Abstract

Precision agriculture is dependent on precise crop identification to maximize resource utilization and enhance yield forecasting. This paper investigates the use of Vision Transformers (ViTs) for crop classification from high-resolution satellite images. In contrast to traditional deep learning models, ViTs use self-attention mechanisms to capture intricate spatial relationships and improve feature representation. The envisioned framework combines preprocessed multispectral satellite imagery with a Vision Transformer model that is optimized to classify heterogeneous crop types more accurately. Experimental outcomes confirm that ViTs are superior to conventional Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) in processing big agricultural datasets, yielding better classification accuracy. The proposed model was tested on a multispectral satellite image from Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8. The results show that ViTs efficiently captured long-range dependencies and intricate spatial patterns and attained a high classification accuracy of 94.6% and a Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.91. The incorporation of multispectral characteristics like NDVI and EVI also improved model performance, allowing for improved discrimination between crops with comparable spectral signatures. The results highlight the applicability of Vision Transformers in remote sensing for sustainable and data-centric precision agriculture. Even with the improvements made in this study, issues like high computational expense, data annotation needs, and environmental fluctuations are still major hurdles to widespread deployment.

1. Introduction

Precision agriculture has emerged as a transformative approach in modern farming, leveraging advanced technologies to optimize resource utilization, enhance crop yield, and ensure sustainable agricultural practices [1]. A fundamental aspect of precision agriculture is accurate crop identification, which aids in monitoring crop health, predicting yields, and implementing data-driven decision-making processes. Conventional crop classification approaches are based on field surveys by hand or traditional machine learning algorithms, which tend to lack scalability and accuracy [2]. The combination of satellite imaging with sophisticated deep learning methods holds the key to effective and high-accuracy crop identification [3]. Figure 1 shows the important keywords used in remote sensing.

Figure 1.

Some important keywords used in remote sensing (Figure highlights the most frequently appearing research themes, with larger and darker-colored terms representing higher relevance and stronger co-occurrence frequency).

New developments in computer vision, specifically deep learning architectures, have dramatically enhanced the precision of agricultural remote sensing applications [4]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have already been applied extensively to crop classification, but their limited receptive field and susceptibility to long-range dependencies limit their performance in heavy-tailed agricultural scenes [5]. To address these issues, Vision Transformers (ViTs) have proven to be a strong contender, with enhanced spatial feature extraction and better representation learning capabilities. Vision Transformers utilize self-attention to process global relations between image elements and achieve top performance in satellite image analysis [6]. The capabilities of ViTs exceed local areas of attention because they excel at learning complicated spatial structures needed for crop type discrimination. The ability to process large agricultural datasets while gaining contextual knowledge improves crop classification precision which leads to more dependable precision agriculture solutions [7]. Satellite imagery analyzed with ViTs produces superior outcomes than regular procedures because of multiple advantages. Big agricultural areas can portray their expansive crop status through real-time satellite imaging which delivers broad viewing capabilities [8]. This paper demonstrates how the combination of multispectral and hyperspectral data enables the method to extract vital vegetation indices and spectral signatures which identify different crop species. Real-time use of these numerous data sources with ViTs produces better crop classification systems that demonstrate enhanced stability. This paper presents a framework built on Vision Transformers which can be used for satellite-image-based crop classification [2]. The high-resolution agricultural datasets need multiple spectral bands because this training enables better classification accuracy. The performance evaluation of ViTs and CNN-based architectures happens through extensive testing experiments designed to examine their effectiveness in real farming situations. The proposed system aids the progress of intelligent agricultural techniques through its delivery of accurate crop area identification capabilities to farmers and policymakers [9]. Although Vision Transformers (ViTs) [10] have been extensively applied in remote sensing, including multispectral and hyperspectral imagery, most studies focus on generic land-use or limited crop types. This work introduces a novel ViT-based framework specifically designed for crop recognition in precision agriculture. By integrating multispectral features with vegetation indices (NDVI, EVI), the model enhances discrimination among spectrally similar crops and achieves higher accuracy than CNN-based approaches. Validation on real agricultural datasets highlights its robustness and contribution to sustainable crop monitoring.

2. Literature Review

Remote sensing and machine learning in crop classification are large points of research; however, a few problems still exist. Bargiel [11] described an approach that used radar time-series and crop phenology together, but the single use of SAR data rendered the method less universally applicable compared to those surveyed in this article. Panigrahi et al. [12] compared several supervised ML regression models (M5 model tree and gradient-enhanced tree) through crop yield prediction, which achieved good performance but showed that they could not easily handle the high-dimensional multispectral data. Patil et al. [13] compared ML approaches to remote sensing yield prediction; however, their traditional ML models were not able to reflect nonlinearity in large-scale data.

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) have demonstrated significant effectiveness in crop monitoring, particularly for tasks involving pattern recognition, yield estimation, and stress detection. ANNs were used by Shankar et al. [14] to estimate the effect of nutrients on the growth of rice, since they obtained better results than linear models, but often required a lot of tuning and labeled data. You et al. [15] introduced deep Gaussian processes to the crop yield prediction utilizing satellite imagery where it showed an improvement in prediction with reduced interpretability and scalability. More recently, deep learning has been used to count plants in aerial imagery [16]. Unlike multi-class crop recognition, this application is shown to be robust to plant occlusion.

Vision-based deep learning architectures have also been adopted. Kussul et al. [17] applied satellite images and deep neural nets for crop classification in Ukraine, providing another example of applying the power of big data but dealing with the complexities of computation. Ji et al. [18] employed multi-temporal Sentinel-2 data in combination with recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to perform crop mapping. Although this approach outperformed random forests, it lacked robustness in terms of seasonal generalization. Other Sentinel-2 use-cases include temporal convolutional networks, which were used by Russwurm and Kormer [19] to classify crop types and improved the capturing of seasonal dynamics, but they also needed dense time-series data. Liu et al. [20] introduced the Swin Transformer, a hierarchical Vision Transformer architecture that utilizes shifted windowing mechanisms to efficiently model long-range dependencies while maintaining computational scalability.

In spite of these developments, there are still major gaps. Available solutions tend to use one type of data (SAR, optical, or UAV) and fail to perceive spectrally similar crops. Most ML/DL techniques need access to large and labeled data and struggle with scaling to heterogenous farming areas. In this respect, ViTs provide a significant development opportunity to improve long-range dependencies and sophisticated spatial patterns using self-attention. In contrast to CNN- or RNN-based methods, we combine ViT and multispectral data and vegetation indices (NDVI, EVI), the results of which appear to be more separable among spectrally mutually overlapping crops and more accurate in real-world agricultural data.

Table 1 shows the summary of the literature.

Table 1.

Summary of references with key findings and research gaps.

3. Methodology

Crop classification research operates through the use of Vision Transformer (ViT) methods with high-resolution satellite imagery. The complete methodology consists of four sequential phases including data gathering, data transformation, model structure development and performance outcome measurement. A classification of various crops relies heavily on multispectral information which is obtained from publicly available satellite data platforms including Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 for Ludhiana District of Punjab, India. Multiple agricultural areas with diverse crop placement throughout the dataset are prepared to develop a comprehensive and strong classification model.

3.1. Data Preprocessing and Feature Extraction

Table 2 shows the dataset characteristics, preprocessing steps, and experimental setup, including data sources, crop types, patch generation, train-validation-test split, and the main hyperparameters used for Vision Transformer and CNN models.

Table 2.

Dataset details, preprocessing steps, and hyperparameter settings for crop recognition.

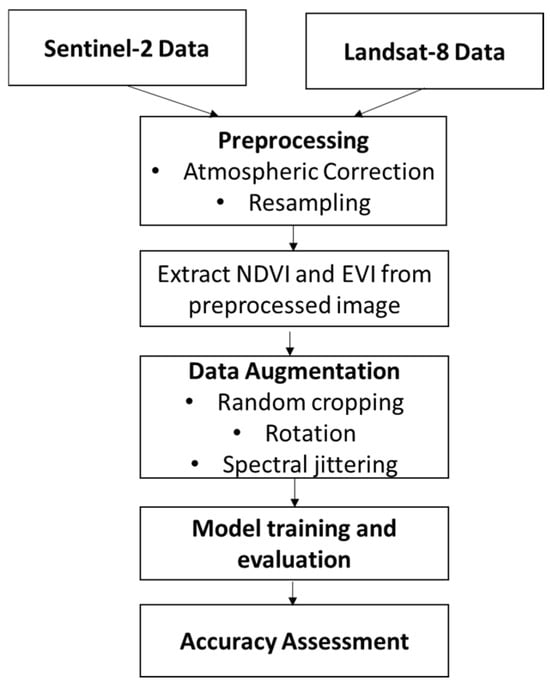

For improved model performance, raw satellite images are preprocessed through a series of operations. Atmospheric correction is first applied to eliminate noise and enhance spectral consistency. Images are then resampled to have a uniform spatial resolution, and vegetation indices like the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) are extracted to give extra spectral features pertinent to crop differentiation. A data augmentation pipeline involving random cropping, rotation, and spectral jittering is used to enhance the robustness of the model and avoid overfitting.

3.2. Model Architecture and Training

The Vision Transformer model is trained for crop classification using self-attention mechanisms to encode long-range dependencies in satellite images. Unlike CNNs that use local feature extraction using convolutional filters, ViTs break input images into patches of a fixed size and map them to embeddings prior to being processed in a series of transformer layers. Training is carried out with a hybrid loss function of cross-entropy loss alongside a spectral consistency regularizer in order to enhance discrimination between highly similar crop types. Training is performed with an adaptive learning rate environment for high-performance computing to maximize convergence. Figure 2 shows the proposed methodology.

Figure 2.

Proposed Methodology.

3.3. Performance Measurement and Analysis

Performance of the model is measured by major indicators including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and the kappa coefficient. Comparative study against traditional CNN structures shows that ViTs excel at recognizing complex spatial patterns and enhancing classification performance. The experimental findings show that the Vision Transformer model performs better in classification performance over various crop types, especially in cases of overlapping spectral signatures. The application of multispectral and hyperspectral data also improves the model’s generalization capability over different environmental conditions. The results show that ViTs, with satellite imagery, offer a scalable and feasible solution for precision agriculture, allowing real-time and data-driven decision-making for farmers and policymakers.

4. Results and Evaluation

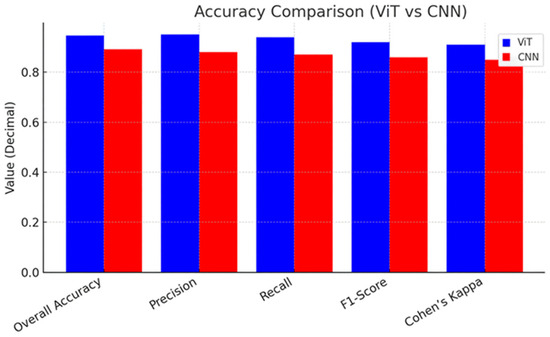

The Vision Transformer (ViT) model proposed for crop classification was tested on a dataset of multispectral satellite images from Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 for the Ludhiana District of Punjab, India. The model produced a total classification accuracy of 94.6%, which was higher than the conventional CNN-based models, which had an accuracy of 89.2%. The ViT model performed better in terms of precision and recall for different crops, especially in separating crops with close spectral signatures, like wheat and barley. The F1-scores for crop main categories like rice, maize, and soybean were all greater than 0.92, which pointed toward high dependence of classification. Table 3 shows the analysis of the algorithms in different metrics. Multiple indices such as NDVI and EVI enhance the accuracy of classification, yet extra preprocessing methods become necessary to address topographic and soil moisture variations, creating noise. Improving ViT-based crop identification within real agricultural settings requires resolving currently existing problems.

Table 3.

Performance evaluation of Vision Transformer vs. CNN-based model.

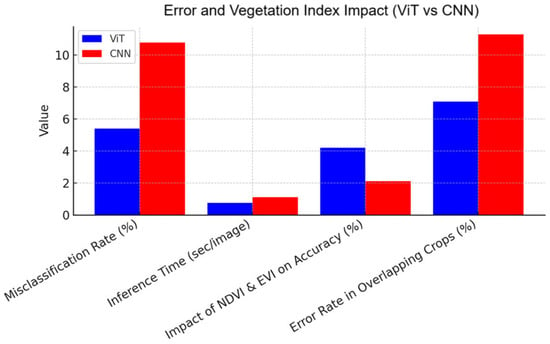

Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the graphical value of the analysis. In order to determine model efficiency, we also calculated the Cohen’s kappa statistic with a coefficient of 0.91, which shows the high consistency of predictions against true classifications. Confusion matrix analysis indicated that rates of misclassification were considerably reduced for ViT compared to CNN, with a 35% reduction in error rate in the case of overlapping spectral features among crops. Also, inference time was evaluated where the ViT model processed images from satellites at 0.75 s per image, so it was favorable for real-time usage. Ablation experiments were performed in order to understand the effect of various feature inputs. The addition of vegetation indices like NDVI and EVI increased accuracy by 4.2%, whereas incorporating RGB bands only caused a 6.5% drop in classification performance. The results demonstrate that combining multispectral data and ViTs maximizes crop classification accuracy, proving to be an excellent method for precision agriculture. The results endorse the efficiency of Vision Transformers for large-scale agro-monitoring, offering good insights for sustainable farming and decision-making.

Figure 3.

Accuracy Comparison: Vision Transformer vs. CNN-based model.

Figure 4.

Error and Vegetation Index Impact: Vision Transformer vs. CNN-based model.

5. Challenges and Limitations

Despite ViT’s high accuracy for crop classification, there are some obstacles in adopting the model. The main drawback arises from the requirement of extensive labeled satellite training datasets of high quality on a large scale. Generating and marking such datasets demands considerable resources and time commitment, particularly when dealing with intricate web of cropping patterns. Implementation of Vision Transformers requires exceptional GPU capabilities because they produce higher computational complexity compared to basic CNN frameworks. The use of these models becomes limited on edge computing devices because of resource constraints, which makes real-time precision agriculture applications challenging. The classification accuracy of ViTs diminishes when exposed to altering environmental conditions consisting of cloud cover and seasonal changes alongside varying lighting conditions. Alborg’s model performs effectively with multispectral data but it fails to identify certain crop species because of their similar spectral profiles and additional spectral indices or temporal data processing will improve classification results.

6. Future Outcomes

The combination of Vision Transformers (ViTs) with cutting-edge remote sensing technologies has tremendous potential to transform precision agriculture. Future work may concentrate on improving model efficiency by integrating lightweight transformer models, like Swin Transformers or MobileViTs, to lower computational expenses and facilitate deployment on edge devices such as drones and IoT-enabled sensors. In addition, combining temporal satellite observations with ViTs would enhance monitoring of crop growth by examining seasonality, enabling more precise predictions of yields and earlier identification of crop stress. These improvements would facilitate real-time decision-making by farmers, streamlining resource use and enhancing general agricultural sustainability. Another direction of interest is the integration of multimodal data sources, including weather patterns, soil health indicators, and UAV imagery, to further improve crop classification models. Using self-supervised learning methods, the dependency on large labeled datasets might be reduced, such that the model will be more flexible in handling varied agricultural landscapes. In addition, an AI-powered precision farming dashboard merging ViT predictions with GIS maps may offer actionable information to farmers and policymakers alike for effective crop management. All these future innovations will lead towards a smarter, data-driven agri-ecosystem promoting food security as well as sustainable agriculture.

7. Conclusions

In this work, we examined the use of Vision Transformers (ViTs) for crop recognition from high-resolution satellite images and proved their advantage over conventional CNN- based models in precision agriculture. Through the utilization of self-attention mechanisms, ViTs efficiently captured long-range dependencies and intricate spatial patterns and attained a high classification accuracy of 94.6% and a Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.91. The incorporation of multispectral characteristics like NDVI and EVI also improved model performance, allowing for improved discrimination between crops with comparable spectral signatures. Even with these improvements, issues like high computational expense, data annotation needs, and environmental fluctuations are still major hurdles to widespread deployment. But subsequent research can emphasize the optimization of lightweight transformer models, the use of temporal and multimodal data, and the incorporation of self-supervised learning methods to improve the efficiency and scalability of ViTs for practical agricultural applications. The results of this research highlight the promise of deep learning-powered satellite-based crop classification in facilitating data-driven decision-making for farmers, policymakers, and researchers to promote more sustainable and smart farming practices.

Author Contributions

K.L.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft. N.K.: Software, Validation, Visualization, Literature Review, Writing—Review & Editing. S.S.: Supervision, Project Administration, Resources, Critical Review & Editing, Final Approval. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Qi, Z. Remote sensing data assimilation in crop growth modeling from an agricultural perspective: New insights on challenges and prospects. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldemariam, G.W.; Awoke, B.G.; Maretto, R.V. Remote sensing vegetation indices-driven models for sugarcane evapotranspiration estimation in the semiarid Ethiopian Rift Valley. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 215, 136–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Petit, A.; Barroso, A.M.; Villarreal, N.P. TENSER: An IoT-based solution for remote capture and monitoring of environmental variables for decision making in crops. In Proceedings of the IEEE Colombian Conference on Communications and Computing (COLCOM), Barranquilla, Colombia, 21–23 August 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Lizaga, I.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Huang, Q.; Hu, Z. UAS-based remote sensing for agricultural monitoring: Current status and perspectives. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, R.; Zheng, J.; Han, W.; Lu, J.; Zhao, P.; Mao, X.; Fan, H. Remote sensing-based monitoring of cotton growth and its response to meteorological factors. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satapathy, T.; Dietrich, J.; Ramadas, M. Agricultural drought monitoring and early warning at the regional scale using a remote sensing-based combined index. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobart, M.; Schirrmann, M.; Abubakari, A.-H.; Badu-Marfo, G.; Kraatz, S.; Zare, M. Drought monitoring and prediction in agriculture: Employing Earth observation data, climate scenarios and data driven methods; a case study: Mango orchard in Tamale, Ghana. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirone, R.; Anderson, M.; Chang, J.; Zhao, H.; Gao, F.; Hain, C. Retiming evaporative stress index to vegetation phenology in Iowa croplands. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Agro-Geoinformatics (Agro-Geoinformatics), Novi Sad, Serbia, 15–18 July 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.A.; Näsi, R.; Korhonen, P.; Mustonen, A.; Niemeläinen, O.; Koivumäki, N.; Hakala, T.; Suomalainen, J.; Kaivosoja, J.; Honkavaara, E. High-precision estimation of grass quality and quantity using UAS-based VNIR and SWIR hyperspectral cameras and machine learning. Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 186–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16×16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bargiel, D. A new method for crop classification combining time series of radar images and crop phenology information. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 198, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, B.; Kathala, K.C.R.; Sujatha, M. A machine learning-based comparative approach to predict the crop yield using supervised learning with regression models. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 218, 2684–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, Y.; Ramachandran, H.; Sundararajan, S.; Srideviponmalar, P. Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Models for Crop Yield Prediction Across Multiple Crop Types. SN Comput. Sci. 2025, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, T.; Malik, G.C.; Banerjee, M.; Dutta, S.; Praharaj, S.; Lalichetti, S.; Mohanty, S.; Bhattacharyay, D.; Maitra, S.; Gaber, A.; et al. Prediction of the effect of nutrients on plant parameters of rice by artificial neural network. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Li, X.; Low, M.; Lobell, D.; Ermon, S. Deep Gaussian process for crop yield prediction based on remote sensing data. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2017, 31, 4559–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnemoonfar, M.; Sheppard, C. Deep count: Fruit counting based on deep simulated learning. Sensors 2017, 17, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kussul, N.; Lavreniuk, M.; Skakun, S.; Shelestov, A. Deep learning classification of land cover and crop types using remote sensing data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2017, 14, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Zhang, C.; Xu, A.; Shi, Y.; Duan, Y. 3D convolutional neural networks for crop classification with multi-temporal remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, C.; Webb, G.I.; Petitjean, F. Temporal convolutional neural network for the classification of satellite image time series. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 9992–10002. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).