Abstract

A hysterectomy is a common surgery performed to remove a woman’s womb (uterus). Monitoring health after a hysterectomy is also extremely important, especially if the ovaries are still present. At that point, the functioning of the ovaries and their impact on a woman’s metabolism or cardiovascular health are still in question, which is why we proposed this study. The combination of wearable sensors and Artificial Intelligence helps with post-hysterectomy health monitoring, especially for women who retain their ovaries. Ovarian function remains vital for hormone balance, cardiovascular health, and metabolic regularity. As traditional approaches lose effectiveness over time, this novel approach explores data collection and AI-driven analytics to address these challenges.

1. Introduction

A hysterectomy is the surgical removal of the uterus, a pear-shaped organ which plays a crucial role in menstruation, fertility, and nourishing a developing baby during pregnancy. A hysterectomy can be performed in many ways: through varying counts of surgical cuts in the belly, a single cut in the belly called an open/abdominal hysterectomy, or three to four small surgical cuts followed by the use of a laparoscope in order to perform a robotic surgery. It can also be performed through surgical cuts in the vagina, optionally using a laparoscope (called a vaginal hysterectomy) [1]. There may be many reasons why a woman may require a hysterectomy, with some common reasons being cancer of the uterus, endometrial cancer (in most cases), cancer of the cervix, cervical dysplasia that leads to cancer, cancer of the ovary, etc. It is also performed at times as a measure for adenomyosis or other severe long-term vaginal bleeding which is not controlled by other treatments, uterine prolapse, uterine fibroid, severe endometriosis, severe infections involving the uterus, etc. All parts of the uterus can be removed during a hysterectomy, including the Fallopian tubes and the ovaries [2].

There are some common side effects of a hysterectomy like vaginal bleeding and drainage (lasts up to six weeks), difficulties during excretion, soreness/irritation at the area of incision, fatigue, and tiredness. It is a major surgery with a long recovery, presenting with various side effects depending on the type of surgery the patient undergoes. Though bleeding and infections remain a risk, many premenopausal patients do not prefer a hysterectomy due to the decreased ovarian function after the surgery is performed. There are indications of various menopausal symptoms across patients who have undergone hysterectomy. Even though ovarian preservation is increasingly common, studies have proven that ovarian function fails 4 years earlier than the natural menopause after the surgery. Studies have shown contradictory and conflicting results about the effect of a hysterectomy on ovarian function [3,4]. Certain studies reported that hormonal levels were not influenced after a hysterectomy: no change was detected in the FSH, E2, and other hormonal levels evaluated at the 3 months and 1 year time points. Another conflicting study shows that the surgery interrupts the ovarian branch of the uterine artery and reduces the ovarian blood supply by 50–70%, resulting in decreased ovarian function. Ovarian function can be assessed through its ability to produce eggs and hormones. This is achieved through biochemical hormone tests, ultrasound imagery, and other monitoring methods like Basal Body Temperature, cervical mucus monitoring, blood, urine, and salivary tests, etc. [5]. Despite these methodologies to assess ovarian functionality after a hysterectomy, there are several limitations to the technologies available to classify ovaries after the surgery, hence leading to this research. This study demonstrates the use of the CNN (Convolutional Neural Network) and LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) algorithms and a combination of the two as a DFG-Net Hybrid model.

There are wearable devices which are used to track fertility cycles and can be worn on the wrists, fingers, intravaginally, and inside the ear. There have been some notable advancements like the Oura Ring, manufactured by Oura Health Ltd. in Oulu, Finland, which is used to track menstruation through tracking changes in sleep cycle, temperature, and heart rate, and the Ava Ring, which is used to track fertility [6]. As such, these devices are becoming an important assistant to analyze certain physiological parameters which can help monitor and track reproductive health [7]. This shows the need to evaluate and review the wearable technologies which are used to detect changes, monitor, and understand a woman’s reproductive well-being. This study unfortunately does not use data directly from these sources due to the strict privacy regulations surrounding gynecological data. This study employed high-fidelity synthetic datasets and replicated clinical patterns of ovarian function, enabling development in AI models.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study Outline

This research involves the use of CNN and LSTM algorithms to create a fusion DFG- Net Hybrid model which is used to detect and classify ultrasound scans and hormonal data into 5 classes divided on the basis of ovarian functionality. The model takes several factors into consideration for both ultrasound transvaginal scans and other important variables like heart rate (HR), skin temperature, GSR, respiration rate, etc., which will be justified further into the study to classify the provided data to a class. It has been trained on synthetically generated data which replicates realistic available data, which shows the scope and potential of this particular AI approach to tackle the lack of technology to monitor reproductive health.

2.2. Description of Wearable Sensor Types

Wearable patches and other smart wearables like rings and bracelets are some commonly used wearables used to monitor and track reproductive health to obtain important hormonal data. Though blood, urine, and saliva tests, the derived samples are widely used to measure important hormones like FSH, LH, progesterone, AMH, prolactin, and thyroid hormones. There can be inconveniences caused by regular visits to the clinic, the discomfort caused, and a lack of accuracy at times which calls for innovation and technology to be used in the field, allowing at-home checkups and personalized and accurate insights. The sex hormone “estrogen” plays an important role in understanding a woman’s health and fertility. High levels of estrogen are more than just disclaimers of breast and ovarian cancer but can also be an important indicator of ovarian functioning. Estradiol is the most potent form present in the estrogen class of hormones which is necessary for the regulation and development of secondary sexual characteristics and the reproductive cycle [7]. This is collected using blood or urine samples and is checked for and monitored in clinics and laboratory environments. Recent developments have enabled scientists to detect the presence of estradiol in sweat and researchers say it will be possible and easier to monitor estradiol levels at home. This is the logic used by Caltech’s Wearable Estrogen Sweat Sensor, using a wearable aptamer nano biosensor which is integrated into a skin-worn patch. Other skin-interfaced technologies include the use of a gold nanoparticle “MXene”-based detection electrode with a low limit of detection. Wearables like watches, rings, shirts, and straps which monitor heart rate, ECG, heart rate variability (HRV), oxygen saturation (SpO2), respiration, and skin temperature are also visible in this industry [8].

2.3. Data Acquisition for Research and Study

The data used for this study as mentioned earlier is synthetically generated and it does not represent real patient information. This data is exclusively used for research and demonstration purposes in order to illustrate the potential of Artificial Intelligence techniques to assess ovarian function. By generating synthetic data, AI-driven approaches can be explored and validated in a controlled environment, showing how these methods can be applied in future clinical settings to monitor ovarian health accurately.

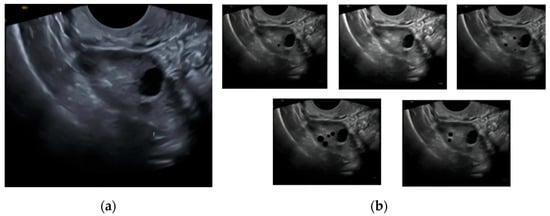

The CNN model uses ultrasound transvaginal scans for around 250 synthetically generated cases under 5 classes divided on the basis of ovarian function (Figure 1). The classes are active, inactive, declining, perimenopausal, and anomalous [9]. There are around 50 cases for each case in order to simulate realistic transvaginal ultrasound scans and make sure that the model learns most visual features of the various ovarian functionality classes.

Figure 1.

Demonstration of synthetic dataset creation: (a) base transvaginal image used for synthesis; (b) derived class images (active, inactive, declining, perimenopausal, and anomalous).

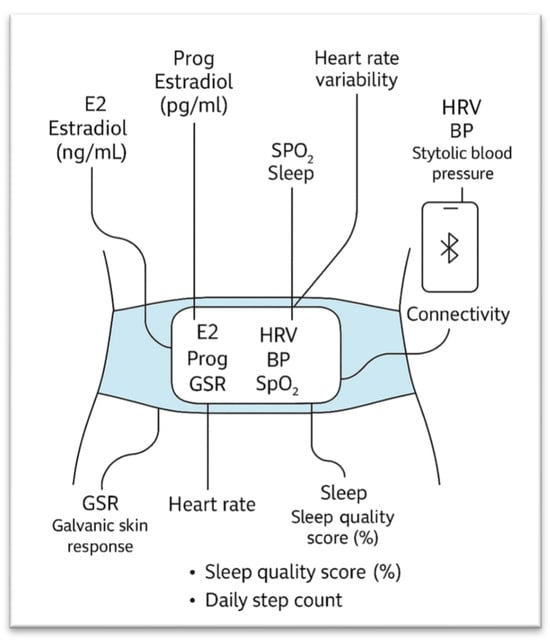

The LSTM model uses some important hormonal variables which are crucial when it comes to determining ovarian function. The data generated was tracked for 30 days per case for around 50 cases per class. The LSTM model which was combined with the above CNN model uses a synthetically generated dataset with the following variables (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Wearable sensors measuring physiological and hormonal variables used for this study.

E2 = Estradiol (pg/mL), Prog = Progesterone (ng/mL), GSR = Galvanic Skin Response, BBT = Basal Body Temperature, HR = Heart Rate, HRV = Heart Rate Variability, BP = Systolic Blood Pressure, SpO2 = Blood Oxygen Saturation, Sleep = Sleep Quality Score (%), and Steps = Daily Step Count. The above variables are crucial for understanding and dividing the ovary’s function into 1 of the 5 classes [6,7,8]. The classes and logic used for this LSTM model are the same as the CNN model above which will allow the creation of the DFG-Net Hybrid model, which incorporates both visual ultrasound transvaginal scans and the above listed hormonal data to classify cases.

2.4. Model Architecture

A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is a deep learning model which is specifically good at image-related tasks. It consists of layers which learn the features provided to it for processing. Early layers learn simple features like edges in the image; middle layers study the textures and parts; while the deeper layers learn object-level features. Convolutional layers contain filters and kernels which slide over the image to detect specific features. Pooling layers are used to reduce the spatial size, keeping only important information, and finally fully connected layers are used to classify images on the basis of learned features.

The architecture of the CNN used for this study starts with an input layer that takes grayscale images of size 256 by 256 pixels with a single channel. It then applies the input to three convolutional layers with larger filter sizes of 32, 64, and 128, each with a 3 × 3 kernel to learn and extract features like edges, textures, and shapes. Following each of the convolutional layers is a max pooling layer that halves the spatial dimensions, which is used to retain the most important features while decreasing the computational requirements. The output of the last pooling layer is flattened into a one-dimensional vector of length 115,200 to set it up for the fully connected layers. A dense layer of 128 neurons, which is named the “feature_layer,” is then obtained from this flattened vector to extract higher-level features. A dropout layer with a rate of 40% is then utilized to prevent overfitting by randomly deactivating certain neurons during training. Lastly, the output layer is a dense layer of 5 neurons, which is the number of classes, and uses the softmax activation function to produce probabilities for classification [9,10,11].

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) is a type of recurrent neural network (RNN) architecture that is well suited to sequential data and time series. Unlike vanilla neural networks, LSTMs consist of memory cells with the capacity to retain information from long sequences to learn temporal dependencies and patterns in data that arise over time. They possess gates that control information flow, selecting what to forget, update, or remember, and this allows them to circumvent the vanishing gradient problem associated with vanilla RNNs. Dropout layers may be added between LSTM layers to prevent overfitting by randomly disabling some of the units during training. Fully connected (dense) layers subsequently decode the sequence’s learned features to perform tasks like classification or regression.

The model starts with an LSTM layer of 64 units that consumes sequences of 260 timesteps and outputs a sequence of the same length but of reduced feature dimension. The following is a dropout layer to avoid overfitting. The second LSTM layer consists of 32 units and outputs only the final output vector, retaining the sequential information. The following dropout layer is used. Next comes a dense layer of 32 neurons to further transform the output before the final dense layer of 5 neurons gives out the classification output, which is 5 target classes [12,13,14].

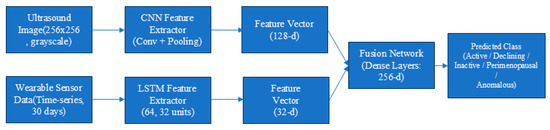

The suggested fusion classifier is a feedforward sequential neural network taking a fixed-size feature vector as input, a feature fusion from the previous CNN and LSTM models. The architecture includes three dense layers of decreasing neuron sizes 256, 128, and 64, each but the last is followed by dropout layers with a dropout of 30% to regularize the model. The last dense layer is made up of neurons equal to the number of classes and has a softmax activation to produce classification probabilities [15,16,17].

The features learned by the CNN model (learning fine-grained spatial patterns of an image) and the LSTM model (learning temporal or sequential patterns) are fused into one fused feature vector in an “.npy file”. The fused vector utilizes complementary information: the CNN learns spatial image-level fine-grained features and the LSTM temporal or sequential patterns. The fusion model learns to classify the fused features more accurately than the individual models.

2.5. Tools and Software Used

This study intensively used libraries like TensorFlow 2.20.0 to implement the models and perform encoding, decoding, and feature extraction. NumPy 2.3.x was used to generate and synthetically produce hormonal data for the LSTM model. The library OpenCV (via the opencv-python package) was used to generate the synthetic ultrasound data required by the CNN model. Matplotlib 3.10.x was employed to apply and visualize augmentations to further strengthen the model.

3. Results and Inferences

Acknowledging the synthetic nature of the data used for this study, the accuracy scores of the following models would not be an appropriate indicator of their utility, as the datasets have been generated in such a way that the models learn most of the features accurately in order to correctly classify the input to the specified functioning class. The use of synthetic data that was algorithmically generated based on known physiological ranges and annotated imaging results in the model achieving a near-perfect classification accuracy. However, these results should not be interpreted as a clinical validation, but rather as a demonstration of the feasibility and structure of the proposed fusion model (DFG-Net). The performance may vary when applied to real-world patient data with inter-individual variability and noise but can be adjusted accordingly to provided data.

3.1. CNN and LSTM Performance

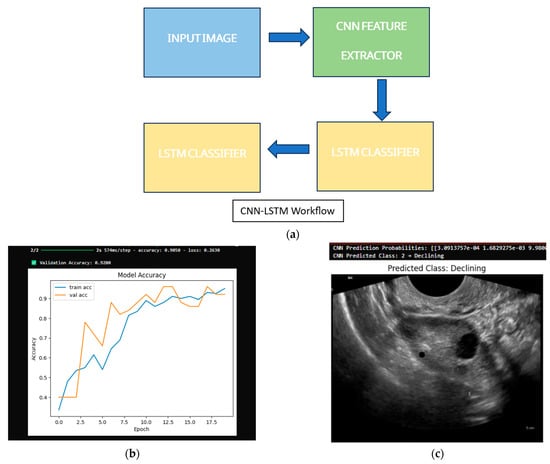

The CNN model was provided with a test image that was under the class “declining” to test its predictions. The model successfully classified images, as shown in Table 1, and its training was completed on the synthetically generated data. Output: (CNN Prediction Probabilities: [3.0913757 × 10−4, 1.6829275 × 10−3, 9.9800020 × 10−1, 7.5929743 × 10−6, 6.6543578 × 10−8] (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Indicators of ovarian function used to create classes [9].

Figure 3.

CNN and LSTM model performance: (a) CNN input and prediction; (b) model accuracy with validation score; (c) output classification.

CNN Predicted Class: 2 → Declining.

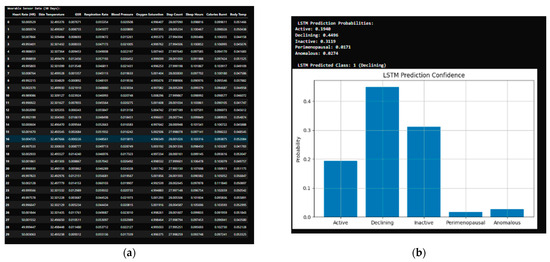

The LSTM model was provided a sample case for 30 days under the class “declining”, which it predicted accurately. Output: LSTM Prediction Probabilities: (Active: 0.1178, Declining: 0.5426, Inactive: 0.0939, Perimenopausal: 0.0730, Anomalous: 0.1727; LSTM Predicted Class: (Declining)) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

LSTM model evaluation: (a) dataset sample provided; (b) predictions of LSTM model.

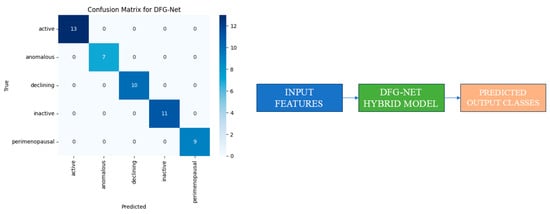

3.2. DFG-Net Hybrid Model Performance

This was the performance of the DFG-Net Hybrid model after using the feature extracted layers from both the CNN and LSTM networks. The model was tested on the samples provided individually to the models above to obtain the following output (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 5.

DFG-Net Hybrid model performance.

Figure 6.

Architecture of the proposed DFG-Net hybrid fusion model combining CNN-based ultrasound features and LSTM-based time-series features for ovarian state classification.

The fusion classifier, using both inputs taken by the LSTM and CNN, was used to classify the case into one class, “declining”, which was predicted accurately.

4. Discussion

The results of this study point toward a promising approach in how ovarian health may be monitored following a hysterectomy for women who retain their ovaries. The Hybrid model—DFG-Net—was able to classify ovarian function with a remarkably high accuracy. Although the data used for this research was synthetically generated, the consistent results across both the CNN and LSTM models provide useful insight into the potential of such a system in real-life applications when provided with the appropriate data.

One of the main takeaways is how effectively the fusion model combines two very different types of inputs: visual and physiological. The CNN handled the imaging component, focusing on ovarian structure and follicle patterns from the ultrasound scans, while the LSTM tracked physiological changes over time, such as hormonal levels and other important signs. This multimodal approach is especially valuable in cases where one modality (like ultrasound) becomes less reliable as ovarian visibility fades over the years.

4.1. Comparison to Standard Procedures

Traditionally, gynecological follow-up after hysterectomy is based on occasional imaging and blood tests, sometimes only when symptoms are present. These methods are periodic, sometimes invasive, and not always sensitive to subtle or gradual changes. In contrast, wearable technologies provide round-the-clock, passive data collection with minimal disruption to daily life. Coupled with AI, this stream of information can be processed to spot trends or anomalies that might otherwise go unnoticed until much later.

4.2. Limitations and Considerations

Despite these encouraging outcomes, there are several limitations worth noting. First and foremost, the model was tested on data that was artificially generated based on known physiological patterns and ranges. While this is useful for building a proof-of-concept, it does not account for the variability seen in real-world patient data until it is trained and evaluated. Additionally, the technology required to collect and analyze this type of data—especially multi-sensor devices—may not be affordable or available in all settings.

In conclusion, this makes it crucial to validate the approach with clinical trials and data collected from actual users over longer periods of time.

5. Conclusions

This research presents the development, progress, and status of wearable technology available and created to assess ovarian function after a hysterectomy. Artificial Intelligence was also showcased as a potential technological approach. The DFG-Net fusion model, which brings together time series sensor inputs and ultrasound-based imaging, has shown a strong performance across the ovarian function classes. Beyond accuracy, its real strength lies in its potential to provide consistent and diverse conclusions on a woman’s ovarian health after using a multimodal approach which considers both visual and physiological factors.

As gynecology moves toward more individualized and preventive care models, technologies like this may offer a valuable addition to standard follow-up protocols. It reduces the gap between traditional diagnostics and upcoming digital health tools, potentially reshaping how clinicians approach long-term monitoring. What comes next? The priority should be to collect more diverse data—including real-world sensor recordings and clinical images—to validate and fine-tune the approach. Clinical trials would help measure not just accuracy but also the model’s impact on treatment outcomes. Additionally, cost-effectiveness studies would be necessary to determine how and where such a system could be realistically implemented. With these steps, this technology could move beyond research and into everyday care, offering women a more informed and responsive healthcare experience post hysterectomy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.R. and A.P.C.; methodology, A.P.C.; software, A.P.C.; validation, G.R. and A.P.C.; formal analysis, A.P.C.; investigation, G.R.; resources, G.R.; data curation, G.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.C.; writing—review and editing, G.R.; visualization, A.P.C.; supervision, G.R.; project administration, A.P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is not publicly available as it was synthetically generated just for the purpose of this research.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the open-source tools and datasets that enabled the development of the synthetic data and models for the research methodology, TensorFlow, OpenCV, NumPy, and Matplotlib, and are also grateful to the organizers of the 12th International Electronic Conference on Sensors and Applications for accepting the abstract and for encouraging the continuation of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cleveland Clinic. Hysterectomy—Description. Available online: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/procedures/hysterectomy (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Abdelazim, I.A.; Abdelrazak, K.M.; Elbiaa, A.A.M.; Farghali, M.M.; Essam, A.; Zhurabekova, G. Ovarian function and ovarian blood supply following premenopausal abdominal hysterectomy. Prz. Menopauzalny 2015, 14, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gökgözoğlu, L.; İslimye, M.; Topçu, H.O.; Özcan, U. The effects of total abdominal hysterectomy on ovarian function—Serial changes in serum anti-Müllerian hormone, FSH and estradiol levels. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 23, 821–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farquhar, C.M.; Sadler, L.; Harvey, S.A.; Stewart, A.W. The association of hysterectomy and menopause: A prospective cohort study. BJOG 2005, 112, 956–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalmers, C. Does hysterectomy in a premenopausal woman affect ovarian function? Med. Hypotheses 1996, 46, 573–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, C.; Wang, M.; Min, J.; Tay, R.Y.; Lukas, H.; Sempionatto, J.R.; Li, J.; Xu, C.; Gao, W. A wearable aptamer nanobiosensor for non-invasive female hormone monitoring. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2024, 19, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyzwinski, L.; Elgendi, M.; Menon, C. Innovative approaches to menstruation and fertility tracking using wearable reproductive health technology: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e45139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negaral, I.M.O. The role of wearable technology in enhancing patient monitoring and preventive sexual and reproductive health care. Glob. Int. J. Innov. Res. 2024, 2, 2331–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borna, M.R.; Saadat, H.; Sepehri, M.M.; Torkashvand, H.; Torkashvand, L.; Pilehvari, S. AI-powered diagnosis of ovarian conditions: Insights from a newly available dataset of ultrasound images. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1520898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, P.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, K. Ultrasound image-based convolutional neural networks to differentiate tubal ovarian abscess and ovarian endometriosis cyst: A retrospective cohort. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1101810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman Hosain, A.K.M.; Mehedi, M.H.K.; Kabir, I.E. PCONet: A convolutional neural network architecture to detect polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) from ovarian ultrasound images. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.00407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostayed, A.; Luo, J.; Shu, X.; Wee, W. Classification of 12-lead ECG signals with Bi-directional LSTM network. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.02090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.D. Time–frequency time–space LSTM for robust classification of physiological signals. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostami, A.; Motaman, K.; Tarvirdizadeh, B.; Alipour, K.; Ghamari, M. LSTM-based real-time stress detection using PPG signals on raspberry Pi. IET Wirel. Sens. Syst. 2024, 14, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Kim, T.; Han, M.-R.; Kim, S.; Kim, G.; Lee, S.; Choi, Y.J. Ovarian tumor diagnosis using deep convolutional neural networks and a denoising convolutional autoencoder. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikramaratne, S.D.; Mahmud, S.M. A ternary Bi-directional LSTM classification for brain activation pattern recognition using fNIRS. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.05892v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, Z.C.; Kale, D.C.; Elkan, C.; Wetzel, R. Learning to diagnose with LSTM recurrent neural networks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.03677. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).