Abstract

In the last few decades, several wearable devices have been designed to monitor respiration rate to capture pulmonary signals with a higher accuracy and reduce patients’ discomfort during use. In this article, we present the design and implementation of a device for the real-time monitoring of respiratory system movements. When breathing, the circumference of the abdomen and thorax changes; therefore, we used a Force-Sensing Resistor (FSR) attached to a Printed Circuit Board (PCB) to measure this variation as the patient inhales and exhales. The mechanical strain this causes changes the FSR electrical resistance accordingly. Also, for streaming this variable resistance on an Internet of Things (IoT) platform, Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) 5 is utilized due to its adequate throughput, high accessibility, and the possibility of power consumption reduction. In addition to the sensing mechanism, the device includes a compact, energy-efficient micro-controller and a three-axis accelerometer that captures body movement. Power is supplied by a rechargeable Lithium-ion Polymer (LiPo) battery, and energy usage is optimized using a buck converter. For comfort and usability, the enclosure was 3D printed using Stereolithography (SLA) technology to ensure a smooth, ergonomic shape. This setup allows the device to operate reliably over long periods without disturbing the user. Altogether, the design supports continuous respiratory tracking in both clinical and home settings, offering a practical, low-power, and portable solution.

1. Introduction

Respiratory rate frequency provides additional levels of information about the physical and mental condition of a person. Therefore, the accurate monitoring of the respiratory system allows for a more precise diagnosis for people with certain medical conditions [1,2]. Abnormalities in the respiratory cycle are closely linked to various respiratory diseases, emphasizing the importance of understanding its dynamics [3]. The respiratory cycle consists of two main phases: inspiration and expiration. During inspiration, the lungs expand to draw in environmental air, while expiration involves the relaxation of the lungs to release a gas mixture, primarily composed of carbon dioxide [4,5]. Regarding the prediction of physical problems, we can mention the application of respiration monitoring sensors in recognizing signs of respiratory depression in patients recovering from surgery and anesthesia, detecting sleep-related breathing disorders, and, most recently, for managing patients with COVID-19 to constantly track pulmonary function [6,7]. More to the point, respiration rate can also be associated with the emotional state of a person, for instance, sadness, depression, happiness, anxiety, etc. [8]. Considering the vital role of the proper functioning of the respiratory system, keeping track of a patient’s breathing rate noninvasively has always been an issue of interest. Also, the design of these sensors must minimize the impact on the patient’s daily life and provide comfort during use [9]. A variety of research has been conducted on developing respiratory monitoring sensors. To name but a few, bed-type sleep monitoring systems have been proposed, which can be used only during sleep. Furthermore, some non-contact wearable sensors have recently been developed, which may also cause discomfort for patients due to the additional belts attached [10]. In this work, we designed a handy, easy-to-use Printed Circuit Board (PCB) containing a Force-Sensitive Resistor (FSR) to measure pressure and an accelerometer that ultimately senses the respiration signal of a patient. We can measure force by measuring the changes in FSR resistance. It is also possible to detect the motion of the body with the help of a three-axis accelerometer [11]. Further benefits of incorporating FSR and accelerometer include accuracy, cost-effectiveness, and thinness [12]. Altogether, we have developed a wearable device for capturing respiratory signals with a convenient and unobstructed design for patient use. In addition, we have offered other features, including a high precision and power consumption of 4.9 mW.

2. Methods

2.1. Hardware Overview

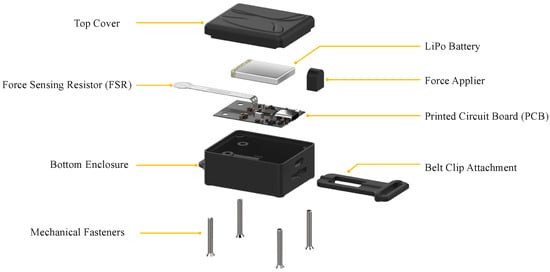

The goal of this research is to design a device that can measure respiration rate through the measurement of chest movements. The components of this device had been selected according to their low power consumption, functionality, and high relative accuracy. An overview of the proposed device’s physical structure and internal components is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Exploded view of the proposed wearable respiratory monitoring device.

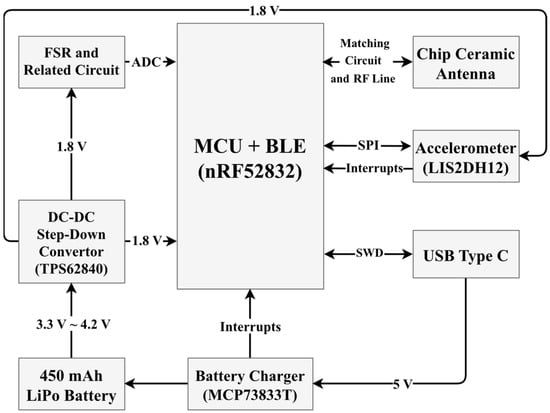

As depicted in the hardware diagram (Figure 2) and the assembled PCB layout (Figure 3), an ARM Cortex M4F processor and various peripherals, such as Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) 5, are deployed [13]. Additionally, there is a USB type-C jack that is connected to the battery charger (MCP73833T) to charge a 450 mAh Lithium Polymer (LiPo) battery [14]. LiPo batteries can meet the needs of medical device applications due to their remarkable features like good cycle life, rechargeability, light weight, and high energy density [15]. It has an accelerometer (LIS2DH12) for detecting user motion [11]. A high-efficiency miniature DC-DC switching buck converter must be used to supply 1.8 V from the LiPo battery to the FSR, Micro-Controller Unit (MCU), and related circuits. TPS62840 is an excellent choice for this goal. It also has enough load capability [16].

Figure 2.

Block diagram of the device. The common supply voltage for most of the components is 1.8 V. However, the Step-Down Converter is directly powered by a 450 mAh LiPo battery.

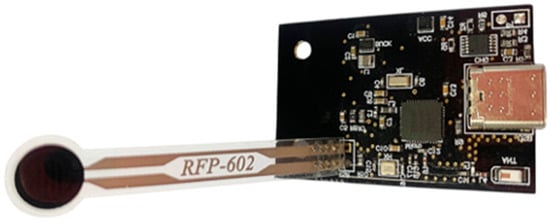

Figure 3.

PCB of the respiration device.

2.2. Micro-Controller Unit (MCU)

We used nRF52832 as the MCU. It has a low-power 32-bit ARM Cortex M4F processor. Also, BLE 5, which has enough throughput and a low power consumption, exists in nRf52832 as a peripheral. The processor has other peripherals, as well as General Purpose Input/Outputs (GPIOs) and an Analog to Digital Converter (ADC). Both battery percentage and FSR are measured using ADC.

2.3. Force-Sensitive Resistor (FSR)

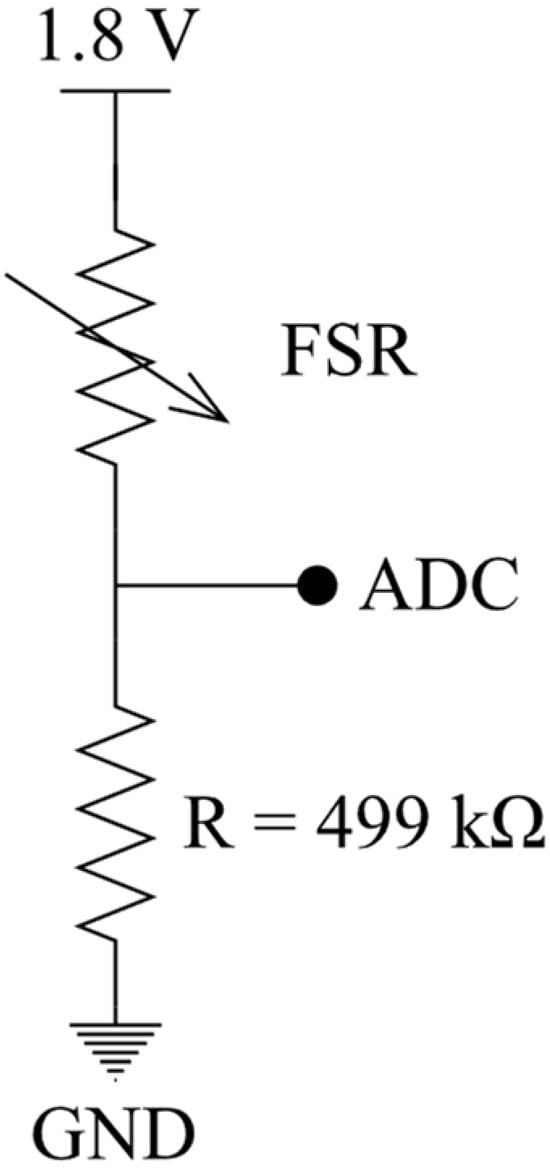

An FSR, whose electrical resistance decreases the more force is applied to its surface, is used in this work. An FSR has some advantages over strain gauges or load cells, like cost efficiency, a low profile, and excellent force mapping application (changes occur significantly when the pressure is applied to the FSR surface), and also ensures patient comfort [17,18,19]. As shown in Figure 4, to measure the force applied, a voltage divider is implemented by placing a fixed resistor (499 kΩ) in a series with the FSR, which acts as a variable resistor. By increasing the pressure on the FSR, the resistance of the FSR decreases.

Figure 4.

Reading/measuring FSR resistance.

The output voltage can be obtained using Equation (1). With the addition of the ADC, we are able to sample the electrical resistance, thereby measuring the force.

2.4. Power Management

To supply the device, we use a rechargeable 450 mAh Lithium Polymer (LiPo) battery. A LiPo battery has been chosen for our device due to its high energy density, rechargeability, and decent cycle life. A further advantage of these batteries is their light weight, flexibility, and leak resistance. Also, we incorporate a buck converter (TPS62840) to regulate the battery voltage (3.3~4.2 V) to 1.8 V in order to supply the elements that require this voltage. Using a switching converter enhances the battery life and efficiency. A battery charger (MCP73833T) charges the battery through a USB type-C connector. Moreover, an ADC measures the battery charge every 2 s. Then, through a resistor divider, the battery voltage is scaled to the micro-controller voltage for the purpose of sending a percentage level and ultimately charging status via BLE.

2.5. Accelerometer

LIS2DH12 is a low-power, high-performance 3-axis accelerometer that detects motion, tracks physical activity, and identifies unexpected movements.

2.6. Firmware

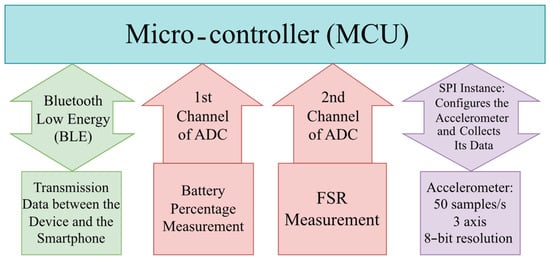

As shown in Figure 5, the data is sent through the device to a smartphone using Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) 5. It also indicates the battery percentage. The first channel of the ADC measures the battery percentage, and the second channel measures the FSR pressure. The accelerometer streams the data at 50 samples per second.

Figure 5.

Firmware flowchart depicting the overall functionality. SPI configures the accelerometer. The first channel of ADC is used for the battery percentage measurement, and the second is for the FSR measurement. Also, the firmware is responsible for data transmission through BLE between the device and the smartphone.

2.7. Body Design

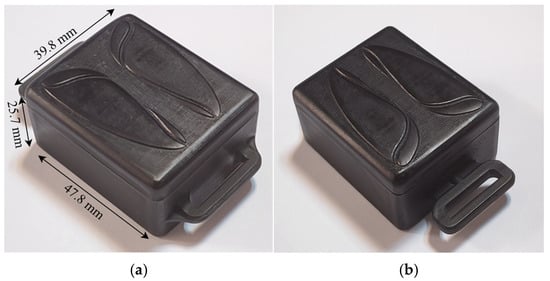

The enclosure of this device (Figure 6) is manufactured by Stereolithography (SLA) resin printing due to its high accuracy, isotropic, high thermal durability, and high finish surface [20]. The material used for printing is ABS-like (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene) resin. Although it might be a little more expensive than standard resin, it has greater impact resistance, tensile strength, and durability [21,22]. The implementation of the respiration monitoring device succeeds in delivering a sturdy, user-friendly, and efficient practical device.

Figure 6.

Final body design of the wearable device. (a) Top view of the assembled enclosure with annotated dimensions; (b) rotated top-side view showing the belt clip attachment.

3. Results and Discussion

Several devices have been developed to measure respiration rate using a variety of designs, including skin electrodes, respiration belts, and sleep-related respiratory sensors. However, the advantages of good comfort, a high Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), the possibility of the real-time monitoring and long-term detection of biological signals make sensors placed directly on the skin a suitable choice for respiratory sensors, among other types [23]. There are also several technologies for measuring pressure, including load cells, strain gauges, and FSRs. Each of these approaches has its pros and cons, and one must choose the one that produces the best results in terms of accuracy, efficiency, and cost [24,25].

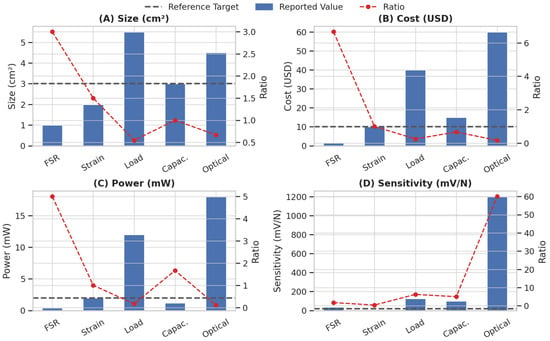

In our work, we used FSR for pressure sensing. For a further comparison of force-sensing devices and why FSR was explicitly chosen, refer to Table 1.

Table 1.

A comparison between various sensors and their features.

Figure 7 illustrates a comparative analysis of five sensor types across four key metrics: size, cost, power consumption, and sensitivity. FSRs demonstrated the smallest form factor, lowest cost, and minimal power consumption, making them highly suitable for wearable applications. Although optical sensors show the highest raw sensitivity, they perform poorly in terms of size, power, and cost. Comparing devices using FSRs with ones using strain gauges, we find that when the same force is applied to the sensor, there is a broader swing in the FSR’s output than in strain gauges. As an additional advantage, FSR technology has overload cells and strain gauges with its minimally invasive form factor, thin shape, and capability to cover a wider sensing region if needed. As stated above, as a result of the dramatic changes in the FSR resistance of FSRs with pressure, any force applied due to respiration can be easily observed. Based on all these considerations, we decided to implement an FSR into our wearable sensing device. Biosensing technologies and systems on chips play an important role in clinical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring [34,35]. As future work, artificial intelligence can be integrated into wearable FSR sensors to enable automated signal interpretation, adaptive calibration, inverse design, and improved robustness against noise and motion artifacts [36]. Advanced AI methods such as nonlinear dimensionality reduction (NLDR) [37], large language models (LLMs) for multimodal data fusion and clinical-context–aware interpretation [38], graph neural networks (GNNs) for modeling spatial–temporal dependencies across sensor networks and body locations [39], and generative adversarial networks (GANs) for realistic data augmentation, denoising, and missing-signal reconstruction [40], together with Green Learning (GL) frameworks for energy-efficient, and resource-aware on-device learning [41], can further enhance the reliability, scalability, and sustainability of FSR-based sensors. Such AI-enhanced sensors can support real-time decision making, personalized health monitoring, and large-scale deployment in everyday healthcare settings.

Figure 7.

Comparison of five sensor types (Force-Sensing Resistor, strain gauge, load cell, capacitive force sensor, optical force sensor) across different metrics. Blue bars represent reported values. Black lines indicate reference targets suitable for wearable applications. Red lines show the ratio of reported to target values, where higher ratios imply better alignment with design goals.

4. Conclusions

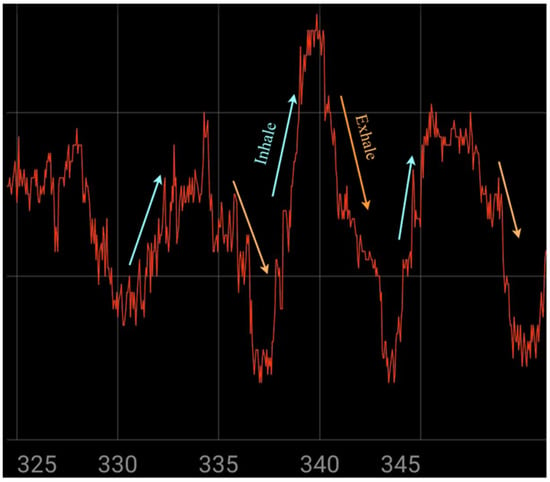

The designed respiratory monitoring system introduces a number of novel design elements and satisfies the desired functional requirements. The selection of proper elements in the structure of the sensor, as well as innovative design approaches, ensure a high resolution of 12 bits for capturing respiratory signals and a long battery life. Also, the size of the device makes it portable and convenient for patient use. Moreover, it provides a system for sending notifications and communicating between the device and its user. Figure 8 demonstrates the system’s ability to capture detailed respiratory waveforms, highlighting clear inhale and exhale phases during real-time usage, which reflects both the precision of signal acquisition and the device’s responsiveness to chest motion.

Figure 8.

Illustrating the signal during device usage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B., M.F. and Y.N.; investigation, B.B., M.F. and Y.N.; project administration, B.B.; writing—original draft preparation, B.B., M.F., S.B. and Y.T.; writing—review and editing, Y.T. and S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors used GPT-4 by OpenAI for text refinement, grammar, and spell-checking. No original research data were generated by AI, and all content was thoroughly reviewed by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Bardia Baraeinejad, Saba Babaei, and Yasin Naghshbandi were employed by the company BIOSEN Group. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Andreozzi, E.; Esposito, D.; Centracchio, J.; Bifulco, P.; Gargiulo, G.D. Respiration Monitoring via Forcecardiography Sensors. Sensors 2021, 21, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolò, A.; Massaroni, C.; Schena, E.; Sacchetti, M. The Importance of Respiratory Rate Monitoring: From Healthcare to Sport and Exercise. Sensors 2020, 20, 6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torabi, Y.; Shirani, S.; Reilly, J.P. Exploring Sensing Devices for Heart and Lung Sound Monitoring. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.12432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Park, W.H.; Borg, A. Phase-Dependent Respiratory-Motor Interactions in Reaction Time Tasks During Rhythmic Voluntary Breathing. Mot. Control 2012, 16, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- De Troyer, A.; Kirkwood, P.A.; Wilson, T.A. Respiratory Action of the Intercostal Muscles. Physiol. Rev. 2005, 85, 717–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokavee, S.; Tantrakul, V.; Pengjiam, J.; Kerdcharoen, T. A Sleep Monitoring System Using Force Sensor and an Accelerometer Sensor for Screening Sleep Apnea. In Proceedings of the 2021 13th International Conference on Knowledge and Smart Technology (KST), Hua Hin, Thailand, 21–24 January 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraeinejad, B.; Forouzesh, M.; Babaei, S.; Naghshbandi, Y.; Torabi, Y.; Fazliani, S. Clinical IoT in Practice: A Novel Design and Implementation of a Multi-Functional Digital Stethoscope for Remote Health Monitoring. TechRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanegas, E.; Igual, R.; Plaza, I. Sensing Systems for Respiration Monitoring: A Technical Systematic Review. Sensors 2020, 20, 5446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, E.J.; Arias, D.E.; Aqueveque, P.; Vilugrón, L.; Hermosilla, D.; Curtis, D.W. Monitoring Technology for Wheelchair Users with Advanced Multiple Sclerosis. In Proceedings of the 2013 35th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Osaka, Japan, 3–7 July 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.W.; Das, P.S.; Chhetry, A.; Park, J.Y. A Flexible Capacitive Pressure Sensor for Wearable Respiration Monitoring System. IEEE Sens. J. 2017, 17, 6558–6564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STMicroelectronics. MEMS Digital Output Motion Sensor: Ultra-Low-Power High-Performance 3-Axis “Femto” Accelerometer, LIS2DH12 Datasheet, Rev. 9; 2023. Available online: https://www.st.com/resource/en/datasheet/lis2dh12.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Swanson, E.C.; Weathersby, E.J.; Cagle, J.C.; Sanders, J.E. Evaluation of Force Sensing Resistors for the Measurement of Interface Pressures in Lower Limb Prosthetics. J. Biomech. Eng. 2019, 141, 101009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordic Semiconductor. nRF52832 Product Specification v1.4, Version 1.4; 10 October 2017. Available online: https://infocenter.nordicsemi.com/pdf/nRF52832_PS_v1.4.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Microchip Technology Inc. Stand-Alone Linear Li-Ion/Li-Polymer Charge Management Controller, MCP73833 Datasheet. Available online: https://ww1.microchip.com/downloads/aemDocuments/documents/OTH/ProductDocuments/DataSheets/22005b.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Venkatasetty, H.; Jeong, Y. Recent Advances in Lithium-Ion and Lithium-Polymer Batteries. In Proceedings of the Seventeenth Annual Battery Conference on Applications and Advances (Cat. No. 02TH8576), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–18 January 2002; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Texas Instruments. TPS62840 1.8-V to 6.5-V, 750-mA, 60-nA IQ Step-Down Converter, Datasheet. Available online: https://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/tps62840.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Yaniger, S. Force Sensing Resistors: A Review of the Technology. In Proceedings of the Electro International, Boston, MA, USA, 12–14 May 1991; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1991; pp. 666–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanelli, D.; Farella, E. Force Sensing Resistor and Evaluation of Technology for Wearable Body Pressure Sensing. J. Sens. 2016, 2016, 9391850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, D.; Centracchio, J.; Andreozzi, E.; Bifulco, P.; Gargiulo, G.D. Design and Evaluation of a Low-Cost Electromechanical System to Test Dynamic Performance of Force Sensors at Low Frequencies. Machines 2022, 10, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandyal, A.; Chaturvedi, I.; Wazir, I.; Raina, A.; Haq, M.I.U. 3D Printing–A Review of Processes, Materials and Applications in Industry 4.0. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022, 3, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Lee, H. Preliminary Study on Polishing SLA 3D-Printed ABS-like Resins for Surface Roughness and Glossiness Reduction. Micromachines 2020, 11, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, T.D.; Kashani, A.; Imbalzano, G.; Nguyen, K.T.; Hui, D. Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing): A Review of Materials, Methods, Applications and Challenges. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 143, 172–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, S.; Shi, Y.; Pan, L. Skin-Attachable Sensors for Biomedical Applications. Biomed. Mater. Devices 2022, 1, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; He, Y.; Wang, J. Multi-Component FBG-Based Force Sensing Systems by Comparison with Other Sensing Technologies: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 7345–7357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehly, R.; Wanderley, M.M.; van de Ven, T.; Curtil, D. In-House Development of Paper Force Sensors for Musical Applications. Comput. Music J. 2014, 38, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadeh, M.Y.; Carambat, T.D.; Arrieta, A.M. Evaluating and Modeling Force Sensing Resistors for Low Force Applications. In Proceedings of the ASME 2017 Conference on Smart Materials, Adaptive Structures and Intelligent Systems (SMASIS), Snowbird, UT, USA, 18–20 September 2017; ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 58264, p. V002T03A001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinger, A.; Wanderley, M.M. Evaluation of Commercial Force-Sensing Resistors. In Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME), Paris, France, 4–8 June 2006; Citeseer: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Castellini, C.; Ravindra, V. A Wearable Low-Cost Device Based upon Force-Sensing Resistors to Detect Single-Finger Forces. In Proceedings of the 5th IEEE RAS/EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob), São Paulo, Brazil, 12–15 August 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejos, A.L.; Patel, R.V.; Naish, M.D. Force Sensing and Its Application in Minimally Invasive Surgery and Therapy: A Survey. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2010, 224, 1435–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, I.; Hu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, W. Load Cells in Force Sensing Analysis—Theory and a Novel Application. IEEE Instrum. Meas. Mag. 2010, 13, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Xu, Q. An Overview of Micro-Force Sensing Techniques. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2015, 234, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almassri, A.M.; Wan Hasan, W.Z.; Ahmad, S.A.; Ishak, A.J.; Ghazali, A.M.; Talib, D.N.M.A.; Nasir, N.M. Pressure Sensor: State of the Art, Design, and Application for Robotic Hand. J. Sens. 2015, 2015, 846487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Shen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, W. Recent Progress in Flexible Pressure Sensor Arrays: From Design to Applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 11878–11892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, Y.; Shirani, S.; Reilly, J.P. Quantum Biosensors on Chip: A Review from Electronic and Photonic Integrated Circuits to Future Integrated Quantum Photonic Circuits. Microelectronics 2025, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinisangchi, S. A Wide-Band Frequency Domain Near Infrared Spectroscopy System on Chip. Master’s Thesis, University of California, Irvine, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Torabi, Y.; Ekhteraei, A.; Baraeinejad, B. Inverse Design of Microring Resonator-Based Glucose Biosensor Using AI Diffusion Models. Optica Open 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazifeh, A.R.; Fleischer, J.W. Manifold Learning for Personalized and Label-Free Detection of Cardiac Arrhythmias. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.16494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, Y.; Shirani, S.; Reilly, J.P. Large Language Model-Based Nonnegative Matrix Factorization for Cardiorespiratory Sound Separation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.05757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, S.; Ajorlou, H.; Mateos, G. Directed Acyclic Graph Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.12218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golkarieh, A.; Razmara, P.; Lagzian, A.; Dolatabadi, A.; Mousavirad, S.J. Semi-Supervised GAN with Hybrid Regularization and Evolutionary Hyperparameter Tuning for Accurate Melanoma Detection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movaheddrad, M.; Palmer, L.; Kuo, C. GUSL-Dehaze: A Green U-Shaped Learning Approach to Image Dehazing. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.20266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).