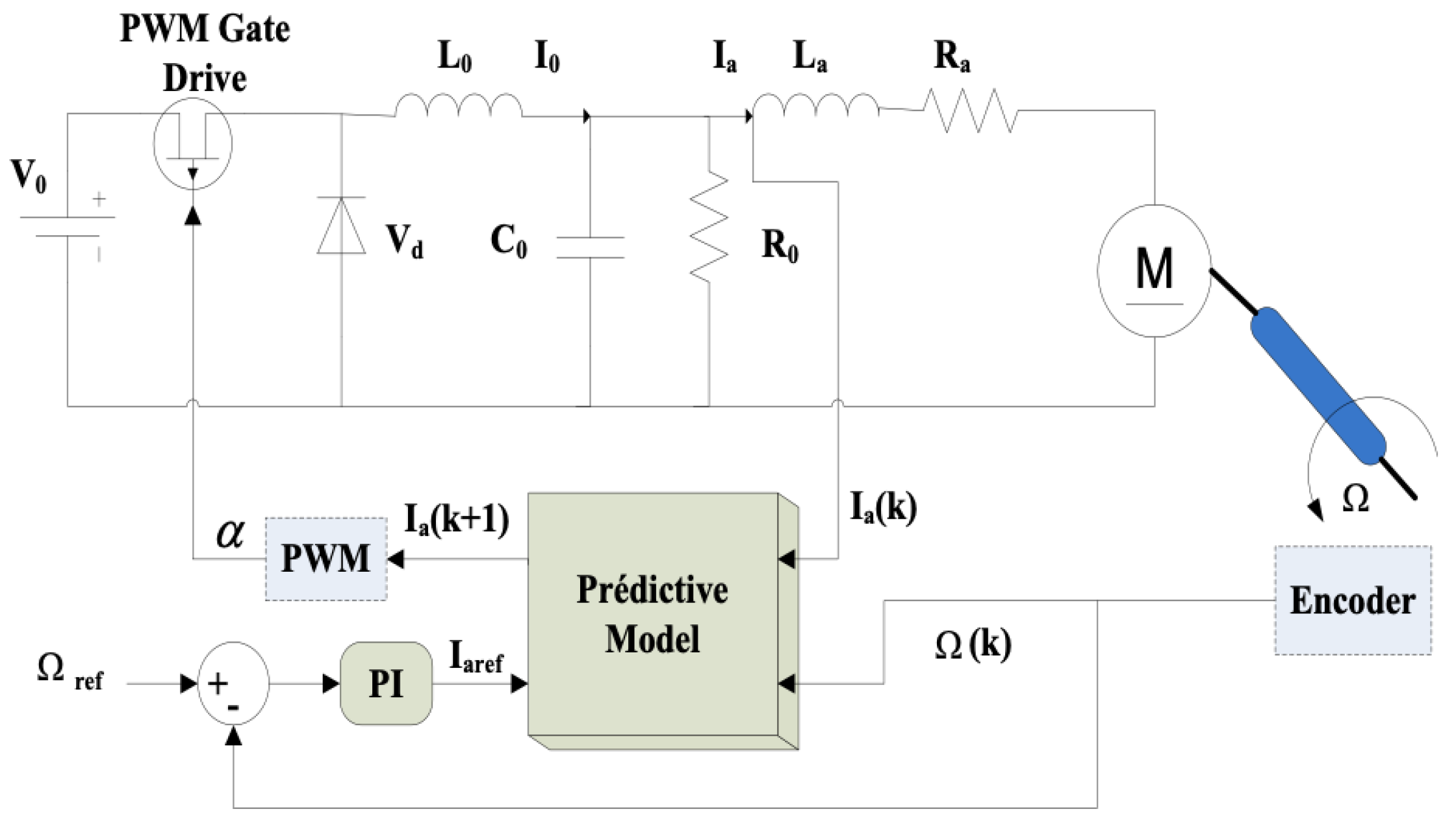

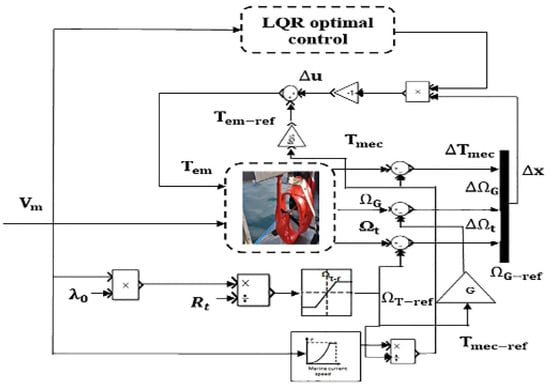

In this section, we present the design of the tidal turbine emulator, detailing the steps involved in creating the physical simulator, as illustrated in the synoptic diagram in Figure 10. Variations in marine current speed are first simulated and reconstructed, and these variations are applied to a 3 kW tidal turbine model. The resulting speed is regulated by an LQR controller and used as a reference for a direct current machine (DCM). The DCM is then current-controlled using a Model Predictive Controller (MPC), with commands applied to a MOSFET in a chopper circuit specifically designed to supply the machine’s armature.

Figure 10.

Block diagram of a tidal turbine emulator.

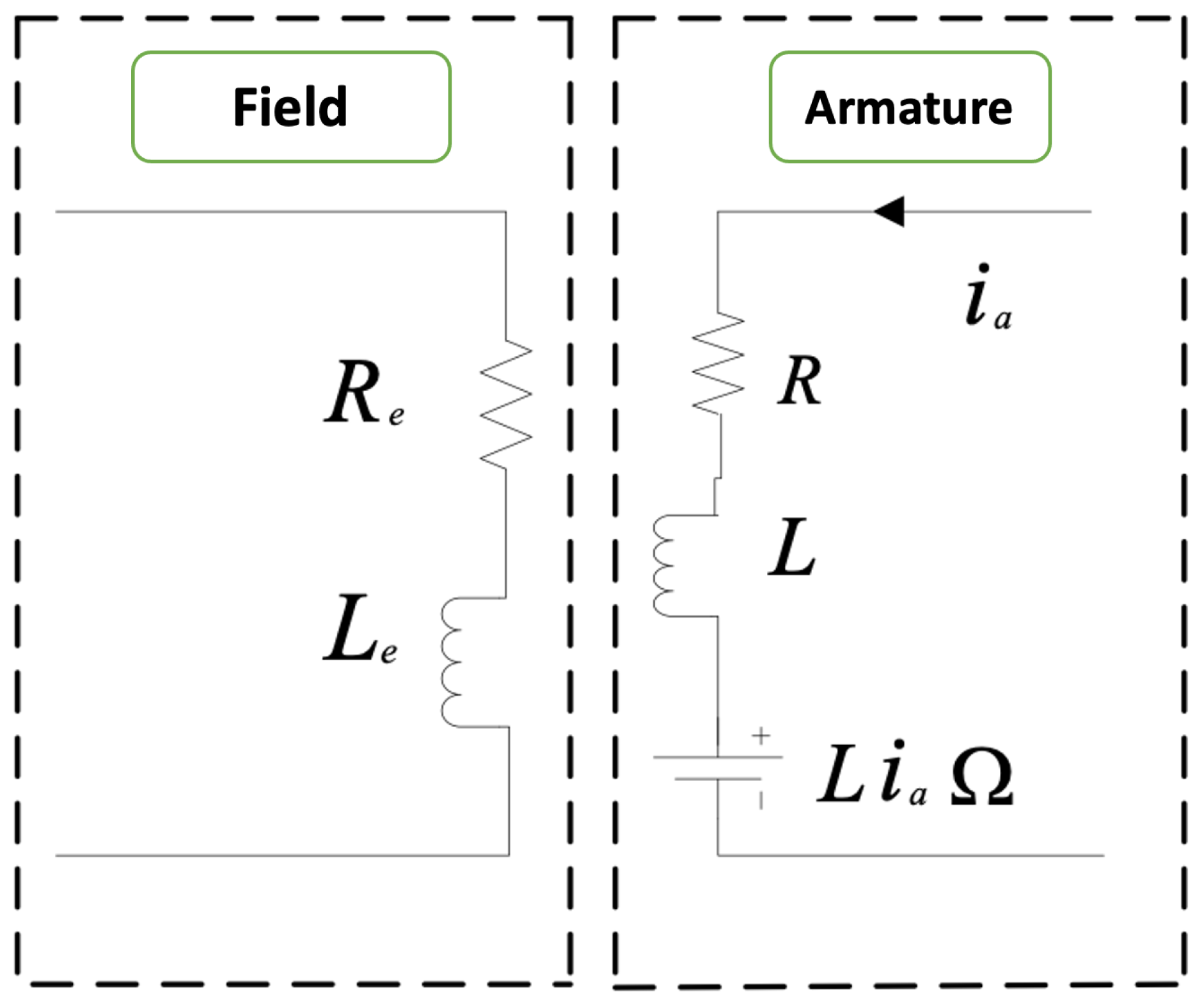

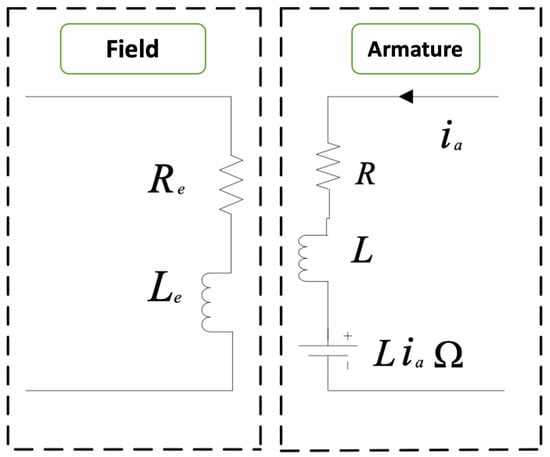

5.1. DCM Model

The Direct Current Motor (DCM) is a rotating machine which exploits the fact that a conductor placed perpendicular to a magnetic field and carrying a current move by mowing the magnetic field: it is therefore capable of producing a mechanical force. In addition, in a separately excited DCM, as shown in the electrical model of the machine given in the Figure 11, it comprises:

Figure 11.

Electrical model of the separately excited DC machine.

- The stator carries an excitation system, a field winding or permanent magnets, which creates the flux.

- The rotor carries a winding, the armature, which is supplied by a brush-collector system. The armature, to which the voltage is applied, absorbs a current . With losses taken into account, it transforms the power received in this way into mechanical power developing an electromagnetic torque C at an angular speed .

- Rotation of the armature in the flux field generates an e.m.f there E:

It can be seen that, except at very low speeds where the voltage drop can not be neglected in front of , the speed is roughly proportional to the supply voltage and inversely proportional to the flux.

The mechanical equation of the DCM can be written as follows:

where:

- : Electromagnetic and resistive torque of the DCM, (N·m).

- : Moment of inertia of the DCM [Kg·m2].

For a separately excited motor, the electrical diagram is shown in the Figure 11, and the state model can be written as follows, based on Equations (35) and (37) above:

5.2. Buck Converter Model

To vary the speed of rotation of the motor, we used a Buck-type series chopper (a single Quadrant), the structure we will study is shown in the figure, where we use a freewheeling diode D to play the role of K2, a switch symbolized here as a power IGBT also unidirectional in current, controlled on closure and opening to play the role of K1 with a duty cycle , and a DC input voltage source . The state representation of the Buck converter can be written in the following form:

5.3. Control and Regulation

The control part of a tidal turbine emulator is structured into two complementary sub-systems, each of which plays an essential role in the optimal operation of the system. The first part is dedicated to maximizing the power extracted from the marine current, using a maximum power point tracking (MPPT) strategy based on.

This control dynamically adjusts the system parameters to optimize energy efficiency, by adapting to variations in hydrodynamic conditions. The second part ensures that the speed of the direct current machine (DCM) is precisely controlled according to a given setpoint. Using appropriate regulation techniques, this control ensures that the speed of rotation of the DCM corresponds exactly to that simulated by the turbine model, enabling faithful emulation of the dynamics of the tidal turbine system. These two components work in an integrated way to effectively reproduce the behaviour of a real tidal turbine under controlled conditions.

5.3.1. MPPT Control

One of the major challenges in designing a kinetic energy extraction system is maximizing the mechanical power output. This requires the tidal turbine blades to operate at an optimal rotational speed. Therefore, it is necessary to regulate the turbine’s rotational speed to maintain the optimum operating point. The most effective method, widely used in wind energy systems and adopted in this work, is Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT). This control strategy maximizes the generated power by adjusting the turbine’s rotational speed to its reference value, based on knowledge of the maximum power coefficient. In other words, it maintains an optimal tip-speed ratio regardless of variations in the marine current, while assuming a fixed blade pitch angle.

The control strategy operates by regulating the generator’s electromagnetic torque to adjust the mechanical speed and thereby maximize the electrical power output. In this control mode, variations in marine current speed are considered as disturbances to the reference setpoint, resulting in corresponding variations in the generated power. To achieve maximum power generation, a control system is implemented based on determining the reference turbine speed. This reference speed is proportional to the marine current speed and depends on the optimal tip-speed ratio, , which corresponds to the maximum power coefficient, . The relationship is expressed by the following equation:

The speed of the reference generator is obtained by multiplying the speed of the reference turbine by the gain of the gearbox.

This reference generator speed will be compared with its output speed, so the electromagnetic torque appearing on the generator shaft must be adjusted. To achieve this, MPPT control offers the possibility of using controllers to help regulate the system. In this work, we use a control system based on linear feedback control of the LQR type. The control laws that can be applied to zones 2 and 3 (Figure 8) as a function of marine current speed: when , the aim of control in this zone is to operate the tidal turbine at maximum efficiency. The power coefficient must then be maintained at its optimum value . This is achieved by acting on the electromagnetic torque of the generator, bringing to its optimum value , which amounts to acting on the rotation speed and reducing its variations around its reference value , as expressed in Equation (44). The controller must minimize fluctuations in the mechanical torque which can have an impact on the quality of the electrical power generated (although this impact is less significant in this zone than in the others).

With:

The reference values for electromagnetic and mechanical torques in zones 1 and 2 are calculated as follows:

Linearization of the aerodynamic torque, as presented in Section 3, allows Equation (49) to be rewritten in the following form:

The proposed control strategy aims to minimize the quadratic regulator of the LQR control:

Figure 12 shows a schematic diagram of the controlled system during operation.

Figure 12.

Block diagram of the system controlled during operation [52].

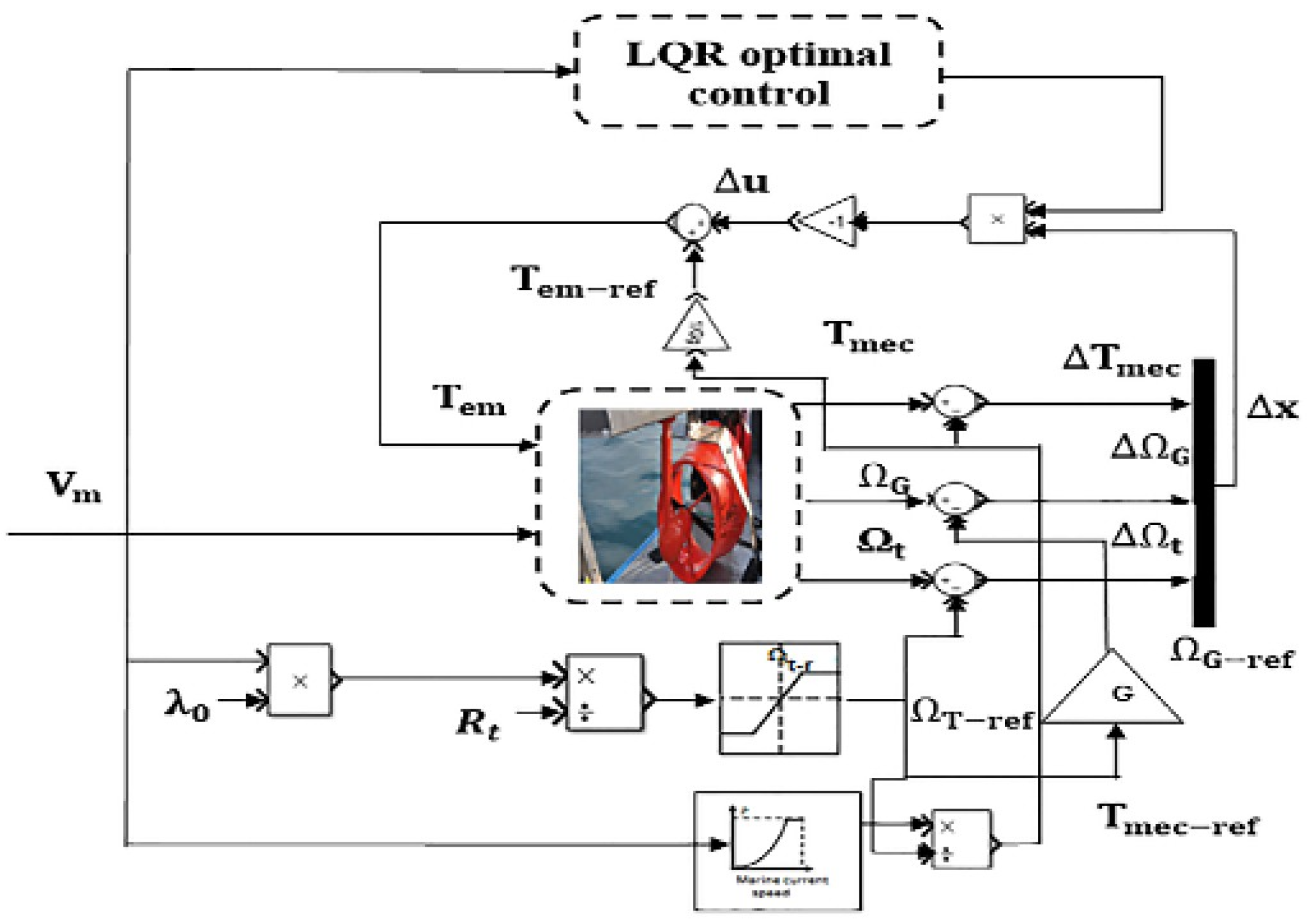

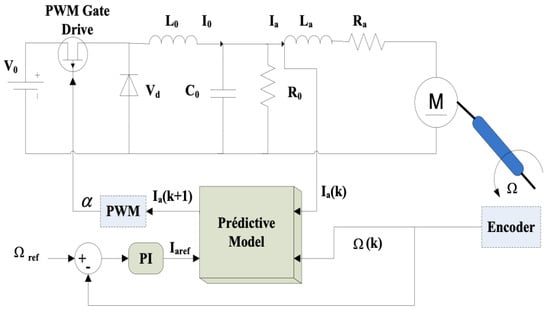

5.3.2. Control of the DC Machine

In this section, we focus on the modeling and control of the DCM powered by a flyback converter. To emulate the behavior of a tidal turbine, it is necessary to know the mechanical torque applied to the turbine generator shaft. The synoptic diagram of the strategy for determining the reference speed, whose equations were presented in Section 4, is shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

The control structure of the DC motor driven by a down converter under the predictive control algorithm.

The output of the turbine model is the rotational speed, which serves as the reference speed for controlling the machine’s rotation. The objective of the control system is to regulate the speed despite the presence of resistive torque, using measurements of the armature current and the machine’s rotational speed. To achieve this, an external loop is implemented to control the speed reference, using Model Predictive Control (MPC), while an internal loop regulates the armature current to prevent excessive currents that could damage the rotor circuit. The internal loop is implemented using a proportional-integral (PI) controller.

where:

- : the estimated reference current,

- : the measured current,

- : the measured speed.

6. Our Experimental Results

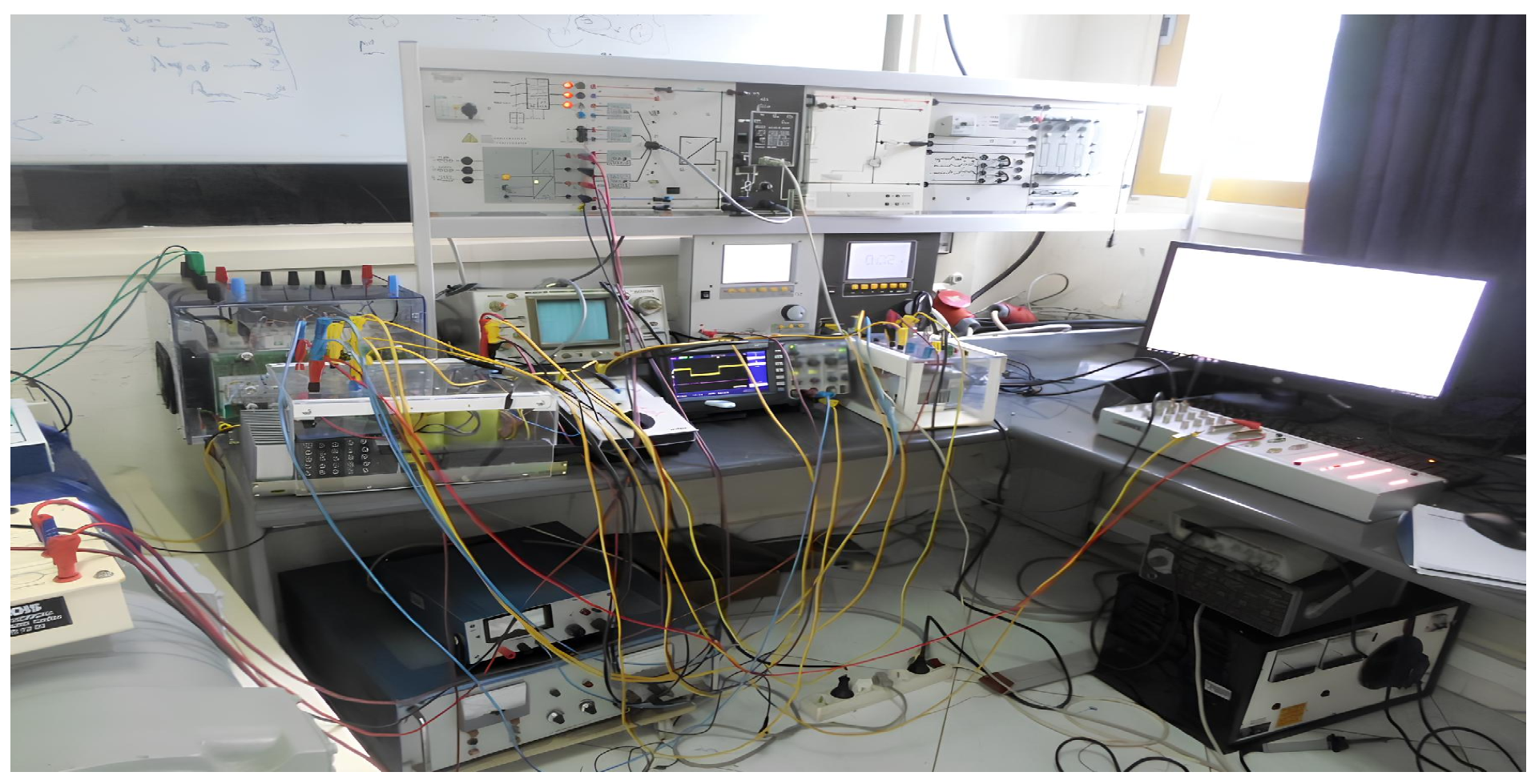

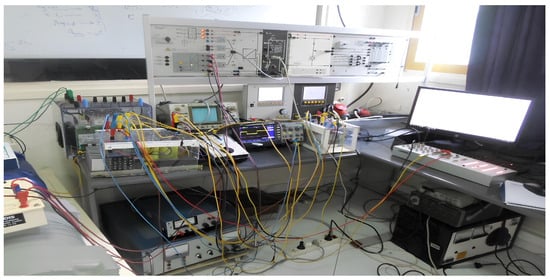

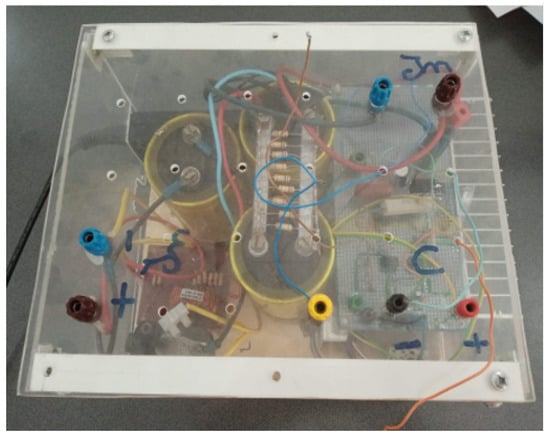

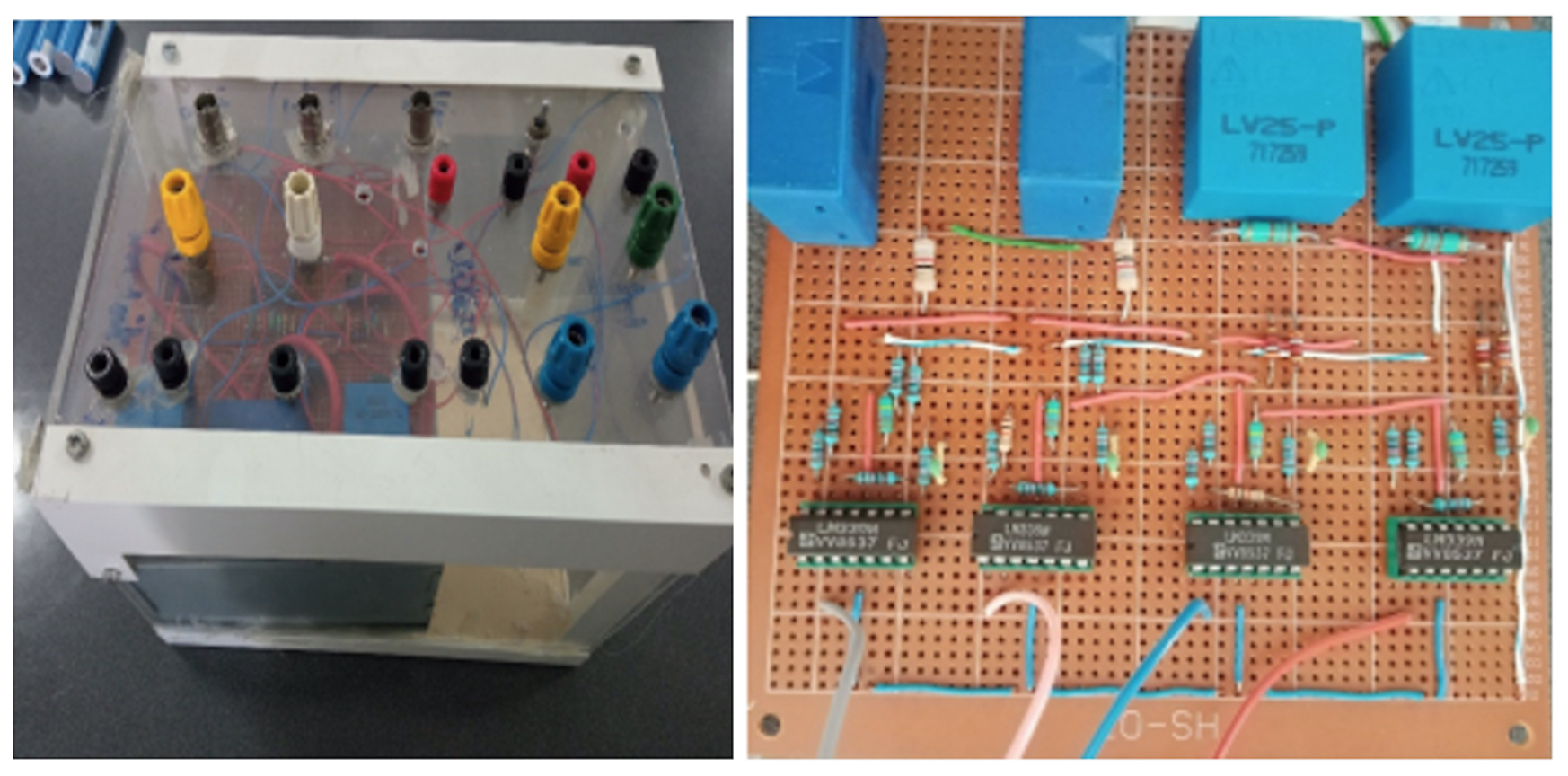

The experiments were conducted on a test bench developed by the Renewable Energy and Power Electronics team at ENSMR. Figure 14 shows a photograph of the experimental setup used for developing a tidal turbine emulator that replicates the behavior of a real tidal turbine. The bench is based on the dSPACE 1104 platform but can be extended to other computing platforms, such as FPGA. It allows the testing of multiple control algorithms and, with minor modifications, can be adapted to control different types of electrical machines.

Figure 14.

Experimental testbed designed for tidal turbine emulation.

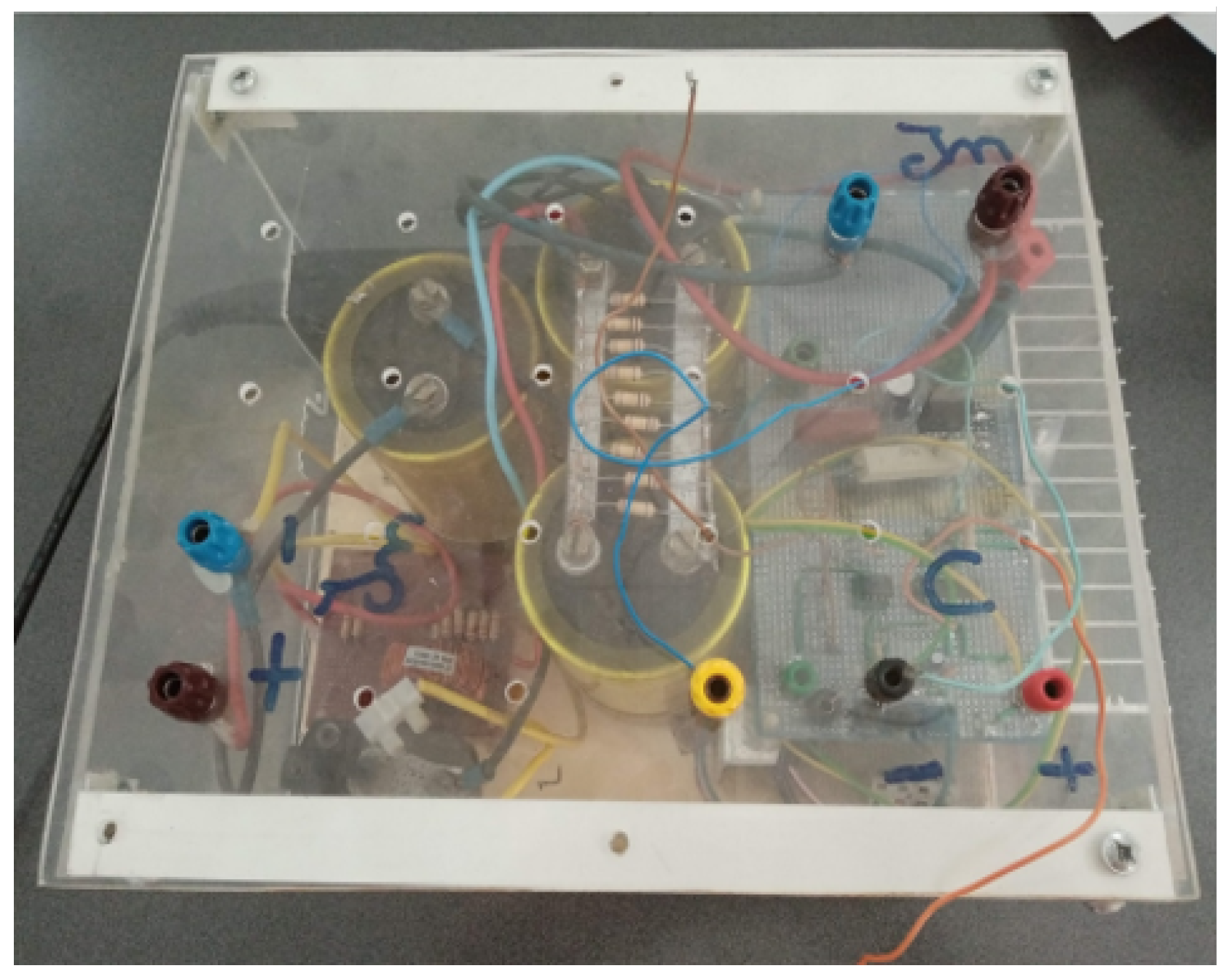

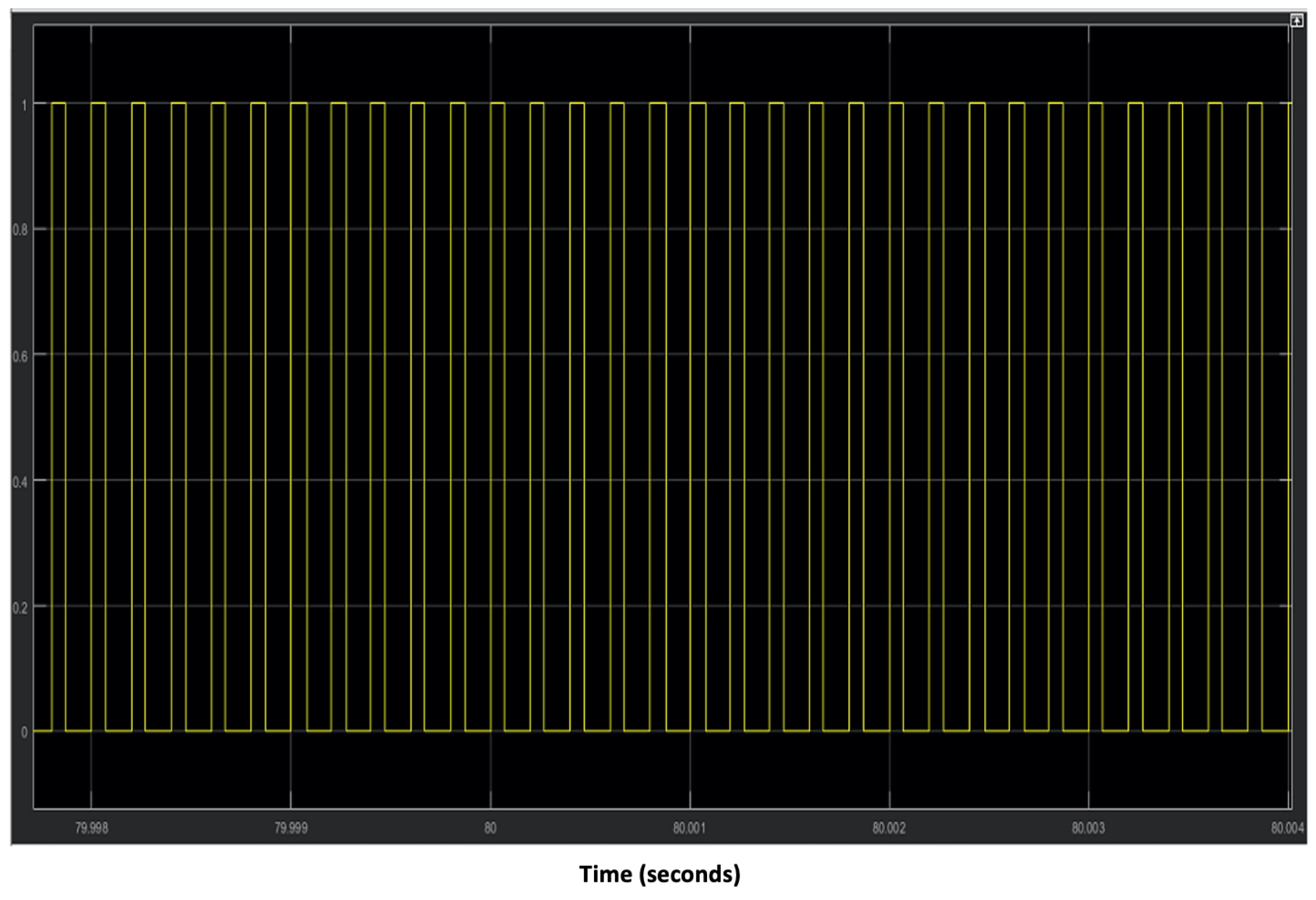

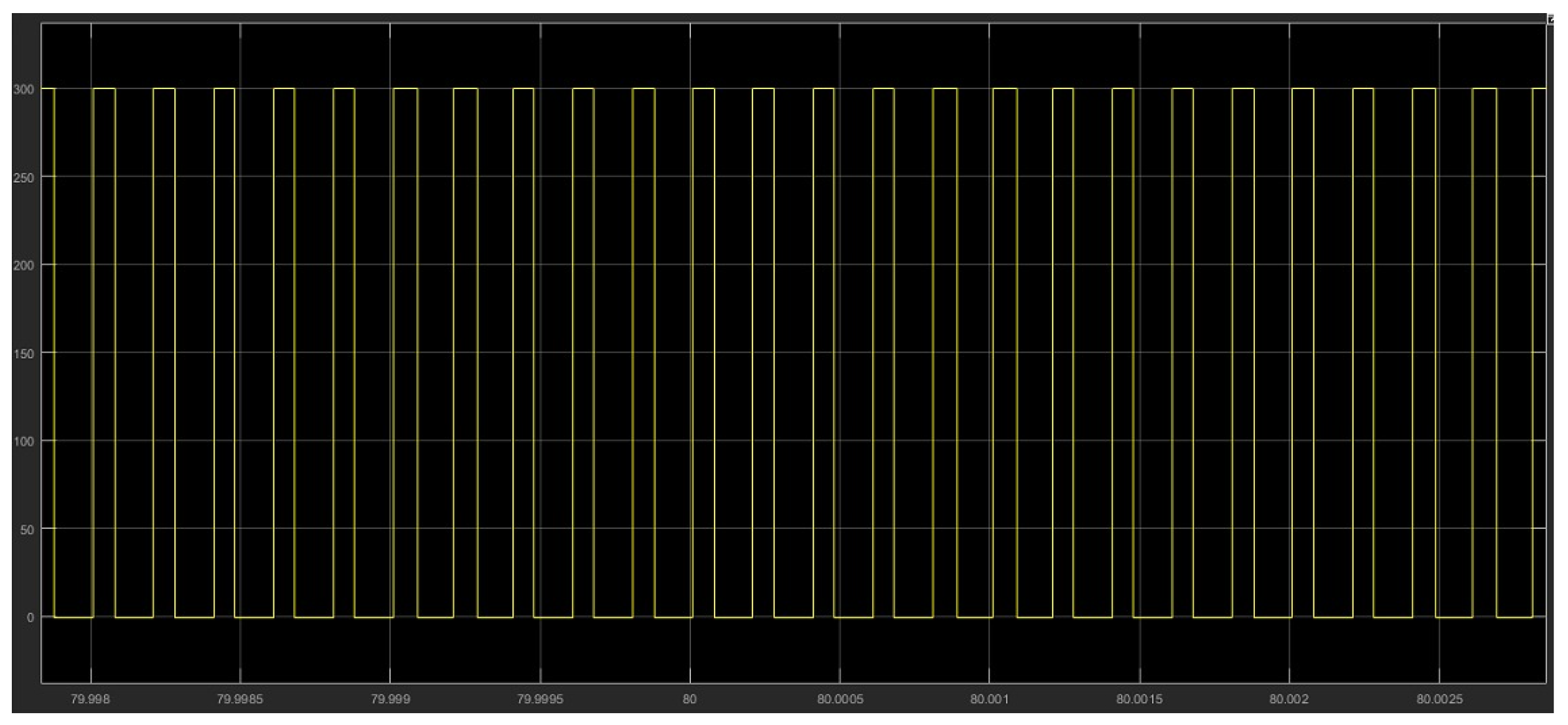

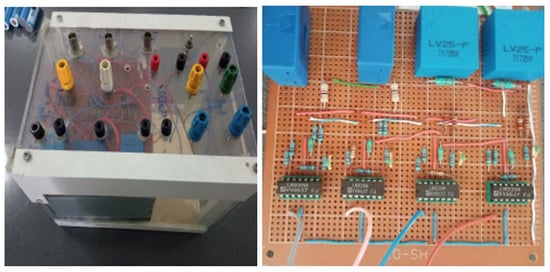

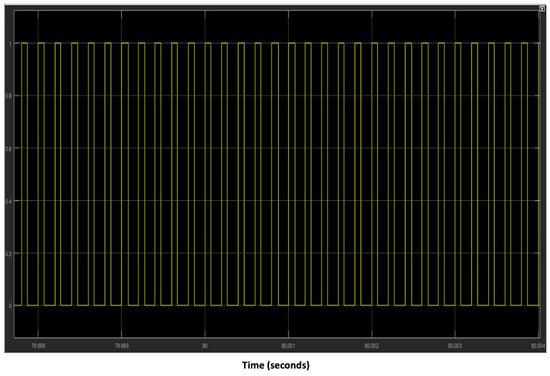

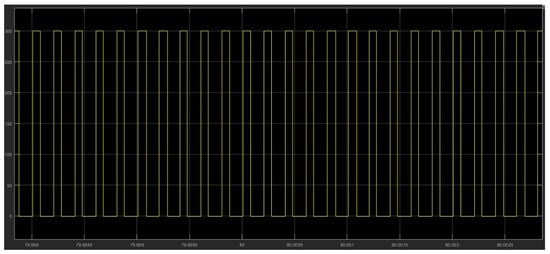

In order to experimentally validate the results of the control of the tidal turbine emulator based on a 3 Kw mcc, the predictive control algorithm is implemented using dSpace 1104 running on MATLAB-Simulink software R2020b. via Real-Time Interface (RTI). The chopper designed in the laboratory presented in Figure 15, is supplied by a variable DC voltage source with an RLC filter, and an RC filter at the motor terminal to discharge the current at the time of motor stoppage. The chopper regulates the armature of the DCM using a MOSFET capable of withstanding a maximum voltage of 1200 V and a current of approximately 25 A, with a starting voltage of 15 V. An antiparallel diode connected between the collector and emitter acts as a freewheeling diode. The MOSFET is driven by a pulse-width modulation (PWM) signal at a frequency of 20 kHz, generated by the dedicated DS1101SL_DSP_PWM1 block from dSPACE.

Figure 15.

Photo of the chopper produced in the laboratory.

- Hp2631 fast optocoupler: this is a circuit where the electrical isolation between the control section (DSPACE) and the power section is chosen. This allows us to guarantee protection against the high currents that can occur in the power section.

- IR2110 Driver: The use of Driver circuits is highly appropriate and very necessary for controlling MOSFET-based converters. Driver circuits are used to modulate the amplitudes of the control signals between the gate and the source of the MOSFET to ensure 100% switching (on or off).

- The DCM speed, the armature current, and the armature voltage are measured using LEM sensors, as shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Photo of the measurement card designed in the laboratory.

Figure 16.

Photo of the measurement card designed in the laboratory.

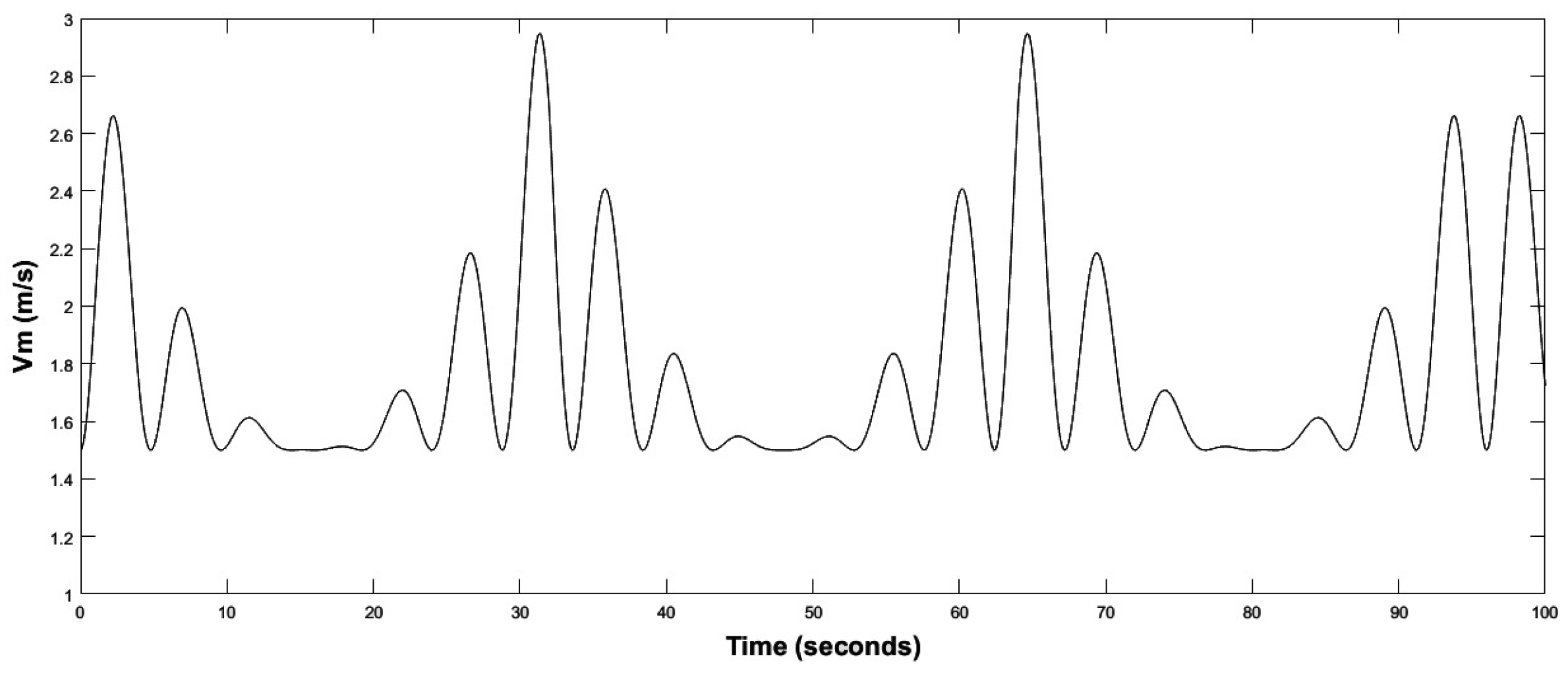

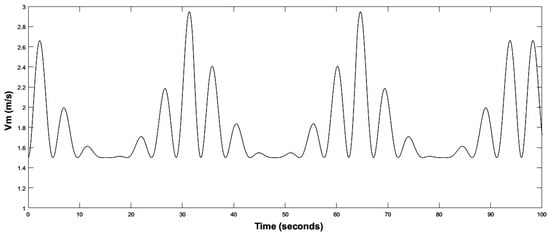

In our experimental setup, the test bench was operated with a sampling time of T = 100 µs. The variation of the marine current is characterized by a periodic profile. To represent this behavior, a marine current speed variation profile was implemented, as shown in Figure 17. This profile enables the DCM to operate in two modes: low-speed and nominal-speed. Based on this figure, it can be observed that the system was subjected to a low marine current speed of 1.5 m/s in 3 time intervals [12 s, 20 s], [45 s, 49 s], [76 s, 83 s]. It was also subjected to a high marine current speed of 3 m/s at t = 31 s and t = 65 s. Table 2 presents the list of all key system parameters used in our study.

Figure 17.

Marine current speed.

Table 2.

The list of all key system parameters used in our study.

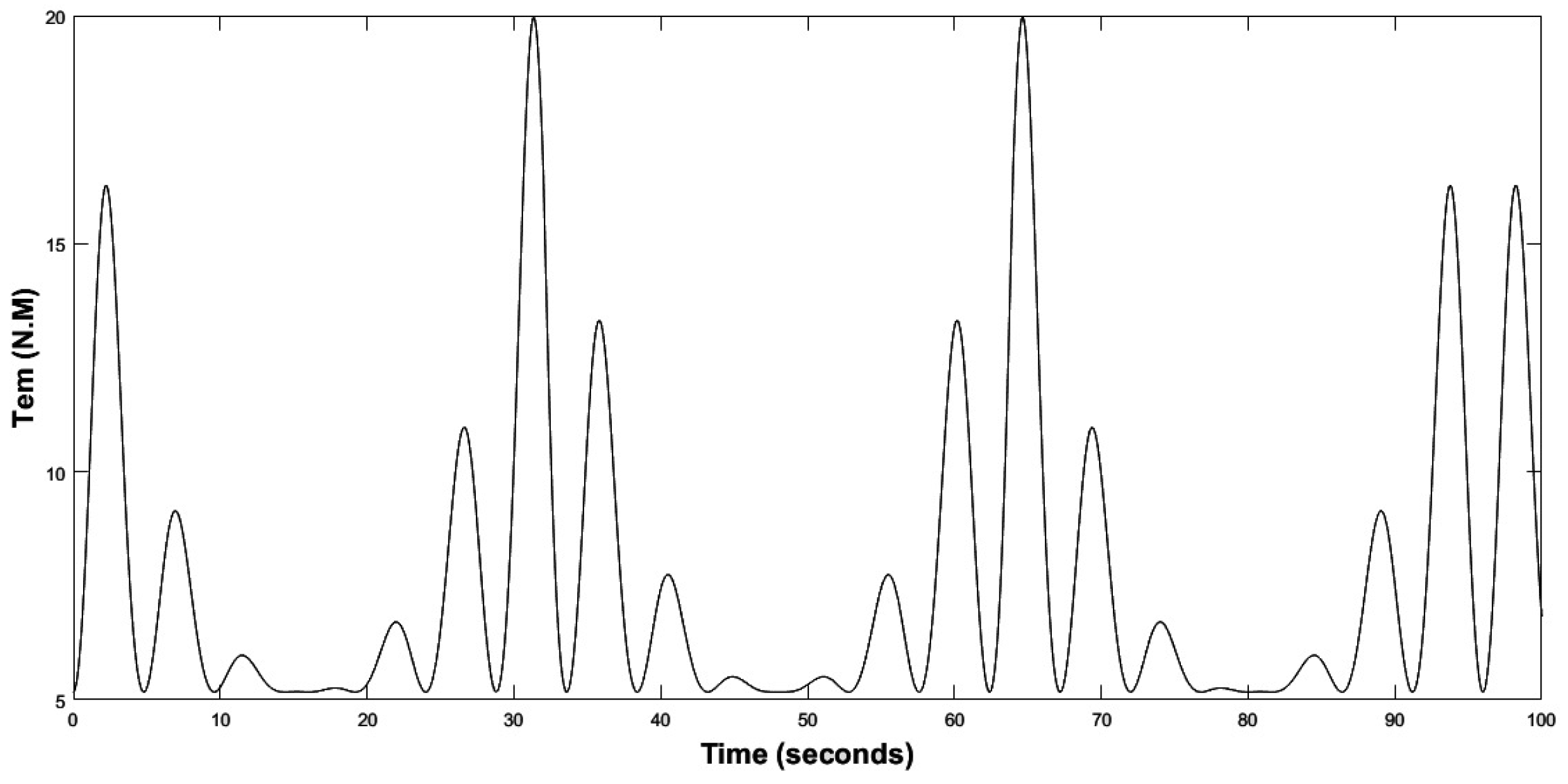

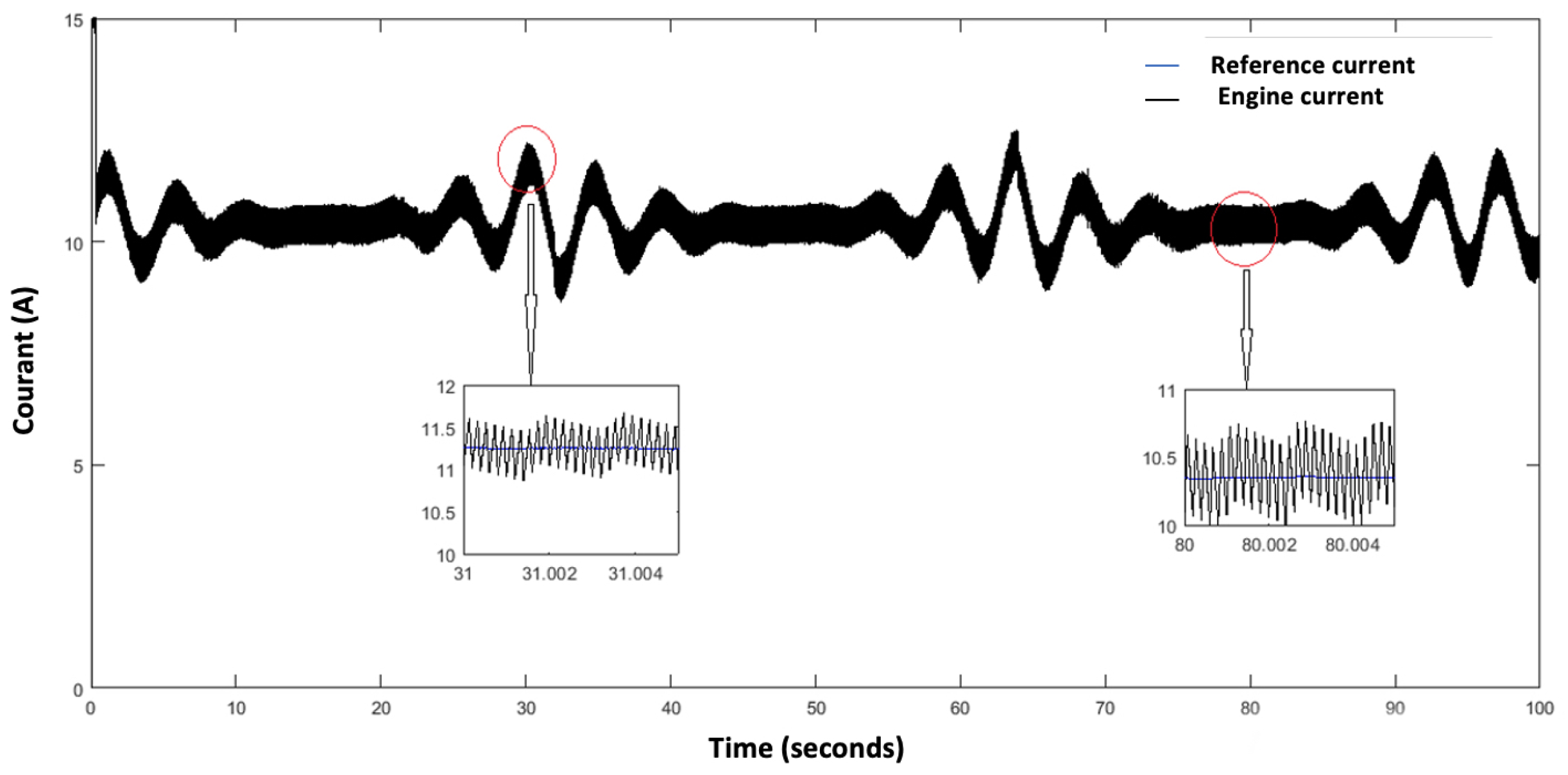

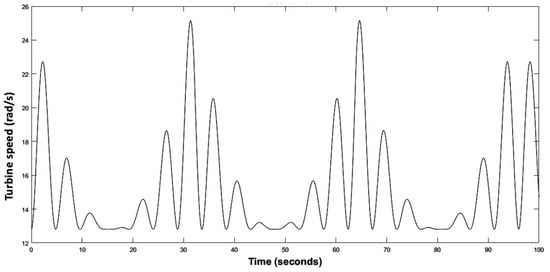

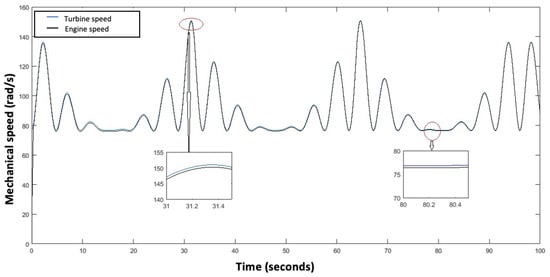

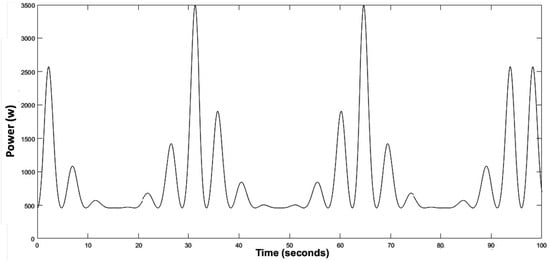

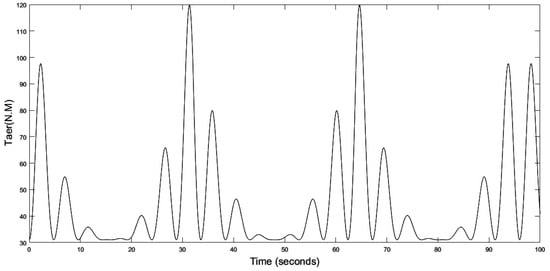

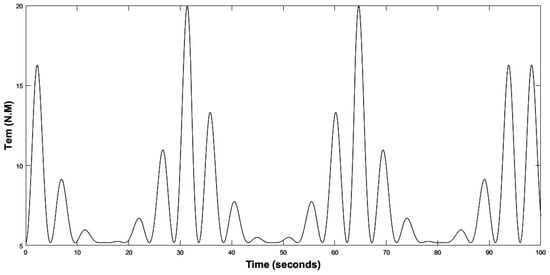

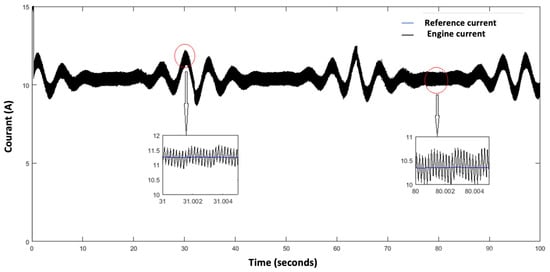

The experimental results are shown from Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22, Figure 23, Figure 24, Figure 25, Figure 26 and Figure 27. Simultaneously with the conditions of periodic change in the speed of the marine current, the mechanical speed of the turbine, the aerodynamic torque of the turbine, the electromagnetic torque, and the mechanical speed of the DCM are shown, as well as the control signal and armature voltage of the DCM motor. We note that the MPC detected the change in marine current speed and reacted accordingly.

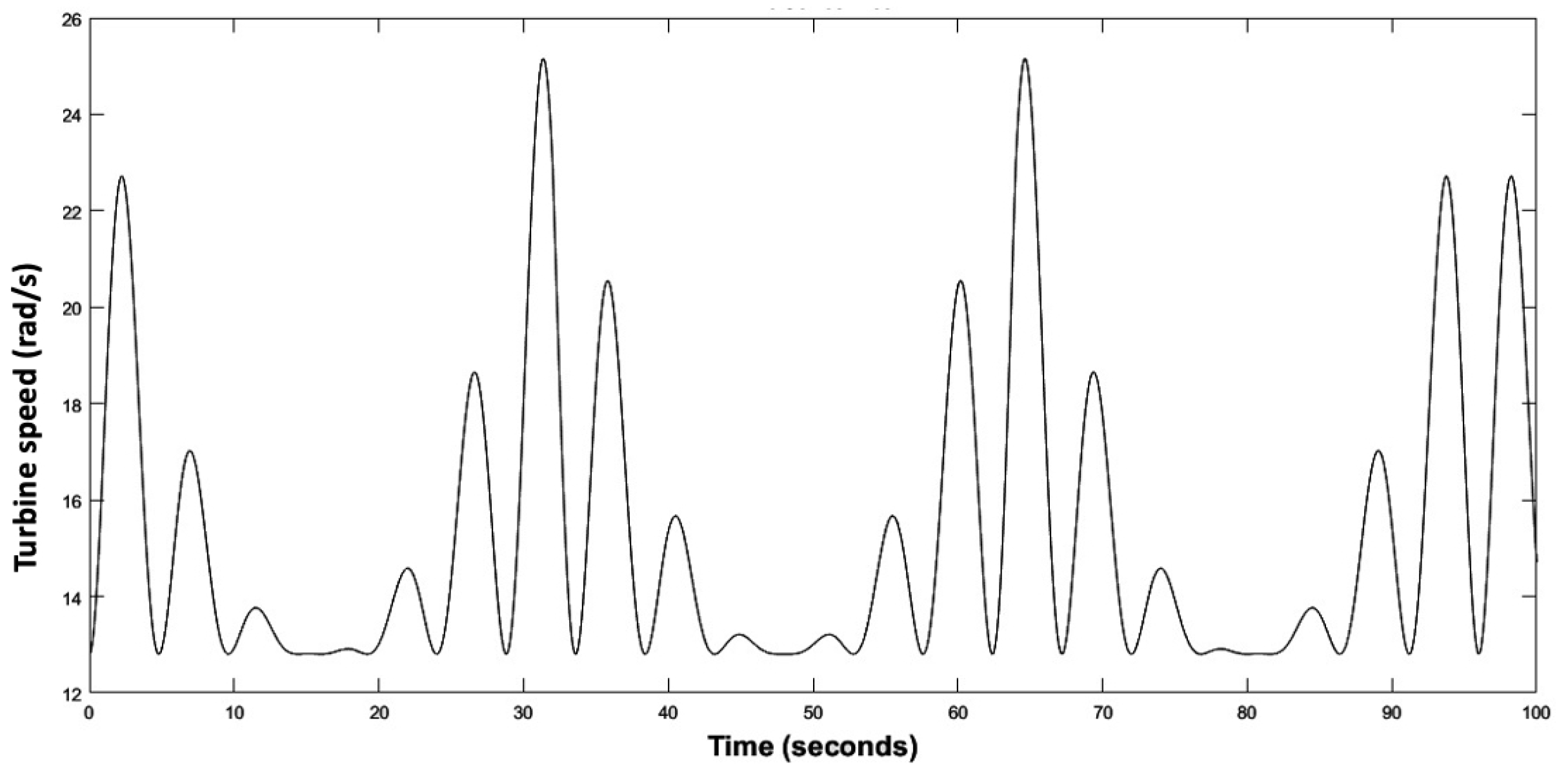

Figure 18.

Wind turbine speed.

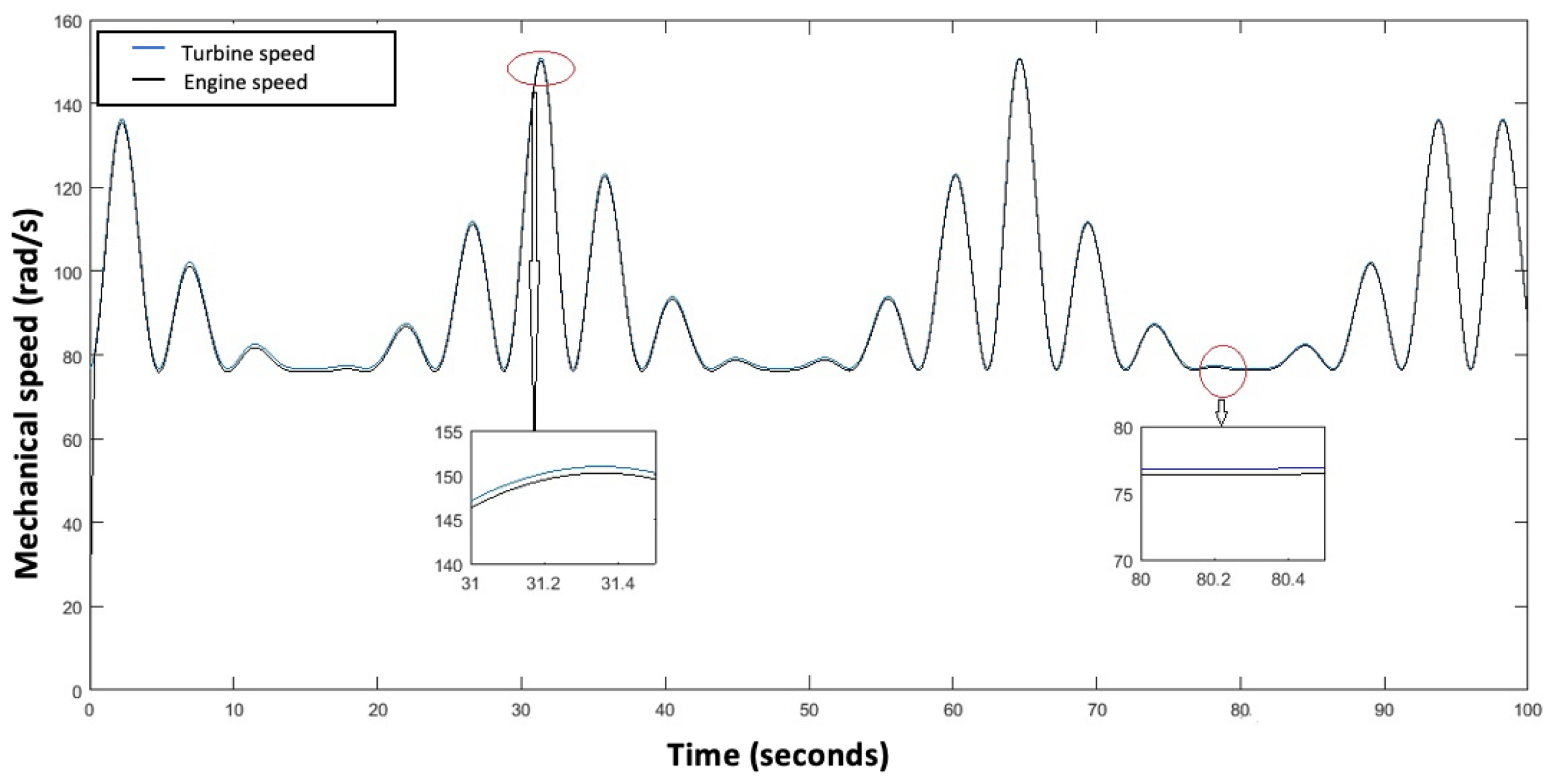

Figure 19.

Mechanical speed of turbine and DCM motor.

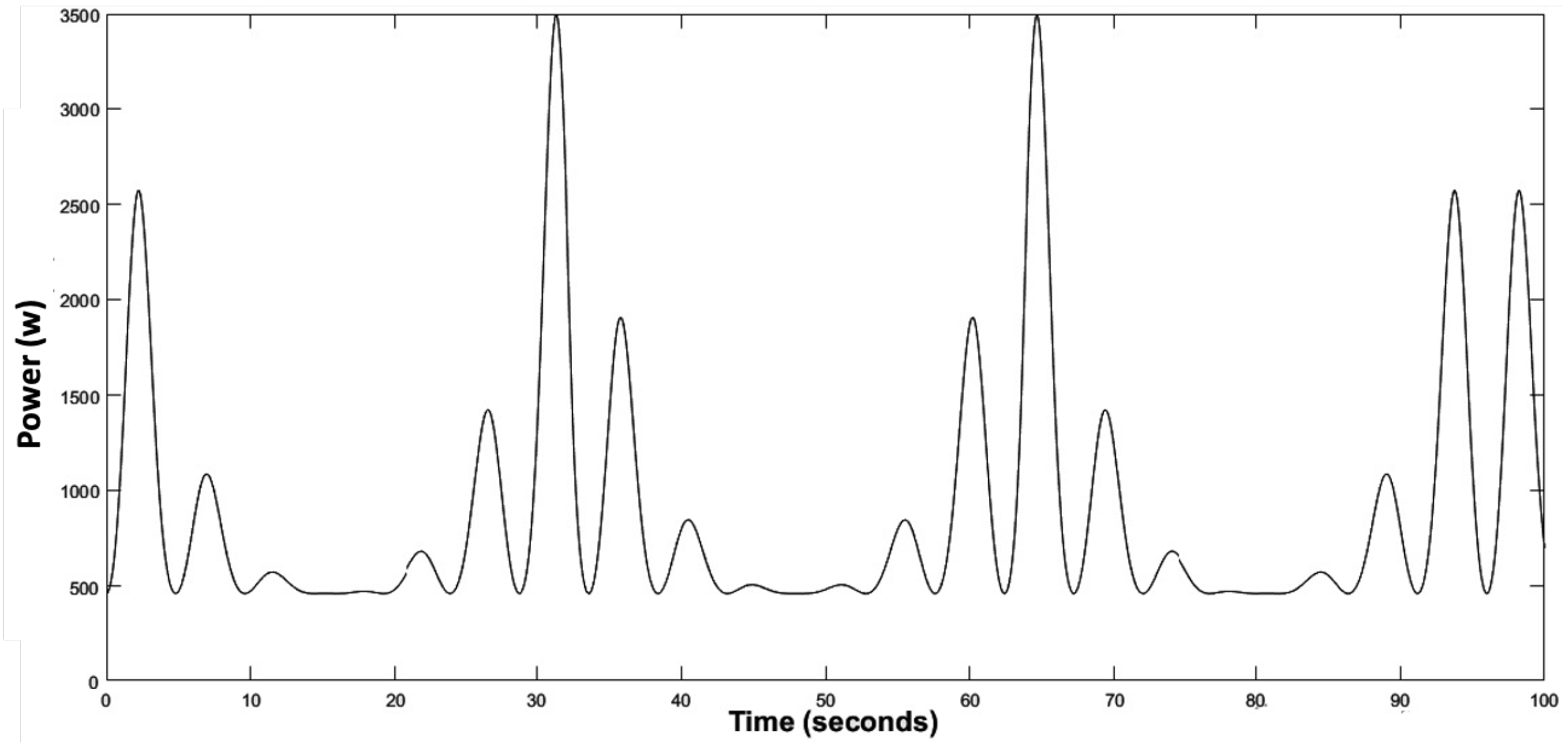

Figure 20.

Turbine aerodynamic power.

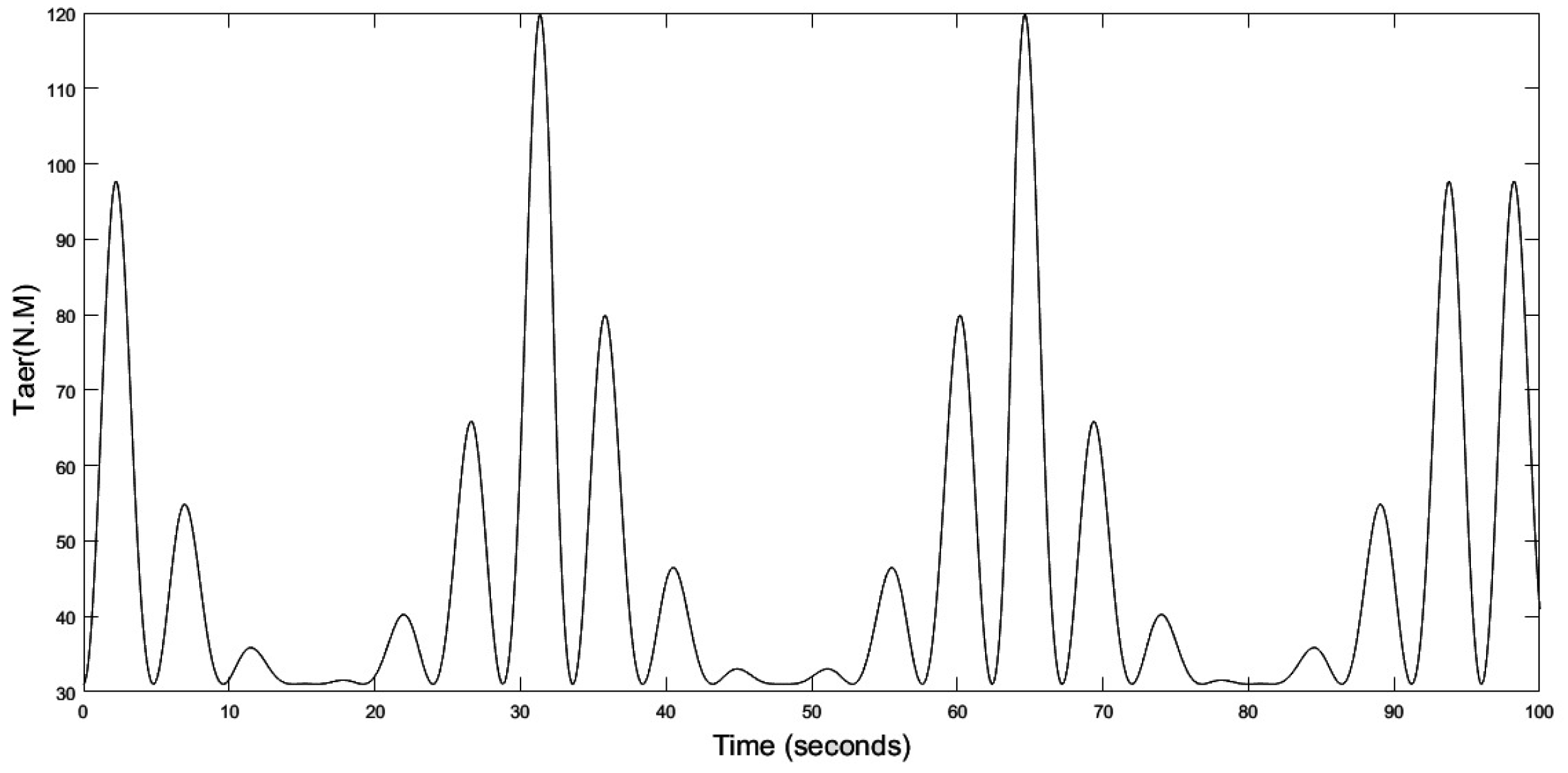

Figure 21.

Turbine aerodynamic torque.

Figure 22.

Electromagnetic torque of the turbine.

Figure 23.

Reference current and DCM motor.

Figure 24.

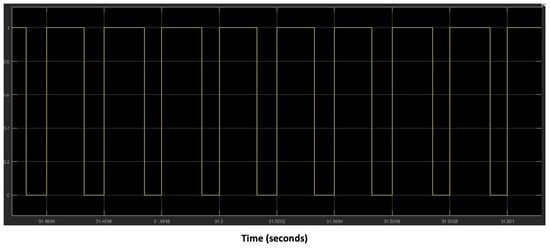

Duty cycle = 0.3, at t = 80 s.

Figure 25.

Armature voltage at the DCM motor terminal for = 0.3, at t = 80 s.

Figure 26.

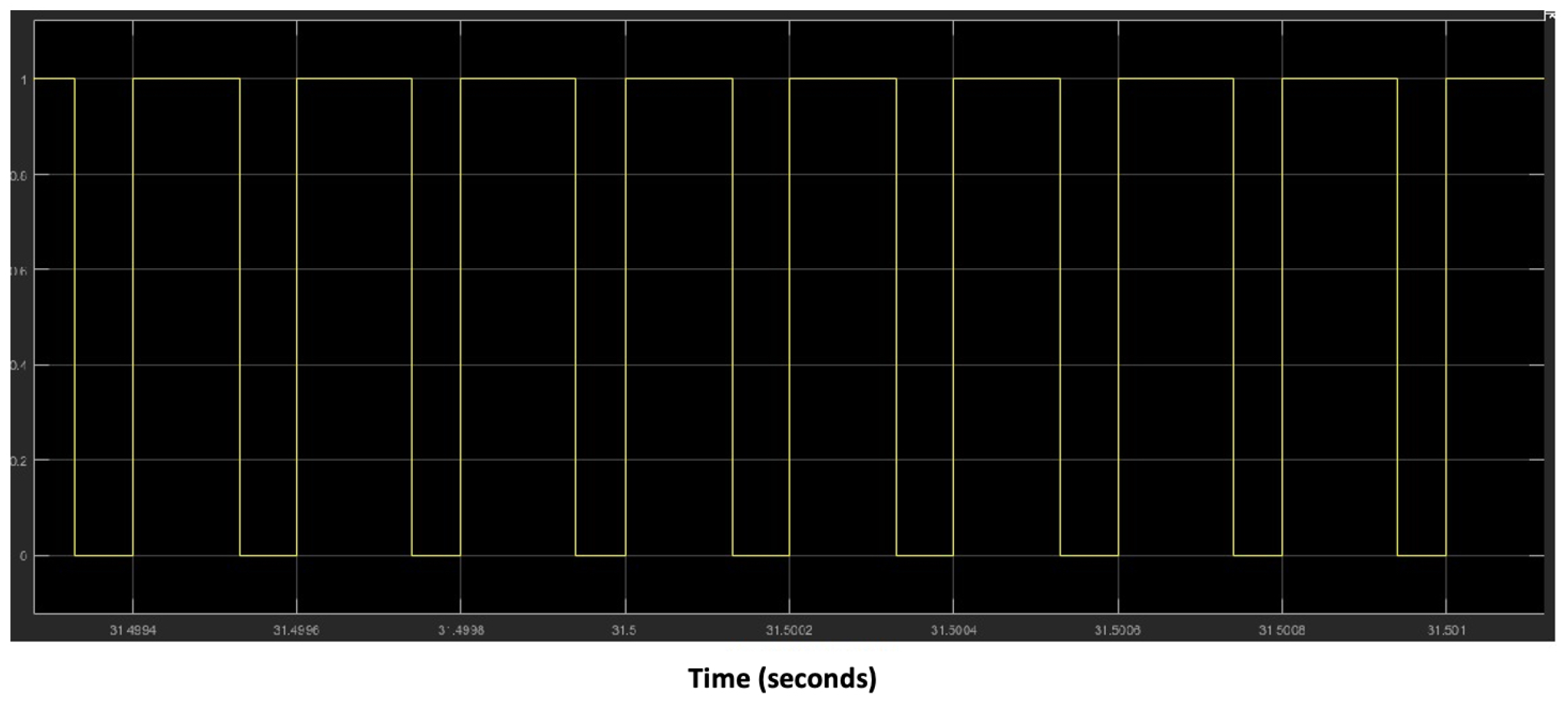

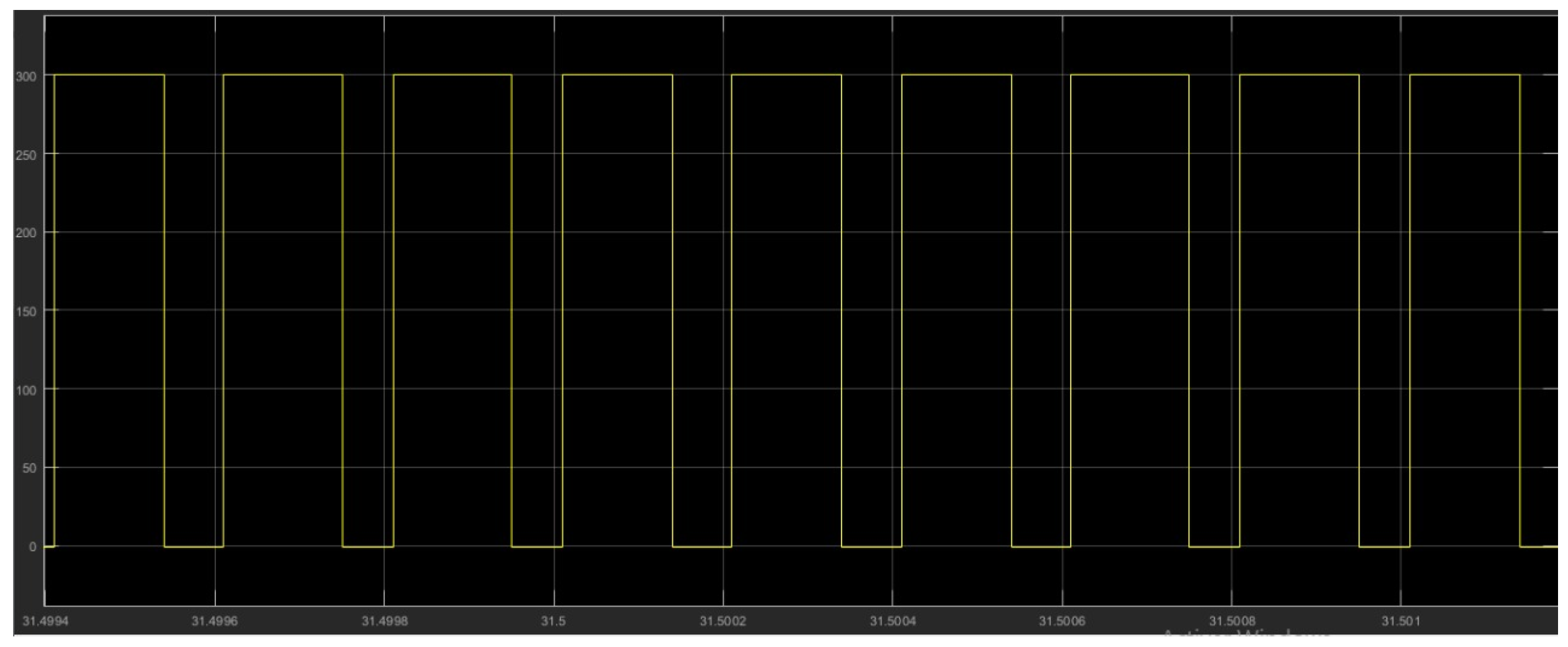

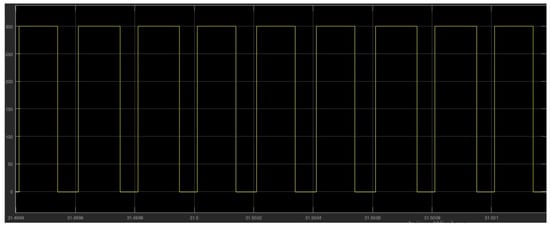

Duty cycle for = 0.8, at t = 31.5 s.

Figure 27.

Armature voltage at the DCM motor terminal for = 0.8, at t = 31.5 s.

When a low marine current speed of the order of 1.5 m/s is imposed, the tidal turbine rotates at a low speed of the order of 12.8 rad/s as shown in the Figure 18, we note that the MPPT strategy is initiated to have a which corresponds to the same theoretical value of the chapter section. At this value corresponds an optimal value of the velocity ration , the aerodynamic power extracted from the marine current as well as, the aerodynamic torque and the electromagnetic torque correspond to minimal values, as presented in Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21 and Figure 22.

The mechanical speed of the turbine shaft, the DCM speed, and the reference current, as shown in Figure 23, are measured to calculate the MPC control cost function and to generate the appropriate duty cycle applied to the Buck converter MOSFET. Finally, the armature current of the DCM can be determined. In this operating zone the value of obtained is minimal and equal to (Figure 24), the armature voltage of the DC machine is a function of the duty cycle obtained from the MPC control, which is of the order of 90 V as shown in Figure 25, and the speed of rotation of the DCM is equal to 76.81 rad/s (Figure 19).

Following the evolution of the speed of the marine current, and precisely around the nominal speed which is of the order of 3 m/s, the operating principle of the tidal current emulator is the same as in the zone where the speed of the marine current is low. The aerodynamic variables correspond to maximum values, the value of obtained is maximum and equal to 0.8 (Figure 26), the armature voltage of the DCM is a function of the duty cycle obtained from the MPC control which is of the order of 240 V as shown in Figure 27, and the speed of rotation of the DCM is equal to 150 rad/s. The zoomed sections in Figure 20 and Figure 24 highlight the two operating zones during the period shown. These results indicate that the DCM current perfectly follows its reference, meaning that the DCM rotational speed is accurately regulated to match the turbine speed, with a maximum error of . The results obtained clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of the MPC control for the regulation and operation of a tidal turbine emulator.

7. Conclusions

In this study, a real-time 3 kW water turbine simulator was designed, developed, and validated using a hybrid control strategy that combines Model Predictive Control (MPC) and Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) techniques. The proposed control framework was implemented and experimentally validated on a dSPACE 1104 platform integrated into a dedicated test bench comprising a DC machine and a power converter.

Our experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness of the hybrid MPC–LQR approach in accurately emulating the dynamic behavior of a real water turbine under controlled laboratory conditions. Quantitatively, the system exhibited high precision, with a maximum speed-tracking error of approximately 0.04 rad/s. Moreover, the controller showed fast dynamic response, achieving reference setpoints in less than 0.2 s. The LQR component successfully regulated the power coefficient () at its theoretical maximum value of 0.44, thereby ensuring optimal energy extraction from the marine current.

This work contributes significantly to the advancement of tidal energy technologies by addressing key technical challenges related to the efficient and reliable exploitation of marine currents. The results highlight the potential of hybrid predictive–optimal control strategies for real-time turbine emulation and control, supporting their deployment in marine renewable energy research and development. Nevertheless, some limitations remain. The present study is limited to operation below the rated marine current speed and relies on an emulator without a pitch control mechanism. Furthermore, although the laboratory-scale results are promising, scaling the approach to real marine environments introduces additional challenges, including highly nonlinear hydrodynamics, environmental disturbances, and complex grid-integration constraints, which were beyond the scope of this work.

In ou future research will focus on extending the proposed hybrid control strategy to incorporate pitch angle control, enabling safe and efficient operation above rated speeds and under extreme current conditions. Additionally, the integration of the MPC–LQR framework into multi-turbine farm management systems and smart grid architectures will be investigated to enhance the stability, reliability, and predictability of tidal energy contributions to the global renewable energy mix.

Author Contributions

Methodology, R.G.; Formal analysis, R.G.; Resources, R.G.; Data curation, M.B.; Validation, A.E.H.; Writing—review & editing, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Santhakumar, S.; Meerman, H.; Faaij, A.; Gordon, R.M.; Gusatu, L.F. The future role of offshore renewable energy technologies in the North Sea energy system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 315, 118775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, E.; Gkantou, M.; Malekjafarian, A.; Bali, S.; Baniotopoulos, C.; van Beeck, J.; Verma, A.S. Offshore renewable energies: Exploring floating modular energy islands—materials, construction technologies, and life cycle assessment. J. Ocean Eng. Mar. Energy 2025, 11, 1157–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yang, K.; Zhang, H.; Yang, K.; Zeng, S.; Si, K.; Zhang, Y. Challenges in tidal energy commercialization and technological advancements for sustainable solutions. iScience 2025, 28, 112348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.M.; Alhassany, H.D.S.; Vera, D.; Jurado, F. Review of enhancement for ocean thermal energy conversion system. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. 2023, 8, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, J.; Blok, K. The global techno-economic potential of floating, closed-cycle ocean thermal energy conversion. J. Ocean Eng. Mar. Energy 2024, 10, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boretti, A.; Castelletto, S. Advancements and challenges in tidal stream and oceanic current turbines: An overview of current technologies and future prospects. Mar. Dev. 2025, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taveira-Pinto, F.; Rosa-Santos, P.; Fazeres-Ferradosa, T. Marine renewable energy. Renew. Energy 2020, 150, 1160–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, V.; Bhuiyan, M.A. Tidal energy-path towards sustainable energy: A technical review. Clean. Energy Syst. 2022, 3, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, L.; Coles, D.; Piggott, M.; Angeloudis, A. The potential for tidal range energy systems to provide continuous power: A UK case study. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.; McNaughton, J.; Márquez-Dominguez, C.; Todeschini, G.; Togneri, M.; Masters, I.; Robins, P. Power variability of tidal-stream energy and implications for electricity supply. Energy 2019, 183, 1061–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.S.; Rahman, K.S.; Selvanathan, V.; Nuthammachot, N.; Suklueng, M.; Mostafaeipour, A.; Techato, K. Current trends and prospects of tidal energy technology. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 8179–8194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Benbouzid, M.; Charpentier, J.F.; Scuiller, F.; Tang, T. Developments in large marine current turbine technologies—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, J.; Nasikkar, P.; Kotecha, K.; Varadarajan, V. A review of maximum power point tracking algorithms for wind energy conversion systems. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paish, O. Small hydro power: Technology and current status. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2002, 6, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, A. A review of drivers, benefits, and challenges in integrating renewable energy sources into electricity grid. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 4775–4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Farrok, O.; Haque, M.M. Environmental impact of renewable energy source based electrical power plants: Solar, wind, hydroelectric, biomass, geothermal, tidal, ocean, and osmotic. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 161, 112279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adcock, T.A.; Draper, S.; Nishino, T. Tidal power generation—A review of hydrodynamic modelling. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A J. Power Energy 2015, 229, 755–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Zou, T.; Liu, H.; Lin, Y.; Ren, H.; Li, Q. Status and challenges of marine current turbines: A global review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasgianti; Mukhtasor; Satrio, D. The Influence of Structural Parameters on the Ultimate Strength Capacity of a Designed Vertical Axis Turbine Blade for Ocean Current Power Generators. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, B.; Tang, Y.; Huang, Y.; VanZwieten, J. Rotor blade imbalance fault detection for variable-speed marine current turbines via generator power signal analysis. Ocean Eng. 2021, 223, 108666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, R.; bin Yaakob, O.; Taheri, M.M.; Hosseinzadeh, M.; Ahmed, Y.M. An innovative configuration for new marine current turbine. Renew. Energy 2018, 120, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, D.; Rajendran, S. A review of estimation of effective wind speed based control of wind turbines. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 1046–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omkar, K.; Karthikeyan, K.; Srimathi, R.; Venkatesan, N.; Avital, E.; Samad, A.; Rhee, S. A performance analysis of tidal turbine conversion system based on control strategies. Energy Procedia 2019, 160, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhezzar, B.; Siguerdidjane, H. Comparison between linear and nonlinear control strategies for variable speed wind turbines. Control Eng. Pract. 2010, 18, 1357–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhezzar, B.; Siguerdidjane, H. Nonlinear control of a variable-speed wind turbine using a two-mass model. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2010, 26, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Purwar, S.; Kishor, N. Non-linear sliding mode control for frequency regulation with variable-speed wind turbine systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 107, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Cardenas, R.; Molinas, M. Optimal LQG controller for variable speed wind turbine based on genetic algorithms. Energy Procedia 2012, 20, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Stol, K. Simulating feedback linearization control of wind turbines using high-order models. Wind Energy 2010, 13, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakharzadeh, A.; Jamshidi, F.; Talebnezhad, L. New approach for optimizing energy by adjusting the trade-off coefficient in wind turbines. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2013, 3, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, F.; Bahmani, H. Power regulation and control of wind turbines: LMI-based output feedback approach. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2017, 27, e2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.S.; Oyedeji, M.O. Optimal control of wind turbines under islanded operation. Intell. Control Autom. 2016, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, M.A.; Hasanien, H.M.; Al-Durra, A.; Debouza, M. High performance frequency converter controlled variable-speed wind generator using linear-quadratic regulator controller. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2020, 56, 5489–5498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgarni, I.; El Amraoui, L. Optimal Control Strategies for Wind Energy Systems Based on DFIG: LQR-GA and Robust LQMinMax Approaches. In Pioneering Sustainable Innovations in Renewable Energy Technologies; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 237–276. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-González, W.; Montoya, O.D.; Escobar-Mejía, A.; Hernández, J.C. LQR-based adaptive virtual inertia for grid integration of wind energy conversion system based on synchronverter model. Electronics 2021, 10, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukili, Y.; Aguiar, A.P. LQR Based Control Strategies for DFIG-Based Wind Energy System. In Proceedings of the APCA International Conference on Automatic Control and Soft Computing, Porto, Portugal, 17–19 July 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 419–430. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Xu, Y.; Guo, H.; Geng, X.; Chen, H. Dynamic performance and control scheme of variable-speed compressed air energy storage. Appl. Energy 2022, 325, 119338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.; Cortes, P. Predictive Control of Power Converters and Electrical Drives; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; Volume 40. [Google Scholar]

- Annoukoubi, M.; Essadki, A.; Akarne, Y. Model predictive control of multilevel inverter used in a wind energy conversion system application. e-Prime-Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2024, 9, 100717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Niu, S.; Chau, A.M.H.; Luo, Y.; Lin, H.; Li, X. Recent advances in multi-phase electric drives model predictive control in renewable energy application: A state-of-the-art review. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Manandhar, U.; Zhang, X.; Gooi, H.B.; Ukil, A. Deadbeat control for hybrid energy storage systems in dc microgrids. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2018, 10, 1867–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C. Enhanced robust deadbeat predictive current control for pmsm drives. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 148218–148230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, S.; Leon, J.I.; Franquelo, L.G.; Rodriguez, J.; Young, H.A.; Marquez, A.; Zanchetta, P. Model predictive control: A review of its applications in power electronics. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2014, 8, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yu, C.; Guo, L.; Cao, R. Hysteresis model predictive control for high-power grid-connected inverters with output lcl filter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 63, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, P.; Kazmierkowski, M.P.; Kennel, R.M.; Quevedo, D.E.; Rodríguez, J. Predictive control in power electronics and drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2008, 55, 4312–4324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M.; Rodriguez, J.; Vazquez, S. Predictive control in power converters and electrical drives—Part I. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 63, 3834–3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sguarezi Filho, A.J.; Ruppert Filho, E. Model-based predictive control applied to the doubly-fed induction generator direct power control. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2012, 3, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.; Garcia, C.; Mora, A.; Flores-Bahamonde, F.; Acuna, P.; Novak, M.; Aguilera, R.P. Latest advances of model predictive control in electrical drives—Part I: Basic concepts and advanced strategies. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 37, 3927–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.; Garcia, C.; Mora, A.; Davari, S.A.; Rodas, J.; Valencia, D.F.; Mijatovic, N. Latest advances of model predictive control in electrical drives—Part II: Applications and benchmarking with classical control methods. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 37, 5047–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Nelms, R.M. Unified Model Predictive Control for DC-DC Buck Converters: From Start-up to Steady-State Operation. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), Atlanta, GA, USA, 16–20 March 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 2703–2707. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Scuiller, F.; Charpentier, J.F.; Benbouzid, M.; Tang, T. Power limitation control for a PMSG-based marine current turbine at high tidal speed and strong sea state. In Proceedings of the Electric Machines & Drives Conference (IEMDC), Chicago, IL, USA, 12–15 May 2013; pp. 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Toumi, S.; Benelghali, S.; Trabelsi, M.; Elbouchikhi, E.; Amirat, Y.; Benbouzid, M.; Mimouni, M.F. Modeling and simulation of a PMSG based marine current turbine system under faulty rectifier conditions. Electr. Power Compon. Syst. 2017, 45, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaamouche, R.; Redouane, A.; El harraki, I.; Belhorma, B.; El Hasnaoui, A. Optimal feedback control of nonlinear variable-speed marine current turbine using a two-mass model. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2020, 19, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.D.; Moore, J.B. Optimal Control: Linear Quadratic Methods; Courier Corporation. 2007. Available online: https://books.google.co.ma/books?id=fW6TAwAAQBAJ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Kahne, S.; Lee, E. Optimal control: An introduction to the theory and ITs applications. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1967, 12, 345–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, M.A.; Mousa, M.E.; Said, E.M.; Zaky, M.M.; Kotb, S.A. Optimal design of hybrid optimization technique for balancing inverted pendulum system. WSEAS Trans. Syst. 2020, 19, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, S.; Gupta, D.; Das, L.K. PID & LQR control for a quadrotor: Modeling and simulation. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI), Delhi, India, 24–27 September 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 796–802. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Rivera, G.H.; Amaya, I.; Cruz-Duarte, J.M.; Ortíz-Bayliss, J.C.; Avina-Cervantes, J.G. Hybrid controller based on LQR applied to interleaved boost converter and microgrids under power quality events. Energies 2021, 14, 6909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaideh, A.; Bodoor, M.M.; Al-Quraan, A. Active and reactive power control for wind turbines based DFIG using LQR controller with optimal Gain-scheduling. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2021, 2021, 1218236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagua, H. Performance Comparison of PID and LQR Control for DC Motor Speed Regulation. J. Eng. Exact Sci. 2023, 9, 19429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batten, W.; Bahaj, A.; Molland, A.; Chaplin, J. Hydrodynamics of marine current turbines. Renew. Energy 2006, 31, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, E.; Fadaeinedjad, R.; Naji, H.R.; Moschopoulos, G. Investigation of horizontal and vertical wind shear effects using a wind turbine emulator. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2018, 10, 1206–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mseddi, A.; Dhouib, B.; Zdiri, M.A.; Alaas, Z.; Naifar, O.; Guesmi, T.; Alqunun, K. Exploring the potential of hybrid excitation synchronous generators in wind energy: A comprehensive analysis and overview. Processes 2024, 12, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laha, A.K.; Putatunda, S. Real time location prediction with taxi-GPS data streams. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2018, 92, 298–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElman, S.; Verma, A.S.; Goupee, A. Quantifying tropical-cyclone-generated waves in extreme-value-derived design for offshore wind. Wind Energ. Sci. 2025, 10, 1529–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazim, S.; El Ouati, A.; Janan, M.T.; Ghennioui, A. Modeling the velocity of marine currents resources on a Tangier coastal using SWAN model. In Proceedings of the 2018 9th International Renewable Energy Congress (IREC), Hammamet, Tunisia, 20–22 March 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Mason-Jones, A.; O’Doherty, D.M.; Morris, C.E.; O’Doherty, T.; Byrne, C.; Prickett, P.W.; Grosvenor, R.I.; Owen, I.; Tedds, S.; Poole, R. Non-dimensional scaling of tidal stream turbines. Energy 2012, 44, 820–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.