(Electro)catalytic and Sensing Properties of Redox-Active Nanoparticles with Peroxidase-like Activity †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Instrumentation

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Synthesis

2.3.2. Electrochemical Investigations of the Prussian Blue Modified Electrodes

2.3.3. Investigation of Peroxidase-like Activity

3. Results and Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TMB | 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine |

| DC | Direct current |

References

- Wang, Y.; Liang, M.; Wei, T. Types of Nanozymes: Materials and Activities; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 41–77. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Zhuang, J.; Nie, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, N.; Wang, T.; Feng, J.; Yang, D.; Perrett, S.; et al. Intrinsic peroxidase-like activity of ferromagnetic nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007, 2, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Bao, S.; Yao, L.; Fu, X.; Yu, Y.; Lyu, H.; Pang, H.; Guo, S.; Zhang, H.; et al. Cerium oxide nanoparticles in wound care: A review of mechanisms and therapeutic applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1404651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephen Inbaraj, B.; Chen, B.-H. An overview on recent in vivo biological application of cerium oxide nanoparticles. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 15, 558–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Huang, C.; Li, Y.; Kong, D.; Shen, W.; Tang, S. Modification and application of Fe3O4 nanozymes in analytical chemistry: A review. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 107820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Liang, X.; Xu, Q.; Du, L.; Qin, J. A review of a colorimetric biosensor based on Fe3O4 nanozymes for food safety detection. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2025, 417, 1713–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Tan, Z.; Leng, W.; Chen, Y.-C.; Zhang, S.; Lo, B.T.W.; Yung, K.K.L.; Peng, Y.-K. Chemical state tuning of surface Ce species on pristine CeO2 with 2400% boosting in peroxidase-like activity for glucose detection. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 7897–7900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Shen, L.; Ma, J.; Ma, H.; Zhu, N. Recent Advances of Prussian Blue-Based Wearable Biosensors for Healthcare. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos-Peralta, Y.; Antuch, M. Review—Prussian Blue and Its Analogs as Appealing Materials for Electrochemical Sensing and Biosensing. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 037510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

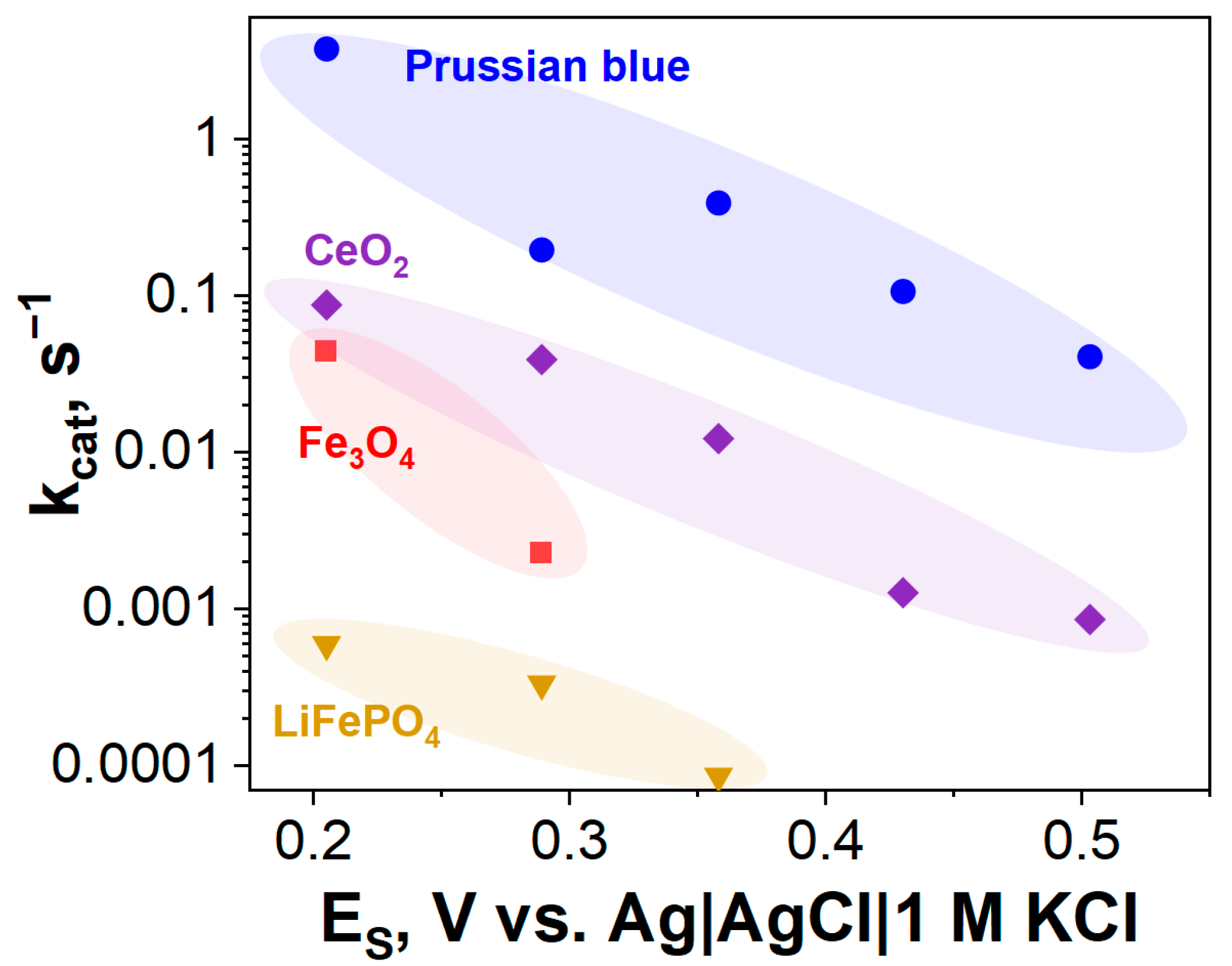

- Komkova, M.A.; Shneiderman, A.A.; Povaga, E.S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Kustov, A.L.; Yang, C.; Wei, H.; Karyakin, A.A. Peculiarities of Redox Catalysis with Peroxidase-Like Nanozymes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 40964–40973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Lin, S.; Muhammad, F.; Lin, Y.W.; Wei, H. Rationally Modulate the Oxidase-like Activity of Nanoceria for Self-Regulated Bioassays. ACS Sensors 2016, 1, 1336–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

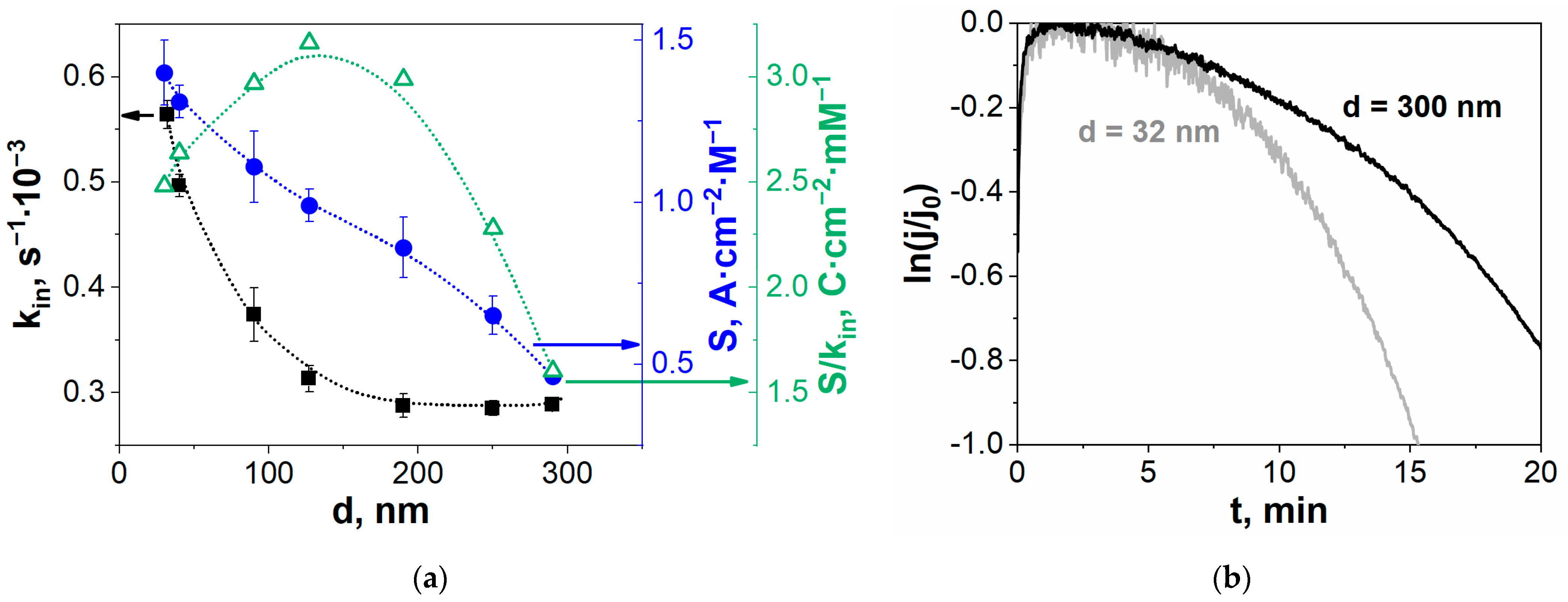

- Komkova, M.A.; Zarochintsev, A.A.; Karyakina, E.E.; Karyakin, A.A. Electrochemical and sensing properties of Prussian Blue based nanozymes “artificial peroxidase”. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2020, 872, 114048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komkova, M.A.; Karpova, E.V.; Sukhorukov, G.A.; Sadovnikov, A.A.; Karyakin, A.A. Estimation of Continuity of Electroactive Inorganic Films Based on Apparent Anti-Ohmic Trend in Their Charge Transfer Resistance. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 219, 588–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shneiderman, A.A.; Povaga, E.S.; Komkova, M.A.; Karyakin, A.A. (Electro)catalytic and Sensing Properties of Redox-Active Nanoparticles with Peroxidase-like Activity. Eng. Proc. 2025, 118, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECSA-12-26495

Shneiderman AA, Povaga ES, Komkova MA, Karyakin AA. (Electro)catalytic and Sensing Properties of Redox-Active Nanoparticles with Peroxidase-like Activity. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 118(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECSA-12-26495

Chicago/Turabian StyleShneiderman, Aleksandra A., Elena S. Povaga, Maria A. Komkova, and Arkady A. Karyakin. 2025. "(Electro)catalytic and Sensing Properties of Redox-Active Nanoparticles with Peroxidase-like Activity" Engineering Proceedings 118, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECSA-12-26495

APA StyleShneiderman, A. A., Povaga, E. S., Komkova, M. A., & Karyakin, A. A. (2025). (Electro)catalytic and Sensing Properties of Redox-Active Nanoparticles with Peroxidase-like Activity. Engineering Proceedings, 118(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECSA-12-26495