Abstract

Alumina ceramics, known for their hardness, thermal resistance, and chemical stability, are widely applied in engineering and industry. This study investigates the flexural strength of 95% and 99% alumina ceramics using tubes with two or four cross-sectional holes, tested by 3-point and 4-point bending methods. Macroscopic analysis was performed with a Leica DM6M microscope to determine specimen areas and ensure measurement accuracy. Results indicate that 99% alumina ceramics exhibit approximately 35% higher bending strength compared to 95% alumina ceramics, highlighting the influence of alumina content on mechanical performance.

1. Introduction

Ceramics represent one of humanity’s earliest technological achievements, influencing societal development through their historical use in construction, tools, and decorative objects. Over time, their applications have expanded into advanced fields such as engineering, electronics, and materials science. Beyond shaping clay, ceramics integrate scientific knowledge, technical expertise, and innovative design, offering a unique combination of structural performance and adaptability [1,2,3].

Alumina (Al2O3) ceramics are particularly valued for their mechanical strength, chemical stability, and thermal resistance. Depending on the processing method, hydrated, calcined, and tabular alumina provide distinct structural features suitable for applications ranging from glazes to refractories, making them essential in engineering, electronics, and biomedical fields [4,5].

Enhancing the properties of alumina ceramics has been extensively studied. Nano CuO and TiO2 additions (up to 4 wt%) improve densification, hardness, fracture toughness, and wear resistance by promoting liquid- and solid-state sintering and inhibiting abnormal grain growth [6]. Similarly, MgO, La2O3, and ZrO2 synergistically increase densification, transparency, and mechanical performance, with optimized formulations achieving near-full density, high infrared and visible transmittance, and superior hardness and flexural strength [7].

Additive manufacturing techniques, particularly stereolithography (SLA), further influence performance. Print orientation strongly affects fracture behavior, with perpendicular orientation yielding the highest strength. Quasi-static loading primarily produces intergranular fracture, while dynamic loading results in mixed intergranular and transgranular failure, offering insights for designing high-performance AM ceramic components [8].

Alumina ceramics are also crucial in machining applications. Ceramic cutting inserts, due to their hardness and thermal resistance, enable higher cutting speeds and wear resistance compared to cemented carbide. Performance can be enhanced via whiskers, nanoparticles, nanotubes, structural modifications, and advanced sintering, while offering sustainability benefits through reduced coolant usage and decreased reliance on critical raw materials [9].

Finally, sintering aids such as CaO, TiO2, La2O3, and ZrO2 play a key role in SLA-fabricated alumina. CaO increases internal porosity and interlayer microcracking, TiO2 improves bending strength via Al2TiO5 formation, La2O3 provides modest high-temperature strength gains, and ZrO2 enhances shear strength without reducing bending strength. Optimized powder compositions and sintering conditions yield alumina ceramics with balanced density, mechanical performance, and thermal stability suitable for ceramic core applications [10].

In this work, 95% and 99% alumina ceramics are investigated for their flexural strength. The following section presents the specimen design and testing methods, including 3-point and 4-point bending, followed by the experimental results. The study concludes with a discussion of the key findings, highlighting that 99% alumina exhibits approximately 35% higher bending strength than 95%, emphasizing the influence of alumina content on mechanical performance.

2. Materials and Methods

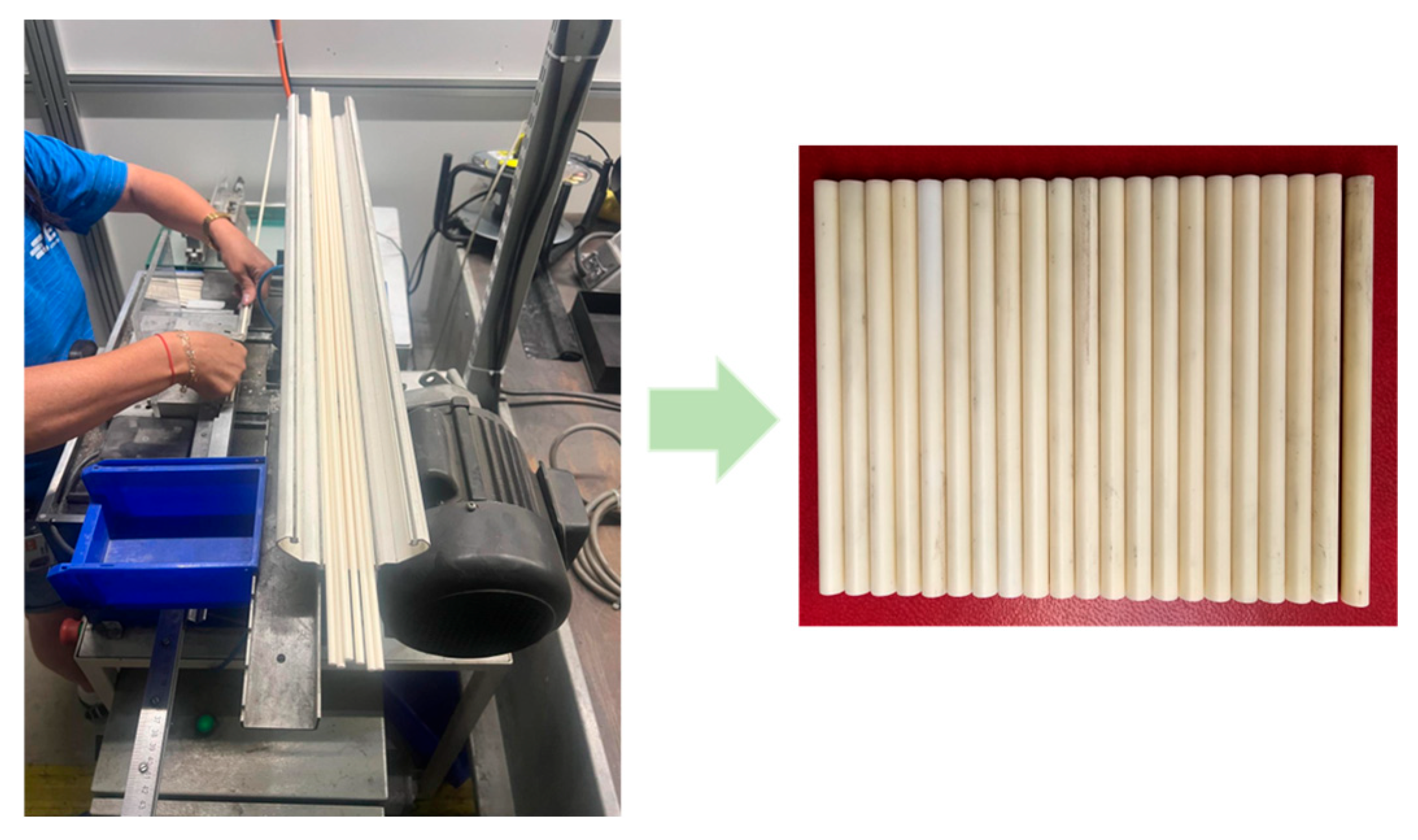

The materials investigated in this study were 95% and 99% Alumina Ceramics (Electro Precision, Vallet, France). These materials are suitable for applications within a temperature range of 0 °C to 1800 °C. The test specimens were extracted from a 1000 mm long bar, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The process of sampling.

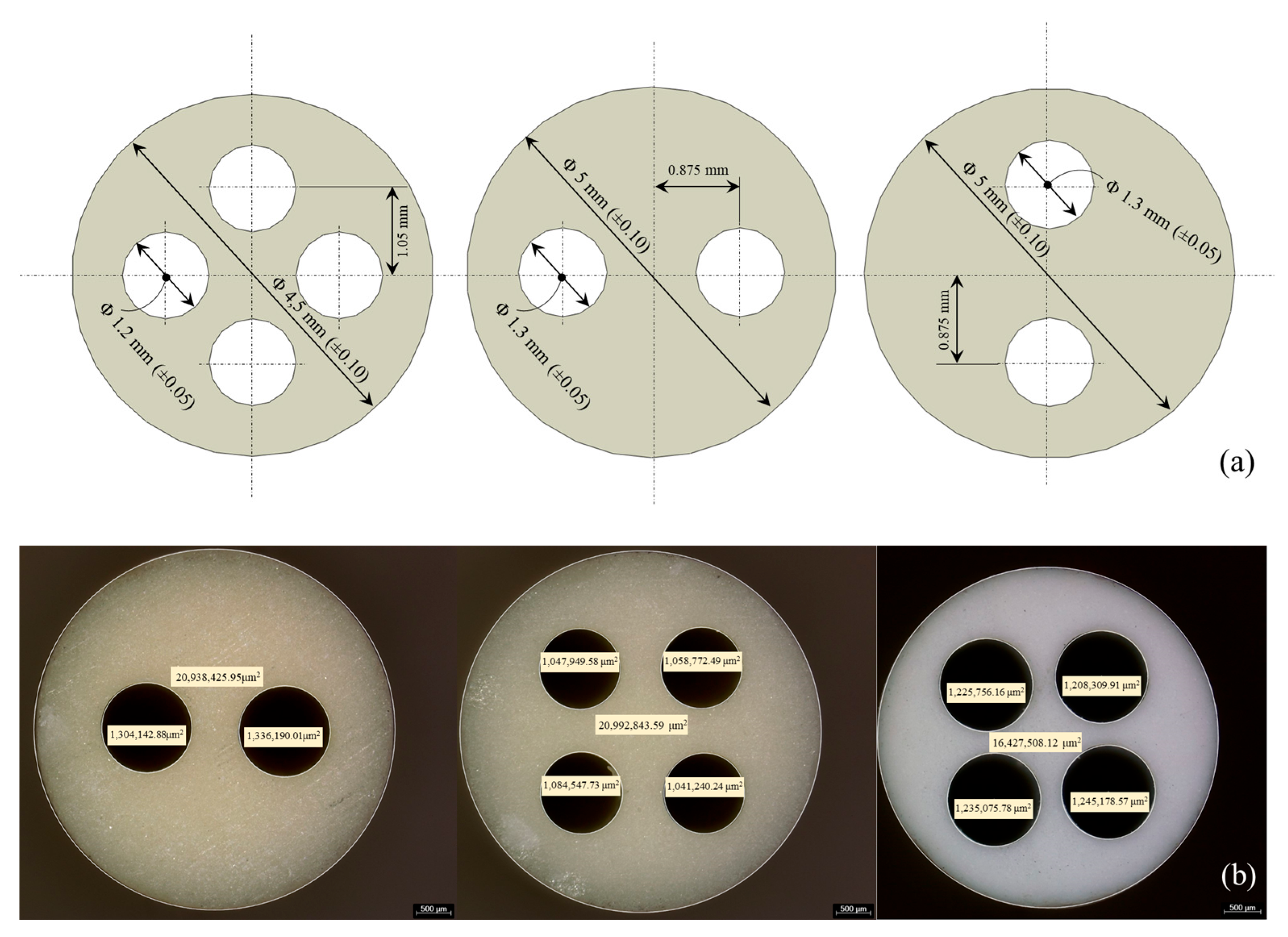

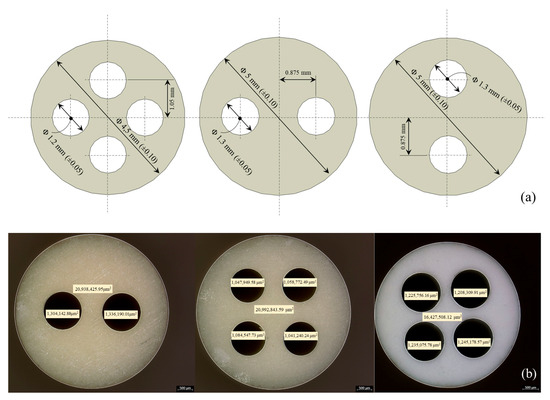

The bars were manufactured in two configurations, containing either two holes or four holes along their length. The outer diameter was measured using a caliper to determine the cross-sectional area, and for improved measurement accuracy, a Leica DM6M microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) was employed (Figure 2). The specimens were subsequently cut to the required test dimensions of 180 mm and 80 mm using an abrasive strip.

Figure 2.

Specimens section (a) measured with a caliper, and (b) measured with a Leica DM6M microscope.

Both three-point bending (3PB) and four-point bending (4PB) tests were conducted to evaluate the mechanical behavior of the specimens. Specimens with a length of 180 mm were tested under the 4PB configuration, while shorter specimens of 80 mm were subjected to the 3PB configuration.

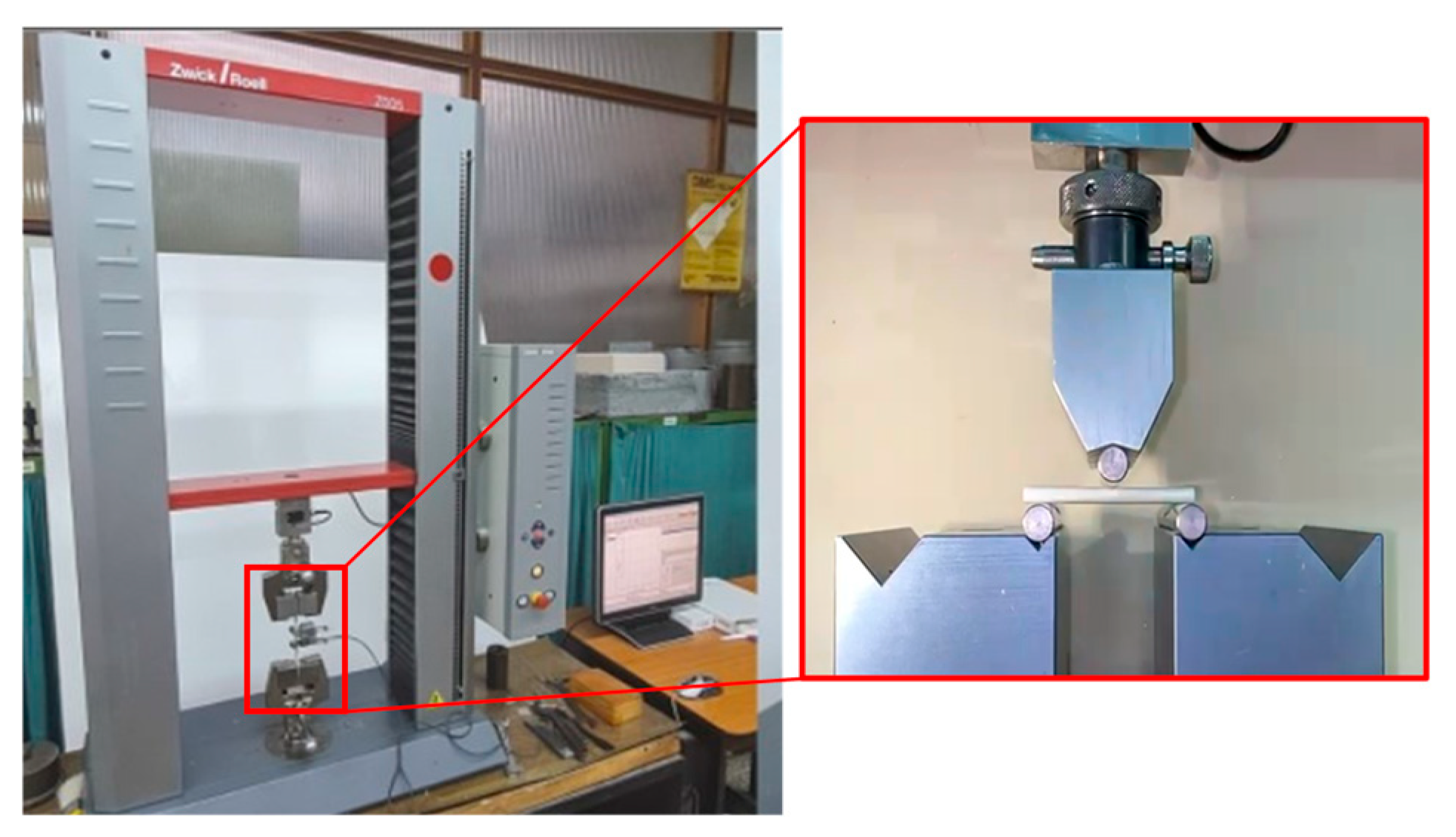

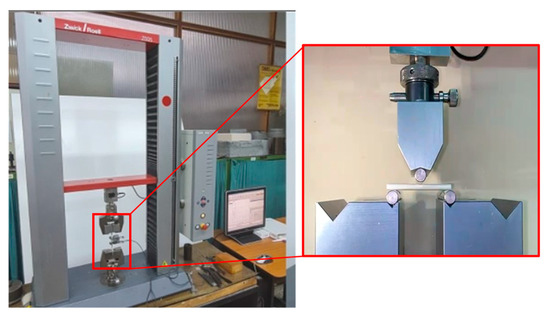

All tests were carried out using a Zwick universal testing machine (Zwick Roell Group, Ulm, Germany) equipped with a 5 kN load cell. The crosshead speed was maintained at 2 mm/min throughout the experiments (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Zwick machine and the 3PB tool.

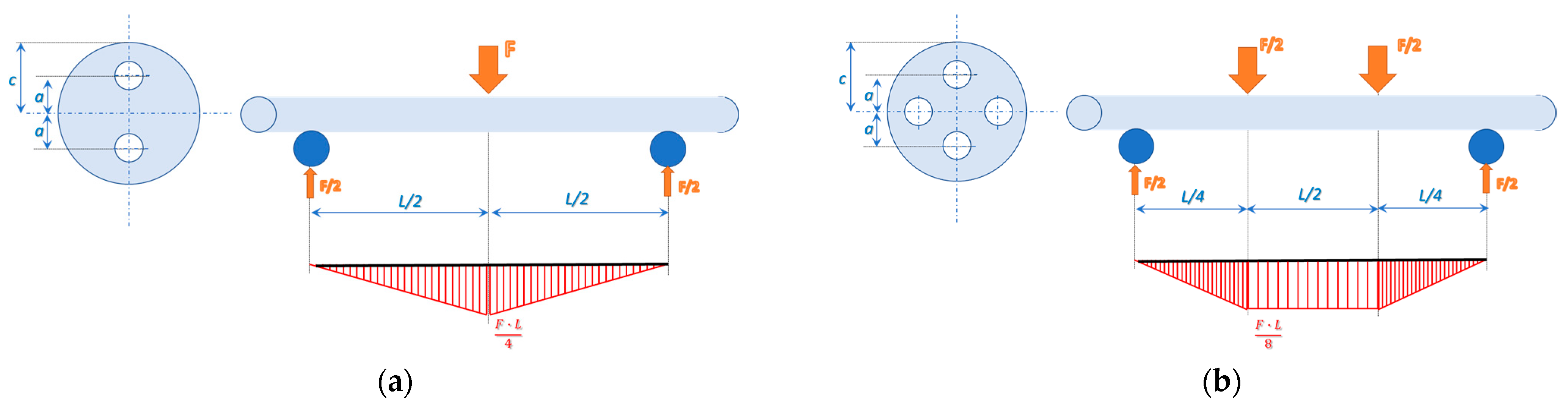

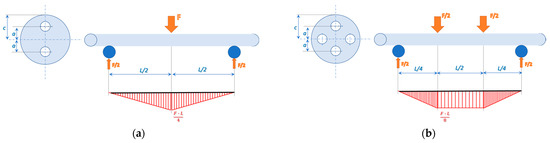

For the 3PB test, the support span length was set to 50 mm, with the force applied symmetrically at the midpoint between the supports. For the 4PB test, the support span length was 80 mm, and the total load was divided into two equal forces applied symmetrically, with a distance of 40 mm between the points of load application, Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Test setups for (a) three-point bending (3PB) and (b) four-point bending (4PB), along with the corresponding bending moment diagrams.

The flexural strength was determined using Equation (1). In this formulation, Mi denotes the maximum bending moment, as identified from the bending moment distributions illustrated in Figure 4. The parameter c represents the maximum distance from the neutral axis to the outermost fiber in the bending plane, which for circular specimens corresponds to the radius. The term I is the second moment of area (moment of inertia). For a plain circular cross-section with two vertically aligned holes, I was calculated according to Equation (3). When the cross-section consisted of a circular profile with two horizontally aligned holes, Equation (4) was used, while for the circular cross-section containing four holes, Equation (5) was applied.

These definitions ensure consistency between the geometrical characteristics of the specimens and the applied loading configurations, thereby enabling a rigorous evaluation of the flexural response.

3. Results

This section presents the experimental results and discussion on the flexural behavior of alumina ceramics with two different purities (95% and 99%). The specimens were subjected to both three-point bending (3PB) and four-point bending (4PB) tests in order to evaluate their mechanical response under distinct loading configurations. The test specimens were cylindrical in shape and incorporated either two or four holes. For the case of two-hole specimens, the orientation during testing was considered in both vertical and horizontal positions. The following subsections analyze the influence of material purity, loading configuration, and hole geometry on the resulting flexural strength.

3.1. Three-Point Bending

3.1.1. Three-Point Bending Behavior of Circular Sections with Four Holes

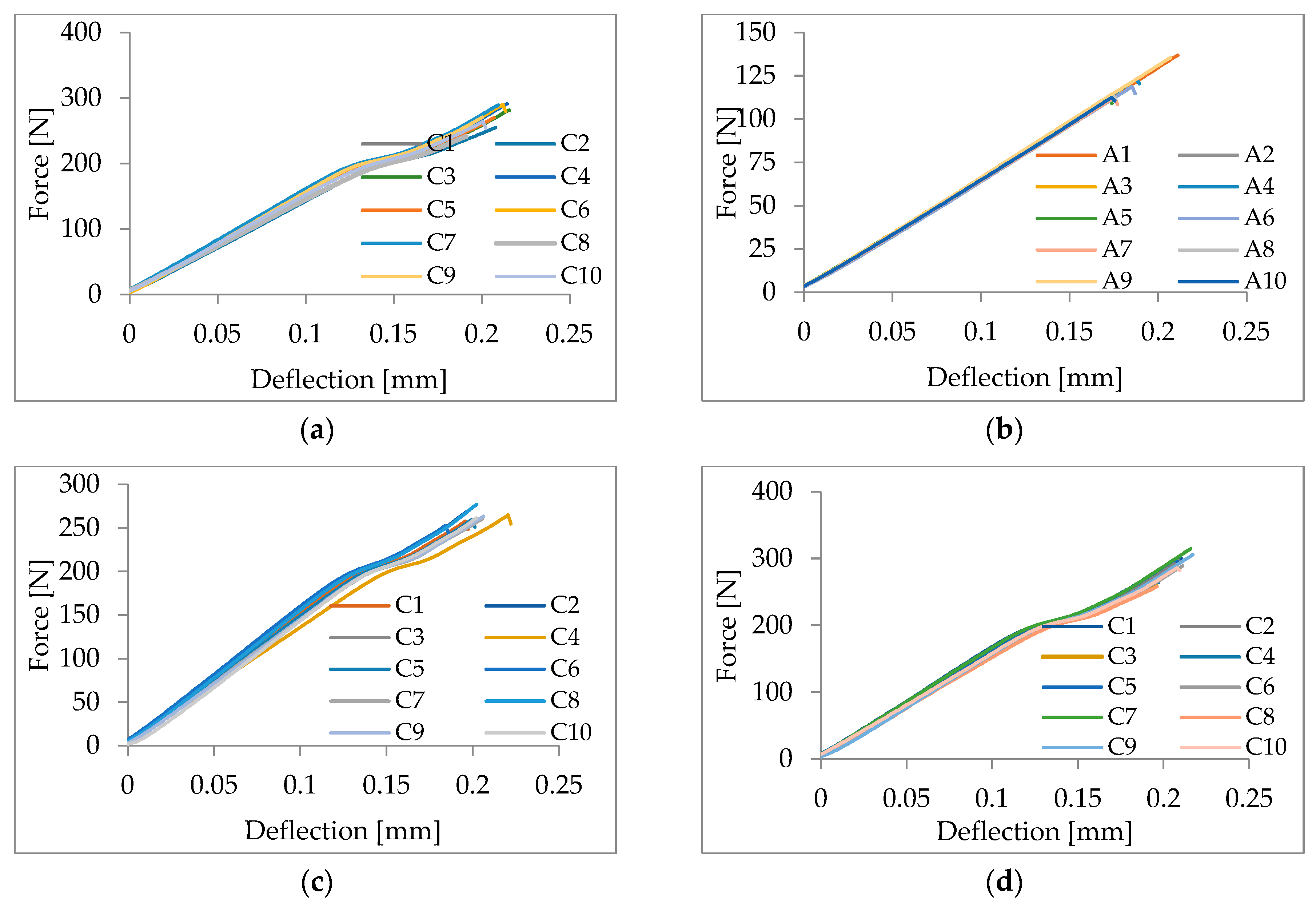

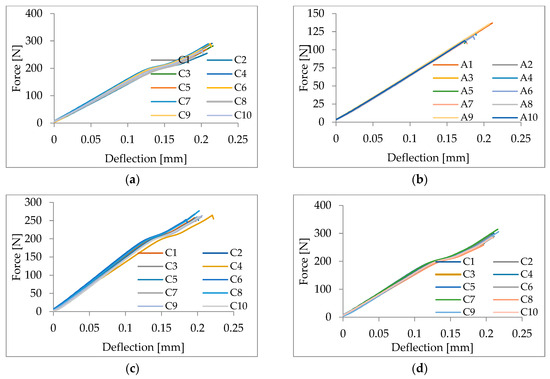

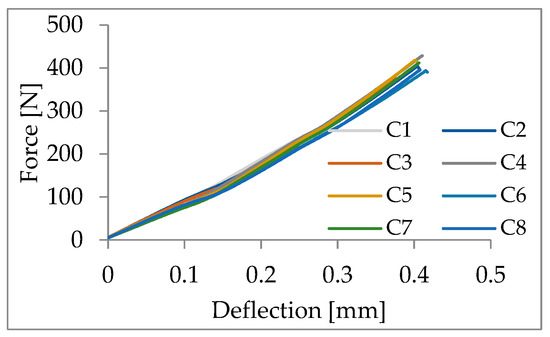

For the three-point bending tests, specimens of both 99% pure alumina ceramic and 95% pure alumina ceramic were tested. Ten specimens were tested for each material. Figure 5 shows the force–displacement curves obtained for the two cases.

Figure 5.

Force–deflection curves obtained for (a) 99% pure alumina ceramic, (b) 95% pure alumina ceramic, (c) 99% pure alumina ceramic with vertically aligned holes, and (d) 99% pure alumina ceramic with horizontally aligned holes.

It can be clearly seen that, for 99% pure alumina ceramic, the measured forces ranged between 241 and 291 N, which corresponds to bending strength values from 268 to 327 MPa. In comparison, the 95% pure alumina ceramic exhibited lower maximum forces, ranging from 111 to 137 N, with bending strength values between 164 and 201 MPa. These results highlight the significant influence of material purity on the bending performance of alumina ceramics.

Similarly, the displacements measured for 99% and 95% pure alumina ceramics were very close, falling within the narrow range of 0.19 to 0.22 mm, indicating comparable deformation behavior for both materials.

3.1.2. Three-Point Bending Behavior of Circular Sections with Vertically Aligned Holes

For the three-point bending tests of circular sections with vertically aligned holes, only 99% pure alumina ceramic specimens were tested. Ten specimens were used for this material. Figure 5c shows the force–displacement curves obtained for these tests.

3.1.3. Three-Point Bending Behavior of Circular Sections with Horizontally Aligned Holes

Moreover, circular sections with horizontally aligned holes were tested under three-point bending, using only 99% pure alumina ceramic specimens. Ten specimens were examined, and the force–displacement curves obtained are presented in Figure 5d.

3.2. Four-Point Bending

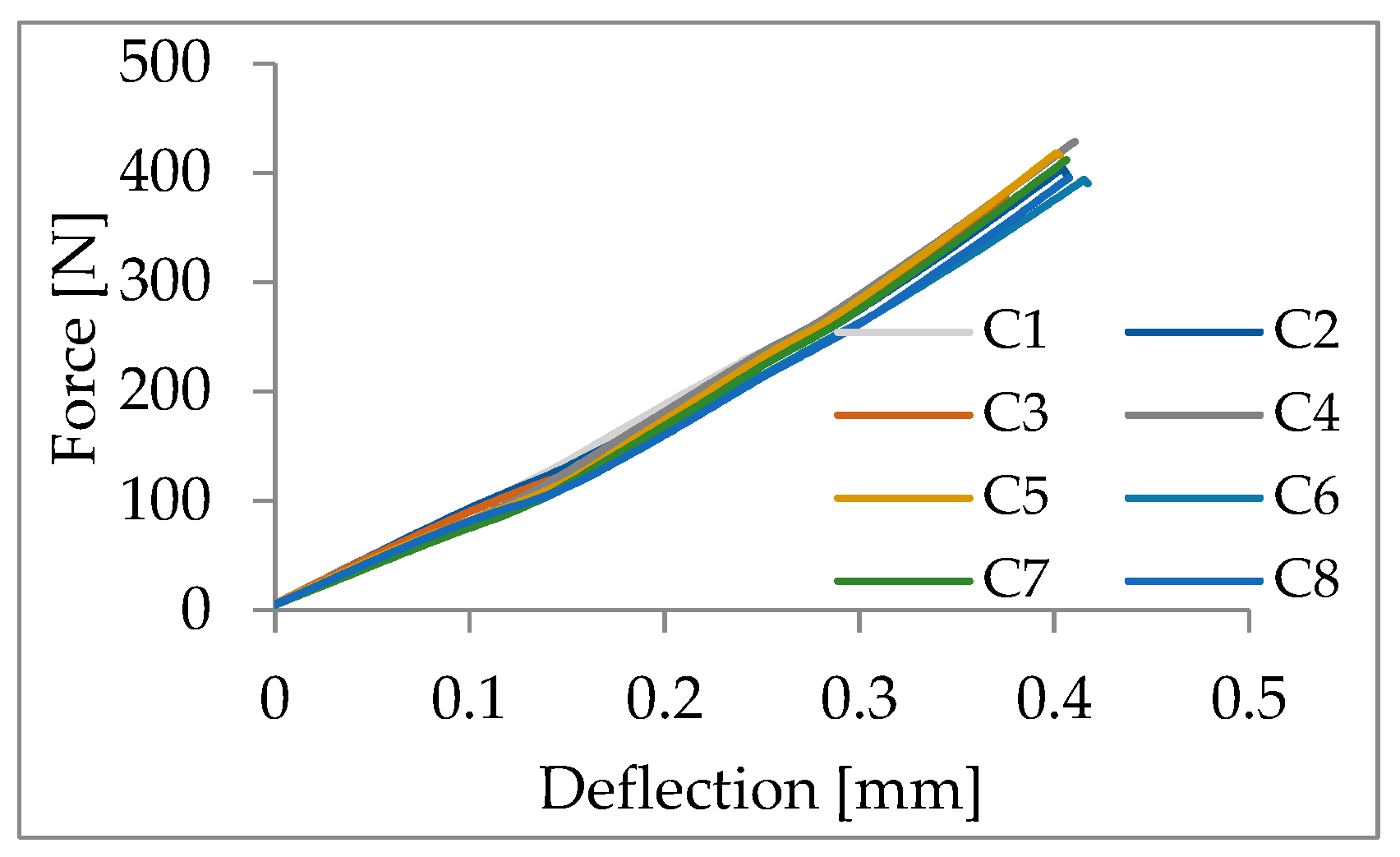

Four-point bending tests were carried out on circular sections containing four holes, using specimens of 99% pure alumina ceramic. Eight specimens were tested in total. Figure 6 presents the corresponding force–displacement curves.

Figure 6.

Force–deflection curves obtained from four-point bending tests of 99% pure alumina ceramic specimens with four holes.

4. Discussion

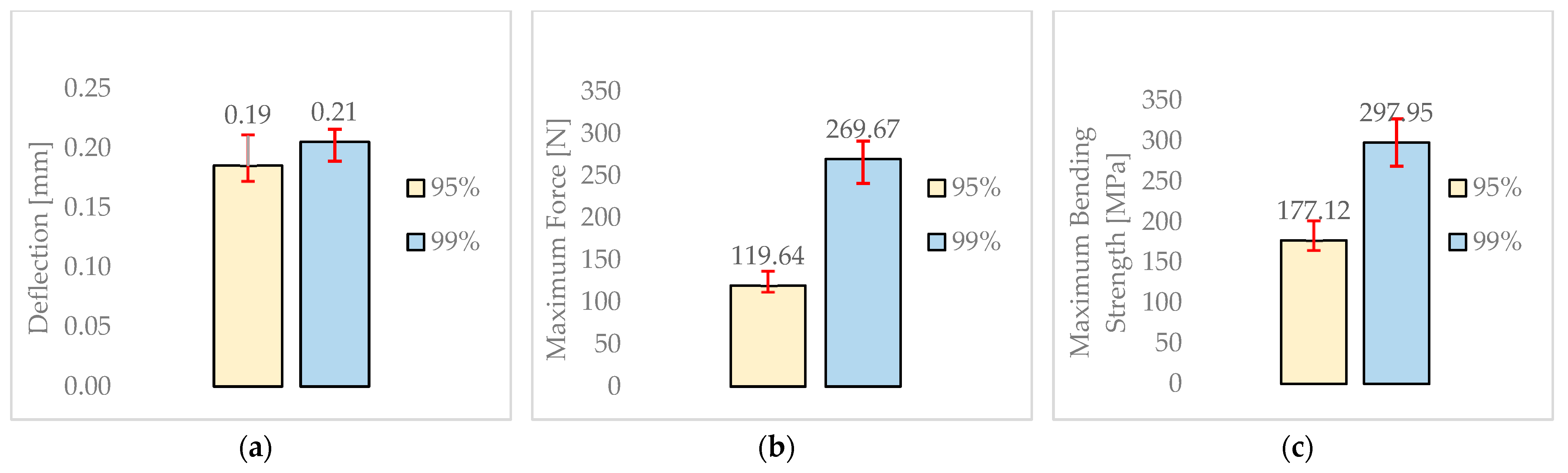

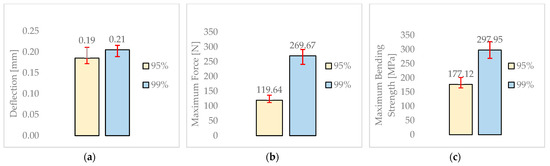

In the present study, the bending behavior of 99% and 95% pure alumina ceramic specimens was investigated. Figure 7 summarizes the main results: subfigure (a) shows the deflection, (b) presents the maximum force recorded, and (c) displays the corresponding bending strength for both materials. The data indicate that the higher-purity ceramic exhibits slightly greater bending resistance under the same loading conditions, highlighting the influence of material purity on mechanical performance.

Figure 7.

Comparison of (a) deflection, (b) maximum force, and (c) maximum bending strength for 99% and 95% pure alumina ceramic specimens.

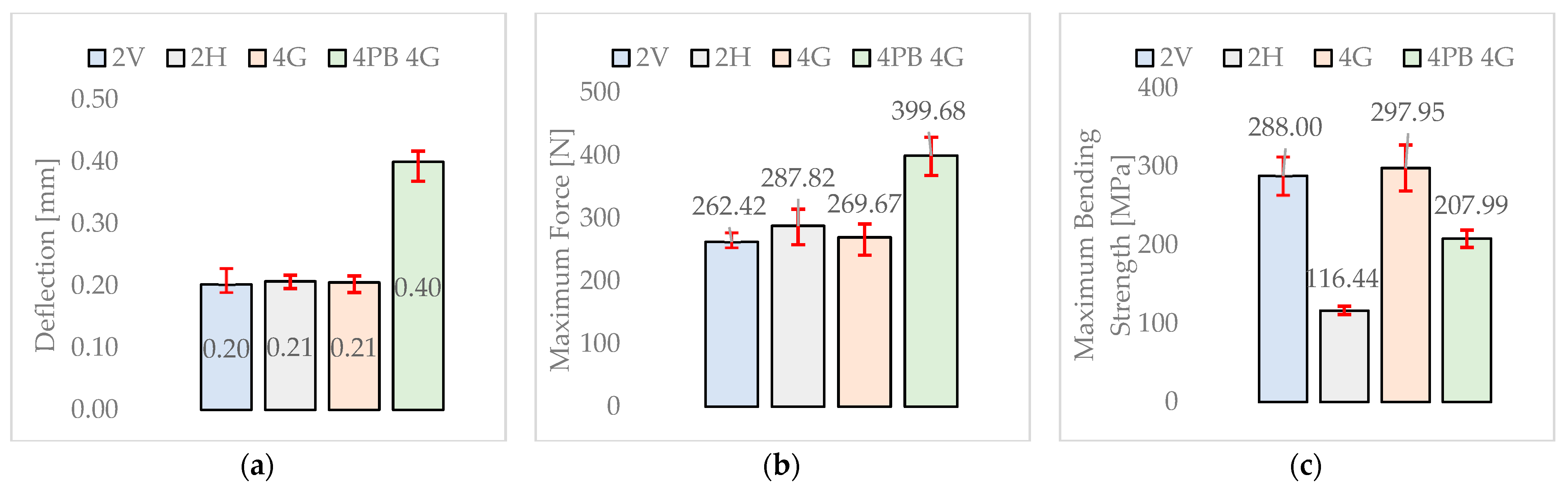

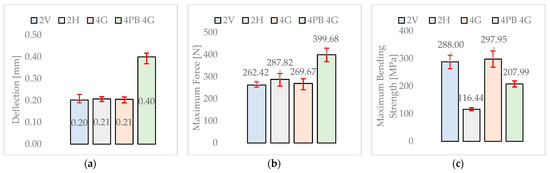

Figure 8 provides a comparison of the bending behavior of 99% pure alumina ceramic, considering both the number and the arrangement of holes. Panels (a), (b), and (c) present the deflection, maximum force, and maximum bending strength, respectively, for the four configurations studied.

Figure 8.

Effect of hole number and arrangement on the bending response of 99% pure alumina ceramic: (a) deflection, (b) maximum force, and (c) maximum bending strength.

Deflection was nearly identical for the specimens subjected to 3PB with 2 holes arranged vertically (2V), 2 holes arranged horizontally (2H), and four holes (4G) (~0.20–0.21 mm), while 4PB specimens with four holes (4PB 4G) showed a significantly higher value (0.40 mm), indicating reduced stiffness. The maximum force was greatest for 4PB with four holes (399.68 N), far exceeding the other configurations (262–288 N), indicating improved load distribution. In contrast, the maximum bending strength was highest for 4G (297.95 MPa) and 2V (288.00 MPa), intermediate for 4PB 4G (207.99 MPa), and lowest for 2H (116.44 MPa). These results highlight that 4G and 2V optimize bending strength, 4PB 4G enhances load capacity at the expense of strength, and 2H is the least favorable arrangement.

5. Conclusions

The experimental results demonstrate that high-purity alumina (99%) exhibits superior flexural strength compared to lower-purity alumina (95%). This enhancement is primarily attributed to the reduced presence of secondary phases and the formation of a more homogeneous and denser microstructure. For specimens containing four holes, the flexural strength of the 99% alumina ceramics was 40% higher than that of their 95% alumina counterparts. Within the 99% alumina group, the flexural strength of specimens with four holes exceeded that of specimens with two vertically aligned holes by only 3.3%, indicating a limited effect of increasing the number of holes in this configuration.

Moreover, specimens with horizontally aligned holes demonstrated a pronounced improvement in mechanical performance, exhibiting flexural strengths 59.5% higher than those with two vertically aligned holes and 60.9% higher than those with four holes. These findings highlight the critical role of hole arrangement and number in governing the flexural response of ceramic components. The relatively small difference between specimens with four holes and those with two vertically aligned holes further suggests that hole geometry can be strategically optimized to enhance the mechanical performance of alumina ceramics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-V.G. and V.T.P.; methodology, S.-V.G. and C.-F.P.; software, S.-V.G. and C.-F.P.; validation, S.-V.G., V.T.P., and C.-F.P.; formal analysis, C.-F.P.; investigation, S.-V.G. and V.T.P.; resources, L.M.; data curation, L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-V.G. and C.-F.P.; writing—review and editing, L.M.; visualization, S.-V.G.; supervision, L.M.; project administration, L.M.; funding acquisition, L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization, CNCS-UEFISCDI grant number PN-IV-P1-PCE-2023-1446.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are held by the authors and can be made available upon reasonable request. Requests for access to the data should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barsoum, M.W. Fundamentals of Ceramics, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, Y.-M.; Birnie, D.P.; Kingery, W.D. Physical Ceramics: Principles for Ceramic Science and Engineering; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Richerson, D.W.; Lee, W.E. Modern Ceramic Engineering: Properties, Processing, and Use in Design, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Piconi, C.; Maccauro, G.; Muratori, F.; Brach del Prever, E. Alumina and zirconia ceramics in joint replacements. J. Appl. Biomater. Biomech. 2003, 1, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shakir, R.A.; Géber, R. Zirconia-alumina ceramics: A study of their properties. Pollack Period. 2025, 20, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, P.; Modak, N.; Bhattacharya, T.K.; Sikder, R. Effect of nano oxides addition on tribo-mechanical behaviour of alumina ceramic in relation with sintering mechanism. Phys. Scr. 2025, 100, 0759b3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shargh, A.H.K.; Ramazani, M.; Jamali, H.; Davar, F.; Sharifi, E.M.; Torkian, S.; Nasresfahani, A.R. Enhanced mechanical and optical properties of alumina ceramics via simultaneous magnesium, lanthanum, and zirconium oxide addition in spark plasma sintering. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaiemyekeh, Z.; Rezasefat, M.; Kumar, Y.; Sayahlatifi, S.; Zheng, J.; Li, H.; Romanyk, D.L.; Hogan, J.D. On the role of stress state in the failure behavior of alumina ceramics via stereolithography: Quasi-static and dynamic loading. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 151, 607–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žmak, I.; Jozić, S.; Ćurković, L.; Filetin, T. Alumina-Based Cutting Tools—A Review of Recent Progress. Materials 2025, 18, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Hu, K.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, P.; Lu, Z. Effect of sintering aids on mechanical properties and microstructure of alumina ceramic via stereolithography. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 17506–17523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.