Abstract

Nanotechnology is reshaping the built environment by enabling the development of materials that improve structural performance, energy efficiency, durability, and environmental quality. This paper reviews nano-enabled construction materials through a micro–meso–macro lens, linking material mechanisms to building behavior and urban impacts. It highlights both their potential contributions to decarbonization, public health, and urban resilience, and the parallel challenges of energy-intensive production, uncertain toxicological profiles, and regulatory gaps. Finally, it argues for responsible integration based on life-cycle thinking, precautionary risk governance, and updated architectural and engineering education so that nano-enabled innovation supports truly sustainable, equitable cities rather than new forms of hidden risk.

1. Introduction

The building industry is rapidly moving towards zero-carbon, resilient, and environmentally sustainable built environments [1,2], where green nanotechnology is playing a vital role in the reduction in the environmental impact. Globally, buildings contribute to 39.65% of the energy-related CO2 emissions [1]. Out of this, operational use accounts for 28% and embodied carbon in construction materials and processes for 11% [3,4]. In such a scenario, nanomaterials (NPs) provide a huge potential. They improve thermal performance, mechanical strength, and moisture resistance; at the same time, they also give additional advantages such as self-cleaning, energy-saving, and indoor air-purifying functions [5]. Their antimicrobial, antiviral, antibacterial, and antifungal properties thus help in further improving indoor environmental quality [6]. The works of Ben Ghida et al. [2], Ben Ghida [5], Lee et al. [6], Mohajerani et al. [7], Pacheco-Torgal and Jalali [8], and Olafusi et al. [9] brought to light that nanostructured coatings, self-cleaning technologies, and intelligent surfaces are the main innovations that lead to energy saving and the prolongation of the building lifespan.

Besides performance, the emergence of smart and nano-materials is thinning the conventional divide between architecture and materials science. Smart materials are capable of sensing and reacting to stimuli, whereas NPs are at the molecular level, thus affording them ground-breaking self-assembly and material efficiency. Their amalgamation is a signal of the transformative change; buildings of the future may not be mere passive structures, but rather they might become active, high-performance systems, combining architectural design with material intelligence [2,5].

The objectives of this research are as follows:

- Summarize recent advances in construction-related nanotechnologies for professionals and academics;

- Identify research gaps and limitations;

- Recommend actions to support the adoption of nanotechnologies in construction.

This paper uses a targeted literature review to link nano-scale material behavior with building and urban performance. Publications from 2000 onwards were screened, and for each nanomaterial, the type and integration mode, key mechanisms, material- and building-scale effects, and major environmental or adoption issues were recorded. These data are synthesized in a micro–meso–macro matrix that structures the results and supports the final recommendations.

2. Results

NPs are organized in Table 1 along with the micro- (material), meso- (building system), and macro (urban)-scales, and are also categorized by the mechanism, benefit, and application. It reveals how nanoscale properties lead to sustainability outcomes of the urban environment. Through the connection of material innovation with urban goals, the table serves as the initial framework for the discussion of the routes towards resilient and regenerative cities.

Table 1.

Micro–meso–macro matrix of nano-enabled materials in the built environment [2,5].

3. Discussion

3.1. Nanomaterials in Architectural Façades

NP-based coatings and composites implemented on the built envelopes contribute to the heat, weather-resistance, and air quality functions of the buildup [2,5]. Real-world studies show that energy use can be cut by as much as 45% when nano-insulating layers and reflective coatings are applied to the roofs, the walls, and the glazing systems [2,5]. Metal oxide nanoparticles (MONPs) are very efficient at blocking infrared and ultraviolet radiation while at the same time keeping the transparency of the material, thus giving an added advantage of less energy required for cooling and at the same time providing a comfortable environment inside a building [2,5]. The use of reflective nanocoating diminishes the concern of the urban heat island effect in the sense that the surface heating as a result of radiation is reduced [5].

From the point of material conservation, NP methods improve the mechanical basis, water repellency, and resistance to weathering of a material [2,5]. Silicon dioxide (SiO2NPs) treatment products are able to create water-repellent layers on the surface, which at the same time are permeable to vapor and prevent the water introduced through capillary action while the optical characteristics remain unaltered [2,5]. Calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2NPs) and calcium carbonate (CaCO3NPs) nano-powders penetrate deeply into the porous structures, micro-voids are filled, and crystallization processes are activated in situ, which not only hardens the mineral substrates but also increases their compressive strength [2,5].

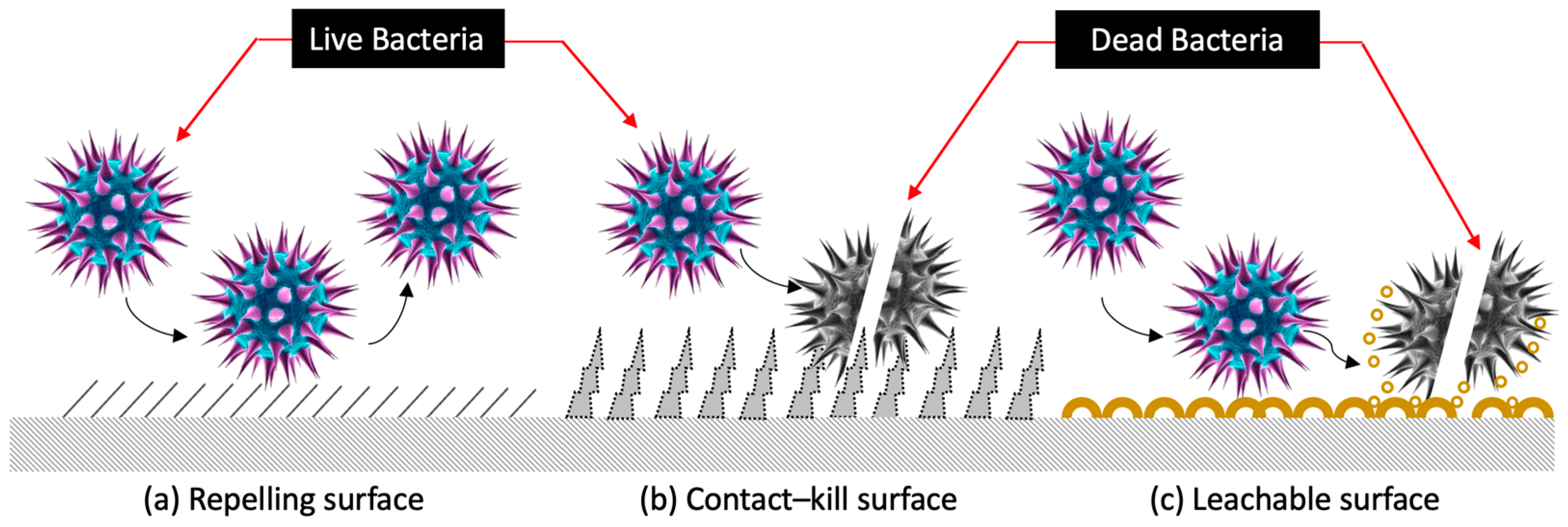

Titanium dioxide (TiO2NPs) nanoparticles have photocatalytic properties that are activated only under light exposure, and they can decompose volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and nitrogen oxides (NOx), thus decreasing the concentration of urban pollutants may be regarded as environmentally friendly [2,5]. Moreover, the superhydrophobic nature of their surfaces renders them self-cleaning, thus diminishing the cleaning cycles and consequently the wear and tear of the surface. Silver (AgNPs) and other metal NPs are capable of exhibiting certain characteristics like antimicrobial and antiviral properties [2,5], shown in Figure 1, which make façades in high-density or public-use environments safer. Besides this, nanostructured anti-graffiti coatings play the role of providing passive protection layers that allow the water-based removal of contaminants from their surfaces without the degradation of the substrate [5].

Figure 1.

Types of antibacterial nano-treated surfaces. (a) Repelling: engineered surface textures limit cell attachment and deflect particles before adhesion. (b) Contact-kill: embedded antimicrobial coatings or micro-spikes deactivate organisms instantly on impact or touch. (c) Leachable: surface-stored antimicrobial agents release outward, creating a protective diffusion zone that suppresses microbial survival.

NP-based paints and coatings can extend the exterior service life of a house by up to twenty years, and this is as a result of the long-term protection that they offer against UV radiation, oxidation, and particulate deposition [5]. This not only enhances the thermal and mechanical performance of the material but also corresponds to present-day sustainability norms by lessening the material’s wear and tear, maintenance, and life-cycle energy consumption.

3.2. Nano-Enabled Cities

NPs are turning into pivotal elements that are changing the face of cities. They are even making cities more eco-friendly, livable, and sustainable on a global scale through the socio-cultural aspect [10,11,12,13]. Urban ecosystems progressively benefit from their incorporation, as it alters approaches to urban planning and local administration, which in turn attracts environmentalist-minded urban dwellers, a pattern that is taking place all over the world in the cities that seek to be healthier and more resistant to changes like droughts and floods that plague the Earth [10,12,13].

Culturally and esthetically speaking, NPs help a city to become more attractive and vibrant through making its identity more durable and cleaner through the preservation of its heritage structures and urban landscape [11,14]. To be precise, these materials offer a new, more effective way to restore architectural heritage and ancient monuments [15,16]. In this light, photocatalytic nano-coatings turn pollutant accumulation into temporary deposits, slow the surface degradation processes, and provide very long-lasting UV protection; this is all very important for the conservation of the primary materials and the minute decorative elements on which the cultural and touristic value of a city largely depend [11]. With the use of nanoparticle technology as a base, anti-graffiti coatings allow soiled surfaces to be washed with water, which not only helps to lessen the frequency of this task and its expenses more and more but also makes it possible for the esthetic quality of clean public spaces to be kept, which is at the same time a prerequisite of local pride and international tourism [14].

To make a measurable difference in nature and the environment in cities, nanotechnology is going to improve urban air quality, resource efficiency, and infrastructural endurance. Photocatalytic NPs, namely TiO2NPs, are implemented on pavements, façades, and other urban structures, making the area pollutant-free by decomposing pollutants and airborne microorganisms; hence, the air becomes much cleaner, and simultaneously, many urban diseases resulting from exposure to polluted air in tightly populated areas are mitigated [10]. By using heat-reflective nanocoating on city buildings and street surfaces, not only is the urban heat island effect lessened, but at the same time, there is a great saving in cooling energy, and the unpleasantness of hot outdoor air on the warmest days is alleviated [17]. The use of antimicrobial and antiviral agents in public areas, such as transit hubs, educational campuses, tourism facilities, and healthcare centers, has become the norm, with their widespread installation being mainly due to the COVID-19 pandemic and other public health needs [11]. The embracing of nano-air-filtration and surface maintenance methods for health and wellness purposes by public sectors and attractions, resulting in the upholding of visitor trust and the general well-being of the urban environment, is reported in cities across different continents [14].

Equally, they represent the core of urban infrastructure longevity, supported via nanomaterial-enabled solutions. Superhydrophobic surfaces [17] help save water, eliminate the need for chemicals, and prevent excessive building maintenance, whereas next-generation materials protect the beauty of the past and ensure that a wide range of transportation infrastructures, old bridges, or public monuments are kept rust-free and with longer service lives, which may in turn result in the cities having a sustainably low frequency of repairs and long-life-cycle costs, and also being moderate consumers of resources. These factors are at the very heart of urban competitiveness, environmental responsibility, and the attractiveness of cities as places to live, work, and visit in the longer term [10,11,17].

Therefore, together with the boosting of technical and environmental performances in different urban fields of activity, NPs are becoming a kind of interwoven thread in the fabric of the world’s most progressive cities; thus, they are catalyzing the transitions to cleaner air, more attractive landmarks, increased tourism potential, healthier public spaces, and lasting sustainability.

3.3. Health and Environmental Risks of Nanomaterials

Recent studies emphasize that the proliferation of engineered nanomaterials (ENMs) introduces a complex spectrum of potential environmental and long-term health hazards, calling for stronger risk governance and adaptive regulatory frameworks [18,19,20,21]. Exposure pathways occur throughout the entire lifecycle of ENMs, from synthesis and application to final disposal, with occupational environments and downstream ecosystems identified as critical points of concern [21]. The defining toxicological feature of these materials is their nanoscale size, which permits translocation across physiological barriers such as the alveolar–capillary interface, intestinal epithelium, and placental membrane, facilitating systemic bioaccumulation [18,19].

Mechanistic evidence indicates that mitochondria are central targets of ENM-induced toxicity. Metal and metal oxide NPs, particularly AgNPs, ZnONPs, and TiO2NPs, can disrupt mitochondrial integrity and function, initiating oxidative stress and cellular injury [19]. This process generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage lipids, proteins, and DNA, promote ferroptosis and inflammation, and increase risk for genotoxicity and carcinogenesis [20]. These oxidative and molecular stress responses appear to underpin many of the adverse outcomes linked to chronic or sub-lethal nanoparticle exposure [19,20].

Recent reviews further suggest that ENMs can act as endocrine-disrupting agents by altering hormonal signaling, particularly thyroid and estrogenic pathways, leading to potential reproductive or metabolic dysfunctions [2,19]. Inhalation remains one of the most significant exposure routes. Studies of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and amorphous silica document their persistence within lung tissue, where they can induce fiber-like pathologies characterized by inflammation, granuloma formation, and fibrotic remodeling similar to asbestos-related lesions [20,21].

Environmental research demonstrates that ENMs are disseminated via effluent release, atmospheric deposition, and biosolid application, leading to accumulation in aquatic and terrestrial systems [18,21]. In aquatic settings, ENMs tend to agglomerate or integrate into biological tissues, contributing to oxidative injury, reduced reproduction, and growth inhibition in algae, crustaceans, and fish [20]. In soils, nanoparticles disrupt microbial communities essential for biogeochemical cycling, degrading soil fertility and ecological resilience [18]. Contemporary environmental models increasingly highlight the cumulative and chronic impacts of low-dose exposure, as well as the reactivity and long-term transformations that ENMs undergo as they interact with environmental media [21].

In light of these converging findings, experts recommend applying a precautionary approach based on recent interdisciplinary evidence. Strengthened protocols for toxicological screening, incorporating “omics” and high-throughput assays, combined with multilayered occupational protections and lifecycle-oriented regulations, are now regarded as essential for ensuring both the safety and sustainability of NPs [20,21].

3.4. Barriers and Pathways for Nanotechnology Adoption in Construction

Environmental, economic, and regulatory challenges limit the use of nanotechnologies in the building industry. Despite their efficiency, the expansive application of nanotechnologies is stalled by several research gaps that seriously restrict their implementation [2,5]. One of the major issues that most industries and scientific papers agree on is the high manufacturing cost of NPs [2,5,17]. Common energy-consuming methods for the production of NPs, namely sol–gel, chemical vapor deposition, and hydrothermal processes, use hazardous reagents and have limited scalability [2,5]. The mentioned drawbacks altogether increase the environmental impacts of nanomanufacturing and thus are in direct contradiction with the sustainability principles toward which the construction industry wants to move [2,5,17].

Another big hurdle comes from the lack of sufficient knowledge of the long-term behavior of NPs in the construction of the environment. The strength, durability, or even self-cleaning properties of materials at the nano-level have been demonstrated by various studies [2,5,8]; however, the degradation of lifecycle, the release of NPs, and the recyclability of nano-enhanced composites after the service are not well understood [2,5,17,21]. Besides the technical issues, there are concerns about the health of workers and the environment as well. Some nanoparticles show toxicological behaviors that are very similar to those of asbestos fibers; for example, fiber-shaped carbon nanotubes have been reported to cause pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis through the same processes [2,20,21]. The absence of standardized measurement methods, safety testing procedures, and regulatory frameworks for nanoparticles is still the main reason for slow industrial uptake [17].

Three strategic priorities are recommended by recent articles to speed up the adoption of nanotechnology:

- The first one is the requirement for more interdisciplinary collaboration among engineers, material chemists, toxicologists, and policymakers for the creation of the safety standards with international validity and the supportable certification procedures [2,5,21,22].

- The second point of cost challenges should be resolved by technological innovations [23]. The problems with production cost and circular economy compliance will be solved by the large-scale, environmentally friendly production methods based on green synthesis, bio-templating, and continuous processes in the reactor [2,5]. In addition, leading-edge manufacturing methods, such as modular hybrid plasma reactors (MHPRs) and organic solvent-free synthesis, are rapidly gaining popularity as effective routes to scalable mass production [18,24].

- The third point worthy of attention is academic education and professional training [15,22,25,26,27]. The introduction of nanotechnologies and materials-science topics to architecture curricula will be instrumental in overcoming the deficiency of the experts who can assess the performance, risk, and regulation aspects [17,24].

Once the industry has solved this trio of problems—expensive production, unclarified safety issues, and lack of personnel—nanotechnology will be able to make a qualitative leap from experimental applications to the standard, economically viable tools that not only help to realize sustainable construction but also smart-city infrastructure [28,29,30].

4. Conclusions

Nanotechnology is adding a new material dimension to architecture and construction. At the micro-scale, SiO2NPs, Al2O3NPs, nanoclays, CNTs, and graphene derivatives modify the hydration of C3S and C2S and the formation of C–S–H gel, refining pore structure, reducing Ca(OH)2, and bridging microcracks. This improves compressive strength and lowers permeability in concrete and mortars.

Photocatalytic TiO2NPs coatings change the chemistry of the building’s exterior, oxidizing NOx and VOCs and limiting biofilm growth. Aerogels and nano-porous insulators reduce effective λ (thermal conductivity), while nano-enhanced PCMs increase usable latent heat (ΔH_fus) in envelopes and components, smoothing indoor temperature swings and peak loads.

At the building and urban scales, these mechanisms can reduce operational energy, extend service life, cut maintenance, and support cleaner, more comfortable environments. Properly specified, nano-enabled systems can contribute to decarbonization, heat-island mitigation, and urban resilience.

However, the same features that make engineered nanomaterials effective—sizes typically <100 nm, high specific surface area and reactivity—also drive concerns regarding inhalation, bioaccumulation, and environmental persistence. Current building standards rarely address nano-specific hazards or end-of-life scenarios.

The key issue is not whether nanotechnology will permeate the built environment, but under what technical and governance conditions. Progress requires cleaner synthesis routes, life-cycle assessments that account for nano-scale properties, and adaptive regulation. For architects, engineers, planners, and educators, nanotechnology must be treated as a design parameter that affects envelope performance, maintenance strategies, urban metabolism, and public health. Integrated deliberately and responsibly, nano-enabled materials can be allies in building sustainable, resilient cities; if mishandled, they risk becoming the next generation of environmental and health liabilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B. and S.B. (Sonia BenGhida); methodology, S.B. (Sonia BenGhida); validation, D.B., R.B. and S.B. (Sabrina BenGhida); formal analysis, S.B. (Sabrina BenGhida); investigation, S.B. (Sonia BenGhida); resources, S.B. (Sabrina BenGhida); data curation, S.B. (Sabrina BenGhida); writing—original draft preparation, D.B.; writing—review and editing, R.B.; supervision, D.B.; project administration, R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ben Ghida, D. CO2 Reduction from Cement Industry. In Proceedings of the AMMSE 2015, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 18–20 September 2015; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Pisini, S.K.; Thammadi, S.P.; Wilkinson, S. Energy-efficient buildings for sustainable development. In Sustainable Civil Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. Global CO2 Emissions from Buildings, Including Embodied Emissions from New Construction 2022; IEA: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/global-co2-emissions-from-buildings-including-embodied-emissions-from-new-construction-2022 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- World Green Building Council. Bringing Embodied Carbon Upfront. World Green Building Council. 2019. Available online: https://worldgbc.org/advancing-net-zero/embodied-carbon/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Ben Ghida, D. Nanomaterials’ Application in Architectural Façades in Italy. Appl. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2022, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Mahendra, S.; Alvarez, P.J. Nanomaterials in the Construction Industry: A Review of Their Applications and Environmental Health and Safety Considerations. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 3580–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, A.; Burnett, L.; Smith, J.V.; Kurmus, H.; Milas, J.; Arulrajah, A.; Abdul Kadir, A. Nanoparticles in Construction Materials and Other Applications, and Implications of Nanoparticle Use. Materials 2019, 12, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Torgal, F.; Jalali, S. Nanotechnology: Advantages and Drawbacks in the Field of Construction and Building Materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olafusi, O.S.; Sadiku, E.R.; Snyman, J.; Ndambuki, J.M.; Kupolati, W.K. Application of Nanotechnology in Concrete and Supplementary Cementitious Materials: A Review for Sustainable Construction. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokrajac, L.; Abbas, A.; Chrzanowski, W.; Dias, G.M.; Eggleton, B.J.; Maguire, S.; Maine, E.; Malloy, T.; Nathwani, J.; Nazar, L.; et al. Nanotechnology for a Sustainable Future: Addressing Global Challenges with the International Network4Sustainable Nanotechnology. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 18608–18623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzein, B. Nano Revolution: “Tiny Tech, Big Impact: How Nanotechnology Is Driving SDGs Progress”. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ghida, D. L’Excellence dans la Revitalisation Urbaine: Une Mise en Valeur Architectonique des Marchés de Plein Air à Busan. Int. J. Innov. Appl. Stud. 2014, 7, 239–250. [Google Scholar]

- Tohlob, A.A.H.; Morsi, H.E.E.D. Nanotechnology and its impact on achieving sustainable architecture in Egypt. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Eng. Archit. 2024, 15, 138–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, H.; Taghdir, S.; Amrollahi, R.; Barzegar, Z. The Impact of Nanomaterials on Energy-Centric Form-Finding of Educational Buildings in Semi-Arid Climate. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ghida, D. Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality: A 360° Immersion into Western History of Architecture. Int. J. Emerg. Trends Eng. Res. 2020, 8, 6051–6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelini, M. Unravelling Art Practice and Education Entanglements in Academia: An Interview with Marco Buti. Arte, Individuo y Sociedad 2025, 37, 401–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macías-Silva, M.A.; Cedeño-Muñoz, J.S.; Morales-Paredes, C.A.; Tinizaray-Castillo, R.; Perero-Espinoza, G.A.; Rodríguez-Díaz, J.M.; Jarre-Castro, C.M. Nanomaterials in the Construction Industry: An Overview of Their Properties and Contributions in Building House. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 10, 100863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocco, L. Engineered Nanomaterials for Environmental and Health Applications. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Tang, M. Toxicity Mechanism of Engineered Nanomaterials: Focus on Mitochondria. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 343, 123231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanotechnology Environmental and Health Implications Working Group. National Nanotechnology Initiative Environmental, Health, and Safety Research Strategy: 2024 Update; National Science and Technology Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.nano.gov/sites/default/files/pub_resource/EHSResearchStrategy2024Update.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- OECD. Developments in Delegations on the Safety of Manufactured Nanomaterials and Advanced Materials between July 2023 and June 2024—Tour de Table; OECD Series on Safety of Manufactured Nanomaterials and Other Advanced Materials; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ghida, D.; Ben Ghida, S.; Ben Ghida, S. Rethinking Higher Education Post-COVID-19: Innovative Design Studio Teaching to Architecture Students. AIP Conf. Proc. 2024, 2799, 020107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Ben Ghida, D. Cast-in-Place Architectonic Concrete in South Korea: Methods and Specifications. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2017, 8, 820–829. [Google Scholar]

- Firoozi, A.A.; Firoozi, A.A.; Maghami, M.R. Transformative Impacts of Nanotechnology on Sustainable Construction: A Comprehensive Review. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 104973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onatayo, D.; Onososen, A.; Oyediran, A.O.; Oyediran, H.; Arowoiya, V.; Onatayo, E. Generative AI Applications in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction: Trends, Implications for Practice, Education & Imperatives for Upskilling—A Review. Architecture 2024, 4, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitina, N.P. The Relevance of Traditional Technologies in the Professional Training of Architects in a Technical University. Bull. Nizhnevartovsk State Univ. 2025, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ghida, D.; Ben Ghida, S. La Créativité dans la Réhabilitation Urbaine: Le Viaduc des Arts à Paris. Assoc. Cult. Fr.-Coréenne 2017, 35, 215–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellini, M. (Un)Touchable: The Caged Statues of the Chennai–Bangalore Expressway and the Landscapes of Resilience. Soc. Cult. South Asia 2024, 11, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellini, M.A. The Peacock Junction. GIS Gesto Imagem Som Rev. Antropol. 2021, 6, e178043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellini, M. Sonâmbulo: Anotações Sobre um Gesto na Penumbra e as Fotografias de André Leite Coelho. GIS Gesto Imagem Som Rev. Antropol. 2024, 9, e209366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).