Abstract

The aim of our work was to analyze the influence of changes in humidity and temperature on temporal features of sensed photoplethysmography (PPG) waves. This paper describes a special prototype of a wearable PPG multi-sensor with an integrated I2C humidity sensor and a thermometer to carry out measurements at three skin moisture levels. This sensor is supplemented with a force-sensitive resistor for the measurement of the physical contact pressure between the measuring probe and the skin surface, which can be used to sense heart pulsation in the wrist radial artery. The experiments conducted show that the performed skin manipulation (skin drying, moistening) was always detectable; the PPG signal range is mainly affected, while changes in signal ripple and heart rate variance are smaller. The detailed analysis per hand and gender type yielded differences between male and female subjects, and the results for left and right hands differed less.

1. Introduction

For monitoring the cardiovascular system, including changes in arterial stiffness and heart rate (HR), wearable optical sensors based on the photoplethysmography (PPG) principle have been successfully applied [1,2]. The current state of the skin surface, including humidity, temperature, and other factors, can influence the precision of PPG wave parameters determined from the sensed PPG signal [3].

The aim of our work was to analyze the influence of humidity, temperature, and applied contact pressure on temporal features of sensed PPG waves. This paper describes the realization of a special prototype of a wearable PPG multi-sensor with an integrated I2C humidity sensor and a thermometer to carry out the measurement of skin condition at the position of the optical sensor. The developed sensor is supplemented with a force-sensitive resistor (FSR) element, enabling it to measure the contact pressure between the PPG sensor probe and the skin surface. The FSR component can also measure heart pulsation in the wrist radial artery and perform a comparison of HR values determined from the PPG signal [4,5]. Due to its planned use in experiments inside the scanning area of an MRI tomograph [6], the current sensor prototype consists of non-ferromagnetic materials, and all parts are shielded by aluminum boxes.

After verifying the sensor’s functionality under laboratory conditions, the stability and quality of a wireless Bluetooth (BT) connection were tested in the environment of the scanning MRI device, and the received signal strength indicator (RSSI) parameter was measured. The main measuring experiment consisted of PPG signal sensing on a wrist at different levels of skin moisture (after washing the hands, after drying the skin, etc.) before each measuring phase. The database of sensed data records collected in this way was then statistically analyzed with the final aim of giving some practical recommendations from the point of view of humidity and temperature changes during long-term experiments inside the MRI device.

2. Methods

2.1. PPG Signal Description and Feature Determination

Generally, optical PPG sensors are based on either transmittance or reflectance principles. The transmittance type of the sensor probe usually has the form of a finger ring with a light source (one or more LED elements) and a photo detector placed on opposite sides of the sensed human tissue—this realization is mainly applied in pulse oximeter devices. In the reflectance type, the photo detector measures the intensity of the light reflected from the skin, and it is placed on the same side of the skin surface as the light source. Reflectance PPG sensors are typically worn on fingers or wrists as a part of wearable devices—fitness bracelets, smart watches, etc. [7]. In both types, the picked-up PPG signal contains two local maxima, representing systolic and diastolic peaks, which provide valuable information about the pumping action of the heart [8]. The amplitude of the sensed PPG signal is usually not constant but modulated, and it can often be partially disturbed or degraded. For this reason, some de-trending and filtering must be applied to the picked-up PPG signal before its analysis [9].

To describe PPG signal properties, the energetic, temporal, and statistical parameters should be determined. First, the upper and lower envelopes (EHI, ELOW) are calculated by low-pass filtering of the squared input signal. The absolute difference between EHI and ELOW mean values (μEHI–μELOW) represents the PPG signal range (HPRANGE). Its mean, together with the maximum and minimum of the upper envelope, determines the heart pulse ripple HPRIPP = ((max EHI − min EHI)/μ HPRANGE) × 100 (in %). Then, the localized systolic peak positions PSYS are found to calculate the heart cycle periods THP (in samples). For the sampling frequency fS (in Hz), the formula HR = 60 × fS/THP determines the heart rate (in min−1). Its mean and standard deviation specify the heart rate relative variance (in %) as HRRVAR = σHR/μHR × 100.

2.2. Sensing and Analysis of Humidity and Temperature Values

Humidity sensors operate on the principle of a change in the electrical impedance (capacitance) at varying moisture levels. The sensor’s active component is typically a hygroscopic substance (a material that absorbs water or water vapor) [10] with a varying dielectric constant, which is detected and expressed as a change in relative humidity, RH (in %). Commercial non-contact air humidity and temperature sensors are usually based on monolithic chips containing an integrated I2C interface [11], so the RH values are provided in parallel with the temperature T1 ones.

To map relative humidity and temperature changes during the measurement with the time duration tDUR, the linear trend is calculated from the RH and T1 sequences (RHLT and T1LT) by the linear least squares fitting technique. Then, the differences ∆ RH and ∆ T1 between the values taken at the start and the end of the measurement phase are determined. Finally, the gradient parameters, defined as RHGRAD = (∆ RH/tDUR) [%/s] and T1GRAD = (∆ T1/tDUR) [°C/s], are successfully used for evaluation and comparison. The positive linear trends RHLT and T1LT, as well as the gradient values, represent the increasing trend; the negative ones signify the decreasing trend.

2.3. Contact Pressure Determination Using an FSR-Based Sensor

The FSR element is based on a flexible, thin-film, pressure-resistive sensor whose output resistance RFSR decreases depending on the increase in pressure applied to the sensor surface [12]. As these elements typically have a non-linear relationship between the output resistance RFSR in kΩ and the applied pressure in kg, the conductance, calculated as GFSR = 1/RFSR, is mainly used to create the pressure characteristic. In practice, the pressure measurement based on the FSR component is usually carried out by a voltage divider. It consists of a supplementary pull-down resistor R1 connected to the ground. In this case, the output signal from the voltage divider is VOUT = VADC × VCC/ADRES, where VADC represents the actual value after A/D conversion, ADRES is the resolution of the A/D converter, and VCC is the supply voltage. The final resistance of the FSR element can be enumerated as RFSR = R1 × (1 − VCC/VOUT). The depicted FSR’s conversion characteristics must be linearized before the practical use of this sensor.

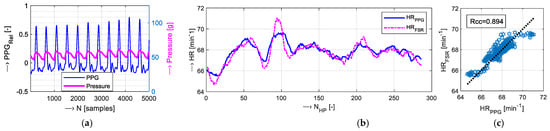

The FSR-based sensor can also be used for the detection and pickup of a blood pulsation signal in a vessel. Such a signal would be directly comparable with the PPG wave obtained by a PPG sensor that works on the optical principle. A sufficient contact pressure (CP) must be applied to the skin above the vessel to obtain well-detectable pulsation in the rhythm of the PPG wave’s systolic peaks (see an example in Figure 1a). Under these conditions, HR values (HRFSR) can be successfully calculated from the FSR signal. To evaluate the correlation between heart rates determined from the PPG signal (HRPPG) and the HRFSR sequence (see Figure 1b), the Pearson correlation coefficient Rcc and visualization in the form of a scatter plot are often used, as shown in Figure 1c.

Figure 1.

Visualization of (a) a 5 k sample PPG wave with a pressure signal measured in parallel, (b) determined HRPPG and HRFSR sequences, (c) a scatter plot with the calculated Pearson correlation coefficient Rcc.

3. Objects, Experiments, and Results

3.1. Structure and Realization of a Wearable PPG Multi-Sensor

The developed special prototype of a wearable PPG multi-sensor consists of three basic parts: the measuring probe, the sensor’s body, and the battery cell for powering. The measuring probe contains the following three components:

- A reflectance optical PPG sensor with an integrated analog interface—the Pulse Sensor Amped (Adafruit 1093) [13] by Adafruit Industries, New York, NY, USA;

- An Adafruit Si7021 Temperature & Humidity I2C Sensor (Adafruit 3251–STEMA QT) [12] by Adafruit Industries, New York, NY, USA;

- An FSR-based pressure sensor, Whadda WPSE477 [14] product, by Velleman Group NV, Gavere, Belgium.

The WPSE477 component was produced as a single-point sensor with a 7.62 mm diameter sensing area and a 0.2 mm thickness. It was constructed for a pressure range up to 0.5 kg, with a measuring accuracy of ±2.5% [14]. The Si7021 chip measures relative humidity in the range of 0–80% RH (with an accuracy of ±3%) and temperature from −10 °C to +85 °C, with an accuracy of ±0.4 °C [12].

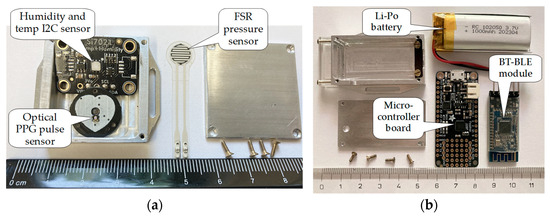

The sensor’s body part consists of an Arduino-compatible micro-controller board, Adafruit Feather 328P, by Adafruit Industries, New York, NY, USA, based on the processor ATmega328P by Atmel Corporation, San Jose, CA, USA. This processor includes eight 10-bit ADCs; it works with an 8 MHz clock frequency and uses 3.3 V logic. The Arduino board also contains integrated chips for I2C and SPI support, a hardware USART to USB converter, and a charger for lithium polymer (Li-Po) batteries [15]. For the multi-sensor wireless connection with the control device, the BT module MLT-BT05 by Techonics Ltd., Shenzhen, China, working in the BT4.0 BLE standard at 2.4 GHz [16] was used. While the whole sensor is normally powered by a 3.7 V Li-Po battery, it can also be powered by 5 V via a USB port—mainly for charging the battery cell, but also for programming the processor. The measuring probe and the sensor’s body are shielded by aluminum boxes to enable measurements in the magnetic field environment with additional radiofrequency (RF) and electromagnetic disturbance—see Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Construction of the PPG multi-sensor assembly: (a) photo of a measuring sensor part; (b) photo of a sensor’s body, including a Li-Po battery.

3.2. Auxiliary Experiments and Investigations

After verifying the sensor’s basic functionality in normal laboratory conditions, the stability of wireless communication and the quality of the BT connection between the sensor and the control laptop were tested under three operating conditions:

- The MRI device was ready to scan, but no MR sequence was running—open shielding cage door (OC1);

- Closed cage door without MR scanning (OC2);

- The MR scan sequence was executed—the door must be closed (OC3).

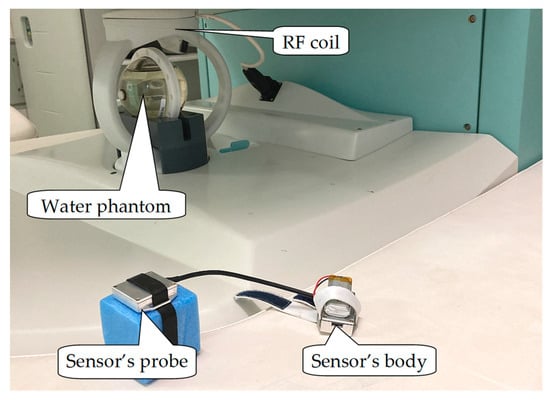

The quality of wireless communication was evaluated in the open-air MRI device E-scan Opera by Esaote S.p.A., Genoa, Italy, working with a low-static magnetic field of 0.178 T, which is located at our Institute [17]. The tested multi-sensor was present inside the scanning area of the MRI device, while the control laptop was located outside the shielding metal cage. No person was investigated for the purpose of this measurement; only a spherical water phantom (a plastic cube simulating a human wrist with the measuring probe fixed on it by a polyamide ribbon) was inserted in the RF receiving/transmitting coil—see the detail in Figure 3. The distance between the sensor and the control device was about 2.5 m, and the BT communication was operated at a rate of 57,600 bps. Within the third testing condition, the MR scan 3D-CE sequence was executed [17]. The intensity of the BT signal was evaluated by the RSSI parameter as a measure of the power level received by an RF client device from an access point [18]. The RSSI values in dBm were obtained during the BT BLE connection establishment process. The mean and std RSSI values under all three tested operating conditions (shown in Table 1) were always determined from five consecutively realized individual measurements.

Figure 3.

Arrangement of RSSI measurement inside the scanning area of the MRI tomograph.

Table 1.

Mean and std RSSI values measured under three conditions inside the E-Scan Opera device.

3.3. The Main Measurement Experiment

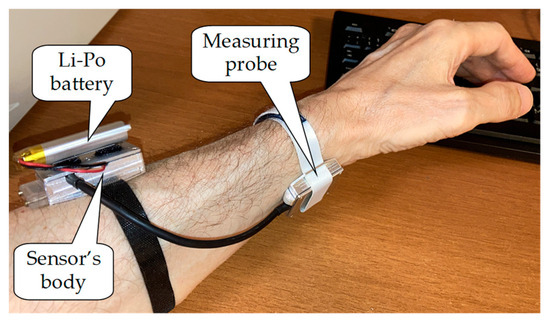

The main measurement experiment consisted of real-time sensing of PPG waves, humidity values, and temperature values, together with the information about the current contact pressure applied on the skin surface by a measuring probe. The tested person sat with a hand on a table in a normal office room. The measuring probe was placed on the wrist artery of the left or right hand, while the sensor’s body was fixed on the upper arm (see the arrangement photo in Figure 4). The measurements were realized at three skin moisture levels:

Figure 4.

Principal arrangement photo of the main measurement experiment.

- The sensor’s probe was worn without any adjustment of the skin surface of the bottom wrist area (Normal);

- The skin surface was dried by a handkerchief (Dry);

- The skin was partially moistened by a wet cloth before wearing the probe (Wet).

The real-time measurements were performed in the following phases:

- 1.

- The preparation phase M0, when the body of the PPG multi-sensor was attached to the arm of the tested person, BT connection with the control device was established, and the quality of the sensed PPG and pressure (FSR) signals was verified. Then, the skin surface was adjusted depending on the required skin moisture level.

- 2.

- The first 90 s measurement phase M1, when the RH and T1 values were taken in the intervals of TINT = 1 s. In the first 30 s of this duration, the measuring probe was freely laid on the desk (current air conditions were measured), and then the probe was put on the wrist of the tested person. At this moment, the offsets of RH and T1 sequences (RHOFS and T1OFS) were determined.

- 3.

- The main measuring phase M2, with a time duration of 256 s, when the PPG and FSR analog signals (sensed using the sampling frequency fS = 125 Hz), together with RH and T1 values (with TINT = 0.2 s intervals), were recorded in parallel.

- 4.

- The final 90 s measurement phase M3 started when the measuring probe was removed from the wrist. In this phase, RH and T1 values were again recorded using TINT =1 s.

The total time duration of the whole measurement was about 8 ÷ 10 min—depending on the length of the preparation part. The total number of detected heart periods NHP, which can be used to calculate HR values (HRPPG and HRFSR), depended on the actual state of the tested person during the measurement phase M2. The span change in the RH or T1 sequence during the measuring experiment with the sensor’s probe on the skin was calculated as a difference Y (RH or T1), ΔYPON = YM2E − YOFS, where YM2E represents the last value received from the Si7021 chip in the phase M2 (RHM2E or T1M2E) and YOFS is the offset value taken in about the 30th second of the M1 phase.

During our experiments, a small database of real-time signal records was collected. It originated from seven non-smoker right-hand dominated volunteers (four males, P1M–P4M, and three females, P1F–P3F) with a mean age of 52 ± 18 years. The collected data records consist of six files per person in total—two from the M1 and M3 phases and one from the M2 phase, picked up from the left and right hands. They were subsequently processed off-line to determine PPG and FSR signal properties and changes in RH and T1 sequences within all measuring phases M1–3.

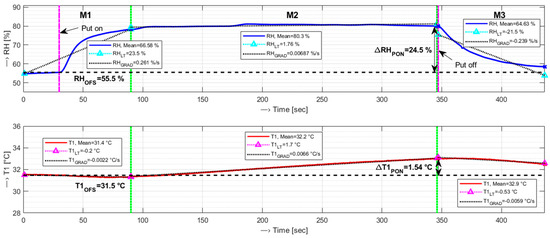

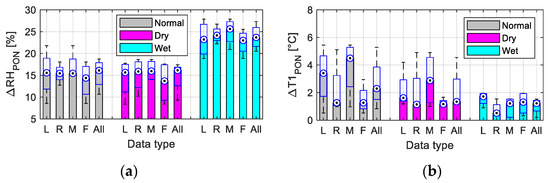

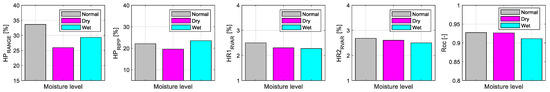

The following example describes the determination of PPG signal properties, together with parameters of RH and T1 sequences, taken from the right hand of the male testing subject P2M at the wet skin moisture level. Concatenated RH and T1 sequences for the measuring phases M1–3, with denoted time stamps indicating when the measuring probe was put on and taken off, the determined offset levels RHOFS and T1OFS, and final span changes ΔRHPON and ΔT1PON can be seen in Figure 5. Table 2 enumerates partial results for all three tested skin moisture levels. Bar graphs with box plots in Figure 6 compare differences in ΔRHPON and ΔT1PON parameters for three skin moisture levels, categorized by the used hand and the gender of the tested person separately. Figure 7 presents summary mean results for all tested subjects, visualized as bar graphs that track changes in the five most important PPG signal properties—HPRANGE, HPRIPP, HR relative variance (HR1 from HRPPG, HR2 from HRFSR values), and Rcc.

Figure 5.

Concatenated RH (upper graph) and T1 (lower graph) sequences for the measuring phases M1–3 taken at the wet skin moisture level, with denoted time stamps indicating when the measuring probe was put on and taken off, determined offset levels, and final span changes; right hand of the subject P2M.

Table 2.

Partial results of PPG signal properties and HR statistical features for three skin moisture levels; right hand of the subject P2M, applied contact pressure CP ≅ 100 g.

Figure 6.

Basic statistical properties compared by the used hand (left/right) and the gender of the tested subject (male/female), and summary properties (All) for three skin moisture levels: (a) ΔRHPON; (b) ΔT1PON parameters.

Figure 7.

Bar graphs of summary mean results for both hands and all tested subjects (from left to right): values of HPRANGE, HPRIPP, HR relative variance (HR1 from HRPPG, HR2 from HRFSR), and RCC.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The performed measurement confirms the functionality of the developed special prototype of a wearable multi-sensor that enables the measurement of PPG signals, relative humidity, temperature values, and contact pressure by an FSR element. Auxiliary experiments were used to check the practical possibility of wireless BT connection and data transfer through the shielding cage of the open-air MRI device. The minimum RSSI of −94 dBm was reached when the cage door was closed and the MR scan sequence was running, but the BT connection was stable, the real-time data transfer was still functional, and the data received from analog signals could be used for further processing and analysis.

Principally, differences exist between the skin properties of male and female subjects. Female skin has generally slightly thinner capillaries, so a lower contact pressure must be applied to obtain a proper signal from the FSR sensor—suitable for HR value detection and comparison with values obtained from the PPG signal. Therefore, we finally tried to apply the mean contact pressure of μ CP = 100 g for the male subjects and μ CP = 75 g for the female subjects.

As confirmed by visualization of the concatenated RH and T1 sequences for the measuring phases M1 and M3, the 90 s time duration was chosen properly—during the main measuring phase M2, the changes in RH were minimal (see the upper graph in Figure 5). In the case of temperature skin changes, which are affected for a longer time, a small increase in T1 values could be observed within the M2 phase. The proposed return of T1 values to the offset level during the M3 phase was not practically fulfilled, as shown in the lower graph in Figure 5. For this reason, about a one-minute time delay was finally applied before the next measurement at different skin moisture levels to minimize this undesirable effect.

The obtained results of the realized main measuring experiments show that the performed skin manipulation (skin drying and/or moistening) was well detectable—see the changes in the ΔRHPON parameter in Figure 6. As can be seen, when moistening was applied, the highest ΔRHPON values were achieved. From the point of view of ΔT1PON parameters, the situation was the opposite—moistening produced the smallest values. The detailed analysis performed separately for each hand and gender indicates that differences existed in ΔRHPON values between the results of the male and female subjects, but the results of measurements from the left and right hands differed less (not significantly). In the case of the ΔT1PON parameter, the obtained values differed significantly for each gender as well as each hand. These conclusions must be confirmed by further experiments—at present, a small number of measurements on subjects were realized (four males and three females only).

From the point of view of PPG signal properties, different skin moisture levels are mainly expressed by changes in the HPRANGE and HPRIPP parameters (see the first two graphs in Figure 7). Skin manipulation does not have a direct influence on the variance in the calculated HR values (obtained mean HR variance values are comparable/similar), but in all cases, the HRs determined from the FSR signal have higher HR2RVAR. The smallest Rcc values (HRPPG and HRFSR differing mostly) were obtained after the skin moistening operation, as documented by the right bar graph in Figure 7. So far, we cannot find any explanation for this effect; more measuring experiments planned in the near future could also cover this phenomenon.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, J.P. and A.P.; data collection and processing, J.P. and T.D.; HW realization and testing, J.P. and T.D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P. and A.P.; writing—review and editing, A.P.; project administration, J.P.; funding acquisition, J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Slovak Scientific Grant Agency project VEGA2/0004/23.

Institutional Review Board Statement

An institutional review board statement was waived for this study because the authors tested themselves and colleagues from IMS SAS. No personal data were saved; only PPG signals, contact pressure force values, and skin humidity and temperatures sensed on left/right wrists were used in this research.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dieffenderfer, J.; Goodell, H.; Mills, S.; McKnight, M.; Yao, S.; Lin, F.; Beppler, E.; Bent, B.; Lee, B.; Misra, V.; et al. Low-Power Wearable Systems for Continuous Monitoring of Environment and Health for Chronic Respiratory Disease. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2016, 20, 1251–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlton, P.H.; Marozas, V. Wearable photoplethysmography devices. In Photoplethysmography: Technology, Signal Analysis, and Applications; Kyriacou, P.A., Allen, J., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2022; pp. 401–438. [Google Scholar]

- Kazanskiy, N.L.; Butt, M.A.; Khonina, S.N. Recent Advances in Wearable Optical Sensor Automation Powered by Battery versus Skin-like Battery-Free Devices for Personal Healthcare—A Review. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Acquisto, L.; Scardulla, F.; Montinaro, N.; Pasta, S.; Zangla, D.; Bellavia, D. A preliminary investigation of the effect of contact pressure on the accuracy of heart rate monitoring by wearable PPG wrist band. In II Workshop on Metrology for Industry 4.0 and IoT; MetroInd4.0&IoT: Naples, Italy, 2019; pp. 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardulla, F.; D’Acquisto, L.; Colombarini, R.; Hu, S.; Pasta, S.; Bellavia, D. A Study on the Effect of Contact Pressure during Physical Activity on Photoplethysmographic Heart Rate Measurements. Sensors 2020, 20, 5052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Přibil, J.; Přibilová, A.; Frollo, I. First-step PPG signal analysis for evaluation of stress induced during scanning in the open-air MRI device. Sensors 2020, 20, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scardulla, F.; Cosoli, G.; Spinsante, S.; Poli, A.; Iadarola, G.; Pernice, R.; Busacca, A.; Pasta, S.; Scalise, L.; D’Acquisto, L. Photoplethysmograhic sensors, potential and limitations: Is it time for regulation? A comprehensive review. Measurement 2023, 218, 113150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzan, M.; Ovadia-Blechman, Z. Physical and physiological interpretations of the PPG signal. In Photoplethysmography: Technology, Signal Analysis, and Applications; Kyriacou, P.A., Allen, J., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2022; pp. 319–339. ISBN 978-0-12-823374-0. [Google Scholar]

- Elgendi, M. PPG Signal Analysis: An Introduction Using MATLAB; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 27–36. ISBN 978-1-138-04971-0. [Google Scholar]

- Humidity Sensor–Types and Working Principle. 7 June, 2024 By Bala, © 2024 Electronicshub.org. Available online: https://www.electronicshub.org/humidity-sensor-types-working-principle/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Si7021-A20 Data Sheet-I2C Humidity and Temperature Sensor, Rev. 1.3 6/22. © 2022 by Silicon Laboratories. Available online: https://www.silabs.com/documents/public/data-sheets/Si7021-A20.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- FSR Integration Guide & Evaluation Parts Catalog with Suggested Electrical Interfaces, Version 1.0, 90-45632 Rev. D, 24 p., Interlink Electronics Inc.: Camarillo, CA, USA. Available online: https://www.sparkfun.com/datasheets/Sensors/Pressure/fsrguide.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Pulse Sensor Amped Product (Adafruit 1093): World Famous Electronics llc. Ecommerce Getting Starter Guide. Available online: https://pulsesensor.com/pages/code-and-guide (accessed on 16 July 2020).

- FSR Sensor Module Whadda WPSE477–Manual Velleman. Available online: https://cdn.velleman.eu/downloads/25/prototyping/manual_wpse477.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Adafruit Feather 328P by Ada, Last Edited 23 August, 2024. Available online: https://cdn-learn.adafruit.com/downloads/pdf/adafruit-feather-328p-atmega328-atmega328p.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- MLT-BT05 4.0 Bluetooth Serial Communication Module. Available online: https://www.techonicsltd.com/product/mlt-bt05-ble4-0/ (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- E-Scan Opera. Image Quality and Sequences Manual; Revision 830023522; Esaote S.p.A.: Genoa, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- RSSI-Received Signal Strength Indication. Available online: https://www.rfwireless-world.com/Terminology/RSSI-Received-Signal-Strength-Indication.html (accessed on 3 February 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).