Abstract

This study aimed to synthesize silver nanoparticles using alcoholic extract of spearmint (Mentha spicata) leaves as a reducing agent and to evaluate their antimicrobial properties. Extract concentrations of 2–5% were used in media with varying pHs. Techniques such as UV-vis spectroscopy, FTIR, and DLS were used to characterize the nanoparticles. The formation of silver nanoparticles was verified by the appearance of a plasmon resonance peak at 418 nm with 2% extract and pH 9. DLS analysis showed a size of 16.1 nm for the 2% extract, which decreased to 10.8 nm with increasing concentration. These results demonstrated that alkaline pH and low extract concentrations favor the formation of monodisperse silver nanoparticles, while higher concentrations induce polydispersity. Silver nanoparticles exhibited antimicrobial activity against E. coli, S. aureus (complete inhibition) and C. albicans (inhibition halo), highlighting their potential in biomedical applications.

1. Introduction

Silver nanoparticles (Ag-nps) are widely recognized for their unique properties, which make them very valuable in diverse fields, such as medicine, environmental protection, and electronics, among others [1,2]. In medicine, due to their antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antifungal, antioxidant and anticancer properties, they are exploited to, among other things, determine the administration of drugs and to identify coatings for biomedical products [3,4,5]. In industry, thanks to their bactericidal activity and their low thermal and electrical resistance, they are used in water treatment, environmental remediation and monitoring, food packaging, textiles and other industrial processes [6,7]. Despite all the advantages they present, there is a risk of toxicity influenced by their size, morphology, excessive use, and particularly by the synthesis methods, generating potential risks for the environment and human health [8,9]. They can bioaccumulate in living organisms and disrupt ecosystems by killing beneficial bacteria in soil and water [2,8]. Unlike traditional synthesis methods, green synthesis or nanoparticle biosynthesis uses natural resources such as plant extracts, microorganisms, and biological waste as reducing and stabilizing agents without the need for potentially harmful chemicals [10,11,12], which is advantageous due to the low environmental impact, lower toxicity [13], cost-effectiveness [14], and the ability to produce nanoparticles with increased stability [15,16], with various shapes and sizes, which can influence their biological properties [17,18].

Due to the green and sustainable approach, green synthesis or biosynthesis of Ag-nps has been attracting increasing amounts of attention in recent years, particularly in procedures incorporating plant extracts [19,20]. The process involves the use of aqueous extracts of plant leaves to reduce silver ions to Ag-nps. This suggests that the choice of plant extract and the morphology of the resulting nanoparticles are critical factors in optimizing the biological efficacy of Ag-nps [21,22]. Erci et al. verified that the morphology of silver nanoparticles synthesized using Thymbra spicata L. var. spicata extract depends on the concentration of extract used and that these exhibit shape-dependent biological activities, and that non-spherical nanoparticles showed enhanced antibacterial and cytotoxic effects compared to spherical ones [23]. Hussain et al. used Mentha piperita extract for the fabrication of spherical silver nanoparticles and verified their antimicrobial efficacy against bacteria such as Staphylococcus and E. coli, among others [24]. Also, Kavitha et al. fabricated silver nanoparticles from plant extracts such as Tulsi (Ocimum tenuiflorum), Spearmint (Mentha spicata) and Neem (Azadirachta indica) with a size of 10 nm and verified that they showed effectiveness against fungi and bacteria [25]. On the other hand, Qaeed et al. studied the effect of different concentrations of aqueous extract of Mentha spicata on the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles. The UV-vis spectra of the nanoparticles showed a gradual increase in absorption with an increasing concentration of Mentha spicata aqueous extract solution from 0.25 to 1.00 mM accompanied by a shift in wavelength from 455 to 479 nm, along with a change in nanoparticle size from 31 to 9 nm. The tests also showed increased activity of the particles in response to E. coli bacteria [22]. Similarly, Qaeed et al. examined the effects of varying concentrations of Ocimum basilicum and Mentha spicata aqueous extracts on the synthesis of Ag-nps. As the concentration of Mentha spicata aqueous solution decreased from 0.75 to 0.25 mM, the size of the nanoparticles changed from 73.57 to 89.05 nm and the wavelength shifted from 468 to 474 nm. Experiments revealed that these nanoparticles exhibited significant antibacterial activity against E. coli [20]. On the other hand, Mir-Hassan et al. developed spherical gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) and silver nanoparticles using Mentha spicata L. essential oil and demonstrated their antibacterial, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities in vitro [26]. Similarly, Hashim et al. studied the biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from ethanolic extract of Mentha spicata leaves. With their methodology, they obtained nanoparticles with spherical morphology that showed efficient inhibitory activity against bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Enterococus faecalis, Proteus mirabilis, and Acinetobacter baumannii [21]. Meanwhile, Torres-Martinez et al. used aqueous extract of Mentha spicata leaves to synthesize silver nanoparticles between 15 and 45 nm in diameter, and demonstrated their cytotoxicity and anticancer activity [19].

It is becoming evident that green synthesis methods are crucial for the sustainable advancement of nanotechnology. They minimize the use of hazardous chemicals, reduce energy consumption, and lower production costs, making them suitable for large-scale production [27]. However, despite several reports that have focused on using Mentha spicata for nanoparticle biosynthesis, most studies have focused on either the extract concentration or the type of solvent, without systematically examining how pH conditions interact with concentration to shape nanoparticle size, dispersity, and ultimately their antimicrobial effectiveness. This represents a relevant knowledge gap, since both parameters are known to strongly influence nucleation and growth processes, as well as surface reactivity. Therefore, the aim of this study is to biosynthesize Ag-nps using Mentha spicata leaves extract as a reducing agent and to analyze the effect of extract concentration and pH on their physical and antimicrobial properties. In this way, this work not only extends the current understanding of plant-mediated synthesis but also provides insights into how synthesis conditions can be optimized to enhance the biological performance of silver nanoparticles. This approach represents an innovative contribution toward bridging green nanotechnology and promotes sustainable research in the area of nanomaterials and their applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Spearmint (Mentha spicata) Leaves Extract (HB-E) Preparation

Spearmint (Mentha spicata) leaves were dried and ground into a powder. This powder was suspended in 96% alcohol (Alkofarma, Trujillo, Peru) at a mass-to-volume ratio of 0.5 g/mL. The suspension was subjected to ultrasound for 30 min and then allowed to macerate for 48 h. Finally, the extract was subjected to ultrasound again for 30 min, and the supernatant and solid residues were separated by filtration using a 42/125 mm Whatman filter. The resulting extracts were stored at 4 °C.

2.2. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles

The synthesis process of silver nanoparticles was carried out using the green synthesis or biosynthesis method, in which natural extracts are used as reducing agents and/or stabilizing agents through their bioactive components to replace potentially toxic chemical reagents. In this work, Merck silver nitrate (AgNO3) at a concentration of 1 mM dissolved in distilled water was used as a precursor. This solution was maintained with magnetic stirring at a temperature of 60 °C for 15 min. The previously prepared spearmint extract was added to the silver nitrate solution at concentrations of 2, 3, 4, and 5% v/v. This process was carried out slowly, drop by drop. Subsequently, in order to evaluate the effect of pH, sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was added at 0.01 M, maintaining magnetic stirring at all times. Samples were obtained at pH values of 5, 7, and 9. Successful silver nanoparticles synthesis was first indicated by a change in the color of the solution, usually from pale yellow to reddish brown [22,28]. Finally, the fabricated nanoparticle colloids were stored at 4 °C and isolated from all light sources until further characterization.

2.3. Characterization Techniques

The optical properties of the extract and the colloidal samples of silver nanoparticles were characterized by UV-Vis spectrophotometry (Shimatzu, UV 1900, Tokyo, Japan) at room temperature, analyzing the presence of the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) peak typical of silver nanostructures. In addition, the functional groups were determined by FTIR spectrophotometry (Thermo Fisher Nicolet IS-50, Waltham, MA, USA). The spectrum for each sample was performed with 20 scans in a frequency range from 4000 to 400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1. Furthermore, dynamic light scattering analysis (Entegris, Nicomp Nano Z3000, Billerica, MA, USA) was performed to characterize the size distribution of Ag nanoparticles. On the other hand, antimicrobial activity was evaluated by observing zones of inhibition in cultures of Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Candida albicans. Bacterial colonies were resuspended in sterile physiological saline, and their turbidity was compared with McFarland’s standard solution No. 0.5, corresponding to 1.08 × 108 CFU/mL. Then, 100 µL of each bacterial suspension was inoculated into Petri dishes containing 15 mL of previously poured Mueller–Hinton agar. Subsequently, wells with a diameter of 0.5 cm were aseptically prepared on the already solidified agar. Then, 60 µL of the extract samples was added. After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, the Petri dishes were examined for clear zones around the well, indicating inhibition of microbial growth. The diameter of these inhibition zones was finally measured in three different orientations using a Vernier caliper.

3. Results and Discussion

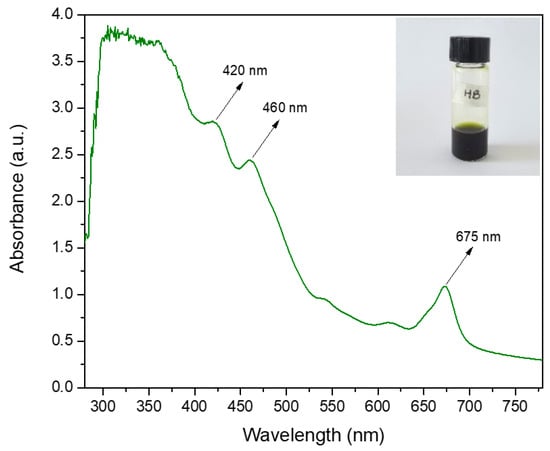

Figure 1 shows the UV-vis spectrum of spearmint extract. The absorbance peaks were mainly observed at 420, 460 and 675 nm, and were characteristic of the photosynthetic pigments chlorophyll a and b found in the leaves of different plants [29,30,31,32]. Chlorophylls a and b are the main pigments involved in light absorption for photosynthesis. These pigments present distinctive absorption peaks in the UV-Vis spectrum, typically around 390–420 nm, 430–460 nm, and 650–680 nm [33]. The peaks located at 420 and 675 nm, which correspond to the violet and red regions, respectively, could be due to the presence of chlorophyll a. In particular, the peak at 675 nm could normally be found around 660–665 nm. Its displacement could be due to the interaction with other compounds and its greater intensity confirms the dominant presence of this compound [34]. The peak located at 460, corresponding to the blue region, would indicate the presence, also, of chlorophyll b. On the other hand, the absorbance in other regions between 300 and 400 nm could be related to other compounds such as anthocyanins and carotenoids [32,35].

Figure 1.

Spearmint (Mentha spicata) extract UV-vis absorbance spectroscopy.

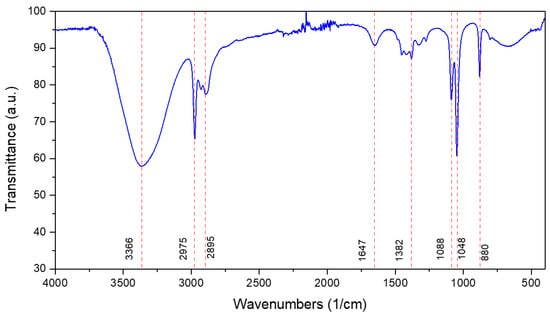

The chemical composition of spearmint extract was identified by FTIR spectroscopy [36]. Figure 2 reveals characteristic absorption bands of functional groups and compounds present in the extract, such as alcohols and alkanes. The most relevant peaks include a band around 3360 cm−1, attributed to O–H groups of phenolic compounds or water; bands between 2975 and 2895 cm−1, associated with C–H bonds, present in compounds such as carvone and limonene [26,37], and C–H2 and C–H3 groups, due to the presence of chlorophyll [38]; and a peak near 1647 cm−1, typical of C=O groups, corresponding to carbonyls in essential oils or acid derivatives [39]. Other peaks were found between 1400 and 800 cm−1, related to C=C and C–O bonds, which are common in plant metabolites [40]. These results are consistent with the chemical composition reported for spearmint, highlighting the presence of chlorophyll, polyphenols, and other active compounds [41].

Figure 2.

Spearmint (Mentha spicata) extract FTIR spectroscopy.

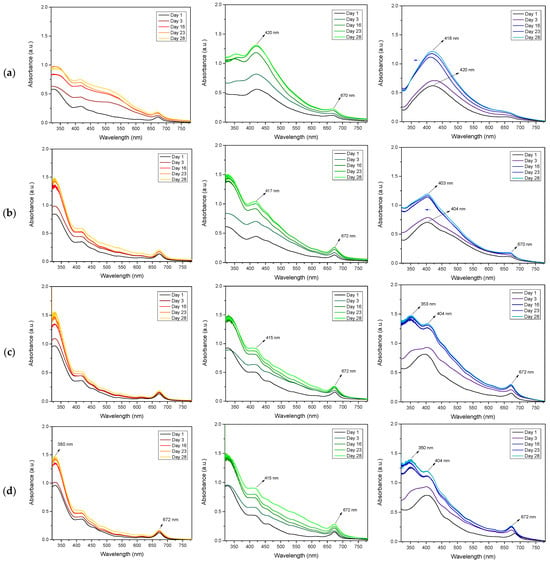

Figure 3 shows the results of UV-vis spectra of Ag-nps synthesized using 2, 3, 4, and 5% spearmint extract and pH of 5, 7, and 9, these were evaluated between the first day and 28 days after synthesis. The formation of Ag-nps was confirmed by the presence of the characteristic surface plasmon resonance (SPR) peak that is typically located at around 400–450 nm in the UV-vis spectrum [21,24,26]. It is observed that, at pH 5, increasing the extract concentration (3–5% HB-E) generated two defined peaks at 380 nm and 672 nm, with the first suggesting the formation of silver atomic clusters or extremely small nano-particles due to accelerated nucleation by excess reducing agents, while the peak at 672 nm indicates aggregation of nanoparticles or non-spherical shapes [42], probably due to colloidal destabilization in acidic medium. At pH 7, a main peak was observed at 420 nm with 2% HB-E, typical of spherical nanoparticles, which decreased in intensity and shifted to 415 nm (4–5% HB-E), reflecting a reduction in particle size due to excess extract, which competes between reduction and stabilization, in addition to the appearance of the peak at 380 nm, which is similar to that observed at pH 5. The case of pH 9 with 2% extract stands out, where the peak at 418 nm showed the formation of highly stable Ag-nps. However, as the concentration increased (4–5% HB-E), this peak shifted to 404 nm, indicating smaller particles. A shoulder also appeared at 350 nm, possibly due to non-reducing compounds in the extract, and a peak at 672 nm (aggregates). This indicates that excess extract in an alkaline medium favors the formation of Ag-nps, but could also reduce efficiency. On the other hand, the minimal differences between days 23 and 28 show overall stability over time, confirming that the Ag-nps reach colloidal equilibrium, although optimal monodispersity is only achieved at pH 7–9 and 2% extract, while higher concentrations (4–5%) generate complex systems with interference from the extract components.

Figure 3.

UV-vis spectra of Ag-nps fabricated using row (a) 2%, row (b) 3%, row (c) 4%, and row (d) 5% of HB-E. It also shows the variation in pH: Red for pH 5, Green for pH 7, and Blue for pH 9.

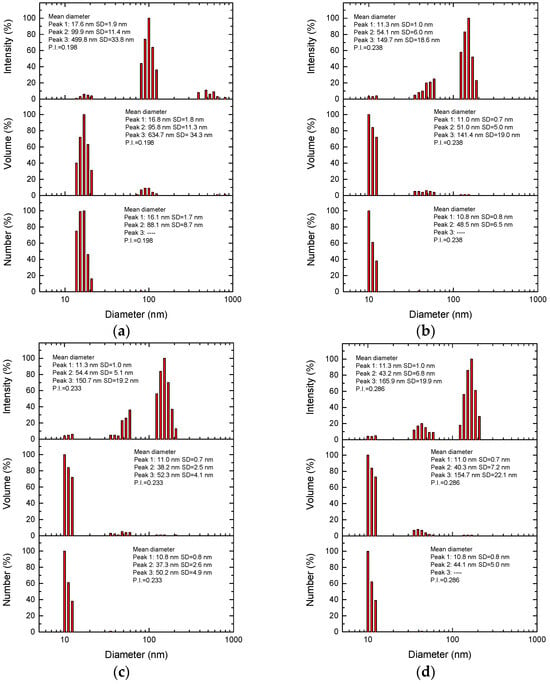

A DLS analysis of Ag-nps biosynthesized with spearmint extract at different concentrations and pH 9 is shown in Figure 4. The number-wise results show that as the extract concentration increased from 2% to 5%, the average nanoparticle size decreased from 16.1 nm (2%) to 10.8 nm (3–5%), while the polydispersity index (P.I.) slightly increased from 0.198 (2%) to 0.286 (5%), indicating that higher extract concentrations favor the formation of smaller nanoparticles, but with less homogeneous size distribution. This trend is in agreement with the UV-Vis results, where the shift in the SPR peak from 418 nm (2%) to 404 nm (5%) reflects a reduction in particle size, a typical phenomenon in silver nanoparticles when the SPR is shifted towards shorter wavelengths [43]. The progressive increase in P.I. (especially at 5%) also correlates with the appearance of secondary peaks in UV-Vis (672 nm and 350 nm), suggesting that excess extract promotes not only small particles (10.8 nm) but also the formation of aggregates and/or interference from residual organic compounds [19,21]. The sample with 2% HB-E showed the best balance between size (16.1 nm) and uniformity (P.I. = 0.198), consistent with its well-defined UV-Vis spectrum (418 nm) and stability over time, while higher concentrations (3–5%), despite producing smaller nanoparticles, introduced greater polydispersity.

Figure 4.

Mean diameter by DLS of Ag nps fabricated using (a) 2%, (b) 3%, (c) 4% and (d) 5% of HB-E. All samples reach pH 9.

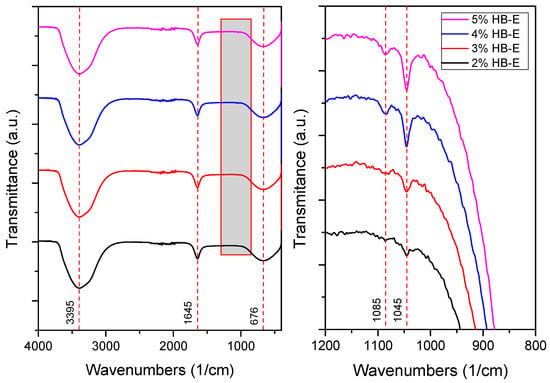

Figure 5 shows the FTIR spectra of Ag-nps synthesized with spearmint extract at different concentrations. Three main peaks are observed—one at 3395 cm−1, attributed to OH groups (such as alcohols, phenols or adsorbed water); another at 1645 cm−1, associated with C=O (carbonyl) or C=C (alkene) bond vibrations present in the organic compounds of the extract [38,40]; and a third at 676 cm−1, which is possibly related to Ag-O vibrations. A comparison of the FTIR spectrum of silver nanoparticles (Figure 5) with that of spearmint extract (Figure 2) reveals the absence of some peaks containing bands such as C–H, C≡C, and C–O associated with functional groups such as polyphenols and flavonoids present in Mentha spicata extract, indicating their participation in the synthesis of silver nanoparticles, responsible for the reduction and stabilization [22,26]. In the broadened region (1200–800 cm−1), the peak at 1045 cm−1, whose intensity increases with the concentration of HB-E, can be assigned to vibrations of C–O bonds (ethers, secondary alcohols or polysaccharides) or C-N groups (amines), present in the extract, confirming the presence of organic residues adsorbed on the nanoparticles. These findings correlate with UV-vis and DLS analyses, where a 2% concentration of HB-E produced nanoparticles of 16.1 nm with a defined plasmon peak at 418 nm, whereas higher concentrations generated smaller particles (~11 nm) but with less defined UV-vis spectra, likely due to excess organic compounds affecting dispersion and colloidal stability. This suggests that although higher extract concentrations reduce the size, they may compromise the optical quality of the nanoparticles, highlighting the need to optimize the extract ratio to balance size, functionality, and optical properties [26].

Figure 5.

FTIR spectroscopy of fabricated Ag nanoparticles.

The antimicrobial properties of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using 2–5% HB-E at pH 9 were evaluated against S. aureus, E. coli, and C. albicans by measuring the inhibition halo and the results are shown in Table 1. Regarding the antimicrobial effect against Gram-positive bacteria such as S. aureus, bacterial growth was observed when using 2% HB-E, indicating that the concentration used for this synthesis was not sufficient to generate nanoparticles capable of inhibiting these bacteria. Meanwhile, growth inhibition was observed at concentrations of 3–5% HB-E, demonstrating that higher concentrations of the extract used in the synthesis increase the antimicrobial efficacy. Against Gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli, complete and uniform growth inhibition was observed even at low extract concentrations. This sensitivity suggests a consistent mechanism of action for all concentrations. Differences in the cell wall structure of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria could explain why the manufactured nanoparticles are more effective against E. coli than S. aureus [6,21,24,44]. Regarding its efficacy against C. albicans, the formation of inhibition halos is observed; the effect of the nanoparticles containing 2% HB-E on the fungus is notable, creating an inhibition area of 8.8 mm in diameter. At higher concentrations (and smaller particle size), this antifungal effect varies; although the diameter is reduced, there is no exact correlation between the extract concentration and the halo diameter. However, the size of the nanoparticles could affect the release of silver ions against microorganisms such as C. albicans.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial analysis of Ag nanoparticles on S. aureus and E. coli bacteria, and C. albicans fungi.

4. Conclusions

In this study, silver nanoparticles were biosynthesized using spearmint (Mentha spicata) leaves extract as a reducing agent, and their formation was evaluated using concentrations of 2, 3, 4, and 5% at pH 5, 7, and 9. The results highlight that, at pH 9, a 2% extract concentration is optimal for obtaining silver nanoparticles with controlled size and low dispersity. Higher concentrations generated interference (350 nm) and polydispersity (404 nm and 672 nm). DLS analysis found an average size of 16.1 nm (2%), which decreases with increasing concentration. On the other hand, silver nanoparticles biosynthesized with spearmint extract were shown to be effective against E. coli and S. aureus bacteria, showing inhibition. The effect of the nanoparticles on the fungus is notable, with the formation of an inhibition halo of up to 8.8 mm in diameter. These results imply that controlling the physical properties of green-synthesized silver nanoparticles, optimizing the extract/silver ratio and pH to control the size and stability of the nanoparticles, can improve their efficacy as antimicrobial agents. A low dispersion is relevant because particle uniformity is directly related to their biological performance. Although the antimicrobial results are promising, further studies are still required to optimize their applications in medicine or industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R.N.-N. and M.M.G.-C.; methodology, R.R.N.-N. and M.M.G.-C.; software, M.M.G.-C.; validation, R.R.N.-N., L.M.A.-S. and S.M.B.; formal analysis, R.R.N.-N. and M.M.G.-C.; investigation, N.A.T.-R. and L.M.A.-S.; data curation, L.M.A.-S. and N.A.T.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R.N.-N.; writing—review and editing, S.M.B. and M.M.G.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Dirección de Investigación of Universidad Autónoma del Perú.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Islam, A.; Jacob, M.V.; Antunes, E. A critical review on silver nanoparticles: From synthesis and applications to its mitigation through low-cost adsorption by biochar. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 281, 111918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofi, M.A.; Sunitha, S.; Sofi, M.A.; Pasha, S.K.; Choi, D. An overview of antimicrobial and anticancer potential of silver nanoparticles. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2022, 34, 101791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, P.; Jha, S.; Ramteke, S.; Jain, N.K. Pharmaceutical aspects of silver nanoparticles. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.R.; Singh, S.K.; Singh, M. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Methods, biological applications, delivery and toxicity. Mater. Adv. 2023, 4, 1831–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahuman, H.B.H.; Dhandapani, R.; Narayanan, S.; Palanivel, V.; Paramasivam, R.; Subbarayalu, R.; Thangavelu, S.; Muthupandian, S. Medicinal plants mediated the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their biomedical applications. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 16, 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayo, G.M.; Elimbinzi, E.; Shao, G.N. Preparation methods, applications, toxicity and mechanisms of silver nanoparticles as bactericidal agent and superiority of green synthesis method. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandupatla, R.; Shaik, H.; Baswa, A.K.; Prashanth, K.; Manohar, K.; Madhu, M.; Vijaykumar, T. A review on green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles: Advancements and applications in sustainable technology. Rasayan J. Chem. 2024, 17, 1766–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, R.; Seabra, A.B.; Durán, N. Silver nanoparticles: A brief review of cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of chemically and biogenically synthesized nanoparticles. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2012, 32, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamuna, B.A.; Rai, V.R. Environmental risk, human health, and toxic effects of nanoparticles. In Nanomaterials for Environmental Protection; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 523–535. [Google Scholar]

- Asmat-Campos, D.; Abreu, A.C.; Romero-Cano, M.S.; Urquiaga-Zavaleta, J.; Contreras-Cáceres, R.; Delfín-Narciso, D.; Juárez-Cortijo, L.; Nazario-Naveda, R.; Rengifo-Penadillos, R.; Fernández, I. Unraveling the active biomolecules responsible for the sustainable synthesis of nanoscale silver particles through nuclear magnetic resonance metabolomics. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 17816–17827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaie, M.; Ghasemi, N. Green synthesis and characterization of copper nanoparticles using Eryngium campestre leaf extract. Bulg. Chem. Comm. 2018, 50, 244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Burlibaşa, B.; Chifiriuc, M.C.; Lungu, M.V.; Lungulescu, E.M.; Mitrea, S.; Sbarcea, G.; Popa, M.; Măruţescu, L.; Constantin, N.; Bleotu, C.; et al. Synthesis, physico-chemical characterization, antimicrobial activity and toxicological features of AgZnO nanoparticles. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 4180–4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathanmohun, M.; Sagadevan, S.; Rahman, Z.; Lett, J.; Fatimah, I.; Moharana, S.; Garg, S.; Al-Anber, M.A. Unveiling sustainable, greener synthesis strategies and multifaceted applications of copper oxide nanoparticles. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1305, 137788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelere, I.A.; Lateef, A. A novel approach to the green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles: The use of agro-wastes, enzymes, and pigments. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2016, 5, 567–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlacu, E.; Tanase, C.; Coman, N.A.; Berta, L. A review of bark-extract-mediated green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles and their applications. Molecules 2019, 24, 4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, K.; Dhanjal, D.S.; Sharma, A.; Nepovimova, E.; Kalia, A.; Thakur, S.; Bhardwaj, S.; Chopra, C.; Singh, R.; Verma, R.; et al. Conifer-Derived Metallic Nanoparticles: Green Synthesis and Biological Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Matsubara, S.; Xiong, L.; Hayakawa, T.; Nogami, M. Solvothermal synthesis of multiple shapes of silver nanoparticles and their SERS properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 9095–9104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannotti, M.; Rossi, A.; Giovannetti, R. SERS Activity of Silver Nanosphere, Triangular Nanoplates, Hexagonal Nanoplates and Quasi-Spherical Nanoparticles: Effect of Shape and Morphology. Coatings 2020, 10, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Martínez, Y.; Arredondo-Espinoza, E.; Puente, C.; González-Santiago, O.; Pineda-Aguilar, N.; Balderas-Rentería, I.; López, I.; Ramírez-Cabrera, M.A. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using a Mentha spicata extract and evaluation of its anticancer and cytotoxic activity. PeerJ 2019, 7, e8142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qaeed, M.A. Examining the varied concentrations of Mentha spicata and Ocimum basilicum affect the synthesis of AgNPs that restrict the development of bacteria. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 31, 103899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, N.; Bashi, A.M.; Jasim, A. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by Mentha spicata ethanolic leaves extract and investigation the antibacterial activity. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2144, 040009. [Google Scholar]

- Qaeed, M.A.; Hendi, A.; Thahe, A.A.; Al-Maaqar, S.M.; Osman, A.M.; Ismail, A.; Mindil, A.; Eid, A.A.; Aqlan, F.; Al-Nahari, E.G.; et al. Effect of different ratios of Mentha spicata aqueous solution based on a biosolvent on the synthesis of agnps for inhibiting bacteria. J. Nanomater. 2023, 2023, 3599501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erci, F.; Cakir-Koc, R.; Isildak, I. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Thymbra spicata L. var. spicata (zahter) aqueous leaf extract and evaluation of their morphology-dependent antibacterial and cytotoxic activity. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, Z.; Jahangeer, M.; Sarwar, A.; Ullah, N.; Aziz, T.; Alharbi, M.; Alshammari, A.; Alasmari, A.F. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles mediated by the Mentha piperita leaves extract and exploration of its antimicrobial activities. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2023, 68, 5865–5870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, A.; Shanmugan, S.; Awuchi, C.G.; Kanagaraj, C.; Ravichandran, S. Synthesis and enhanced antibacterial using plant extracts with silver nanoparticles: Therapeutic application. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2021, 134, 109045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavy, M.H.; de la Guardia, M.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; Khatibi, S.A.; Hosseinzadeh, N.; Hajipour, N. Green synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation of gold and silver nanoparticles using Mentha spicata essential oil. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodevska, T.; Hadzhiev, D.; Shterev, I.; Lazarova, Y. Application of biosynthesized metal nanoparticles in electrochemical sensors. J. Serbian Chem. Soc. 2022, 87, 401–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasaee, I.; Ghannadnia, M.; Baghshahi, S. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaf extract of Satureja hortensis treated with NaCl and its antibacterial properties. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018, 264, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragán, R.C.; Strojnik, M.; Rodríguez-Rivas, A.; Torales, G.G.; González, F.J. Optical spectral characterization of leaves for Quercus Resinosa and Magnolifolia species in two senescent states. In Proceedings of the SPIE Optical Engineering + Applications, San Diego, CA, USA, 19–23 August 2018; p. 1076511. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.; Buraidah, M.H.; Teo, L.P.; Careem, M.A.; Arof, A.K. Dye-sensitized solar cells with sequentially deposited anthocyanin and chlorophyll dye as sensitizers. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2016, 48, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golshan, M.; Osfouri, S.; Azin, R.; Jalali, T.; Moheimani, N.R. Co-sensitization of natural and low-cost dyes for efficient panchromatic light-harvesting using dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2021, 417, 113345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cari, C.; Khairuddin; Septiawan, T.Y.; Suciatmoko, P.M.; Kurniawan, D.; Supriyanto, A. The preparation of natural dye for dye-sensitized solar cell (DSSC). AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 2014, 020106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Feng, H.; Jin, S.; Gao, J. The research of lamp for the growing of green plants. In Proceedings of the SPIE—The International Society for Optical Engineering, St. Etienne, France, 30 September–3 October; pp. 192–197.

- Calogero, G.; Bartolotta, A.; Di Marco, G.; Di Carlo, A.; Bonaccorso, F. Vegetable-based dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 3244–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patni, N.; Pillai, S.G.; Sharma, P. Effect of using betalain, anthocyanin and chlorophyll dyes together as a sensitizer on enhancing the efficiency of dye-sensitized solar cell. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 10846–10859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunaciu, A.A.; Aboul-Enein, H.Y.; Fleschin, S. Recent applications of fourier transform infrared spectrophotometry in herbal medicine analysis. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2011, 46, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasti, F.; Yousefpoor, Y.; Abdollahi, A.; Safari, M.; Roozitalab, G.; Osanloo, M. Antioxidative, anticancer, and antibacterial activities of a nanogel containing Mentha spicata L. essential oil and electrospun nanofibers of polycaprolactone-hydroxypropyl methylcellulose. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, J.; Oba, O.A.; Aydinlik, N.P. Preliminary phytochemical screening, Gc-Ms, Ftir analysis of ethanolic extracts of Rosmarinus Officinalis, Coriandrum sativum L. and Mentha spicata. Hacet. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 51, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.K.; Soni, A.; Jain, P.; Bhawsar, J. Phytochemical analysis of Mentha spicata plant extract using UV-VIS, FTIR and GC/MS technique. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2016, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Taylan, O.; Cebi, N.; Sagdic, O. Rapid screening of Mentha spicata essential oil and L-menthol in Mentha piperita essential oil by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy coupled with multivariate analyses. Foods 2021, 10, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivalingam, A.M. Biosynthesis of ZnO nanocomposites from Mentha spicata applications of antioxidant, antimicrobial and genotoxicity advances in MCF-7 cell line. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 2024, 46, 100707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Johnston, R.L. Plasmonic properties of silver nanoparticles on two substrates. Plasmonics 2009, 4, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, I.; Zhou, Y. Impact of pH on the stability, dissolution and aggregation kinetics of silver nanoparticles. Chemosphere 2019, 216, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepahvand, P.; Khorramabadi, M.K.; Dousti, B. Investigation of Mechanical and Antibacterial Properties of Starch Nanobiocomposite Film Reinforced with Silver Nanoparticles and Salvia Extract. Int. J. Biomater. 2024, 2024, 4620159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).