Abstract

In pharmaceutical and biomedical industries, manual handling of dangerous chemicals is a leading cause of hazardous exposure to chemicals, toxic burning, and chemical contamination. To counteract these risks, we proposed a gesture-controlled bionic hand system to mimic human finger movements for safe and contactless chemical handling. This innovation system uses an ESP32 microcontroller to decode the hand gestures that are detected by the system using computer vision via an integrated camera. A PWM servo driver converts these movements to motor commands such that accurate movements of the fingers can be achieved. Teflon and other corrosion-proof materials are utilized in the 3D printing of the bionic hand in order to withstand corrosive conditions. This new, low-cost, and non-surgical approach replaces the EMG sensors, gives real-time control, and enhances industrial and laboratory process safety. The project is a major milestone in the application of robotics and AI for automation and risk reduction in dangerous environments.

1. Introduction

In the biomedical and pharmaceutical industries, manual handling of toxic chemicals is particularly dangerous and can involve toxic exposure, burns, and cross-contamination [1]. Conventional safety measures may be inadequate in dynamic processes where precise or gentle handling of equipment is needed. Accurate hand gesture recognition systems are now feasible thanks to recent advancements in real-time computer vision and artificial intelligence [2]. Robotic mechanisms that imitate the finger movement patterns of the human hand are ideal for these kinds of systems. These kinds of systems are perfect for use with robotic mechanisms that mimic the patterns of finger movement found in the human hand.

Gesture-controlled systems are a less invasive and better choice than electromyography (EMG)-based systems. EMG-based systems need direct skin contact and have complex signal processing [3]. Furthermore, artificial intelligence and robotics integration have offered the choice to create low-cost prosthetics with advanced control features that were previously only possible using high-end solutions [4]. These devices not only provide security but also increase efficiency by reducing human intervention in hazard zones [5]. This initiative aims to bridge the gap between human dexterity and industrial automation through smart, gesture-controlled robotic systems towards intelligent manufacturing procedures and safer working conditions [6].

This project aims to develop a gesture-controlled bionic hand system as a solution for handling chemicals, offering safe contactless handling of hazardous materials in manufacturing and laboratory settings [7]. An ESP32 microcontroller is used in this project as a processor for hand gesture data because of its dual-core design, low cost, and integration of Wi-Fi and Bluetooth [8]. The movement of the hand is detected by a camera module and processed with computer vision methods and translated into servo commands using a pulse wave modulation (PWM) servo driver to operate the bionic hand with precision [9].

2. Materials and Methods

The design is centered on modularity and ease of assembly, with quick maintenance and upgrading options.

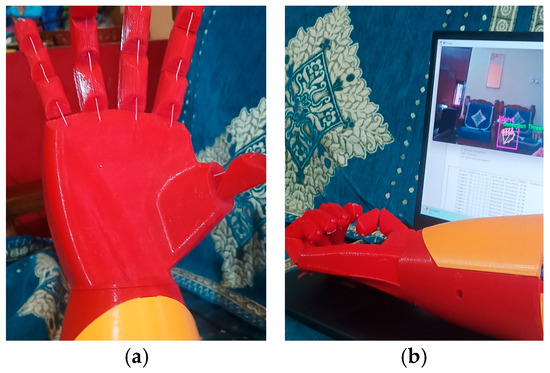

The bionic hand is 3D-printed with corrosion-resistant materials; Teflon (PTFE) is also used, which is renowned for its ideal chemical and thermal resistance. Each finger’s three segments, which match the phalanges and control the body’s natural flexing and gripping movements, are included in the anthropomorphic finger arrangement. The palm contains the servo driver, ESP 32 microcontroller (Shanghai, China), and other electronics. When moving, internal cable management prevents the cables from tangling or breaking.

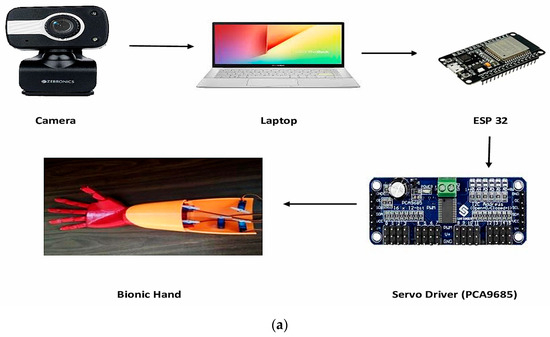

The mechanical system functions by scanning hand movements by means of a camera that captures the real-time movement. These inputs are then processed by computer vision algorithms to recognize certain movements. When a gesture is recognized, it is transmitted in the form of a control signal to the ESP32 microcontroller. The ESP32 deciphers the command and transmits proper signals to a PWM servo driver, which activates the respective servomotors as shown in Figure 1. The finger is controlled by each motor via nylon tendons, and the bionic hand is designed to replicate natural extension and flexing. The system is calibrated for proper and responsive finger control after assembly. The overall block and circuit diagrams are shown in Figure 1a,b.

Figure 1.

(a) Block diagram; (b) circuit diagram.

3. Results and Discussions

The gesture-controlled bionic hand converts hand gestures into digital signals to regulate finger movements. It is possible to have the thumb, index, middle, ring, and pinky fingers open or closed. These states are captured by a camera and processed by computer vision. The result is a 5-bit digital output, where each bit represents the state of a finger (1 for open, 0 for closed). In response to this binary command, the ESP32 microcontroller activates the corresponding servomotors, simulating the hand gesture. Each bit of the 5-bit digital output generated by the identified gesture controls a servomotor. One finger of the bionic hand is matched and paired with each servo. When the servo is set to a value of 1, the finger is in the open position; when it is set to a value of 0, the finger is in the closed position. This makes it possible to control specific finger movements in real time using user gestures. Table 1 shows how digital outputs are mapped to servomotor states.

Table 1.

Mapping of 5-bit digital output to individual servomotor ON/OFF states.

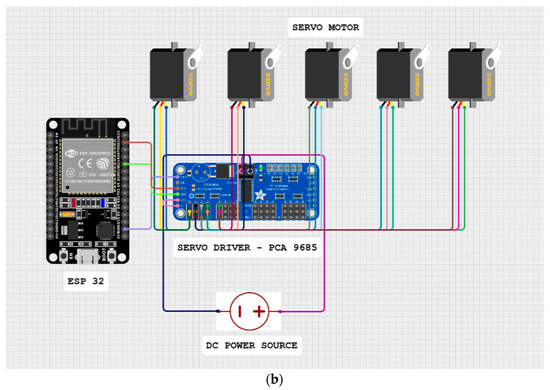

As seen in Figure 2, the system detects hand gestures using real-time computer vision. Red dots indicate the joint positions of each finger in the right hand, which is captured and subjected to keypoint detection analysis. The corresponding digital output is simultaneously shown as a 5-element binary array in the Python 3.11 console.

Figure 2.

IDLE shell window.

An individual element in the array represents a finger in the following order: thumb, index, middle, ring, and pinky. Here, 1 indicates an open finger state, and 0 indicates a closed state. The consistent output of [1, 1, 1, 1, 1] is used to identify each finger as open.

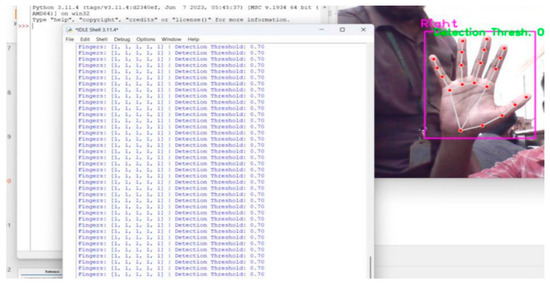

By using a camera to detect finger positions, the bionic hand mimics human gestures. As seen in Figure 3a, all fingers are in the open position when the command is [1, 1, 1, 1, 1]. Similarly, as shown in Figure 3b, a command of [0, 0, 0, 0, 0] closes all fingers.

Figure 3.

(a) Bionic hand in fully open position (command: 11111); (b) bionic hand in fully closed position (command: 00000).

By transmitting mixed binary values, such as [1, 0, 1, 0, 1], the system can also recognize partial gestures, allowing for individual finger movement. These binary values are decoded by the ESP32 microcontroller, which then transmits the appropriate signals to the servomotors, which use tendon-driven.

Moreover, experiments with various hand postures demonstrated that the system could recognize both simple and complex patterns with high accuracy, which are shown in Table 2. The commonly used gestures “all fingers open” and “all fingers closed” had almost perfect recognition within 210–220 ms, which made the response seem instantaneous to the user. Even for more complex gestures such as “thumb only” or blended finger displays, detection performance was still stellar (~94% accuracy) with a small increase in processing time (250–280 ms). This further solidifies the prototype’s reliable real-time performance for secure and efficient robotic control.

Table 2.

System accuracy and response time evaluation.

4. Conclusions

The gesture-controlled bionic hand developed in this project offers a reliable, cost-effective, and secure alternative to handling hazardous chemicals by hand. To precisely mimic human hand movements in real time, it combines camera-based gesture detection, ESP32 microcontroller logic, and precise servomotor actuation. This innovative system significantly reduces the risk of chemical exposure while improving safety in laboratory and industrial environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization of the work was done by T.D.B. and S.R.; methodology, validation and writing—original draft preparation were done by S.G., G.N. and D.F.; review and editing is done by T.D.B. and S.R.; supervision was done by T.D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cmiosh, I.I.P.; Odesola, A.S.; Ekpenkhio, J.E. Chemical Exposure in Workplace Environments: Assessing Health Risks and Developing Safety Measures. Int. J. Res. Innov. Appl. Sci. 2024, IX, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, A.; Kumar, R.; Singh, S.K. Hand Gesture Recognition Using Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Emerging Smart Computing and Informatics (ESCI), Pune, India, 12–14 March 2020; pp. 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Suhaeb, S.; Risal, A. Implementation of ESP32-Based Web Host For Control and Monitoring of Robotic Arm. J. Embed. Syst. Secur. Intell. Syst. 2024, 5, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, J.; Lu, S. Real-Time Servo Motor Control Using ESP32 and IoT Framework. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Systems and Informatics (ICSAI), Kunming, China, 10–12 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Oskoei, M.A.; Hu, H. Myoelectric Control Systems—A Survey. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 57, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, N.K. Corrosion Resistance of PTFE and Its Applications in Chemical Industry. J. Fluoropolymer Appl. 2020, 8, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Israr, A.; Satti, A.M. Artificial Hands for Rehabilitation: Design and Control Techniques. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 115698–115712. [Google Scholar]

- Sujana, I.N.; Sukor, J.A.; Jalani, J.; Sali, F.N.; Rejab, S.M. Cost-Effective Prosthetic Hand for Amputees: Challenges and Practical Implementation. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2023, 15, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Choi, H.; Kim, J. Development of a 3D Printed Robotic Hand with Gesture Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Soft Robotics (RoboSoft), New Haven, CT, USA, 15 May–15 July 2020; pp. 414–419. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).