Abstract

Lignin, an abundant biopolymer in biomass, represents significant potential for environmental applications, particularly in heavy metal adsorption from contaminated water. In Mexico, maize stover, a major agricultural by-product in the Bajío region, is often underutilized, leading to environmental pollution. This study focuses on optimizing lignin extraction from maize stover to transform this waste into a value-added material, addressing both waste management and water treatment challenges. Lignin was extracted via alkaline hydrolysis using NaOH under varying conditions: NaOH concentration (10–40% m/V), temperature (25–60 °C), and reaction time (3–72 h). Two particle sizes (20 and 100 mesh) were tested, with mechanical agitation or sonication (40 kHz) as energy sources. The extracted lignin was characterized using FTIR spectroscopy to confirm its structural integrity. The highest lignin yield (11%) was achieved using 40% NaOH at 25 °C with sonication for 25 min, matching the theoretical lignin content in maize stover (11.1%). Traditional mechanical agitation at 60 °C for 72 h yielded only 8%. Ultrasonication not only improved efficiency but also reduced the reaction time and energy consumption. The particle size (20 mesh) marginally enhanced yields, though handling larger particles proved more practical. The FTIR analysis confirmed the characteristic lignin functional groups, including aromatic rings and hydroxyl groups. The NaOH solution was successfully recovered for reuse, enhancing the sustainability of the method. Ultrasonication significantly optimizes lignin extraction from maize stover, offering a greener, faster, and more efficient alternative to conventional methods. This approach aligns with circular economy principles by minimizing waste and maximizing resource efficiency.

1. Introduction

Accelerating anthropogenic climate change, driven predominantly by fossil fuel combustion, necessitates an urgent transition towards sustainable energy systems. Devastative impacts of conventional energy resources, including atmospheric CO2 accumulation, global warming trajectories, and associated public health crises underscore the imperative for renewable alternatives. Within this framework, biomass emerges as the pre-eminent bio-based resource for mitigating carbon emissions, owing to this intrinsic role in the biogenic carbon cycle [1].

Biomass is defined as the biodegradable fraction of products, waste, or residues of biological origins derived from agricultural activities, forestry, or any anthropogenic activity. This includes the biodegradable fraction of municipal and industrial waste. Within the Mexican context, maize stover (Zea mays) represents a predominant biomass source, constituting the principal agroindustrial residue. It accounts for approximately 67% of the nation’s total agricultural waste output [2]. The Bajío region of Guanajuato is a significant contributor, ranking among México’s top ten maize-producing areas. Consequently, it generates substantial quantities of associated agricultural residues. Despite the partial utilization of this residue as livestock feed within the region, a substantial fraction remains unprocessed. This untreated residue decomposes or is burned in situ, giving rise to pollution issues affecting soils, watercourses, and atmospheric emissions through the release of contaminants.

In this context, a significant proportion of this biomass and its derivatives are regarded as low-value waste. One strategy to mitigate the environmental impact associated with this residue is the development of novel and environmentally benign methodologies for valorizing the waste generated within a region’s agricultural sector. Lignocellulosic biomass is abundant, available, and renewable and has served since antiquity as an energy source. Modern developments have extended biomass use to biocombustibles, the chemical industry, and advanced materials engineering, with applications ranging from construction to biomedicine and environmental remediation [3]. Agroindustrial residues primarily consist of lignocellulosic biomass, which is structurally a three-dimensional polymer composed of naturally synthesized plant material. A defining characteristic of lignocellulosic material is its role in conferring structural integrity, rigidity, and mechanical support to the plant cell wall. This biomass is itself composed of three key polymeric constituents: cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin.

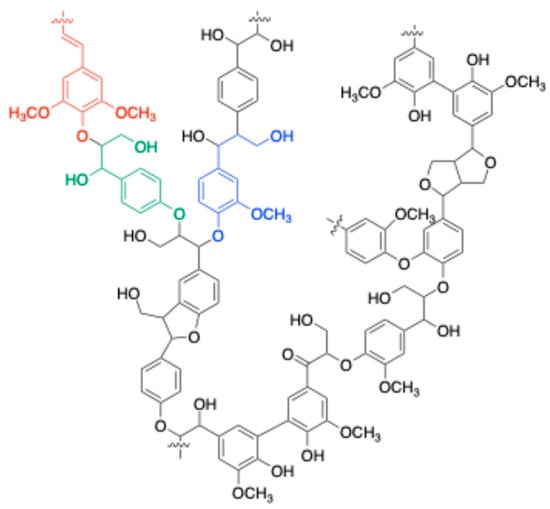

Lignin has attracted particularly extensive and expanding research interest, attributed to its dual significance as the Earth’s second most abundant natural polymer and due to the emergence of novel valorization pathways that position it as a high-value renewable feedstock. This burgeoning focus is fundamentally aligned with sustainability-driven chemistry [4]. Lignin’s structure contains numerous hydroxyl groups, which enable the biosorption of heavy metals and serve as reactive sites for chemical modification, thereby enhancing its chemical properties (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Lignin’s macromolecular framework (sinapyl alcohol—red, guaiacyl alcohol—blue, and p-coumaryl alcohol—green) [5].

This study focused on optimizing lignin extraction. Among various methods reported for lignin extraction, alkaline hydrolysis was selected, given that bases such as hydrogen peroxide, calcium hydroxide, and sodium hydroxide have proven efficient for alkaline lignin extraction [6]. Specifically, NaOH is used in alkaline pretreatments to promote the solubilization and extraction of lignin by disrupting acetyl linkages in hemicellulose and ester linkages between lignin and carbohydrates [7].

2. Methods and Results

2.1. Raw Material Preparation

Maize stover residues were collected from the Bajío region of Guanajuato, México. The biomass was thoroughly washed with distilled water to remove soil and impurities and subsequently dried at 60 °C for 24 h. The dried material was pulverized using a mechanical mill and sieved to obtain two distinct particle sizes: a fine fraction (100 mesh, 0.149 mm) and a coarse fraction (20 mesh, 0.841 mm). The pulverized biomass was stored in a desiccator until use.

2.2. General Lignin Alkaline Extraction with Mechanical Agitation

A mass of 6.0 g of pulverized maize stover (of either 100 or 20 mesh) was placed in a 250 mL round-bottom flask. To this, 100 mL of distilled water was added, and the mixture was hydrated under mechanical stirring (300 rpm) for 30 min at ambient temperature. Subsequently, an amount of NaOH was added to the solution to achieve a final concentration within the range of 10–40% mass/Volume (% m/V). Initially alkaline conditions were established based on the reported literature with different soda concentrations [8].

The reaction mixture was subjected to mechanical agitation for a period ranging from 3 to 72 h. The temperature was controlled and varied between 25 °C and 40 °C using a thermostatically controlled heating mantle. The specific combinations of the NaOH concentration, temperature, and reaction time were studied systematically, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Method Optimization for Standard Lignin Extraction.

Upon the completion of the reaction, the mixture was subjected to gravity filtration to separate the solid residue (cellulose and hemicellulose) from the dark alkaline solution, known as black liquor, which contains the solubilized lignin. The collected black liquor was placed in an ice bath, and dilute H2SO4 [1.0 M] was added dropwise under constant stirring until a pH = 2 was attained [9]. This acidification step induced the precipitation of the lignin from the solution. For the lignin recovery, most of the clear supernatant was decanted. The remaining suspension containing the precipitated lignin was transferred to centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 25 min to pellet the solid. The lignin pellet was dried in an oven at 55 °C for 12 h. The resulting dry lignin was weighed, and the extraction yield was calculated and reported.

2.3. Optimization of Standard Reaction Conditions for Lignin Extraction

The initial phase of this study focused on optimizing the key parameters of alkaline hydrolysis using mechanical agitation: the NaOH concentration, temperature, and reaction time. All experiments start with 6.0 g of biomass. In Experiment 1, employing a low NaOH concentration (10% m/V) at 25 °C for an extended period (72 h) resulted only in trace amounts of lignin. This suggests that the energy barrier for breaking linkages binding lignin to hemicellulose is not surmounted by a diluted alkaline solution at room temperature, even over a prolonged duration. Upon increasing the temperature to 40 °C while maintaining the NaOH concentration at 10% m/V and the reaction time at 72 h in Experiment 2, the lignin yield improves modestly to approximately 3%, indicating that thermal energy enhances the solvolysis efficiency of the alkaline solution. However, increasing the alkali concentration to 40% m/V without a temperature elevation in Experiment 3 yielded a similar lignin amount, indicating that a high alkali concentration alone cannot compensate for the lack of heating. Experiment 4 shows a combined increase in both the NaOH concentration, to 40%, and temperature, to 40 °C, for 72 h produced the highest yield of 8% (≈480 mg of pure lignin), underscoring the synergistic effect of the concentration and temperature in promoting biomass delignification under mechanical stirring. Short reaction times (3 h) at 40% NaOH and either 40 °C or 25 °C (Experiments 5 and 6, respectively) resulted in moderated yield reductions to 4% and 3%, confirming the necessity of a sustained reaction duration for effective lignin extraction in conventional conditions.

Overall, these experiments demonstrate that efficient lignin recovery via mechanical agitation requires an elevated alkali concentration, increased temperature, and extended reaction time to approach but not fully reach the theoretical lignin content (≈11.1%) reported in maize stover [10]. These findings establish a baseline for extraction efficacy and illustrate limitations in conventional hydrolysis methods, motivating the exploration of advanced techniques, such as ultrasound-assisted reactions, which later data suggest significantly enhance yield and process efficiency [11].

2.4. Optimization of Ultrasound Reaction Conditions for Lignin Extraction

Ultrasound-assisted extraction is an advanced technique for the isolation of target compounds from biomass. The process leverages high-frequency acoustic energy to disrupt cellular structures and significantly enhance the efficacy of a chosen solvent system. This extraction process has a fundamental mechanism of solid–liquid extraction from biomass and occurs in two stages: (1) Solvation and swelling—when the solvent initially penetrates the plant tissue, hydrating the matrix and solubilizing the desired chemical constituents. (2) Mass transfer—the dissolved compounds then diffuse across the plant tissue and into the bulk solvent, a process governed by concentration gradients and osmotic pressure [12]. The efficacy of ultrasonic irradiation in intensifying this extraction lies in its multi-faceted physical action attributed to the acoustic cavitation; this phenomenon generates intense localized shear forces and shockwaves in microscopic bubbles within the solvent. These turbulent microenvironments drastically disrupt the biomass, facilitating the release of intracellular materials and accelerating their diffusion into the solvent for enhanced mass transfer. The mechanical effects of the ultrasound reduce the particle size and increase the surface area for interactions. Furthermore, this enhances capillary permeability and solvent access into the plant matrix, overcoming natural hydrophobic barriers. Consequently, ultrasonic irradiation induces a pronounced softening and hydration effect on the rigid plant cell wall, rendering it more pliable. The cumulative mechanical stress from ultrasonic vibration ultimately leads to the physical rupture of cell structures. This synergist breakdown of physical and diffusional barriers results in a marked improvement in extraction yield and kinetics [13].

The comparative analysis of lignin extraction efficiencies under ultrasound irradiation versus conventional mechanical agitation, as summarized in Table 2, elucidated the marked enhancements attributable to sonochemical effects. Both methods employed a consistent alkaline concentration of 40% m/V NaOH; however, the source and nature of the energy input differed significantly in mode, duration, and temperature, providing a robust framework for comparative discussion. The mechanical agitation combined with convection heating at 60 °C for 72 h in Experiment 4 achieved an 8% lignin yield, reflecting the convectional baseline extraction efficiency under optimized alkaline hydrolysis conditions. Notably, when mechanical stirring at ambient temperature was employed for the same duration in Experiment 3, the lignin recovery dropped to 4%, underscoring the vital contribution of thermal energy in facilitating biomass delignification.

Table 2.

Reaction conditions for lignin extraction via ultrasound irradiation vs. mechanical agitation and conventional heating.

The introduction of ultrasound at 40 kHz fundamentally transformed the extraction kinetics and yield outcomes. The ultrasound-assisted extraction performed at 60 °C but for a dramatically reduced total irradiation time of only 25 min in Experiment 7 elevated the yield to 10.5%, surpassing the mechanical baseline despite a reaction time reduction. Furthermore, remarkably comparable yields of approximately 11% were attained when ultrasonication was applied at ambient temperature for 25 min (Experiment 8), matching the ≈11% lignin content reported for maize stover [10]. This indicates that ultrasound compensates for the absence of external heating through localized cavitational microenvironments, inducing intense shear forces, microjets, and shockwaves at the biomass–liquid interface, thereby enhancing solvent penetration, breaking cellular structures, and accelerating mass transfer.

The substantial reduction in the reaction time from multiple hours to minutes, alongside decreased or negligible heating requirements, positions ultrasound-assisted alkaline hydrolysis as a highly attractive, energy-efficient alternative. This synergy between ultrasound and alkali chemistry not only optimizes lignin solubilization but also aligns with green chemistry principles by minimizing the energy consumption and operational duration.

2.5. Lignin Characterization

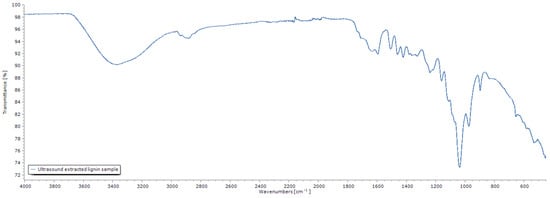

The extracted lignin was characterized by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy (Perkin-Elmer Spectrum Two, Shelton, CT, USA).The FTIR spectrum of the commercial lignin (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and our lignin spectra were compared and were similar. Spectra were analyzed to confirm the presence of key functional groups and structural features indicative of the lignin polymer. On Figure 2, the signals at 3400–3100 cm−1 correspond to O-H stretching of hydroxyl groups and may include absorbed water; 2980–2800 cm−1 bands correspond to C-H stretching vibrations, 1560 cm−1 bands correspond to aromatic ring stretching, and bands near 1000 cm−1 are consistent with ring vibrations overlapping with C-OH and C-O-C stretches [14,15].

Figure 2.

Attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectrum of lignin extracted from maize stover (Spectrum processing using eFTIR [16]).

3. Conclusions

The application of ultrasound significantly accelerates the reaction and enhances lignin solubilization in aqueous phases, leading to yields comparable to those reported in the literature without inducing significant alterations to their structure. This method provides the key advantages of operating at ambient temperatures and greatly reducing reaction times. Overall, ultrasonication use represents a substantial optimization of lignin extraction processes, presenting a more environmentally benign, fast, and efficient alternative to traditional approaches. Furthermore, this technique is consistent with the principles of the circular economy, as it promotes resource efficiency and minimizes waste generation.

Author Contributions

J.J.H.-D., A.C.A.-V., Z.V.B.-R., H.S.M.-H., P.J.R.-V., and P.A.C. contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Dirección de Apoyo a la Investigación y al Posgrado (DAIP), Universidad de Guanajuato.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The research group gratefully acknowledgements the support received for the development of this project and extends its thanks to Dirección de Apoyo a la Investigación y al Posgrado (DAIP), Universidad de Guanajuato for the students’ scholarship; Gilberto Carreño-Aguilera and Saúl Villalobos-Pérez of División de Ingenierías for providing consumables and infrastructure; Alma Hortensia Serafín-Muñoz for their guidance and stimulating discussions and the use of Laboratorio de Ambiental II; the Laboratorio de Evaluación Toxicológica y Riesgos Ambientales (LETRA) led by Gustavo Cruz Jiménez and QFB; Claudia Karina Sánchez from the DCNE for the infrared spectrophotometry; and the developer F. Menges, creator of the software for FTIR data processing “Spectragryph—optical spectroscopy software,” Version 1.2.16.1, 2023, http://www.effemm2.de/spectragryph/, accessed on 20 June 2025. for the free license granted for the use of the Spectragryph software for the processing of infrared spectra.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tursi, A. A Review on Biomass: Importance, Chemistry, Classification, and Conversion. Biofuel Res. J. 2019, 6, 962–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellin, J.; Erenstein, O.; Beuchelt, T.; Camacho, C.; Flores, D. Maize Stover Use and Sustainable Crop Production in Mixed Crop-Livestock Systems in Mexico. Field Crops Res. 2013, 153, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Beltrán, J.U.; Hernández-De Lira, I.O.; Cruz-Santos, M.M.; Saucedo-Luevanos, A.; Hernández-Terán, F.; Balagurusamy, N. Insight into Pretreatment Methods of Lignocellulosic Biomass to Increase Biogas Yield: Current State, Challenges, and Opportunities. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgs, V.; Piili, H.; Gustafsson, J.; Xu, C. A Critical Review on Lignin Structure, Chemistry, and Modification towards Utilisation in Additive Manufacturing of Lignin-Based Composites. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 233, 121416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathna, M.S.; Smith, R.C. Valorization of Lignin as a Sustainable Component of Structural Materials and Composites: Advances from 2011 to 2019. Sustainability 2020, 12, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobato-Peralta, D.R.; Duque-Brito, E.; Villafán-Vidales, H.I.; Longoria, A.; Sebastian, P.J.; Cuentas-Gallegos, A.K.; Arancibia-Bulnes, C.A.; Okoye, P.U. A Review on Trends in Lignin Extraction and Valorization of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Energy Applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Sousa, L.; Chundawat, S.P.; Balan, V.; Dale, B.E. ‘Cradle-to-Grave’ Assessment of Existing Lignocellulose Pretreatment Technologies. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2009, 20, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez Montoya, J.A.; Gordillo Díaz, B.; Vega Atuesta, M.A. Modificación Estructural de La Lignina Extraída a Partir de Carbones de Bajo Rango Para La Obtención de Madera Sintética. Tecnura 2011, 15, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.; Toledano, A.; Serrano, L.; Egüés, I.; González, M.; Marín, F.; Labidi, J. Characterization of Lignins Obtained by Selective Precipitation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2009, 68, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafín Muñoz, A.H.; Molina Guerrero, C.E.; Gutierrez Ortega, N.L.; Leal Vaca, J.C.; Alvarez Vargas, A.; Cano Canchola, C. Characterization and Integrated Process of Pretreatment and Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Corn Straw. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 1857–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Yu, X.; Yagoub, A.E.G.A.; Chen, L.; Zhou, C. Efficient Removal of Lignin from Vegetable Wastes by Ultrasonic and Microwave-Assisted Treatment with Ternary Deep Eutectic Solvent. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 149, 112357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinatoru, M. An Overview of the Ultrasonically Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Principles from Herbs. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2001, 8, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebringerová, A.; Hromádková, Z. An Overview on the Application of Ultrasound in Extraction, Separation and Purification of Plant Polysaccharides. Open Chem. 2010, 8, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoun, K.; Tabib, M.; Salameh, S.J.; Koubaa, M.; Ziegler-Devin, I.; Brosse, N.; Khelfa, A. Isolation and Structural Characterization of Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent Lignin from Brewer’s Spent Grains. Polymers 2024, 16, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeriu, C.G.; Bravo, D.; Gosselink, R.J.A.; van Dam, J.E.G. Characterisation of Structure-Dependent Functional Properties of Lignin with Infrared Spectroscopy. Ind. Crops Prod. 2004, 20, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menges, F. Spectragryph—Optical Spectroscopy Software, Version 1.2.16.1. Available online: https://www.effemm2.de/spectragryph/index.html (accessed on 18 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).