Abstract

Background: Irisin, a recently discovered muscle-originating hormone, has been found to act as a biomarker of several ailments, while no guideline clearly indicates its testing so far in any particular population category or pathological condition. Objective: We analyzed blood (circulating) irisin in relation to the potential correlations with the evaluation of glucose and bone profile. Methods: This was a prospective, pilot, exploratory study (between December 2024 and August 2025). The enrolled patients were menopausal women aged ≥50. Exclusion criteria: Endocrine tumors, thyroid dysfunction, malignancies, or chronic kidney disease. Baseline (fasting) testing was followed by 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based irisin assay (MyBioSource) was performed. The subjects underwent central Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry (DXA), which provided lumbar, femoral neck and total hip bone mineral density (BMD)/T-score (GE Lunar Prodigy), and lumbar DXA-based trabecular bone score (TBS iNsight). Results: We enrolled 89 females [mean age of 62.84 ± 9.33 years, average years since menopause (YSM) of 15.94 ± 9.23]. Irisin (102.69 ± 98.14 ng/mL) did not correlate with age, YSM, but with body mass index (r = 0.36, p < 0.001). Bone formation marker osteocalcin (r = −0.25, p = 0.018) was negatively associated with irisin, amidst multiple other mineral metabolism assays (including PTH and 25-hydroxyvitamin D). Irisin positively correlated with insulin (r = 0.385, p = 0.0008), HbA1c (r = 0.243, p = 0.022), and HOMA-IR (r = 0.313, p = 0.007). Additional endocrine assays pointed a statistically significant association between irisin and TSH, respectively, ACTH (r = 0.267, p = 0.01, and r = 0.309, p = 0.041, respectively). No correlation irisin-BMD/T-score/TBS was confirmed. Conclusions: Irisin correlates with markers of glucose status (insulin, HOMA-IR, and HbA1c), as well as body mass index and, to a lesser extent, bone metabolism markers. Interestingly, TSH and ACTH correlations open a new (hypothesis-generating) perspective in the endocrine frame of approaching this exerkine. To the best of our knowledge, no distinct study has so far addressed the TBS–irisin relationship or pinpointed the glucose effects on TBS, particularly in menopausal women.

Keywords:

muscle; bone; glycemia; insulin; oral glucose tolerance test; HOMA-IR; glycated hemoglobin A1c; exerkine; TSH; ACTH 1. Introduction

Irisin, a recently discovered muscle-originating hormone, has been proposed to be tested as a biomarker of several ailments (as detected for other myokines/exerkines), particularly amidst the association with glucose metabolism anomalies, but other medical areas are under development as well, such as osteoporosis, cancers, infections, dementia, etc. [1,2,3,4,5]. Prior data show that diabetic patients have a lower irisin than healthy controls, while the subjects with a worse glucose profile, as reflected, for instance, by higher glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), also have a reduced level of this myokine versus individuals with controlled diabetes [1,2,3]. Yet, the results of current studies are not homogenous, and not all studies agree, noting that distinct populations (e.g., with different ages, menopausal status, or different comorbidities) might display a wide range of irisin correlations with the markers of the glucose profile across clinical studies [1,2,3,4].

With respect to distinct glucose anomalies, according to the data we have so far, irisin was found lower in patients diagnosed with types 2 diabetes than controls, and in subjects with pre-diabetes versus diabetes, respectively, in patients with complicat-ed diabetes (e.g. diabetic nephropathy, cardiovascular disease, or diabetic osteosarco-penia, etc.) versus controlled diabetes [6,7,8].

Approximately 75% of the circulating irisin originates from the muscle and to a lesser degree from fat tissue, gut, or pancreas [9,10,11]. Cold exposure or various physical exercises/physical rehabilitation programs act as traditional stimulus of irisin release [12,13,14]. The molecule originates from the fibronectin type III domain-containing 5 protein (FNDC5) [15,16,17]. Moreover, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) coactivator-1α stimulates this complex protein to secrete and release irisin into the blood [18,19,20]. The hormone also interacts with oxidative stress and inflammation pathways, both in animal and human models [17,18,19,20].

Moreover, irisin, a muscle-produced protein, was confirmed to act as a bone-forming agent in the human body, as an additional effect of physical exercise. Irisin might restore bone homeostasis, damaged microarchitecture and mineralization, or even bone turnover, as shown in animal studies. That is why, in a clinical setting, potential correlations with bone turnover markers or bone mineral density assessments might be found. Yet, the number of published studies was low until the present time [17,18,19,20,21].

Overall, currently, the understanding of the irisin-related signaling pathways is based on numerous murine and cell lines experiments, while the landscape of human (clinical) studies remains heterogeneous and rather limited [21,22,23]. Notably, there are no clear indications at this point nor a (clinical) guideline-based recommendation of irisin testing in distinct population subgroups (e.g., diabetic or pre-diabetic groups); this represents a cutting-edge exploration for the muscle–gut–bone–fat–pancreas interplay, with practical applications and clinical benefits to be further identified in the following years [24,25,26].

2. Objective

Taking into consideration the scarcity of the clinical studies with respect to irisin assays and their correlations with various markers of the glucose and bone metabolisms, we aimed to analyze these aspects in a clinical setting including menopausal women.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Study Design

This is a prospective, pilot, clinical (observational), exploratory study in humans, conducted between December 2024 and August 2025 (project “IRI-OP-OB”), from two countries (Department of Endocrinology V, “C.I. Parhon” National Institute of Endocrinology”, Bucharest, Romania and Department of Family Medicine from the State “Nicolae Testemiţanu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Chisinau, Moldova). The current data represents the pilot study and results of the Romanian center. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of “C.I. Parhon” National Institute of Endocrinology”—no. 32 from 30 September 2024.

3.2. Study Population

The enrolled patients are apparently healthy, active menopausal women. Inclusion criteria were signed informed consent for the hospitalization and specific consent for the study (blood testing), age of 50 years or older, confirmed menopausal status (at least one year since the last menstruation, regardless of physiological or surgical menopause).

Exclusion criteria included: active endocrine tumors (e.g., primary hyperparathyroidism, acromegaly, Cushing’s syndrome, neuroendocrine neoplasia, etc.), active thyroid dysfunctions (hyperthyroidism/thyrotoxicosis or hypothyroidism), prior or current diagnosis of any malignancy, chronic kidney disease, bone metabolic diseases, active infectious or inflammatory diseases, previous confirmation of osteoporosis, type 1 or secondary diabetes, prior/current exposure to the following drugs: insulin therapy, corticotherapy, specific anti-osteoporotic medication (oral or intravenous bisphosphonates, denosumab, teriparatide, calcitonin, romosozumab), and glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists (GLP1), estrogens ± progesterone as replacement menopausal therapy.

3.3. Study Protocol

The patients were recruited amid a clinical setting (inpatients) from a tertiary center of endocrinology. After pre-checking the inclusion/exclusion criteria (via evaluating the demographic features, general and endocrine clinical exam, and personal medical records), the subjects who agreed to participate in the study signed the informed consent and then blood testing was performed. Baseline (fasting) testing was followed by the 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) (blood testing at minute 0, 60, and 120).

After serum assays were analyzed, a second round of exclusion was performed if previously undetected anomalies were newly identified and regarded as exclusion criteria, such as hypercalcemia, thyroid function anomalies, or renal failure.

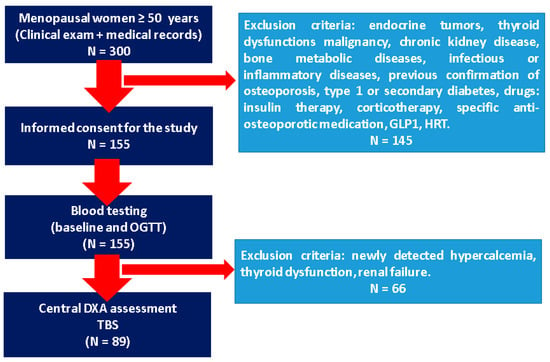

Further on, the subjects underwent central Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry (DXA), which provided lumbar, femoral neck, and total hip bone mineral density (BMD) and associated T-score (GE Lunar Prodigy device), as well as trabecular bone score (TBS) based on lumbar DXA (TBS iNsight software v.3.) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study protocol (abbreviations: DXA = Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry; GLP1 = glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists; HRT = hormone replacement therapy; N = number of patients; OGTT = oral glucose tolerance test; TBS = trabecular bone score).

3.4. Blood Assays

Serum was obtained from whole blood collected in the morning after 8–12 h of fasting. Whole blood was collected in a serum separator tube (SST), allowed to clot for 30 min at room temperature, and centrifuged for 15 min at 1500 g. Serum was aliquoted and stored at −20 °C until assayed.

Irisin was assayed in serum samples by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits following manufacturer protocol (MyBioSource, Inc. San Diego, CA 92195-3308, USA, catalog number MBS706887). Performance characteristics are in the detection range between 3.12 ng/mL and 200 ng/mL, a lower limit of detection of 0.78 ng/mL; intra-assay precision (precision within an assay): coefficient of variation (CV) < 8%; inter-assay precision (precision between assays): CV < 10%. Samples with a concentration higher than 200 ng/mL were diluted 1:5 with Sample Diulent provided by the manufacturer kit.

The mineral metabolism, glucose, and bone-related assays were performed as shown in Table 1. HOMA-IR (Homeostatic Model Assessment-Estimated Insulin Resistance) was calculated based on traditional formula [fasting glycemia (mg/dL) X fasting insulin (µUI/mL) per 405; normal values between 0.7 and 2; insulin resistance being considered at a value of more than 2] [27].

Table 1.

The blood assays according to the study protocol: mineral metabolism biochemistry and hormones, bone turnover markers, glucose, and lipid metabolism markers as well as additional hormones assays.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

MedCalc® Statistical Software version 23.3.7 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium; 2025 [28]) was used for data interpretation. Firstly, we perform the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for normality. Comparison of independent samples was performed using t-test for the parameters with normal distribution and Mann–Whitney test for those without a normal distribution. The data were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile interval (IQR), depending on the data distribution. Pearson correlation for normal distribution and Spearman rank correlation for non-normal distribution were applied. The cut-off of statistical significance was p < 0.05.

3.6. Ethical Aspects

Each patient signed the informed consent. The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethical Board of “C.I. Parhon” National Institute of Endocrinology”, Bucharest, Romania (approval number 32 from 30 September 2024).

4. Results

We enrolled 89 females with a mean age of 62.84 ± 9.33 years. Irisin levels did not correlate with the patients’ age (r = 0.074, p = 0.489). The study population had menopause duration of 15.94 ± 9.23 years, which was not associated with irisin levels (p = 0.486).

Body mass index showed a mean value within the obesity range (≥30 kg/sqm), and was statistically significantly and positively correlated with the circulating irisin, as shown by the r correlation coefficient of 0.36 (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Irisin correlates (in ng/mL). Demographic and clinical data of the study population (89 menopausal women): age (years), menopause duration (years), and body mass index (kg/sqm).

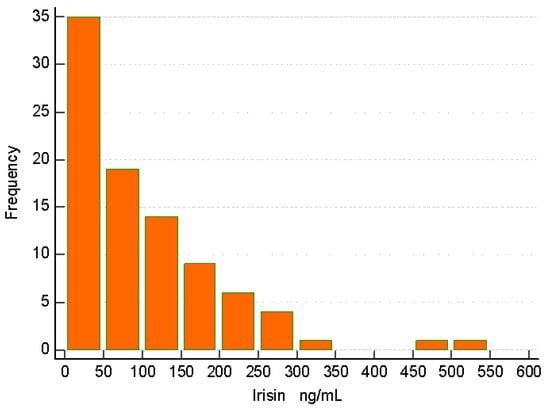

Mean irisin was 102.69 ± 98.14 ng/mL, without any particular distribution around a specific cut-off value (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Histogram of irisin assays in ng/mL. A wide area of irisin values was detected without a particular pattern of distribution.

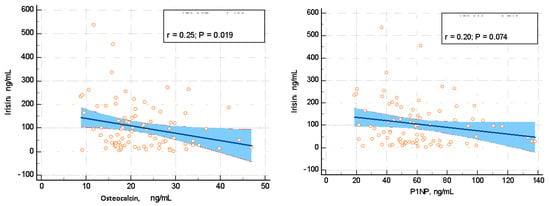

Blood mineral metabolism assays did not correlate with irisin, except for the bone formation marker osteocalcin, which showed a negative correlation with the circulating irisin in terms of a correlation coefficient r = −0.248 (p = 0.018). Other markers of the mineral metabolism, such as total serum calcium, phosphorus, mineral metabolism hormones (e.g., PTH and 25-hydroxyvitamin D), bone formation markers (serum total alkaline phosphatase and P1NP), and bone resorption marker (serum CrossLaps) did not associate with the circulating irisin (p < 0.05). Additionally, the renal function (as reflected by the urea and creatinine) did not correlate with irisin levels (Table 3, Figure 3).

Table 3.

Irisin and potential correlations with the mineral and bone metabolism evaluation (biochemistry and hormonal assays, as well as bone turnover markers) in the study population of 89 menopausal women (r means correlation coefficient; statistical significance is considered at p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Irisin correlation with osteocalcin (ng/mL) and P1NP (n/mL), which represent bone formation markers.

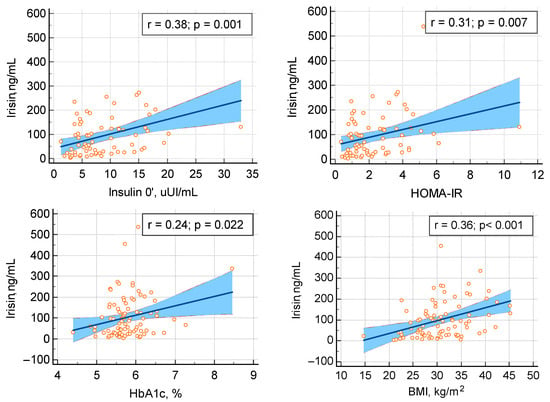

The evaluation of the glucose and lipid metabolism showed that irisin positively correlated with fasting insulin (r = 0.385, p = 0.0008), glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) (r = 0.243, p = 0.022), and HOMA-IR (r = 0.313, p = 0.007). Glycemia (either fasting or during OGTT at minute 60 or 120) did not associate with the circulating irisin. In opposition to the statistically significant positive (medium) correlation between fasting insulin and irisin, insulin assays during OGTT showed no correlation with the circulating irisin, except for a marginal significance of insulin after one hour during OGTT in relationship with irisin (r = 0.231, p = 0.062). None of the study parameters concerning the lipid profile (total cholesterol, triglycerides, and HDL-cholesterol) associated with the serum irisin (p > 0.05) (Table 4, Figure 4).

Table 4.

Circulating irisin and correlations with the clinical exploration of glucose metabolism (fasting assays and oral glucose tolerance test) as well as lipid-profile-related markers in 89 menopausal women.

Figure 4.

Irisin positive (statistically significant) correlation with the evaluation of the glucose metabolism in terms of fasting insulin (upper row, on the left), HOMA-IR (upper row, on the right), HbA1c (lower row, on the left), and body mass index (lower row, on the right) (abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; HOMA-IR = Homeostatic Model Assessment-Estimated Insulin Resistance; HbA1c = glycated hemoglobin A1c).

DXA-derivate BMD/T-score and TBS showed no correlation with circulating irisin. Specifically, we analyzed lumbar bone mineral density and associated T-score, which showed a mean normal value according to the DXA category; femoral neck bone mineral density and associated T-score of −1.1 SD as the median value with interquartile interval between −1.6 and 0.55, which is regarded as osteopenia; and total hip bone mineral density and associated T-score (with a normal mean value). With respect to TBS, the mean value was within the normal range for menopause (of 1.35) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Irisin and BMD analysis based on central DXA (bone mineral density and T-score at lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip) in the study population (N = 89), as well as trabecular bone score, as provided by the lumbar DXA analysis.

Additional endocrine assays showed a statistically significant association between irisin and baseline morning thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and morning plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), respectively (r = 0.267, p = 0.01, and r = 0.309, p = 0.041, respectively). These results suggest that higher irisin may be found in relationship with a higher fasting TSH and ACTH, but, notably, these hormones presented intra-normal variations with a median value within normal ranges: TSH has a median of 1.49 µUI/mL with an interquartile interval between 1.12 and 2.53 µUI/mL, respectively, and ACTH has a median of 11.82 pg/mL with an interval between the first and the third quartile of 8.64–17.06 pg/mL. On the other hand, serum anti-thyroid antibodies, as shown by the testing of anti-thyroperoxidase and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies, did not associate with irisin levels (p > 0.05) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Additional endocrine assays in relationship with serum irisin: thyroid function (TSH and freeT4) and adrenal function (cortisol and ACTH) evaluation in menopausal women (N = 89).

5. Discussion

In this cohort of menopausal women (N = 89), we analyzed the novel biomarker irisin [median (IQR) of 76.75 (27.87–141.80) ng/mL], which represents a promising pointer amidst the clinical practice, despite the fact that the current global level of statistical evidence remains heterogeneous and human research is still an open matter. The correlation between irisin and HbA1c might involve the fact that uncontrolled diabetes potentially associates with a higher level of blood irisin. HOMA-IR, as marker of insulin resistance, was found to be positively correlated with irisin; this means a higher irisin might pinpoint a certain level of insulin resistance. The positive association with fasting insulin also suggests that an increased value or serum irisin may represent a marker of hyperinsulinemia.

In this pilot study, irisin showed no particular age-dependent distribution. Some studies reported irisin’s role in anti-aging defenses, including by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, while general muscle health (as a surrogate of life span’s early indicator) might be reflected by the myokines assays, such as irisin and myostatin [1,29]. However, an age-dependent concentration was not described so far, as confirmed in the present study, and the relationship between irisin and age might actually involve a multifactorial panel, which is centered on the muscle mass and its deterioration, as highlighted in cases with age-related sarcopenia [30,31].

We only included menopausal women, and irisin was not associated with the duration of menopause, as quantified by the years since menopause. Most studies in the bone field involve this distinct population group, while the hormone has been shown to play a complex role across the entire female life span, starting from the timing of puberty and the activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis [32].

A statistically significant positive correlation was found between irisin and BMI, and several studies also reported this type of association, potentially via leptin interplay [33]. Moreover, BMI might be a practical tool to assess the fat tissue in daily practice, but it might not be the optimum tool to reflect the fat–muscle interferences amid the role of blood irisin [34]. For instance, a study conducted by Stengel et al. [34] on 40 females with either anorexia nervosa, normal weight, or obesity, pointed to a higher irisin level in obese versus non-obese patients, with a positive correlation between irisin and BMI (r = 0.5, p < 0.001) [34], which is similar to our results (r = 0.36, p < 0.001).

Irisin was statistically significantly associated with the levels of fasting insulin, HbA1c, and HOMA-IR, which confirmed the results of some other studies [35,36]. For example, Pardo et al. [35] pointed out across a study of 145 females with different BMIs that irisin positively correlated with fasting glucose (r = 0.22, p = 0.0026), fasting insulin (r = 0.34, p < 0.001), and HOMA-IR (r = 0.33, p = 0.001) [35]. On the contrary, Moehlecke et al. [36] showed an inverse correlation between irisin and weight (N = 81), respectively, and HbA1c (r = −0.283, p = 0.024), as well as triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol values (which we cannot confirm) [36]. Of note, Stanković et al. [37] found a direct correlation between irisin and HDL-cholesterol and an inverse association with triglycerides (r = 0.363, p = 0.17, and r = −0.343, p = 0.24, respectively), but no correlation with BMI [37]. These findings suggest that other hidden biases might be involved in the interpretation of the irisin assays [38]. Notably, we excluded patients with type 1 diabetes and insulin therapy, since these circumstances were consistently found to impact the blood irisin levels [39,40]. Moreover, there are not consistent data on GLP1 medication and its irisin influence. Notably, one cell line experiment showed that GLP1 might increase the expression of FNDC5, which, as mentioned, represents an irisin precursor [41].

Regarding the evaluation of the mineral metabolism, irisin showed no specific correlation with either assay (including PTH and 25-hydroxyvitamin D). In this specific instance, some authors suggested that pathological circumstances such as a viral infection might down-regulate the inverse relationship between PTH and irisin, or the relationship between irisin and PTH is not actually linear [42]. Moreover, we did not quantify the supplementation with vitamin D and/or calcium in these menopausal females, since we had a good reflection of the vitamin D status in the 25-hydroxyitamin D and serum total calcium and phosphorus assays. Dell Aquila et al. [43] found that cholecalciferol supplementation in 80 sedentary menopausal women not only corrected vitamin D status, but also increased irisin levels (from the mean level of 0.52 ± 0.27 to the value of 0.80 ± 0.53 ng/mL; p < 0.003) [43].

Furthermore, the bone turnover markers showed an unexpected inverse relationship between irisin and osteocalcin, a pro-bone forming factor [11,44]. Prior studies identified a positive correlation, including in males [45,46]. This might be a random effect, noting that we excluded individuals who were ever exposed to medication against osteoporosis. Also, regarding the interpretation of the bone turnover markers, generally, there are many intra-individual and inter-individual variations, and an adequate analysis may require a much larger cohort [47].

While a limited number of meta-analyses confirmed a lower irisin in osteoporotic versus non-osteoporotic patients, most data sustained inconsistent results with respect to identifying a direct correlation between irisin and DXA-based BMD [48,49]. Since there is not a singular direct action on the skeleton, this type of analysis might not be adequate [49]. With respect to TBS, to our best knowledge, no distinct study addressed this specific matter so far, and this represents a major strength, potentially pinpointing the important glucose metabolism influence on TBS, particularly in menopausal women [50].

Finally, we performed TSH and ACTH assays in order to adequately check the exclusion criteria and found interesting correlations with irisin. One case–control study showed that hypothyroidism increases irisin (N = 74) [51], but so far, a limited number of studies have been published in the clinical field of adrenal- and thyroid-related physiological and pathological circumstances, and further research is necessary [52,53].

The limits of this study are as follows: sample size, cross-sectional design, cases with a mild component of secondary hyperparathyroidism due to vitamin D deficiency were not ruled out, and we did not assess sarcopenia and did not quantify the daily physical activity of the study population. An inclusion of premenopausal women, as well as male subjects, might facilitate the understanding of the irisin testing in clinical practice amidst the evaluation of glucose and bone status. Notably, many variations in the circulating irisin assays come from the lack of testing standardization. Using different kits (mostly ELISA) might explain the heterogeneous landscape of results, which have been reported in clinical studies so far [54]. We point out that there are no specific guidelines for using a particular kit in clinical settings, and this might explain these results to a certain extent. Moreover, commercial ELISA kits might show cross-reactivity with polyclonal antibodies (including MyBioSource ELISA), a question that has been previously asked, and to date, no clear resolution was found until present time. For instance, Albrecht et al. [55] raised the issue that commercial ELISA kits for irisin assays might not stand for its utility as a practical biomarker since the kit potentially detects “cleaved” irisin rather than FNDC5 fragments [55]. Biological validation will require additional studies to place circulating irisin testing in humans as an everyday tool for clinicians. Further longitudinal studies will validate the practical applications of irisin testing in daily practice.

6. Conclusions

According to this pilot study on menopausal women, across a clinical prospective setting, the circulating panel of irisin involves a statistical significant positive correlation with fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, and HbA1c, as well as BMI. We found no association with the bone turnover markers of formation/resorption, except for osteocalcin, neither with DXA-based BMD or TBS. Interestingly, TSH and ACTH correlated with irisin, and this opens up a new perspective in the endocrine frame of approaching this muscle-derivate hormone.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S., N.L.-O., S.V.S., V.C., M.C. (Mara Carsote), A.-M.G., O.-C.S., M.C. (Mihai Costachescu), E.P., A.-I.T., A.P., and D.M.; methodology, L.S., N.L.-O., S.V.S., V.C., M.C. (Mara Carsote), A.-M.G., O.-C.S., M.C. (Mihai Costachescu), E.P., A.-I.T., A.P., and D.M.; software, L.S., N.L.-O., S.V.S., V.C., M.C. (Mara Carsote), A.-M.G., O.-C.S., M.C. (Mihai Costachescu), E.P., A.-I.T., A.P., and D.M.; validation, L.S., N.L.-O., S.V.S., V.C., M.C. (Mara Carsote), A.-M.G., O.-C.S., M.C. (Mihai Costachescu), E.P., A.-I.T., A.P., and D.M.; formal analysis, L.S., N.L.-O., S.V.S., V.C., M.C. (Mara Carsote), A.-M.G., O.-C.S., M.C. (Mihai Costachescu), E.P., A.-I.T., A.P., and D.M.; investigation, L.S., N.L.-O., S.V.S., V.C., M.C. (Mara Carsote), A.-M.G., O.-C.S., A.P., and D.M.; resources, L.S., N.L.-O., S.V.S., V.C., M.C. (Mara Carsote), A.-M.G., O.-C.S., A.P., and D.M.; data curation, L.S., N.L.-O., S.V.S., V.C., M.C. (Mara Carsote), A.-M.G., O.-C.S., M.C. (Mihai Costachescu), E.P., A.-I.T., A.P., and D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, V.C., D.M., S.V.S., and M.C. (Mara Carsote); writing—review and editing, M.C. (Mara Carsote); visualization, L.S., N.L.-O., S.V.S., V.C., M.C. (Mara Carsote), A.-M.G., O.-C.S., M.C. (Mihai Costachescu), E.P., A.-I.T., A.P., and D.M.; supervision, M.C. (Mara Carsote); project administration, M.C. (Mara Carsote); funding acquisition, M.C. (Mara Carsote). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant of the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization, UEFISCDI—the project “Intersecţia dintre metabolism si os: impactul irisinei, markerilor de turnover osos şi inflamatori la paciente cu osteoporoză menopauzală şi obezitate” (“Crossroad of metabolism and bone: the impact of irisin, bone turnover and inflammatory markers in patients with menopausal osteoporosis and obesity”); PN-IV-P8-8.3-ROMD-2023-0262”. The APC was funded by Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization, UEFISCDI—the project “Intersecţia dintre metabolism si os: impactul irisinei, markerilor de turnover osos şi inflamatori la paciente cu osteoporoză menopauzală şi obezitate (IRI-OP-OB)”; PN-IV-P8-8.3-ROMD-2023-0262.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethical Boards of both centers (number 32 from 30 September 2024—Bucharest, Romania, respectively, number 97 from 20 November 2024—Chisinau, Moldova).

Informed Consent Statement

The patients signed the informed consent to participate to the research project.

Data Availability Statement

All available data are in the article.

Acknowledgments

This is part of the project PN-IV-P8-8.3-ROMD-2023-0262. This is also part of a collaboration amid PhD research entitled “Primary hyperparathyroidism: cardio-metabolic, osseous and surgical aspects” (number 28374 from 2 October 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACTH | adrenocorticotropic Hormone |

| BMD | bone mineral density |

| BMI | body mass index |

| CV | coefficient of variation |

| CLIA | Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments |

| DXA | Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| ECLIA | electrochemiluminescence immunoassay |

| FNDC5 | fibronectin type III domain-containing 5 protein |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostatic Model Assessment-Estimated Insulin Resistance |

| HbA1c | glycated hemoglobin A1c |

| HDL | high-density lipoprotein |

| HRT | hormone replacement therapy |

| IQR | interquartile interval |

| N | number of patients |

| OGTT | oral glucose tolerance test |

| PPAR | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor |

| PTH | parathyroid hormone |

| P1NP | procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide |

| SST | serum separator tube |

| TSH | Thyroid Stimulating Hormone |

| T4 | thyroxine |

| TBS | trabecular bone score |

| SD | standard deviation |

References

- Gao, S.; Li, N.; Qi, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Liang, S.; Zhu, W.; Liu, W. Myokines and osteokines in aging-related degenerative diseases: Regulatory networks in the muscle-bone-brain axis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2025, 86, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Qiao, M.Q.; Wang, B.; Fan, J.P.; Gao, F.; Wang, S.J.; Guo, S.Y.; Xia, S.L. Laboratory-based Biomarkers for Risk Prediction, Auxiliary Diagnosis and Post-operative Follow-up of Osteoporotic Fractures. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2025, 23, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrica, M.; Vasiliu, O.; Plesa, A.; Sirbu, O.M. Multinodular and vacuolating neuronal tumor. Rom. J. Mil. Med. 2025, CXXVIII, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nica, S.; Sionel, R.; Maciuca, R.; Csutak, O.; Ciobica, M.L.; Nica, M.I.; Chelu, I.; Radu, I.; Toma, M. Gender-Dependent Associations Between Digit Ratio and Genetic Polymorphisms, BMI, and Reproductive Factors. Rom. J. Mil. Med. 2025, 128, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, I.; Coccurello, R. Irisin: A Multifaceted Hormone Bridging Exercise and Disease Pathophysiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, G. Recent Updates on Diabetes and Bone. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wen, M.; Wang, F. Correlation of serum irisin levels with diabetic nephropathy: An exhaustive systematic appraisal and meta-analytical investigation. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1599423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cigrovski Berkovic, M.; Cigrovski, V.; Ruzic, L. Role of irisin in physical activity, sarcopenia-associated type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular complications. World J. Methodol. 2025, 15, 105462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iglesias, P. Muscle in Endocrinology: From Skeletal Muscle Hormone Regulation to Myokine Secretion and Its Implications in Endocrine-Metabolic Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.N.; Jasim, M.H.; Mahmood, S.H.; Saleh, E.N.; Hashemzadeh, A. The role of irisin in exercise-induced muscle and metabolic health: A narrative review. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 11463–11491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, N.; Carsote, M.; Cocolos, A.; Petrova, E.; Olaru, M.; Dumitrache, C.; Ghemigian, A. The Link Between Bone Osteocalcin and Energy Metabolism in a Group of Postmenopausal Women. Curr. Health Sci. J. 2019, 45, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Hu, Y.; Yu, S.; Bai, H.; Sun, Y.; Gao, W.; Li, J.; Qin, X.; Zhang, X. Exercise in cold: Friend than foe to cardiovascular health. Life Sci. 2023, 328, 121923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, L.K.; Steinberg, G.R. AMPK and the Endocrine Control of Metabolism. Endocr. Rev. 2023, 44, 910–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, S.A.; Pasquarelli-do-Nascimento, G.; da Silva, D.S.; Farias, G.R.; de Oliveira Santos, I.; Baptista, L.B.; Magalhães, K.G. Browning of the white adipose tissue regulation: New insights into nutritional and metabolic relevance in health and diseases. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 19, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, X.; Liang, J.; Kirberger, M.; Chen, N. Irisin, an exercise-induced bioactive peptide beneficial for health promotion during aging process. Ageing. Res. Rev. 2022, 80, 101680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Bristot, V.J.; de Bem Alves, A.C.; Cardoso, L.R.; da Luz Scheffer, D.; Aguiar, A.S., Jr. The Role of PGC-1α/UCP2 Signaling in the Beneficial Effects of Physical Exercise on the Brain. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeremic, N.; Chaturvedi, P.; Tyagi, S.C. Browning of White Fat: Novel Insight into Factors, Mechanisms, and Therapeutics. J. Cell Physiol. 2017, 232, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jodeiri Farshbaf, M.; Ghaedi, K.; Megraw, T.L.; Curtiss, J.; Shirani Faradonbeh, M.; Vaziri, P.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H. Does PGC1α/FNDC5/BDNF Elicit the Beneficial Effects of Exercise on Neurodegenerative Disorders? Neuromol. Med. 2016, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasello, L.; Pitrone, M.; Guarnotta, V.; Giordano, C.; Pizzolanti, G. Irisin: A Possible Marker of Adipose Tissue Dysfunction in Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boström, P.; Wu, J.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Korde, A.; Ye, L.; Lo, J.C.; Rasbach, K.A.; Boström, E.A.; Choi, J.H.; Long, J.Z.; et al. A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature 2012, 481, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargut, T.C.L.; Souza-Mello, V.; Aguila, M.B.; Mandarim-de-Lacerda, C.A. Browning of white adipose tissue: Lessons from experimental models. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2017, 31, 20160051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, E.M.; Constantin, N.; Dragosloveanu, S.; Cergan, R.; Scheau, C. An MRI-Based Method for the Morphologic Assessment of the Anterior Tibial Tuberosity. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbelt, U.; Hofmann, T.; Stengel, A. Irisin: What promise does it hold? Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2013, 16, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, F.L.; Diaconu, C.; Canciu, A.; Ciortea, V.M.; Iliescu, M.G.; Stanciu, M. Medical management and rehabilitation in posttraumatic common peroneal nerve palsy. Balneo PRM Res. J. 2022, 13, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, L.S.; Anderson, B.G.; Conner, J.D.; Wolden-Hanson, T. Circulating irisin levels and muscle FNDC5 mRNA expression are independent of IL-15 levels in mice. Endocrine 2015, 50, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valea, A.; Carsote, M.; Moldovan, C.; Georgescu, C. Chronic autoimmune thyroiditis and obesity. Arch. Balk Med. Union 2018, 53, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/3120/homa-ir-homeostatic-model-assessment-insulin-resistance (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Available online: https://www.medcalc.org (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- LeDrew, M.; Sadri, P.; Peil, A.; Farahnak, Z. Muscle Biomarkers as Molecular Signatures for Early Detection and Monitoring of Muscle Health in Aging. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.F.; Chen, Y.C.; Chang, C.S.; Wu, C.H. Definition and diagnosis of sarcopenia: Asia-Pacific perspectives. Osteoporos. Sarcopenia 2025, 11, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapik, M.; Kuna, J.; Chmielewski, G.; Jaśkiewicz, Ł.; Krajewska-Włodarczyk, M. Alterations in the Myokine Concentrations in Relation to Sarcopenia and Sleep Disturbances: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbagallo, F.; Cannarella, R.; Garofalo, V.; Marino, M.; La Vignera, S.; Condorelli, R.A.; Tiranini, L.; Nappi, R.E.; Calogero, A.E. The Role of Irisin throughout Women’s Life Span. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Peng, X.; Wang, Y.; Cao, R.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, L. What Is the Relationship Between Body Mass Index, Sex Hormones, Leptin, and Irisin in Children and Adolescents? A Path Analysis. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 823424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stengel, A.; Hofmann, T.; Goebel-Stengel, M.; Elbelt, U.; Kobelt, P.; Klapp, B.F. Circulating levels of irisin in patients with anorexia nervosa and different stages of obesity--correlation with body mass index. Peptides 2013, 39, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, M.; Crujeiras, A.B.; Amil, M.; Aguera, Z.; Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Baños, R.; Botella, C.; de la Torre, R.; Estivill, X.; Fagundo, A.B.; et al. Association of irisin with fat mass, resting energy expenditure, and daily activity in conditions of extreme body mass index. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 2014, 857270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moehlecke, M.; Rheinheimer, J.; Crispim, D.; Trindade, M.R.M.; Leitão, C.B. Low irisin levels are associated with increased body weight and an adverse metabolic profile. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 69, e240441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanković, S.; Nikolić, V.V.; Krstić, N. Irisin in Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity: A Biomarker of Metabolic and Lipid Dysregulation. Clin. Med. Insights Endocrinol. Diabetes 2025, 18, 11795514251344029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Tian, M.; Ma, X.; Zhou, J.; Bai, L.; Ding, W. Association of serum irisin levels with glucose and lipid metabolism among adolescents in Yinchuan City from 2017 to 2020. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu J. Hyg. Res. 2024, 53, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulabbas, D.A.; Hassan, E.A. A case-control study to evaluate irisin levels in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 193, 1275–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathia, V.L.; Mendonça, M.I.S.; Simões, D.P.; Perez, M.M.; Alves, B.D.C.A.; Encinas, J.F.A.; Raimundo, J.R.S.; Arcia, C.G.C.; Murad, N.; Fonseca, F.L.A.; et al. Relationship of irisin expression with metabolic alterations and cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A preliminary study. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2023, 69, e20230812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Donelan, W.; Wang, F.; Zhang, P.; Yang, L.; Ding, Y.; Tang, D.; Li, S. GLP-1 Induces the Expression of FNDC5 Derivatives That Execute Lipolytic Actions. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 777026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karras, S.N.; Koufakis, T.; Dimakopoulos, G.; Zisimopoulou, E.; Mourampetzis, P.; Manthou, E.; Karalazou, P.; Thisiadou, K.; Tsachouridou, O.; Zebekakis, P.; et al. Down regulation of the inverse relationship between parathyroid hormone and irisin in male vitamin D-sufficient HIV patients. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2023, 46, 2563–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell Aquila, L.P.; Morales, A.; Moreira, P.; Cendoroglo, M.S.; Elias, R.M.; Dalboni, M.A. Prospective effects of cholecalciferol supplementation on irisin levels in sedentary postmenopausal women: A pilot study. J. Clin. Transl. Endocrinol. 2023, 34, 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Fu, X.; Shi, H.; Jing, J.; Zheng, Q.; Xu, Z. Protective role of irisin on bone in osteoporosis: A systematic review of rodent studies. Osteoporos. Int. 2025, 36, 1815–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayharman, S.; Belviranlı, M.; Okudan, N. The association between circulating irisin, osteocalcin and FGF21 levels with anthropometric characteristics and blood lipid profile in young obese male subjects. Adv. Med. Sci. 2025, 70, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Fan, D.; Sun, L.; Zhang, W.; Yin, F.; Liu, B. Irisin as a predictor of bone metabolism in Han Chinese Young Men with pre-diabetic individuals. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2022, 22, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hu, T.; Ruan, Y.; Yao, J.; Shen, H.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Tan, Q. The Association of Serum Irisin with Bone Mineral Density and Turnover Markers in New-Onset Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2022, 2022, 7808393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, M.; Huang, L.; Luo, J.; Xu, L. The association between circulating irisin levels and osteoporosis in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1388717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Qiao, X.; Cai, Y.; Li, A.; Shan, D. Lower circulating irisin in middle-aged and older adults with osteoporosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause 2019, 26, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chondrogianni, M.E.; Kyrou, I.; Androutsakos, T.; Panagaki, M.; Koutsompina, M.L.; Papadopoulou-Marketou, N.; Polichroniadi, D.; Kaltsas, G.; Efstathopoulos, E.; Dalamaga, M.; et al. Body composition as an index of the trabecular bone score in postmenopausal women. Maturitas 2025, 198, 108273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş, İ.; Altay, M.; Topçuoğlu, C.; Yılmaz, F.M. Circulating levels of irisin is elevated in hypothyroidism, a case-control study. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 60, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Njire Braticevic, M.; Zarak, M.; Simac, B.; Perovic, A.; Dumic, J. Effects of recreational SCUBA diving practiced once a week on neurohormonal response and myokines-mediated communication between muscles and the brain. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1074061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, N.; Hu, Y.; Li, H.; He, X.; Liu, R.; Xu, S.; Zhang, M.; Shi, L. Association of serum irisin concentration with thyroid autoantibody positivity and subclinical hypothyroidism. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49, 3000605211018422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchis-Gomar, F.; Alis, R.; Lippi, G. Circulating irisin detection: Does it really work? Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 26, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, E.; Norheim, F.; Thiede, B.; Holen, T.; Ohashi, T.; Schering, L.; Lee, S.; Brenmoehl, J.; Thomas, S.; Drevon, C.A.; et al. Irisin—A myth rather than an exercise-inducible myokine. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.