Abstract

In this study, we emphasize that the maximum sum rate can be achieved through AI-based subchannel allocation, while taking into account all users’ quality of service (QoS) requirements in data rates for hybrid beamforming systems. We assume a limited number of radio frequency (RF) chains in practical hybrid beamforming architectures. This constraint makes subchannel allocation a critical aspect of hybrid beamforming in massive multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) systems with orthogonal frequency division multiple access (MIMO-OFDMA), as it enables the system to serve more users within a single time slot. Unlike conventional subcarrier allocation methods, we employ a deep reinforcement learning (DRL)-based algorithm to address real-time decision-making challenges. Specifically, we propose a dueling double deep Q-network (Dueling-DDQN) to implement dynamic subchannel allocation. Simulation results demonstrate that the performance of the proposed algorithm gradually approaches that of the greedy method. Furthermore, both the average sum rate and the average spectral efficiency per user improve with a reasonable variation in outage probability.

1. Introduction

To meet users’ requirements, millimeter-wave (mmWave) technology, operating in the 30 to 300 GHz frequency band, has emerged as a promising candidate and has been widely discussed in 5G communication systems [1,2]. However, due to its high carrier frequency, mmWave signals suffer from severe path loss. Fortunately, the short wavelength of mmWave allows for dense antenna array configurations within a limited physical space. This enables significant beamforming gain through large antenna arrays, which can compensate for the high path loss [3,4,5], making massive multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) an attractive solution for mmWave systems.

Traditional MIMO systems typically employ a fully digital architecture at the baseband for beamforming. While effective, this approach is power-hungry and costly, particaularly for massive MIMO and mmWave systems, as it requires a dedicated radio frequency (RF) chain for each antenna element [6]. To address this issue, hybrid beamforming architectures have been proposed [7,8].

As previously mentioned, the limited bandwidth must be shared among multiple users. To enhance data rates in wireless communication, orthogonal frequency division multiple access (OFDMA) combined with space division multiple access (SDMA) has been proposed [9]. OFDMA with hybrid beamforming systems can select the optimal set of users to serve within the same resource block (RB) and adjust beamforming weight vectors to minimize interference among users sharing the same subcarrier.

Undoubtedly, optimizing resource allocation across frequency, space, and time is a highly complex problem. To tackle this, various AI-based approaches have been explored. However, implementing real-time subchannel allocation in complex communication systems remains an open challenge. Motivated by the capabilities of AI, we propose an AI-based approach to solve the dynamic subchannel allocation problem. Specifically, we employ a deep reinforcement learning (DRL) algorithm to handle subchannel scheduling in a massive MIMO-OFDMA system with hybrid beamforming, aiming to maximize the overall data rate while also satisfying each user’s quality of service (QoS) requirements. Nevertheless, designing an appropriate network architecture and tuning hyperparameters to suit the specific scenario remains a significant challenge.

2. System Model

In the downlink of an mmWave and large-scale MIMO-OFDMA system with a fully connected hybrid beamforming design for a frequency-selective channel, we consider that base station (BS) equips antennas and RF chains. BS transmits data streams simultaneously at each subcarrier [10,11]. The total number of subcarriers is denoted by . Moreover, a total of users are served in each time slot, with each user equipped with a single antenna. The number of RF chains cannot exceed the number of transceiver antennas, i.e., , and . We assume that the number of scheduled users per resource block (RB) is equal to , and these users are selected from the total user set , i.e., . Let denote the set of users scheduled in the RB, where , and is . Furthermore, all N users must be served in at least one RB per time slot. Therefore, in our simulation setup, we assume that , with the hybrid beamforming structure employed at the transmitter and single-antenna multi-user terminals at the receiver.

Although subchannel allocation is implemented in units of RBs indexed by k, the digital precoder is designed for each subcarrier. At each subcarrier k, where , data symbols are first processed by a low-dimensional digital precoder . The digitally precoded signals are then transformed into the time domain using -point inverse fast Fourier transforms (IFFTs). After this, cyclic prefixes (CPs) are added to each stream to mitigate inter-symbol interference (ISI). Following the CP addition, the signal is passed through a high-dimensional analog precoder . In a fully connected structure, each RF chain is connected to all antennas via phase shifters. Since the analog precoder operates in the time domain, it remains identical across all subcarriers. Finally, the transmitted signal at subcarrier k is expressed as:

where represent the combined data symbols for served users at the subcarrier/RB. We assume that the total transmit power is equally divided among each symbol as ; is the data symbol of user in at the subcarrier/RB . Next, is the digital precoder matrix at the subcarrier/RB for served users, and is the digital precoder for the user . The received signal for the user at the subcarrier/RB is given by

where and are the additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) and the channel vector at the subcarrier for user , respectively.

The main goal of this paper is to maximize the sum rate while considering the Quality of Service (QoS) for each user’s data rate through dynamic subcarrier/RB allocation. The problem formulation can be expressed as:

where (3b) represents the hardware constraint ensuring that each column of the analog precoder has unit norm, and . Equation (3c) is the transmit power budget constraint for each subcarrier and user, and is the data rate constraint for each user in (3d). In (3a), it is important to note that and are designed as in [12]. Furthermore, denotes the data rate for user at subcarrier , and the rate can be expressed as

where is the subcarrier spacing (SCS). In the subchannel allocation strategy for maximizing the sum rate under deep fading, we define the outage probability as follows.

where is the number of users whose achievable data rates fall below the target constraint at the slot .

3. Dynamic Subchannel Allocation with DRL-Based Method

We define the states, actions, rewards, and next states for our proposed method. The downlink transmissions are organized into frames of 10 ms, and each frame contains 10 subframes [13].

- States (): In the proposed algorithm, is a set that combines different meaningful vectors or scalars, with time-variant feature data as the input to the network. We define , where , and represents the path loss of the user at the time slot. Here, we assume that the path loss does not change at all time slots at an episode for each user, and each user’s path loss is only updated at the beginning of the next episode. Next, is the vector representing each user’s channel state, where . We preprocess channel gain for all subcarriers of each user before inputting them into the neural network. is computed by the following equation

- Actions (): We treat each possible subchannel assignment as an action and implement the allocation at each time slot. For partial allocation, we randomly generate some allocation cases as an action set, without considering all possible subchannel allocations. For full allocation, the action set includes all possible subchannel allocation solutions. According to [13], RB consists of 12 consecutive subcarriers in the frequency domain. For simplicity in this simulation, we assume that each RB group (RBG) contains only one RB, rather than multiple RBs, as defined in the specification. We assume that each user in the set is served at least one RB in each time slot. Therefore, we eliminate the options where a user is not allocated any RBs. In summary, we represent as a number corresponding to a bitmap that indicates the subchannel allocation, and the agent selects based on the current at each time slot .

- Rewards (): We define a reward function to guide the agent, rewarding correct actions and penalizing irregular ones. The agent’s goal is to maximize the long-term expected cumulative reward. The reward function is expressed as:

Dueling-DDQN Algorithm and Network Structure

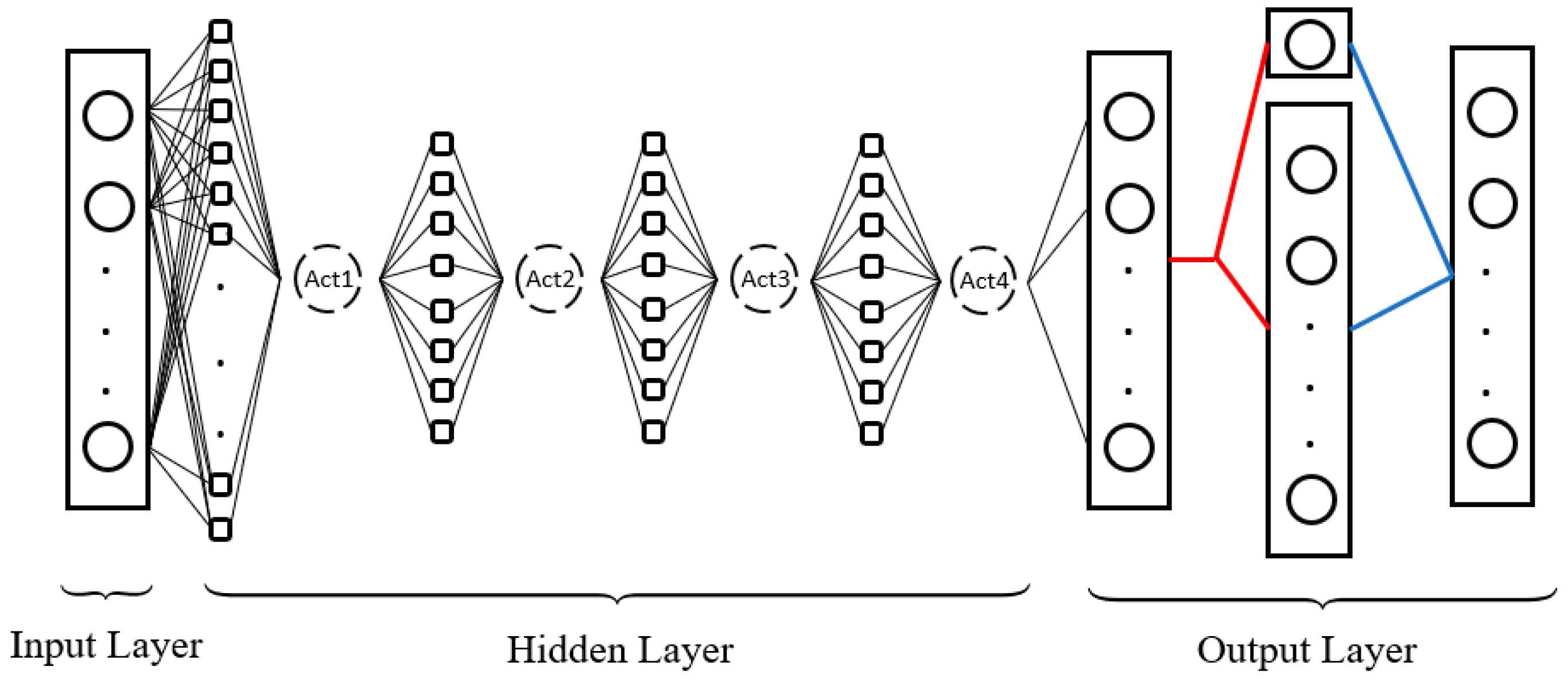

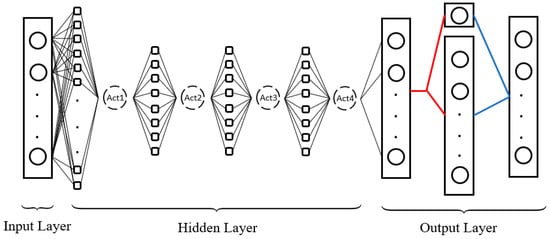

In the proposed Dueling-DDQN structure, the weights and biases of the neural network are updated via backpropagation (BP) to minimize the loss value in the loss function. The specific structure of the proposed Dueling-DDQN is shown in Figure 1, where “Act” is an activation function. The activation function used is the rectified linear unit (ReLU). The number of outputs corresponds to the size of the action set, and each output represents the expected cumulative reward for that action.

Figure 1.

Neural network structure of the proposed Dueling-DDQN.

The output layer of the Dueling-DDQN has two streams: one for estimating the state value (a scalar) and another for estimating the advantages of each action. The blue line in Figure 1 combines these two streams using the following equation:

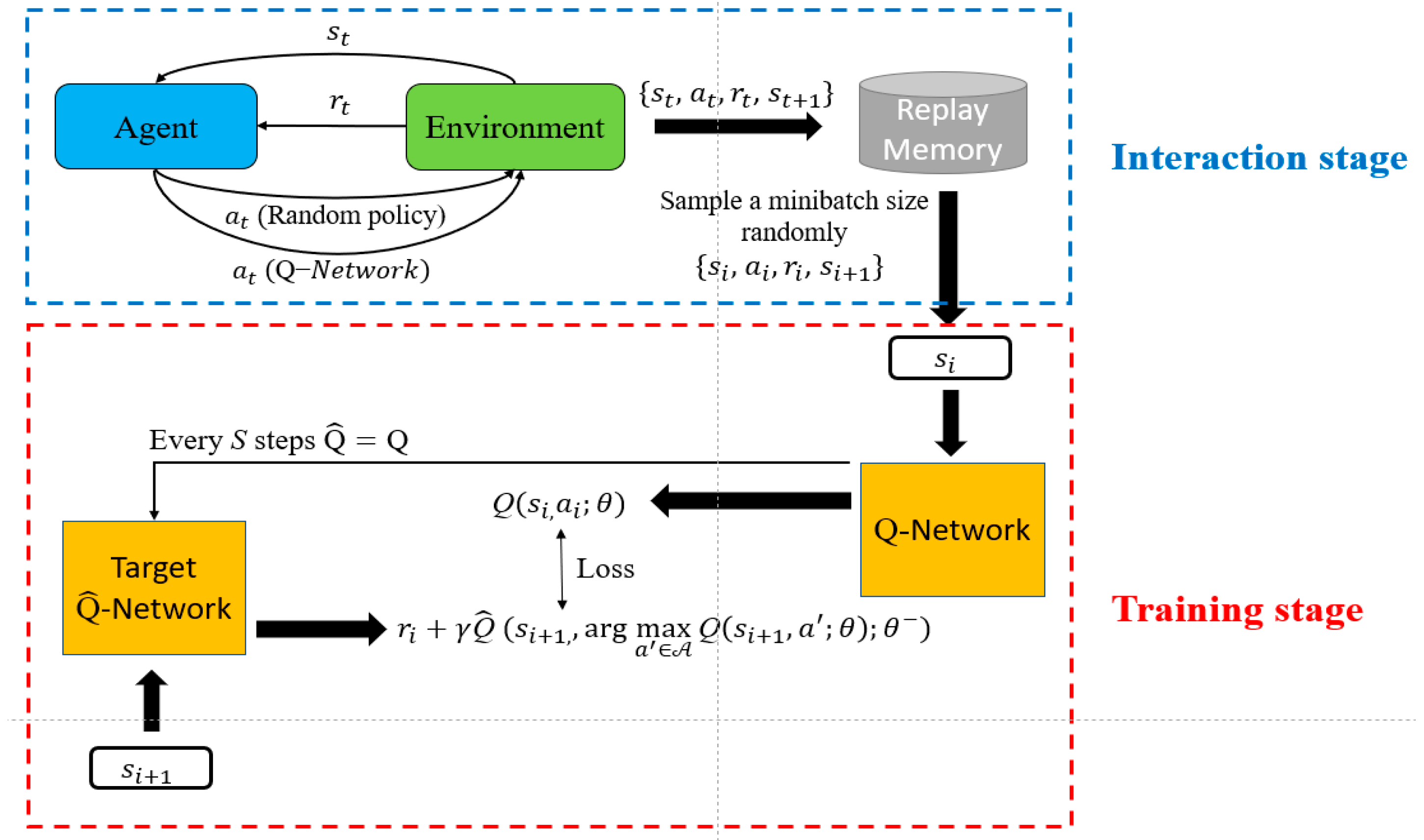

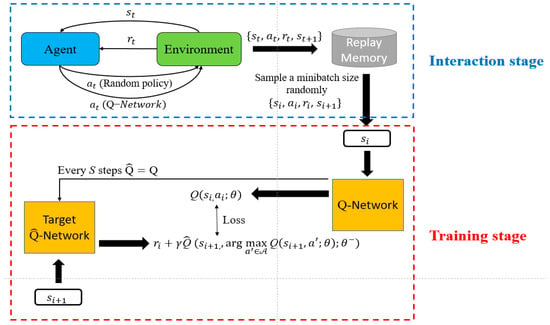

where estimates the state-value and its output is a scalar, and estimates the advantages for each action, and its output is a vector whose size is the same as the action set. Further, is the parameter of the Q-network, and is the total number of actions. The specific process of the complete model is shown in Figure 2. Due to limited space, we omit the detailed discussions.

Figure 2.

Workflow of Dueling-DDQN algorithm.

For the hybrid beamforming design, we apply the signal-to-leakage-plus-noise ratio (SLNR) approach, which is commonly used in MU-MIMO beamformer design to mitigate the challenges of non-convex design problems [12]. We use the SLNR method to design an analog precoder and the zero-forcing (ZF) method to design a digital precoder. Due to space constraints, we also omit the details of this part, which will be discussed in the full version of the journal paper.

4. Simulation Results

The bandwidth part (BWP) size refers to the number of Resource Blocks (RBs) for a given bandwidth range, while the RBG size represents the number of RBs in a group. We assume a subcarrier spacing (SCS) of 60 kHz, as this value is suitable for both frequency range 1 (FR1) and frequency range 2 (FR2) [14]. Additionally, subchannel allocation is performed at each time slot, with a total of 40 slots in one radio frame. The environment is modeled with two clusters and ten rays, where each cluster has an angular spread of 10 degrees, and the cluster angle range is [0, 2π). The path loss for the user is generated using the Non-Line of Sight (NLOS) urban microcell (UMi)-Street Canyon scenario described in [15]. In the numerical simulation, unless otherwise mentioned in the article, the following experiments are used , , , and .

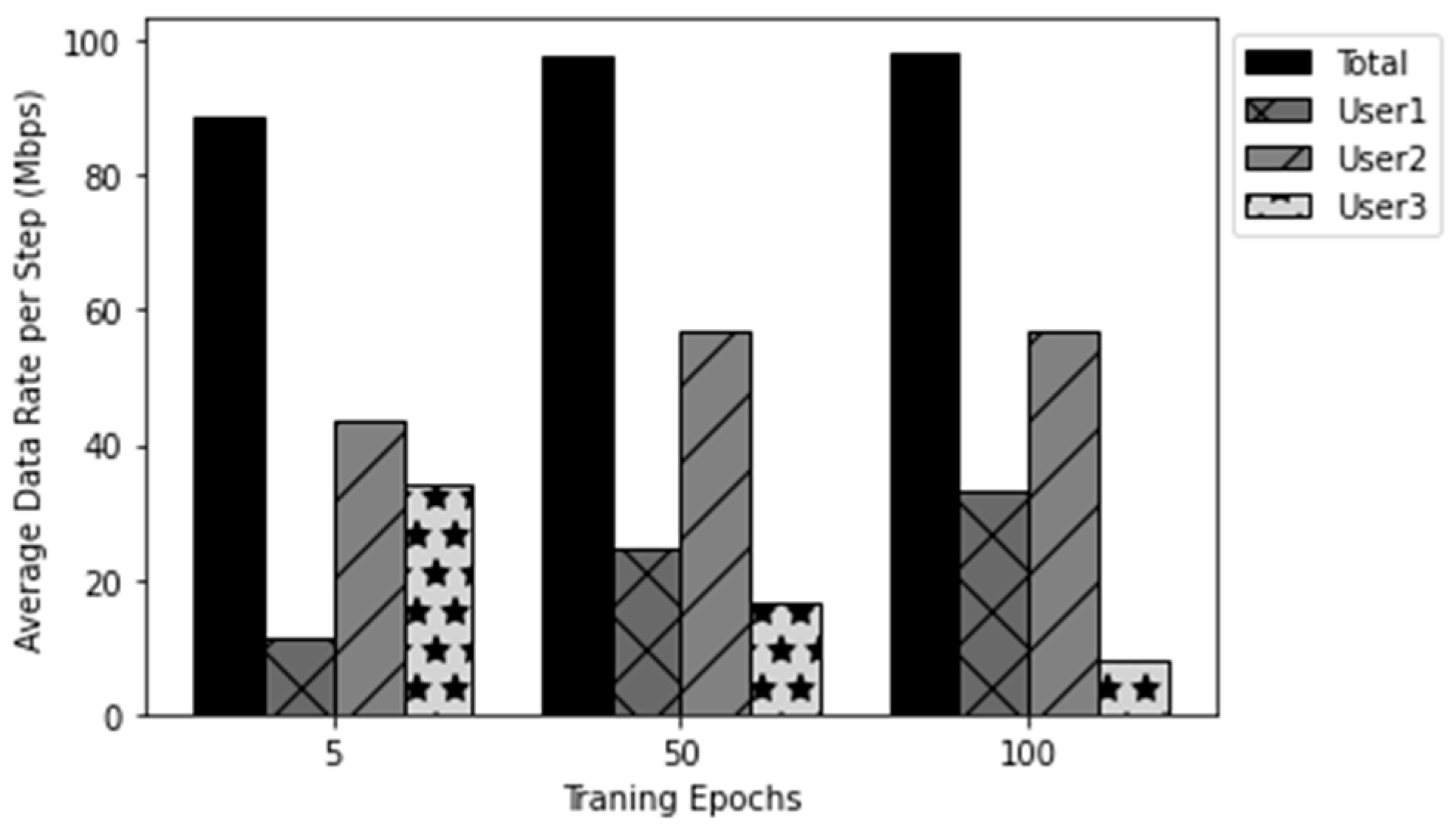

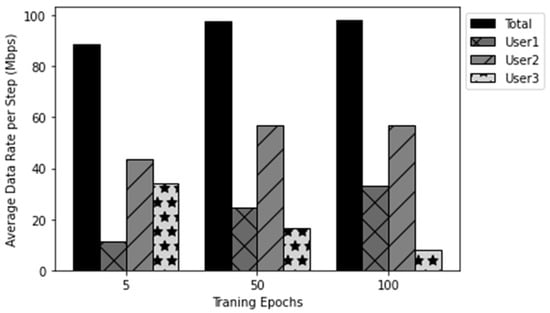

Figure 3 illustrates the average data rate based on the agent’s policy in a fixed path loss environment. The average data rate for each user is computed for one episode, i.e., one radio frame. In this experiment, a random episode is selected from the testing data, and this selection is fixed for each test, as previously mentioned. The testing results are recorded after 5, 50, and 100 training epochs. As shown in Figure 3, the sum rate increases as the training steps progress for the observed episode. However, this allocation may slightly increase the outage probability, as the spectrum resources available to disadvantaged users may not be sufficient to meet their data rate constraints. Even when the policy allocates most of the subchannels to these users, they may still fail to achieve the required data rate in some cases. As a result, the agent prioritizes increasing spectral efficiency to raise the sum rate, rather than allocating most resources to disadvantaged users.

Figure 3.

Comparison among all the users’ testing performance after different training epochs in the fixed path loss value case.

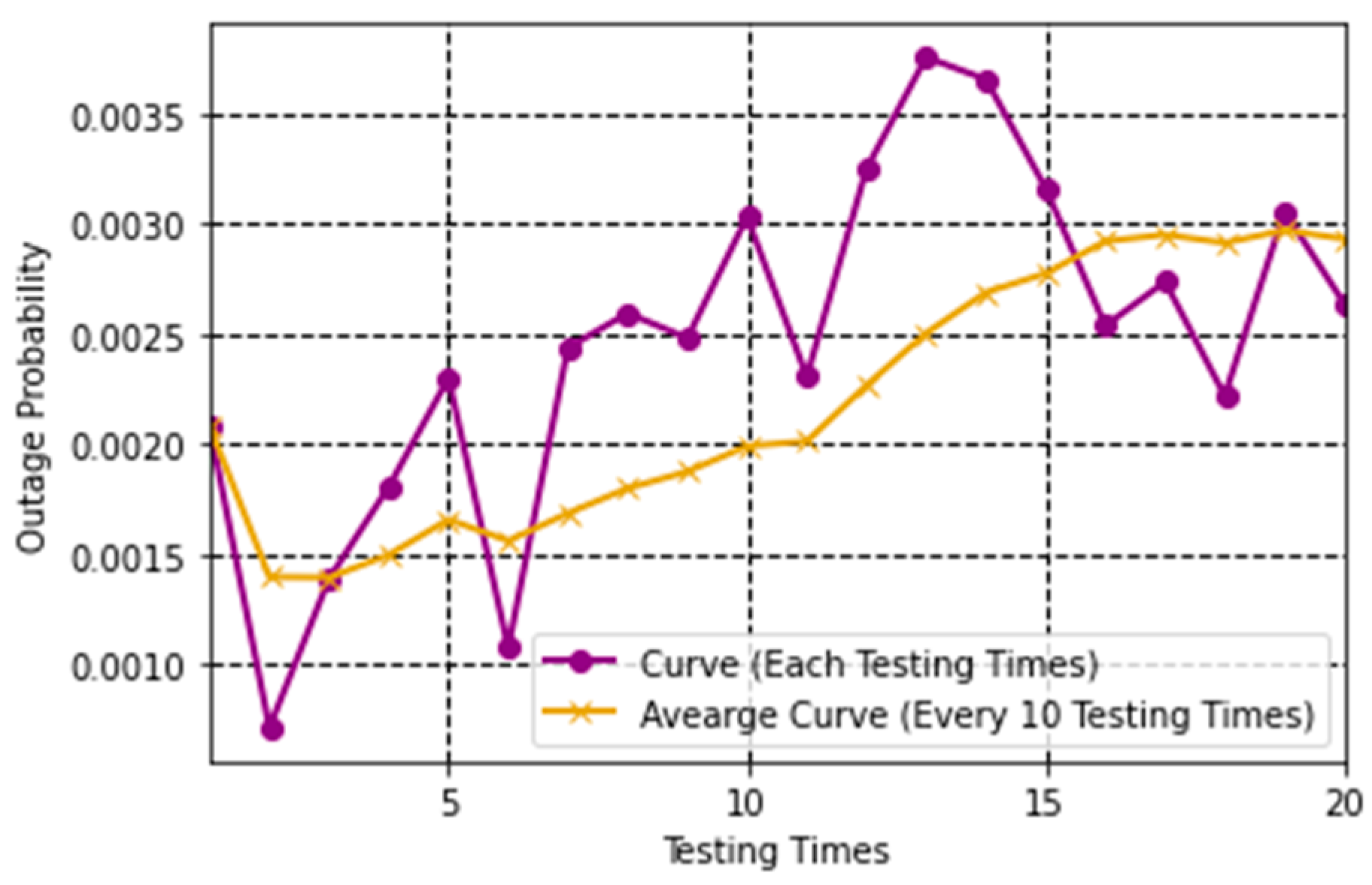

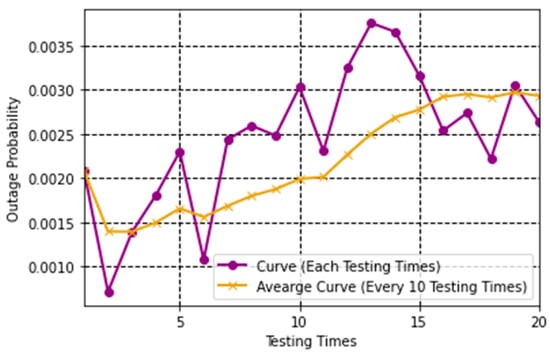

The outage probability during testing is shown in Figure 4, where each circular marker on the curve represents the outage probability for a specific testing time. The average curve is computed by averaging the outage probabilities from every 10 testing times. It should be noted that the experiments shown in Figure 3 focus on a single radio frame’s state. To demonstrate the stable performance of the proposed algorithm, we test the well-trained network on identical testing data.

Figure 4.

Outage probability of the proposed algorithm in testing.

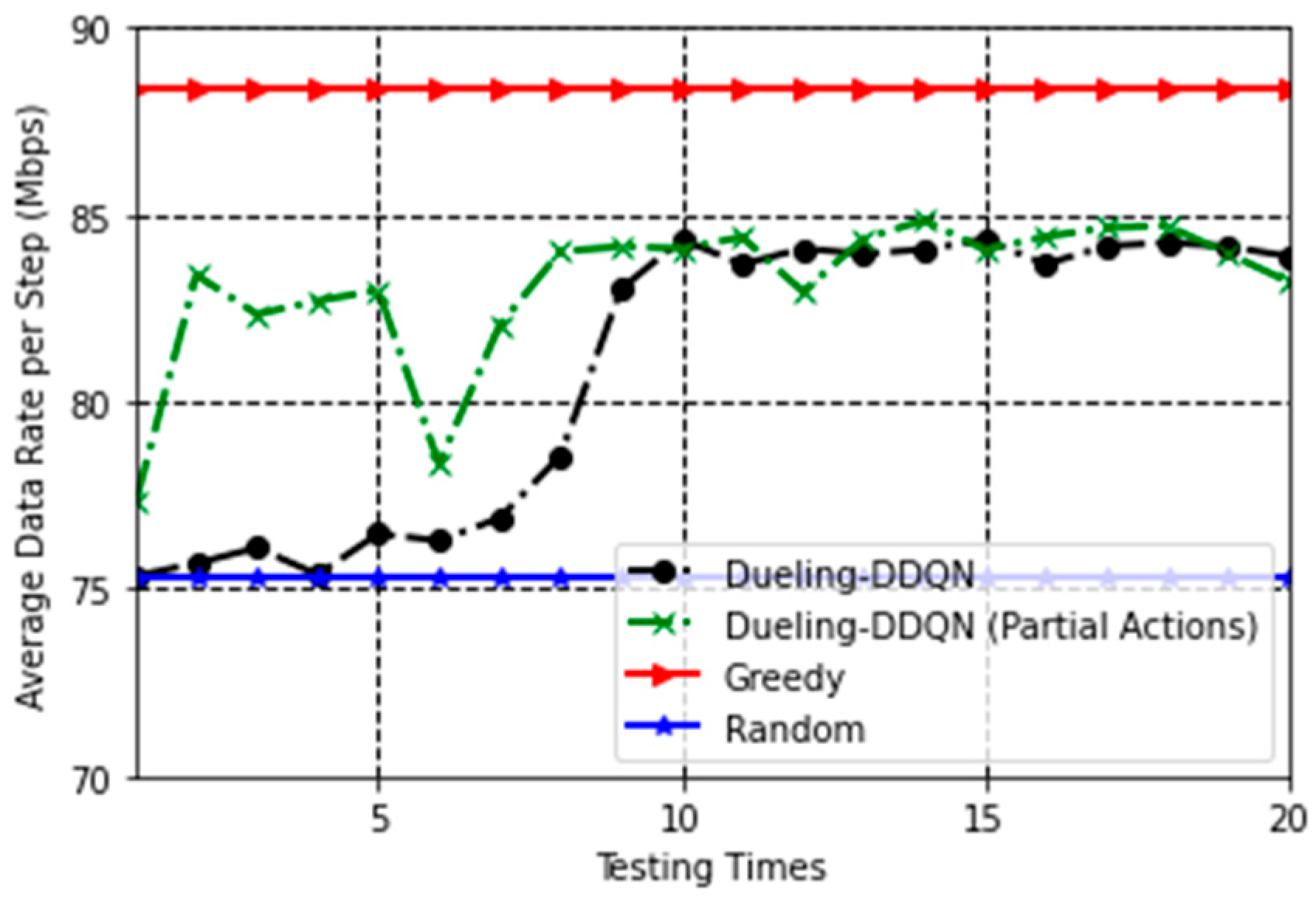

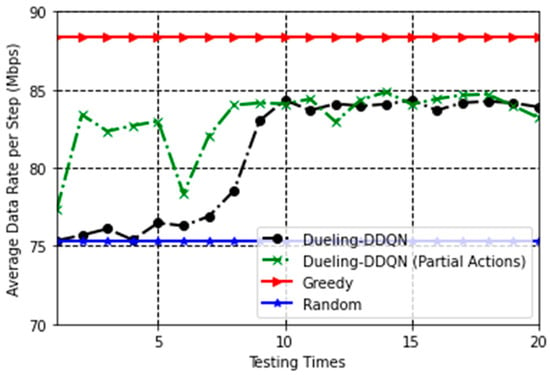

The performance of the proposed algorithm and the compared methods is shown in Figure 5. The greedy line and the random line are computed over the testing set. The greedy method tests all subchannel allocations and selects the action that avoids outage. It then chooses the action that results in the highest sum rate from the non-outaging actions. In contrast, the random method randomly selects an action from all possible actions. If the channel state is suboptimal and none of the allocations can meet each user’s QoS in a radio frame, the greedy-allocation method selects an action from the ineligible options, while the random-allocation method picks an action at random. Similarly, for both methods, the channel parameters vary with testing steps, though the path loss values remain fixed. As observed, the performance of the partial allocation method is comparable to that of the full allocation method, with both curves closely matching the greedy line after training on the testing set. This suggests that the algorithm is capable of handling large subchannel allocations in real-world scenarios and demonstrates good generalization.

Figure 5.

Testing curve of different methods in average data rate.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we consider the hybrid beamforming and the subchannel allocation with the AI-based algorithm for the mmWave massive MIMO-OFDMA systems. The simulation results verify that our proposed algorithm can gradually approach the performance of the greedy allocation in testing for both architectures. Moreover, stability and generalization are also shown in the results. Additionally, we try both cases of full assignment and partial assignment for subchannel allocation, which shows that the performance of the proposed algorithm could achieve the same effect as long as we consider some parts of all the assignments as actions. Finally, compared to the different scenes, we refer that the subchannel allocation with the Dueling-DDQN algorithm could be applied to the practical mmWave and massive MIMO-OFDMA with hybrid beamforming.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-F.C.; methodology, J.-W.L. and Y.-F.C.; software, J.-W.L.; validation, J.-W.L. and Y.-F.C.; formal analysis, J.-W.L.; investigation, J.-W.L.; resources, J.-W.L. and Y.-F.C.; data curation, Y.-F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-W.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.-F.C.; visualization, J.-W.L.; supervision, Y.-F.C.; project administration, Y.-F.C.; funding acquisition, Y.-F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, R.O.C., under Grant NSTC 114-2221-E-008-057.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are generated through computer simulations. The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Andrews, J.G.; Buzzi, S.; Choi, W.; Hanly, S.V.; Lozano, A.; Soong, A.C.K. What Will 5G Be? IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2014, 32, 1065–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, T.S.; Sun, S.; Mayzus, R.; Zhao, H.; Azar, Y.; Wang, K. Millimeter Wave Mobile Communications for 5G Cellular: It Will Work! IEEE Access 2013, 1, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseini, S.A.; Ding, M.; Hassan, M. Massive MIMO performance comparison of beamforming and multiplexing in the Terahertz band. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), Singapore, 4–8 December 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Swindlehurst, A.; Ayanoglu, E.; Heydari, P.; Capolino, F. Millimeter-wave massive MIMO: The next wireless revolution? IEEE Commun. Mag. 2014, 52, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Li, G.Y.; Swindlehurst, A.L.; Ashikhmin, A.; Zhang, R. An Overview of Massive MIMO: Benefits and Challenges. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2014, 8, 742–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogale, T.E.; Le, L.B.; Haghighat, A.; Vandendorpe, L. On the number of RF chains and phase shifters, and scheduling design with hybrid analog–digital beamforming. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2016, 15, 3311–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, X.; Letaief, K.B. Hybrid Beamforming for 5G and Beyond Millimeter-Wave Systems: A Holistic View. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2020, 1, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molisch, A.F.; Ratnam, V.V.; Han, S.; Li, Z.; Le Hong Nguyen, S.; Li, L. Hybrid beamforming for massive MIMO: A survey. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2017, 55, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, T.F.; Klein, A. A resource allocation strategy for SDMA/OFDMA systems. In Proceedings of the 2007 16th IST Mobile and Wireless Communications Summit, Budapest, Hungary, 1–5 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, H.-H.; Chen, Y.F.; Tseng, S.-M. Hybrid Beamforming and Resource Allocation Designs for mmWave Multi-User Massive MIMO-OFDM Systems on Uplink. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 133070–133085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.Y.; Chen, Y.F.; Tseng, S.M. Hybrid Beamforming and Data Stream Allocation Algorithms for Power Minimization in Multi-User Massive MIMO-OFDM Systems. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 101898–101912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, V.N.; Nguyen, D.H.N.; Frigon, J. Subchannel allocation and hybrid precoding in millimeter-wave OFDMA systems. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2018, 17, 5900–5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3GPP Technical Specification 38.211 v15.2.0, Physical channels and modulation (Release 15), 2018. Available online: https://www.3gpp.org/ftp/Specs/archive/38_series/38.211/. (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- 3GPP Technical Specification 38.104 v16.5.0, Base Station (BS) radio transmission and reception (Release 16), 2020. Available online: https://www.3gpp.org/ftp/Specs/archive/38_series/38.104 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- 3GPP Technical Report 38.901 v16.1.0, Study on channel model for frequencies from 0.5 to 100 GHz (Release 16), 2020. Available online: https://www.3gpp.org/ftp/Specs/archive/38_series/38.901 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.