Associations Between First-Trimester Cytokines and Gestational Diabetes

Abstract

1. Introduction

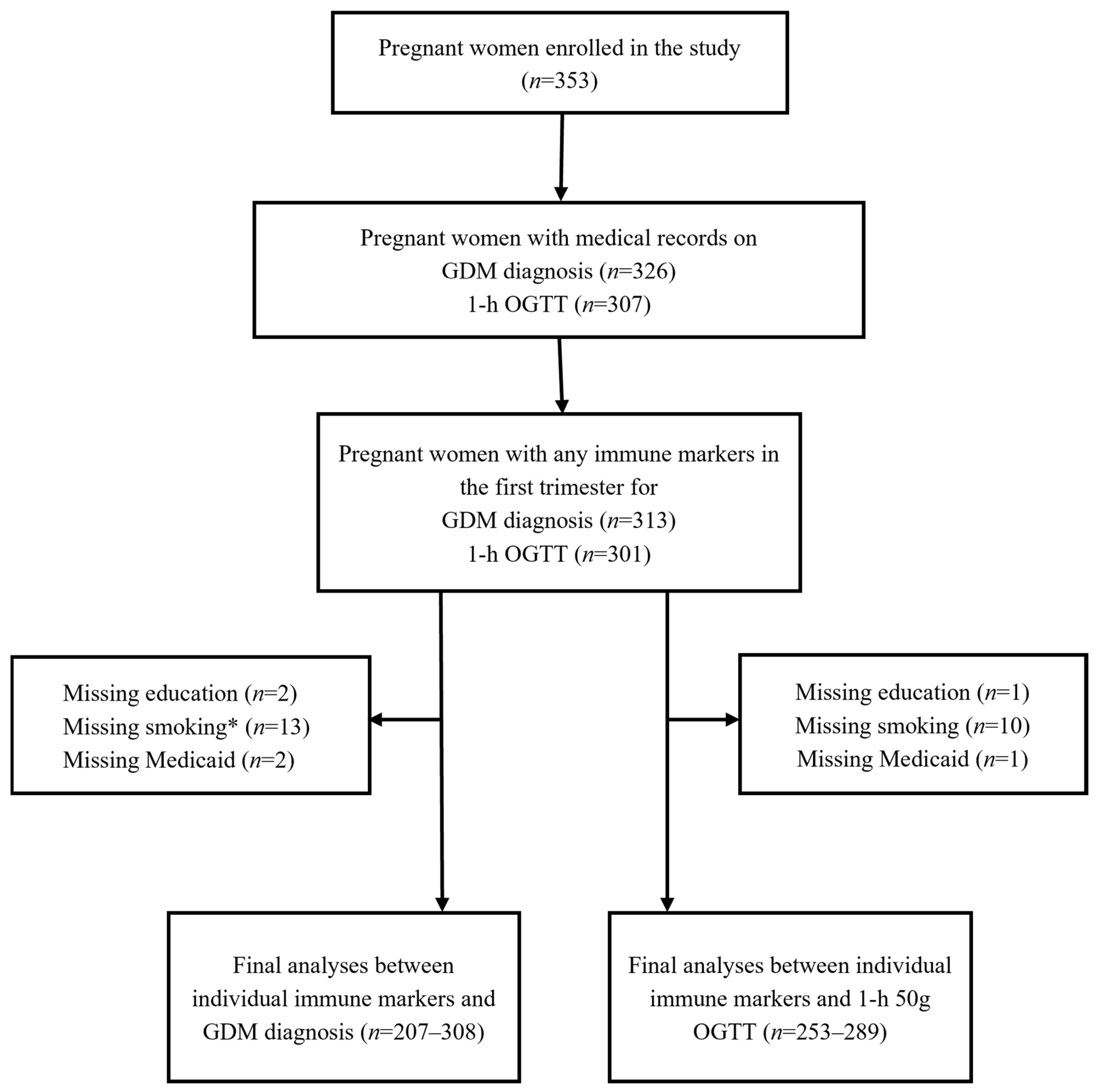

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Overview

2.2. Circulating Immune Markers

2.3. Glucose Measures

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Cohort

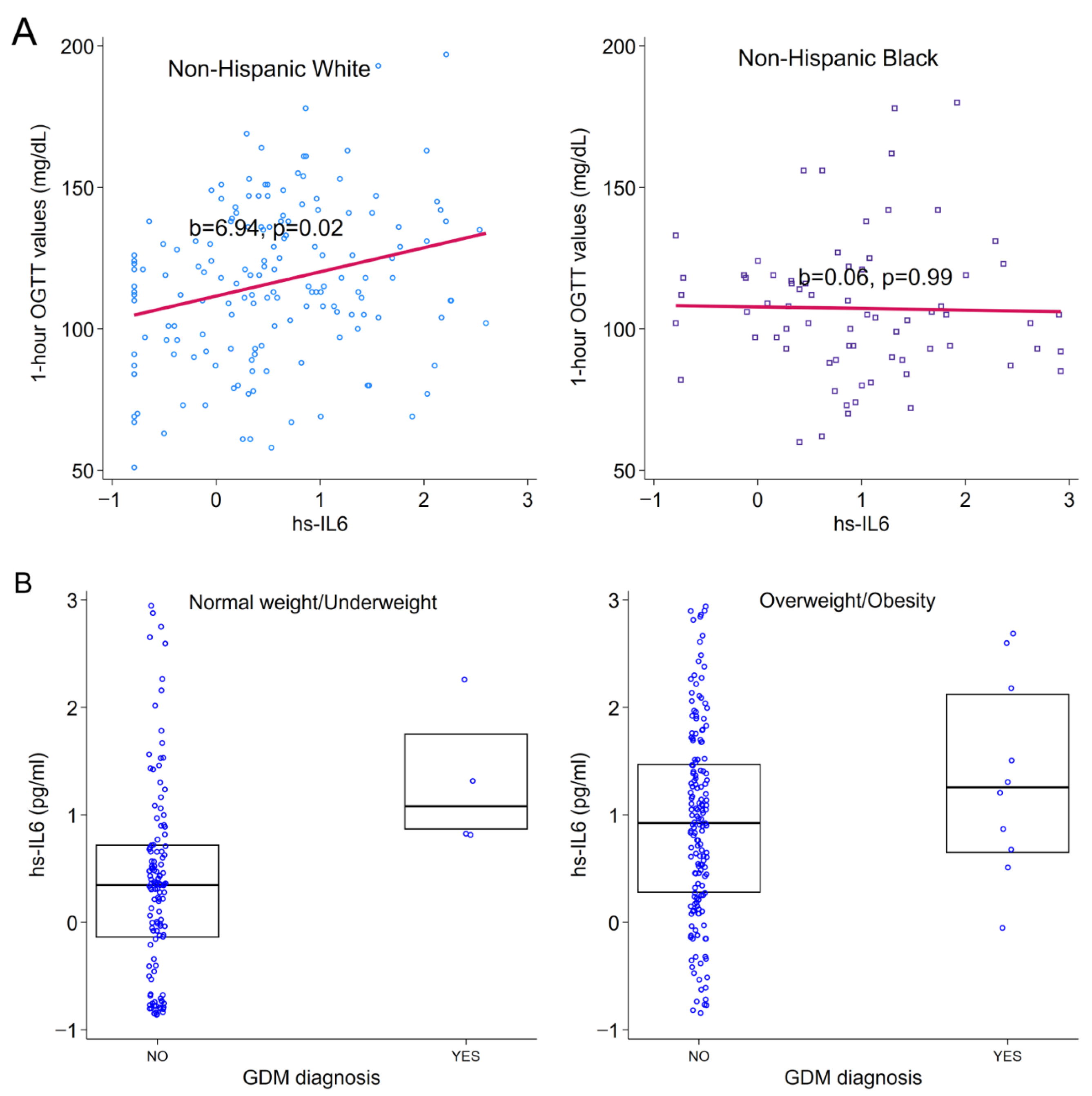

3.2. Associations Between Immune Markers and GDM

3.3. Associations Between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Immune Markers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, C. Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes and Risk of Progression to Type 2 Diabetes: A Global Perspective. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2016, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, B.B.; Magliano, D.J.; Boyko, E.J. IDF diabetes atlas 11th edition 2025: Global prevalence and projections for 2050. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2025, 41, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, P.; Houshmand-Oeregaard, A.; Kelstrup, L.; Lauenborg, J.; Mathiesen, E.R.; Clausen, T.D. Gestational diabetes mellitus and long-term consequences for mother and offspring: A view from Denmark. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 1396–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeting, A.; Wong, J.; Murphy, H.R.; Ross, G.P. A Clinical Update on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Endocr. Rev. 2022, 43, 763–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, L.; Casas, J.P.; Hingorani, A.D.; Williams, D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2009, 373, 1773–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Vargas, L.; Addison, S.S.; Nistala, R.; Kurukulasuriya, D.; Sowers, J.R. Gestational Diabetes and the Offspring: Implications in the Development of the Cardiorenal Metabolic Syndrome in Offspring. Cardiorenal Med. 2012, 2, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firouzi, F.; Ramezani Tehrani, F.; Shaharki, H.; Mousavi, M.; Moradi, N.; Saei Ghare Naz, M. First Trimester Hematological Indices in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-Analysis. J. Endocr. Soc. 2025, 9, bvaf043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, E.C.; Li, M.; Hinkle, S.N.; Cao, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, H.; Kemper, K.; Rennert, L.; et al. Adipokines in early and mid-pregnancy and subsequent risk of gestational diabetes: A longitudinal study in a multiracial cohort. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2020, 8, e001333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abell, S.K.; Shorakae, S.; Harrison, C.L.; Hiam, D.; Moreno-Asso, A.; Stepto, N.K.; De Courten, B.; Teede, H.J. The association between dysregulated adipocytokines in early pregnancy and development of gestational diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2017, 33, e2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassiakos, D.; Eleftheriades, M.; Papastefanou, I.; Lambrinoudaki, I.; Kappou, D.; Lavranos, D.; Akalestos, A.; Aravantinos, L.; Pervanidou, P.; Chrousos, G. Increased Maternal Serum Interleukin-6 Concentrations at 11 to 14 Weeks of Gestation in Low Risk Pregnancies Complicated with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Development of a Prediction Model. Horm. Metab. Res. 2016, 48, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasanayake, A.P.; Chhun, N.; Tanner, A.C.; Craig, R.G.; Lee, M.J.; Moore, A.F.; Norman, R.G. Periodontal pathogens and gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Dent. Res. 2008, 87, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syngelaki, A.; Visser, G.H.; Krithinakis, K.; Wright, A.; Nicolaides, K.H. First trimester screening for gestational diabetes mellitus by maternal factors and markers of inflammation. Metabolism 2016, 65, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Liu, M.; Han, S.; Wu, H.; Qin, R.; Ma, K.; Liu, L.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y. Novel first-trimester serum biomarkers for early prediction of gestational diabetes mellitus. Nutr. Diabetes 2025, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Musharaf, S.; Sabico, S.; Hussain, S.D.; Al-Tawashi, F.; AlWaily, H.B.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; McTernan, P. Inflammatory and Adipokine Status from Early to Midpregnancy in Arab Women and Its Associations with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Dis. Markers 2021, 2021, 8862494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lain, K.Y.; Daftary, A.R.; Ness, R.B.; Roberts, J.M. First trimester adipocytokine concentrations and risk of developing gestational diabetes later in pregnancy. Clin. Endocrinol. 2008, 69, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, H.M.; Lappas, M.; Georgiou, G.M.; Marita, A.; Bryant, V.J.; Hiscock, R.; Permezel, M.; Khalil, Z.; Rice, G.E. Screening for biomarkers predictive of gestational diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol. 2008, 45, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinarello, C.A.; Donath, M.Y.; Mandrup-Poulsen, T. Role of IL-1beta in type 2 diabetes. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2010, 17, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fousteri, G.; Jones, M.; Novelli, R.; Boccella, S.; Brandolini, L.; Aramini, A.; Pozzilli, P.; Allegretti, M. Beyond inflammation: The multifaceted therapeutic potential of targeting the CXCL8-CXCR1/2 axis in type 1 diabetes. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1576371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedderson, M.; Ehrlich, S.; Sridhar, S.; Darbinian, J.; Moore, S.; Ferrara, A. Racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus by BMI. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 1492–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ren, X.; He, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Chen, W. Maternal age and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of over 120 million participants. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 162, 108044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyllenhammer, L.E.; Entringer, S.; Buss, C.; Simhan, H.N.; Grobman, W.A.; Borders, A.E.; Wadhwa, P.D. Racial differences across pregnancy in maternal pro-inflammatory immune responsivity and its regulation by glucocorticoids. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 131, 105333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.G.; Bellissimo, C.J.; Yeo, E.; Fei Xia, Y.; Petrik, J.J.; Surette, M.G.; Bowdish, D.M.E.; Sloboda, D.M. Obesity during pregnancy results in maternal intestinal inflammation, placental hypoxia, and alters fetal glucose metabolism at mid-gestation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, T.; Best, M.; Brunner, J.; Ciesla, A.A.; Cunning, A.; Kapula, N.; Kautz, A.; Khoury, L.; Macomber, A.; Meng, Y.; et al. Cohort profile: Understanding Pregnancy Signals and Infant Development (UPSIDE): A pregnancy cohort study on prenatal exposure mechanisms for child health. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, J.; Womack, S.; Yount, C.; Chowdhury, S.F.; Arnold, M.; Brunner, J.; Duberstein, Z.; Barrett, E.S.; Scheible, K.; Miller, R.K.; et al. Prenatal maternal immune activation predicts observed fearfulness in infancy. Dev. Psychol. 2024, 60, 2052–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anna, V.; van der Ploeg, H.P.; Cheung, N.W.; Huxley, R.R.; Bauman, A.E. Sociodemographic Correlates of the Increasing Trend in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in a Large Population of Women Between 1995 and 2005. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 2288–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feferkorn, I.; Badeghiesh, A.; Baghlaf, H.; Dahan, M.H. The relationship of smoking with gestational diabetes: A large population-based study and a matched comparison. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2023, 46, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kampmann, U.; Knorr, S.; Fuglsang, J.; Ovesen, P. Determinants of Maternal Insulin Resistance during Pregnancy: An Updated Overview. J. Diabetes Res. 2019, 2019, 5320156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, V.; Nagaev, I.; Smith, U. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) induces insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and is, like IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, overexpressed in human fat cells from insulin-resistant subjects. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 45777–45784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senn, J.J.; Klover, P.J.; Nowak, I.A.; Mooney, R.A. Interleukin-6 Induces Cellular Insulin Resistance in Hepatocytes. Diabetes 2002, 51, 3391–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klover, P.J.; Clementi, A.H.; Mooney, R.A. Interleukin-6 Depletion Selectively Improves Hepatic Insulin Action in Obesity. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 3417–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, T.; Yang, F.; Pubu, C. Advancements in the understanding of mechanisms of the IL-6 family in relation to metabolic-associated fatty liver disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1642436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sominsky, L.; O’Hely, M.; Drummond, K.; Cao, S.; Collier, F.; Dhar, P.; Loughman, A.; Dawson, S.; Tang, M.L.K.; Mansell, T.; et al. Pre-pregnancy obesity is associated with greater systemic inflammation and increased risk of antenatal depression. Brain Behav. Immun. 2023, 113, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, I.; Schleger, F.; Hartkopf, J.; Veit, R.; Breuer, M.; Schneider, N.; Pauluschke-Fröhlich, J.; Peter, A.; Preissl, H.; Fritsche, A.; et al. Pre-pregnancy BMI but not mild stress directly influences Interleukin-6 levels and insulin sensitivity during late pregnancy. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2022, 27, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palermo, B.J.; Wilkinson, K.S.; Plante, T.B.; Nicoli, C.D.; Judd, S.E.; Kamin Mukaz, D.; Long, D.L.; Olson, N.C.; Cushman, M. Interleukin-6, Diabetes, and Metabolic Syndrome in a Biracial Cohort: The Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke Cohort. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellulu, M.S.; Patimah, I.; Khaza’ai, H.; Rahmat, A.; Abed, Y. Obesity and inflammation: The linking mechanism and the complications. Arch. Med. Sci. 2017, 13, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prins, J.R.; Gomez-Lopez, N.; Robertson, S.A. Interleukin-6 in pregnancy and gestational disorders. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2012, 95, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, E.C.; Reynolds, S.M.; Cox, C.; Jacobson, L.P.; Magpantay, L.; Mulder, C.B.; Dibben, O.; Margolick, J.B.; Bream, J.H.; Sambrano, E.; et al. Multisite comparison of high-sensitivity multiplex cytokine assays. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2011, 18, 1229–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 28.9 (4.68) |

| Race | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 176 (55.0%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 83 (25.9%) |

| Hispanic | 34 (10.6%) |

| Others | 27 (8.4%) |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 121 (38.1%) |

| Some college | 45 (14.1%) |

| Bachelor or above | 152 (47.8%) |

| Early-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 28.2 (7.03) |

| Nulliparous | 108 (33.7%) |

| Medicaid coverage | 150 (47.2%) |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 23 (7.5%) |

| Cytokines | 1 h 50 g OGTT Levels a | GDM Diagnosis b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | B | 95% CI | n | OR | 95% CI | |

| CRP | 277 | 0.63 | −0.86, 2.12 | 295 | 0.85 | 0.65, 1.11 |

| TNFα | 285 | 0.42 | −7.67, 8.50 | 303 | 2.74 | 0.64, 11.75 |

| hs-IL6 | 270 | 3.76 | 0.21, 7.32 | 295 | 2.36 | 1.17, 4.77 |

| IL6 | 272 | −1.77 | −6.63, 3.08 | 288 | 0.52 | 0.20, 1.36 |

| IL1β | 272 | −0.14 | −6.79, 6.52 | 289 | 0.81 | 0.26, 2.58 |

| IL8 | 270 | −0.65 | −5.74, 4.44 | 284 | 0.80 | 0.33, 1.97 |

| IL6/IL10 | 263 | −3.80 | −19.53, 11.93 | 279 | 0.11 | 0.003, 3.69 |

| TNFα/IL10 | 276 | 1.38 | −15.84, 18.60 | 294 | 7.07 | 0.73, 68.67 |

| TNFα/IL4 | 263 | 11.58 | −19.12, 42.27 | 284 | 26.39 | 0.46, 1512.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Meng, Y.; Thornburg, L.L.; Groth, S.W.; Barrett, E.S.; Miller, R.K.; O’Connor, T.G. Associations Between First-Trimester Cytokines and Gestational Diabetes. Diabetology 2026, 7, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology7020022

Meng Y, Thornburg LL, Groth SW, Barrett ES, Miller RK, O’Connor TG. Associations Between First-Trimester Cytokines and Gestational Diabetes. Diabetology. 2026; 7(2):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology7020022

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeng, Ying, Loralei L. Thornburg, Susan W. Groth, Emily S. Barrett, Richard K. Miller, and Thomas G. O’Connor. 2026. "Associations Between First-Trimester Cytokines and Gestational Diabetes" Diabetology 7, no. 2: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology7020022

APA StyleMeng, Y., Thornburg, L. L., Groth, S. W., Barrett, E. S., Miller, R. K., & O’Connor, T. G. (2026). Associations Between First-Trimester Cytokines and Gestational Diabetes. Diabetology, 7(2), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology7020022