Abstract

The urgent need for cleaner energy sources has driven exploration into innovative and sustainable solutions. This study investigates the potential of the invasive aquatic plant, the water hyacinth, to contribute to energy recovery and support the preservation of blue carbon ecosystems through biomass removal. Employing slow pyrolysis, this study examines the influence of temperature (300–500 °C) and residence time (30–90 min) on bio-oil and biochar production in a fixed-bed reactor. Results revealed that residence time was the key operational parameter significantly influencing total liquid condensate yield, which peaked at 34.34 wt% at 400 °C after 90 min. Moisture content reveals an actual organic bio-oil yield of approximately 3.4–4.8 wt%. In contrast, biochar yield (max. 43.74 wt%) was not significantly affected by the tested parameters. The resulting bio-oil exhibited a high heating value of up to 25.84 MJ/kg, suggesting its potential as a renewable fuel. This study concludes that slow pyrolysis of invasive water hyacinth provides a dual-benefit pathway: it co-produces renewable bio-oil for energy recovery alongside a stable biochar, offering a tangible route for blue carbon sequestration. This integrated approach transforms an environmental liability into valuable resources, contributing to a cleaner environment and a more sustainable future.

1. Introduction

The escalating threat of climate change necessitates a search for sustainable technologies [1]. Blue carbon ecosystems are vital for climate change mitigation but are often degraded by aquaculture practices [2,3,4,5], which in turn promote the proliferation of invasive species like water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) [6]. Previous research has explored the thermochemical conversion of water hyacinth, but these studies have typically focused singularly on either maximizing bio-oil yield through fast pyrolysis or characterizing biochar properties for agricultural use [6,7,8]. However, few studies have applied rigorous statistical designs to quantify the operational trade-offs between liquid energy recovery and solid carbon storage specifically within a blue carbon preservation framework [8].

A clear research gap remains in systematically optimizing slow pyrolysis to balance these competing outputs. This study addresses this gap by employing a 32 full factorial design to investigate the simultaneous production of renewable energy and a stable carbon sequestration product. Unlike recent works that prioritize single-stream valorization, this research provides a statistical evaluation of how temperature and residence influence the physicochemical properties of both fractions concurrently [8]. This integrated, dual-purpose approach is critical as it embodies circular economic principles, converting an environmental liability that threatens blue carbon sinks into high-value products. By valorizing this invasive biomass, the strategy simultaneously addresses challenges in waste management, renewable energy generation, and climate action, offering a more holistic solution than single-purpose pathways [6]. Therefore, this study aims to optimize the slow pyrolysis of water hyacinth to address invasive species management, renewable energy generation, and blue carbon sequestration simultaneously.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Fresh water hyacinth was collected from Laguna de Bay, Rizal, Philippines. Leaves were separated from roots, washed, cut into 1 cm × 1 cm portions, and oven-dried at 45 °C for a minimum of 3 h before being stored in sealed containers.

2.2. Equipment

2.2.1. Pyrolysis Reactor

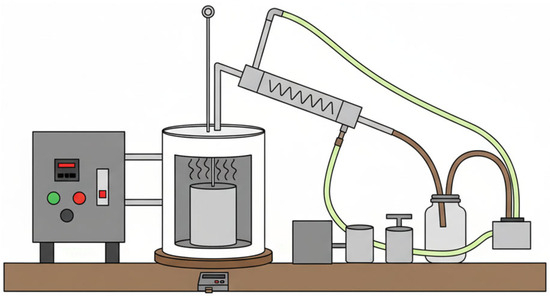

A laboratory-scale fixed-bed reactor (Figure 1), consisting of a stainless-steel pyrolysis chamber, furnace, condenser, and temperature controller, was used for all experiments.

Figure 1.

Schematic Diagram of the Fixed-Bed Pyrolysis Reactor Setup.

2.2.2. Analytical Instrument

Product mass was measured with a digital weighing scale. Bio-oil properties were analyzed using a pH meter, a portable refractometer, a bomb calorimeter (HHV), a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum Two spectrometer (FTIR), and an Ostwald viscometer. Proximate analysis was conducted at the Adamson University Technology Research and Development Center (AUTRDC) using standard methods.

2.3. Experimental Design

A 32 full factorial experimental design was implemented using Design Expert v25.0 software to investigate the main and interaction effects of temperature (300 °C, 400 °C, 500 °C) and residence time (30, 60, 90 min) on the pyrolysis process. The measured responses included bio-oil yield, biochar yield, and the physicochemical properties of the products. A total of 27 runs, consisting of three replicates for each of the nine experimental conditions, were conducted in a randomized order to minimize systematic error. For statistical analysis, replicates were treated as independent experimental units to allow for the estimation of pure error and lack-of-fit within the ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) model. All reported results for yields and physicochemical properties represent the mean ± standard deviation of these three independent replicates. Each run utilized 60 g of feedstock, with the experimental matrix detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental design for slow pyrolysis.

2.4. Pyrolysis Procedure

For each run, approximately 60 g of dried water hyacinth was loaded into the sealed reactor and heated to the target temperature. The residence time was measured from the point where the desired temperature was reached. Volatiles were condensed to collect bio-oil, and the solid biochar was collected and weighed after the reactor cooled.

2.5. Product Analysis

2.5.1. Bio-Oil and Biochar Yield Determination

The mass of the bio-oil and biochar produced in each run was measured using a digital analytical balance. The yields were calculated as a percentage of the initial mass of the dried water hyacinth feedstock using the following equations:

Bio-oil yield (wt%) = (mass of bio-oil/mass of dried water hyacinth) × 100,

Biochar yield (wt%) = (mass of biochar/mass of dried water hyacinth) × 100,

2.5.2. Bio-Oil Characterization

Collected bio-oil was analyzed for its physical and chemical properties. Density was determined gravimetrically, while pH and refractive index were measured using indicator paper and a portable refractometer, respectively.

Higher Heating Value (HHV) was measured with a bomb calorimeter and calculated with an empirical formula [9] (Equations (3) and (4)).

HHV (cal/g) = 25.284M + 30.572A + 62.172VM + 138.117FC − 2890,

HHV (MJ/kg) = HHV (cal/g) × 0.004817

In these equations, M, A, VM, and FC represent the weight percentages (wt%) of moisture, ash, volatile matter, and fixed carbon, respectively, obtained from proximate analysis. Equation (4) converts the calculated HHV from calories per gram (cal/g) to megajoules per kilogram (MJ/kg).

Kinematic viscosity was calculated from dynamic viscosity and density measurements. FTIR analysis identified functional groups. Additionally, a modified proximate analysis was conducted on the bio-oil to characterize the organic fraction’s thermal stability. Moisture was determined directly, while ash, volatile matter, and fixed carbon were analyzed on the dried organic residue to assess coking tendency and volatility. Sulfur content was also determined.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

A two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with a 95% confidence interval was used to determine the statistical significance of temperature and residence time on all measured responses. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Slow Pyrolysis of Water Hyacinth as a New Avenue for Blue Carbon and Renewable Energy

Unsustainable aquaculture practices threaten blue carbon sinks [10]. This study explores slow pyrolysis of invasive water hyacinth to enhance blue carbon storage and generate renewable energy, bridging a gap in current research [11]. This approach aims to convert an environmental liability into a valuable resource for climate change mitigation.

3.2. Biochar Yield: Implications for Blue Carbon Sequestration

Although the tested parameters did not show a statistically significant effect on yield, pyrolysis at temperatures between 300 °C and 500 °C is known to decrease atomic H/C and O/C ratios in water hyacinth biochar, indicating the likely formation of stable aromatic structures. Although specific elemental (CHNSO) and surface area (BET) analyses were not conducted in this study to empirically verify recalcitrance, the thermal conditions applied are consistent with literature protocols for producing stable carbon [12]. Therefore, while the biochar yield indicates a significant carbon sink potential, actual sequestration capacity and long-term stability remain theoretical pending further physicochemical characterization.

3.3. Bio-Oil Yield: Implications for Energy Recovery

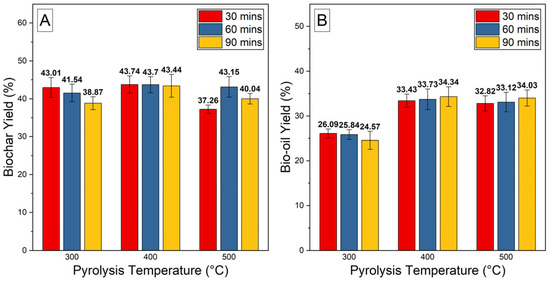

As shown in Figure 2B, extending the residence time significantly increased the total liquid condensate yield, with maximums of 34.34 wt% (400 °C) and 34.03 wt% (500 °C) achieved at 90 min. However, given the high moisture content determined in the proximate analysis (86–90%), the actual organic phase yield is significantly lower. After adjusting for water content, the estimated organic bio-oil yield ranges from approximately 3.4 wt% to 4.8 wt%. While this organic fraction is low compared to terrestrial woody biomass, it aligns with literature benchmarks for high-moisture aquatic macrophytes (typically <10% organic yield in slow pyrolysis) [13,14]. The high aqueous yield is attributed to the enhanced thermal decomposition of biomass polymers and significant dehydration reactions contributing to the aqueous phase [13]. Consequently, the liquid product requires significant dewatering or upgradation to rival yields from conventional lignocellulosic feedstocks [15], highlighting water hyacinth’s potential for renewable fuel production. The bio-oil viscosity falls within range of ASTM D7544 pyrolysis liquid grades [16], although the high acidity and moisture content deviate from EN 14214 biodiesel standards [17], indicating a need for upgrading prior to direct engine application.

Figure 2.

(A) Biochar yield and (B) Bio-oil yield vs. temperature and residence time.

3.4. Bio-Oil Characterization: Properties and Potential Applications

3.4.1. Physical Properties: Density, pH, Viscosity, and Refractive Index

The physical properties of bio-oil are summarized in Table 2. The density (1003.21–1023.11 kg/m3) was higher than conventional fuels [18,19]. The bio-oil was acidic (pH 3), a common trait due to the presence of organic acids [20]. Viscosity (18.7–18.9 cSt) was considerably higher than diesel fuel [21], while the refractive index (23.5–29.7 Brix%) indicated a high concentration of dissolved organic solids [22].

Table 2.

Physical properties of bio-oil.

3.4.2. Chemical Properties: HHV, Functional Groups, and Elemental Composition

As shown in Table 3, the bio-oil’s HHV ranged from 23.37 to 25.84 MJ/kg, which is comparable to other lignocellulosic bio-oils [23] but lower than conventional diesel [24].

Table 3.

HHV of bio-oil at different temperatures and residence times.

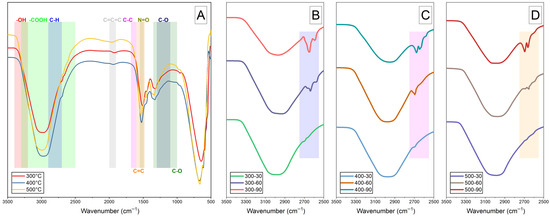

The FTIR spectra (Figure 3 and Table 4) confirmed the presence of a complex mixture of oxygenated compounds. Semi-quantitative analysis reveals that the spectra are dominated by a broad, intense O-H stretching band (3400–3200 cm−1), consistent with the high-water content (>86 wt%) and the presence of phenols and alcohols derived from lignin depolymerization. The distinct peaks in the carbonyl region (1700 cm−1 range) and carboxylic acid region (3300–2500 cm−1) correlate with the low pH observed (Table 2), indicating a high concentration of organic acids. These functional groups are typical for raw bio-oils and suggest potential as a chemical feedstock [25], though the high degree of oxygenation implies low chemical stability.

Figure 3.

FT-IR spectra of bio-oil derived from water hyacinth pyrolysis under different conditions: (A) varying temperatures at a constant residence time of 30 min; (B) varying residence times at 300 °C; (C) varying residence times at 400 °C; (D) varying residence times at 500 °C.

Table 4.

Major absorption bands and functional groups identified in FT-IR analysis.

The bio-oil had high moisture (86–90 wt%) and volatile matter (95.69–99.28 wt%), with low ash (<0.25 wt%) beneficial for combustion [26] (Table 5). However, the presence of carboxylic acids and oxygenated groups identified in the FTIR analysis poses significant challenges regarding aging and storage stability. These groups tend to undergo repolymerization over time, increasing viscosity and potentially causing phase separation. High moisture content is a known characteristic of pyrolysis oils that can impact storage stability [23], and the acidity necessitates corrosion-resistant storage or immediate upgrading Despite FTIR providing functional group classification, the lack of Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis in this study limits the identification of specific molecular compounds, which is a necessary step for designing precise upgrading catalysts.

Table 5.

Proximate Analysis of Bio-oil (Dry Basis for Ash, FC, VCM).

3.5. Statistical Analysis of Pyrolysis Parameters

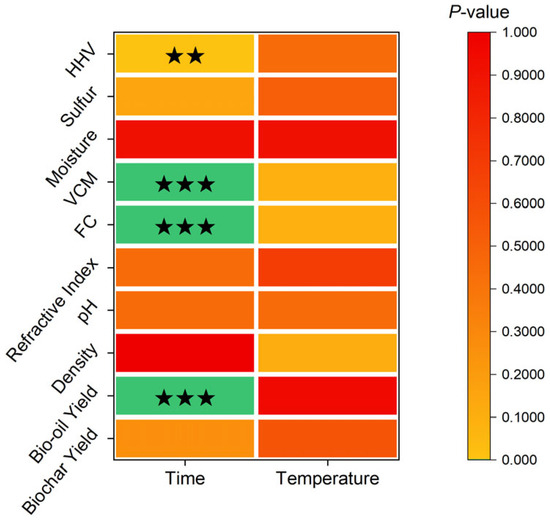

The ANOVA results (Figure 4) show that residence time had a statistically significant effect on bio-oil yield (p < 0.0005) and HHV (p < 0.005). Both temperature and residence time significantly affected fixed carbon and volatile matter content (p < 0.0005). Conversely, neither parameter significantly influenced biochar yield, density, pH, refractive index, moisture, or sulfur content (p > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Heatmap of p-values from two-way ANOVA. Green indicates a statistically significant effect (p < 0.0005), while the yellow-to-red gradient indicates less significance. Stars denote confidence levels: ★★★ (p < 0.0005), ★★ (p < 0.005).

3.6. Harnessing an Invasive Species for Environmental Benefits: A Dual Strategy for Blue Carbon and Energy Recovery

This study demonstrates that slow pyrolysis effectively converts invasive water hyacinth into two valuable products. The resulting biochar offers a stable method for blue carbon sequestration, enhancing soil health in coastal ecosystems. Concurrently, bio-oil represents a viable renewable energy source and chemical feedstock. This dual strategy aligns with circular economic principles by transforming a problematic waste stream into a resource, addressing climate change, and managing an invasive species.

3.7. Future Directions

Further research is recommended to:

- Explore a wider range of parameters to optimize product yields and quality.

- Conduct in-depth biochar characterization, specifically elemental analysis (CHNSO) to determine H/C ratios and BET analysis for surface porosity, followed by field trials to assess its long-term carbon sequestration potential.

- Investigate bio-oil upgrading techniques to improve its fuel properties and isolate valuable chemical compounds.

- Perform comprehensive techno-economic (TEA) and life-cycle assessments (LCA) to evaluate the process’s overall viability and environmental impact.

- Address the scalability of the process and its integration with existing waste management infrastructure.

- Apply similar pyrolysis strategies to other invasive aquatic species to expand the feedstock base for resource recovery.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the parametric effects of slow pyrolysis on water hyacinth. This preliminary laboratory-scale study investigated the parametric effects of slow pyrolysis on water hyacinth. The conditions favoring maximum liquid condensate production were identified at 400 °C with a 90-min residence time, achieving a maximum total yield of 34.34 wt% with an HHV of 25.84 MJ/kg. Regarding environmental benefits, the process-maintained biochar yields between 38 wt% and 43 wt% across all tested parameters, providing a quantifiable solid residue for potential carbon sequestration. These results indicate that extending the residence time significantly enhances liquid condensate production while retaining substantial solid carbon mass. However, strictly interpreting these findings as a deployable solution is premature. Future research must conduct rigorous energy balance calculations, techno-economic assessments, and biochar stability testing to validate the system’s efficiency. Additionally, the bio-oil requires upgrading to address high moisture and acidity. Thus, this work serves as a foundational step, identifying promising operational trends for a dual-benefit strategy for managing invasive biomass.

Author Contributions

P.P.T., E.M.C., T.C.G., W.M. and I.J.M.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, and writing—original draft. R.V.R. and E.H.: conceptualization, data curation, project administration, supervision, validation, and writing—review & editing. R.J.P.L.: visualization and writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Latiza, R.J.P.; Rubi, R.V. Circular Economy Integration in 1G + 2G Sugarcane Bioethanol Production: Application of Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage, Closed-Loop Systems, and Waste Valorization for Sustainability. Appl. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 18, 7448. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Jahan, F. A Systematic Review Of Blue Carbon Potential in Coastal Marshlands: Opportunities For Climate Change Mitigation And Ecosystem Resilience. Front. Appl. Eng. Technol. 2025, 2, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latiza, R.J.P.; Mustafa, A.; Delos Reyes, K.; Nebres, K.L.; Abrogena, S.L.; Rubi, R.V. Optimization, characterization, reversible thermodynamically favored adsorption, and mechanistic insights into low-cost mesoporous Fe-doped kapok fibers for efficient caffeine removal from water. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2025, 60, 1643–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latiza, R.J.P.; Olay, J.; Eguico, C.; Yan, R.J.; Rubi, R.V. Environmental applications of carbon dots: Addressing microplastics, air and water pollution. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 17, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Friess, D.A.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xin, R.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y. Restoring mangroves lost by aquaculture offers large blue carbon benefits. One Earth 2025, 8, 101149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abba, A.; Sankarannair, S. Global impact of water hyacinth (Eichhornia Crassipes) on rural communities and mitigation strategies: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 43616–43632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Q.; Song, Z.; Zhang, X.; He, D.; Guo, L.; Van Zwieten, L.; Yu, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Fang, Y.; et al. Organic blue carbon sequestration in vegetated coastal wetlands: Processes and influencing factors. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2024, 255, 104853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, P.P.; Kafle, S.; Park, S.; Kim, S.J.; Cho, L.; Kim, D.H. Advancements in sustainable thermochemical conversion of agricultural crop residues: A systematic review of technical progress, applications, perspectives, and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 202, 114723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilakazi, L.; Madyira, D. Estimation of gross calorific value of coal: A literature review. Int. J. Coal Prep. Util. 2024, 45, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, X.; Gao, L.; Liang, J.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Guo, Y.; Liang, S. Carbon footprint assessment and reduction strategies for aquaculture: A review. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2025, 56, e13117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassa, Y.; Amare, A.; Nega, T.; Alem, T.; Gedefaw, M.; Chala, B.; Freyer, B.; Waldmann, B.; Fentie, T.; Mulu, T.; et al. Water hyacinth conversion to biochar for soil nutrient enhancement in improving agricultural product. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoudho, K.N.; Khan, T.H.; Ara, U.R.; Khan, M.R.; Shawon, Z.B.Z.; Hoque, M.E. Biochar in global carbon cycle: Towards sustainable development goals. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2024, 8, 100409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminaathan, P.; Saravanan, A.; Thamarai, P. Utilization of bioresources for high-value bioproducts production: Sustainability and perspectives in circular bioeconomy. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 63, 103672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Kumar, V.T.; Krishna, B.B.; Bhaskar, T. Comprehensive pyrolysis investigation of Lemongrass and Tagetes minuta residual biomass: Bio-oil composition and biochar physicochemical properties. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2024, 15, 28651–28666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, B. Novel techniques in bio-oil production through catalytic pyrolysis of waste biomass: Effective parameters, innovations, and techno-economic analysis. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 103, e25587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D7544-12R17; Specification for Pyrolysis Liquid Biofuel. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- D6751-23A; Specification for Biodiesel Fuel Blend Stock (B100) for Middle Distillate Fuels. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- Jia, J.; Deng, N.; Liu, T.; He, G.; Hu, B. A study on the production of low-viscosity bio-oil from rapeseed by magnetic field pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2024, 177, 106292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghannam, M.; Selim, M.Y.E. Viscoelastic performance evaluation of petrol oil and different macromolecule materials. Int. J. Thermofluids 2024, 22, 100596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Liu, Y.; Cao, X.; Yang, P.; Cheng, L.; Ghazani, M.S.; Suota, M.J.; Bi, X. Microwave catalytic pyrolysis of solid digestate for high quality bio-oil and biochar. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2024, 182, 106683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roschat, W.; Phewphong, S.; Inthachai, S.; Donpamee, K.; Phudeetip, N.; Leelatam, T.; Moonsin, P.; Katekaew, S.; Namwongsa, K.; Yoosuk, B.; et al. A highly efficient and cost-effective liquid biofuel for agricultural diesel engines from ternary blending of distilled Yang-Na (Dipterocarpus alatus) oil, waste cooking oil biodiesel, and petroleum diesel oil. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 48, 100540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, A.; Liakos, D.; Pfisterer, U.; Moustaka-Gouni, M.; Karonis, D.; Bezergianni, S. Impact of hydrogenation on miscibility of fast pyrolysis bio-oil with refinery fractions towards bio-oil refinery integration. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 151, 106171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Charoenkal, K.; Yuan, Q.; Cao, H. Hydrothermal bio-oil yield and higher heating value of high moisture and lipid biomass: Machine learning modeling and feature response behavior analysis. J. Energy Inst. 2024, 117, 101859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Si, B.; Summers, S.; Zhang, Y. Renewable diesel blends production from hydrothermal liquefaction of food waste: A novel approach coupling fractional distillation and emulsification. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 314, 118716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, Z.; Chen, T.; Jiang, S.; Evrendilek, F.; Huang, S.; Tang, X.; Ding, Z.; He, Y.; Xie, W.; et al. Energetic, bio-oil, biochar, and ash performances of co-pyrolysis-gasification of textile dyeing sludge and Chinese medicine residues in response to K2CO3, atmosphere type, blend ratio, and temperature. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 136, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prayoga, M.Z.E.; Adelia, N.; Prismantoko, A.; Romelan, R.; Kuswa, F.M.; Solikhah, M.D.; Darmawan, A.; Arifin, Z.; Prasetyo, B.T.; Aziz, M.; et al. Experimental investigation of slagging and fouling in co-combustion of bituminous coal and sorghum waste: Insights into ash morphology and mineralogy. Fuel 2025, 385, 134109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).