Abstract

In this study, a PVA/graphene oxide (GO) hydrogel nanocomposite was synthesized as a adsorbent for Li+ removal from aqueous solutions. The composite was characterized by FTIR, XRD, and SEM/EDS to verify interfacial interactions and porous morphology. Batch adsorption experiments were performed to evaluate the effects of contact time, initial concentration, pH, and temperature. Kinetic analysis indicated that the pseudo-first-order model provided a better fit than the pseudo-second-order model under the tested conditions. Equilibrium data were best described by the Freundlich isotherm, suggesting adsorption on a heterogeneous surface. Thermodynamic results (ΔG° < 0) confirmed a spontaneous process, while the observed decrease in capacity with increasing temperature indicated an exothermic adsorption behavior. Overall, the PVA/GO hydrogel nanocomposite shows promise for lithium recovery from dilute aqueous streams.

1. Introduction

The rapid growth of rechargeable batteries for electric vehicles and grid-scale storage continues to intensify the demand for lithium and to push materials and processes across the battery value chain to new limits [1,2,3,4]. While much of the literature focuses on cell and interface innovation, ranging from interface engineering in Li-ion systems to the fast-charging behavior and in-operando diagnostics of solid-state batteries [1,2,3], the upstream challenge of securing lithium in efficient, sustainable ways remains central. Environmental and water-resource concerns in sensitive regions underscore the need for recovery routes that reduce land, water, and carbon footprints [5]. In parallel, process-intensified pathways for lithium recovery have advanced, including electrochemical methods and membrane-based separations aimed at handling dilute, multi-ion aqueous matrices typical of brines and leachates while improving scalability and operability [6,7].

Alongside process innovations, materials-assisted uptake using nanostructured carbons and hybrid frameworks has drawn increasing attention for aqueous systems. High-surface-area graphenic architectures provide tunable chemistry and robust form factors relevant to sorption and process integration [8,9]. Beyond carbon, hybrid adsorbents—such as metal-oxide/graphene composites and porous oxide systems—offer complementary routes to engineer transport and interfacial phenomena for water-borne species management in complex matrices [10,11].

Building on these developments, the present study synthesizes and characterizes a PVA/GO hydrogel nanocomposite and evaluates its lithium uptake behavior in batch systems. Structural and microstructural features are examined via FTIR, XRD, and SEM; the effects of contact time, pH, initial concentration, and temperature are assessed; and standard kinetic and isotherm models are fitted to interpret uptake mechanisms and thermodynamic tendencies. The goal is to provide reproducible materials–process evidence and a clear experimental baseline that connects hydrogel formulation, structure, and aqueous uptake behavior in contexts relevant to emerging lithium recovery schemes.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA, ≥98% hydrolyzed, Mw 85–124 kDa, CAS 9002-89-5), graphene oxide (GO) aqueous dispersion (1 mg mL−1) or GO powder, sodium tetraborate decahydrate (borax, CAS 1303-96-4), boric acid (H3BO3, CAS 10043-35-3), glutaraldehyde (25% aq., GA, CAS 111-30-8; optional), hydrochloric acid (HCl), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and lithium chloride (LiCl) were obtained from reputable suppliers (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and used as received unless otherwise stated. Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm) was used throughout.

2.2. Synthesis of Graphene Oxide

Graphite powder (1.0 g) was dispersed in concentrated H2SO4 (23 mL) in an ice bath (<20 °C) under stirring for 10 min. KMnO4 (3.0 g) was added slowly (10–15 min), keeping the temperature below 20 °C, and the slurry was stirred at 35–40 °C for 30–60 min. The mixture was diluted carefully with ice water (200 mL) and quenched with H2O2 (30%, 3 mL) to yield a yellow dispersion. The product was washed by repeated centrifugation/redispersion with water to pH ~6–7 and finally adjusted to 1 mg mL−1 (bath sonication 10–15 min).

2.3. Preparation of PVA/GO Hydrogel

A 10 wt% PVA solution was prepared by dissolving PVA (10.0 g) in water (90.0 g) at 90 °C under stirring (~2 h) until clear, then cooled to ~40 °C. GO stock (1 mg mL−1) was added to the PVA solution to reach 0.2–0.5 wt% GO relative to PVA (typical: 0.3 wt%; e.g., 30 mL GO dispersion for 10 g PVA). The mixture was stirred for 15–20 min and briefly de-foamed.

Hydrogels were formed by dispensing the PVA/GO precursor dropwise into a saturated aqueous boric acid bath (~4–5 wt%) under gentle stirring (~200 rpm). The precursor (10 wt% PVA with 0.3 wt% GO relative to PVA, unless otherwise stated) was loaded into a syringe fitted with a 21–25 G needle held 2–5 cm above the bath; droplets gelled on contact via PVA–borate complexation, producing nearly spherical beads (≈1–4 mm; diameter governed by needle gauge and flow rate). Beads were allowed to cure for 30–60 min, collected by sieving, rinsed with deionized water 3–5× until near-neutral pH and stable conductivity, and stored hydrated at 4 °C. Where noted, a single freeze–thaw step (−20 °C, 12 h, 25 °C, 12 h) was applied to enhance mechanical integrity; representative beads were lyophilized to determine the dry/wet mass ratio for subsequent uptake calculations.

2.4. Analytical Calibration (Flame AAS)

Lithium was quantified by flame atomic absorption spectroscopy at 670.8 nm (instrument model, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). A 1000 mg L−1 Li+ stock solution (LiCl in 1% v/v HNO3) was diluted to a 100 mg L−1 intermediate and then to working standards of 1–40 mg L−1. Standards and unknowns were measured in triplicate, and a linear calibration curve was used to determine equilibrium concentrations (C_e).

2.5. Adsorption Studies

- Effect of pH:

Batch adsorption experiments (m = 25 mg adsorbent, V = 25 mL, C0 = 25 mg L−1, 25 °C) showed a pronounced pH dependence. The highest uptake was observed at pH 6 (q_e ≈ 20.2 mg g−1; 86.3% removal). At lower pH, competition with H+ and protonation of oxygen-containing surface groups reduced Li+ uptake. At pH > 7, the apparent removal decreased, which may be associated with changes in the hydrogel network (e.g., borate crosslink stability/swelling) and/or increased background electrolyte effects during pH adjustment. Therefore, pH 6 was selected for subsequent experiments.

- Effect of Adsorbent Dose:

At fixed C0 = 25 mg L−1 and V = 25 mL (pH 6, 25 °C), increasing the adsorbent dose from 10 to 35 mg increased removal from ~43% to ~91%, while the equilibrium capacity decreased from ~26.9 to ~16.3 mg g−1. The decrease in qe is attributed to a lower solute-to-sorbent ratio and partial underutilization of adsorption sites at higher dosages.

- Effect of Initial Concentration:

Using m = 25 mg and V = 25 mL at pH 6 (25 °C), increasing C0 from 10 to 35 mg L−1 increased qe (e.g., from 8.5 to 20.5 mg g−1), whereas the removal percentage slightly decreased at higher C0.

- Equilibrium Isotherms:

Nonlinear regression at 25 °C showed that the Freundlich isotherm provided the best fit (R2 = 0.99; KF = 11.65; 1/n = 0.66). In contrast, the Langmuir model produced non-physical parameters (e.g., negative KL) and was therefore not considered for further interpretation.

- Temperature Dependence and Thermodynamics:

At C0 = 35 mg L−1, m = 25 mg, and pH = 6, increasing temperature from 25 to 65 °C decreased qe from 21.5 to 18.2 mg g−1 and reduced Kc, consistent with an exothermic adsorption process. van’t Hoff analysis yielded ΔH° = −11.51 kJ mol−1 and ΔS° = −28.40 J mol−1 K−1; ΔG° remained negative over the investigated temperature range.

- Kinetics:

Time-dependent experiments (C0 = 25 mg L−1, m = 250 mg, V = 250 mL, pH 6, 25 °C) showed rapid initial uptake (qt ≈ 11 mg g−1 at ~100 min), approaching qt ≈ 20 mg g−1 after 600–720 min. Nonlinear fitting favored the pseudo-first-order model (R2 = 0.91) over pseudo-second-order (R2 = 0.85), while the Elovich (R2 = 0.79) and intraparticle diffusion (R2 = 0.64) models showed poorer agreement. Overall, the profiles suggest fast surface adsorption followed by a slower intraparticle transport step. The slight late-time decline in removal (~60% at 720 min) may indicate desorption or adsorbent/complex instability and should be examined via additional stability/reproducibility tests.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Adsorption Results

The adsorption results revealed that the process was highly sensitive to pH, adsorbent dosage, initial concentration, temperature, and contact time. Solution pH had a pronounced effect on adsorption efficiency, with maximum uptake observed at pH 6. At lower pH values, protonation of surface functional groups can reduce the availability of binding sites and increase competition with H+, thereby inhibiting uptake. In contrast, at pH > 7 the apparent removal decreased, which may be associated with changes in the hydrogel network (e.g., borate crosslink stability/swelling) and/or increased background electrolyte effects during pH adjustment. Hence, pH 6 was identified as the optimal condition, providing a balance between surface charge conditions and adsorbate stability in solution.

The effect of adsorbent dosage showed that increasing the adsorbent mass from 10 to 35 mg significantly improved removal efficiency from ~43% to ~91%, consistent with the larger number of available adsorption sites. However, the equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe) decreased from ~26.9 to ~16.3 mg g−1 with increasing dosage, reflecting the lower solute-to-sorbent ratio and partial underutilization of adsorption sites at higher dosages (and potentially site overlap/aggregation effects), despite the higher overall removal.

Varying the initial concentration from 10 to 35 mg L−1 increased qe (e.g., from ~8.5 to 20.5 mg g−1), which can be explained by the stronger concentration gradient providing a greater driving force for mass transfer from the bulk solution to the adsorbent surface. However, the percentage removal slightly decreased at higher concentrations, likely due to progressive saturation of available adsorption sites. These results indicate that higher initial concentrations favor adsorption capacity, while reducing removal efficiency under fixed adsorbent loading.

Equilibrium isotherm modeling demonstrated that the Freundlich model provided the best fit (R2 = 0.99), suggesting heterogeneous surface adsorption and possible multilayer formation. The Freundlich constants (K_F = 11.65, 1/n = 0.66) indicated favorable adsorption (1/n < 1), consistent with strong adsorbate–adsorbent interactions. In contrast, the Langmuir model yielded negative constants, implying that ideal monolayer adsorption on a homogeneous surface was not an appropriate description for this system under the tested conditions.

Temperature-dependent experiments revealed that increasing the temperature from 25 to 65 °C led to a decrease in qe (from 21.5 to 18.2 mg g−1), supporting an exothermic adsorption process. Reduced adsorption at elevated temperatures may be associated with weakening of physical interactions and enhanced desorption. Thermodynamic parameters derived from the van’t Hoff plot showed that ΔH° = −11.51 kJ mol−1 and ΔS° = −28.40 J mol−1 K−1, while ΔG° values were negative throughout the studied temperature range, indicating a spontaneous and energetically favorable yet entropy-decreasing process, consistent with a more ordered adsorbate arrangement on the adsorbent during uptake.

Kinetic analysis indicated a rapid initial adsorption phase due to abundant vacant surface sites, followed by a slower phase where intraparticle diffusion and/or network transport limitations became more important. The pseudo-first-order kinetic model (R2 = 0.91) fitted the data better than the pseudo-second-order model (R2 = 0.85), suggesting that the overall rate was predominantly governed by surface interactions rather than purely chemisorption-controlled uptake. The poorer fits of the Elovich (R2 = 0.79) and intraparticle diffusion (R2 = 0.64) models indicate that although diffusion contributes to the overall process, it is not the sole rate-controlling mechanism. A slight late-time decline in removal (e.g., ~60% at 720 min) may reflect partial desorption or adsorbent/complex instability under prolonged equilibration and should be verified through replicate runs and post-adsorption stability assessments.

Overall, the results demonstrate that adsorption is spontaneous and exothermic and is strongly influenced by pH and dosage. The mechanism likely involves fast surface adsorption followed by a slower transport-controlled step, with electrostatic attraction and physical adsorption playing key roles.

3.2. FTIR–XRD–SEM Results

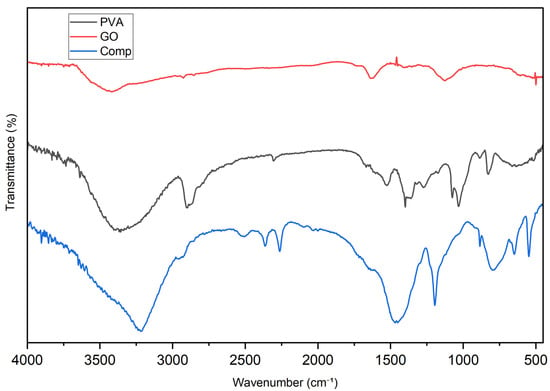

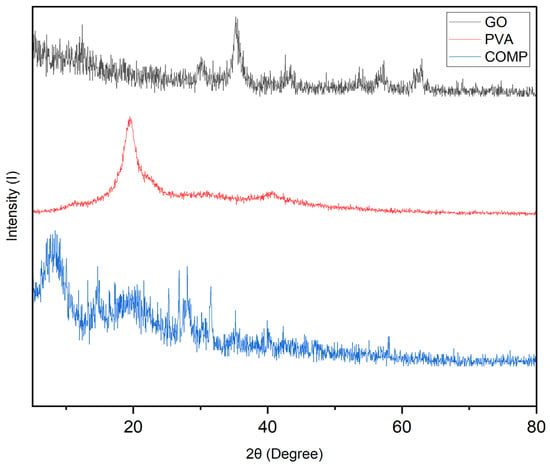

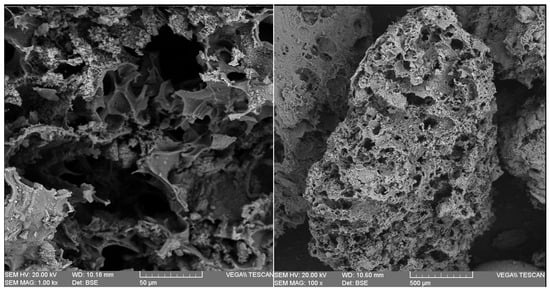

FTIR spectra confirmed successful interfacial interactions between PVA and GO in the composite (Figure 1). Compared with the neat components, the composite showed a broadened O–H stretching band around 3400–3200 cm−1 with a slight shift to lower wavenumbers, together with attenuated C=O (~1720 cm−1) and C–O/C–O–C bands (~1220 and ~1050 cm−1), indicating hydrogen bonding and bonding/anchoring of oxygenated groups at the PVA–GO interface. XRD patterns further supported this structure (Figure 2): the characteristic (001) reflection of GO at ~2θ = 10–11° was markedly weakened or vanished in the composite, while the semicrystalline PVA halo at ~19–20° became broader and less intense, indicating exfoliation/intercalation of GO sheets within the PVA matrix and a reduction in PVA crystallinity upon network formation. SEM micrographs revealed the expected morphological evolution from relatively smooth PVA and wrinkled, sheet-like GO to a well-interconnected micro/mesoporous composite network (Figure 3), in which GO platelets were uniformly dispersed across the polymer matrix; EDS maps (C, O) corroborated the homogeneous distribution of the carbonaceous phase. Collectively, these features point to strong interfacial coupling, improved dispersion of GO, and a porous architecture favorable for Li+ adsorption and transport.

Figure 1.

FT−IR spectra of GO, PVA, and Composite.

Figure 2.

XRD pattern of GO, PVA, and Composite.

Figure 3.

FE-SEM images of final Composite.

4. Conclusions

A PVA/GO hydrogel nanocomposite was successfully fabricated, showing strong interfacial interactions (FTIR), reduced GO stacking and altered PVA crystallinity (XRD), and a porous interconnected morphology (SEM/EDS), which together favor Li+ uptake and transport. Batch adsorption tests showed maximum uptake around pH 6 and a strong dependence on dose and initial concentration. Kinetic modeling suggested that the pseudo-first-order model described the uptake behavior better than the pseudo-second-order model under the studied conditions. Equilibrium data were best fitted by the Freundlich isotherm, indicating adsorption on a heterogeneous surface. Thermodynamic analysis indicated a spontaneous process (ΔG° < 0) and an exothermic tendency, consistent with the observed decrease in qe at higher temperatures. These results support the potential of the composite as a sorbent for Li+ removal/recovery from aqueous matrices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.H. and M.G.D.; methodology, A.A.H. and S.H.B.; investigation, A.A.H.; formal analysis, A.A.H. and S.H.B.; data curation, A.A.H.; writing—original draft, A.A.H.; writing—review and editing, S.H.B. and M.G.D.; supervision, M.G.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Council of Iran University of Science and Technology (IUST), Tehran, Iran, grant number 160/22061.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the laboratories and analytical facilities at Iran University of Science and Technology (IUST), Tehran, Iran.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bouguern, M.D.; MR, A.K.; Zaghib, K. The critical role of interfaces in advanced Li-ion battery technology: A comprehensive review. J. Power Sources 2024, 623, 235457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, R.; Nelson, T.; Nguyen, T.V.; Nelson, C.; Antony, H.; Abaoag, B.; Ozkan, M.; Ozkan, C.S. A Comprehensive Review of Solid-State Lithium Batteries: Fast Charging Characteristics and In-Operando Diagnostics. Nano Energy 2025, 142, 111232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Hossen, S.; Sarkar, B.; Rahman, M.T.; Lee, S.C.; Jung, Y.; Shim, J.S. High density 3D-structured graphene for long-life and high energy density lithium-ion battery. J. Power Sources 2025, 650, 237493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolawole, M.I.; Ayodele, B.L. A Review of Solid-State Battery for Advancement in Energy Storage. Int. J. Res. Innov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 10, 914–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, M.L.; Torres, W.R.; Galli, C.I.; Chagnes, A.; Flexer, V. Environmental impact of direct lithium extraction from brines. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suu, L.; Lim, J.; Lee, J.-H.; Choi, Y.; Choi, J.-S. Advances in electrochemical recovery of valuable metals: A focus on lithium. Desalination 2025, 612, 118960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, Z.H.; Lienhard, J.H. Emerging membrane technologies for sustainable lithium extraction from brines and leachates: Innovations, challenges, and industrial scalability. Desalination 2025, 598, 118411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-H.; Li, S.-P.; Sun, S.-Y.; Yin, X.-S.; Yu, J.-G. Lithium selective adsorption on 1-D MnO2 nanostructure ion-sieve. Adv. Powder Technol. 2009, 20, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kapoor, D.; Khasnabis, S.; Singh, J.; Ramamurthy, P.C. Mechanism and kinetics of adsorption and removal of heavy metals from wastewater using nanomaterials. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 2351–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Ye, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Cao, C.; Du, J.; Kong, X.; Chen, Z.; Xi, Y. Metal–organic framework-derived porous metal oxide/graphene nanocomposites as effective adsorbents for mitigating ammonia nitrogen inhibition in high concentration anaerobic digestion of rural organic waste. Fuel 2023, 332, 126032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrzynska, K. Preconcentration and removal of Pb (II) ions from aqueous solutions using graphene-based nanomaterials. Materials 2023, 16, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).