Abstract

High-fidelity numerical models are widely used to study the behavior of complex structures in Structural Health Monitoring (SHM), but their high computational cost limits their use in stochastic settings such as fleet-level applications. In practice, fleets of engineering assets show natural variability due to differences in loading, materials, and manufacturing, making them inherently stochastic. To address these challenges, this work develops a probabilistic surrogate model based on conditional variational autoencoders (CVAEs). The CVAE is trained to reconstruct the high-dimensional boundary response field of a critical structural region while explicitly conditioning on operational and structural parameters. By learning a latent probabilistic representation, the model explains the behavior of all individual members of a homogeneous population. Synthetic training and testing data are generated using a finite element model together with an aerodynamic panel model of a UAV. Results show that the CVAE can efficiently reproduce the spatial and stochastic features of the system response, providing accurate approximations at a fraction of the computational cost of high-fidelity simulations.

1. Introduction

Simulation models are inherent in Structural Health Monitoring (SHM), as they provide the descriptive and predictive insights needed to support decision-making. In general, SHM uses response data from in-service structures to assess their health state and inform downstream decisions [1]. If one considers the many sources of variability and/or noise involved in real-field applications, it follows that the confidence an operator can place in the decisions enabled by a deployed SHM system depends strongly on how uncertainty is managed. This is formally related to the concept of Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) [2], which implies the need for probabilistic methods.

A common feature of probabilistic methods for SHM is that they require a large number of forward evaluations of the simulation model to capture the expected variability in system response. The computational burden can increase even further when the parameter space is broadened, as in the case of populations of structures that are nominally, but not truly, identical. An attractive solution that has emerged recently as an alternative to expensive high-fidelity simulations is the use of surrogate modeling. Surrogate models can provide either point predictions of a quantity of interest (QoI) given some input variables or, in a probabilistic formulation, the full conditional probability density function (PDF). A straightforward example of the latter is the Gaussian Process (GP) model, which has been applied at both the single-structure level [3] and, as in [4], at the population level. In the latter case, the predictive mean of the GP captures the typical behavior of each member, while its predictive uncertainty quantifies the variability across the population.

A key challenge, however, is that most of the current SHM methodologies involve high-dimensional QoIs, i.e., spatially or temporally rich structural responses. In these cases, GPs as conventional probabilistic models become impractical; in their standard form they can only handle single outputs, while multi-output extensions exist [5] but their scalability deteriorates rapidly with increasing output dimensionality. Related Bayesian approaches, e.g., Bayesian neural networks [6], offer more flexibility but still suffer from costly inference and often poorly calibrated uncertainties.

Along these lines, recent research has turned toward generative models, which aim to learn the underlying PDF of the data. In engineering, the most recent advances have involved approaches such as variational autoencoders (VAEs) [7], diffusion models [8], and normalizing flows [9], among others. Of these, VAE-based models are the most mature and have found broader use as probabilistic surrogates in SHM. For example, a VAE was used to approximate the likelihood function in a framework for Bayesian structural model updating [10]. In most SHM tasks, however, the interest lies in predicting QoIs from monitored features, which naturally motivates conditional formulations. For this reason, conditional VAEs (CVAEs) have been employed in diverse contexts; e.g., for fatigue estimation of wind turbine blades based on SCADA data [11], for reduced-order modeling conditioned on time-series derived features [12], and for spatial field reconstruction conditioned on structural geometry parameters [13].

In this work, we employ CVAEs to reconstruct the boundary response field of a critical structural component under different sources of uncertainty, which represent the expected variations across a homogeneous population. The methodology is tailored to support submodeling, where the generative model provides localized responses required for downstream analyses at reduced computational cost. The CVAE is conditioned on flight telemetry data together with structural attributes of the submodeled region. To the authors’ best knowledge, this represents the first application of such architectures in a context like this. The proposed method is demonstrated on a UAV structure. A high-fidelity Finite Element (FE) model coupled with a panel aerodynamic model were employed to generate synthetic data at the region of interest for training and testing the deep learning model. Although still in an earlier stage, the results reveal that the employed model can effectively capture the variability induced by the population. Ultimately, the authors view the proposed approach as valuable in contexts where efficient UQ is desirable alongside global modeling approaches that involve high-dimensional data structures.

2. Methodology

Consider data obtained either directly from a structure in operation or generated by a corresponding simulation model. The dataset can be denoted for N data points, where are the D-dimensional input features (i.e., monitored quantities), and is the Q-dimensional QoI. The aim is to learn a predictor related to a regression or classification task. The QoI in this work is the displacement response in a specific region of the UAV structure, and the problem is therefore cast as a regression task. This satisfies the following:

where the additive random vector is a noise component and quantifies aleatoric uncertainty. In a computational setting, this term is typically negligible, since simulation outputs are deterministic.

In the context of SHM, the mapping f may represent a mechanical model (analytical or FE), which, in principle, is a stochastic model parametrized by a random vector . The parameters describe aspects related to the structure and its environment (e.g., structural attributes or loading), and from a population-based perspective, their variability can also be interpreted within the spectrum of aleatoric uncertainty. Equivalently, the regression problem can be written in probabilistic form as , where denotes the conditional distribution of the QoI. Predictive uncertainty is then obtained by marginalizing over :

where is the Dirac delta. In practice, this integral is evaluated approximately using Monte Carlo methods. However, such approaches are computationally prohibitive when is high-fidelity and is high-dimensional. To alleviate this burden, we introduce a probabilistic surrogate operator that directly approximates while being orders of magnitude cheaper to evaluate. Unlike deterministic surrogates, is generative, allowing efficient sampling of high-dimensional conditional QoIs. In this work, is realized using a CVAE.

CVAEs approximate the intractable conditional distribution using latent variables :

In this formulation, the encoder approximates the true posterior distribution over the latent variables, while the decoder generates high-dimensional outputs conditioned on inputs and latent codes. Training proceeds by maximizing the conditional Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO):

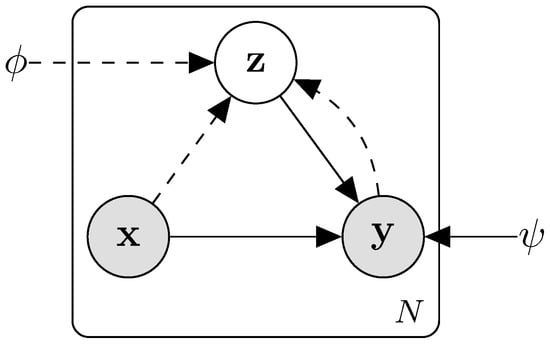

The first term, often referred to as the data-fit or reconstruction term, ensures that the decoder produces outputs consistent with the observed data. The second term acts as a regularizer, enforcing closeness of the approximate posterior to the prior distribution over . Its contribution is weighted by a coefficient . Typically, both the prior and the likelihood are taken as Gaussian; in this case, the reconstruction term corresponds to a mean-squared error (MSE) loss. In practice, both encoder and decoder are parameterized using deep neural networks, with their learnable parameters denoted by and , respectively. In this work, convolutional layers are employed to exploit spatial correlations in the displacement response fields. Figure 1 presents a directed acyclic graph (DAG) of the CVAE, showing the conditional dependencies between random variables.

Figure 1.

DAG of the CVAE latent variable model.

3. Case Study Description

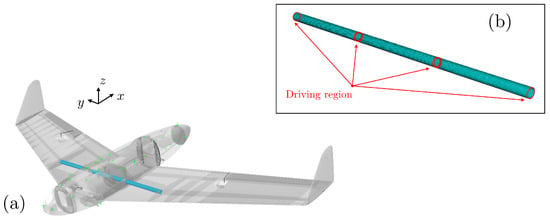

3.1. Critical Component

The critical component considered in this work is the aluminum tube that connects the fuselage to the wings of a UAV structure, as shown in Figure 2a. This component is subjected to repeated cyclic loading during flight, which makes it highly susceptible to fatigue-induced crack nucleation. We are interested in the localized displacement responses corresponding to the region that drives the local submodel, i.e., the driving region, in Figure 2b. These embed the effects of the general complexity of the UAV assembly and the inherent variability in various structural components across the fleet.

Figure 2.

(a) UAV structure with critical component, and (b) the driving region in the vicinity of the tube.

3.2. Population Variability Definition and Dataset Generation

In a fleet of nominally identical UAVs, differences are expected to arise due to both operational (flight-related) and manufacturing variability. Flight telemetry data are routinely available through dedicated sensing systems mounted on aircraft and can be treated as known quantities. Conversely, variability induced by manufacturing processes (e.g., geometric or material variations) is typically unobserved but still influences the system response, and is therefore referred to as latent variability.

In this work, we define the conditioning vector as , where denotes the flight parameters and the structural parameters of the tube. The flight parameters include the indicated airspeed V, the angle of attack , the sideslip angle , as well as the roll p, pitch q, and yaw r rates. We have assumed that each flight parameter in the vector follows an independent uniform distribution over its prescribed range . The ranges were determined based on the range of data acquired from the test flight described in [14]. We should also note that, within the broader set of flight parameters, left and right wing flap angles were included to broaden the parameter space. However, since they take discrete values, they were excluded from the conditioning variables to prevent overfitting of the CVAE model. As for , it is fully defined by Young’s modulus and wall thickness , again assumed as: . For each parameter, the bounds of the uniform distribution were set as the nominal value plus/minus 3 standard deviations, considering a Coefficient of Variation (CoV) of 5%. These parameters were deliberately included in to enable full control in downstream tasks. On top of this, it is viewed as a solid assumption, since the tube is made of aluminum, whereas the rest of the airframe is composed of composites. Therefore, it is reasonable to treat the tube’s properties as varying independently from the rest of the structure.

Regarding latent variability, we have accounted for the structural properties of the remaining UAV components that influence the displacement response in the driving region. A sensitivity analysis was used to identify which components should be modeled stochastically. A baseline set was chosen from engineering judgment, while the rest were assessed by their effect on the conditional PDFs of translational and rotational displacements. Components that significantly broadened the PDFs were modeled stochastically; others were treated deterministically. For each composite component, the associated random vector is defined as , where , , and denote Young’s modulus, shear modulus, and laminate thickness, respectively, of the k-th component. Each parameter is modeled as an independent normal random variable with mean equal to the nominal value and fixed CoV values of 8% for and 10% for both and . The entire latent variability is then represented by the collection of K component vectors, .

Uncertainty propagation was performed using two numerical models of the reference UAV within a Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS) scheme. Specifically, a panel aerodynamic model was used to capture operational variability by sampling , and for each realization, a different pressure distribution was obtained. To account for structural variability, an FE model was then employed using and , as well as the samples of the interpolated loads. Ultimately, 2000 samples were generated from the distributions of the independent random vectors , , and , using Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS). This resulted in an equal number of displacement vectors , corresponding to 360 spatial points, each described by 6 components, i.e., 3 translational and 3 rotational .

3.3. CVAE Model Setup

The dataset was divided into training, validation, and testing sets using a 70:10:20 ratio, respectively. Convolutional branches were employed to capture spatial features of the displacement fields. For this purpose, the displacement vector was reshaped to , where the first dimension corresponds to the number of rings in the driving region; the second represents discretization along the tube’s circumference; and the third is equal to the number of displacement components.

Since each channel includes physically separate regions of the tube, the encoder employed multiple independent convolutional branches to preserve spatial integrity. Specifically, two branches consisted of 1D convolutions and two of 2D convolutions, a design motivated by the structural characteristics of the input tensor. This setup prevented mixing structurally unrelated information. The resulting features were flattened and passed through a shared multilayer perceptron (MLP), which parameterized a latent Gaussian distribution of dimension . The decoder mirrored this structure with corresponding 1D and 2D transposed convolutions to reconstruct the displacement field. Leaky ReLU activations were used in hidden layers, and a Tanh output ensured bounded responses. The network was trained with the Adam optimizer (learning rate , batch size 32) for 600 epochs with early stopping based on validation loss. Model hyperparameters were selected heuristically, and the configuration yielding the best validation performance was retained. A -weighted KL divergence, as given by Equation (4), with linear annealing was applied to balance reconstruction accuracy and latent regularization.

4. Results and Discussion

Assessing the performance of the trained CVAE surrogate requires consideration of its probabilistic nature. Unlike deterministic surrogates, the CVAE generates samples from an approximated conditional distribution, meaning that direct pointwise comparisons with the FE reference are not meaningful. Instead, the evaluation was carried out by comparing statistical descriptors of the displacement response fields across the test set. For a test set of samples, the mean and standard deviation of the FE responses are defined as in Equations (5) and (6),

with analogous expressions for the surrogate predictions in Equations (7) and (8), where latent variables are drawn from the prior distribution, concatenated with and passed through the trained decoder ,

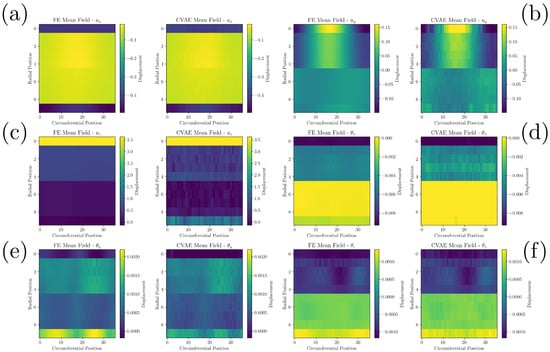

Figure 3 and Figure 4 present the mean and standard deviation fields of the six displacement components obtained from the FE model and the CVAE surrogate. The mean fields show that the surrogate is able to accurately reconstruct the global structure and magnitude of the FE predictions. Translational components are well reproduced, with the spatial gradients and peak displacements in and closely matched, while displays small localized deviations. Rotational components exhibit more variability and fine-scale differences, yet the surrogate still recovers the overall spatial organization.

Figure 3.

Contour plots of the mean fields for (a) , (b) , (c) , (d) , (e) , and (f) predicted by the FE model (left) and the surrogate (right) on the test set. All units in mm.

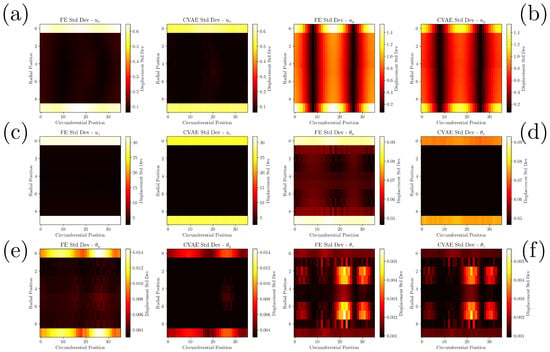

Figure 4.

Contour plots of the standard deviation fields for (a) , (b) , (c) , (d) , (e) , and (f) predicted by the FE model (left) and the surrogate (right) on the test set. All units in mm.

A similar level of agreement is observed in the comparison of standard deviation fields. The CVAE captures the dominant patterns of variability in the FE responses, with the smooth profiles of and and the characteristic circumferential striping in being reproduced with high fidelity. For the rotational degrees of freedom, the surrogate preserves the main structures of uncertainty, although some localized features, particularly in and , appear smoothed out. In the case of , the structured variability is maintained with reasonable accuracy.

Overall, the CVAE provides a robust approximation of both the mean response and the uncertainty structure of the FE model. It preserves the dominant spatial trends while avoiding artificial noise, with the largest discrepancies confined to the rotational components. These results demonstrate that the proposed surrogate can reliably capture the effects of population variability on structural responses, making it a suitable tool for probabilistic modeling in fleet-level applications. In terms of computational efficiency, generating 2000 realizations with the full-order FE model required nearly 15 h, whereas surrogate training on a GPU was completed in under six minutes. Once trained, the CVAE delivers near-instantaneous inference, producing 1000 full-field displacement predictions in less than a second, thus achieving a speed-up of several orders of magnitude over the FE model.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we introduced a CVAE surrogate that models high-dimensional response fields while capturing population variability through its predictive uncertainty. The response field corresponds to the displacements of a critical component of a UAV, which can serve as boundary conditions within submodeling schemes. The surrogate is conditioned on features monitored during operation as well as structural parameters characterizing the critical component. Results show that it successfully reproduces the spatial field patterns and enables fast, probabilistic predictions suitable for fleet-level SHM workflows. Future work on the modeling side will focus on hyperparameter optimization and sensitivity analysis, as well as the adoption of statistical divergences for rigorous probabilistic performance assessment. On the application side, a promising direction is to extend the framework to sparse-input conditioning to reflect realistic monitoring limitations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.A. and C.S.; methodology, G.A., M.G., and C.S.; software, G.A.; validation, G.A.; formal analysis, G.A.; investigation, G.A.; resources, G.A. and C.S.; data curation, G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A.; writing—review and editing, C.S.; visualization, G.A.; supervision, C.S.; project administration, M.G. and C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was conducted as part of the research project “SWARM–Digital Twin Development for HUMS of UAV Swarms”, funded by the Ministry of Defence–General Secretariat of Defence (SGD)/National Armaments Directorate (DNA), within the Agreement of Collaboration between the SGD/DNA and the Politecnico di Milano.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

DURC Statement

Current research is limited to probabilistic surrogate modeling, which is beneficial for tractable uncertainty quantification in fleet-level applications, and does not pose a threat to public health or national security. Authors acknowledge the dual-use potential of research involving probabilistic surrogate modeling and confirm that all necessary precautions have been taken to prevent potential misuse. As an ethical responsibility, authors strictly adhere to relevant national and international laws about DURC. Authors advocate for responsible deployment, ethical considerations, regulatory compliance, and transparent reporting to mitigate misuse risks and foster beneficial outcomes.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this study, the authors used ChatGPT 5 for the purposes of checking spelling, grammar, and syntax errors and improving readability. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Farrar, C.R.; Worden, K. An introduction to structural health monitoring. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2007, 365, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.C. Uncertainty Quantification: Theory, Implementation, and Applications; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Mclean, J.H.; Jones, M.R.; O’Connell, B.J.; Maguire, A.E.; Rogers, T.J. Physically meaningful uncertainty quantification in probabilistic wind turbine power curve models as a damage-sensitive feature. Struct. Health Monit. 2023, 22, 3623–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, L.A.; Gardner, P.A.; Gosliga, J.; Rogers, T.J.; Dervilis, N.; Cross, E.J.; Papatheou, E.; Maguire, A.E.; Campos, C.; Worden, K. Foundations of population-based SHM, Part I: Homogeneous populations and forms. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 148, 107141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bao, T.; Chen, Z.; Gao, Z.; Shu, X.; Zhang, K. A missing sensor measurement data reconstruction framework powered by multi-task Gaussian process regression for dam structural health monitoring systems. Measurement 2021, 186, 110085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, M.A.; Todd, M.D. A variational Bayesian neural network for structural health monitoring and cost-informed decision-making in miter gates. Struct. Health Monit. 2020, 21, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkem, Y.; Biswas, S.K.; Varanasi, A. A comprehensive review of synthetic data generation in smart farming by using variational autoencoder and generative adversarial network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 131, 107881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Cheng, S.; Duraisamy, K. Spatially-aware diffusion models with cross-attention for global field reconstruction with sparse observations. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2025, 435, 117623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białas, P.; Korcyl, P.; Stebel, T. Training normalizing flows with computationally intensive target probability distributions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2024, 298, 109094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoi, T.; Amishiki, K.; Lee, S.; Yaoyama, T. Bayesian structural model updating with multimodal variational autoencoder. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2024, 429, 117148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonas, C.; Abdallah, I.; Chatzi, E. Conditional variational autoencoders for probabilistic wind turbine blade fatigue estimation using Supervisory, Control, and Data Acquisition data. Wind Energy 2021, 24, 1122–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachas, K.; Simpson, T.; Garland, A.; Quinn, D.; Farhat, C.; Chatzi, E. Reduced Order Modeling conditioned on monitored features for response and error bounds estimation in engineered systems. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 226, 112261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silionis, N.E.; Liangou, T.; Anyfantis, K.N. Deep learning-based surrogate models for spatial field solution reconstruction and uncertainty quantification in Structural Health Monitoring applications. Comput. Struct. 2024, 301, 107462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Dong, L.; Dziendzikowski, M.; Dragan, K.; Giglio, M.; Sbarufatti, C. Real-Time In-Service Load Tracking Toward Airframe Digital Twins. AIAA J. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).