Abstract

Background/Objectives: In all types of diabetes, elevated blood glucose levels cause pathological changes in skeletal muscle, primarily due to oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Regular exercise can help mitigate these effects; however, the underlying mechanisms, particularly those involving the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), remain incompletely understood. This study aimed to explore the effects of aerobic exercise training (AET) on oxidative stress and the expression of mPTP components in the skeletal muscle of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Methods: Male Wistar rats were randomly divided into three groups: Healthy Sedentary (H-SED), Diabetic Sedentary (D-SED), and Diabetic Exercise-trained (D-EXER); n = 6 per group. The D-EXER group performed AET (0° slope) 5 days/week for 8 weeks. After the intervention period, body weight and fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels were measured, and soleus muscles were collected and analyzed for oxidative stress biomarkers, Western blotting, and gene expression using qRT-PCR. Results: Following an 8-week intervention, AET reduced FBG concentrations. Accordingly, in the soleus muscles of the D-EXER group, ROS levels decreased, and redox balance was improved compared to the D-SED group. Exercise training reduced CypD and Casp9 mRNA expression and increased Bcl-2 mRNA expression, whereas Ant1 mRNA expression was only slightly altered. CypD protein expression was decreased in exercised diabetic rats, while VDAC1 protein and mRNA levels remained unchanged. In the D-EXER group, there were significant inverse correlations between CypD and Casp9 mRNA expression levels and glutathione redox state. Conclusions: The current study suggests that 8 weeks of AET, in addition to reducing hyperglycemia, may favorably influence oxidative balance and the expression of mPTP-related molecular components in diabetic skeletal muscle.

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic, progressive metabolic disorder characterized by persistently elevated blood glucose levels resulting from insufficient insulin secretion (type 1) or impaired insulin action (type 2) [1,2]. According to the International Diabetes Federation [3], more than 580 million people currently live with diabetes worldwide, and this number is projected to rise to 852.5 million by 2050. Therefore, diabetes is becoming one of the leading causes of global morbidity and mortality.

One of the significant complications associated with diabetes is skeletal muscle impairment, which has become a critical aspect of the disease’s pathophysiology [4,5]. Skeletal muscle plays a vital role in insulin-mediated glucose uptake and maintaining overall glucose homeostasis [4,6]. Both forms of diabetes lead to metabolic and functional changes in muscle tissue, referred to as diabetic myopathy [6,7].

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a central feature of diabetic myopathy. In diabetic skeletal muscle, reductions in mitochondrial content, structural integrity, and oxidative capacity impair ATP production and energy metabolism [8,9,10,11,12]. These alterations are closely associated with excessive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which disrupt the redox balance and promote oxidative damage to cellular macromolecules [13].

Although mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress are tightly interconnected in diabetes, the molecular mechanisms linking these processes, particularly those involving the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), remain incompletely defined [8,14,15]. In particular, the contribution of mPTP-related molecular components to skeletal muscle dysfunction in diabetes remains incompletely elucidated.

mPTP has emerged as a critical regulator of mitochondrial integrity under both physiological and pathological conditions. Also known as the “mitochondrial megachannel”, the mPTP is a multiprotein complex comprising components of the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes and the matrix [16,17,18]. Its core constituents include the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC1), the adenine nucleotide translocator (ANT1), and cyclophilin D (CypD) [19,20,21,22,23,24], with additional modulation by pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bax and Bcl-2 [16]. Under diabetic conditions, hyperglycemia-associated calcium overload and oxidative stress promote prolonged mPTP opening [25,26], resulting in increased membrane permeability, mitochondrial swelling, cytochrome c release, and activation of cell death pathways [27,28].

Altered mPTP regulation has been documented in metabolically active tissues highly vulnerable to mitochondrial dysfunction, including cardiac and skeletal muscle [29,30]. CypD plays a pivotal role in sensitizing the pore to pathological opening [24], and its inhibition, either pharmacological or genetic, has been shown to improve glucose tolerance and attenuate insulin resistance in high-fat diet models [29]. Diabetic hearts exhibit elevated CypD levels, reduced cytochrome c and Bcl-2, and increased Bax expression [31]. In skeletal muscle, dysregulated mPTP opening has been directly linked to mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired insulin signaling [32]. However, the extent to which mPTP-related gene expression changes contribute to redox imbalance and apoptotic signaling in diabetic skeletal muscle remains to be further explored. Regular physical activity, particularly aerobic exercise training (AET), induces beneficial mitochondrial adaptations and is widely recognized as an effective strategy for improving metabolism in individuals with diabetes [33,34,35]. In skeletal muscle, AET enhances glucose uptake, reduces insulin resistance, and increases mitochondrial efficiency. These improvements are facilitated by the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase and the increased expression of glucose transporter 4 [36,37]. Additionally, exercise training has been shown to reduce mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis [38,39] and decrease susceptibility to mPTP opening in mitochondria isolated from hyperglycemic rats [40]. In obese individuals, exercise appears to inhibit mPTP opening and downregulate apoptotic markers in skeletal muscle [38].

Despite growing evidence of the protective effects of exercise on mitochondria, the specific impact of AET on mPTP in the skeletal muscle of individuals with diabetes remains poorly understood. In this context, exercise-induced modulation of mPTP-related molecular markers may provide insight into potential mechanisms linking redox balance and mitochondrial integrity. Based on this, we hypothesized that AET may preserve mitochondrial function and attenuate apoptotic signaling in skeletal muscle by reducing oxidative stress and modulating mPTP-related gene expression. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the effects of AET on the expression of mitochondrial components associated with the mPTP and on oxidative stress markers in the soleus muscle of streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statements

All research protocols were approved by the Institutional Committee on the Use of Animals at the Universidad de Guanajuato (Code: CEPIUG-P26-2023) prior to conducting the study. All animal experiments adhered to the ARRIVE 2.0 guidelines [41] and complied with ethical standards, including Mexican regulations for the care and use of laboratory animals (NOM-062-ZOO-1999) [42].

2.2. Animals

The experiments were conducted on male Wistar albino rats (body weight 83.5 ± 7.6 g at the beginning of the experiment). Rats were obtained from our local breeding colonies at the Department of Applied Labor Sciences, University of Guanajuato, Mexico. The animals were housed in a pathogen-free environment in polycarbonate cages with smooth, rounded edges, three animals per cage, and were properly identified. The bedding for the animals was prepared from wood shavings and changed every three days. After STZ administration, the animals urinate more frequently, requiring daily bedding changes. The study was conducted in a pathogen-free, controlled environment with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle at 20 ± 2 °C. Animals were provided with a standard rat chow and water ad libitum. Standard qualitative criteria, such as alterations in posture, grooming behavior, locomotor activity, food and water intake, and fur condition, were used daily to monitor all animals for signs of stress or discomfort.

2.3. Experimental Design

The research involved 18 male Wistar rats. The animals were randomly assigned to three experimental groups (n = 6 per group): healthy sedentary (H-SED), diabetic sedentary (D-SED), and diabetic exercise-trained (D-EXER).

The sample size was determined based on our working group’s prior experience with diabetic rats. A sample size estimation was performed in G*Power (version 3.1), with α = 0.05, power (1–β) = 0.80, indicating that with n = 6 across three groups, the design is sensitive to detect large effects. This sample size was defined in accordance with ethical principles aimed at minimizing animal use while allowing detection of biologically relevant effects, in compliance with the 3Rs principles [43], NOM-062-ZOO-1999, and ARRIVE 2.0 guidelines [41].

To induce diabetes, a single dose of STZ (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) of 100 mg/kg body weight was administered intraperitoneally. The STZ was freshly dissolved in 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 4.5). Control rats (normoglycemic) received an intraperitoneal injection of citrate buffer instead of STZ. The induction was confirmed to be successful 72 h after the STZ injection. Blood glucose concentrations were measured by collecting a small blood sample from the tail and analyzing it with a glucometer (Accu-Chek Performa; Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Rats with blood glucose levels ≥300 mg/dL were considered diabetic [44] and included in the study.

Animals in the control groups (H-SED and D-SED) were treated in the same manner as those in the exercise-trained group (D-EXER). All groups were evaluated during the same period. The experimental animals were not treated with insulin.

One week after STZ or vehicle administration (day 0; the start of the experimental protocol), body weight and fasting blood glucose were measured at 0 (baseline), 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks to assess the progression of induced diabetes (hyperglycemia) and the effect of exercise. The body weight (BW) of each group of animals was measured at the same time of day by an animal weighing scale (Ohaus, Voyager v16120, Pine Brook, NJ, USA). Blood glucose concentrations were measured in tail samples using a glucometer (Accu-Chek Performa; Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and blood test strips. The measurements were performed after a 12-h fast.

Once the intervention was completed, the animals in all groups were fasted for 12 h and euthanized by cervical dislocation. The soleus muscles of both legs were removed, and all samples were immediately immersed in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further processing. Following tissue preservation, a homogenate was prepared for biochemical testing, Western blotting, and RT-qPCR.

2.4. Exercise Training Program

Rats ran on a treadmill (Weslo CADENCE 78E; Icon Health & Fitness, Logan, UT, USA) that was modified to include an acrylic chamber with nine lanes and motion sensors that, when needed, delivered mild air stimuli to promote movement. Animals were progressively conditioned to avoid this stimulus, which did not induce observable signs of distress. To prevent biomechanical stress and standardize mechanical workload across animals, the treadmill was kept at a constant 0° inclination.

Before the main experimental phase began, the rats underwent a 2-day familiarization/acclimation period on the stationary treadmill, with each session lasting 1 h. Subsequently, the rats underwent four days of conditioning, during which they were placed on the treadmill. During this phase, the running time and speed were progressively increased from 10 m/min to 15 m/min (5–20 min/day) to condition the training program’s time and speed requirements. This initial brief period was primarily designed to acclimate the rats to the treadmill environment, reduce psychological stress, and train them to run in the proper direction.

The moderate-intensity aerobic training program consisted of 5-min cycles at 15 m/min in the initial phase, 20-min cycles at 20 m/min in the core phase, and 5-min cycles at 15 m/min in the final phase. Thus, each session lasted 30 min. The protocol was applied for 8 weeks, 5 days a week (Monday to Friday), between 6:00 and 7:00 p.m. All rats completed training without struggling. Before an experiment (session), treadmill intensity was measured and adjusted by using a tachometer (Extech 461995 Laser Photo/Contact; Extech Instruments, Nashua, NH, USA) to verify or control the actual belt speed. The tachometer provides an objective, real-time measurement of the treadmill motor’s rotational speed, which is then used to ensure the desired running intensity (meters per minute) is accurate and consistent with the established protocol [45,46].

This protocol was developed based on research on aerobic exercise in rodents [47,48], particularly in Wistar rats, which determined appropriate ranges of duration and speed for moderate-intensity exercise [49,50]. These studies also demonstrated benefits, such as biochemical and molecular adaptive changes in diabetic rats [50,51,52].

2.5. Detection of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Levels

The fluorescent probe 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; D6883) was used to measure ROS accumulation in soleus muscles, according to the method described by [53]. For this estimation, muscle tissue was homogenized in Krebs–Ringer solution (118 mM NaCl, 4.75 mM KCl, 1.18 mM MgSO4, 24.8 mM NaHCO3, 1.18 mM KH2PO4; pH 7.4) using a tissue homogenizer (D-160 Handheld Homogenizer; DLAB Scientific, Beijing, China), keeping the tissue sample on ice.

For the assay, 0.5 mg of protein was incubated in 2 mL of buffer containing 100 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 3 mM KH2PO4, and 3 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.4) with 12.5 µM H2DCFDA for 15 min on ice under constant shaking. Fluorescence changes were recorded at 0 and 60 min using excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 nm and 520 nm, respectively, in a spectrofluorophotometer (Shimadzu RF-5301PC, Kyoto, Japan).

To measure nonspecific fluorescence from the environment, media components, or the probe itself, concurrent background-correcting controls included one containing only the assay buffer (with the H2DCFDA probe but without a biological sample). To account for the intrinsic autofluorescence of the sample or buffer, an additional control was a sample incubated without the H2DCFDA probe. All other readings were subtracted from these values. ROS levels were normalized to total protein content using a Bradford assay [54] and expressed as arbitrary units (fluorescence units) per mg of protein.

2.6. Determination of Glutathione Levels in Skeletal Muscle Tissue

To quantify total glutathione (GSH + GSSG), oxidized glutathione (GSSG), and reduced glutathione (GSH), an enzymatic recycling method [55] was used with minor modifications. 0.5 mg of protein from muscle homogenates was resuspended in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.6% sulfosalicylic acid, and 5 mM disodium EDTA. The samples were sonicated using a Fisherbrand™ Sonifier (tapered microtip, 20 W output, continuous duty cycle) for three alternating cycles of sonication and ice incubation, followed by two freeze–thaw cycles, and then centrifuged at 7200 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C to obtain the clarified supernatant.

For the assay, 90 µL of supernatant was combined with a reaction mixture containing 5 mM disodium EDTA, 0.1 mM 5,5-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and 100 mU/mL glutathione reductase in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer. After 5 min preincubation at room temperature, the reaction was initiated by the addition of 50 μM β-NADPH (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Absorbance at 412 nm was measured for 5 min at 30 °C using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1900, Kyoto, Japan). To determine GSSG, samples were preincubated with 0.2% 4-vinylpyridine for 1 h at room temperature to derivatize reduced glutathione. GSH concentration was calculated by subtracting GSSG from total glutathione, and the redox ratio (GSH/GSSG) was computed accordingly.

2.7. Total RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

For total RNA extraction, soleus muscle samples were homogenized in TRIzol (TRI Reagent, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) using the method described by [56], with minor modifications. RNA quality and quantity were measured spectrophotometrically by determining the 260/280 nm absorbance ratio using the BioPhotometer (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 2 μg of RNA using a cDNA synthesis kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The QuantiFast SYBR Green PCR Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) was used to perform quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reactions (qRT-PCR) on a QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Foster City, CA, USA).

Primer sequences were designed using information from the GenBank public database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. The following primers were used in this experiment: Cyclophilin D (CypD), forward 5′-GGGCTCTTGTGAAAGTCCCA-3′ and reverse 5′-AATTCACATTGAGCAGACAGGC-3′ (NM_172243.2); Vdac1, forward 5′-CAAGAACGTCAATGCGGGTG-3′ and reverse 5′-GGAATGGGGTTTCCGCTGTA-3′ (NM_031353.3); Ant1, forward 5′-GATGCTGCCAGACCCCAAGAAT-3′ and reverse 5′-CATGCCTCTCAGTACGTTGGA-3′ (NM_053515.2); Casp9, forward 5′-CCCTCACTCTGCTCTTCCTAC-3′ and reverse 5′-CCCCACTAGGGTAACCAACAG-3′ (NM_031632.3); Bcl-2, forward 5′-AGAGCGTCAACAGGGAGATG-3′ and reverse 5′-GATGCCGGTTCAGGTACTCAG-3′ (NM_016993.2); 18S, forward 5′-GCAAATTACCCACTCCCGAC-3′ and reverse 5′-CCGCTCCCAAGATCCAACTA-3′ (XR_005503126.2). The results were normalized to the 18S expression level. The amplification efficiency of each sample was calculated from standard curve experiments, and target gene expression was evaluated using the comparative delta-delta cycle threshold (ΔΔCT) method [57].

2.8. Western Blot

For the identification and evaluation of protein levels, the methodology described by [58,59] was followed, with slight modifications. Briefly, skeletal muscle tissue was suspended in lysis buffer (Triton X-100 0.05%, urea 4 M; NaCl 50 mM, SDS 0.03%; Tris-HCl 50 mM; MOPS 5 mM; HEPES 50 mM; Glycerol 5%; EGTA 1 mM; EDTA 1 mM; Na3VO4 0.5 mM; NaF 50 mM; β-glycerophosphate 10 mM; 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 5 mM DTT). All procedures were performed on ice to minimize protein degradation.

Subsequently, the muscle was mechanically homogenized using a rotary homogenizer. The total extracts were centrifuged at 20,000× g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was recovered and stored at −80 °C until further analysis. Protein quantification was performed using the Bradford method. 30 µg of protein extract per lane were denatured and separated by SDS-PAGE in Bio-Rad vertical electrophoresis chambers. Then, the gels were transferred to a PVDF membrane using a Semi-Dry Bio-Rad chamber. After blocking, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies: anti-CypD (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), anti-VDAC1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), and anti-β-actin (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with the respective HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. The membranes were developed by chemiluminescence using luminol and peroxide solutions. Densitometric analysis of Western blots was carried out using the ImageJ software (version 1.54g) for protein quantification.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from six independent experiments (n = 6 animals per group). All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Prior to inferential analyses, data distribution was assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test.

Body weight and fasting blood glucose, which were measured repeatedly over time, were analyzed using a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with group as the between-subject factor (H-SED, D-SED, and D-EXER) and time (weeks 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8) as the within-subject factor, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. When appropriate, paired two-tailed t-tests were used to compare two time points within the same group.

All other endpoint variables, ROS, GSH/GSSG levels, and mRNA and protein expression were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with group as the independent factor, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to assess relationships between mRNA expression levels and the GSH/GSSG ratio. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

An assessment of study sensitivity was performed in G*Power (version 3.1) to estimate the magnitude of effects that could be detected given the observed variability. Based on the standard deviation of the most variable outcome (caspase-9 mRNA expression), the present study was sufficiently powered to detect large effect sizes.

To control the family-wise type I error rate in multiple testing, a Bonferroni correction was applied when appropriate. Given that 12 independent outcome variables were analyzed, the threshold adjusted for statistical significance was set at p < 0.004 (0.05/12). p-values below this threshold are considered statistically significant, while those between p = 0.004 and p = 0.05 are interpreted as suggestive. All statistical tests were two-tailed.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Aerobic Exercise Training on Fasting Blood Glucose Levels and Body Weight in Diabetic Rats

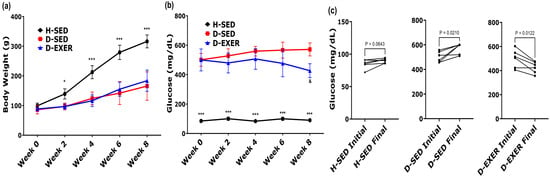

The profiles of body weight and fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels over eight weeks are presented in Figure 1. The data were analyzed at baseline (1–7 days; 0 weeks) and at the 2nd, 4th, 6th, and 8th weeks. Changes over time were assessed for group differences using a repeated-measures ANOVA, focusing on the group-by-time interaction as the primary test of interest.

Figure 1.

Changes in body weight and fasting blood glucose after 8 weeks of aerobic exercise in STZ-induced diabetic rats. (a) Body weight (BW) and (b) fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels were measured every two weeks over the 8-week experimental period. Longitudinal data were analyzed using a repeated-measures two-way ANOVA with time and group as factors, followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test. (c) Comparison of initial (baseline) and final (week 8) FBG values within each experimental group. Individual paired values are shown, with lines connecting measurements from the same animal. Normality assumptions were evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Paired comparisons were performed using a paired Student’s T-test. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6 per group). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.004 after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Differences with p-values between 0.004 and 0.05 are considered suggestive. Symbols indicate statistically significant differences between groups at the same time point based on repeated-measures two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001 vs. D-SED and D-EXER groups; and p < 0.05 vs. D-SED group. Healthy sedentary (H-SED); sedentary diabetic (D-SED); diabetic exercise-trained (D-EXER).

Regarding body weight (Figure 1a), all groups exhibited the same baseline body weight at the start (0 weeks). Subsequently, the H-SED group experienced a markedly greater weight gain (p < 0.001) than the diabetic groups (D-SED and D-EXER) at all measured time points, including by the end of the 8-week intervention. However, no significant differences in weight change were observed between the D-SED and D-EXER groups.

Fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels were significantly higher in the diabetes groups from week 0 onward (515.65 ± 20.14 mg/dL) than in the H-SED or control normoglycemic group (81.30 ± 3.07 mg/dL; p < 0.001) (Figure 1b), confirming the diabetic condition. Over the eight weeks, FBG levels (Figure 1b) remained significantly higher in the diabetic groups (D-SED and D-EXER) than in the H-SED group (p < 0.001). However, from week 6 onward, the D-EXER group showed lower glucose levels than the D-SED group. By the 8th week, the D-EXER group showed a tendency toward lower mean FBG values than the D-SED group (p = 0.0138).

Furthermore, results from the paired t-test for the D-EXER group indicated an FBG p-value of 0.0122, which did not reach statistical significance after Bonferroni correction (adjusted threshold p < 0.004) (Figure 1c). These results should be interpreted as a suggestive trend.

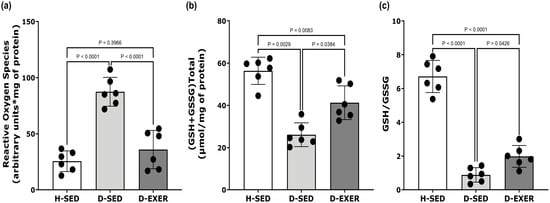

3.2. Effects of Aerobic Exercise Training on Oxidative Stress Markers in Soleus Muscles

Figure 2 shows the oxidative stress parameters measured in the soleus muscles of the different experimental groups. In Figure 2a, the changes in ROS levels in diabetic rats after 8 weeks of treadmill training are shown. There was a statistically significant increase in ROS levels between the H-SED and D-SED groups, with a 69.75% increase (p < 0.004). Additionally, ROS levels were significantly reduced by 57.79% in the D-EXER group compared to the D-SED group (p < 0.004).

Figure 2.

Effect of exercise training on (a) levels of ROS, (b) total glutathione content, and (c) reduced glutathione (GSH)/glutathione disulfide (GSSG) ratio in the soleus muscles of STZ-induced diabetic rats. The black dots represent individual animal variability. Each dataset is expressed as mean ± SD, with n = 6 per group. The data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc tests. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.004 after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Differences with p-values between 0.004 and 0.05 are considered suggestive. Healthy Sedentary (H-SED); Diabetic Sedentary (D-SED); Diabetic Exercise-Trained (D-EXER).

Figure 2b illustrates that the total glutathione concentrations (GSH + GSSG) were lower in the soleus muscles of the D-SED group compared to the H-SED rats, showing a decrease of 49.94% (p < 0.004). Exercise training in the D-EXER group resulted in a 35.36% increase in total glutathione levels compared to the D-SED group; however, this change did not reach statistical significance after Bonferroni correction (p = 0.0384).

Furthermore, the redox status, as indicated by the GSH/GSSG ratio, was markedly reduced in diabetic rats, with a 87.69% decrease compared with the H-SED group (p < 0.0001), as shown in Figure 2c. On the other hand, exercise training in the D-EXER group was associated with a trend toward improved redox status, resulting in a 53.01% increase in the GSH/GSSG ratio compared with the D-SED group (p = 0.0426).

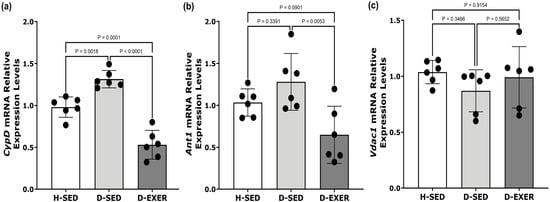

3.3. Effects of Exercise Training and Diabetes on the Expression Levels of CypD, Ant1, and Vdac1 mRNA in the Soleus Skeletal Muscles of Diabetic Rats

As shown in Figure 3, the mRNA expression levels of CypD in skeletal muscle were significantly elevated in the D-SED group by 34.48% (p < 0.004) compared to the H-SED group. In contrast, exercise training in the D-EXER group resulted in a robust, statistically significant reduction in CypD expression compared with both the H-SED and D-SED groups, with decreases of 43.99% and 58.34%, respectively (p < 0.004).

Figure 3.

Effects of exercise on the expression of (a) CypD, (b) Ant1, and (c) Vdac1 mRNA in the soleus muscles of STZ-induced diabetic rats. The mRNA expression levels of each gene were normalized to 18S rRNA levels. Healthy Sedentary (H-SED); Diabetic Sedentary (D-SED); Diabetic Exercise-Trained (D-EXER). The black dots represent individual animal variability. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6 per group). Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.004 after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Differences with p-values between 0.004 and 0.05 are considered suggestive. Cyclophilin D (CypD); adenine nucleotide translocator (Ant1); voltage-dependent anion channel (Vdac1).

Regarding Ant1 expression in skeletal muscle, there were no statistically significant differences between the H-SED and D-SED groups. Although Ant1 expression in the D-EXER group decreased by 46.48% compared with the D-SED group, this change did not reach statistical significance after Bonferroni correction. It should be interpreted as a suggestive trend.

Furthermore, no statistically significant differences in Vdac1 mRNA expression in skeletal muscle were observed among the groups (Figure 3c).

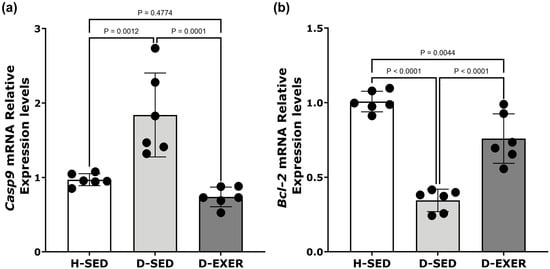

3.4. Impact of Exercise Training and Diabetes on Casp9 and Bcl-2 mRNA Expression in the Soleus Skeletal Muscles of Diabetic Rats

The mRNA expression levels of Casp9 and Bcl-2 in slow-twitch skeletal muscle (soleus) were quantified using RT-qPCR (Figure 4). As shown in Figure 4a, Casp9 mRNA levels were increased by 30.83% in the D-SED group compared to the H-SED group (p = 0.0012); in contrast, Bcl-2 mRNA levels were markedly reduced by 73.39% compared to the H-SED group (p < 0.004), as illustrated in Figure 4b.

Figure 4.

Effects of exercise training on mRNA expression levels of (a) Casp9 and (b) Bcl-2 in skeletal muscle of STZ-induced diabetic rats. The mRNA expression levels for each gene were normalized to 18S rRNA levels. The black dots represent individual animal variability. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) with n = 6 per group. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.004 after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Differences with p-values between 0.004 and 0.05 are considered suggestive. The groups are defined as follows: Healthy Sedentary (H-SED), Diabetic Sedentary (D-SED), and Diabetic Exercise-Trained (D-EXER).

As expected, exercise training resulted in a statistically significant reduction in Casp9 expression in skeletal muscle (Figure 4a) when compared to the D-SED group (p < 0.004). At the same time, Bcl-2 mRNA levels showed a tendency toward an increase when compared to the D-SED group (p = 0.0044) (Figure 4b).

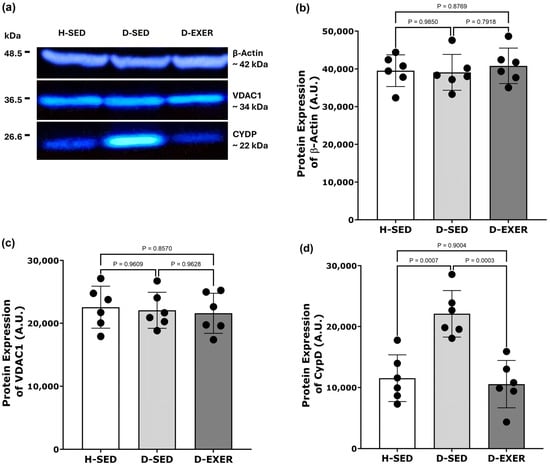

3.5. Effects of Exercise Training and Diabetes on CypD and VDAC1 Expression in the Soleus Skeletal Muscles of Diabetic Rats

In Figure 5, we present the effects of diabetes and exercise training on the expression of CypD and VDAC1 in the soleus muscle. Protein levels were assessed using Western blot analysis (Supplementary Materials), with representative blots shown in Figure 5a and quantitative data displayed in Figure 5b–d. The H-SED, D-SED, and D-EXER groups did not exhibit statistically significant differences in β-actin expression (Figure 5b). Additionally, VDAC1 expression did not differ significantly across all experimental groups (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Effects of exercise training on the protein expression of CypD and VDAC1 in the soleus skeletal muscle of diabetic rats. (a) Representative Western blots show the expression of β-actin (~42 kDa), VDAC1 (~34 kDa), and CypD (~22 kDa) in the following groups: Healthy Sedentary (H-SED), Diabetic Sedentary (D-SED), and Diabetic Exercise-Trained (D-EXER). (b–d) Densitometric analysis of protein levels for (b) β-actin, (c) VDAC1, and (d) CypD is presented. β-actin was used as the loading control. The black dots represent individual animal variability. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6 per group). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.004 after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Differences with p-values between 0.004 and 0.05 are described as suggestive trends.

In contrast, CypD protein expression was markedly higher in the D-SED group than in the H-SED group (p < 0.004), indicating that diabetes is associated with elevated CypD protein levels. Notably, this increase was significantly attenuated in the D-EXER group, with CypD significantly lower than that in the D-SED group (p < 0.004) (Figure 5d).

3.6. Correlation Analysis Between CypD, Ant1, Casp9, and Bcl-2 mRNA Expression Levels and the GSH/GSSG Ratio in the Soleus Skeletal Muscles of Diabetic Rats

To assess whether the changes in mRNA levels of the CypD, Ant1, Bcl-2, and Casp9 genes, induced by exercise training, were correlated with modifications in the GSH/GSSG ratio, we performed correlation analyses comparing mRNA expression levels and GSH/GSSG ratios for each animal in the respective groups (Table 1). The Spearman correlation analysis revealed that Ant1 and Bcl-2 were not associated with the GSH/GSSG ratio across any experimental group (all p-values > 0.05). In contrast, CypD showed a nominally significant and strong inverse correlation with the GSH/GSSG ratio in the D-EXER group (r = −0.8714, p = 0.0428). Similarly, Casp9 showed a strong inverse correlation with the GSH/GSSG ratio in both the H-SED (r = −0.8857, p = 0.0333) and D-EXER (r = −0.9429, p = 0.0167) groups. However, none of these correlations remained statistically significant after correction for multiple comparisons (adjusted significance threshold p < 0.004). In the D-SED group, all correlations were weak to moderate in magnitude and did not reach statistical significance.

Table 1.

Correlation analysis between the GSH/GSSG redox ratio and the expression of mitochondrial regulatory genes (CypD, Ant1, Casp9, and Bcl-2).

4. Discussion

Exercise training is widely recognized as a non-pharmacological approach to improving metabolic health in several tissues, particularly in the context of metabolic diseases such as diabetes [60,61]. However, the molecular changes induced by exercise in diabetic skeletal muscle remain insufficiently characterized. Alterations in the expression of mPTP-related components have been associated with oxidative stress, hyperglycemia, and dysregulated apoptosis, all of which are characteristic features of diabetes [14].

The present study provides evidence suggesting that a moderate-intensity aerobic exercise training program may reduce oxidative stress and modulate the gene expression of CypD, Ant1, Bcl-2, and Casp9 in the soleus muscle of diabetic rats. These observations contribute to the growing body of literature exploring the mechanisms through which moderate-intensity exercise exerts beneficial metabolic effects in the skeletal muscle of diabetic animals.

STZ effectively induces a diabetic rat model characterized by insulin deficiency and hyperglycemia, as demonstrated in this study. STZ achieves this by destroying pancreatic beta cells, which produce insulin [62,63]. Moreover, STZ-induced diabetic rats exhibited a significant reduction in body weight compared to control rats [64]. Hyperglycemia is linked to unintentional weight loss due to the physiological changes it triggers, including increased lipolysis and proteolysis in response to the body’s inability to use glucose for energy, leading to muscle loss [60]. In light of this, studies have shown that regular aerobic exercise in diabetic rats can significantly improve metabolic parameters and reduce diabetes-related complications [65]. However, the impact of exercise on hyperglycemia and weight may vary depending on the type and intensity of exercise, as well as the duration and severity of diabetes [66,67]. In the present study, eight weeks of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise were associated with lower blood glucose levels in diabetic rats. However, no notable differences in body weight gain were observed between the trained and untrained diabetic groups. The improvement in glucose metabolism is a hallmark adaptation of exercise [68]. This is consistent with Khaledi et al. [69], who demonstrated improvements in insulin sensitivity and blood glucose regulation after eight weeks of aerobic training in type 2 diabetic rats.

The onset, progression, and complications of diabetes are widely recognized to be influenced by excessive ROS production and increased oxidative stress [70]. Prior studies from our group have demonstrated that oxidative stress contributes significantly to the development of diabetes-induced skeletal muscle dysfunction, primarily due to oxidative damage to essential cellular components, including lipids, proteins, and DNA [71,72].

Hyperglycemia is commonly linked to increased levels of free radicals and reduced antioxidant defenses [73]. One important non-enzymatic antioxidant in skeletal muscle is GSH, which plays a critical role in both antioxidant protection and muscle function [74]. The current research showed elevated ROS levels and decreased total glutathione levels, along with a lower GSH/GSSG ratio, in the soleus muscle of diabetic rats. These results are consistent with a state of cellular redox imbalance [71], a hallmark of oxidative stress commonly observed in diabetes-related complications [73,75].

However, exercise training has been found to enhance antioxidant defense mechanisms in various tissues affected by metabolic disorders [76]. In this study, AET was associated with lower ROS levels and an improved glutathione redox state. This effect is generally favorable, as it suggests increased antioxidant capacity and decreased oxidative stress [44,77]. Our findings are consistent with previous studies that report similar outcomes [76,78,79].

In pathological conditions, excessive ROS production can alter the cells’ transcriptome, either promoting survival mechanisms to cope with stress or triggering cell death, depending on the severity and duration of the imbalance [80]. In diabetes, ROS-induced oxidative damage can affect mitochondrial genes and proteins, particularly those involved in calcium and protein transport, which are differentially expressed in diabetic complications [81,82]. In the present study, STZ-induced diabetes was associated with increased CypD protein expression and mRNA levels in the soleus muscle. In contrast, VDAC1 protein and mRNA levels remained unchanged across all groups, suggesting that diabetes preferentially affects CypD expression without altering VDAC1 levels.

CypD, ANT1, and VDAC1 are among the proteins involved in the formation and regulation of the mPTP [83,84,85]. Although the functional evaluation of the mPTP and the role of these proteins in skeletal muscle fibers of diabetic rats have not been extensively studied, several investigations suggest that this multiprotein complex undergoes significant changes in the diabetic state, leading to an increased susceptibility to pore opening [14,31]. Consistent with our findings in skeletal muscle, mitochondria in diabetic hearts exhibit increased CypD expression, which has been linked to heightened mPTP sensitivity and mitochondrial dysfunction [31]. Furthermore, the implications of ANT1 expression, as measured by mRNA levels in diabetic muscle, remain poorly understood. The present data suggest that diabetes may influence ANT1 transcript levels in skeletal muscle, underscoring the need for further research.

Our observations indicate that, although only a few studies have explored this issue, several suggest that changes in the mPTP associated with diabetes are primarily due to alterations in CypD expression. For instance, increased CypD expression has been observed in the brains of STZ-induced diabetic mice and in the temporal cortices of individuals with diabetes, highlighting the potential clinical significance of CypD in the development of diabetes-related neurodegeneration [86].

Additionally, another study found that serum CypD levels are elevated in patients with type 2 diabetes, especially in those with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, indicating a possible connection between CypD and the progression of diabetic complications [87]. Furthermore, CypD has been linked to reduced insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle [29]. In this context, reduced CypD expression is associated with protection against various aspects of diabetes, including pancreatic β-cell death in models of glucotoxicity [88] and kidney injury in diabetic mice [28].

On the other hand, studies indicate that inhibiting CypD, either through mutations or pharmacologically with cyclosporine A, prevents mPTP formation [22,89]. This prevention may help avoid the release of pro-apoptotic molecules that initiate the intrinsic apoptosis pathway [90,91]. To investigate this further, we analyzed the expression levels of the genes Casp9 and Bcl-2. Our results show that Casp9 expression, which is the initiator of the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway [92], was higher in the D-SED group compared to the H-SED group. These findings align with previous studies [31,91,92].

Additionally, we observed reduced Bcl-2 expression in the D-SED group; Bcl-2 is known to regulate apoptosis [93]. This observation is also consistent with earlier research [31,94]. Interestingly, our results indicate that exercise training was associated with modulation of CypD at both the transcript and protein levels, as well as of the pro-apoptotic gene Casp9 and the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2. In diabetes, the effects of exercise training have included increased Bcl-2 gene expression and decreased expression of genes such as Bax and Casp9 across various tissues, including the heart [95] and pancreatic beta cells [96]. To our knowledge, the present findings extend these observations to skeletal muscle in the context of diabetes. An important issue raised by these findings concerns the temporal relationship between ROS reduction and changes in gene expression, particularly whether shifts in oxidative status precede transcriptional modulation. Clarifying this sequence is essential for interpreting the mechanistic significance of the results, given that aerobic exercise concurrently affects redox balance [97], mitochondrial function [98], and apoptotic signaling [99]. However, the temporal order of these adaptations remains unresolved.

Therefore, in this study, correlation analysis was conducted to assess whether exercise-induced changes in mRNA levels are associated with improvements in oxidative status. The results indicated that alterations in CypD and Casp9 transcript levels were associated with increased GSH/GSSG ratios. However, these associations did not remain statistically significant after correction for multiple comparisons and should therefore be interpreted cautiously. No similar relationship was found for the other genes within the D+EXER group. One interpretation of these findings is that early reductions in ROS and the restoration of a more favorable redox state may precede transcriptional modulation, particularly for genes regulated by redox-sensitive pathways. In this scenario, an elevated GSH/GSSG ratio could create conditions that enhance the modulation of CypD and Casp9. This aligns with the notion that exercise-induced antioxidant adaptations may affect transcriptional programs related to mitochondrial integrity and cell survival [99].

On the other hand, the absence of correlations for other genes suggests that exercise-sensitive transcripts differ in their responsiveness to oxidative fluctuations. Therefore, CypD and Casp9 may represent a specific subset of genes whose expression is more closely linked to redox dynamics.

This preclinical investigation in diabetic animals provides mechanistic insight into the molecular mechanisms of diabetes and its complications, supports evaluating the therapeutic effects of exercise, highlights potential molecular targets, and offers experimental evidence relevant to clinical recommendations for exercise as a primary intervention.

Limitations

It is essential to acknowledge the inherent limitations of this study, which is vital for a comprehensive understanding of the findings presented in this manuscript. Firstly, our investigation lacks direct measurements of mPTP opening and overall mitochondrial permeability. The inclusion of complementary functional assays, such as calcium retention capacity or mitochondrial swelling, would provide direct evidence of mitochondrial function across physiological and pathological conditions (e.g., oxidative stress, disease states) and for screening pharmacological agents that inhibit or promote mPTP opening [100,101]. The absence of these measurements limits the ability to directly confirm mPTP functional modulation and constrains interpretation to molecular and biochemical markers.

In addition, the interpretation of the potential anti-apoptotic effects of exercise training is limited by the absence of direct protein-level or functional apoptosis assays. Incorporating techniques such as TUNEL staining or caspase activity measurements would allow a more direct assessment of apoptotic signaling and cell fate [102]. Therefore, conclusions regarding apoptosis-related mechanisms should be interpreted with caution.

Another significant limitation is that this study was conducted solely with male rats. This is particularly noteworthy, as males and females exhibit marked differences in muscle physiology and exercise-induced adaptive responses, including variations in mitochondrial adaptations [103]. These differences can be influenced by a range of factors, including sex hormones, genetic background, and metabolic processes [104,105]. Consequently, the extent to which the present findings can be generalized to female animals remains to be established.

Additionally, the relatively small sample size, while consistent with ethical considerations and exploratory mechanistic research, limits the statistical power to detect small or moderate effects. Thus, some observed associations should be interpreted as suggestive and need confirmation in a much larger study.

Despite these limitations, the findings provide a mechanistic framework for future research and enhance our understanding of how AET affects metabolism and the adaptive responses of skeletal muscle in diabetes. Importantly, the present results support the rationale for future studies employing larger sample sizes, direct functional assays, and sex-comparative designs to further clarify causal relationships.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the current research demonstrated that 8-week AET reduces hyperglycemia and attenuates oxidative stress in diabetic skeletal muscle by lowering ROS production and improving redox status by increasing GSH levels. Moreover, the findings support a potential role for skeletal muscle’s response to AET through modulation of mPTP-related molecular markers under diabetic conditions. In this context, one notable observation of this study was a strong inverse correlation between the mRNA levels of CypD and Casp9 with the enhanced glutathione redox state.

Nevertheless, further investigation is required to clarify the temporal sequence and functional significance of these molecular adaptations and to elucidate the biological networks underlying skeletal muscle responses in diabetic conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/diabetology7010018/s1, Figure S1: Uncropped β-actin blot. The membrane includes lanes from two independent experimental protocols. Lanes corresponding to the EXERT-LOW condition were generated as part of a separate experimental protocol and were not analyzed in the present study. Only the indicated lanes were used for densitometric analysis and data quantification in this manuscript.; Figure S2: Uncropped Western blot for VDAC1 and CypD. Representative full-length membranes showing sequential immunodetection of VDAC1 (upper bands) and CypD (lower bands) on the same membrane using antibodies applied at different times. Lane corresponds to H-SED, D-SED, and D-EXERT groups loaded. Each lane was used for densitometric quantifications shown in the corresponding graphs.

Author Contributions

L.A.S.-B.: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, visualization, and writing—original draft. S.S.-D.: formal analysis and investigation. M.G.V.-D.: methodology and resources. S.M.-G.: investigation, funding acquisition, and resources. K.S.V.-D.: investigation, funding acquisition, and resources. R.M.-P.: funding acquisition, supervision, and resources. C.C.-C.: investigation, funding acquisition, and resources. E.S.-D.: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, project administration, validation, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Coordinación de Investigación Científica, Universidad de Guanajuato (CIIC-011/2023).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Comité de Ética para la Investigación de la Universidad de Guanajuato (CEPIUG), under registration number CEPIUG-P26-2023 (Approval date: 1 August 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| mPTP | Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore |

| AET | Aerobic Exercise Training |

| STZ | Streptozotocin |

| H-SED | Healthy Sedentary |

| D-SED | Diabetic Sedentary |

| D-EXER | Diabetic Exercise Trained |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| VDAC | Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel |

| ANT | Adenine Nucleotide Translocator |

| CypD | Cyclophilin D |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| CEPIUG | Comité de Ética para la Investigación de la Universidad de Guanajuato (Ethics Committee for Research at the University of Guanajuato) |

| FBG | Fasting blood glucose |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| VO2max | Maximum Volume of Oxygen |

| H2DCFDA | 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate |

| GSH | Reduced glutathione |

| GSSG | Oxidized glutathione |

References

- Antar, S.A.; Ashour, N.A.; Sharaky, M.; Khattab, M.; Ashour, N.A.; Zaid, R.T.; Roh, E.J.; Elkamhawy, A.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A. Diabetes Mellitus: Classification, Mediators, and Complications; A Gate to Identify Potential Targets for the Development of New Effective Treatments. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheagwam, F.N.; Iheagwam, O.T. Diabetes Mellitus: The Pathophysiology as a Canvas for Management Elucidation and Strategies. Med. Nov. Technol. Devices 2025, 25, 100351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, B.B.; Magliano, D.J.; Boyko, E.J. IDF Diabetes Atlas 11th edition 2025: Global prevalence and projections for 2050. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2025, 41, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, M.; Khathi, A. Prediabetes-Associated Changes in Skeletal Muscle Function and Their Possible Links with Diabetes: A Literature Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, O.; Jorge, J. Diabetes and Sarcopenia: Unraveling the Metabolic Crossroads of Muscle Loss and Glycemic Dysregulation. Endocrines 2025, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Pedrosa, J.M.; Camprubi-Robles, M.; Guzman-Rolo, G.; Lopez-Gonzalez, A.; Garcia-Almeida, J.M.; Sanz-Paris, A.; Rueda, R. The Vicious Cycle of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Skeletal Muscle Atrophy: Clinical, Biochemical, and Nutritional Bases. Nutrients 2024, 16, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino-Gonzalez, E.; Dalbram, E.; Mounier, R.; Gondin, J.; Farup, J.; Jessen, N.; Treebak, J.T. Impaired Skeletal Muscle Regeneration in Diabetes: From Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms to Novel Treatments. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 1204–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, Q.; Zhao, D.; Lian, F.; Li, X.; Qi, W. The Impact of Oxidative Stress-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction on Diabetic Microvascular Complications. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1112363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieczenik, S.R.; Neustadt, J. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Molecular Pathways of Disease. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2007, 83, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, D.E.; He, J.; Menshikova, E.V.; Ritov, V.B. Dysfunction of Mitochondria in Human Skeletal Muscle in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2002, 51, 2944–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimaki, S.; Kuwabara, T. Diabetes-Induced Dysfunction of Mitochondria and Stem Cells in Skeletal Muscle and the Nervous System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheagwam, F.N.; Joseph, A.J.; Adedoyin, E.D.; Iheagwam, O.T.; Ejoh, S.A. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Diabetes: Shedding Light on a Widespread Oversight. Pathophysiology 2025, 32, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrauwen-Hinderling, V.B.; Kooi, M.E.; Schrauwen, P. Mitochondrial Function and Diabetes: Consequences for Skeletal and Cardiac Muscle Metabolism. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2016, 24, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belosludtsev, K.N.; Belosludtseva, N.V.; Dubinin, M.V. Diabetes Mellitus, Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Ca2+-Dependent Permeability Transition Pore. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Li, H.; Liao, P.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Zheng, M.; Gao, J. Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Mechanisms and Advances in Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, P.; Gerle, C.; Halestrap, A.P.; Jonas, E.A.; Karch, J.; Mnatsakanyan, N.; Pavlov, E.; Sheu, S.-S.; Soukas, A.A. Identity, Structure, and Function of the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore: Controversies, Consensus, Recent Advances, and Future Directions. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 1869–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briston, T.; Selwood, D.L.; Szabadkai, G.; Duchen, M.R. Mitochondrial Permeability Transition: A Molecular Lesion with Multiple Drug Targets. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 40, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, R.J.; Murphy, E.; Liu, J.C. Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore and Calcium Handling. In Mitochondrial Bioenergetics; Palmeira, C.M., Moreno, A.J., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1782, pp. 187–196. ISBN 978-1-4939-7830-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bonora, M.; Bononi, A.; De Marchi, E.; Giorgi, C.; Lebiedzinska, M.; Marchi, S.; Patergnani, S.; Rimessi, A.; Suski, J.M.; Wojtala, A.; et al. Role of the c Subunit of the FO ATP Synthase in Mitochondrial Permeability Transition. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Mohammed Al-Amily, I.; Mohammed, S.; Luan, C.; Asplund, O.; Ahmed, M.; Ye, Y.; Ben-Hail, D.; Soni, A.; Vishnu, N.; et al. Preserving Insulin Secretion in Diabetes by Inhibiting VDAC1 Overexpression and Surface Translocation in β Cells. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 64–77.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgio, V.; Guo, L.; Bassot, C.; Petronilli, V.; Bernardi, P. Calcium and Regulation of the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition. Cell Calcium 2018, 70, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karch, J.; Bround, M.J.; Khalil, H.; Sargent, M.A.; Latchman, N.; Terada, N.; Peixoto, P.M.; Molkentin, J.D. Inhibition of Mitochondrial Permeability Transition by Deletion of the ANT Family and CypD. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinke, G.; Zhou, L.; Sazanov, L.A. Cryo-EM Structure of the Entire Mammalian F-Type ATP Synthase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrer, A.; Tommasin, L.; Šileikytė, J.; Ciscato, F.; Filadi, R.; Urbani, A.; Forte, M.; Rasola, A.; Szabò, I.; Carraro, M.; et al. Defining the Molecular Mechanisms of the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition through Genetic Manipulation of F-ATP Synthase. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubaidi, F.F.; Zainalabidin, S.; Mariappan, V.; Budin, S.B. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: The Possible Therapeutic Roles of Phenolic Acids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caturano, A.; Rocco, M.; Tagliaferri, G.; Piacevole, A.; Nilo, D.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Iadicicco, I.; Donnarumma, M.; Galiero, R.; Acierno, C.; et al. Oxidative Stress and Cardiovascular Complications in Type 2 Diabetes: From Pathophysiology to Lifestyle Modifications. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, R.C.; Moukdar, F.; Frasier, C.R.; Patel, H.D.; Bostian, P.A.; Lust, R.M.; Brown, D.A. Mitochondrial Permeability Transition in the Diabetic Heart: Contributions of Thiol Redox State and Mitochondrial Calcium to Augmented Reperfusion Injury. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2012, 52, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblom, R.S.J.; Higgins, G.C.; Nguyen, T.-V.; Arnstein, M.; Henstridge, D.C.; Granata, C.; Snelson, M.; Thallas-Bonke, V.; Cooper, M.E.; Forbes, J.M.; et al. Delineating a Role for the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore in Diabetic Kidney Disease by Targeting Cyclophilin D. Clin. Sci. 2020, 134, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddeo, E.P.; Laker, R.C.; Breen, D.S.; Akhtar, Y.N.; Kenwood, B.M.; Liao, J.A.; Zhang, M.; Fazakerley, D.J.; Tomsig, J.L.; Harris, T.E.; et al. Opening of the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore Links Mitochondrial Dysfunction to Insulin Resistance in Skeletal Muscle. Mol. Metab. 2013, 3, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.J.; Seiça, R.; Coxito, P.M.; Rolo, A.P.; Palmeira, C.M.; Santos, M.S.; Moreno, A.J.M. Enhanced Permeability Transition Explains the Reduced Calcium Uptake in Cardiac Mitochondria from Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. FEBS Lett. 2003, 554, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, C.L.; Dabkowski, E.R.; Baseler, W.A.; Croston, T.L.; Alway, S.E.; Hollander, J.M. Enhanced Apoptotic Propensity in Diabetic Cardiac Mitochondria: Influence of Subcellular Spatial Location. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010, 298, H633–H642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monaco, C.M.F.; Hughes, M.C.; Ramos, S.V.; Varah, N.E.; Lamberz, C.; Rahman, F.A.; McGlory, C.; Tarnopolsky, M.A.; Krause, M.P.; Laham, R.; et al. Altered Mitochondrial Bioenergetics and Ultrastructure in the Skeletal Muscle of Young Adults with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 1411–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.A.B.; Murach, K.A.; Dyar, K.A.; Zierath, J.R. Exercise Metabolism and Adaptation in Skeletal Muscle. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 607–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendlinger, M.; Mastrototaro, L.; Exterkate, M.; Apostolopoulou, M.; Karusheva, Y.; Heilmann, G.; Lipaeva, P.; Straßburger, K.; Gancheva, S.; Kahl, S.; et al. Exercise Training Increases Skeletal Muscle Sphingomyelinases and Affects Mitochondrial Quality Control in Men with Type 2 Diabetes. Metabolism 2025, 172, 156361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, L.; Knight, E.; Broderick, T.L.; Al-Nakkash, L.; Tobin, B.; Geetha, T.; Babu, J.R. Moderate-Intensity Exercise Enhances Mitochondrial Biogenesis Markers in the Skeletal Muscle of a Mouse Model Affected by Diet-Induced Obesity. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.R.; Seo, D.Y.; Park, S.H.; Kwak, H.B.; Kim, M.; Ko, K.S.; Rhee, B.D.; Han, J. Aerobic Exercise Training Decreases Cereblon and Increases AMPK Signaling in the Skeletal Muscle of STZ-Induced Diabetic Rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 501, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peifer-Weiß, L.; Al-Hasani, H.; Chadt, A. AMPK and Beyond: The Signaling Network Controlling RabGAPs and Contraction-Mediated Glucose Uptake in Skeletal Muscle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.-W.; Yoo, S.-Z.; No, M.-H.; Park, D.-H.; Kang, J.-H.; Kim, T.-W.; Kim, C.-J.; Seo, D.-Y.; Han, J.; Yoon, J.-H.; et al. Exercise Training Attenuates Obesity-Induced Skeletal Muscle Remodeling and Mitochondria-Mediated Apoptosis in the Skeletal Muscle. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, F.; Zhao, X.; You, J.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yu, L.; Li, J.; et al. Aerobic Exercise Alleviates Skeletal Muscle Aging in Male Rats by Inhibiting Apoptosis via Regulation of the Trx System. Exp. Gerontol. 2024, 194, 112523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumini-Oliveira, J.; Magalhães, J.; Pereira, C.V.; Moreira, A.C.; Oliveira, P.J.; Ascensão, A. Endurance Training Reverts Heart Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Permeability Transition and Apoptotic Signaling in Long-Term Severe Hyperglycemia. Mitochondrion 2011, 11, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE Guidelines 2.0: Updated Guidelines for Reporting Animal Research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Aluja, A.S. Animales de laboratorio y la Norma Oficial Mexicana (NOM-062-ZOO-1999). Gac Med Mex. 2002, 138, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Díaz, L.; Zambrano, E.; Flores, M.E.; Contreras, M.; Crispín, J.C.; Alemán, G.; Bravo, C.; Armenta, A.; Valdés, V.J.; Tovar, A.; et al. Ethical Considerations in Animal Research: The Principle of 3R’s. Rev. Investig. Clin. 2020, 73, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Duarte, S.; Márquez-Gamiño, S.; Montoya-Pérez, R.; Villicaña-Gómez, E.A.; Vera-Delgado, K.S.; Caudillo-Cisneros, C.; Sotelo-Barroso, F.; Melchor-Moreno, M.T.; Sánchez-Duarte, E. Nicorandil Decreases Oxidative Stress in Slow- and Fast-Twitch Muscle Fibers of Diabetic Rats by Improving the Glutathione System Functioning. J. Diabetes Investig. 2021, 12, 1152–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoyagi, A.; Ishikura, K.; Nabekura, Y. Exercise Intensity during Olympic-Distance Triathlon in Well-Trained Age-Group Athletes: An Observational Study. Sports 2021, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Soya, H.; Murakumo, K.; Araki, Y.; Hiraga, T.; Soya, S.; Okamoto, M. Setting Treadmill Intensity for Rat Aerobic Training Using Lactate and Gas Exchange Thresholds. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2025, 57, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høydal, M.A.; Wisløff, U.; Kemi, O.J.; Ellingsen, O. Running Speed and Maximal Oxygen Uptake in Rats and Mice: Practical Implications for Exercise Training. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 2007, 14, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, F.; Dong, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, M.; Wang, Z.; Qu, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, J. Maximum Oxygen Consumption and Quantification of Exercise Intensity in Untrained Male Wistar Rats. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadaei Chafy, M.R.; Bagherpour Tabalvandani, M.M.; Elmieh, A.; Arabzadeh, E. Determining the Range of Aerobic Exercise on a Treadmill for Male Wistar Rats at Different Ages: A Pilot Study. J. Exerc. Organ Cross Talk 2022, 2, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahputra, M.; Lindarto, D.; Ramayani, O.R.; Machrina, Y.; Purba, A.; Putra, I.B.; Nasution, I.P.A.; Harahap, J. Effect of Moderate Intensity Continuous Training and Slow Type Interval Training to Gene Expression of TGF-β in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Model Wistar Rats. Med. Arch. 2023, 77, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati-Ahmadabad, S.; Rostamkhani, F.; Meftahi, G.H.; Shirvani, H. Comparative Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training and Moderate-Intensity Continuous Training on Soleus Muscle Fibronectin Type III Domain-Containing Protein 5, Myonectin and Glucose Transporter Type 4 Gene Expressions: A Study on the Diabetic Rat Model. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 6123–6129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabzadeh, E.; Shirvani, H.; Ebadi Zahmatkesh, M.; Riyahi Malayeri, S.; Meftahi, G.H.; Rostamkhani, F. Irisin/FNDC5 Influences Myogenic Markers on Skeletal Muscle Following High and Moderate-Intensity Exercise Training in STZ-Diabetic Rats. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo-Sánchez, E.; Peña-Montes, D.; Sánchez-Duarte, S.; Saavedra-Molina, A.; Sánchez-Duarte, E.; Montoya-Pérez, R. Effects of Apocynin on Heart Muscle Oxidative Stress of Rats with Experimental Diabetes: Implications for Mitochondria. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Kode, A.; Biswas, S.K. Assay for Quantitative Determination of Glutathione and Glutathione Disulfide Levels Using Enzymatic Recycling Method. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 3159–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomczynski, P.; Sacchi, N. Single-Step Method of RNA Isolation by Acid Guanidinium Thiocyanate-Phenol-Chloroform Extraction. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 162, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, J.; Wilkinson, D.; Rankin, D.; Phillips, B.; Szewczyk, N.; Smith, K.; Atherton, P. An Overview of Technical Considerations for Western Blotting Applications to Physiological Research. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2017, 27, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soderstrom, C.I.; Larsen, J.; Owen, C.; Gifondorwa, D.; Beidler, D.; Yong, F.H.; Conrad, P.; Neubert, H.; Moore, S.A.; Hassanein, M. Development and Validation of a Western Blot Method to Quantify Mini-Dystrophin in Human Skeletal Muscle Biopsies. AAPS J. 2022, 25, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyfault, J.P.; Bergouignan, A. Exercise and Metabolic Health: Beyond Skeletal Muscle. Diabetologia 2020, 63, 1464–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg Sibony, R.; Segev, O.; Dor, S.; Raz, I. Overview of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Diabetes. J. Diabetes 2024, 16, e70014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi, A.; Jeddi, S. Streptozotocin as a Tool for Induction of Rat Models of Diabetes: A Practical Guide. EXCLI J. 2023, 22, 274–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yan, L.-J. Streptozotocin-Induced Type 1 Diabetes in Rodents as a Model for Studying Mitochondrial Mechanisms of Diabetic β Cell Glucotoxicity. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2015, 8, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Boyle, K.E.; Broderick, T.L. The Effects of Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes and Insulin Treatment on Carnitine Biosynthesis and Renal Excretion. Molecules 2021, 26, 6872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaat, M.A.; Choobdari, H.R.; Sheykhlouvand, M. Cardioprotective Effects of Aerobic Training in Diabetic Rats: Reducing Cardiac Apoptotic Indices and Oxidative Stress for a Healthier Heart. ARYA Atheroscler. 2024, 20, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahalka, S.J.; Abushamat, L.A.; Scalzo, R.L.; Reusch, J.E.B. The Role of Exercise in Diabetes. In Endotext; Feingold, K.R., Ahmed, S.F., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M.R., Boyce, A., Chrousos, G., Corpas, E., de Herder, W.W., Dhatariya, K., Dungan, K., et al., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Syeda, U.S.A.; Battillo, D.; Visaria, A.; Malin, S.K. The Importance of Exercise for Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes. Am. J. Med. Open 2023, 9, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteves, J.V.; Stanford, K.I. Exercise as a Tool to Mitigate Metabolic Disease. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2024, 327, C587–C598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaledi, K.; Hoseini, R.; Gharzi, A. Effects of Aerobic Training and Vitamin D Supplementation on Glycemic Indices and Adipose Tissue Gene Expression in Type 2 Diabetic Rats. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xie, N.; Feng, L.; Huang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Y. Oxidative Stress in Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications: From Pathophysiology to Therapeutic Strategies. Chin. Med. J. 2025, 138, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Duarte, S.; Montoya-Pérez, R.; Márquez-Gamiño, S.; Vera-Delgado, K.S.; Caudillo-Cisneros, C.; Sotelo-Barroso, F.; Sánchez-Briones, L.A.; Sánchez-Duarte, E. Apocynin Attenuates Diabetes-Induced Skeletal Muscle Dysfunction by Mitigating ROS Generation and Boosting Antioxidant Defenses in Fast-Twitch and Slow-Twitch Muscles. Life 2022, 12, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Duarte, S.; Sánchez-Duarte, E.; Sánchez-Briones, L.A.; Meléndez-Herrera, E.; Herrera-Vargas, M.A.; Márquez-Gamiño, S.; Vera-Delgado, K.S.; Montoya-Pérez, R. Apocynin Mitigates Diabetic Muscle Atrophy by Lowering Muscle Triglycerides and Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, P.; Lozano, P.; Ros, G.; Solano, F. Hyperglycemia and Oxidative Stress: An Integral, Updated and Critical Overview of Their Metabolic Interconnections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, S.; Ciccarone, F.; Limongi, D.; Checconi, P.; Palamara, A.T.; Ciriolo, M.R. Glutathione and Nitric Oxide: Key Team Players in Use and Disuse of Skeletal Muscle. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawi, J.; Misakyan, Y.; Affa, S.; Kades, S.; Narasimhan, A.; Hajjar, F.; Besser, M.; Tumanyan, K.; Venketaraman, V. Oxidative Stress, Glutathione Insufficiency, and Inflammatory Pathways in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Implications for Therapeutic Interventions. Biomedicines 2024, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Howarth, F.C.; Raza, H. Exercise Alleviates Diabetic Complications by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress-Mediated Signaling Cascade and Mitochondrial Metabolic Stress in GK Diabetic Rat Tissues. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1052608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, Y.; Kizaki, M.; Nakagiri, R.; Kamiya, T.; Sumi, H.; Osawa, T. Dietary Glutathione Protects Rats from Diabetic Nephropathy and Neuropathy. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 897–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifi-skishahr, F.; Damirchi, A.; Farjaminezhad, M.; Babaei, P. Physical Training Status Determines Oxidative Stress and Redox Changes in Response to an Acute Aerobic Exercise. Biochem. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 3757623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gül, M.; Atalay, M.; Hänninen, O. Endurance Training and Glutathione-Dependent Antioxidant Defense Mechanism in Heart of the Diabetic Rats. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2003, 2, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Boiti, A.; Vallone, D.; Foulkes, N.S. Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling and Oxidative Stress: Transcriptional Regulation and Evolution. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, D.; Mei, Z.; Deng, Y. Mitochondrial Quality Control in Diabetes Mellitus and Complications: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, A.B.; Kampmann, U.; Hedegaard, J.; Thorsen, K.; Nordentoft, I.; Vendelbo, M.H.; Møller, N.; Jessen, N. Altered Gene Expression and Repressed Markers of Autophagy in Skeletal Muscle of Insulin Resistant Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, M.; Virji, S.; Ward, J.M. Cyclophilin-D Binds Strongly to Complexes of the Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel and the Adenine Nucleotide Translocase to Form the Permeability Transition Pore. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998, 258, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, C.P.; Kaiser, R.A.; Purcell, N.H.; Blair, N.S.; Osinska, H.; Hambleton, M.A.; Brunskill, E.W.; Sayen, M.R.; Gottlieb, R.A.; Dorn, G.W.; et al. Loss of Cyclophilin D Reveals a Critical Role for Mitochondrial Permeability Transition in Cell Death. Nature 2005, 434, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, J.Q.; Molkentin, J.D. Physiological and Pathological Roles of the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore in the Heart. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Du, F.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhong, C.; Yu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Lue, L.-F.; Walker, D.G.; Douglas, J.T.; et al. F1F0 ATP Synthase–Cyclophilin D Interaction Contributes to Diabetes-Induced Synaptic Dysfunction and Cognitive Decline. Diabetes 2016, 65, 3482–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naguib, M.; Abou Elfotouh, M.; Wifi, M.-N. Elevated Serum Cyclophilin D Level Is Associated with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Higher Fibrosis Scores in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 4665–4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Jin, X.; Cai, H.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, X. PDZD8 Augments Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondria Contact and Regulates Ca2+ Dynamics and Cypd Expression to Induce Pancreatic β-Cell Death during Diabetes. Diabetes Metab. J. 2024, 48, 1058–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbani, A.; Giorgio, V.; Carrer, A.; Franchin, C.; Arrigoni, G.; Jiko, C.; Abe, K.; Maeda, S.; Shinzawa-Itoh, K.; Bogers, J.F.M.; et al. Purified F-ATP Synthase Forms a Ca2+-Dependent High-Conductance Channel Matching the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonora, M.; Wieckowsk, M.R.; Chinopoulos, C.; Kepp, O.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L.; Pinton, P. Erratum: Molecular Mechanisms of Cell Death: Central Implication of ATP Synthase in Mitochondrial Permeability Transition. Oncogene 2015, 34, 1475–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.M.; Murphy, E. Role of Mitochondrial Calcium and the Permeability Transition Pore in Regulating Cell Death. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, L.; Li, W.; Wang, G.; Guo, L.; Jiang, Y.; Kang, Y.J. Hyperglycemia-Induced Apoptosis in Mouse Myocardium: Mitochondrial cytochrome C-mediated caspase-3 activation pathway. Diabetes 2002, 51, 1938–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirino-Galindo, G.; Hernández-Hernández, D.E.; Reyes-Mateos, L.C.; Mejía-Zepeda, R.; Martínez-García, M.; Palomar-Morales, M. Bcl-2 Expression in a Diabetic Embryopathy Model in Presence of Polyamines. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.-Anim. 2019, 55, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velmurugan, G.V.; White, C. Calcium Homeostasis in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Is Altered in Type 2 Diabetes by Bcl-2 Protein Modulation of InsP3R Calcium Release Channels. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012, 302, H124–H134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibi, P.; Alihemmati, A.; Ahmadiasl, N.; Fateh, A.; Anvari, E. Exercise Training Attenuates Diabetes-Induced Cardiac Injury through Increasing miR-133a and Improving pro-Apoptosis/Anti-Apoptosis Balance in Ovariectomized Rats. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2020, 23, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wei, Y.; Wang, C. Impacts of an Exercise Intervention on the Health of Pancreatic Beta-Cells: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.K.; Schrager, M. Redox Signaling Regulates Skeletal Muscle Remodeling in Response to Exercise and Prolonged Inactivity. Redox Biol. 2022, 54, 102374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Jiang, D.-M.; Yu, R.-R.; Zhang, L.-L.; Liu, Y.-Z.; Chen, J.-X.; Chen, H.-C.; Liu, Y.-P. The Effect of Aerobic Exercise on the Oxidative Capacity of Skeletal Muscle Mitochondria in Mice with Impaired Glucose Tolerance. J. Diabetes Res. 2022, 2022, 3780156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Baker, J.S.; Davison, G.W.; Yan, X. Redox Signaling and Skeletal Muscle Adaptation during Aerobic Exercise. iScience 2024, 27, 109643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Huang, J.; Hu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Cao, Z.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Feng, H.; Wang, J.; et al. Detection Assays of Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore: Current Status and Future Prospects. Acta Histochem. 2025, 127, 152278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endlicher, R.; Drahota, Z.; Štefková, K.; Červinková, Z.; Kučera, O. The Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore-Current Knowledge of Its Structure, Function, and Regulation, and Optimized Methods for Evaluating Its Functional State. Cells 2023, 12, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzayans, R.; Murray, D. Do TUNEL and Other Apoptosis Assays Detect Cell Death in Preclinical Studies? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalanza, J.F.; Sanchez-Roige, S.; Cigarroa, I.; Gagliano, H.; Fuentes, S.; Armario, A.; Capdevila, L.; Escorihuela, R.M. Long-Term Moderate Treadmill Exercise Promotes Stress-Coping Strategies in Male and Female Rats. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landen, S.; Voisin, S.; Craig, J.M.; McGee, S.L.; Lamon, S.; Eynon, N. Genetic and Epigenetic Sex-Specific Adaptations to Endurance Exercise. Epigenetics 2019, 14, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Gorman, S.A.; Miller, C.T.; Rawstorn, J.C.; Sabag, A.; Sultana, R.N.; Lanting, S.M.; Keating, S.E.; Johnson, N.A.; Way, K.L. Sex Differences in the Feasibility of Aerobic Exercise Training for Improving Cardiometabolic Health Outcomes in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.