Abstract

Positional accuracy is crucial in target tracking for various robotic applications, where precise movement and response are essential. Geared electromechanical actuators, widely used in robotic systems, offer significant advantages but are susceptible to backlash, particularly during direction reversals. This backlash can introduce unwanted oscillations and disturbances, especially in systems with swinging loads, thereby compromising tracking performance. This study proposes a novel backlash compensation technique for inverted pendulum systems utilizing observer estimators. The proposed method effectively estimates and mitigates the disturbances caused by backlash, enhancing the system’s ability to maintain accurate target tracking. RMSE turns out to be 0.18 and settling time is quite minimal 2.4sec.Simulation results demonstrate that this approach significantly improves tracking performance, ensuring robust and reliable operation in dynamic environments.

1. Introduction

Target tracking is a critical requirement in various industrial robotic applications, where precision and accuracy are paramount. Consequently, achieving perfect target tracking has been a major focus of research and development in the field of robotics. However, backlash—a common issue in geared electromechanical actuators—introduces errors that can significantly impact tracking performance. Backlash occurs during direction reversals, causing a lag in movement that disrupts the synchronization of the system, leading to positional inaccuracies and unstable control responses. Addressing this challenge is essential for enhancing the reliability and efficiency of industrial robots in dynamic and complex environments.

To eliminate backlash and frictional effects in rack and pinion model, Karim et al. [1] presented simlified Rack-and-pinion which utilises control-based technique. The goal is to replace current compensatory measures with a financially viable option by utilizing MEMS accelerometers.The approach results in a strategy that effectively counteracts the negative effects of backlash and friction by analyzing the drive’s current acceleration and using a reduced rack-and-pinion model. However, gears have a tendency to break down. Backlash characteristics often vary due to gear wear. Monitoring changes in the backlash parameters over time is essential for effective backlash adjustment. This finding led to the introduction of dynamic models in previous works [2,3] for backlash in gears with time-varying behavior.

A new nonlinear dynamic model for spur gears was presented in 2019 by Yi et al. [2]. Numerous elements were taken into account in this model, including geometrical imbalance in mass, excitations, gear backlash behaviors, and pressure angle variation with time. In Park’s (2020) [3] study, the gears in the backlash were used as the starting point, and meshes that varied with bearing stiffness and time were added to examine how spur gears moved and responded.

The mitigation of backlash has been done by various techniques. Precision manufacturing enables zero backlash in the system. The development of these drives are not only costly, but they also require precsion machining and manufacturing. However, still backlash might arise in certain situations.

Some other classes reduce backlash by evaluating the parameters that may prevent backlash and later on by including backlash uncertainties into the models themselves. Researchers have put forth a number of methods that can be employed to achieve the goal of compensating backlash. Backlash models were introduced by Voros et al. [4], who used the switching function to build an analytical description of the backlash. Estimating internal variables allowed for the division of the parameters. Huo 2019 [5] explained hysteresis nonlinearities by use of a system of differential equations.It addresses the problem of adaptive fuzzy output feedback tracking control and specialized function approximators to approximate the nonlinear functions of the system.This method has used a MIMO switched fuzzy observer to address the issue of unmeasured states, and the dynamic surface control technique is presented to prevent the recurrence of differentiations that are present in the majority of conventional backstepping systems.

Researchers have employed dead zone linearity extensively to define the backlash [6,7,8]. According to [7,8], accurate dead zone estimation improves servo tracking performance and accuracy. In [9], a predictive control technique was used for an electric power train system with backlash in order to address the issue. A flipped Kalman filter was employed by the researchers to get around the immeasurable system states. Using real-time model predictive control, Rostiti [10] introduced a revolutionary backlash compensation for automobile drivetrains. Several adaptive control techniques for backlash compensation were also developed by [11,12,13,14,15,16,17] since predictive control schemes require repeated computations.

For robot manipulators with unknown backlash in robot joint gears, an adaptive robust controller was built without utilizing the inverse backlash model established by Abher et al. [16]. The controller was less complicated because it did not employ the inverse backlash technique. To manage the system’s backlash, He et al. (2018) developed a boundary controller [17] for a flexible robotic manipulator. Using touch-state observation, Wang et al. [18] developed an adaptive method for adjusting for backlash in a solid-ducted rocket. The technique was effective in shortening the transition’s time and reducing the impact of hysteresis on the control system.

The identification of parameters in a system which contains input nonlinearities like backlash. Bai [19] worked on identification of such system with input nonlinearities of known structures. A deterministic technique was used for input nonlinearities based on separable least squares.The problem is minimized to one-dimension. The identification approach is dependent on correlation analysis.

Guofa et al. [20] developed a technique to calculate system states and vibration torque. Those estimated characteristics were employed by a constructed extended-state observer to generate feed-forward and feed-back signals.

Additionally, Sun et al. [21] developed a novel method for repairing servo systems that exhibit backlash. It is referred to as accurate differential observer-based compensation control for servo systems with backlash using variable gain-switching. Based on a mathematical model of switching backlash torque, the variable gain technique was developed to accurately forecast the unknown system states and account for the influence of backlash. The backlash was considered as a parameter and included as a state in the dynamics throughout the estimation process, which was carried out using the Kalman filter. The DFIG system’s local measurements were used to estimate the backlash.

Dual-motor drives were employed by Sven et al. [22] to account for backlash. To close the gear gap, one of the drives functioned as a rotating spring. Refs. [23,24] also used dual motors for backlash compensation by using mode estimator.Through cooperative control via, two degrees of freedom backlash-free mechanisms have been constructed by using the drive-anti-drive mechanism developed by Haider et al. [25].

Contributions

In an inverted pendulum system, accurate control heavily depends on estimating and compensating for external disturbances, such as load torque. The system’s load may be known in certain cases, but in others, it remains unknown, making it essential to estimate the load torque effectively.When the load torque is unknown or time-varying (e.g., due to external forces or changing environmental conditions), an estimation mechanism is necessary to adapt to these changes dynamically. In many cases, not all states of the inverted pendulum system can be directly measured due to sensor limitations or the complexity of the system. To address this, an observer can be implemented to estimate the states and the unknown load torque by using available system outputs such as angular position and velocity.

2. Observer Control of Inverted Pendulum Driven by Drive-Anti Drive Mechanism

The section deals with the model of inverted Pendulum driven by Drive-Anti Drive Mechanism. The constant torque has been maintained by the current regulation as achieved by [26].

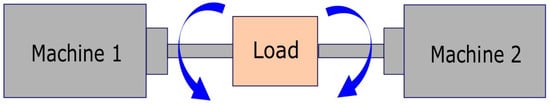

The drive-anti drive system directs the load into the direction with higher torque level. Both machines torques are represented as and , respectively. In order to ensure positive coupling of gears, torque is consistently provided in opposite directions to both drives, as depicted in Figure 1. Equation (3) states that the resultant torque acting on load is determined by the difference between driving torques and drives the load in the direction of greater torque.

Backlash compensation necessitates the maintenance of a minimum level of grasping torque to ensure proper contact between the gears, as specified by Equation (5).

Equation (6) describes the mechanical behaviour of the motor and the applied load. The equation demonstrates that the net driving torque is equivalent to the sum of the load torque and the inertial and frictional torques. The variables J and B represent the moment of inertia and friction coefficient of the rotating mass.

Equation (6) clearly demonstrates that an increase in speed leads to a corresponding increase in friction.

The dynamical model of Drive-Anti Drive yields the differential equation denoted as Equation (8).

The variable denotes an extra friction coefficient resulting from the coupling torque. Assigning the value of to Equation (8) yields.

Figure 1.

Drive Anti-Drive Dynamic Model.

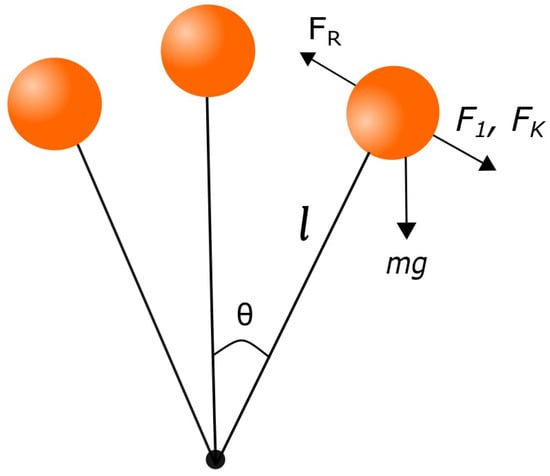

Given the continuous oscillation of the pendulum, represents the inertial force, while denotes the reactional force developed in the result of motion. The other factor is the component of force that arises from the acceleration caused by gravity, as depicted in Figure 2. The gravitational function is Angular Velocity dependent.

where, m represents the mass of strings, l denotes the length, g represents the acceleration due to gravity, and frictional forces act in the opposite direction of the applied force. The frictional forces have a direct proportionality to the angular velocity. Solution of forces acting on a system results in a differential equation. A differential equation may be expressed as;

Further reduction of the differential equation is derived as:

Since both angular velocity and angular position are continuously changing, they are considered as the states of the system. The angular position is taken as state 1, while the angular velocity is taken as state 2. Mathematically, we define the system states as follows and .

Figure 2.

Free body diagram of pendulum in presence of friction.

State space of the inverted pendulum driven by the Drive-Anti Drive model is defined by Equation (13).

The output of the system has been taken as angular position is given by Equation (14).

The swinging pendulum, used as the load, experiences continuous variations in both the magnitude and direction of the load torque due to gravitational forces.

Plant is represented below. Disturbance has been modeled as per the equation below.

State equation of the pendulum describes a plant, with state x and input u subjects to the disturbance represented by

where , , and Exo-system models the class of reference signals and disturbance to be rejected. Derivative information is also encapsulated in the information of exo-system w refers to model the class of reference and disturbance signal. Here R refers to model the reference and its derivative.

D refers to model the class of disturbance and its derivative.

, depicts error between actual output and a reference signal.

and

models the disturbance which needs to be rejected that is . models the reference which needs to be tracked.

Output Regulation has to be done when all the states of the system start following required reference. Error converges to zero in a finite time.

3. Controller for Output Regulation

Output Regulation problem through full information feedback is solvable if following conditions are satisfied.

- When Eigen values of S are non-negative integers.

- The pair (A,B) is stablizable.

If all conditions get satisfied then suitable feedback is given by

Here w has the knowledge of reference signal as well as the unwanted disturbance which we want to reject.

3.1. Observer Design

3.1.1. Plant

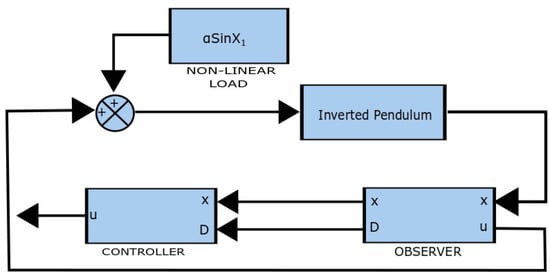

When not all states are observable, state estimates can still be generated by appropriately designing an observer as shown in Figure 3. In this model, the disturbance was unknown, so a state estimate was produced to compensate for the lack of direct observation.

Figure 3.

Observer Design.

3.1.2. Output Feedback Tracking Control

Observer gain has been chosen in such a way such that eigen values of are in left half plane. The error dynamics of the observer are governed by the poles of the matrix , where H is the observer gain matrix. The matrix H is designed to place the eigenvalues of in the left half of the complex plane, ensuring that the estimation error decays over time, leading to accurate state estimation.

Mathematically, this can be represented as:

where: is the estimated state vector, u is the input to both the plant and the observer, y is the actual measured output, is the estimated output, A and B represent the system matrices, H is the observer gain matrix.

The error dynamics are given by:

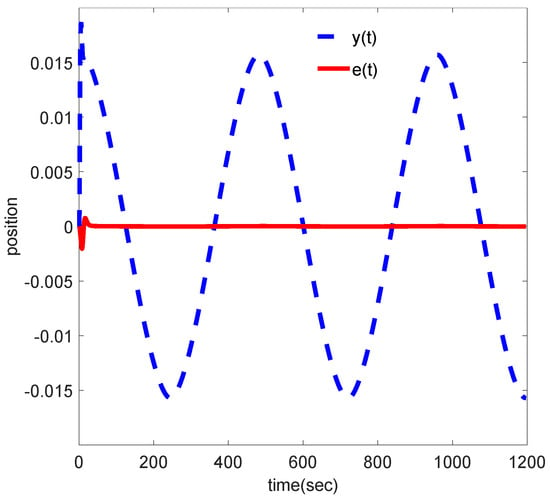

where is the estimation error. To ensure the estimation error converges to zero, H is chosen such that the eigenvalues of lie in the left half of the complex plane, guaranteeing stability as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Output and Error of the system.

4. Results

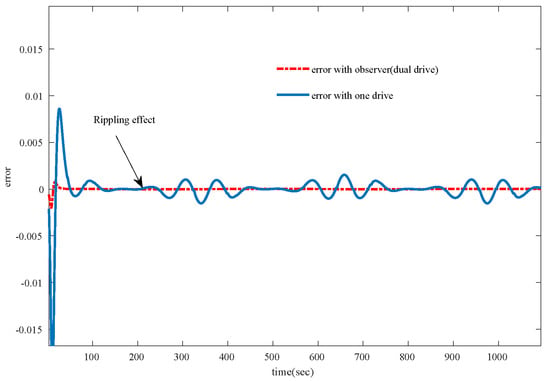

The proposed control system incorporates an observer gain that plays a critical role in estimating external disturbances, particularly unknown and varying torques, which impact the pendulum’s positional accuracy. By leveraging the observer, the system can compensate for these disturbances in real time, thereby maintaining the pendulum’s targeted trajectory more effectively.

To evaluate the system’s performance, a reference trajectory was provided to the control system, and the error between the reference and the actual position was plotted over time. The results demonstrate a significant reduction in both steady-state error and transient response when compared to conventional control systems lacking the observer-based disturbance estimation. The proposed system’s ability to estimate and compensate for unknown disturbances resulted in a notably reduced steady-state error. Unlike traditional systems where unaccounted external forces lead to residual positional errors, the observer gain enables real-time disturbance correction, allowing the system to achieve and maintain the desired position with high accuracy.

In addition to enhancing steady-state performance, the observer gain had a profound impact on the system’s transient response. During the initial phases of movement, where torque disturbances are often more prominent, the system exhibited faster settling times and reduced overshoot. This improvement is attributed to the precise disturbance estimation, which enables the controller to apply corrective measures earlier, thus minimizing the effects of transient errors.

The overall improvement in these key control metrics—steady-state error and transient response—highlights the effectiveness of the proposed system in achieving more accurate and stable pendulum tracking in comparison to traditional approaches as depicted in Figure 5, even in the presence of dynamic and unpredictable disturbances. These results confirm the efficacy of using observer-based disturbance compensation in enhancing control performance, especially in applications where external forces are not fully predictable.

Figure 5.

Error comparison of Observer based Dual Drive vs. One Motor.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents a novel control strategy incorporating observer-based disturbance estimation to mitigate the effects of unknown varying torque in an inverted pendulum system. By accurately estimating external disturbances in real time, the system significantly reduces both steady-state error and improves transient response, demonstrating enhanced positional accuracy and stability. The proposed method outperforms traditional control systems, which typically struggle with unpredictable disturbances. The results validate the effectiveness of the observer gain in compensating for unknown forces, making the system more robust and reliable. Future research may focus on extending this approach to other dynamic systems and refining the model to handle even more complex disturbance profiles, further broadening its industrial applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.A. and U.S.K.; methodology, A.A.A.; software, A.A.A.; validation, A.A.A. and U.S.K.; formal analysis, A.A.A.; investigation, A.A.A.; resources, A.A.A., U.S.K. and T.N.; data curation, A.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.A., U.S.K. and T.N.; writing—review and editing, A.A.A., U.S.K. and T.N.; visualization, A.A.A.; supervision, U.S.K.; project administration, U.S.K.; funding acquisition, A.A.A., U.S.K. and T.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Karim, A.; Lindner, P.; Verl, A. Control-based compensation of friction and backlash within rack-and-pinion drives. Prod. Eng. 2018, 12, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Huang, K.; Xiong, Y.; Sang, M. Nonlinear dynamic modelling and analysis for a spur gear system with time-varying pressure angle and gear backlash. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 132, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.I. Dynamic behavior of the spur gear system with time varying stiffness by gear positions in the backlash. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2020, 34, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vörös, J. Modeling and identification of systems with backlash. Automatica 2010, 46, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, X.; Ma, L.; Zhao, X.; Niu, B.; Zong, G. Observer-based adaptive fuzzy tracking control of MIMO switched nonlinear systems preceded by unknown backlash-like hysteresis. Inf. Sci. 2019, 490, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, C. A new adaptive control of dual-motor driving servo system with backlash nonlinearity. Sādhanā 2018, 43, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Huo, X.; Zhao, X.; Niu, B.; Zong, G. Adaptive neural control for switched nonlinear systems with unknown backlash-like hysteresis and output dead-zone. Neurocomputing 2019, 357, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, D.; Blanke, M.; Niemann, H.H.; Richter, J.H. Robust Backlash Estimation for Industrial Drive-Train Systems—Theory and Validation. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2018, 27, 1847–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formentini, A.; Oliveri, A.; Marchesoni, M.; Storace, M. A Switched Predictive Controller for an Electrical Powertrain System with Backlash. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 32, 4036–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostiti, C.; Liu, Y.; Canova, M.; Stockar, S.; Chen, G.; Dourra, H.; Prucka, M. A Backlash Compensator for Drivability Improvement Via Real-Time Model Predictive Control. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control. Trans. ASME 2018, 140, 104501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Tong, S. Adaptive fuzzy control for a class of nonlinear discrete-time systems with backlash. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2013, 22, 1359–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, G.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.L.P. Adaptive Fuzzy Tracking Control of Nonlinear Systems with Asymmetric Actuator Backlash Based on a New Smooth Inverse. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2015, 46, 1250–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tong, S. Adaptive Fuzzy Output-Feedback Stabilization Control for a Class of Switched Nonstrict-Feedback Nonlinear Systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2016, 47, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, G.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.L.; Xie, S. Adaptive Inversion-Based Fuzzy Compensation Control of Uncertain Pure-Feedback Systems with Asymmetric Actuator Backlash. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2016, 25, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, J.; Chen, W. Practical adaptive fuzzy tracking control for a class of perturbed nonlinear systems with backlash nonlinearity. Inf. Sci. 2017, 420, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhari, S.A.; Hashemzadeh, F.; Baradarannia, M.; Kharrati, H. An adaptive robust control scheme for robot manipulators with unknown backlash nonlinearity in gears. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2018, 41, 2789–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; He, X.; Zou, M.; Li, H. PDE Model-Based Boundary Control Design for a Flexible Robotic Manipulator with Input Backlash. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2018, 27, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Zeng, Q.; Ma, L.; Wang, H. Adaptive Backlash Compensation Method Based on Touch State Observation for a Solid Ducted Rocket. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2020, 2020, 6698158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, E.W. Identiÿcation of Linear Systems with Hard Input Nonlinearities of Known Structure; Springer: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Q. Observer-based compensation control of servo systems with backlash. Asian J. Control 2021, 23, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G. Variable gain switching exact differential observer-based compensation control for servo system with backlash. IET Control Theory Appl. 2021, 15, 1789–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertz, S.G.; Halt, L.; Kelkar, S.; Nilsson, K.; Robertsson, A.; Schär, D.; Schiffer, J. Precise robot motions using dual motor control. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Anchorage, AK, USA, 3–7 May 2010; pp. 5613–5620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, A.A.; Khan, U.S.; Awan, A.U.; Hamza, A. Tracking Control and Backlash Compensation in an Inverted Pendulum with Switched-Mode PID Controllers. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, A.A.; Khan, U.S. Compensation of Backlash for High Precision Tracking Control of Inverted Pendulum by Drive-Anti Drive Mechanisms. Eng. Proc. 2024, 75, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, Z.; Habib, F.; Mukhtar, M.H.; Munawar, K. Design, Control and Implementation of 2-DOF Motion Tracking Platform using Drive-Anti Drive Mechanism for Compensation of Backlash. In Proceedings of the 2007 International Workshop on Robotic and Sensors Environments, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 12–13 October 2007; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, A.A.; Malik, M.B. Robust current-mode dc drive. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Colloquium (IAPEC), Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 18–19 April 2011; pp. 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).