Digital Transformation Meets Process Improvement: Driving Enterprise Continuous Efficiency-Seeking †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Scope and Definitions

“an organized, measurable set of activities aimed at producing a specific output for a specific customer or market. The business process puts a lot of pressure on how work is done within an organization as opposed to a product-centric emphasis. A process is therefore a specific order of activities defined in time and space, with a definite beginning and end on clearly specified inputs and outputs: the structure of the action. A process approach means that the organization adopts the customer’s point of view. Processes are the structures by which an organization does what is necessary to create value for its customers”.[1]

“A process is an approach for converting inputs into outputs. It is the way in which all the resources of an organization are used in a reliable, repeatable and consistent way to achieve its goals”.[2]

“Digital transformation is the use of new digital technologies such as social media, mobile technology, analytics, or embedded devices to enable major business improvements including enhanced customer experiences, streamlined operations, or new business models”.[5]

“Digital transformation is the combined effects of several digital innovations bringing about novel actors (and actor constellations), structures, practices, values, and beliefs that change, threaten, replace, or complement existing rules of the game within organizations, ecosystems, industries, or fields”.[5]

- User and customer experience

- Corporate culture

- Ecosystem

- Processes (assessment and improvement)

- Process improvement very often means digitization;

- Measuring performance (i.e., the gap between design and execution) is much easier and more reliable using digital tools and methods;

- The measures taken throughout the course of time are very useful data for analysis and prediction using AI.

3. Business Process Improvement

3.1. 5S Technique

- Accumulation of unnecessary items;

- Contamination of machines or materials;

- Breakdown of procedures.

3.2. Kaizen

- PDCA: Plan-Do-Check-Act or Deming wheel for continuous improvement;

- PDSA: Plan-Do-Study-Act, where, in the study step, we go deeper in the process of analyzing things instead of checking and passing by;

- DMAIC: Define-Measure-Analyze-Improve-Control.

3.3. Lean

“It provides a way to specify value, line up value-creating actions in the best sequence, conduct these activities without interruption whenever someone requests them, and perform them more and more effectively. In short, lean thinking is lean because it provides a way to do more and more with less and less human effort, less equipment, less time, and less space—while coming closer and closer to providing customers with exactly what they want”.[12]

- Identify Value: Value is what the customer is willing to pay for. Sometimes customers do not know what they want or how to express it. Many techniques could be used to help the customers at this end such as interviews, surveys, and web analysis.

- Map the Value Stream: The goal of this step is to use the customer’s value as a reference point to identify all the activities that contribute to these values. Activities that do not add value to the end customer are considered waste.

- Create a Flow: After removing the waste from the value stream, the following actions are meant to ensure that the flow of the remaining steps run smoothly without interruptions or delays. Some strategies for ensuring that value-adding activities flow smoothly include breaking down steps, reconfiguring the production steps, leveling out the workload, creating cross-functional departments, and training employees to be multi-skilled and adaptive.

- Establish a Pull System: Inventory is considered one of the biggest wastes in any production system. The goal of a pull-based system is to limit inventory and work in process (WIP) items while ensuring that the requisite materials and information are available for a smooth flow of work.

- Seek Continuous Improvement: Pursuing continuous perfection is a key step because it makes lean thinking and continuous process improvement a part of the organizational culture.

3.4. Six Sigma

- Define: Outline problems and issues within the process from both the business and client perspectives;

- Measure: Narrowing of the project focus occurs, and baseline data are collected;

- Analyze: Data are examined to help identify the root cause of an issue and help remove inefficiencies;

- Improve: Establish ways to improve the process and correct deficits. The improve phase may include solution brainstorming, evaluation, and optimization, as well as an implementation plan;

- Control: Monitor and maintain the solution.

3.5. A Comparative View

4. The Digital Transformation Perspective

4.1. The Maturity Assessment

- Capability-Based Assessments: McKinsey Digital Maturity Model, Accenture’s Digital Maturity Framework, Bain & Company’s Digital Maturity Diagnostic;

- Strategic and Organizational Assessments: Gartner’s Digital Maturity Model, Deloitte’s Digital Maturity Model, Boston Consulting Group (BCG) Digital Maturity;

- Technology-Centric Maturity Models: Forrester’s Digital Maturity Model, Microsoft’s Digital Transformation Framework;

- Customer-Centric Models: Capgemini’s Digital Maturity Framework, PwC’s Digital Maturity Assessment;

- Process-Oriented Models: SAP’s Digital Transformation Framework, IBM’s Digital Transformation Assessment;

- Comprehensive, Multi-Dimensional Models: The Digital Capability Framework by TCS Benchmarking and Comparative Models, EY’s Digital Maturity Index (DMI);

- Benchmarking and Comparative Models: McKinsey & Company Digital Quotient (DQ), Accenture’s Digital Benchmarking.

- Strategy and Leadership: Focuses on the vision, commitment, and leadership for digital transformation.

- Technology and Infrastructure: Includes the adoption of cloud, AI, IoT, and other emerging technologies.

- Customer Experience: Looks at how digital solutions enhance customer interactions and relationships.

- Data and Analytics: Evaluates an organization’s data capabilities, data-driven decision-making, and analytics maturity.

- Culture and Organization: Assesses how organizational culture supports digital adoption, collaboration, and innovation.

- Operations and Processes: Focuses on process optimization through digital technologies like automation, AI, and business process management (BPM).

- Surveys and Questionnaires: Many firms use structured surveys or questionnaires to collect data on the organization’s digital maturity across various domains.

- Interviews and Workshops: Personal interviews and collaborative workshops help gather deeper insights from key stakeholders across the organization.

- Quantitative Scoring Systems: Maturity models often use scoring systems to rate an organization’s maturity across each dimension.

4.2. Digital Transformation Improvement Effects

- Improved quality and reduced costs;

- Increased agility;

- Increased profits;

- Digital culture development.

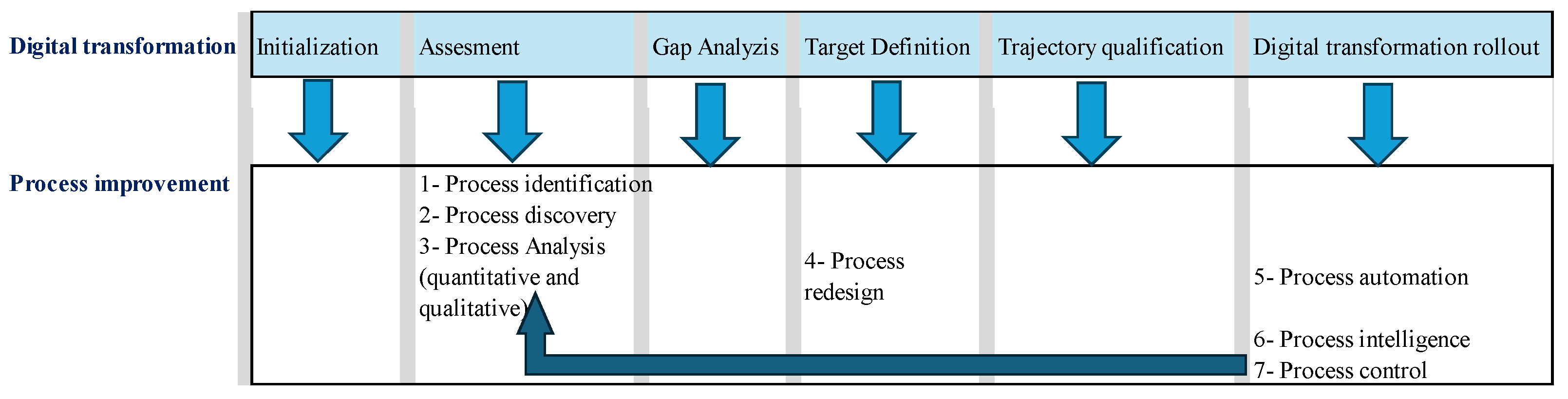

4.3. Digital Transformation vs. Process Improvement

- Lack of an integrated conceptual framework to lead in an optimal way simultaneously with the digital transformation and the process improvement;

- A wrong priority choice, for the processes, when it comes to rollout digital transformation, may lead to unexpected outcomes;

- The timeframe for digital transformation is wider than for process improvement;

- The change management scope is much bigger for digital transformation than for process improvement.

5. Conclusions

- More efficient in certain fields of business/management (manufacturing for instance);

- Hard to deploy fully (going through all steps) when the time is a constraint, and results should be reached very fast;

- Cover just part of the need so the practitioners should sometimes mix methods to obtain the expected outcomes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Senkus, P.; Glabiszewski, W.; Wysokinska-Senkus, A.; Panka, A. Process Definitions—Critical Literature Review. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, 24, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zairi, M. Business process management: A boundaryless approach to modern competitiveness. Bus. Process Manag. J. 1997, 3, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocke, J.V.; Rosemann, M. Handbook on Business Process Management 1: Introduction, Methods, and Information Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deming, W.E. Out of the Crisis; MIT Press Series; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.; Jones, P.; Kailer, N.; Weinmann, A.; Chaparro-Banegas, N.; Roig-Tierno, N. Digital Transformation: An Overview of the Current State of the Art of Research. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211047576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, P.B. Quality is Free: The Art of Making Quality Certain; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, K. Guide to Quality Control; Asian Productivity Organization: Tokyo, Japan, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Juran, J.M. Juran’s Quality Control Handbook, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Feigenbaum, A.V. Total Quality Control, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Beno, J.; Rao, M.V.; Beno, J.; Das, S.K. Process Control & Inspection using 5s Method and Computation with Pareto Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication, and Control (ICAC3), Mumbai, India, 3–4 December 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Beltrán, J.C.C.; Llanos-Ramírez, M.D.C.; Ramírez-Jiménez, A.; Bogarin-Correa, M.R. Educational innovation: An approach to the Japanese Kaizen method in university students. Reflections and perspectives. J. Educ. Theory/Rev. Teoría Educ. 2024, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womack, J.P.; Jones, D.T. Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; p. 402. [Google Scholar]

- Six Sigma Revealed. Available online: https://www.sixsigma-institute.org/contents/Six_Sigma_Revealed_by_International_Six_Sigma_Institute.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Van de Ven, A.H.; Poole, M.S. Explaining development and change in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 510–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschalk, P. Maturity levels for interoperability in digital government. Gov. Inf. Q. 2009, 26, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanjian, R.K.; Drazin, R. A stage-contingent model of design and growth for technology based new ventures. J. Bus. Ventur. 1990, 5, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, A.M.; Moultrie, J.; Clarkson, P.J. Assessing Organizational Capabilities: Reviewing and Guiding the Development of Maturity Grids. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2012, 59, 138–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Focus | Pros | Cons | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5S | Work Environment |

|

|

| Kaizen | Culture |

|

|

| Lean | Waste |

|

|

| Six Sigma | Defects and quality |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ouradi, N.; Saidi, R.; Cherif, W. Digital Transformation Meets Process Improvement: Driving Enterprise Continuous Efficiency-Seeking. Eng. Proc. 2025, 112, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025112077

Ouradi N, Saidi R, Cherif W. Digital Transformation Meets Process Improvement: Driving Enterprise Continuous Efficiency-Seeking. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 112(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025112077

Chicago/Turabian StyleOuradi, Najib, Rajaa Saidi, and Walid Cherif. 2025. "Digital Transformation Meets Process Improvement: Driving Enterprise Continuous Efficiency-Seeking" Engineering Proceedings 112, no. 1: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025112077

APA StyleOuradi, N., Saidi, R., & Cherif, W. (2025). Digital Transformation Meets Process Improvement: Driving Enterprise Continuous Efficiency-Seeking. Engineering Proceedings, 112(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025112077