Abstract

Supercapacitors based on mixed metal oxides are being developed as potential devices for large-scale energy storage applications with physical flexibility, thanks to their low cost and good electrochemical performance. This work demonstrates a novel approach to enhancing the electrochemical performance of bismuth–cerium oxide BiCeO3 (BC) through thiourea doping. The incorporation of sulfur, confirmed by EDS, induced significant structural modifications, including a reduction in crystallite size from 42.5 nm to 34.8 nm and the emergence of new diffraction planes (002) and (222) in XRD patterns. These changes, indicative of successful lattice doping, yielded a more nanostructured morphology with increased active surface area and a 20% reduction in the optical band gap. Electrochemically, the thiourea-doped BiCeO3 (BCT) electrode delivered a marked improvement, exhibiting a specific capacitance of 150 F·g−1 at 25 mV·s−1, a 17.2% increase over the pure BiCeO3 (128 F·g−1). Furthermore, BCT demonstrated superior rate capability and a 43% reduction in overall impedance, underscoring enhanced charge transfer kinetics and ionic conductivity. The synergy between sulfur-induced structural defects, increased electroactive surface area, and improved electronic structure establishes thiourea doping as an effective strategy for developing high-performance BiCeO3-based supercapacitors.

1. Introduction

The escalating global energy crisis, environmental pollution, and the rapid depletion of fossil fuels have intensified the imperative for sustainable, high-performance energy storage solutions [1,2,3,4,5,6]. This demand is further driven by the need to support intermittent renewable energy sources like solar and wind, which require efficient storage systems to mitigate fluctuations in power generation [3,5,7]. Among the various contenders, supercapacitors (SCs), also known as electrochemical capacitors or ultracapacitors, have emerged as pivotal devices capable of bridging the performance gap between conventional capacitors and batteries [6,8,9]. Their superiority is evidenced by high power density, remarkably fast charge–discharge rates, exceptional cycle life, and robust operational stability, making them ideal for a vast range of applications from portable electronics, electric vehicles, and grid storage to aerospace and medical systems [3,8,9,10,11]. The charge storage mechanism in SCs primarily falls into two categories: electrical double-layer capacitance (EDLC), which involves electrostatic ion adsorption at the electrode–electrolyte interface, and pseudocapacitance, which arises from fast, reversible Faradaic redox reactions [2,7,10,12]. The performance of a supercapacitor is intrinsically linked to the properties of its electrode materials [8,13]. While carbonaceous materials like activated carbon, carbon nanotubes, and graphene offer high electrical conductivity and surface area for EDLC, they often suffer from limited specific capacitance [2,14,15,16]. Conversely, pseudocapacitive materials, such as transition metal oxides (TMOs) and conducting polymers, can provide significantly higher capacitance but are frequently hampered by issues like high cost, poor electrical conductivity, and limited cycling stability [2,3,5,8]. Precious metal oxides like RuO2 and IrO2 exhibit excellent intrinsic capacitance, but their commercial application is restricted by scarcity, toxicity, and prohibitive cost [1,3,16]. This has driven research towards developing low-cost, abundant alternative TMOs, such as MnO2, NiO, and Co3O4 [3,4,5,8].

In this context, bismuth (Bi)-based materials have garnered significant attention. Bismuth oxide (Bi2O3) is an inexpensive, non-toxic TMO with good electrical conductivity and interesting electrochemical properties [1,12]. More complex bismuth structures, such as the perovskite-like bismuth ferrite (BiFeO3), have also been investigated due to their high chemical stability, inherent oxygen vacancies, and promising electrochemical performance [13]. Bismuth-based materials can undergo multiple reversible redox reactions, including a distinct “quasi-conversion” mechanism (Bi2O3 ↔ Bi0), which unveils a high theoretical specific capacity [11]. However, the capacitive behavior of many bismuth-based oxides remains relatively underexplored, with a need for deeper investigation into how microstructure—such as crystalline grain size and morphology—governs electrochemical performance [1,13,16]. Simultaneously, rare-earth metal oxides have emerged as a promising class of materials. Cerium oxide (CeO2), in particular, has been identified as a prospective electrode material due to its eco-friendliness, abundance, and outstanding redox properties facilitated by the facile Ce(III)/Ce(IV) transformation and high oxygen storage capacity [3,6,7,14]. The presence of mixed valence states and oxygen vacancies can be highly beneficial for pseudocapacitive charge storage [7]. However, pristine CeO2 often suffers from low electronic conductivity and structural deformation during redox cycling, which can limit its direct application [6]. A powerful strategy to overcome these limitations is the formation of composites or mixed metal oxides. The integration of TMOs with carbon matrices like graphene can synergistically combine the high pseudocapacitance of the oxide with the excellent conductivity and mechanical stability of the carbon, while also preventing the restacking of graphene sheets [12,14,15]. Furthermore, the creation of binary or ternary metal oxides, such as Mn-Ce-O or Zr-doped CeO2 (Ce0.9Zr0.1O2), has been shown to enhance electrical conductivity, introduce structural stability, and create a synergistic effect that significantly boosts specific capacitance and cycle life compared to their single-oxide counterparts [6,7,8]. This approach is particularly effective, as binary metal oxides often exhibit higher electrochemical activity and richer redox chemistry due to the complex interplay between different metal cations [6,13].

Beyond simple compositing, doping has proven to be a highly effective method for tailoring the physicochemical properties of electrode materials. Heteroatom doping (e.g., N, S) in carbon materials creates additional active sites for surface redox reactions, improving wettability and reducing charge transfer resistance [17,18]. Similarly, doping in metal oxide systems with transition metals (e.g., Co, Mn, Zr) can alter crystallinity and electronic structure, introduce oxygen vacancies, and enhance ionic conductivity, thereby improving electrochemical performance [6,7,13]. For instance, cobalt doping in bismuth ferrite systems has been shown to enhance specific capacitance and carrier mobility [13]. Innovative research has also explored the role of the electrolyte, where the use of redox-active species like thiourea in the electrolyte can introduce an additional pseudocapacitive effect, significantly enhancing the overall capacitance [19]. Moreover, thiourea itself has gained prominence as a versatile agent in materials science. It serves as a low-toxicity reducing agent for graphene oxide (GO), producing reduced GO (rGO) with good conductivity and dispersion stability [20]. Crucially, during thermal processes, thiourea decomposes into highly reactive N- and S-rich species (e.g., NH3, H2S), which can act as effective dopants to create N,S-codoped carbon frameworks or potentially dope metal oxides, thereby modifying their electronic structure and creating more active sites [17,18,20]. This dual function of thiourea (as a redox mediator in electrolytes and a doping agent in electrode synthesis) makes it a molecule of significant interest [17,19,20].

Building upon these foundational concepts, this work focuses on the development and enhancement of a novel mixed-metal oxide electrode, bismuth–cerium oxide (BiCeO3). The selection of this system is motivated by the underexplored potential of combining bismuth’s good conductivity and multi-electron redox capability [1,11] with cerium’s excellent oxygen mobility and redox activity [3,6,7], aiming to create a synergistic effect. To further enhance its electrochemical performance, we introduce thiourea as a dopant during the synthesis of BiCeO3. The rationale is multifaceted: first, to exploit the potential of the Bi-Ce oxide system, which remains relatively unexplored compared to other TMOs [1,3,12]; second, to investigate the doping effect of thiourea, which is expected to act as a source of heteroatoms (N, S), potentially incorporating into the oxide lattice or creating surface modifications that influence crystallinity, defect density, and redox activity [17,18,20]; and third, to leverage the known ability of dopants to inhibit crystal growth, reduce particle size, and increase the electrochemically active surface area, as seen in other doped metal oxide systems [6,7,13,21]. In this study, two materials were synthesized via a coprecipitation method: pure BiCeO3 (BC) and thiourea-doped BiCeO3 (BCT). The primary goal is to systematically evaluate the impact of thiourea doping on the material’s crystallinity, microstructure, morphological features, and ultimately, its electrochemical performance as a supercapacitor electrode material. By correlating the structural and morphological changes induced by thiourea doping with the resulting capacitive behavior, this work aims to provide a deeper understanding of structure–property relationships in doped mixed metal oxides and demonstrates the potential of BCT as a high-performance, cost-effective electrode material for advanced supercapacitor applications.

2. Experimental Details

2.1. Synthesis of BiCeO3

The BiCeO3 samples were synthesized using a simple coprecipitation method. Approximately 0.001612 mol of Ce(NO3)3·6H2O (Cerium(III) nitrate hexahydrate, 99.99%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 0.001443 mol of Bi(NO3)3·5H2O (Bismuth(III) nitrate pentahydrate, 99.99%, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were dissolved in 1.5 mL of a 1M HNO3 (Nitric acid, 70%, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) solution, and the mixture was diluted to a final volume of 10 mL with deionized water. The solution was then stirred at 100 °C on a hot plate until complete dissolution of the solids was achieved. Subsequently, 20 mL of ethanol (CH3CH2OH, >99.8%, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was added to the homogeneous solution, and most of the ethanol was evaporated, leaving a white precipitate at the bottom of the container. Next, 20 mL of distilled water was added to redisperse the white powder for washing purposes. Finally, the washed mixture was transferred to a crucible and calcined in a muffle furnace at 550 °C for approximately 4 h. The resulting product was collected after cooling to room temperature.

2.2. Synthesis of Thiourea-Doped BiCeO3

For the thiourea-doped BiCeO3 samples, we followed the same procedure described in Section 2.1, with the only modification being the addition of 0.001313 mol of thiourea (CH4N2S) (Thiourea, >99.0%, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) to the precursor solution composed of 1.5 mL of 1 M HNO3, diluted to a total volume of 10 mL with deionized water. The remaining synthesis steps were carried out following the same procedure as previously described.

2.3. Supercapacitor Electrodes

The supercapacitor devices were fabricated using an asymmetric two-electrode configuration. The current collectors consisted of graphene-coated stripboards. For each device, a precisely measured mass of 0.02 g of the active redox material—either pure BC or BCT—was uniformly applied to the conductive region of one stripboard, defining an active electrode area of 2.6 cm × 1.6 cm (4.16 cm2). The opposing stripboard electrode was left unmodified, serving as the counter electrode, resulting in an asymmetric device architecture. The two electrodes were separated by a dielectric spacer composed of cellulose paper impregnated with phosphoric acid (H3PO4, >85 wt.% in H2O, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Electrical connection to the external circuit was established using copper foil terminals, which were affixed to the stripboards with a carbon-based conductive paint. The entire assembly was subsequently encapsulated to form the final device, an example of which is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Example of constructed supercapacitor device.

The electrochemical characterization via cyclic voltammetry (CV) was performed directly on these complete two-electrode devices; therefore, no reference electrode was used in this configuration. To ensure statistical reliability, six identical devices (n = 6) were constructed and tested for each type of active material (BC and BCT). The reported electrochemical data represent the arithmetic mean of the measurements obtained from these six replicates.

2.4. Materials Characterization

The crystalline phases of BiCeO3 and thiourea-doped BiCeO3 were verified by X-ray diffraction (XRD) with radiation (). In addition, the morphological characteristics were analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and the optic characteristics were analyzed by UV-VIS spectroscopy. Finally, to analyze the energy density and specific capacitance of the supercapacitor devices constructed from the BC and BCT redox materials, cyclic voltammetry tests were performed at different scan rates (25, 50, 75 and 100 mV/s).

3. Results and Discussion

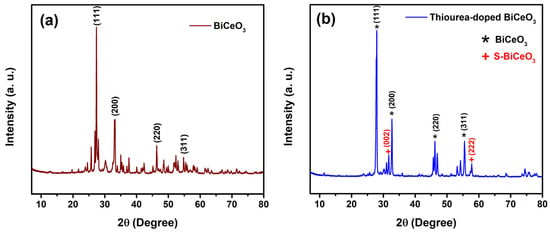

The X-ray diffraction patterns (XRD) of BiCeO3 and thiourea-doped BiCeO3 are shown in Figure 2a and Figure 2b, respectively. The results are consistent with previously reported literature for the characteristic diffraction peaks and crystallographic planes of pure BC material, along with the appearance of additional peaks at (002) and (222) in the BCT diffractogram, which are attributed to the crystalline structure of sulfur-doped BC (S-BiCeO3) after the sulfidation treatment caused by the addition of thiourea in the synthesis process [22,23,24,25,26].

Figure 2.

X-ray diffraction patterns (XRD) of (a) BC and (b) BCT.

The average crystallite size for all characteristic peaks of BC and BCT was estimated using Scherrer’s equation, yielding an average crystallite size of 42.4594 nm for BC and 34.8139 nm for BCT. The angular positions of each peak (2θ), FWHM values, characteristic diffraction planes, and the individual crystallite sizes corresponding to each peak are presented in Table 1 and Table 2 for BC and BCT, respectively. The form of the Scherrer equation used for the calculations was as follows:

where D is the crystallite size (nm), K is the Scherrer constant (0.94 for crystallites with cubic symmetry), λ is the X-ray wavelength, β is the FWHM value in radians, and θ is the Bragg angle of the analyzed peak. This form of the equation is valid only for D < 200 nm.

Table 1.

Scherrer estimation parameters for determining the crystallite size of BiCeO3.

Table 2.

Scherrer estimation parameters for determining the crystallite size of thiourea-doped BiCeO3.

In the case of BC, the diffraction peaks correspond to crystallographic planes characteristic of a cubic structure, similar to a fluorite or perovskite. In particular, the presence of the (111) peak suggests a well-defined crystalline phase. The relatively large crystallite size (~42 nm) indicates sharp and narrow peaks, which is indicative of high crystallinity and a low density of lattice defects. The relative intensities of the (111), (200), (220), and (311) peaks suggest a preferred orientation or a uniform phase distribution.

On the other hand, in the case of BCT, the appearance of the (002) and (222) peaks (absent in the pure BC matrix) suggests lattice distortion induced by doping. This may indicate changes in the lattice parameters due to the incorporation of sulfur and the possible formation of secondary phases or atomic rearrangement. The reduction in crystallite size (~35 nm) results in peak broadening (Scherrer effect), which implies a higher density of lattice defects or internal strain caused by the dopant. The variation in the relative intensity of the diffraction peaks generally reflects changes in atomic occupancy or lattice symmetry. The incorporation of thiourea into the BC matrix inhibits crystal growth, reducing the crystallite size, and introduces lattice strain. Doping leads to anionic substitution (O2− by S2−) within the lattice, the formation of vacancies or point defects, and distortion of the original cubic symmetry. All these effects, together with the reduced crystallite size and increased defect density in the doped material, enhance its catalytic activity and ionic conductivity due to the enlarged surface area and the higher density of active sites.

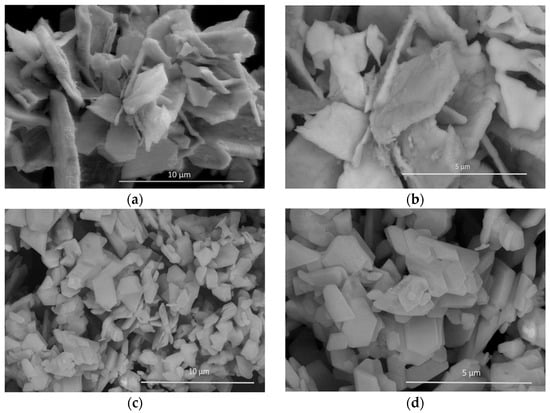

Figure 3 shows the morphological analysis of BC and BCT carried out using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). In the case of the BCT material (Figure 3a,b), smaller and possibly better-dispersed particles were observed compared to BC, which is consistent with the XRD results. The irregular structures are attributed to the growth-inhibiting effect of the dopant. A higher density of grain boundaries and surface defects was also observed, along with the possible formation of structures with a large specific surface area. The likely more homogeneous distribution may be associated with the dispersing effect of thiourea itself.

Figure 3.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of (a,b) thiourea-doped BiCeO3; (c,d) BiCeO3.

Similarly, in case of BC material (Figure 3c,d), larger particles with more developed and well-defined crystals were observed. The more crystalline structures exhibit a greater tendency to agglomerate due to uncontrolled crystal growth and display smoother, flatter surfaces, resulting in a lower specific surface area. Consequently, the particle distribution is less uniform with larger aggregates, and the defect density is lower compared to the BCT material.

The reduction in crystallite size (~7 nm) is evident at the nanometer scale in the SEM images, thereby confirming the growth-inhibiting effect of thiourea. Likewise, the lattice distortion detected in the BCT XRD pattern (appearance of new peaks at (002) and (322)) is manifested in SEM as increased morphological irregularity, possible formation of secondary phases/structures, and an increased density of grain boundaries. The morphological modification attributed to the incorporation of thiourea into the BC matrix increases the effective specific surface area and improves particle dispersion. Moreover, the rise in lattice defects correlates with enhanced surface roughness, which supports the relationship between XRD peak broadening and the increase in surface defects observed by SEM. Overall, the SEM morphology of BC and BCT is consistent with reports in the literature [27,28]. In summary, the thiourea-doped material (BCT) exhibited a higher density of surface-active sites, which enhances accessibility to reactive sites and improves charge-transfer characteristics for energy-storage applications. In contrast, the BC matrix showed greater crystallinity, resulting in improved electrical conductivity but a reduced specific surface area.

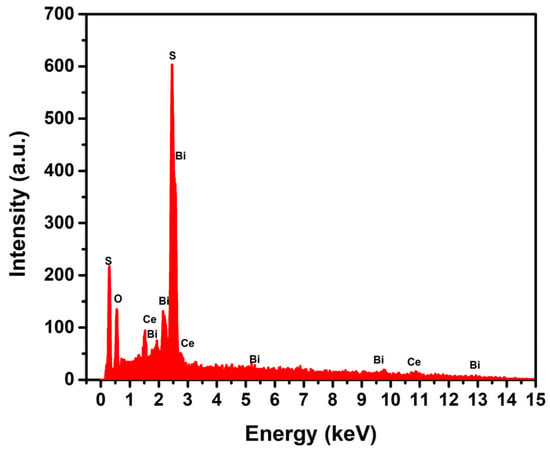

The Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) analysis of the BCT material, as presented in Figure 4, provides definitive elemental evidence to decipher the origin of these structural changes. The EDS spectrum confirms the presence of sulfur (S) within the sample, evinced by the characteristic S Kα emission line at approximately 2.3 keV. This sulfur signal is directly attributed to the decomposition of thiourea (CH4N2S) during the calcination step of the coprecipitation synthesis, which releases reactive sulfur species. The co-existence of distinct peaks for bismuth (Bi) and cerium (Ce) confirms the preservation of the host BiCeO3 matrix.

Figure 4.

Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) of thiourea-doped BiCeO3 (BCT).

The correlation between the EDS and XRD data leads to a coherent mechanistic interpretation: the incorporated sulfur atoms are actively participating in the crystal chemistry of the BiCeO3 system. The appearance of the new (002) and (222) diffraction peaks is not due to a simple physical mixture or surface adsorption but is strongly indicative of a doping-induced lattice reorganization. This phenomenon can be rationalized through two primary, non-exclusive mechanisms: anionic substitution and the formation of a distinct sulfur-containing phase. The EDS analysis confirms the elemental presence of sulfur originating from thiourea, while the XRD patterns demonstrate the profound crystallographic consequences of this incorporation, including lattice distortion, crystallite size reduction, and the emergence of a new structural order. This sulfur-induced modification of the host matrix’s electronic and structural environment is the fundamental factor behind the enhanced density of active sites and improved electrochemical performance of the BCT material, as it facilitates charge transfer and increases accessibility for redox reactions in supercapacitor applications.

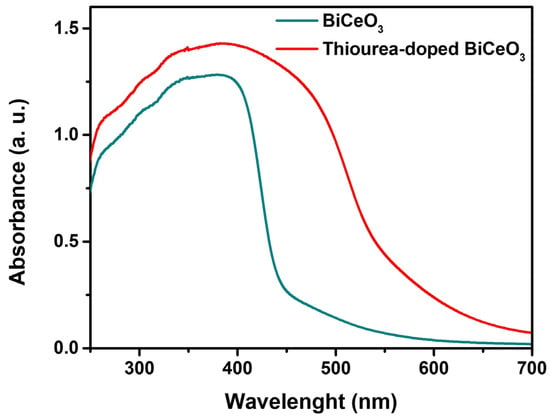

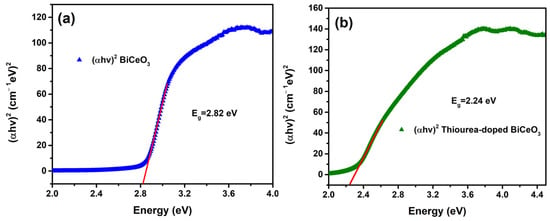

Figure 5 shows the UV–VIS spectroscopy of the BC and BCT materials. For the BC matrix, strong absorption was observed in the UV region, with an absorption edge at approximately 400 nm and low absorption in the visible range; moderate absorbance was recorded at the maximum peak, which is characteristic of a semiconductor with a moderate band gap. In contrast, the BCT matrix exhibited significantly higher absorbance across the entire UV region and a red shift in the absorption edge toward longer wavelengths. The absorbance intensity of BCT is markedly greater than that of BC, which corresponds to a reduction in the band gap caused by doping and the creation of intermediate energy states within the band gap, as shown in the Tauc plots in Figure 6a and Figure 6b, corresponding to the BC and BCT materials, respectively. The optical band gap (Eg) was reduced by approximately 20%.

Figure 5.

UV-VIS spectroscopy of BiCeO3 and thiourea-doped BiCeO3.

Figure 6.

Tauc plots of (a) BC material and (b) BCT material (direct allowed transitions).

The UV–VIS spectroscopy results are consistent with the observations from XRD patterns and SEM. The higher absorbance exhibited by BCT is attributable to its larger specific surface area, which provides a greater number of absorption sites. Defects introduced by thiourea generate in-gap (mid-gap) states that facilitate lower-energy electronic transitions. Likewise, the increased morphological irregularity and surface roughness of the doped material observed in SEM produce irregular surfaces that enhance light scattering and increase the effective optical path length within the material. Consequently, the thiourea-doped BCT shows clear advantages for applications requiring light absorption, and the reduced band gap expands its range of potential applications.

Mid-gap states were identified in the UV–VIS spectrum of the BCT material, which correspond to enhanced electron transfer. The increased defect density provides additional sites for surface redox reactions, and the morphology described above is favorable for electrochemical accessibility. Together, these findings indicate that the thiourea-doped BCT material exhibits a profile well suited for supercapacitor device applications.

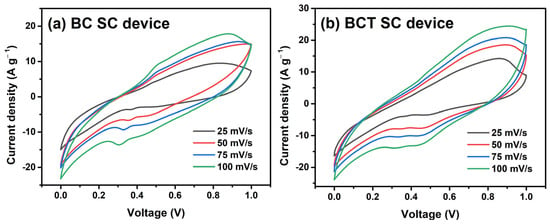

Figure 7a and Figure 7b present the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves (Voltage, V, vs. Current density, A·g−1) of the supercapacitor (SC) devices assembled with the redox materials BC and BCT, respectively, which display quasi-rectangular shapes. These shapes indicate pseudocapacitive behavior in the SC devices. The electrochemical performance of the devices was evaluated at scan rates of 25, 50, 75 and 100 mV·s−1 over 500 cycles to 1V of potential window. As the scan rate increases, the CV curves tend to become more rectangular and exhibit greater current density amplitude. This phenomenon is attributed to a reduction of oxygen-containing functional groups at the surface of the carbonaceous material (graphene in this case) and the concomitant improvement in its electrical conductivity. At higher scan rates, the quasi-rectangular profile becomes more pronounced, resembling behavior with diminished pseudocapacitive contributions.

Figure 7.

CV curves of (a) the BC material SC device and (b) the BCT material SC device.

To calculate the specific capacitance (Csp) of the redox material contained in the device from CV data, Equation (2) is used:

where Csp is in Farads per grams (F·g−1), m is the mass of the active material in grams (g), v is the scan rate in volts per second (V/s), I is the current in amperes (A), and V is the potential in volts (V). The integral represents the area under the Voltage (V) vs. Current density (A·g−1) curve obtained from the CV measurement, which corresponds to the charge stored in the material of the SC device. Using Equation (1), the specific capacitances for BC SC device were determined to be 128, 78.8, 69.6, and 66.8 F·g−1 at scan rates of 25, 50, 75, and 100 mV·s−1, respectively; whereas for the BCT SC device, the specific capacitances were 150, 119, 94, and 84 F·g−1 at scan rates of 25, 50, 75, and 100 mV·s−1, respectively, all measured after 500 cycles. These results indicate that the BCT material not only retains the capacitance of the pure BC material but further increases it, thus enhancing device performance without any additional post-treatment. The specific capacitance results correspond to those reported in previous research [29,30,31,32,33].

The considerable improvement in capacitance, observed for the BCT-based device, evident from the CV curves showing significantly larger areas and better rectangular shapes even at high scan rates, results from a multifaceted optimization confirmed by the previously described characterization techniques. The XRD patterns revealed that doping reduced the crystallite size from 42 to 35 nm and introduced structural defects that generated additional redox-active sites, while SEM analysis showed a more irregular and nanostructured morphology for the BCT material, maximizing the electrochemically active surface area. Complementarily, UV–VIS spectroscopy indicated enhanced absorbance and the presence of possible mid-gap states that improve electronic conductivity. This synergy between the increased surface area (EDLC contribution), additional redox-active sites (pseudocapacitive contribution), and improved conductivity enables more efficient ionic and electronic transport, resulting in a markedly higher specific capacitance (Csp), better retention at high charge/discharge rates, and lower internal resistance in the doped BCT material. Consequently, BCT emerges as a promising material (and electrode candidate) for high-performance supercapacitor applications.

Table 3 summarizes the capacitance values and material types reported in previous publications on supercapacitor (SC) devices. From this table, we conclude that the devices fabricated in this work using the redox-active materials BC and BCT exhibit specific capacitances ranging from 66.8 to 150 F·g−1 at various scan rates. These values are higher than those reported for several other devices/electrodes prepared with similar redox compounds in the literature.

Table 3.

Summary of electrochemical parameters for SC’s previously published in the literature and compared with the results obtained in this work.

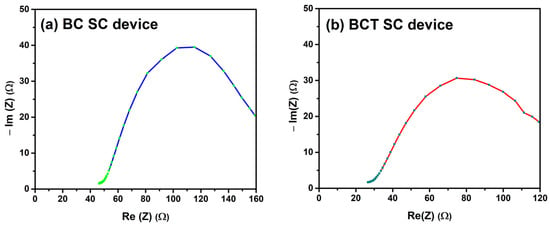

Figure 8a and Figure 8b show the Nyquist plot of the EIS (electrochemical impedance spectroscopy) results for supercapacitor devices composed of BC and BCT, respectively. The BC SC device exhibits high resistance to charge transfer, indicating that it is not well optimized. This may be due to an inadequate distribution of the surface area in contact with the electrolyte, which limits the access of electrolyte ions to the active sites [38,39,40]. In the case of the thiourea-doped BCT SC device, the impedance decreases, resulting in better charge accumulation. This improved distribution of the surface area in contact with the electrolyte leads to greater accessibility of the active sites, thus enhancing the electrochemical performance. These parameters reflect the electrochemical behavior of the devices, with a decrease in resistance indicating better conductivity in the thiourea-doped device.

Figure 8.

EIS curves of (a) the BC material SC device and (b) the BCT material SC device.

The comparative impedance analysis between the base BiCeO3 and its thiourea-doped counterpart demonstrates a profound and systematic enhancement in the material’s electrical properties. The incorporation of thiourea resulted in a dramatic reduction in the material’s overall impedance by approximately 43%, which was a key indicator of improved conductivity. This enhancement is primarily driven by a decrease in the charge transfer resistance (CTR), which signifies a much more efficient electrochemical process at the electrode interface. Additionally, doping successfully eliminated parasitic inductive effects observed in the pure sample and reduced the limitations associated with ionic diffusion. These combined improvements point towards a fundamental optimization of the material’s microstructure and electronic landscape, leading to a more conductive, stable, and electrochemically active ceramic.

The substantial improvements in electrical properties directly position thiourea-doped BiCeO3 (BCT) as a superior candidate for real-world energy storage applications. The drastic reduction in CTR and lower overall impedance are critical for achieving high power density, as they allow for significantly faster charge and discharge rates with minimal energy loss. The enhanced ionic diffusion further supports this high-power capability, while the removal of non-ideal inductive behavior suggests greater long-term interfacial stability. Consequently, devices utilizing thiourea can be expected to exhibit not only higher efficiency and faster response times but also improved reliability, marking a significant step forward in the development of advanced supercapacitors and solid-state batteries.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully demonstrates that thiourea doping is a highly effective strategy for enhancing the physicochemical and electrochemical properties of BiCeO3 for supercapacitor applications. The incorporation of sulfur into the BiCeO3 lattice (BCT), confirmed unequivocally by EDS analysis, induced profound structural and morphological modifications. X-ray diffraction analysis revealed that thiourea doping acted as a crystal growth inhibitor, reducing the average crystallite size from 42.5 nm for pure BC to 34.8 nm for BCT. Furthermore, the emergence of new diffraction planes, specifically (002) and (222), provided clear evidence of successful lattice doping and structural distortion, which increased the density of lattice defects and active sites. These structural changes were directly manifested in the material’s morphology, as observed by SEM, where the BCT sample exhibited a more nanostructured, irregular, and well-dispersed particulate nature compared to the larger, more agglomerated particles of pure BC. This morphological evolution resulted in a significantly increased electrochemically active surface area. Complementarily, UV-Vis spectroscopy revealed that doping led to a substantial 20% reduction in the optical band gap of BCT, attributed to the creation of mid-gap states that facilitate electronic transitions and improve charge carrier mobility.

The synergy of these structural, morphological, and electronic optimizations translated directly into superior electrochemical performance. The thiourea-doped BCT electrode delivered a specific capacitance of 150 F·g−1 at a scan rate of 25 mV·s−1, representing a significant 17.2% enhancement over the pure BC electrode (128 F·g−1). More importantly, the BCT electrode demonstrated excellent rate capability, retaining a much higher percentage of its capacitance at increased scan rates, which is critical for high-power applications. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy provided further evidence of the enhanced charge dynamics, showing a dramatic 43% reduction in the overall impedance for the BCT-based device. This underscores a substantial decrease in charge transfer resistance and improved ionic diffusion, leading to more efficient and faster charge–discharge kinetics.

In summary, the main quantitative achievements of this work include a ~18% reduction in crystallite size, a 20% reduction in band gap, a 17.2% increase in specific capacitance, and a 43% decrease in overall impedance. These figures collectively validate the role of thiourea as a powerful dopant. From a technological standpoint, the use of a simple coprecipitation synthesis method, coupled with the low cost and non-toxic nature of thiourea, underscores the potential for scalable and cost-effective production of BCT electrodes. The marked improvement in rate capability and the significant reduction in impedance position thiourea-doped BiCeO3 as a highly promising electrode material for the development of next-generation, high-performance supercapacitors requiring rapid energy delivery and long-term stability, with potential applications in electric vehicles, renewable energy grid storage, and portable electronics.

Author Contributions

Investigation, synthesis, characterization, writing—review and editing, Y.B.-P. and D.Y.M.-V.; investigation, characterization, data curation, resources, writing—review and editing, L.A.G.-P. and A.P.-C.; investigation, validation, data curation, writing—review and editing, E.M.-J. and E.L.-L.; investigation, data curation, visualization and supervision, A.C.-A. and A.O.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by SECIHTI grant number CBF-2025-I-2172.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Faculty of Basic Sciences, Engineering, and Technology of the Autonomous University of Tlaxcala Yael Bedolla Pluma and Luis A. Garces Patiño thanks the Secretariat of Science, Humanities, Technology, and Innovation (SECIHTI) for their master and doctoral support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BC | Bismuth–Cerium Oxide (BiCeO3) |

| BCT | BiCeO3 doped with thiourea |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| SC | Supercapacitor |

| EDLC | Electrical double-layer capacitance |

| TMO | Transition metal oxide |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| CV | Cyclic voltammetry |

| FWHM | Full Width at Half Maximum |

| RGO | Reduced graphene oxide |

| GCE | Cleaned glassy carbon electrode |

| AC | Active carbon |

| Cu@N-C | Cupper nanocrystals@nitrogen-doped carbon composites |

| CTR | Charge transfer resistance |

References

- Yang, S.; Ping, Y.; Qian, L.; Han, J.; Xiong, B.; Li, J.; Fang, P.; He, C. Flower-like Bi2O3 with enhanced capability and cycling stability for supercapacitors. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 31, 2221–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Z. Bi2O3 with Reduced Graphene Oxide Composite as a Supercapacitor Electrode. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2018, 13, 12256–12265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheswari, N.; Muralidharan, G. Hexagonal CeO2 nanostructures: An efficient electrode material for supercapacitors. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 14352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matinise, N.; Botha, N.; Madiba, I.G.; Maaza, M. Mixed-phase bismuth ferrite oxide (BiFeO3) nanocomposites by green approach as an efficient electrode material for supercapacitor application. MRS Adv. 2023, 8, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Lui, F.; Qi, J.; Gao, W.; Xu, G. Recent Advances and Challenges in Hybrid Supercapacitors Based on Metal Oxides Carbons. Inorganics 2025, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wu, T.; Han, Y.; Aryana, S. Fabrication of Mn-Ce Bimetallic Oxides and Electrode Material for Supercapacitors with High Performance. J. Electron. Mater. 2021, 50, 2725–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Rao, R.; Thomas, T. Comparison of the electrochemical performance of CeO2 and rare earth-based mixed mettalic oxide (Ce0.9Zr0.1O2) for supercapacitor applications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Materials, Energy and Environmental Sustainability, Dehradun, India, 14–15 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, G.; Pant, B.; Soo-Jin, P.; Park, M.; Hak-Yong, K. Synthesis and characterization of reduced graphene oxide decorated with CeO2-doped MnO2 nanorods for supercapacitor application. J. Coll. Int. Sci. 2017, 494, 338–344. [Google Scholar]

- Yetiman, S.; Pecenek, H.; Dokan, F.K.; Sanduvac, S.; Onses, M.S.; Yilmaz, E.; Sahmetlioglu, E. Unlocking the Potential of Bismuth-Based Materials in Supercapacitor Technology: A Comprehensive Review. Chem. Electro. Chem. 2024, 11, e202300819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Mallows, J.; Adamas, K.; Nichol, G.S.; Thijssen, J.H.J.; Robertson, N. Thiourea Bismuth Iodide: Crystal structure, Characterization and High Performance as an Electrode Material for Supercapacitor. Batter. Supercaps 2019, 2, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, E.G.; Ramulu, B.; Nagajaru, M.; Yu, J.S. Electrochemically triggered rational design of bismuth cooper sulfide for wearable all-sulfide-semi-solid-state supercapacitor with a wide operational potential window (1.8 V) and ultra-long life. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 3270. [Google Scholar]

- Deepi, A.; Srikesh, G.; Nesaraj, A.S. Electrochemical performance of Bi2O3 with decorated graphene nano composites for supercapacitor applications. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 2018, 15, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, Y.; Kuzhandaivel, H.; Nallathambi, K.S.; Elayappan, V. Enhanced Cyclic Satability of Cobalt Doped Bi25FeO40/BiFeO3 as an Electrode Material for a Super Long Life Symmetric Supercapacitor Device. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 8624–8636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanitha, M.; Keerthi; Cao, P.; Balasubramanian, N. Ag nanocrystals anchored CeO2/graphene nanocomposite for enhanced supercapacitor application. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 644, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, B.; Sankapal, B.R.; Koinkar, P.M. Novel chemical route for CeO2/MWCNTs composite towards highly bendable solid-state supercapacitor device. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnan, M.; Priya-Nanda, O.; Durai, L.; Badhulika, S. One-step hydrothermal synthesis of Bi2CuO4 nanoflakes: An excellent electrode material for symmetric supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2023, 63, 106993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Huo, X.; Li, X.; Park, S.; Lin, L.; Yoon Park, S.; Diao, G.; Piao, Y. Nitrogen and Sulfur Codoped Porous Carbon Directly Derived from Potassium Citrate and Thiourea for High-Performance Supercapacitors. Langmuir 2022, 38, 10331–10337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, A.K.; Samant, P.V. Thiourea modulated supercapacitive behavior of reduced graphene oxide. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 145, 111122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gras, M.; Kolanowski, L.; Wojciechowski, J.; Lota, G. Electrochemical supercapacitor thiourea-based aqueous electrolyte. Electrochem. Commun. 2018, 97, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskolkova, O.; Gnatovskaya, V.; Trush, D.; Vylivok, D.; Khomutova, E.; Fershtat, L.; Larin, A. Novel insights into the Structure and Reduction of Graphene Oxide: A Case of Thiourea. Materials 2025, 18, 5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yao, S. Cerium-doped SnS micron flowers with long life and high capacity for hybrid supercapacitors. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 976, 173402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnegowda, J.; Ramesh, A.M.; Gangadhar, A.; Shivanna, S. Hydrothermal processing of interfacial BiCeO3/MWCNTs photocatalyst for rapid dye degradation and its biological interest. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thendral, M.; Mariappan, M.; Selvarajan, G. Synthesis growth and characterization of a new NLO material: Thiourea urea manganese chloride. Int. J. Chem. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 7, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Lin, J.; Li, G.; Li, T.; Wang, D.; Zheng, W. Sulfur atom occupying surface oxygen vacancy to boos the charge transfer and stability for aqueous Bi2O3 electrode. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 11, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, P.; Wang, H.; Lai, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, Q.; Kuo, D.H.; Lu, D.; Mosisa, M.T.; Li, J.; et al. Synergistic Co/S co-doped CeO2 sulfur-oxide catalyst for efficient catalytic reduction of toxic organics and heavy metal pollutants under dark conditions. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 58, 104820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Wu; Kuo, D.H.; Yang, B.; Wu, B.; Chen, L.; Zhang, P.; Lin, J.; Lu, D.; Chen, X. Synergistic vacancy defects and band-gap engineering in a Ag/S co-doped Bi2O3-based sulfur oxide catalyst for efficient hydrogen evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 10494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, Y.; Fauziyah, S.; Nurhayati, S.; Wulansari, A.D.; Andianingrum, R.; Hakim, A.R.; Bhaduri, G. Synthesis of α-Bismuth oxide using solution combustion method and its photocatalytic properties. Mat. Sci. Eng. 2016, 107, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, K.; Du, Y.; Shan, Y.; Duan, P.; Ramzan, N. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Cellulose with Ammonium Sulfate and Thiourea for the Production of Supercapacitor Carbon. Polymers 2023, 15, 4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés, L.; Mendoza, R.; Oliva, A.I.; García, C.R.; Medina-Velázquez, D.Y.; Oliva, J. A sustainable and foldable supercapacitor made with electrodes of recycled soda-label/graphene/ZnO:Ca and its mechanism for the charge storage. J. Energy Storage 2022, 51, 104601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, S.C.; Stöwe, K. Preparation of Cerium-Bismuth Oxide Catalyst for Diesel Soot Oxidation Including Evaluation of an Automated Soot-Catalyst Contact Mode. ChemistryOpen 2022, 11, e202100282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, N.; Ray, S.S. Performance of bismuth-based materials for supercapacitor applications: A review. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 25, 101691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, H.T.; Balaji, E.; Dutta, S.; Das, N.; Das, P.; Mondal, A.; Imran, M. Recent trend of CeO2-based composites electrode in supercapacitor: A review on energy storage applications. J. Energy Storage 2022, 50, 104643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, S.T.; Selvan, R.K.; Ulaganathan, M.; Melo, J.S. Fabrication of Bi2O3||AC asymmetric supercapacitor with redox additive aqueous electrolyte and its improved electrochemical performances. Electrochem. Acta 2014, 115, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Down, M.P.; Rowley-Neale, S.J.; Smith, G.C.; Banks, C.E. Fabrication of graphene oxide supercapacitor devices. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurursamy, L.; Anandan, S.; Liu, N.; Wu, J.J. Synthesis of a novel hybrid anode nanoarchitecture of Bi2O3/porous-RGO nanosheets for high performance asymmetric supercapacitor. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2020, 856, 113489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, D.; Ashiq, F.; Muneer, I.; Fahad, H.M.; Wahhed, A.; Butt, M.Z.; Ahmad, R.; Mohd-Razip-Wee, M.F. Bismuth iron manganese oxide nanocomposite for high performance asymmetric supercapacitor. Electrochem. Acta 2023, 464, 142863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, L.; Guo, R.; Hu, T.; Ma, M. Using thiourea as a catalytic redox-active additive to enhance the performance of pseudocapacitive supercapacitors. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2021, 5, 5733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magar, H.S.; Hassan, R.Y.A.; Mulchandani, A. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Principles, Construction, and Biosensing Applications. Sensors 2021, 21, 6578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Tan, X.; Li, H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, G.; Gue, M. Investigation on pore structure regulation of activated carbon derived from sargassum and its application in supercapacitor. Sci. Rep. Nat. 2022, 12, 10106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, H.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Q.; Sun, H.; Sun, Q.; Wang, B. Revealing the mechanism of oxygen-containing functional groups on the capacitive behavior of activated carbon. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 657, 159744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).