Abstract

Malaria remains a critical global health challenge, particularly affecting Sub-Saharan Africa. Plasmepsins, vital in hydrolyzing peptide bonds within proteins, present promising targets for antimalarial drugs. Plasmepsins I and II, key aspartic proteases, are crucial in various parasite processes. This study investigates the inhibitory properties of quercetin, quercetrin, dihydrostilbene, 4′-methoxy-isoliquiritigenin, and stigmasterol from Globimetula oreophila on plasmepsins through in silico techniques, including ADME predictions and molecular docking. Results reveal strong interactions of these compounds with active site residues, with quercetrin and stigmasterol displaying notable binding affinities. These findings suggest the potential of G. oreophila metabolites as potent plasmepsin inhibitors, offering prospects for malaria treatment and prevention.

1. Introduction

Malaria, caused by the Plasmodium genus, poses a significant threat in tropical and subtropical regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa, including Nigeria [1]. Among the various species, Plasmodium falciparum stands out as the most lethal, leading to severe forms of the disease [2]. The parasite is transmitted through infected Anopheles mosquitoes, resulting in symptoms like fever, anemia, and neurological complications [1,3,4,5]. During the blood stage of malaria, Plasmodium parasites invade red blood cells, feeding on hemoglobin to support their growth and reproduction. Proteases like plasmepsins I and II play crucial roles in hemoglobin breakdown, offering potential targets for antimalarial drug development [3,4,5].

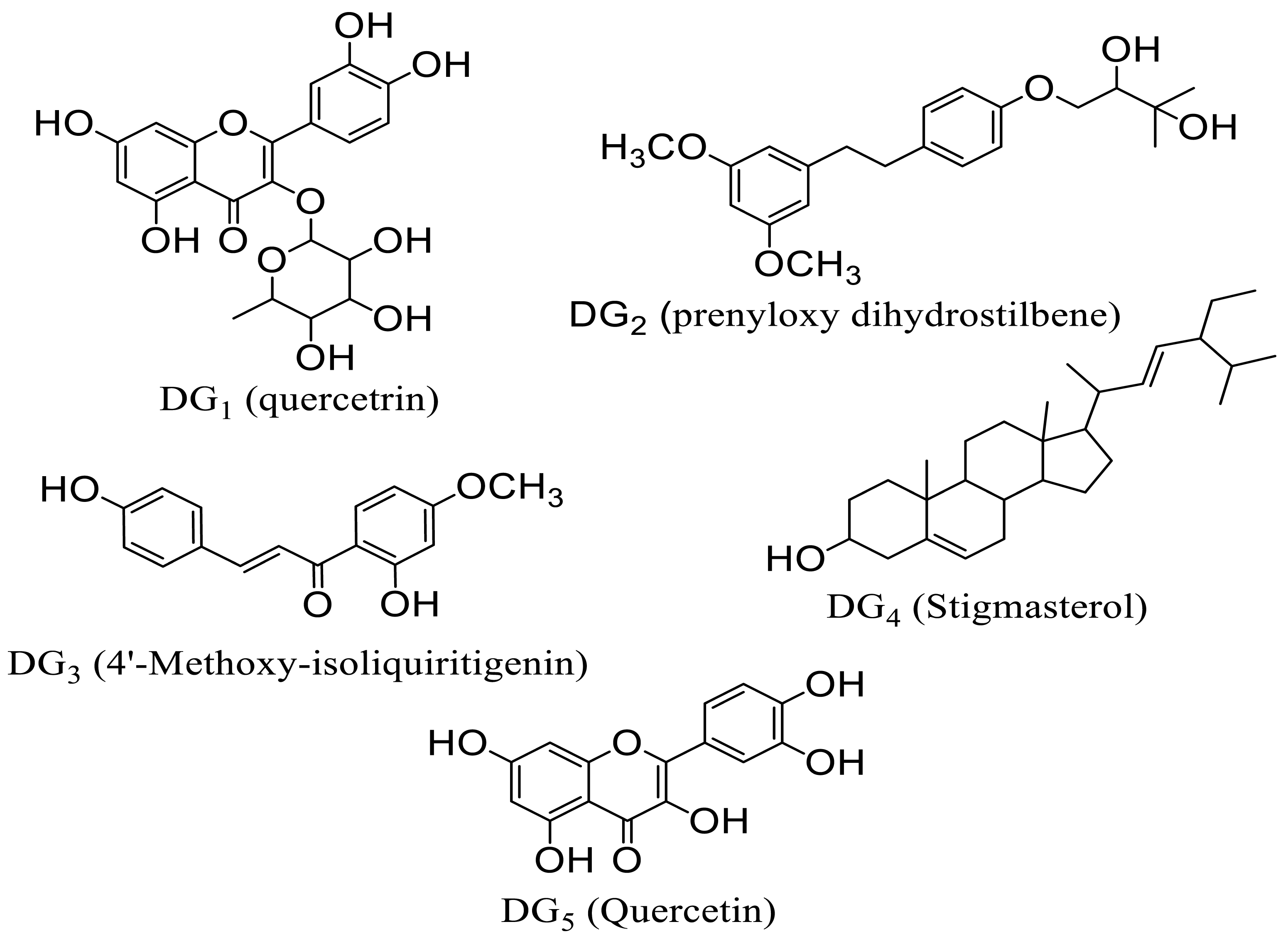

Globimetula oreophila, a member of the mistletoe family, is known for its traditional medicinal uses in treating various ailments [3,6,7]. Phytochemical screenings have revealed a rich array of secondary metabolites in G. oreophila, including alkaloids, flavonoids, triterpenes, and glycosides, some of which exhibit antimalarial activity [3,8,9]. Notably, the plant’s extracts contain essential trace metals like zinc, copper, and iron, further underpinning its therapeutic potential [10]. Previous studies have isolated bioactive compounds from G. oreophila, including stigmasterol, quercetin, quercetrin, dihydrostilbene, and 4′-methoxy-isoliquiritigenin, some of which are novel to the plant genus, demonstrating promise as antimalarial agents [3,11,12].

This study delves into the in silico analysis of secondary metabolites from G. oreophila, focusing on their potential as antimalarial agents targeting Plasmodium falciparum proteases. By investigating the interactions of these compounds with key enzymes involved in the malaria life cycle, such as plasmepsins I and II, the research aims to shed light on novel approaches for combating malaria. Identifying these plant-derived compounds as potential inhibitors of critical malaria-associated proteases suggests a promising avenue for developing effective antimalarial therapies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Software, Hardware, and Databases

AutoDock Vina version 1.5.6, MGL tools [13], UCSF Chimera [14], ChemDraw ultra.12, Discovery Studio, Spartan 04, SwissAdme (online server), Mac OSX, Windows (Intel processor, Corei5).

Protein Crystal Structures

High-resolution, non-mutant crystal structure files of the following enzymes from P. falciparum were obtained from RCSB Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb accessed on 17 November 2023): plasmepsin I [Plm-I; PDB ID: 3QS1] [15], plasmepsin II [Plm-II; PDB ID: 1LF3] [16].

2.2. In Silico Antimalarial Studies

2.2.1. Evaluation of Theoretical Oral Bioavailability

The oral bioavailability of the characterized compounds DG1, DG2, DG3, DG4, and DG5 was predicted theoretically based on Lipinski’s rule of five on the SWISSADME server (http://www.swissadme.ch/index.php accessed on 17 November 2023), and PROTOX-II (https://tox.charite.de/protox3/web accessed on 17 November 2023) servers were used for properties that defined the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) of the test compounds, respectively. Through extensive database utilization, the servers accurately predict various physicochemical properties including lipophilicity, water solubility, pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness, medicinal attributes, and compound toxicity with remarkable precision.

2.2.2. Protein Structure Preparation

As mentioned, the crystal structures were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Before docking, residues were located within 5.0 Å around the native ligands. Chimera UCSF removed all crystallographic water molecules, ions, and bound ligands from the 3D structures retrieved from PDB [14]. The isolated receptors were prepared and saved as rec.pdb. AutoDock Tools [13] were used to edit the rec.pdb files by adding polar hydrogen and Gastegier charges and saving them as pdbqt files.

2.2.3. Ligand Structure Preparation

The 2D structures of the characterized compounds D1-DG5 were generated using ChemDraw ultra.12, and Spartan 04 was used to convert the 2D structures to 3D. Using the AMI semi-empirical method, geometrical optimization was carried out on all the compounds using the Spartan software version 1.1.4, and the optimized structures were stored as mol2 files. AutoDock Tools was used to add hydrogen and Gastegier charges and saved as mol2 files to pdbqt format.

2.2.4. Molecular Docking Analysis

The docking procedure for each protease enzyme was validated before docking the test compounds by separating the co-crystallized ligand from the enzyme crystal structure and re-docking it using the set-up parameters. The procedure that gives conformation superimposable with a geometrical conformation of the co-crystallized ligand in the active site was chosen [17]. Before molecular docking, the active sites were defined according to the coordinates of the crystallographic structures of both enzymes by defining the grid box, and the best pose was obtained, which was used for further studies. The UCSF Chimera was further used for post-docking visualization and pre-MD preparations of all systems (ligands and receptors).

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Theoretical Oral Bioavailability

Table 1 displays the calculated theoretical oral bioavailability metrics of the five isolated compounds, encompassing molecular weight, hydrogen bond donor and acceptor, numbers rotatable bond, and MLogP values. These parameters align with Lipinski’s rule of five for assessing theoretical oral bioavailability [18]. Additionally, the analysis includes the investigation of Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA) and Molar Refractivity (MR) as supplementary pharmacokinetic parameters.

Table 1.

Analysis of theoretical oral bioavailability of isolated compounds based on Lipinski’s rule of five and pharmacokinetic parameters.

3.2. ADMET Profile

Table 2 presents the water solubility values of the isolated compounds, expressed as log Sw, which are in the range of −2.08 to −5.80, indicating good water solubility. Additionally, the cytochrome P450 inhibitory potential of the isolated compounds is explained in the table. Lipophilicity is represented by the consensus log P values, yielding values in the range of 0.16–6.97. The toxicity profile of the test compounds is provided in Table 3.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetics prediction output and oral bioavailability of DG1-DG5 compounds.

Table 3.

Toxicity profile of test compounds.

3.3. Molecular Docking Studies

3.3.1. Grid Box

Based on the grid box parameter, the configuration file (config.txt) was generated. AutoDock Vina produced results in pdbqt format, with the compounds saved in complexes alongside the reference enzymes. The specific grid box parameter is detailed in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

Grid box parameter for enzymes.

3.3.2. Validation of Docking Procedures

The validation of the docking processes conducted on the seven enzymes is demonstrated in Table 5. Each co-crystallized ligand successfully re-docked onto its corresponding protein, aligning well with its original Protein Data Bank (PDB) structures.

Table 5.

Crystal structures of enzyme complexes and re-docked ligands superimposed on crystal structures for validation.

3.3.3. Binding Affinity of Ligands to Protease Enzymes

Table 6 showcases the binding energies of both the co-crystallized ligands and the five isolated compounds in their interactions with the protease enzymes.

Table 6.

The binding energies of the co-crystallized ligands and the five isolated compounds against P. falciparum targets.

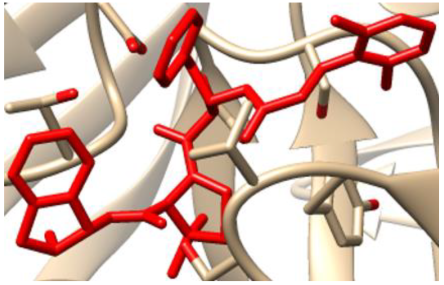

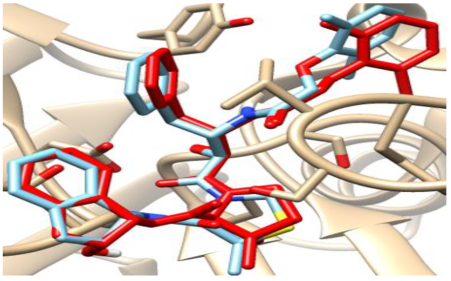

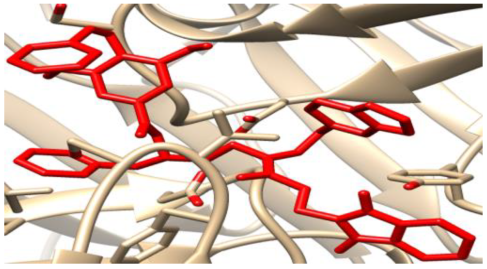

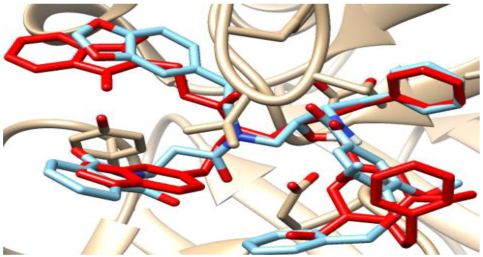

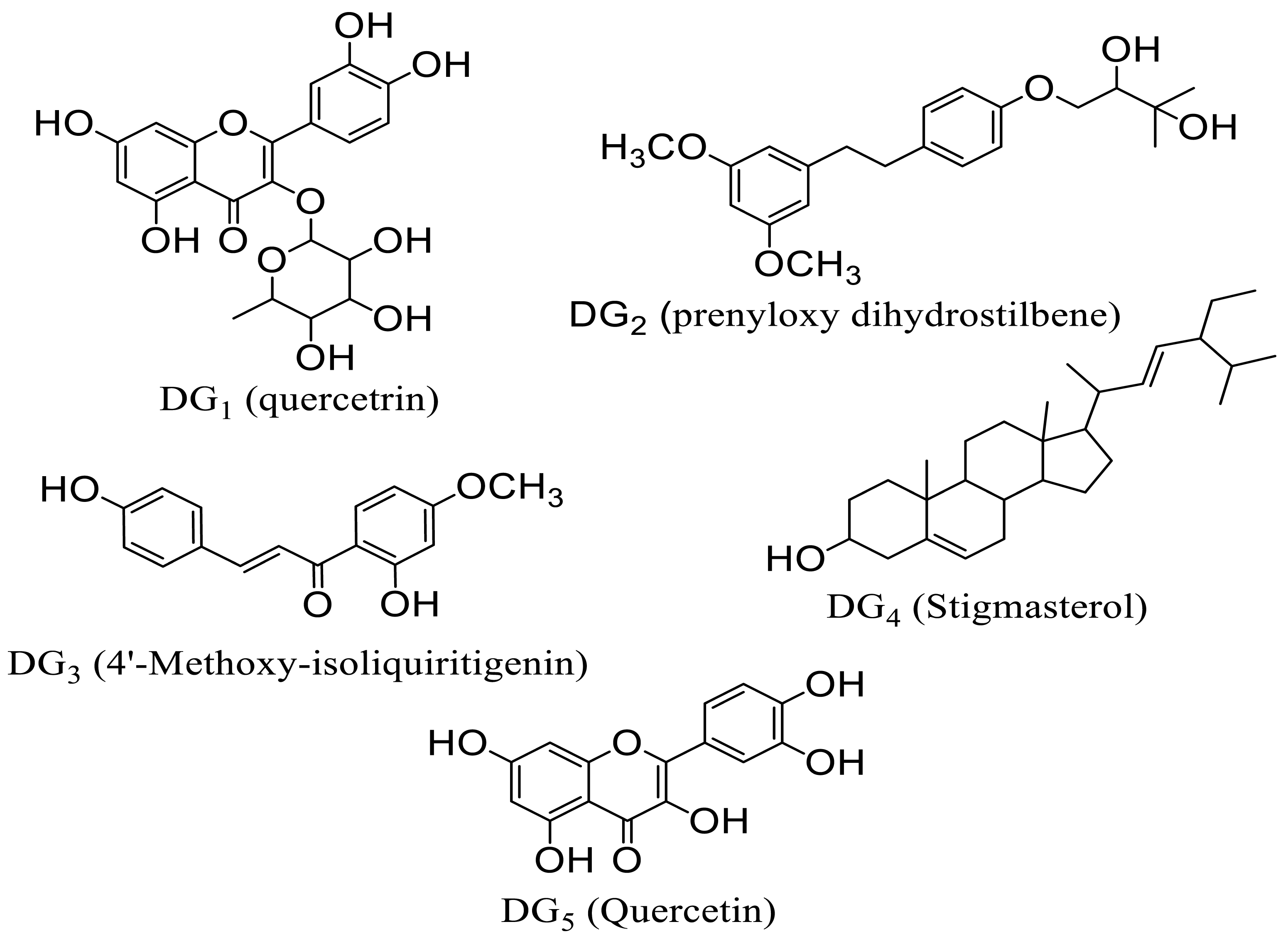

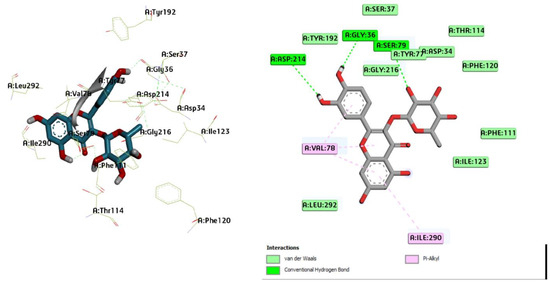

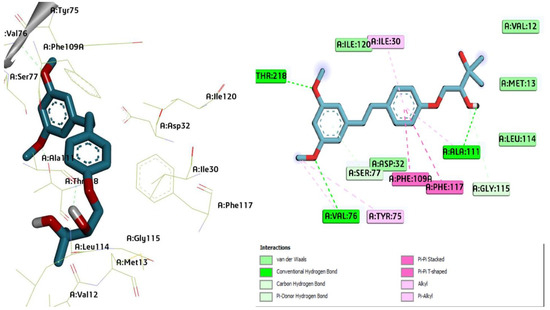

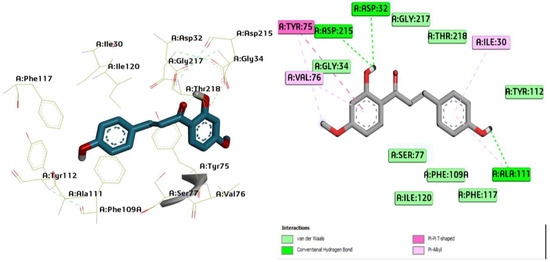

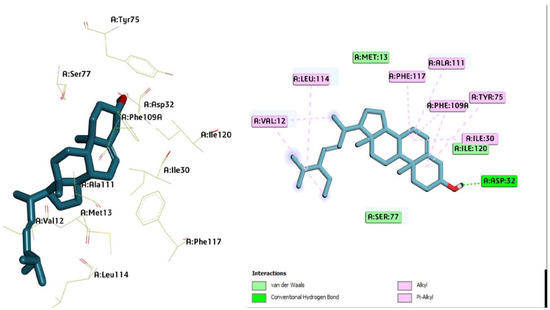

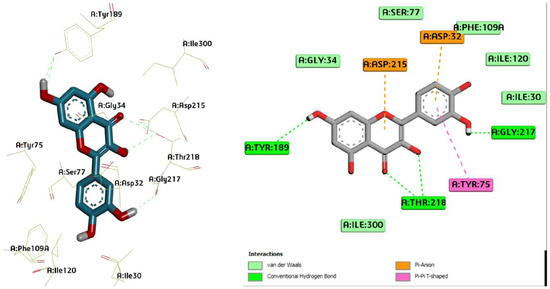

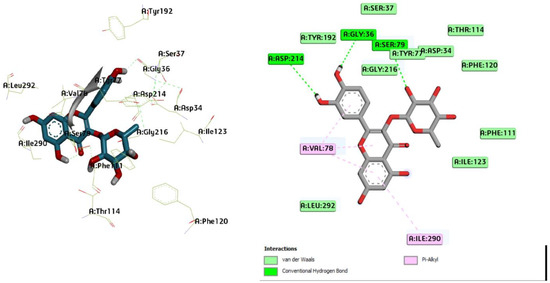

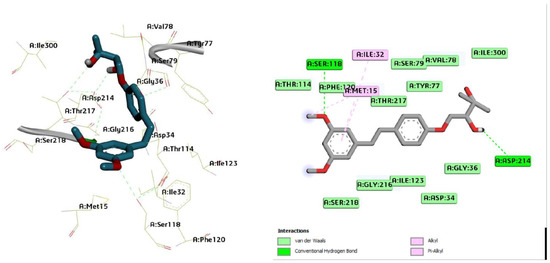

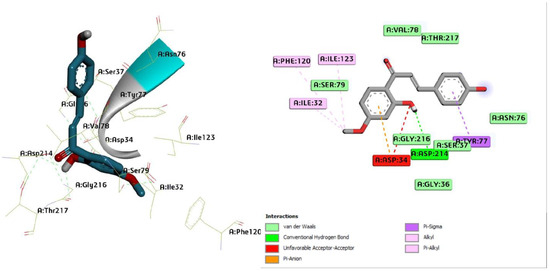

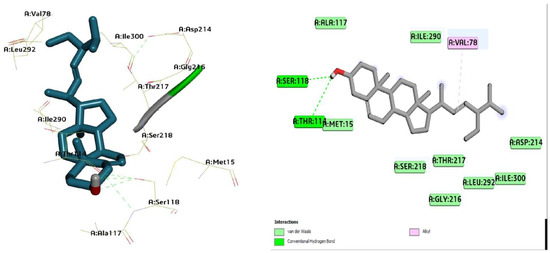

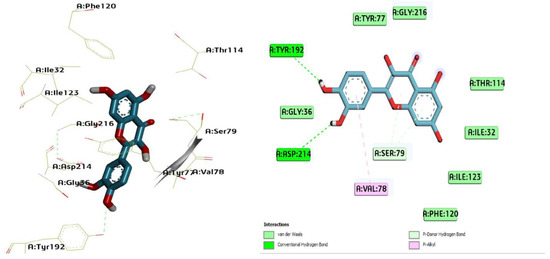

3.3.4. Binding Poses and Binding Interaction Analysis of Isolated Compounds Against Plasmepsin I and II Enzymes

The binding conformation and interaction of the isolated compounds (DG1-DG5) with residues on the active site plasmepsin I and II were studied using chimera [14] and Discovery Studio Suite (www.accelrys.com) Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional molecular pose (left) and 2D (right) interactions of DG1 on binding cavity of plasmepsin I.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional molecular pose (left) and 2D (right) interactions of DG2 on binding cavity of plasmepsin I.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional molecular pose (left) and 2D (right) interactions of DG3 on binding cavity of plasmepsin I.

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional molecular pose (left) and 2D (right) interactions of DG4 on binding cavity of plasmepsin I.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional molecular pose (left) and 2D (right) interactions of DG5 on binding cavity of plasmepsin I.

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional molecular pose (left) and 2D (right) interactions of DG1 on binding cavity of plasmepsin II.

Figure 7.

Three-dimensional molecular pose (left) and 2D (right) interactions of DG2 on binding cavity of plasmepsin II.

Figure 8.

Three-dimensional molecular pose (left) and 2D (right) interactions of DG3 on binding cavity of plasmepsin II.

Figure 9.

Three-dimensional molecular pose (left) and 2D (right) interactions of DG4 on binding cavity of plasmepsin II.

Figure 10.

Three-dimensional molecular pose (left) and 2D (right) interactions of DG5 on binding cavity of plasmepsin II.

3.3.5. Docking Results of Compounds Isolated from Azadirachta Indica with Aspartic Protease Enzymes (Plasmepsin I and II)

The interaction between ligands (quercetrin: DG1; prenyloxy dihydrostilbene: DG2; 4′-methoxy isoliquiritigenin: DG3; stigmasterol: DG4; and quercetin: DG5) and Plm-I (006) and Plm-II (EH58) (which indicated strong interactions leading to high binding affinities) is presented Table 7 and Table 8.

Table 7.

Molecular interactions of amino acid residues of compounds from Azadirachta indica with plasmepsin I (3SQ1).

Table 8.

Molecular interactions of amino acid residues of compounds from Azadirachta indica with plasmepsin II (1LF3).

4. Discussion

The study assessed compounds DG1-DG5 for potential oral absorption, with DG1 showing concerns due to HbA levels exceeding expectations. DG2, DG3, and DG5 displayed high oral absorption potential with low H-bond acceptors, unlike DG1 (Table 1). The compounds had 1–9 rotatable bonds, indicating favorable oral bioavailability, and varied Molar Refractivity (MR), where DG4 hinted at poor oral absorption. Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA) values ranged from 20.23 to 190.28 Å2, with DG2 and DG3 potentially crossing the blood–brain barrier. LogP values (<5) for DG1, DG2, DG3, and DG5 aligned with favorable oral absorption, contrasting DG4 (>5) (Table 1). DG2, DG3, and DG5 exhibited high oral bioavailability and intestinal absorption potential, while DG1 and DG4 showed limitations in these aspects (Table 1).

All compounds except DG2 are non-Pgp substrates, allowing them to access their active sites effectively. DG2’s Pgp substrate status suggests potential difficulty in reaching the target site (Table 2). Moreover, DG2, DG3, and DG4 show CYP inhibitory potential, indicating possible drug–drug interactions, as these isoforms metabolize a significant portion of drugs. Conversely, DG1 does not inhibit any cytochrome P450 isoforms, reducing the likelihood of such interactions (Table 2).

Test compounds are categorized into toxicity classes I-VI based on chemical similarities with toxic compounds and toxic fragment presence, crucial for drug design as shown in Table 3. DG5 emerges as the most toxic with LD50 ≤ 300 mg/kg, while DG2, DG3, and DG4 fall into class IV with LD50 ≤ 2000 mg/kg, and DG1 in class V with LD50 ≤ 5000 mg/kg, suggesting safe administration within dosage limits (Table 3). DG1 and DG5 show potential carcinogenicity but no mutagenic risks or drug-induced hepatotoxicity. Mutagenicity tests reveal DG1, DG3, and DG4 as non-mutagenic, and the compounds show no affinity for pathway-associated biological targets, indicating a lack of target-based adverse effects, as shown in Table 3.

The molecular docking analysis of compound DG1–DG5 (Lig1–Lig5) shows that the binding energies range from −7.2 to −8.6 Kcal/mol while it was −10.7 Kcal/mol for the native ligand (Lig0). The result obtained from the docking analysis demonstrated that the isolated compounds have better docking affinity within the binding pocket of plasmepsin I even though the native ligand (Lig0) had a higher binding energy. DG1 (Lig1) had the highest binding energy of 8.6 Kcal/mol as compared with the other ligands. From Table 6, it was seen that the order of increasing binding energy with the various ligands is −8.6 > −8.0 > −7.5 > −7.2 Kcal/mol (DG1 > DG2, DG4 > DG5 > DG3). The in silico study suggests the mechanism of action of the test compounds to be through the existence of a 3QS1 receptor that possesses an aspartic protease inhibitor of plasmepsin I.

The molecular docking results demonstrated that the ligands (Lig1–Lig5; DG1–DG5) have better docking affinity within the binding pocket of plasmepsin II, even though the native ligand had higher binding energy (Lig0; native ligand; −10.0 Kcal/mol). From the docking results, Lig4 had the highest binding energy of −8.1 Kcal/mol as compared with Lig1 (−7.9 Kcal/mol), Lig2 (−7.0 Kcal/mol), Lig3 (−6.9 Kcal/mol) and Lig5 (−7.4 Kcal/mol). The variation in the binding energy might be due to the interactions of the ligands with various amino acids within the binding pocket in the receptor. The in silico study predicted that the target site of Lig1-Lig5 is in the food vacuole as an aspartic protease inhibitor. Hence, preventing the preferential activity of acid-denatured globin.

5. Conclusions

These findings suggest that the tested compounds could serve as potential inhibitors of key Plasmodium falciparum enzymes, presenting promising therapeutic potential for the development of new antimalarial drugs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G., Y.M.S., M.G.M. and H.H.S.; methodology, D.G., Y.M.S., M.G.M. and H.H.S.; software, D.G., B.H.A. and B.B.; validation, D.G., H.A.N., M.G.M., Y.M.S. and H.H.S.; formal analysis, D.G., B.H.A., A.M.M., M.I.A., M.G.M. and Y.M.S.; investigation, D.G., Y.M.S., M.G.M., M.I.A. and H.H.S.; resources, D.G., A.M., B.B., M.G.M. and H.A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G., Y.M.S., M.G.M. and H.H.S.; writing—review and editing, D.G., H.A.N., A.M., H.H.S. and A.M.M.; supervision, Y.M.S., M.G.M. and H.H.S.; project administration, Y.M.S., M.G.M., H.H.S. and D.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to [ethical concerns about plagiarism].

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to all staff members of the Department of Pharmaceutical and Medicinal Chemistry, Ahmadu Bello University Zaria, Kaduna, Nigeria.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report (2022); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth, J.D. Animal Parasitology; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; p. 549. [Google Scholar]

- Dauda, G.; Haruna, A.K.; Musa, A.M.; Hassan, B.; Mohammed, I.M.; Magaji, M.G. In-vivo antimalarial activity of ethanol leaf extract of Globimetula oreophila (Hook. F) Danser Azadiracchta Indica. Biol. Environ. Sci. J. Trop. 2016, 13, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, C.J.; Rosenfeld, L.C.; Lim, S.S.; Andrews, K.G.; Foreman, K.J.; Haring, D.; Fullman, N.; Naghavi, M.; Lozano, R.; Lopez, A.D. Global malaria mortality between 1980 and 2010: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2012, 379, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, L.H.; Ackerman, H.C.; Su, X.Z.; Wellems, T.E. Malaria biology and disease pathogenesis: Insights for new treatments. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polhill, R.; Wiens, D. Mistletoe of Africa; Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew: Richmond, UK, 1998; 370p. [Google Scholar]

- Burkill, H.M. The Useful Plants of West Tropical Africa; Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew: Richmond, UK, 1985; Volume 4, ISBN 9780947643010. [Google Scholar]

- Dauda, G.; Haruna, A.K.; Hassan, B.; Sani, Y.M.; Haruna, A.; Abdullahi, M.I.; Musa, A.M. Prenylated Quercetin from the Leaves Extract of Globimetula oreophila (Hook. F) Danser. Niger. J. Sci. Res. 2017, 16, 725–729. [Google Scholar]

- Dauda, G.; Ali, B.H.; Muhammed, S.Y.; Muhammad, M.G.; Ismail, A.M.; Muhammad, M.A.; Hassan, H.S. Qualitative and quantitative phytochemical profiling of ethnomedicinal folklore plant-Globimetula oreophila. J. Curr. Biomed. Res. 2023, 3, 1407–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauda, G.; Ali, B.H.; Muhammed, S.Y.; Muhammad, M.G.; Muhammad, M.A.; Hassan, H.S. Levels of trace metals content of crude ethanol leaf extract of Globimetula oreophila (Hook. f) danser growing on Azadirachta indica using atomic absorption spectroscopy. J. Curr. Biomed. Res. 2023, 3, 1397–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauda, G.; Bila, H.A.; Bashar, B.; Sanusi, A.; Yahaya, M.S.; Muhammad, G.M.; Musa, I.A.; Aliyu, M.M.; Hassan, H.S. Exploring the Antimalarial Efficacy of Globimetula oreophila Leaf Fractions in Plasmodium berghei-infected Mice: In Vivo Approach. Sci. Phytochem. 2024, 3, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Dauda, G.; Bila, H.A.; Bashar, B.; Sanusi, A.; Yahaya, M.S.; Muhammad, G.M.; Musa, I.A.; Aliyu, M.M.; Hassan, H.S. Phytochemical investigation and structural elucidation of secondary metabolites from Globimetula oreophila parasitizing Azadirachta indica: A spectroscopic study. Discov. Plants 2024, 1, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaumik, P.; Horimoto, Y.; Xiao, H.; Miura, T.; Hidaka, K.; Kiso, Y.; Wlodawer, A.; Yada, R.Y.; Gustchina, A. Crystal structures of the free and inhibited forms of plasmepsin I (PMI) from Plasmodium falciparum. J. Struct. Biol. 2011, 175, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asojo, O.A.; Gulnik, S.V.; Afonina, E.; Yu, B.; Ellman, J.A.; Haque, T.S.; Silva, A.M. Novel uncomplexed and complexed structures of plasmepsin II, an aspartic protease from Plasmodium falciparum. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 327, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, M.E.; Cenzi, G.; Nunes, R.R.; Andrighetti, C.R.; de Sousa Valadão, D.M.; Dos Reis, C.; Simões, C.M.; Nunes, R.J.; Júnior, M.C.; Taranto, A.G.; et al. Antimalarial activity of 4-metoxychalcones: Docking studies as falcipain/plasmepsin inhibitors, ADMET and lipophilic efficiency analysis to identify a putative oral lead candidate. Molecules 2013, 18, 5276–5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinski, C.A. Lead-and drug-like compounds: The rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004, 1, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).