Abstract

In agricultural workplaces, upper-body strain arises not only from lifting and carrying harvest crates but also from pushing, pulling, twisting, and squatting motions. Drawing inspiration from the momentary shoulder contraction and whole-body coordination characteristic of traditional Japanese martial arts, this study proposes a method for “moving efficiently with minimal exertion” across multiple task actions, specifically, lateral pushing, fore-aft pulling, and trunk rotation. Each action is modeled as a control system, and mechanical-engineering simulations are employed to derive optimal muscle-output patterns. Simulation results indicate that peak muscular force can be lowered compared with conventional techniques. A simple physical test rig confirms the load-reduction effect, showing decreases in both perceived exertion and electromyographic activity. These findings offer practical knowledge that can be immediately applied not only to agriculture but also to logistics, nursing care, and other settings involving repetitive handling of heavy objects or machine operations.

1. Introduction

Due to declining birth rates, an aging population, and the rising average age of workers, the agricultural sector is facing a serious shortage of successors. This is a global trend, and particularly in Japan, statistics from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries show that the average age of agricultural workers exceeds 65 years, with further aging expected in the future. Agricultural work often involves lifting and lowering heavy objects such as containers during harvesting, which is not easy even for young people and imposes an extremely heavy physical burden on the elderly.

To improve such circumstances, in recent years, including in the field of long-term care, the development of power-assist support devices that help with lifting and transporting loads has progressed. For example, Yoshimitsu and Yamamoto proposed support clothing equipped with motors [1], and Shiraishi et al. developed a mechanism that enables lifting and holding heavy objects using mainly the strength of the thighs, without requiring much energy [2]. These devices do not reduce the actual load but have been confirmed to provide psychological and mechanical effects that make the load feel lighter to the user by supporting it with the shoulders [3,4,5].

In addition, it has been reported that practitioners of traditional Japanese martial arts are capable of lifting weights equivalent to twice their own body weight at most, even at an advanced age. This is considered to be based not only on techniques that move the body efficiently, but also on the use of latent muscular and nervous system capabilities inherent in humans [6,7]. Studies analyzing such physical movements from the perspectives of biomechanics and control engineering have also been continuously conducted [8,9,10], forming a technical foundation to support labor sustainability across generations.

In the modern age, such labor support methods are largely dependent on mechanical drive systems. However, this study aims to return to human-powered systems and reconstruct a simple lifting method that utilizes the fundamental motor abilities of living beings. In other words, this study holds significance not only in reducing work burden in agricultural settings, but also from a welfare perspective in maintaining health and extending the longevity of the elderly.

2. Methods

Simulation of Lifting Techniques in Traditional Martial Arts

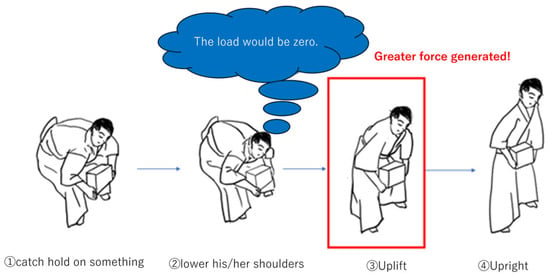

In traditional Japanese martial arts, the object lifting motion is not merely based on muscle strength but involves inducing a change in the center of gravity by temporarily lowering the shoulders to give the illusion of reduced load. Figure 1 shows the concept of this lifting method. In this technique, the object is supported using the lower body first, then the shoulders are temporarily contracted to make the downward force seem smaller. Returning to the original posture immediately afterward applies an apparently larger upward force on the object.

Figure 1.

Concept of traditional martial arts lifting technique.

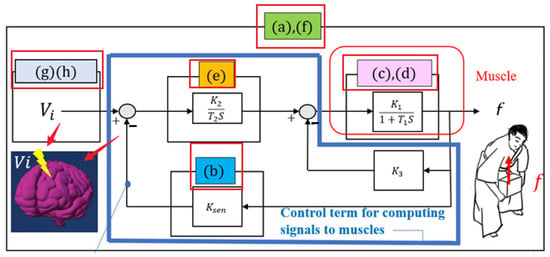

In the block diagrams of this study (Figure 2 and Figure 3), the input signal represents the motor command signal sent from the brain to the muscles, while the output f represents the actual generated muscle force or muscle output. Among the control parameters, the proportional gain corresponds to the muscle’s output capacity or physical strength, and the time constant T1 indicates the inherent response delay of the muscles and joints. The integral gain corresponds to the speed of signal transmission and processing from the brain to the muscles. The feedback gain represents the sensory feedback of the load; setting this value to zero temporarily simulates the state of “relaxation” (loss of load sensation) used in traditional martial arts.

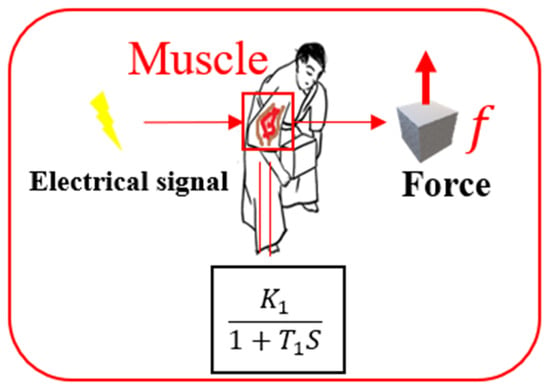

A similar principle is seen in weightlifting, where athletes momentarily release the object from the shoulders before lifting it again, gaining greater muscle output. To analyze such body movement using control engineering, this study models the process from the motor command signal Vi (input) from the brain to muscle output f (output) as a first-order lag transfer function (Figure 2). Figure 3 extracts only the muscle-related part from Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Block diagram from Vi to f.

Figure 3.

Block diagram of muscle portion.

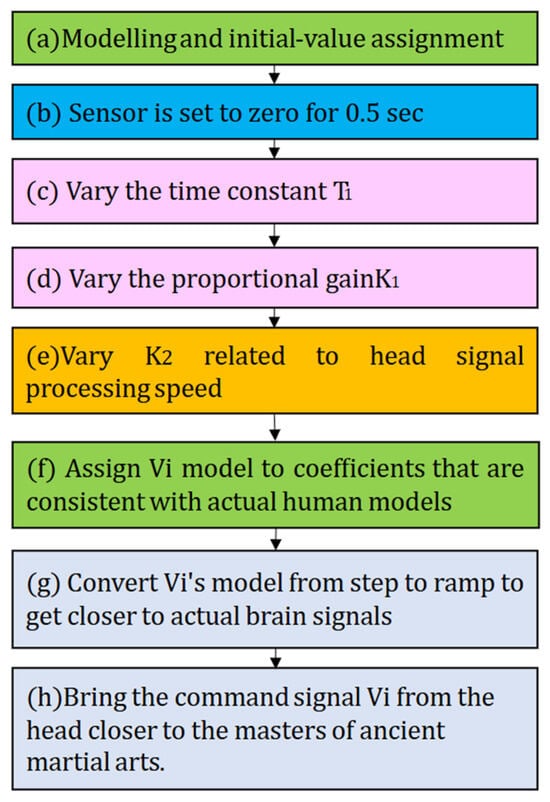

Various parameters (e.g., time constant , proportional gain , integral term ) are adjusted in these simulations to evaluate their effect on muscle output (Table 1).

Table 1.

Explanation of the 8 simulation steps (a)–(h).

In this study, the muscle output f is modeled as a first-order lag system, expressing the relationship between command signals and muscle output. To increase output, K1 must be high, and to enhance response speed, T1 must be small. Since damping and oscillation are not considered, a simpler first-order model is used instead of a second-order system. The control system is the integral–proportional (IP) control for balancing responsiveness and stability. To minimize deviation from the target during object holding, integral control is essential.

The integral gain implies faster command transmission from the brain to muscles. Feedback gain is introduced to compare the muscle output with the brain signal. In traditional martial arts, techniques that make muscles feel as if the load has been removed allow efficient lifting. This is modeled by setting = 0, effectively blocking feedback and simulating a state where no load is felt. Though the actual load is never zero, this assumption helps clearly visualize the principle in the model.

3. Results

3.1. General Definition of Simulation Plots and Parameters

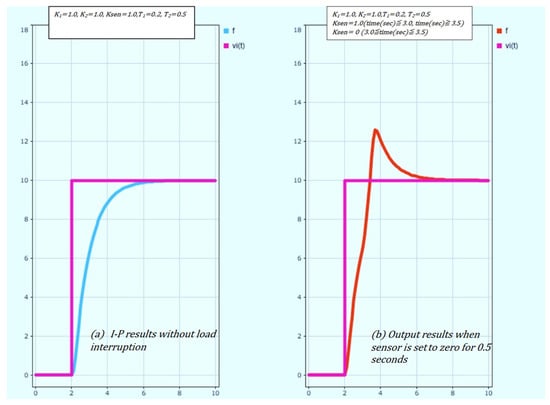

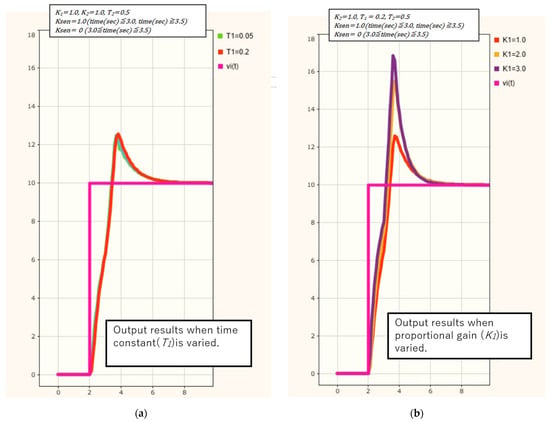

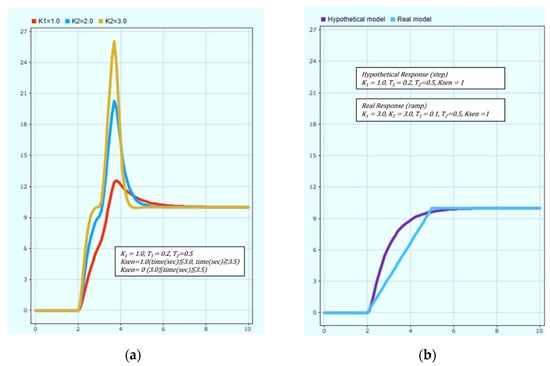

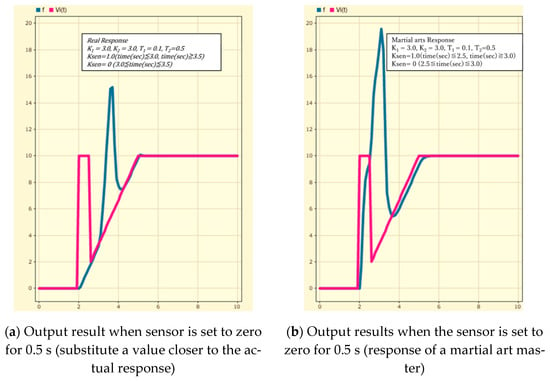

In Section 3.2, Section 3.3, Section 3.4 and Section 3.5, which show the simulation results, the pink line () indicates the target input signal from the brain, applied as either a step or ramp command. In contrast, the lines shown in blue, red, or yellow represent the resulting muscle output f calculated under various parameter conditions. The different colors observed in Figure 4 in Section 3.2, Figure 5 in Section 3.2 and Figure 6 in Section 3.4 are used to compare the influence of varying specific parameters, such as the time constant or gains (, ), on muscle responsiveness and peak force. The sharp rise (spike) in the output line f within the graphs visually illustrates the principle of force amplification caused by the temporary blocking of feedback . Figure 7 in Section 3.5 shows the eight steps (a to h) to derive the maximum output f using this model. Figure 8 in Section 3.5 compares the response intervals of a martial arts master with those of typical response patterns.

3.2. Influence of Temporary Blocking of Feedback Ksen

Figure 4 shows how the output changed when feedback was set versus when it was not set. It can be seen that setting feedback for 0.5 s resulted in an output value 1.2 times greater than when feedback was not set. Figure 5a shows the simulation result for a basic lifting movement conducted without blocking feedback. The input signal (pink line) represents the brain command to the muscles and transitions from 0 to 10 in a step change over 2 s. In this case, the output signal aligns with the input, maintaining functional force feedback. Next, the simulation was conducted under the condition where was set to 0 between 3.0 and 3.5 s to temporarily block feedback. Figure 5b illustrates that during the 0.5-s feedback block, the integrator continued accumulating deviation signals, leading to a muscle output of about 13, which exceeds the normal value of 10. After feedback resumed, the output gradually returned to its original value.

This result shows that the spike in muscle output is not due to increased input signals, but caused by the temporary blocking of feedback, aligning with the mechanism of enhanced output through “relaxation” in traditional martial arts.

Figure 4.

(a) Output f without feedback block; (b) Output f when feedback is set to zero for 0.5 s.

Figure 5.

(a) Output results when varying T1; (b) Output results when varying K1.

3.3. Influence of Time Constant T1

The effect of changing the time constant T1 in the first-order system was evaluated. As shown in Figure 5a, output comparisons were made for T1 values of 0.2, 0.1, and 0.05 s. Although response speed improved with a smaller T1, the total amount of deviation signal accumulated in the integrator remained unchanged, leading to no significant difference in final muscle output. This indicates that improving response speed alone does not contribute to increased output.

3.4. Influence of Proportional Gain K1

Next, the proportional gain K1, representing the muscle’s output capacity, was varied at values 1, 2, and 3 (Figure 5b). Higher K1 values resulted in greater output for the same input, meaning stronger muscles yield higher output. However, doubling or tripling muscle size requires long-term training, suggesting that optimizing neural control may be a more practical approach.

The effect of varying the signal processing speed K2/T2 from the brain to muscles was evaluated. Figure 6a shows results for K2 values of 1, 2, and 3. Larger K2 values led to increased deviation accumulation in the integrator, significantly increasing muscle output. This suggests that improving neural transmission speed can dramatically enhance muscle force, supporting the idea that quick neural responses underlie explosive strength in martial arts.

Figure 6.

(a) Output results when varying K2; (b) Comparison of hypothetical and real response model.

3.5. Parameter Settings Aligned with Human Behavior

To better reflect real human brain signals, the input Vi was changed from a step to a ramp, K1 and K2 were increased, and T1 was reduced. Figure 8a shows the effect of changing Vi from a step to a ramp. With improved model responsiveness, the final output f reached 15 in response to an input Vi = 10. This confirms that smoother input combined with high responsiveness effectively maximizes muscle output. Figure 8a shows the result when Ksen was set to 0 between 3.0 and 3.5 s under ramp input. Figure 8b shows the result when Ksen was set to 0 between 2.5 and 3.0 s under ramp input. The integrator accumulated signals, causing a sharp increase in output. This corresponds to martial arts techniques where the body is momentarily relaxed to produce a burst of power. The simulation confirmed that outputs up to twice the input were possible, providing a scientific explanation for traditional techniques.

Figure 7.

Steps for deriving maximum f.

Figure 8.

(a) close to actual response; (b) feedback block mimicking martial arts.

4. Conclusions

We analyzed energy-efficient lifting techniques based on shoulder contraction in traditional martial arts using control theory. It demonstrated that strength amplification is possible through optimization of neural response rather than muscle strength.

Greater output was achieved by increasing the brain-to-muscle signal transmission speed (K2), rather than muscle mass. Temporary relaxation in martial arts corresponds to blocking feedback, causing brain signals to accumulate and amplify force. Experiment results showed higher output with shorter conscious relaxation times, matching simulation results. Feedforward control improved response time and enabled immediate action.

The proposed “moving method efficiently with minimal exertion” offers potential to reduce physical burden for elderly agricultural workers. Daily tasks like lifting crops or farm equipment are demanding and pose excessive strain on seniors when using traditional strength-based methods. By focusing on motor commands and muscle control properties, this method enables efficient force output without relying on physical strength. This helps agricultural workers use their full physical potential while reducing fatigue and injury risk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S. (Hajime Shiraishi); methodology, T.S.; software, H.S. (Haruhiro Shiraishi); validation, H.S. (Hajime Shiraishi) and T.S.; formal analysis, M.I.; investigation, M.I.; resources, H.S. (Hajime Shiraishi); data curation, H.S. (Haruhiro Shiraishi); writing—original draft preparation, H.S. (Haruhiro Shiraishi); writing—review and editing, H.S. (Haruhiro Shiraishi); visualization, H.S. (Haruhiro Shiraishi); supervision, H.S. (Hajime Shiraishi); project administration, H.S. (Hajime Shiraishi). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Tetsuji Shimogawa of the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Fukuoka University for constructing the experimental apparatus, and to Akiko Shiraishi for her creation of the illustrations depicting traditional martial arts. We are also deeply grateful to Hideaki Shoji of the National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Resilience for his valuable advice regarding the versatility of application.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yoshimitsu, T.; Yamamoto, K. Development of a power assist suit for nursing work. In Proceedings of the SICE 2004 Annual Conference, Sapporo, Japan, 4–6 August 2004; Volume 577. [Google Scholar]

- Shiraishi, H.; Shiraishi, H.; Sakaki, T.; Iwamura, M. Development of Load-lifting-assist Mechanism Using Lower Limbs. Sens. Mater. 2024, 36, 2045–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, K.-W.; Chung, H.-J.; Jung, E.-J.; Kang, J.-S.; Son, S.-E.; Yi, H. Development of Shoulder Muscle-Assistive Wearable Device for Work in Unstructured Postures. Machines 2023, 11, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Pan, C.; Wei, L.; Bahreinizad, H.; Chowdhury, S.; Ning, X.; Santos, F. Shoulder-assist exoskeleton effects on balance and muscle activity during a block-laying task on a simulated mast climber. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2024, 104, 103652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, M.; Mason, G.; Niewolny, K. Assistive Technologies for Upper Extremity Mobility on the Farm. Va. Coop. Ext. 2021. Available online: https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/ALCE/ALCE-260/ALCE-260.html (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Watanabe, Y.; Sakaguchi, Y. Effects of a Body Manipulation of Japanese Martial Arts on Standing Balance. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieger, B.; Wilczyński, B.; Sztuka, B.; Biały, M.; Zorena, K. Humeral Retroversion, Shoulder Range of Motion, and Functional Mobility in Striking Martial Arts Athletes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 78369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z. High-precision Angle Adaptive Control Simulation of Synchronous Motor for Automatic Lifting. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 30742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Qu, X.; Chen, C.-H. Simulation of lifting motions using a novel multi-objective optimization approach. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2016, 53, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Ouyang, M.; Gong, J.; Liu, G. Mechanical Simulation and Installation Position Optimisation of a Lifting Cylinder. IET J. Eng. 2019, 2019, 74–78. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).