Deep Learning Assisted Composite Clock: Robust Timescale for GNSS Through Neural Network †

Abstract

1. Introduction

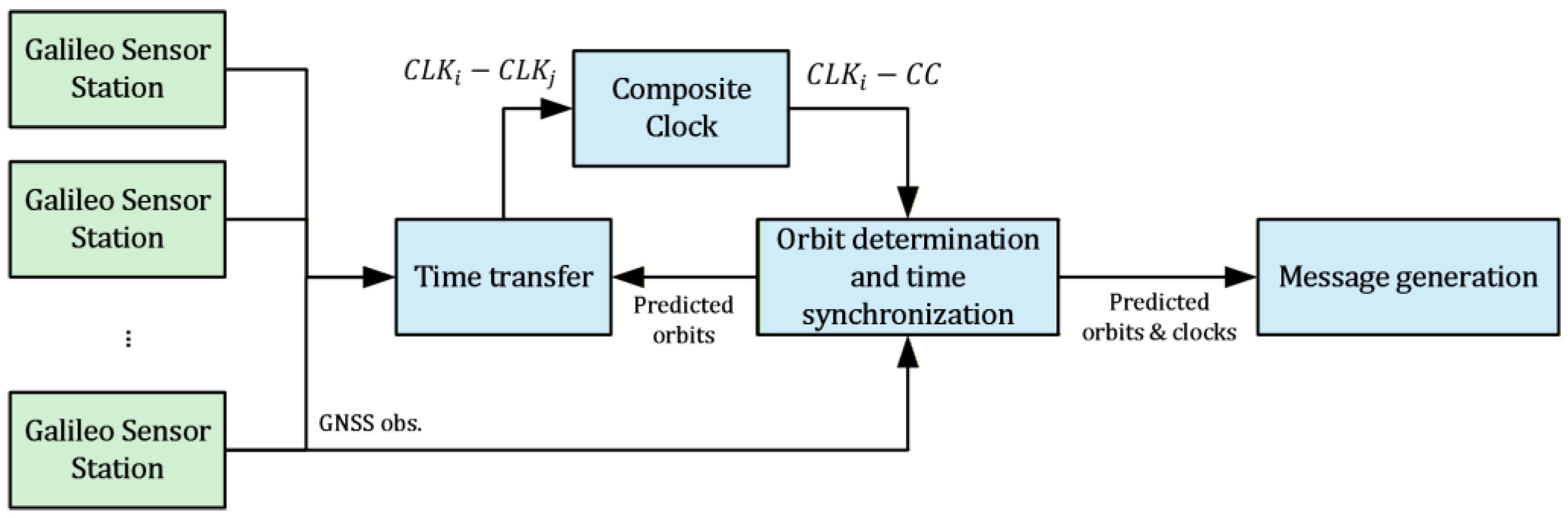

2. Basics of the Composite Clock for GNSS

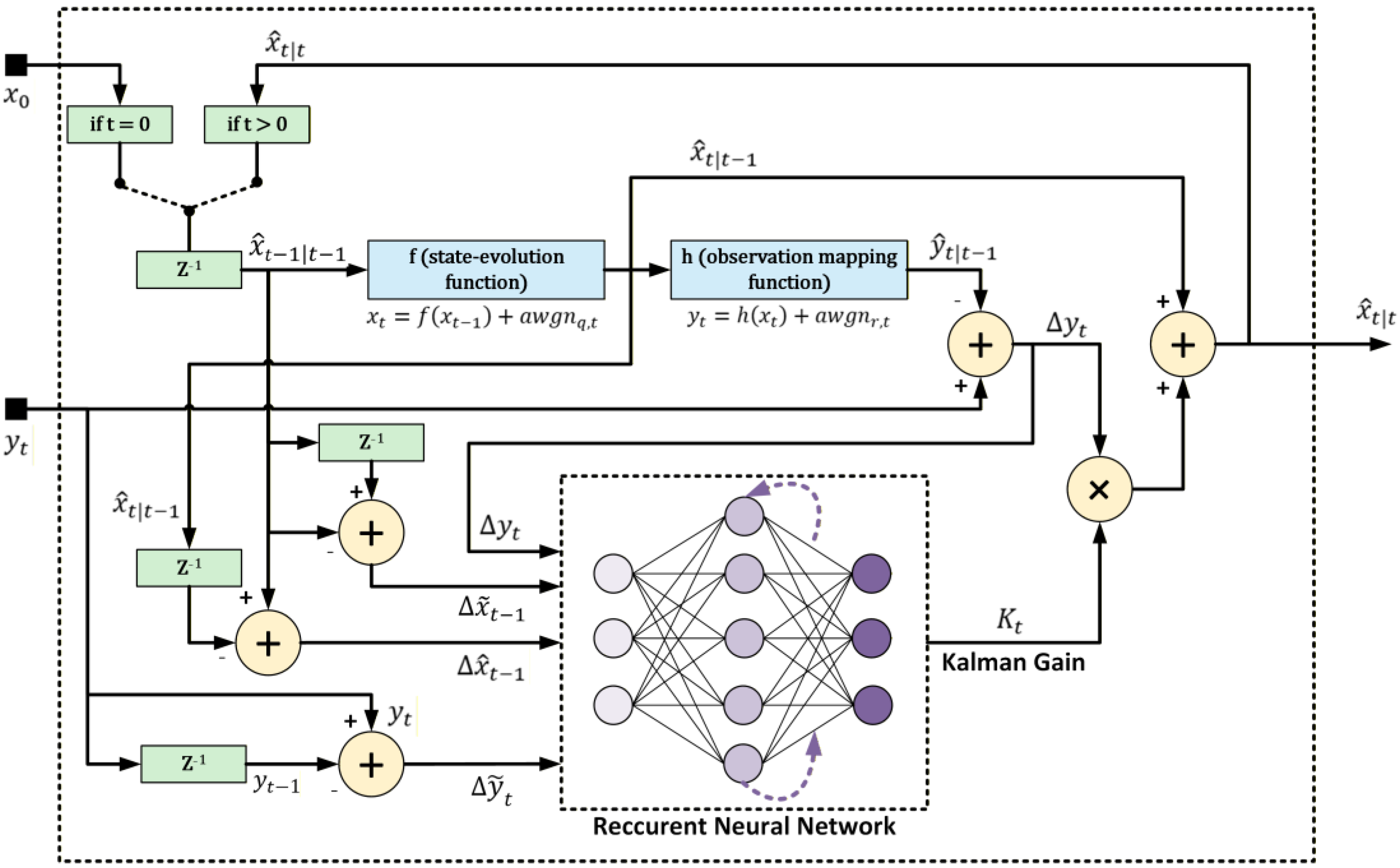

3. Machine Learning Assisted Kalman Filter

- Any anomalies in given clock behavior (frequency and/or phase drift, data gaps) can affect the next state prediction and thus computation.

4. Dataset Construction, Recurrent Neural Network Settings and Performance Evaluation

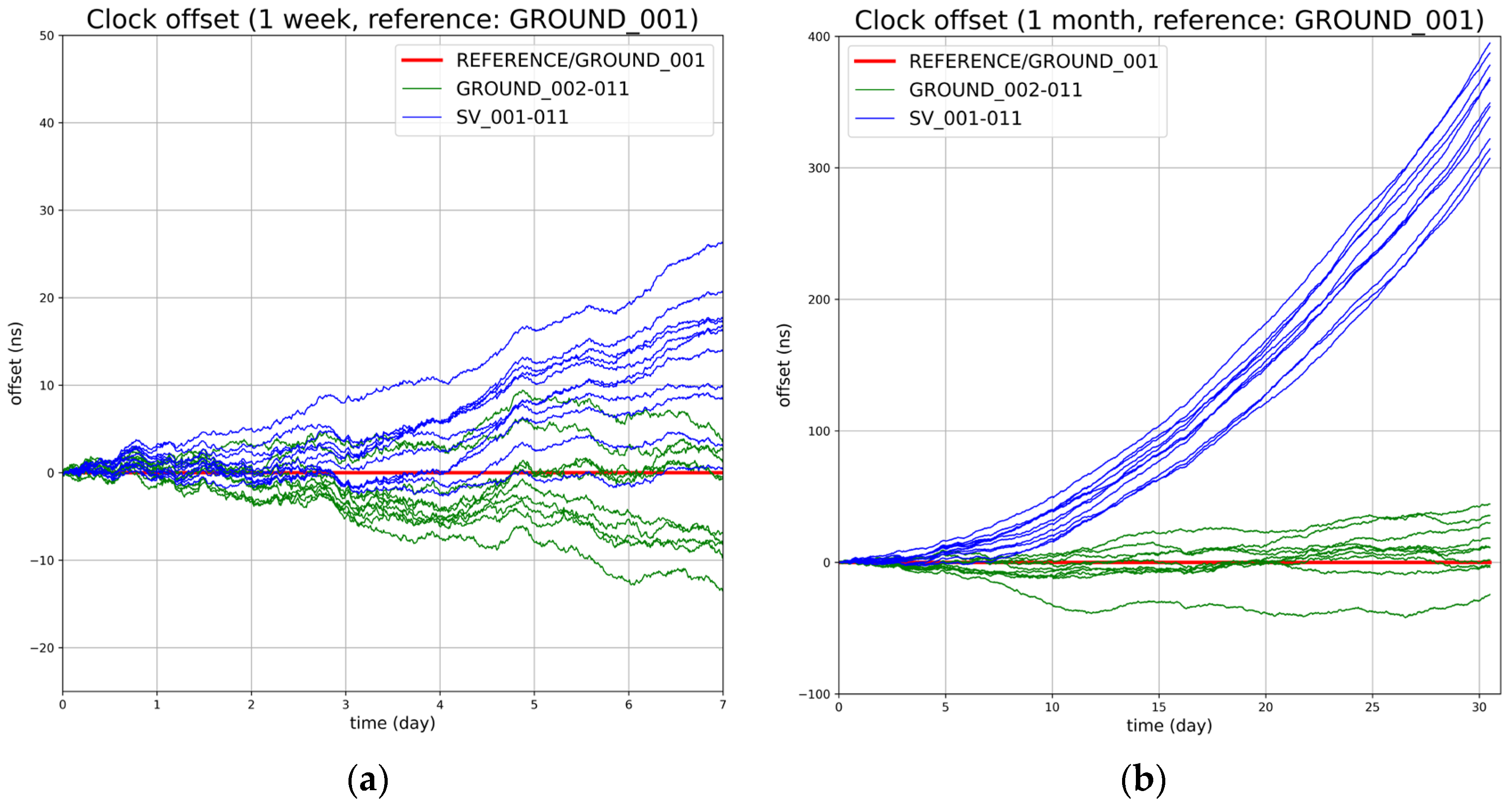

4.1. Dataset Construction

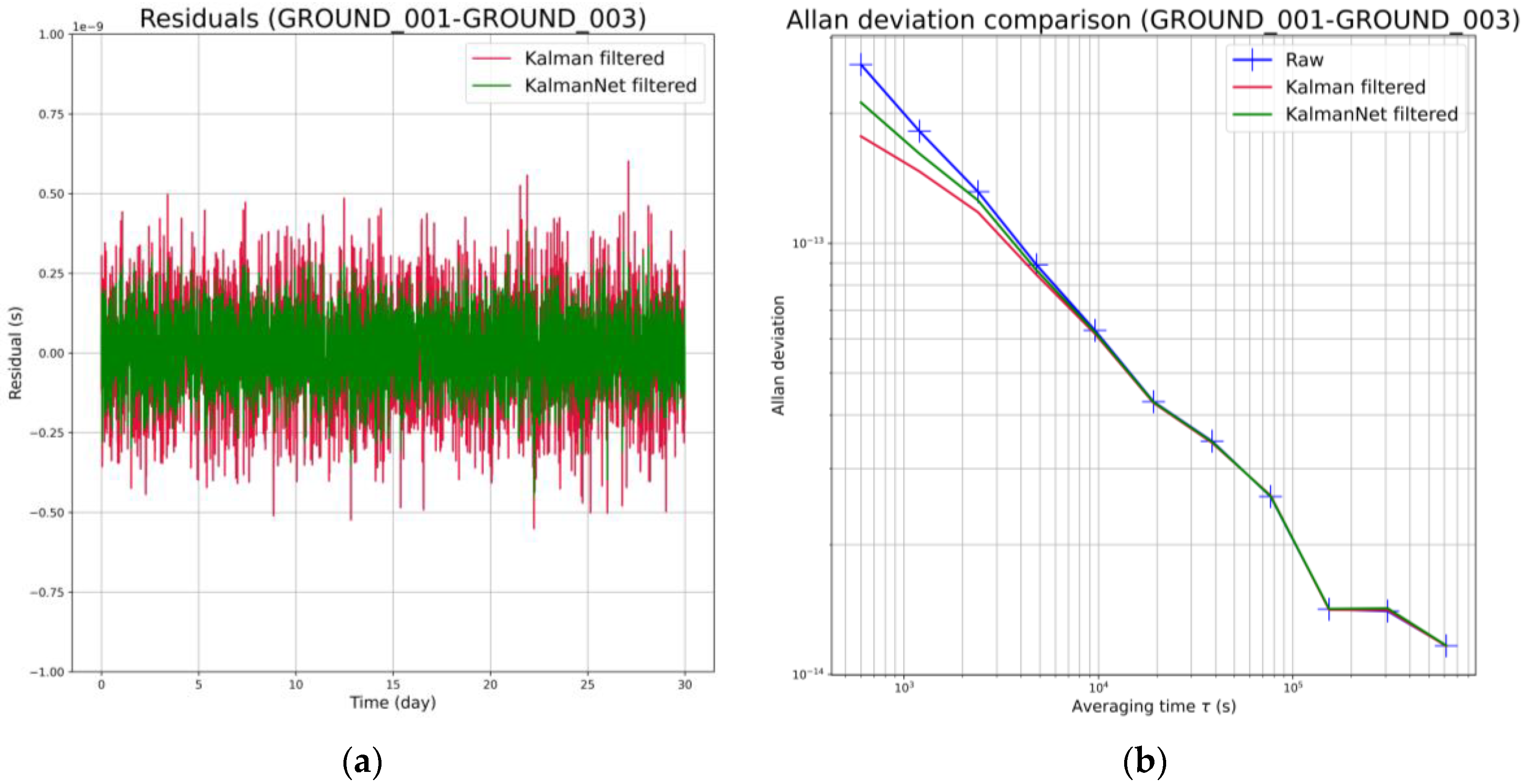

4.2. Recurrent Neural Network Settings and Performance Evaluation

- : The number of neurons embedded into the RNN. In the context of KalmanNet usage and for convenience, will represent the number of neurons embedded in each different layer of the RNN (all layers share the same number of neurons).

- : The number of times the entire dataset is passed through the RNN.

- : The number of samples injected to train the neural network.

- : Batch size, representing the number of samples that will be propagated through the network at the same time.

- 1-GRU: Architecture that considers one Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) between the linear input and linear output layers. This architecture can be considered fully connected, giving more independence to the RNN to formulate the Kalman gain .

- 3-GRU: Architecture that considers 3 GRU, with each one dedicated to the prediction of the process covariance , the state estimate covariance , and the residuals covariance . This architecture more significantly constrains the RNN, reducing the overall abstraction and number of trainable parameters, leading generally to better performance in terms of computation time. At , it has been chosen to initialize this parameter as in a traditional Kalman filter, which are then adjusted at each RNN round of computation.

5. Outlook and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BIPM | Bureau International des Poids et Mesures |

| CC | Composite Clock |

| DLACC | Deep Learning Assisted Composite Clock |

| DLR | Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (German Aerospace Center) |

| EAL | Échelle Atomique Libre (free atomic timescale) |

| FFM | Flicker Frequency Modulation |

| IGS | International GNSS Service |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NPL | National Physical Laboratory |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| RWFM | Random-Walk Frequency Modulation |

| SI | Système International (international system) |

| UTC | Universal Time Coordinated |

| WFM | White Frequency Modulation |

References

- Brown, K.R. The Theory of the GPS Composite Clock. In Proceedings of the 4th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation (ION GPS 1991), Albuquerque, NM, USA, 11–13 September 1991; pp. 223–243. [Google Scholar]

- Senior, K.; Koppang, P.; Ray, J. Developing an IGS Time Scale. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2003, 50, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorzi, M. Robust Kalman filtering under model perturbations. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2016, 62, 2902–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzi, M. On the robustness of the Bayes and Wiener estimators under model uncertainty. Automatica 2017, 83, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhini, A.; Perbellini, M.; Gottardi, S.; Yi, S.; Liu, H.; Zorzi, M. Learning the tuned liquid damper dynamics by means of a robust EKF. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.03520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revach, G.; Shlezinger, N.; Ni, X.; Escoriza, A.L.; Van Sloun, R.J.; Eldar, Y.C. KalmanNet: Neural Network Aided Kalman Filtering for Partially Known Dynamics. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2022, 70, 1532–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutsell, S. Relating the Hadamard Variance to MCS Kalman filter clock estimation. In Proceedings of the 27th PTTI Systems and Applications Meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, 29 November–1 December 1995; pp. 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Hutsell, S. Fine Tuning GPS Composite Clock Estimation in the MCS. In Proceedings of the 26th PTTI Systems and Applications Meeting, Reston, VA, USA, 6–8 December 1994; pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Satin, A.; Leondes, C. Ensembling Clocks of Global Positioning System. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 1990, 26, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S. Time Scales Demystified. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Frequency Control Symposium and PDA Exhibition Jointly with the 17th European Frequency and Time Forum, Tampa, FL, USA, 4–8 May 2003; pp. 223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Senior, K.L.; Coleman, M.J. The Next Generation GPS Time. NAVIGATION J. Inst. Navig. 2017, 64, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldan, P.; Trilles, S.; Serena, X.; Tajdine, A. Novel Composite Clock Algorithm for the Generation of Galileo Robust Timescale. In Proceedings of the 35th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+ 2022), Denver, CO, USA, 19–23 September 2022; pp. 2790–2799. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton Technical Services. STABLE32 User Manual; Hamilton Technical Services: Beaufort, SC, USA, 2008; Available online: http://www.stable32.com/Manual154.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

| Clock Type | Time Series Configuration |

|---|---|

| Ground | |

| (Random-Walk Frequency Modulation) | |

| (Flicker Frequency Modulation) | |

| (White Frequency Modulation) | |

| (frequency drift) | |

| Space | |

| (Random-Walk Frequency Modulation) | |

| (Flicker Frequency Modulation) | |

| (White Frequency Modulation) | |

| (frequency drift) |

| Clock Ensemble | Config. | Arch. | (s) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GROUND_001 - GROUND_003 | 1 | 1-GRU | 40 | 25 | 1000 | 100 | 323 | 1.72489 × 10−10 | 1.60188 × 10−10 |

| 2 | 1-GRU | 40 | 25 | 4000 | 1000 | 931 | 1.56059 × 10−10 | 1.60188 × 10−10 | |

| 3 | 1-GRU | 40 | 50 | 1000 | 100 | 524 | 1.39614 × 10−10 | 1.60188 × 10−10 | |

| 4 | 1-GRU | 40 | 50 | 4000 | 1000 | 1738 | 1.24873 × 10−10 | 1.60188 × 10−10 | |

| 5 | 3-GRU | 40 | 25 | 1000 | 100 | 253 | 1.39167 × 10−10 | 1.60188 × 10−10 | |

| 6 | 3-GRU | 40 | 25 | 4000 | 1000 | 853 | 1.31466 × 10−10 | 1.60188 × 10−10 | |

| 7 | 3-GRU | 40 | 50 | 1000 | 100 | 413 | 1.01084 × 10−10 | 1.60188 × 10−10 | |

| 8 | 3-GRU | 40 | 50 | 4000 | 1000 | 1473 | 1.00498 × 10−10 | 1.60188 × 10−10 | |

| GROUND_001 - SV_007 | 1 | 1-GRU | 40 | 25 | 1000 | 100 | 316 | 1.70944 × 10−10 | 1.20055 × 10−10 |

| 2 | 1-GRU | 40 | 25 | 4000 | 1000 | 953 | 1.44622 × 10−10 | 1.20055 × 10−10 | |

| 3 | 1-GRU | 40 | 50 | 1000 | 100 | 523 | 1.33926 × 10−10 | 1.20055 × 10−10 | |

| 4 | 1-GRU | 40 | 50 | 4000 | 1000 | 1697 | 1.18975 × 10−10 | 1.20055 × 10−10 | |

| 5 | 3-GRU | 40 | 25 | 1000 | 100 | 259 | 1.38892 × 10−10 | 1.20055 × 10−10 | |

| 6 | 3-GRU | 40 | 25 | 4000 | 1000 | 838 | 1.31793 × 10−10 | 1.20055 × 10−10 | |

| 7 | 3-GRU | 40 | 50 | 1000 | 100 | 427 | 1.02095 × 10−10 | 1.20055 × 10−10 | |

| 8 | 3-GRU | 40 | 50 | 4000 | 1000 | 1438 | 1.01168 × 10−10 | 1.20055 × 10−10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fayon, G.; Mudrak, A.; Sobreira, H.; Castillo, A. Deep Learning Assisted Composite Clock: Robust Timescale for GNSS Through Neural Network. Eng. Proc. 2026, 126, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2026126002

Fayon G, Mudrak A, Sobreira H, Castillo A. Deep Learning Assisted Composite Clock: Robust Timescale for GNSS Through Neural Network. Engineering Proceedings. 2026; 126(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2026126002

Chicago/Turabian StyleFayon, Gaëtan, Alexander Mudrak, Hugo Sobreira, and Artemio Castillo. 2026. "Deep Learning Assisted Composite Clock: Robust Timescale for GNSS Through Neural Network" Engineering Proceedings 126, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2026126002

APA StyleFayon, G., Mudrak, A., Sobreira, H., & Castillo, A. (2026). Deep Learning Assisted Composite Clock: Robust Timescale for GNSS Through Neural Network. Engineering Proceedings, 126(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2026126002