Abstract

Health monitoring systems play a crucial role in every life. In the 21st century, advanced technologies like wearable sensors have emerged and make healthcare better overall. These sensors collect massive amounts of data about our health over time in many dimensions. In this paper, our objective is to develop and evaluate a machine learning-based clinical decision support system using wearable sensor data to accurately classify users’ physiological states and activity contexts. The most accurate and effective model is for identifying wearable sensor-based physiological signal classification. However, there are serious privacy and security issues with sending raw sensor data to centralized computers. We gathered the multivariate physiological and activity data from wearable technology, including smartwatches and fitness trackers, which make up the dataset. Physiological signals, including heart rate, resting heart rate, normalized heart rate, entropy of heart rate variability, and caloric expenditure, are all included in the dataset. Lying, sitting, self-paced walking, and running at different MET(Metabolic Equivalent of Task) levels are examples of activity context labels. To secure our data, we proposed an architecture based on federated learning that helps machine learning model training across several dispersed devices without exchanging raw data. In this study, we used eight classifiers, and these are XGBoost, RF, Extra Trees, LightGBM, CatBoost, Bagging, DT, and GB. It has been observed that XGBoost performs well in comparison to the other classifiers with an accuracy of 0.94, a precision of 0.90, a recall of 0.89, an F1-score of 0.90, and an AUC-ROC of 0.98. This study demonstrates the potential of wearable sensor data, combined with machine learning, for accurately classifying activity and physiological conditions. The ML boosting family, especially XGBoost, exhibited strong generalization across diverse signal inputs and activity contexts. These results suggest that explainable, non-invasive wearable analytics can support early detection and monitoring frameworks in personalized healthcare systems. The proposed federated learning framework effectively combines privacy-aware computation and accurate classification using wearable sensor data.

1. Introduction

In the 21st century, most people wear wearable sensor devices to monitor their health conditions. These sensor devices continuously track changes in the body such as blood pressure, body temperature, heart rate, and other physical activities. Each piece of data is to be treated as important for well-being. To detect early disease, these sensors play a vital role. These devices not only detect the diseases but also manage and give personalized treatment advice. In today’s scenario, AI plays a vital role in many fields such as mobile computing, IoT, healthcare, finance, etc. In particular, machine learning and deep learning play a dramatic role in the healthcare industry. However, there are significant privacy hazards associated with gathering and processing this data in one place. People may be at risk of identity theft, data breaches, and exploitation of their private health information. The data is collected from different sources and stored in a single location before training. The abundance of centralized training data has been a major factor in the development of deep learning and ensemble approaches over the last ten years. However, there are significant privacy, security, and compliance problems associated with the conventional centralized paradigm of machine learning, which aggregates raw data from dispersed sources into a single data center. To overcome these issues, federated learning (FL) has emerged as a potential paradigm for training machine learning models in a distributed manner. FL enables collaborative model training via dispersed devices while keeping raw data localized, ensuring user privacy. In the context of wearable health monitoring, FL enables several users to contribute to a shared global model while keeping their personal sensor data private. This new concept emerged and is called the FL (federated learning) environment, where the models are trained without the raw data. In this approach, we trained the model locally, and we have not shared the raw data with the central server. Only the estimated weights and biases are sent to the central server. Then the server combines all the different clients’ data and aggregates it, as well as creates a global model. This approach helps to protect the data and allows learning from a distributed model. This study proposed a framework, called privacy-preserving health monitoring, that allows the FL techniques to analyze the wearable sensor data. Here, data is of the utmost priority, including its confidentiality and security.

1.1. Research Objectives and Questions

In this paper, our main objective is to analyze the wearable sensors’ data and estimate the privacy-preserving techniques on the ensemble models in federated learning. To handle the above-mentioned research objective, we have the following research questions to address:

- Can communication-efficient algorithms (like DP-FedAvg or SCAFFOLD) sustain performance across weak learners (e.g., Decision Tree) while enhancing privacy and reducing variance?

- How does model complexity influence the performance drop when transitioning from centralized to federated learning?

1.2. Contributions of the Paper

The following key contributions are discussed in the subsequent sections:

- In this paper, we have used the eight ensemble learning models for both centralized as well as federated learning. Here we estimated results with and without a privacy mechanism.

- We estimated the AUC-ε and Accuracy-ε–ε curves and discuss how privacy budgets affect performance across the different algorithms (FedAvg, DP-FedAvg, FedProx, and SCAFFOLD).

2. Related Work

Federated learning is used in many domains such as agriculture, healthcare etc. Das, S. et al. [1] developed a model that allows for the early detection of disease using federated learning. The author was focused on data privacy by decentralizing data. They collected sensor data from different sources and used FL to achieve the task. Aminifar, A. et al. [2] proposed a framework that allows for a secure mechanism using privacy-preserving edge federated learning. This framework is specially designed for mobile health technologies. Wang, W. et al. [3] presented a model called FRESH that allows the collection of physiological data using different sensors. These data are analyzed by edge computing devices (such as mobile phones and tablet PCs), which train ML models on local data. Edge computing devices submit model parameters to the central server for the cooperative training of FL illness prediction models. A framework was proposed for a smart healthcare system using FL. The authors Mishra, A. et al. [4] intended to secure the data. The authors collected data from different IoT environments. The collected data was trained locally, and the sensitive data was not sent to the central server to ensure the patients’ data was secure. Arikumar, K.S. et al. [5] proposed a framework that utilized FL and DL models for identifying a person’s movement. The author collected the data from different wearable devices and tracked the person’s movement. The author used a BiLSTM and obtained an accuracy score of 99.67%. Ghosh, S. et al. [6] developed the FEEL framework that helps to detect early disease, where the data comes from the real-time environment. This framework was developed through FL models to ensure data privacy and security. The author achieved an accuracy and F1-score of 0.86 to 0.94. Zhang, F. et al. [7] used FL algorithms to handle healthcare issues. The data that they considered was class imbalance, required distributed optimization, etc. The Scopus data was reviewed from 2015 to 2023, and a new FL methodology was proposed that helps to solve the challenges in the healthcare industry. Akhmetov, A. et al. [8] used FL models and compared them with a centralized model. The performance metrics, such as accuracy, precision, recall, and AUC-ROC, were used to determine which model was the best. The authors collected the data from different sensors and developed the solution, which works for both regression and classification approaches. The proposed model was developed, using centralized and federated learning models, to achieve the task. For handling the regression, the MAR, MSE, and RMSE were estimated, and they finally developed an FHIR-integrated federated learning platform that allows a privacy-preserving ecosystem to optimize the health data.

3. Proposed Model for Secure Health Data Aggregation and Prediction Through Federated Learning

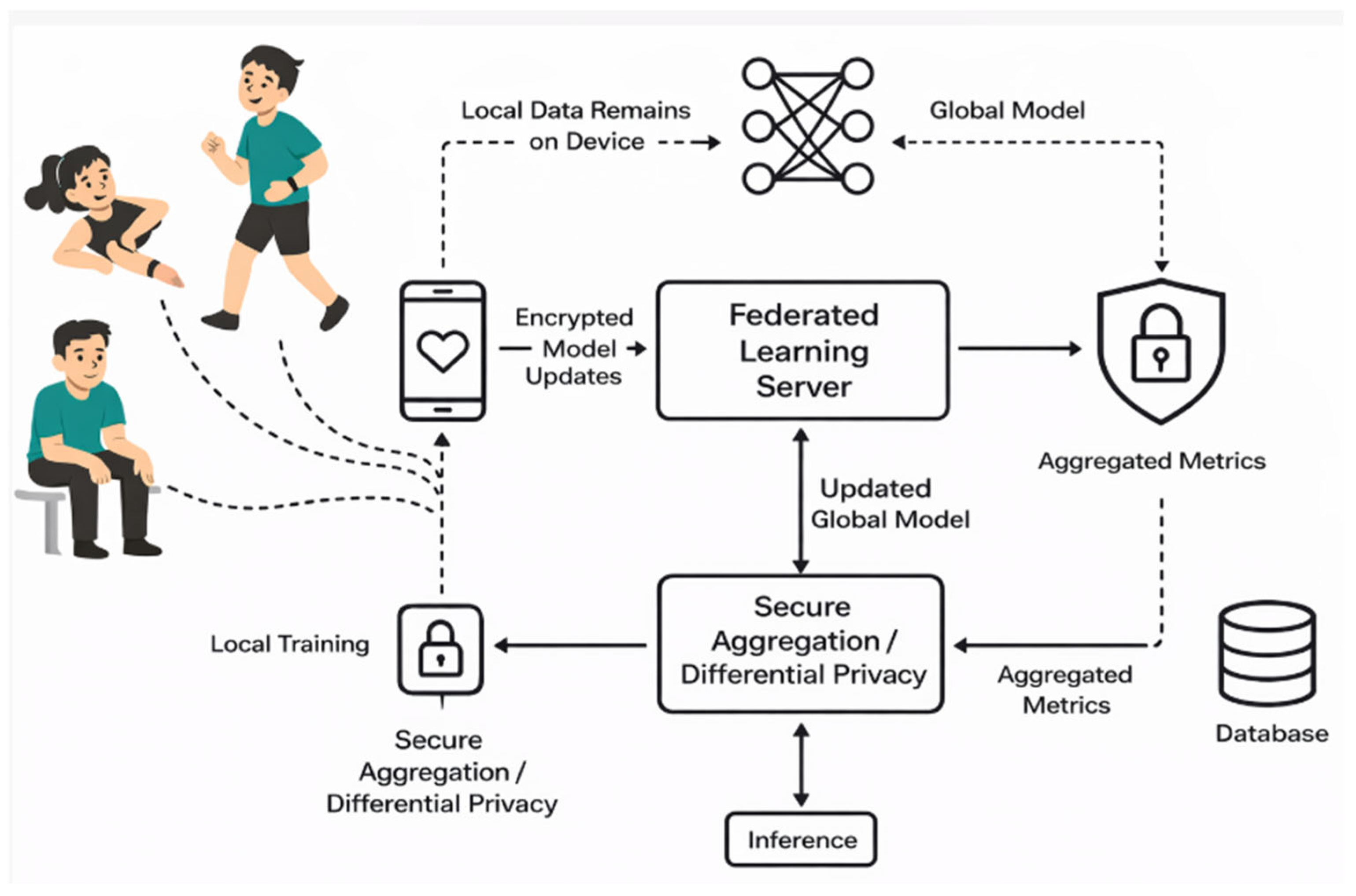

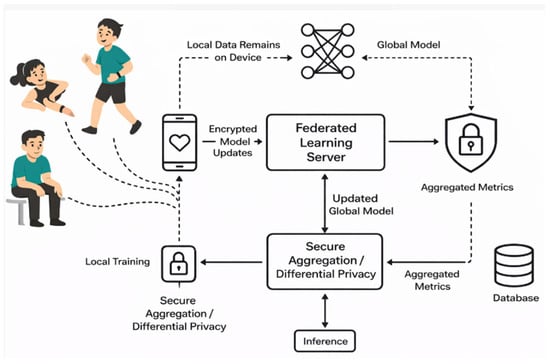

Figure 1 represents the proposed model for secure health data aggregation and prediction through federated learning. This model gives a systematic approach for secure health data aggregation and prediction through federated learning models. This model employs the eight algorithms without providing the sensitive data. It only gives the W (weight) and B (bias) to the central server. Different sensors are used to collect the data. This study collects the physiological, activity, and demographic data. Each client trains the model on the raw data but will not share the sensitive information. They share the encrypted data with the central aggregation server.

Figure 1.

Proposed model for secure health data aggregation and prediction through federated learning.

Phase 1: In this phase, we collected the data from the different sources like- smart watches, fitness bands, etc. and prepared the dataset. The different signals were captured. For physiological signals, we focused on heart rate, resting heart rate, calories, etc. Similarly, for activity context, we focused on how a person is sitting, lying, walking, going, etc. For derived features, we tried to find the correlation between the features, like how steps and heart rate were correlated, etc. Age, gender, and height as well as weight were also considered for demographic purposes. Our objective was to gather various relevant features from different users to enable personalized health monitoring. We then split the dataset into N parts. Here, each part was treated as a client. We trained each model on centralized data and estimated the performance metrics for all the models. The dataset used in this study comprises continuous physiological measurements obtained from wearable sensor devices, including heart rate, BP, physical activity level, etc. These metrics were chosen because of their proven clinical value in the early identification and tracking of cardiovascular illnesses (CVDs), including heart failure, hypertension, and arrhythmia. To preserve participant privacy, all measures were anonymized and gathered across several sessions to record both active and resting phases. For use in the federated learning experiment, the dataset was preprocessed to eliminate noise, deal with missing values, and standardize measurements. Phase 2: In this phase, the clients (devices) performed the preprocessing task to obtain data privacy. In this phase, we performed data normalization, feature engineering, etc. and finally we obtained the clean data. Our objective was to create a model for training our raw data without sending our raw data to the central server. Phase 3: In this phase all the clients trained the traditional machine learning models on their data. All models were trained independently, but they did not send any sensitive data to the server. Specifically, they sent the weight and bias because the clients want to protect their data above all. The traditional common models are XGB, RF, ET, LightGBM, CatBoost, etc. In this module, our objective was to preserve the data while preparing the models through traditional ML. Phase 4: In this phase, the weight and bias sent from the local devices were estimated by the aggregates, which are called FedAvg. Here the model updates without compromising data privacy. Once the model was updated, the encrypted data was sent to the server for further processing because data security and privacy are the main concerns. The main objective was to protect the sensitive data so that no one can attack the models. Phase 5: Aggregation Model: The objective of the aggregation server was to update the coordinates without sharing the raw (original data). The weight and bias needed to be updated using the function:

In the above equation, wi is the model, i is the client, ni is the size of the local data, and n is the total data received from all the devices. Once the model is updated, then it sent back to the client.

We continued to train the model throughout numerous federated rounds to increase overall performance.

For iterative rounds, we developed the mathematical model up to T rounds.

Di is the client machine’s model.

Finally, we needed to update the final global model for the final prediction purpose.

where

- : Trained ML model (e.g., CNN, LSTM).

- : Final learned weights after T rounds.

4. Results and Discussion

Table 1 discusses the performance evaluation of the eight-classification task for wearable sensor data. We used four performance metrics, and these were the Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-Score, and ROC-AUC. These were used to detect early diseases through the collected sensor data. These metrics were used to determine which classification model is best for identifying early diseases. It has been observed that the XGBoost model performed well in comparison to other models. It obtained the highest accuracy of 94.53%. The attained F1-score of 0.90 demonstrates the good balance between the other two metrics, i.e., precision and recall. The obtained ROC-AUC score of 0.98 means that through AUC-ROC we have classified the positive and negative classes perfectly. Our results also demonstrate that the ensemble learning-based model (XGB) is the best model for the healthcare domain, optimizing the trade-off between accuracy and P-R as well as class separation capability through the AUC-ROC curve.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of different machine learning models for early disease detection through sensor data.

Table 2 presents the comparison between centralized training and federated learning. We employed eight machine learning algorithms and compared them with each other, as well as performing 50 communication rounds. We compared these two approaches so as to find out which approach is suitable for early disease detection using sensory-collected data. During comparison, we observed that the centralized model performed well, as well as consistently higher than the federated learning environment. We observed a 1–2% drop in the performance between them because the data remains distributed.

Table 2.

Performance comparison: federated learning vs. centralized training.

Table 3 presents the best algorithm, DP-FedAvg. It has been observed that the best algorithm of the centralized model is XGB and the best FL model is XGBoost (0.9321 ± 0.005). Here, the performance is doped due to the communication round, and the data is distributed. But we have seen that the models GB and DT have larger relative drops, about 1.4–1.7%. The centralized model is good because it uses the complete raw data directly. The FL model is a little bit less good but provides more data privacy, which is most important in the healthcare domain. DP-FedAvg wins with federated XGBoost (0.9321 ± 0.005, ε = 1.2); the accuracy loss is only about 1.3% as compared to the centralized model, it keeps a high ROC-AUC of 0.981 ± 0.003, and it operates under strict privacy protections. XGBoost + DP-FedAvg is the best overall model–model algorithm pair; it has the highest accuracy (0.932 ± 0.005) in the whole of Table 2. This is consistent with previous tables showing that XGBoost is the most reliable and effective model in both federated and centralized environments.

Table 3.

FL algorithm comparison.

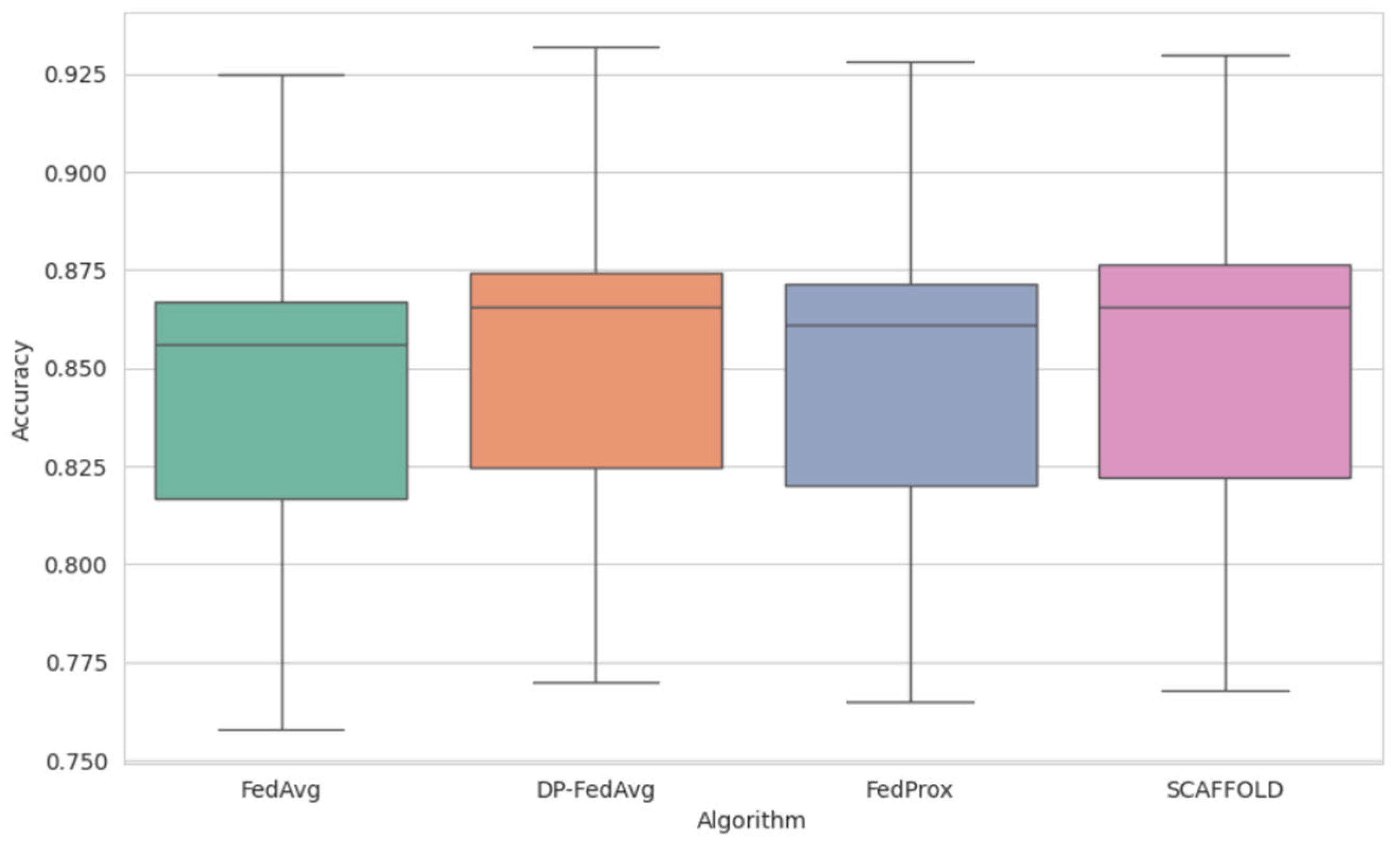

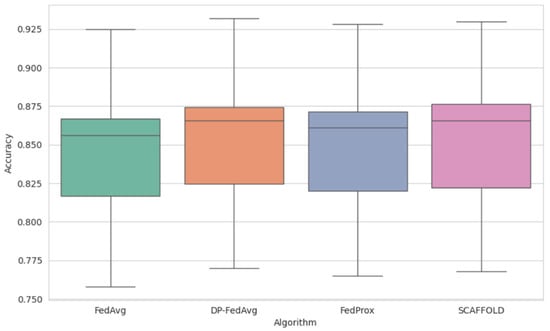

Figure 2 represents the mean accuracy across the models. We have estimated the mean accuracy of the models and found that the FL model DP-FedAvg obtained 0.85, which is higher as compared to the other models. In Figure 2, P-FedAvg is 0.932, which is better than all the other models.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the mean accuracy of different FL models.

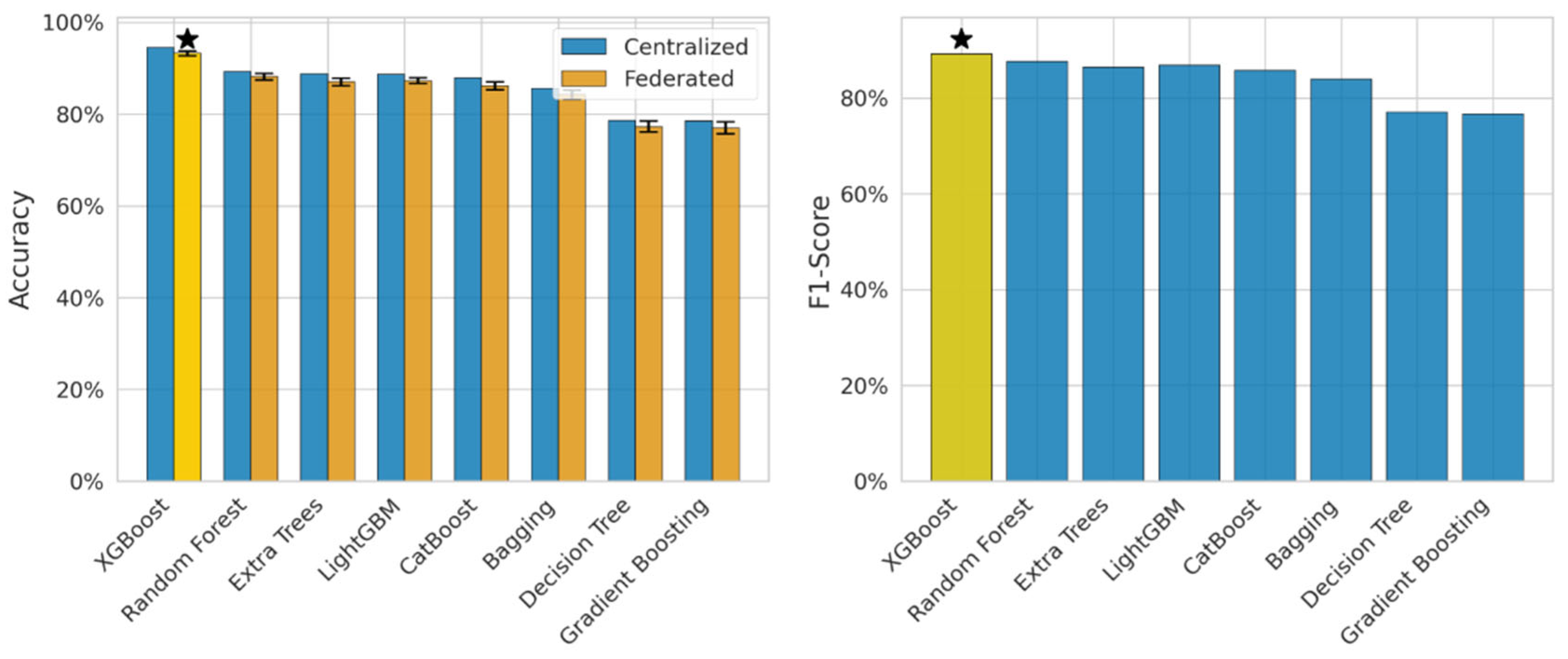

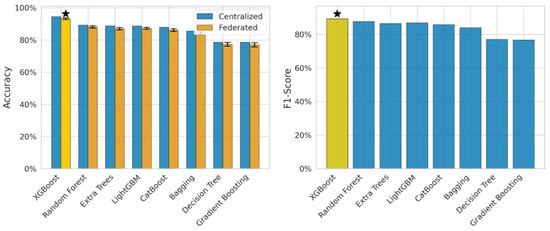

Figure 3 presents the comparison of centralized and federated learning models and emphasizes the performance metrics, accuracy, and F1-score. It has been observed that XGBoost performed well in centralized as well as federated environments, i.e., the decrease varies from 1 to 3%. The centralized model, XGB, obtained 94.5% and the FL model obtained 93.2 ± 0.5%. This marks the best-performing model and indicates that the model is suitable for federated health data. The above-mentioned figure discusses how FL impacts the models and establishes the relationship between precision and recall. The XGBoost model obtained an F1-score of 0.89, which helps handle the class imbalance issues. We used four FL algorithms to achieve the early diagnosis from the sensor data, and these algorithms were FedAvg, DP-FedAvg, FedProx, and SCAFFOLD. Experimental work revealed that DP-FedAvg performs well for privacy-sensitive data. The yellow shaded bars represents the proposed hybrid model. It is used for comparison of the individual models. The yellow bar presents the highest accuracy obtained through the proposed model. The right hand side plot designates for F1-score and the yellow bar presents the best F1-score.

Figure 3.

Accuracy and F1-comparison between centralized and federated learning.

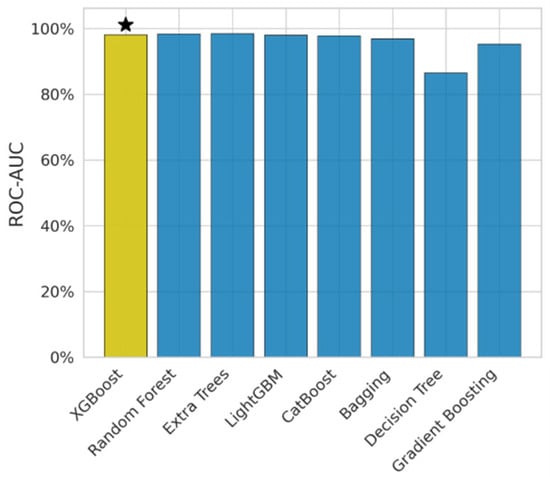

In Figure 4, AUC-ROC exhibits the discriminative power of the model. It has been observed that DT obtained 0.86, which is less than other models. The Extra Trees model obtained the highest AUC score of 0.98. The XGB model’s AUC score is 0.98, i.e., it is the balanced model.

Figure 4.

Federated learning AUC score.

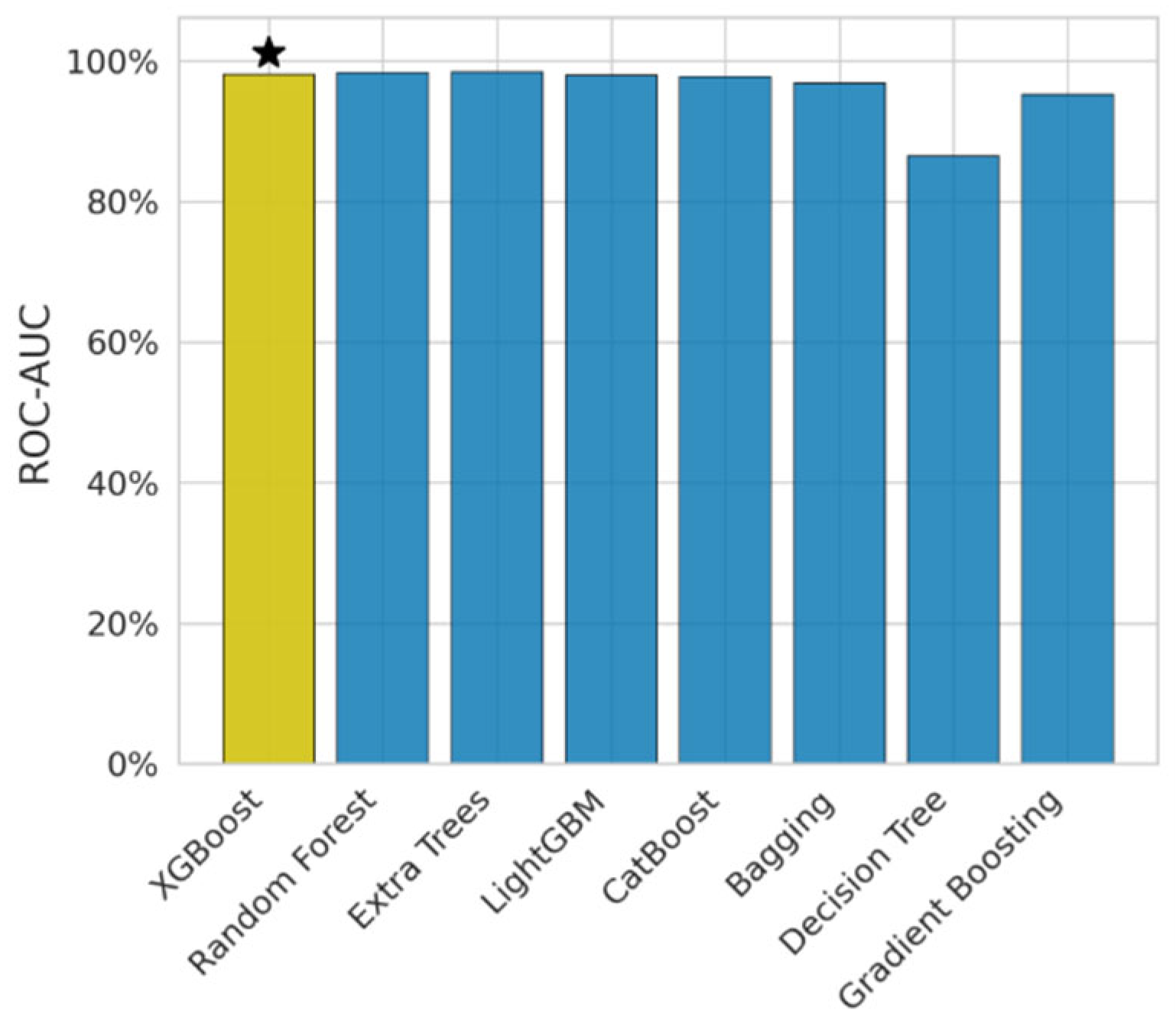

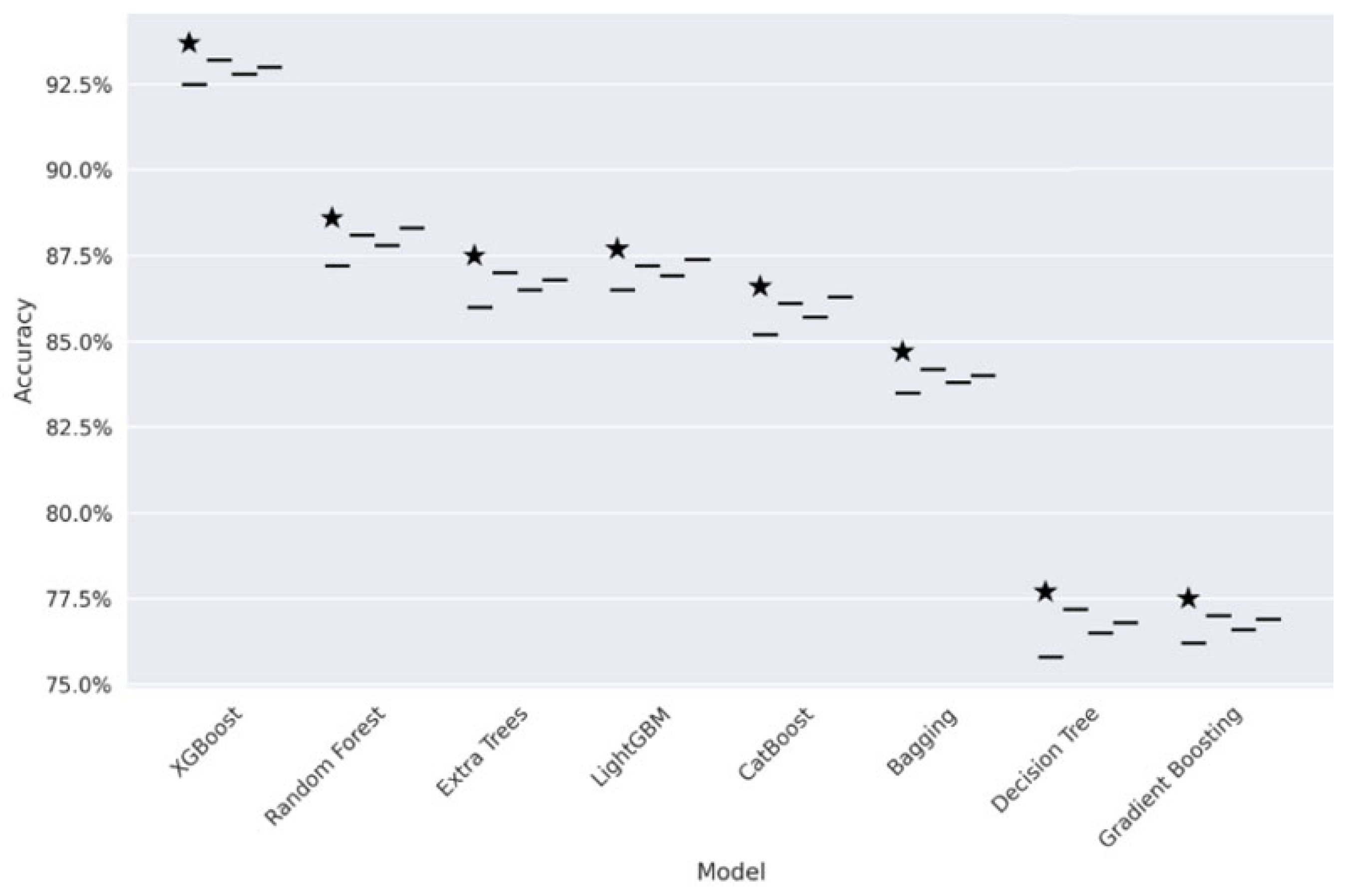

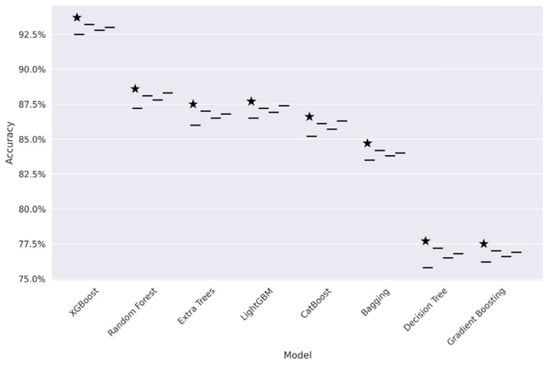

Figure 5 presents the comparative study of FL models’ performance. We conducted a performance analysis of all the tree-based algorithms in privacy-constrained environments. It has been observed that DP-FedAvg obtained the highest median accuracy (93.2% for XGBoost). The model obtained the lowest minimal variance (±0.5%) while considering FedAvg, FedProx, and SCAFFOLD across all models. The star represents the highest score.

Figure 5.

Comparative study of FL models.

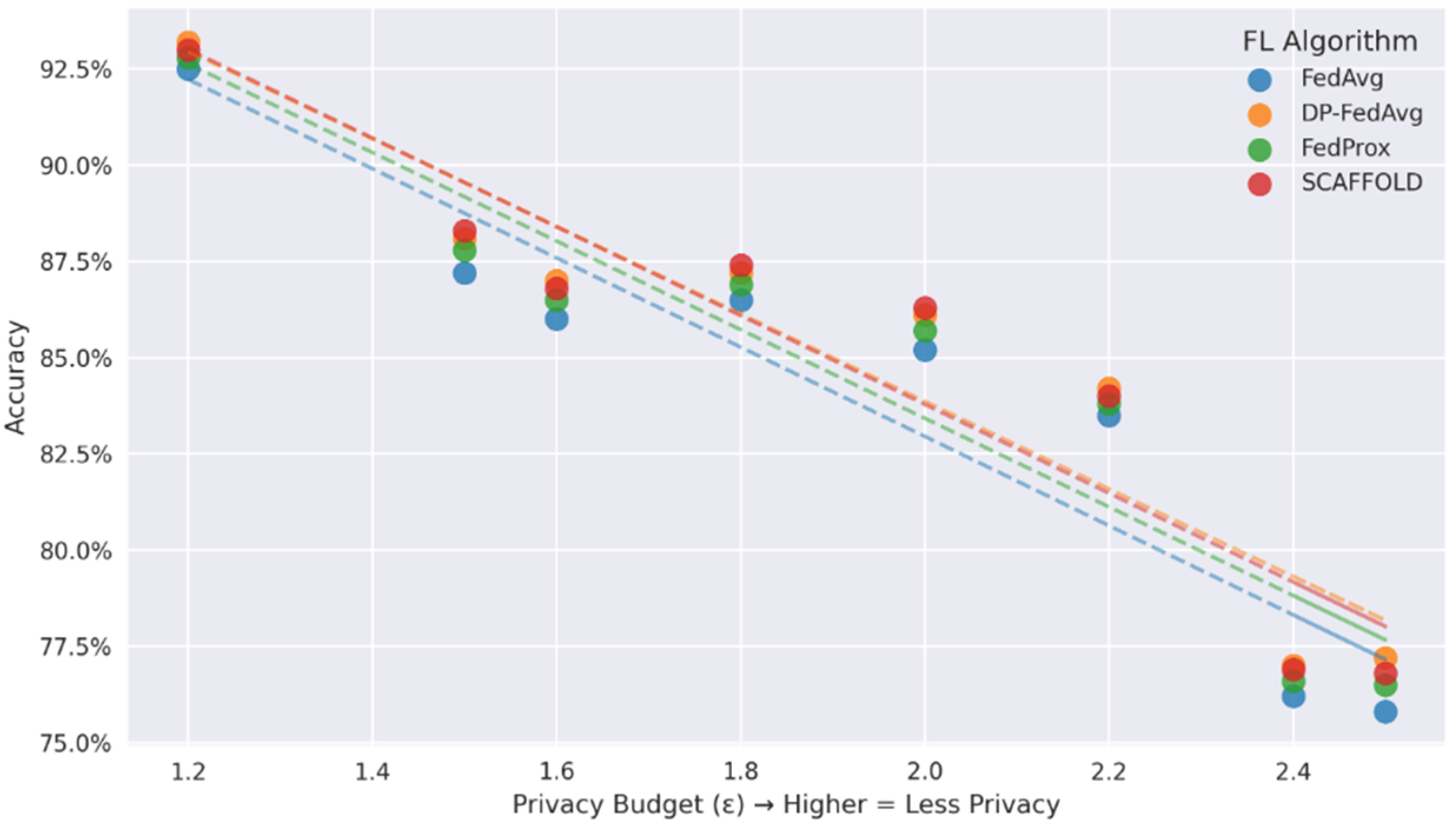

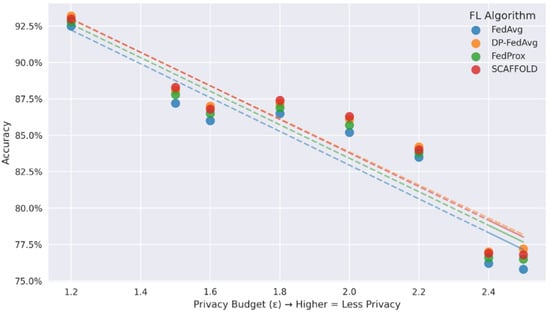

In Figure 6, DP-FedAvg maintains >92% accuracy even at severe privacy budgets (ε = 1.2–1.8), while other algorithms exhibit sharper accuracy deterioration (FedAvg: −2.1% and SCAFFOLD: −1.7% at ε = 1.5). Subplot (b) analyses the privacy–accuracy trade-off. The trend lines showing a negative correlation between accuracy and ε, which validates that DP-FedAvg strikes the optimal compromise between model utility and differentiated privacy guarantees. All of these findings point to DP-FedAvg as the best option for federated health applications.

Figure 6.

Relationship between privacy budgets and accuracy.

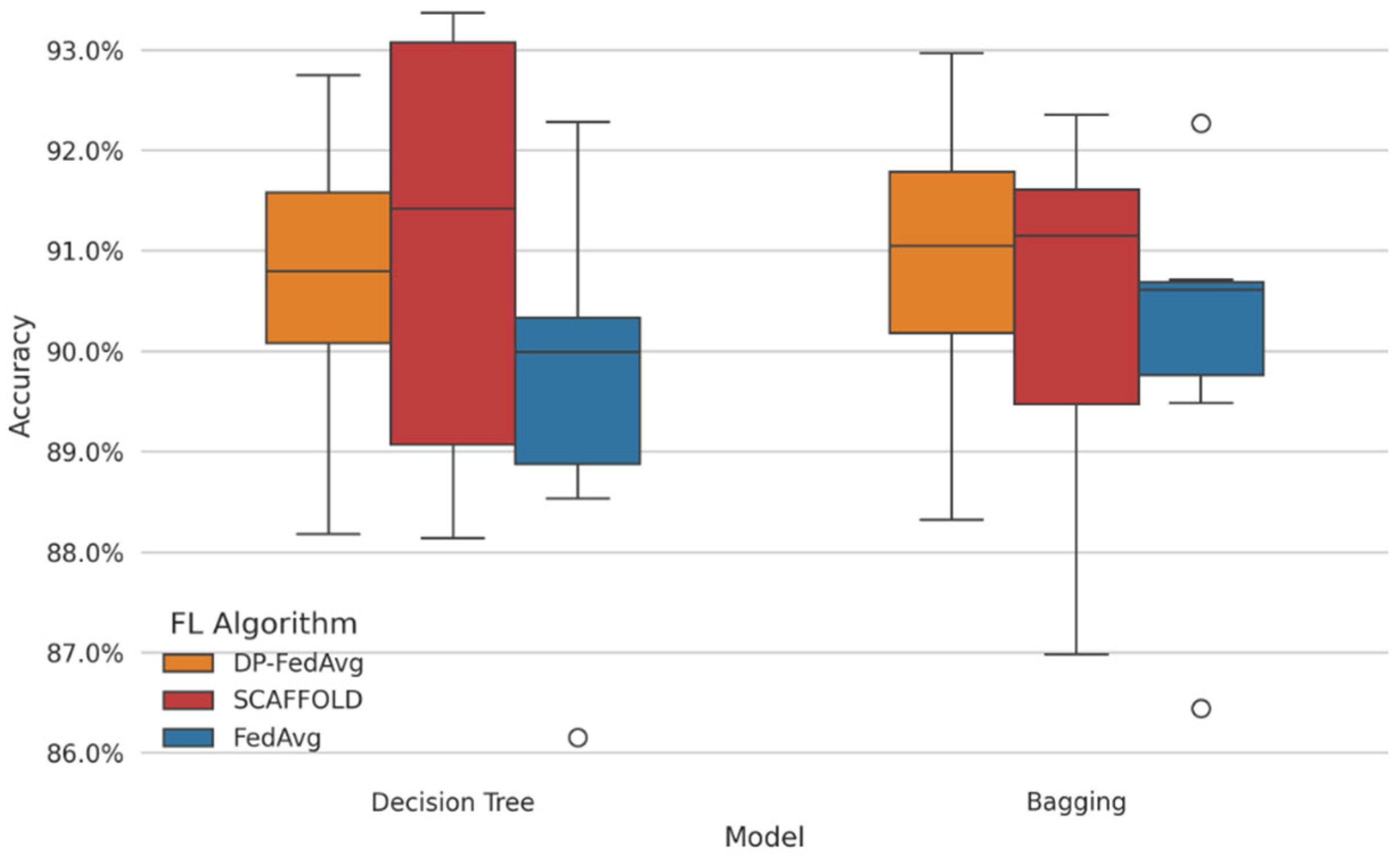

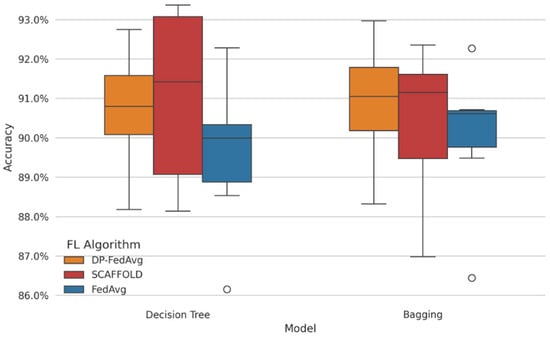

RQ1.

Can communication-efficient algorithms (like DP-FedAvg or SCAFFOLD) sustain performance across weak learners (e.g., Decision Tree) while enhancing privacy and reducing variance?

Figure 7 presents the comparative analysis between centralized and federated learning. Here we have plotted a graph of accuracy and F1-score across different machine learning models. This model suggests that XGBoost is the best performer in the Fl environment, with an accuracy of 94.53% and F1-score of 0.90. This indicates that federated learning can successfully maintain user privacy while maintaining speed, particularly in healthcare contexts, where sensitivity concerns make data centralization impractical.

Figure 7.

Accuracy comparison for weak learners.

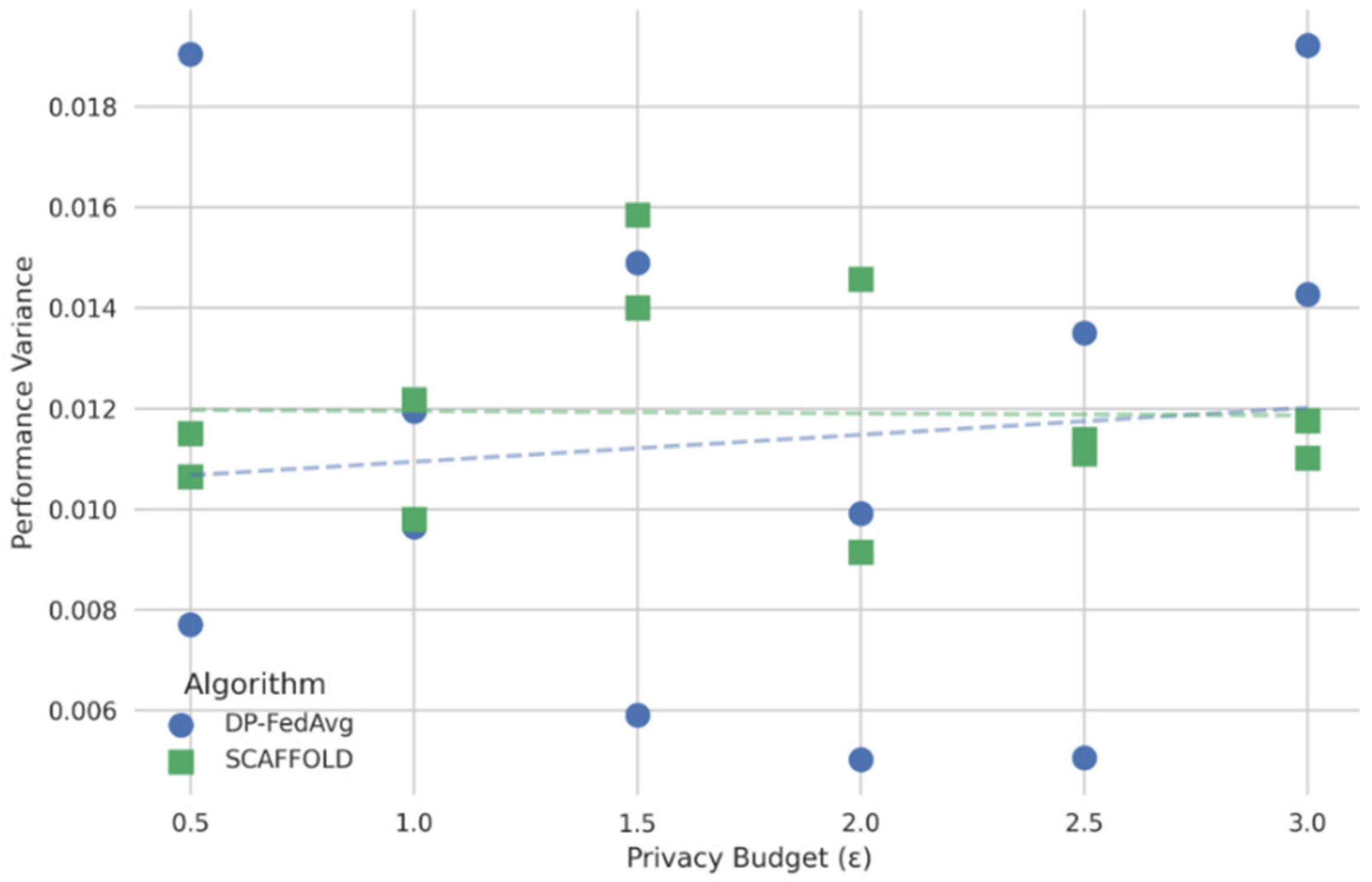

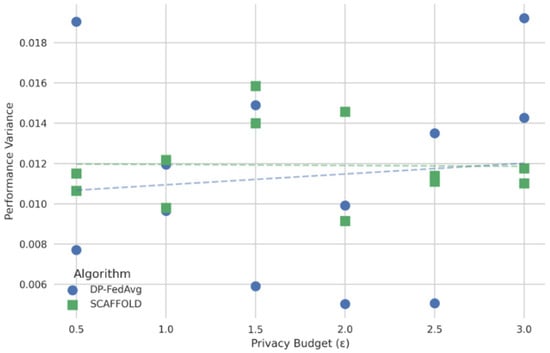

In Figure 8, the x-axis represents the privacy budgets and the y-axis performance variance. The figure’s curve illustrates a non-linear connection in which poor privacy enforcement keeps variance low (i.e., high accuracy and low F1-score variability), but variance abruptly rises above a particular level of privacy assurances. With minimal encryption, XGBoost maintained an acceptable variation among federated nodes while achieving 94.53% accuracy and an F1-score of 0.9043. As shown in the graph, as the level of privacy increases (e.g., higher noise injection or stronger encryption protocols), the model’s predictive variance also tends to increase, reflecting a decline in performance stability and generalization.

Figure 8.

Privacy budget vs. performance of different FL models.

5. Conclusions

This study discusses PHM-FL (Privacy-Preserving Health Monitoring via federated learning). It is one of the FL frameworks that allows the detection of early disease prediction using wearable sensor data. We collected the physiological signals from different sensors. The data that we collected were heart rate, resting heart rate, entropy of heart rate, normalized heart rate, calories, and activity context (lying, sitting, self-paced walking, and running at different METs). We utilized the eight machine learning models and compared both centralized and federated learning environments. Furthermore, we used four FL algorithms (FedAvg, DP-FedAvg, FedProx, SCAFFOLD) with 50 communication rounds. Our experimental observation revealed that XGBoost performed well as compared to the other models. The accuracy obtained for XGBoost was 94% in a centralized environment and also in the FL setting (0.9321 ± 0.005), with high discrimination power (ROC-AUC ≈ 0.981 ± 0.003). We also observed that the performance degradation was a ~1–2% drop in accuracy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P. and N.P.; software, N.P. and R.P.; validation, R.P.; data curation, R.P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.P. and N.P.; writing—review and editing, all authors; funding acquisition, N.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RF | Random Forest |

| GB | Gradient Boosting |

| FL | Federated Learning |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| XGB | XGBoost |

References

- Das, S.; Dutta, S.; Hazra, S.; Nandi, S.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Disha, M. Personalized Healthcare Empowered: Federated Learning Integration with Wearable Device Data for Enhanced Patient Insights. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Region 10 Symposium (TENSYMP), New Delhi, India, 27–29 September 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Aminifar, A.; Shokri, M.; Aminifar, A. Privacy-preserving edge federated learning for intelligent mobile-health systems. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 161, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, X.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, X.; Brusic, V.; Zhao, J. A privacy-preserving framework for federated learning in smart healthcare systems. Inf. Process. Manag. 2023, 60, 103167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Saha, S.; Mishra, S.; Bagade, P. A federated learning approach for smart healthcare systems. CSI Trans. ICT 2023, 11, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikumar, K.S.; Prathiba, S.B.; Alazab, M.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Pandya, S.; Khan, J.M.; Moorthy, R.S. FL-PMI: Federated learning-based person movement identification through wearable devices in smart healthcare systems. Sensors 2022, 22, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Ghosh, S.K. FEEL: FEderated LEarning Framework for ELderly Healthcare Using Edge-IoMT. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2023, 10, 1800–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Kreuter, D.; Chen, Y.; Dittmer, S.; Tull, S.; Shadbahr, T.; Preller, J.; Rudd, J.H.F.; Aston, J.A.D.; Schönlieb, C.B.; et al. Recent methodological advances in federated learning for healthcare. Patterns 2024, 5, 101006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhmetov, A.; Latif, Z.; Tyler, B.; Yazici, A. Enhancing healthcare data privacy and interoperability with federated learning. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2025, 11, e2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).