Mechanical Behavior of Bioinspired Nanocomposites for Orthopedic Applications †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material Composition and Fabrication Techniques of Bioinspired Nanocomposites

2.1. Hydroxyapatite (HA) and Gelatin-Based Nanocomposites

2.2. Calcium Phosphate–Polymer Nanocomposites

2.3. Helical Rosette Nanotubes (HRNs) Combined with Hydroxyapatite

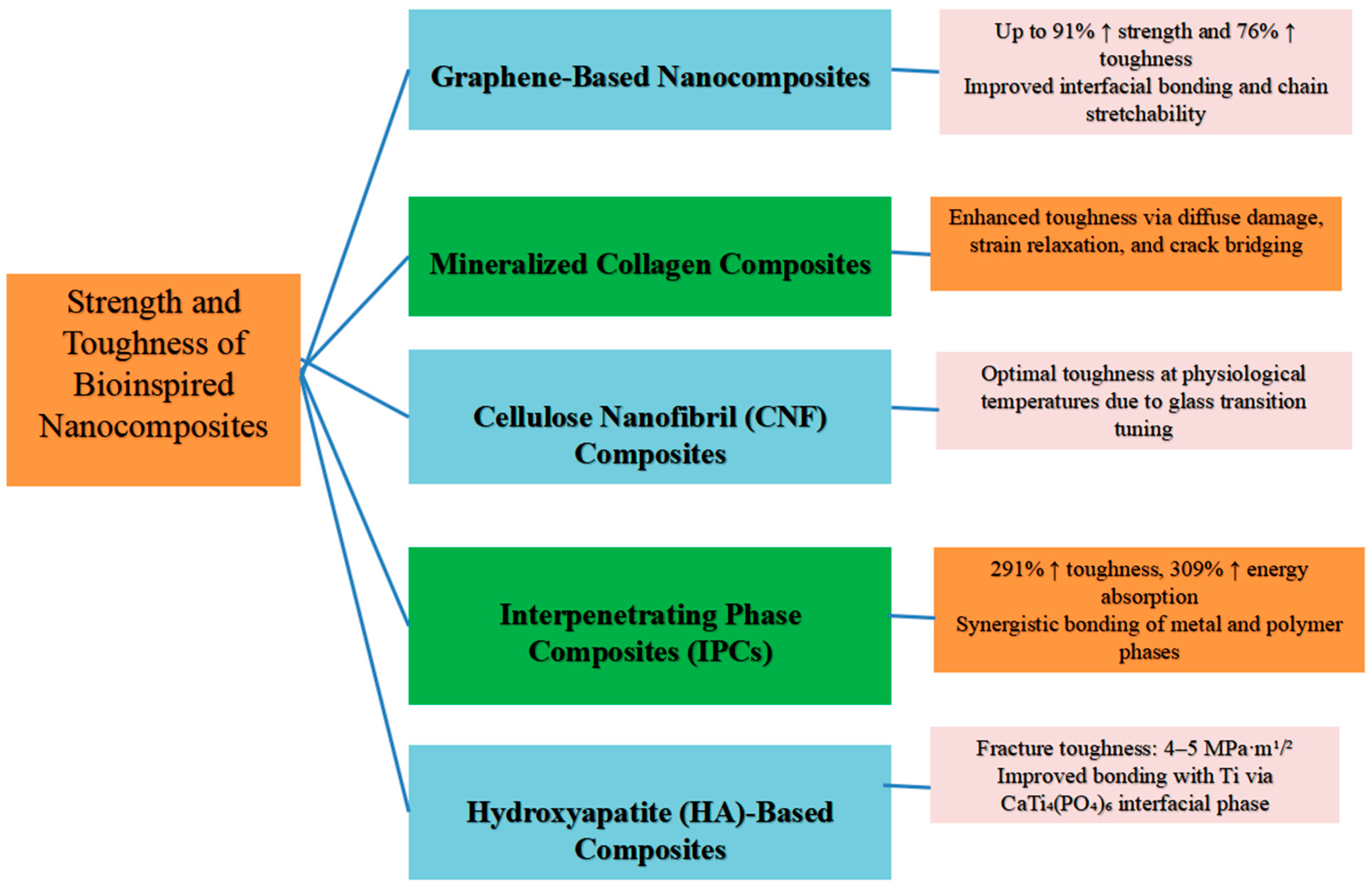

3. Strength and Toughness of Bioinspired Nanocomposites for Orthopedic Applications

4. Stiffness of Bioinspired Nanocomposites for Orthopedic Applications

5. Elastic Modulus of Bioinspired Nanocomposites for Orthopedic Applications

6. Biocompatibility and Bioactivity of Bioinspired Nanocomposites

7. Mechanisms by Which Bioinspired Nanocomposites Enhance Mechanical Properties

8. Applications of Bioinspired Nanocomposites in Orthopedics

9. Challenges of Bioinspired Nanocomposites in Orthopedics

10. Future Directions of Bioinspired Nanocomposites in Orthopedics

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Basirun, W.J.; Baradaran, S.; Nasiri-Tabrizi, B. Hydroxyapatite-graphene as advanced bioceramic composites for orthopedic applications. In Advanced 2D Materials; John Wiley & Son: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 473–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, K.; Ahmad, M.Z.; Sahariah, J.J.; Sahariah, M.; Konwar, S.; Talukdar, B.; Das, A.; Borthakur, P.P.; Gogoi, A. Bioinspired nanocarriers for advanced drug delivery. Nano Express 2025, 6, 032001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Castro, N.J.; Li, J.; Keidar, M.; Zhang, L.G. Greater osteoblast and mesenchymal stem cell adhesion and proliferation on titanium with hydrothermally treated nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite/magnetically treated carbon nanotubes. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2012, 12, 7692–7702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Li, J.; Lei, X.; Cheng, P.; Song, Y.; Gao, Y.; Hu, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, S.; Li, D.; et al. 3D-bioprinted functional and biomimetic hydrogel scaffolds incorporated with nanosilicates to promote bone healing in rat calvarial defect model. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 112, 110905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, M.; Thangavel, S.; Kumar, A. Biomimetic nanocomposites for orthopedic applications. In Nanomanufacturing Techniques in Sustainable Healthcare Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Lei, N.; Li, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, X. Constructing a biomimetic nanocomposite with the in situ deposition of spherical hydroxyapatite nanoparticles to induce bone regeneration. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 2469–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Zhou, C.; Jiang, C.; Huang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, J.; Liang, W.; Zeng, B. Recent developments in nanomaterials for upgrading treatment of orthopedic diseases. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1221365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streicher, R.M.; Schmidt, M.; Fiorito, S. Nanosurfaces and nanostructures for artificial orthopedic implants. Nanomedicine 2007, 2, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobini, S.; Javadpour, J.; Hosseinalipour, M.; Ghazi-Khansari, M.; Khavandi, A.; Rezaie, H.R. Synthesis and characterisation of gelatin-nano hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Adv. Appl. Ceram. 2008, 107, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azami, M.; Samadikuchaksaraei, A.; Poursamar, S.A. Synthesis and characterization of a laminated hydroxyapatite/gelatin nanocomposite scaffold with controlled pore structure for bone tissue engineering. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2010, 33, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedotov, A.Y.; Komlev, V.S.; Smirnov, V.V.; Fadeeva, I.V.; Barinov, S.M.; Ievlev, V.M.; Soldatenkov, S.A.; Sergeeva, N.S.; Sviridova, I.K.; Kirsanova, V.A.; et al. Hybrid composite materials based on chitosan and gelatin and reinforced with hydroxyapatite for tissue engineering. Inorg. Mater. Appl. Res. 2011, 2, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raz, M.; Moztarzadeh, F.; Shokrgoza, M.A.; Azami, M.; Tahriri, M. Development of biomimetic gelatin-chitosan/hydroxyapatite nanocomposite via double diffusion method for biomedical applications. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2014, 105, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-W.; Knowles, J.C.; Kim, H.-E. Porous scaffolds of gelatin-hydroxyapatite nanocomposites obtained by biomimetic approach: Characterization and antibiotic drug release. J. Biomed. Mater. Res.—Part B Appl. Biomater. 2005, 74, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.H.; Kim, S.-J.; Lee, W.-Y.; Song, H.-J.; Park, Y.-J. Hydrothermal fabrication and characterization of calcium phosphate anhydrous/chitosan composites. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 2786–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.J.; Qiu, H.; Kodali, P.; Yang, S.; Sprague, S.M.; Hwong, J.; Koh, J.; Ameer, G.A. Early tissue response to citric acid-based micro- and nanocomposites. J. Biomed. Mater. Res.—Part A 2011, 96, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, Z.; Jahanshahi, M.; Rabiee, S.M. Preparation of nanocomposite via calcium phosphate formation in chitosan matrix using in situ precipitation approach. Middle East J. Sci. Res. 2013, 13, 963–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Ghosh, S.; Ringu, T.; Pramanik, N. A focus on biomaterials based on calcium phosphate nanoparticles: An indispensable tool for emerging biomedical applications. BioNanoScience 2023, 13, 795–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Rodriguez, J.; Fenniri, H.; Webster, T.J. Biomimetic helical rosette nanotubes and nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium for improving orthopedic implants. Int. J. Nanomed. 2008, 3, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Rodriguez, J.; Fenniri, H.; Webster, T.J. Investigating helical rosette nanotubes and nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite as novel bone-like biomaterials for orthopedic applications. Techol. Proc. 2008 NSTI Nanotechnol. Conf. Trade Show 2008, 2, 214–217. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, A.L.; Fenniri, H.; Webster, T.J. Helical rosette nanotubes as a potentially more effective orthopaedic implant material. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 2005, 845, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Rodriguez, J.; Raez, J.; Myles, A.J.; Fenniri, H.; Webster, T.J. Biologically inspired rosette nanotubes and nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite hydrogel nanocomposites as improved bone substitutes. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 175101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Zeng, X.; Pidaparti, R.; Wang, X. Tough and strong bioinspired nanocomposites with interfacial cross-links. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 18531–18540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chathuranga, H.; Wasalathilake, K.C.; Marriam, I.; MacLeod, J.; Zhang, Z.; Bai, R.; Lei, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; et al. Preparation of bioinspired graphene oxide/PMMA nanocomposite with improved mechanical properties. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 216, 109046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Maghsoudi-Ganjeh, M.; Zeng, X. Computational investigation of the mechanical behavior of a bone-inspired nanocomposite material. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, A.J.; Lossada, F.; Zhu, B.; Rudolph, T.; Walther, A. Understanding toughness in bioinspired cellulose nanofibril/polymer nanocomposites. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 2417–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Biswas, K.; Basu, B. On the toughness enhancement in hydroxyapatite-based composites. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 5198–5215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, F.; Wang, R.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Luo, T.; Zhang, K.; Cao, J. Ti-PEEK interpenetrating phase composites with minimal surface for property enhancement of orthopedic implants. Compos. Struct. 2024, 327, 117689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiazhagan, S.; Anup, S. Influence of platelet aspect ratio on the mechanical behaviour of bio-inspired nanocomposites using molecular dynamics. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2016, 59, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Dong, H.; Wang, P. Research progress on nanocellulose and its composite materials as orthopedic implant biomaterials. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 87, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandiah, K.; Venkatachalam, R.; Wang, C.; Valiyaveettil, S.; Ganesan, K. In vitro and preliminary in vivo toxicity screening of high-surface-area TiO2-chondroitin-4-sulfate nanocomposites for bone regeneration application. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2015, 128, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, T.; Xavier, J.R.; Cross, L.; Jaiswal, M.K.; Mondragon, E.; Kaunas, R.; Gaharwar, A.K. Photocrosslinkable and elastomeric hydrogels for bone regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res.—Part A 2016, 104, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taymour, N.; Fahmy, A.E.; Gepreel, M.A.H.; Kandil, S.; El-Fattah, A.A. Improved mechanical properties and bioactivity of silicate based bioceramics reinforced poly(ether-ether-ketone) nanocomposites for prosthetic dental implantology. Polymers 2022, 14, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilberforce, S.I.J.; Best, S.M.; Cameron, R.E. A dynamic mechanical thermal analysis study of the viscoelastic properties and glass transition temperature behaviour of bioresorbable polymer matrix nanocomposites. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2010, 21, 3085–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhou, J.; Han, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, S.; Chen, S.; He, D.; Wu, Y.; et al. Bionic nanostructures create mechanical signals to mediate the composite structural bone regeneration through multi-system regulation. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e02299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, C.; Xiao, J.; Qin, Y. Applications of nanotechnology in hip implants. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 662, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Webster, T.J. Nano-dispersed particulate ceramics in poly-lactide-co-glycolide composites improve implantable bone substitute properties. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 2008, 1056, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, D.; Rouzaud, F.; Richard, T.; Keshri, A.K.; Bakshi, S.R.; Kos, L.; Agarwal, A. Boron nitride nanotube reinforced polylactide-polycaprolactone copolymer composite: Mechanical properties and cytocompatibility with osteoblasts and macrophages in vitro. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 3524–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida Neto, G.R.; Barcelos, M.V.; Rodríguez, R.J.S.; Gomez, J.G.C. Influence of encapsulated nanodiamond dispersion on P(3HB) biocomposites properties. Mater. Res. 2017, 20, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dubey, U.; Kesarwani, S.; Verma, R.K. Incorporation of graphene nanoplatelets/hydroxyapatite in PMMA bone cement for characterization and enhanced mechanical properties of biopolymer composites. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2023, 36, 1978–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, A.J.; Mano, J.F. Biomedical applications of natural-based polymers combined with bioactive glass nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 4555–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Wan, Y.; Peng, M.; Yang, Z.; Luo, H. Incorporating nanoplate-like hydroxyapatite into polylactide for biomimetic nanocomposites via direct melt intercalation. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 185, 107903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajide, J.L.; Desai, D.A.; Ajibola, J.O.; Adekoya, G.J.; Daramola, O.O.; Alaneme, K.K.; Fasiku, V.O.; Sadiku, E.R. Nosocomial bacterial infection of orthopedic implants and antibiotic hydroxyapatite/silver-coated halloysite nanotube with improved structural integrity as potential prophylaxis. In Antibiotic Materials in Healthcare; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 171–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, Y.; Yang, L.; Shi, Z.; Yang, P.; Cheng, G. In vitro bioactivity and biocompatibility of bio-inspired Ti-6Al-4V alloy surfaces modified by combined laser micro/nano structuring. Molecules 2020, 25, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthakur, P.P. Nanoparticle enhanced biodiesel blends: Recent insights and developments. Hybrid Adv. 2025, 10, 100442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anil, S.; Suresh, N.; Sweety, V.K.; Suraj, A.R.; Thomas, N.G. Biocompatible nanocomposites: An overview of materials used in biomedical applications. Adv. Struct. Mater. 2025, 239, 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthakur, P.P. The Role and Future Directions of 3D Printing in Custom Prosthetic Design. Eng. Proc. 2024, 81, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthakur, P.P.; Das, A.; Sahariah, J.J.; Pramanik, P.; Baruah, E.; Pathak, K. Revolutionizing Patient Care: 3D Printing for Customized Medical Devices and Therapeutics. Biomed. Mater. Devices 2025, 3, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Rumi, M.J.U.; Zeng, X. Computational investigation of the mechanical response of a bioinspired nacre-like nanocomposite under three-point bending. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodhi, R.S.; Das, P. Bioinspired nanocomposites of sodium carboxymethylcellulose and polydopamine-modified cellulose nanocrystals for UV-protective packaging. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 16580–16594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, F.G.; Saavedra, A.C. A comparison between the failure modes observed in biological and synthetic polymer nanocomposites. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Mater. 2020, 59, 241–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lossada, F.; Guo, J.; Jiao, D.; Groeer, S.; Bourgeat-Lami, E.; Montarnal, D.; Walther, A. Vitrimer chemistry meets cellulose nanofibrils: Bioinspired nanopapers with high water resistance and strong adhesion. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lossada, F.; Hoenders, D.; Guo, J.; Jiao, D.; Walther, A. Self-assembled bioinspired nanocomposites. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 2622–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Nguyen, L.T.H.; Ngiam, M.; Wang, C.; Cheng, Z.; Chan, C.K.; Ramakrishna, S. Biomimetic nanocomposites to control osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2014, 3, 737–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X.-T.; Rao, C.-Y.; Li, T.; Zhou, R.-H. Research progress in biomimetic synthesis of nano-hydroxyapatite in bone tissue engineering. J. Sichuan Univ. (Med. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 52, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaczek-Moczydłowska, M.A.; Joszko, K.; Kavoosi, M.; Markowska, A.; Likus, W.; Ghavami, S.; Łos, M.J. Biomimetic natural biomaterial nanocomposite scaffolds: A rising prospect for bone replacement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugavadivu, A.; Lavanya, K.; Selvamurugan, N. Nanomaterials in bone tissue engineering. In Handbook of Nanomaterials, Volume 2: Biomedicine, Environment, Food, and Agriculture; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, M.; Matsumoto, T. Fabrication methods of hydroxyapatite nanocomposites. Nano Biomed. 2016, 8, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ghori, S.W.; Tirth, V. Biocomposites for orthopedic implants. In Green Biocomposites for Biomedical Engineering: Design, Properties, and Applications; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirdar, M.R.; Farajpour, N.; Shahbazian-Yassar, R.; Shokuhfar, T. Nanocomposite materials in orthopedic applications. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2019, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christenson, E.M.; Anseth, K.S.; Van den Beucken, J.J.J.P.; Chan, C.K.; Ercan, B.; Jansen, J.A.; Laurencin, C.T.; Li, W.-J.; Murugan, R.; Nair, L.S.; et al. Nanobiomaterial applications in orthopedics. J. Orthop. Res. 2007, 25, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Chiu, T.-H.; Li, B.-Y.; Yu, C.-C.; Wei, H.-X.; Yeh, Y.-C. Nanocomposite hydrogels and their emerging applications in orthopedics. In Nanocomposite Hydrogels and their Emerging Applications; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 191–213. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85167863324 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Sun, T.-W.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Chen, F. Hydroxyapatite nanowire/collagen elastic porous nanocomposite and its enhanced performance in bone defect repair. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 26218–26229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, Z.; Tao, J.; Wang, B.; He, C. Bamboo-inspired crack-face bridging fiber reinforced composites simultaneously attain high strength and toughness. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2308070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladani, R.B.; Ravindran, A.R.; Wu, S.; Pingkarawat, K.; Kinloch, A.J.; Mouritz, A.P.; Ritchie, R.O.; Wang, C.H. Multi-scale toughening of fibre composites using carbon nanofibres and z-pins. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2016, 131, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Liu, J.; Dong, J.; Liang, Y.; Du, T.; Fan, H.; Zhang, Q. Tailorable nanoconfinement enables nacreous biomimetic graphene/silicate composites with ultrahigh strength and toughness. Carbon 2025, 240, 120364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeri, M.J.; Putz, K.W.; Brinson, L.C. Sacrificial bonds in stacked-cup carbon nanofibers: Biomimetic toughening mechanisms for composite systems. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 4256–4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrow, J.K.; Gaharwar, A.K. Bioinspired polymeric nanocomposites for regenerative medicine. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2015, 216, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banskota, B.; Bhusal, R.; Banskota, A. Advanced materials in orthopedics. In Biomaterials in Orthopaedics & Trauma: Current Status and Future Trends in Revolutionizing Patient Care; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes Vieira, L.A.; Nunes Marinho, J.P.; Rodrigues, M.A.; Basílio de Souza, J.P.; Geraldo de Sousa, R.; Barros de Sousa, E.M. Nanocomposite based on hydroxyapatite and boron nitride nanostructures containing collagen and tannic acid ameliorates the mechanical strengthening and tumor therapy. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 32064–32080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirugnanasambandam, A.; Nallamuthu, R.; Narayanaswamy, N.; Rangappa, S.M.; Siengchin, S.; Kechagias, J.D. A comprehensive investigation of the 3D printed polylactic acid/yttria-stabilized zirconia nanocomposite scaffold for orthopedic applications. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 139, 929–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjong, S.C. Advances in Biomedical Sciences and Engineering; Bentham Science Publishers: Singapore, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Zhou, C.; Li, Q.; Liu, L.; Jiang, C.; Dai, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, J.; Liang, W. Nanotechnology in orthopedic care: Advances in drug delivery, implants, and biocompatibility considerations. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 9251–9274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-K.; Lee, H.; Kang, M.-H.; Hwang, C.; Kim, H.-E.; Oudega, M.; Jang, T.-S.; Jung, H.-D. Bioinspired nanotopography for combinatory osseointegration and antibacterial therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 30967–30979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, K.-S.; Deng, C.-C.; Wang, X.-X.; Li, Y.-C.; Zhou, C.; Zhao, C.-R.; Dai, X.-Z.; Khan, A.-R.; Zhang, Z.; Guidoin, R.; et al. Research advances and future perspectives of zinc-based biomaterials for additive manufacturing. Rare Met. 2025, 44, 4376–4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, R.; Zhu, D.; Abdulmalik, S.; Wijekoon, S.; Wei, G.; Kumbar, S.G. Stimuli-responsive peptide assemblies: Design, self-assembly, modulation, and biomedical applications. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 35, 181–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Liang, X.; Cui, L.; Guan, D.; Qu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Guan, K. Magnesium-based nanocomposites for orthopedic applications: A review. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 4335–4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Hu, Z.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, K.; Li, Z.; Yuan, C.; Ge, X. Recent advances in antibacterial strategies based on TiO2 biomimetic micro/nano-structured surfaces fabricated using the hydrothermal method. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A. A feasibility study of the bioinspired green manufacturing of nanocomposite materials. In Bioinspired and Green Synthesis of Nanostructures: A Sustainable Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 231–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.Z.; Mustafa, G.; Abdel-Wahab, B.A.; Pathak, K.; Das, A.; Sahariah, J.J.; Kalita, P.; Alam, A.; Borthakur, P.P. From bench to bedside: Advancing liposomal doxorubicin for targeted cancer therapy. Results Surf. Interfaces 2025, 19, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composite Type | Materials | Fabrication Techniques | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| HA/gelatin nanocomposites | Hydroxyapatite, gelatin | Freeze-drying, solvent casting, in situ precipitation | High porosity, biocompatibility, enhanced cell attachment [9,10] |

| Calcium phosphate–polymer | Calcium phosphate, chitosan, POC | In situ precipitation, hydrothermal synthesis, solvent evaporation | Mechanical strength, bioresorbability, controlled crystal growth [14,15] |

| HRNs/HA composites | Helical rosette nanotubes, nanocrystalline HA | Self-assembly, hydrothermal treatment | Osteoconductivity, enhanced osteoblast adhesion, collagen mimicry [19,20] |

| Nanocomposite Matrix | Reinforcement | Elastic Modulus Improvement | Additional Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLGA | Titania | Increased compressive and tensile modulus [36] | Stress-shielding reduction |

| PLC | BNNTs | 1370% increase [37] | Improved tensile strength, osteoblast viability |

| PEEK | Forsterite | Significant improvement [32] | Bioactivity for long-term implants |

| P(3HB) | Nanodiamonds | Higher storage modulus [38] | Better thermal and mechanical properties |

| PMMA | GnP + HA | Higher flexural and compressive modulus [39] | Suitability for joint replacements |

| Application | Description | Material | Properties | Benefits | Challenges | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone regeneration | Mimicking natural bone structure for effective bone healing | Biomimetic nanocomposites | Enhanced biocompatibility, osteoconductivity | Improved bone healing and integration | Complex manufacturing processes | [5,21,40,53,54] |

| Joint replacements | Replacing damaged joints with nanocomposite materials | Nanostructured coatings | Anti-corrosion, bone ingrowth, anti-infection | Long-term success of prosthesis | Regulatory issues | [5,43,54] |

| Cartilage repair | Repairing damaged cartilage using nanocomposite hydrogels | Nanocomposite hydrogels | Mechanical strength, injectability | Enhanced clinical outcomes | Standardization issues | [5,61] |

| Spinal fusion | Fusing vertebrae using nanocomposite materials | Biomimetic nanocomposites | Enhanced mechanical properties | Improved spinal stability | Complex manufacturing processes | [5] |

| Soft tissue repair | Repairing soft tissues with nanocomposite scaffolds | Nano-biocomposite scaffolds | Mimicking extracellular matrix | Enhanced tissue integration | Standardization issues | [5] |

| Bone cement | Using biocomposites for bone cement applications | Biocomposites | Biocompatibility, biodegradability | Improved bone fixation | Manufacturing challenges | [58] |

| Bone grafts | Utilizing biocomposites for bone grafts | Biocomposites | Light weight, greater stiffness | Enhanced bone regeneration | Manufacturing challenges | [58] |

| Hip joint replacement | Replacing hip joints with biocomposite materials | Biocomposites | Biocompatibility, mechanical properties | Long-term performance | Regulatory issues | [58] |

| Implant coatings | Coating implants with nanostructured materials | Nanostructured coatings | Enhanced osteoblast adhesion | Improved osseointegration | Manufacturing challenges | [3] |

| Bone defect repair | Repairing bone defects with biomimetic nanocomposites | Biomimetic porous nanocomposites | Improved mechanical properties | Enhanced bone regeneration | Manufacturing challenges | [62] |

| Material System | Strength | Elastic Modulus | Toughness | Fatigue Performance | Advantages | Disadvantages | Key Reinforcement/Toughening Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epoxy resin/carbon nanocomposite | High (≈430.8 MPa) [63] | Moderate–high (≈10–20 GPa) | High (8.3 MPa·m1/2) [63]. | Moderate | Exceptional strength and toughness; superior crack-face bridging and CNT pull-out; multifunctional reinforcement | Complex dispersion control; limited biodegradability | Interface stress transfer, CNT bridging, crack deflection, and crack-face bridging |

| PLA/TCP composite | Porosity-dependent (varies with hydration) [48]. | Moderate (1–3 GPa) | Variable; declines with hydration | Low–moderate | Biodegradable, bioresorbable, and osteoconductive; tunable porosity | Decreased mechanical stability; limited fatigue life | Interfacial bonding, microcrack pinning, and porosity-driven crack arrest |

| Magnesium, zinc, and iron alloys | High (Mg: 200–400 MPa; Zn: 250 MPa; Fe: >400 MPa) [65]. | High (45–210 GPa) | Moderate | High | Superior load-bearing strength, biodegradability, biocompatibility, and wear resistance | Rapid corrosion and hydrogen evolution | Interface stress transfer and nanoscale corrosion layer toughening |

| Nacre-inspired ceramic/graphene–silicate composite | Moderate (26.39 MPa) [65]. | High (≈40 GPa) [65]. | Moderate–high (1.5 MPa·m1/2) | High | High stiffness-to-weight ratio; hierarchical layered structure; excellent energy dissipation | Complex fabrication; brittleness under tension | Crack deflection, platelet sliding, and hierarchical interlocking |

| CMC–DCNC nanocomposite | High (183 MPa) [49] | High (≈15 GPa) | High | Moderate | Excellent toughness and flexibility; UV-shielding; sustainable components | Performance varies with humidity; limited bioactivity | Hydrogen bonding, nanoparticle bridging, and sacrificial bond formation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pathak, K.; Deka, S.; Baruah, E.; Borthakur, P.P.; Deka, R.; Medhi, N. Mechanical Behavior of Bioinspired Nanocomposites for Orthopedic Applications. Mater. Proc. 2025, 25, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2025025012

Pathak K, Deka S, Baruah E, Borthakur PP, Deka R, Medhi N. Mechanical Behavior of Bioinspired Nanocomposites for Orthopedic Applications. Materials Proceedings. 2025; 25(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2025025012

Chicago/Turabian StylePathak, Kalyani, Simi Deka, Elora Baruah, Partha Protim Borthakur, Rupam Deka, and Nayan Medhi. 2025. "Mechanical Behavior of Bioinspired Nanocomposites for Orthopedic Applications" Materials Proceedings 25, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2025025012

APA StylePathak, K., Deka, S., Baruah, E., Borthakur, P. P., Deka, R., & Medhi, N. (2025). Mechanical Behavior of Bioinspired Nanocomposites for Orthopedic Applications. Materials Proceedings, 25(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2025025012