Abstract

The urgent need for effective therapies against cancer and antimicrobial-resistant pathogens motivates the development of novel metal-based complexes. Herein, we report the synthesis and characterization of four novel cobalt(II) complexes with biologically relevant β-diketo ester ligands. The complexes were characterized via UV-Vis, FTIR, mass spectrometry, and elemental analysis. Their biological activities were evaluated through antimicrobial and cytotoxic assays. Complex B1 exhibited the strongest antimicrobial activity, with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 0.23 mg/mL against Staphylococcus aureus and Proteus mirabilis, and 0.01 mg/mL against Mucor mucedo, exceeding the performance of ketoconazole. Cytotoxicity studies on SW480 colorectal cancer cells and HaCaT normal keratinocytes identified B3 as the most potent anticancer agent (IC50 = 11.49 µM), selectively targeting tumor cells. Morphological analysis indicated apoptosis as the primary mode of cell death. Mechanistic studies were performed to elucidate interactions with biomolecules. UV-Vis and fluorescence spectroscopy, viscosity measurements, and molecular docking revealed that B3 binds strongly to calf thymus DNA via hydrophobic interactions and groove binding, and exhibits selective binding to bovine serum albumin (site II, subdomain IIIA). These results highlight the potential of cobalt(II) complexes as multifunctional agents with significant antimicrobial and antitumor activities and provide detailed insight into their molecular interactions with DNA and serum proteins.

1. Introduction

A variety of analytical and spectroscopic methods have been applied to investigate the interactions of transition metal complexes with biological macromolecules [1]. A combination of analytical and spectroscopic techniques, including UV–Vis absorption and fluorescence quenching studies, provides valuable insight into electronic transitions, complex formation, and the binding mechanisms of metal complexes with biomacromolecules such as DNA and proteins [2]. Viscosity and thermal denaturation studies clarify DNA binding modes, differentiating intercalative from groove interactions, while molecular docking complements these experiments by visualizing preferred binding sites and estimating interaction energies at the atomic level [3].

The continuous search for improved therapeutic agents has expanded toward metal-based compounds, which possess unique physicochemical and coordination properties that can be exploited for biological applications [4,5,6]. While platinum-based drugs have dominated metal-based chemotherapy, their use is restricted by severe nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, and resistance development [7,8,9,10]. Consequently, increasing attention has been directed toward transition-metal complexes containing biocompatible or endogenous elements as potentially safer and more versatile alternatives [11].

Among them, cobalt(II) complexes have attracted particular interest due to their wide range of oxidation states, variable coordination geometries, and the ability to participate in redox and catalytic processes relevant to biological systems [12,13]. These properties contribute to their demonstrated antitumor and antimicrobial activities, as well as their capability to interact with essential biomolecules, such as DNA and proteins [14,15]. Understanding these interactions is crucial, as the biological efficacy of metal complexes is closely linked to their binding affinity, mode of interaction, and induced structural changes in biomolecular targets.

The toxicity of cobalt-based compounds is often associated with the release of free Co(II) ions, which can induce oxidative stress, disrupt cellular redox balance, and interact nonspecifically with biomolecules. The biological activity of cobalt complexes is strongly influenced by their ligand environment and geometry, which can be tuned to direct reactivity toward specific biological targets. Moreover, insufficient stability or rapid ligand exchange under physiological conditions may exacerbate undesired cytotoxic effects [16].

β-Diketo esters are versatile chelating ligands that stabilize metal ions through the keto–enol tautomeric system, forming coordination frameworks with high stability and potential biological relevance [17]. Their derivatives have produced bioactive complexes with several metal ions, including magnesium (antiviral activity) [18], copper (antibacterial) [19], and palladium (antitumor) [20]. The incorporation of β-diketo ester ligands into cobalt(II) complexes is expected to enhance both stability and biomolecular affinity, potentially leading to improved therapeutic profiles.

In this study, we report the synthesis and characterization of novel cobalt(II) β-diketo ester complexes. Their interactions with calf thymus DNA (CT-DNA) and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were systematically investigated using spectroscopic techniques and molecular docking. The aim is to elucidate the physicochemical basis of their binding mechanisms and to correlate these findings with their observed biological activities. This integrative analytical approach provides new insights into the molecular behavior of cobalt(II) complexes and supports their potential as multifunctional bioactive agents.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General

Ligands A1–4 were synthesized according to the procedure described in our previous publications [19,20,21]. All reagents, substrates, and solvents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and used without further purification. CT-DNA, ethidium bromide (EB), 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5-[5-(4-methylpiperazine-1-yl)-benzimidazo-2-yl]-benzimidazole (HOE), BSA, eosin Y, and ibuprofen were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA) and used as received. The stock solution of CT-DNA was prepared in physiological phosphate buffer (PBS). The purity of the CT-DNA solution was assessed by measuring absorbance at 260 nm and 280 nm, and the A260/A280 ratio was calculated. A ratio of approximately 1.8–1.9 indicated that the DNA sample was sufficiently free of protein impurities. The DNA concentration was determined using a molar extinction coefficient of 6600 M−1 cm−1 at 260 nm [22]. Stock solutions of EB/HOE, BSA, and eosin Y/ibuprofen were prepared in PBS to final concentrations of 1000 µM, 20 µM, and 500 µM, respectively. All stock solutions were stored at 4 °C and used within five days. UV–Vis absorption spectra were recorded on a PerkinElmer Lambda 35 double-beam spectrophotometer using 3 mL quartz cuvettes with a 1.0 cm path length. Fluorescence spectra were obtained on a Shimadzu RF-1501 PC spectrofluorometer equipped with 10 nm excitation and emission bandwidths. Infrared (IR) spectra were recorded on a PerkinElmer Spectrum One FT-IR spectrometer using KBr pellets. Data acquisition and analysis were carried out using Origin 2018 (64-bit) and Microsoft Excel 2017 software.

2.2. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Cobalt(II) Complexes B1–4

All cobalt(II) complexes were synthesized following the procedure previously reported by our group [15]. The ligand (2 mmol) was dissolved in 5 mL of ethanol at room temperature. A solution of CoSO4 (1 mmol) in 5 mL of water was then added dropwise to the ligand solution. A precipitate formed almost immediately upon mixing. After allowing the reaction to proceed for 5 h, the precipitate was filtered, washed with methanol, and left to dry at room temperature. The dried precipitate was subsequently recrystallized in a 3 mL mixture of DMSO and methanol (1:2 v/v). Crystals were allowed to form over 24 h, after which they were filtered, dried under vacuum, and subjected to elemental analysis. The progress of the reaction was monitored by thin-layer chromatography, using a mobile phase of CH2Cl2: EtOH (9:1). All Co(II) complexes were characterized via UV-Vis (Figure S1), IR (Figure S2), and MS spectroscopy, and elemental analysis.

[Co(A1)2DMSO2] (B1): Red powder; yield: 80%; mp = 120 °C; UV-Vis (λmax/nm, (log(ε/M−1 cm−1)): 344(3.54). IR (KBr): ν 3411, 2955, 1732, 1571, 1520, 1457, 1422, 1271 cm−1. ESI-MS (m/z) = 654.4 [M + H]+. Calcd for C28H34O10S2Co (%): C 43.30, H 4.54; found: C 43.34, H 4.55.

[Co(A2)2DMSO2] (B2): Red powder; yield: 79%; mp = 101 °C; UV-Vis (λmax/nm, (log(ε/M−1 cm−1)): 350(3.62). IR (KBr): ν 3399, 2070, 1728, 1582, 1514, 1490, 1446, 1277, 1213, 1039, 1024 cm−1. ESI-MS (m/z) = 714.5 [M + H]+. Calcd for C30H38O12S2Co (%): C 50.49, H 5.37; found: C 50.53, H 5.35.

[Co(A3)2DMSO2] (B3): Red powder; yield: 83%; mp = 136 °C; UV-Vis (λmax/nm, (log(ε/M−1 cm−1)): 369(3.85). IR (KBr): ν 3400, 2975, 1729, 1569, 1507, 1443, 1432, 1257, 1157, 1017, 968 cm−1. ESI-MS (m/z) = 706.5 [M + H]+. Calcd for C32H38O10S2Co (%): C 54.46, H 5.43; found: C 54.49, H 5.41.

[Co(A4)2DMSO2] (B4): Red crystals; yield: 86%; mp = 129 °C; UV-Vis (λmax/nm, (log(ε/M−1 cm−1)): 358(3.76), 276(3.38). IR (KBr): ν 3398, 1726, 1524, 1497, 1443, 1411, 1285, 1249, 1015 cm−1. ESI-MS (m/z) = 666.4 [M + H]+. Calcd for C24H3O10S4Co (%): C 43.30, H 4.54; found: C 43.35, H 4.53.

2.3. Antimicrobial Activity

The in vitro antimicrobial activity of the synthesized complexes B1–4 was evaluated against a panel of bacterial and fungal strains obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The bacterial species included Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633), Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923), Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), Proteus mirabilis (ATCC 29906), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC 70063). The fungal panel comprised Aspergillus fumigatus (ATCC 1022), Mucor mucedo (ATCC 20094), Candida albicans (ATCC 10259), Microsporum canis (ATCC 36299), and Trichophyton rubrum (ATCC 28188).

Bacterial strains were maintained on Mueller–Hinton (MH) agar, whereas fungal strains were cultivated on Sabouraud dextrose (SD) agar. All cultures were stored at 4 °C until use. Bacterial inocula were prepared from 24-h-old cultures and suspended in sterile distilled water to achieve a turbidity corresponding to approximately 108 CFU/mL. Fungal suspensions were prepared from 3–7-day-old cultures in sterile distilled water, adjusted to contain approximately 106 CFU/mL [23].

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of complexes B1–4 was determined using a 96-well microdilution assay [24]. Resazurin was employed as a colorimetric indicator of bacterial cell viability, while fungal growth was assessed visually. Streptomycin and ketoconazole were used as standard reference drugs for bacteria and fungi, respectively, whereas DMSO served as the negative control.

All data is presented as mean ± standard deviation of the results of three parallel measurements. Statistical evaluations were carried out using Microsoft Office Excel (Microsoft Excel for Microsoft 365 MSO) and SPSS software (version 26, IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA). t-tests were used in determining the statistical significance of the difference between the controls and the samples, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.4. Cytotoxic Activity

2.4.1. Cell Culture

The SW480 human colorectal carcinoma and HaCaT normal human keratinocyte cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and CLS Cell Lines Service (Eppelheim, Germany), respectively. Both cell lines were maintained according to standard cell culture protocols, as previously described in detail [25].

2.4.2. Evaluation of Cytotoxicity Using the MTT Assay

The cytotoxic potential of the synthesized cobalt(II) complexes B1–4 toward colon cancer (SW480) and normal (HaCaT) cell lines was assessed using the MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] assay [26]. This colorimetric method is based on the ability of viable cells to metabolize the tetrazolium salt into insoluble purple-blue formazan crystals, which can be quantified spectrophotometrically.

For the assay, 1 × 104 cells per well were seeded in 96-well plates and allowed to adhere for 24 h. The cells were then treated with varying concentrations of each compound (ranging from 1 to 200 µM) prepared in 100 µL of culture medium. Untreated cells incubated with culture medium alone served as the control group. Cell viability was assessed after 24 h and 72 h of incubation. Following the exposure period, the formed formazan crystals were dissolved in 150 µL of DMSO, and the absorbance was measured. The absorbance values were directly proportional to the number of metabolically active (viable) cells, providing an indirect measure of cytotoxicity.

The IC50 values (concentration required to inhibit 50% of cell viability) were calculated using CalcuSyn 2.0 software. The selectivity index (SI) was determined as the ratio of IC50 values in normal (HaCaT) vs. cancer (SW480) cells, providing a measure of compound selectivity toward malignant cells.

For determining the cytotoxicity, all measurements were performed in triplicate and IC50 values were expressed as mean values ± standard deviation. The obtained data were processed using SPSS statistical software package (IBM SPSS Statistics Version 23, 2015).

2.4.3. Cell Morphology Analysis

To investigate morphological alterations associated with cell death, SW480 and HaCaT cells (1 × 104 cells per well) were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h to allow attachment. Cells were then treated with the B3 complex (the compound exhibiting the highest cytotoxic activity) at its IC50 concentration, in a total volume of 100 µL of culture medium, and further incubated for 24 h.

Following incubation, cells were stained with a 1:1 mixture of acridine orange (AO) and ethidium bromide (EB) by adding 10 µL of each dye solution (100 µg/mL). The stained cells were examined under a Nikon Ti-Eclipse fluorescence microscope at 400× magnification. Changes in cell and nuclear morphology were analyzed to distinguish between viable, apoptotic, and necrotic cells, as this method allows clear differentiation of cell death modes based on fluorescence patterns.

2.5. DNA-Binding Studies

2.5.1. Absorption Spectroscopic Studies

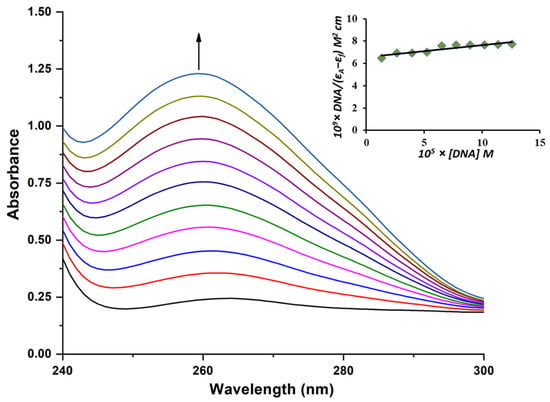

To determine the binding constant (Kb), thermodynamic parameters, and the mode of interaction between the cobalt(II) complex B3 and CT-DNA, UV–Vis absorption spectra were recorded at three different temperatures. The titration experiments were performed using a fixed concentration of B3 and increasing concentrations of CT-DNA. Spectra were recorded immediately after each addition of CT-DNA solution to ensure equilibrium conditions.

The concentration of B3 was maintained at 13.5 µM, while the CT-DNA concentration ranged from 13.4 µM to 126 µM (corresponding to a [DNA]/[B3] ratio up to 10), with appropriate dilution corrections applied. The equations used are given in Equations (S1)–(S3) [27,28].

2.5.2. Ethidium Bromide (EB) and HOE Displacement Studies

Fluorescence emission spectroscopy was employed to examine the ability of the synthesized cobalt(II) complex B3 to competitively displace ethidium bromide (EB) or 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5-[5-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-benzimidazo-2-yl]-benzimidazole (HOE) from their respective DNA adducts.

For these competitive binding experiments, a series of solutions containing complex–EB–CT-DNA or complex–HOE–CT-DNA were prepared. Each solution contained a constant concentration of CT-DNA (5 µM) and EB or HOE (5 µM), while the concentration of B3 was varied between 5 µM and 50 µM. The fluorescence measurements were carried out using excitation wavelengths of 527 nm for EB and 346 nm for HOE, with corresponding emission ranges of 550–750 nm and 360–600 nm, respectively.

The Stern–Volmer quenching constants (Ksv) were calculated for both systems using Equation (S4) [29], to evaluate the efficiency of fluorescence quenching and the strength of the competitive interactions between B3 and the DNA-bound fluorophores.

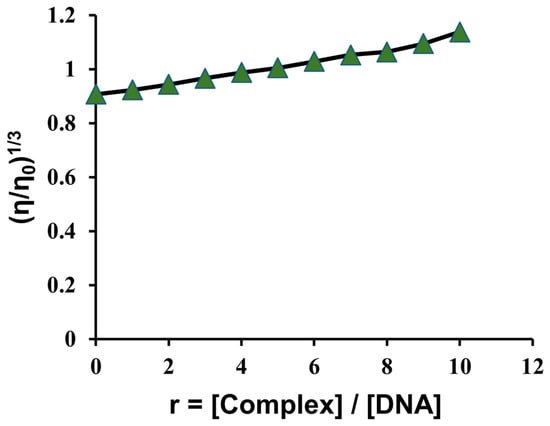

2.5.3. Viscosity Measurements

The viscosity measurements were performed using an Anton Paar Lovis 2000 M/ME rolling-ball viscosimeter (Anton Paar GmbH, Graz, Austria). To evaluate the effect of B3 on DNA viscosity, solutions were prepared with varying concentrations of B3 (10.95–109.5 µM) and a constant concentration of CT-DNA (10.95 µM), yielding [B3]/[DNA] ratios from 1 to 10.

The viscosity of the free CT-DNA solution was denoted as η0, while η represented the viscosity of DNA in the presence of B3. Measurements were conducted at 298 K. The relative viscosity changes were analyzed by plotting (η/η0)1/3 as a function of the [B3]/[DNA] ratio to assess the mode of DNA interaction (intercalative or non-intercalative).

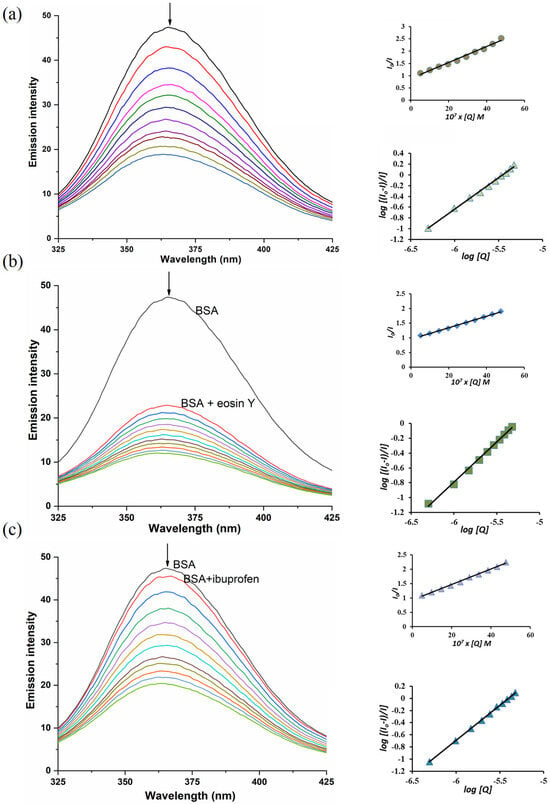

2.6. Albumin-Binding Studies

The interaction mechanism between the cobalt(II) complex B3 and BSA, both in the absence and presence of site-specific markers (eosin Y and ibuprofen), was investigated using fluorescence emission spectroscopy. The fluorescence spectra were recorded at an excitation wavelength of 295 nm, with emission collected in the 300–500 nm range.

To determine the binding constants and interaction characteristics, titration experiments were performed by maintaining constant concentrations of BSA, eosin Y, and ibuprofen (2 µM each), while gradually increasing the concentration of B3 from 4.98 µM to 47.6 µM (corresponding to molar ratios up to 2.5, with dilution corrections applied). The calculations of the binding constants and related parameters were carried out using Equations (S5)–(S7) [29,30].

Control measurements confirmed that B3 alone exhibited no detectable fluorescence under identical experimental conditions, indicating that observed emission changes were solely due to its interaction with BSA.

2.7. Molecular Docking Studies

Molecular docking simulations were carried out using Molegro Virtual Docker (MVD) [31], which provides built-in parameterization suitable for heavy transition metals [32,33]. The three-dimensional structures of target biomolecules were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (rcsb.org) [34]. The following crystal structures were employed: 1BNA (DNA duplex for groove-binding analysis) [35], 1Z3F (DNA structure used to evaluate intercalation) [36], and 4JK4 (bovine serum albumin, BSA, for protein-binding site assessment) [37].

The ligand structure of the investigated cobalt(II) complex was initially modeled and pre-optimized using MOPAC2016 with the PM6 semi-empirical method [38]. Further optimization was performed with Gaussian 09, employing the B3LYP/LANL2DZ level of theory [39,40,41]. The protein and DNA structures were prepared by removing co-crystallized ligands and water molecules, where applicable. DNA molecules were additionally modified for docking according to previously established protocols [33]. All processed structures were subsequently imported into MVD for docking analysis.

For BSA, docking search spaces with 15 Å radii were centered around the original ligand-binding sites. The DNA intercalation site was defined by a 15 Å radius around the intercalation cavity, whereas for groove-binding simulations, a 25 Å search sphere was set to encompass the entire DNA structure. Exact coordinates of binding sites are in Table S1. The docking algorithm used was MolDock SE, with scoring based on the MolDock Score function [42]. In accordance with recent studies [15,43], default parameters were generally retained, except that ligand evaluations included internal electrostatic interactions, internal hydrogen bonding, and sp2–sp2 torsional terms. The number of algorithm runs was increased to 20 to ensure adequate sampling of conformational space.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis of Novel Cobalt(II) Complexes B1–4

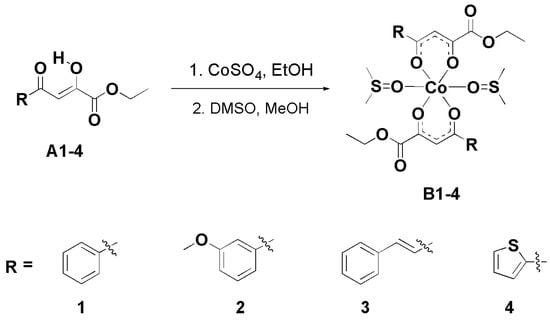

All β-diketonate ligands A1–4 were previously synthesized via the Claisen condensation of diethyl oxalate with the corresponding methyl ketone under basic conditions [19,20,21]. Building upon these biologically relevant ligands, four novel cobalt(II) complexes were prepared. In the first step, the ligands were coordinated to the Co(II) center using CoSO4. Subsequently, two molecules of DMSO were coordinated to the Co(II) ion to afford the final complexes B1–4, which adopt an octahedral geometry (Scheme 1). The octahedral coordination of the cobalt(II) complexes bearing ligands of the same type has been confirmed by X-ray crystallography, as reported in our previous study [15]. The reactions proceeded with high yields, reaching up to 86%. The newly synthesized cobalt(II) complexes were characterized using UV–Vis and FTIR spectroscopy, mass spectrometry (MS), and elemental analysis.

Scheme 1.

Reaction procedure for synthesis of novel cobalt(II) complexes B1–4.

The IR spectra of the free ligands (A1–4) and their corresponding cobalt(II) complexes (B1–4) provide important insights into the coordination behavior of the β-diketo enol system. In the spectra of the ligands, strong bands are observed in the ~1600 cm−1 region. These are attributed to conjugated ν(C=O)/ν(C=C) stretching vibrations, arising from delocalization of π-electrons across the β-diketo enol moiety. This intramolecular conjugation results in mixed vibrational modes that are lower in frequency than the typical unconjugated C=O stretch (~1700 cm−1). Upon coordination with cobalt(II), these bands shift to lower wavenumbers (~1580 cm−1), indicating a reduction in carbonyl bond order due to electron donation to the metal center. This shift confirms the involvement of the carbonyl oxygen in the coordination process. Additionally, the ν(C–O) (enolic) bands, observed between ~1230 cm−1 in the free ligands, shift to higher values (~1250 cm−1) in the complexes. This change supports coordination via the enolic oxygen, likely following deprotonation. Together, these spectral changes confirm that cobalt(II) coordinates through the enolic oxygen and carbonyl oxygen, forming stable six-membered chelate rings [44,45,46]. These findings are consistent with the expected structure and are supported by elemental analysis data, confirming the proposed stoichiometry.

3.2. Biological Evaluation

3.2.1. Antimicrobial Activity of Cobalt(II) Complexes B1–4

The antimicrobial activity of the synthesized cobalt(II) complexes B1–4 was assessed by determining their minimum inhibitory concentrations against a range of microorganisms, including pathogens associated with human, animal, and plant diseases, mycotoxin producers, and food spoilage organisms. As shown in Table 1 and Table 2, all complexes effectively inhibited microbial growth, with MIC values ranging from 0.01 to 7.5 mg/mL. Among them, B1 exhibited the strongest antimicrobial activity, showing the best antibacterial effect against Staphylococcus aureus and Proteus mirabilis (MIC = 0.23 mg/mL). For the tested fungi, B1 displayed MIC values between 0.01 and 0.46 mg/mL. Complex B2 also demonstrated potent antifungal activity at low concentrations, closely following B1, while B3 exhibited the weakest overall antimicrobial effect.

Table 1.

Antibacterial activity of tested cobalt(II) complexes B1–4.

Table 2.

Antifungal activity of tested cobalt(II) complexes B1–4.

Among the bacterial species tested, S. aureus and P. mirabilis were the most sensitive to all cobalt(II) complexes. Regarding the fungi, Microsporum canis and Trichophyton rubrum, which are pathogenic dermatophytes, showed the highest susceptibility.

The antimicrobial performance of the cobalt(II) complexes was compared with standard antibiotics, namely, streptomycin for bacteria and ketoconazole for fungi. The results indicated that the standard drugs exhibited similar or higher activity than the tested complexes. DMSO, used as a negative control, showed no inhibitory effect on any of the tested microorganisms.

In this study, the synthesized cobalt(II) complexes exhibited greater antifungal activity than antibacterial effects. The enhanced activity against fungi may be linked to their ability to reduce ergosterol content, a key component of fungal cell membranes that is critical for maintaining membrane integrity and proper cellular function. Additionally, these complexes can interfere with essential cellular processes, including cell volume regulation, intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, and mitochondrial function, ultimately compromising fungal viability. The tested complexes were also capable of inhibiting conidial germination and mycelial growth, further contributing to their antifungal effects.

Overall, complexes B1 and B2 demonstrated the most pronounced antimicrobial activity, suggesting that they hold promise as novel candidates for the development of effective antimicrobial agents.

3.2.2. Cytotoxic Activity of Cobalt(II) Complexes B1–4

Research on metal-based chemotherapeutics has intensified since the discovery of cisplatin and related complexes as potent anticancer agents. However, the clinical applications of such metal-based drugs are often limited by toxicity toward non-transformed human cells and the development of drug resistance. Consequently, there is a growing demand for novel metal-based complexes with improved efficacy, safety profiles, and rational design strategies. Among these, cobalt complexes have been extensively investigated and are considered promising candidates [47]. Previous studies have reported the cytotoxicity of cobalt(III) complexes against MCF-7 breast cancer cells [48] and multiple other cancer cell lines [12].

In the present study, the MTT assay was used to evaluate cell viability following treatment with cobalt(II) complexes B1–4. The IC50 values, which serve as indicators of cytotoxic potential in preclinical anticancer evaluation, were determined and are presented in Table 3. The cytotoxic effects of the cobalt(II) complexes were dose-dependent on normal cells, whereas cancer cells exhibited partial recovery after extended exposure to B1 and B4. One possible explanation is that tumor cells may recover over time and adapt to the treatment. They can also activate various resistance mechanisms that allow survival and evasion, such as enhanced DNA-repair pathways, increased drug efflux, altered drug targets, and metabolic reprogramming [49]. The possibility of compound instability can be excluded, as the compound produces a more pronounced effect in healthy cells. Among all tested complexes, B3 displayed the most pronounced cytotoxicity at both 24 h and 72 h, while B2 exhibited significant cytotoxic effects after 72 h. The remaining complexes showed moderate to good activity, as reflected in their IC50 values.

Table 3.

IC50 values (µM) of cobalt(II) complexes B1–4 on SW480 and HaCaT cell lines. The results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

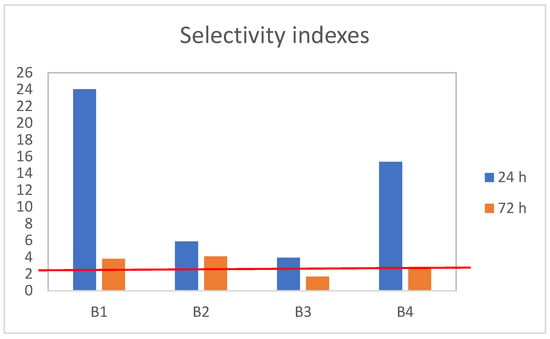

The selectivity index (SI) was calculated to predict the therapeutic potential and toxicity of the cobalt(II) complexes against normal cells. The SI was calculated for each compound using the formula: SI = IC50 for the normal cell line, HaCaT/IC50 for the respective cancerous cell line, SW480. An SI value greater than 3.0 is generally considered desirable for anticancer agents, indicating preferential toxicity toward tumor cells over normal cells [50]. As shown in Figure 1, all tested complexes demonstrated selectivity after 24 h, whereas B3 and B4 showed reduced selectivity after 72 h. Overall, the treatments resulted in higher cytotoxicity toward cancer cells compared with normal cells, highlighting the potential of these cobalt(II) complexes as anticancer candidates.

Figure 1.

The SI values as an indicator of the selectivity of cobalt(II) complexes B1–4 toward cancer cells. Red line is relative value of control sample.

3.2.3. Cell Morphological Analysis

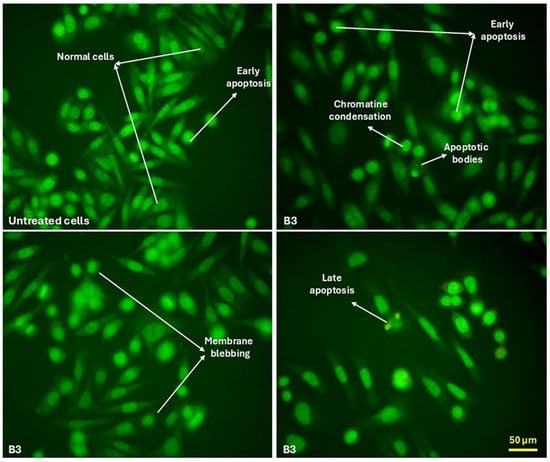

The MTT assay is one of the most commonly employed methods for assessing cell proliferation and viability; however, it does not provide information on the mode of cell death induced by a treatment. To address this limitation, we further examined the morphology of SW480 cells to identify structural alterations following exposure to the compounds. Morphological evaluation using fluorescence microscopy was conducted after treatment with B3, the compound exhibiting the most pronounced cytotoxicity.

The analysis revealed a reduction in cell confluence accompanied by multiple morphological changes characteristic of apoptosis. Observed alterations included loss of adhesion, disruption of cell–cell contacts, nuclear condensation with enhanced fluorescent signal, membrane shrinkage, and formation of apoptotic bodies (Figure 2). These features are consistent with apoptotic cell death, which appears to be the predominant mechanism induced by B3, whereas necrotic changes were minimal.

Figure 2.

Morphological changes in SW480 cells indicative of apoptosis following treatment with B3.

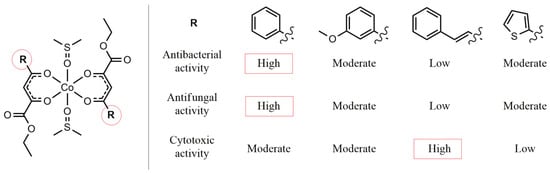

3.2.4. Structure–Activity Relationship (SAR) Analysis of Cobalt(II) Complexes B1–4

The biological activity of cobalt(II) complexes B1–4 is strongly influenced by the nature of the aryl substituent (R) on the ligand (Figure 3). Complex B1, containing a phenyl group, showed the highest antibacterial and antifungal activities, while B3, with a styryl group, was the least active, likely due to steric hindrance and reduced solubility. Complexes B2 (m-methoxyphenyl) and B4 (thiophenyl) displayed intermediate activity, suggesting that electronic effects and heteroaryl interactions can modulate potency. Overall, the results indicate that planar aromatic groups enhance bioactivity, whereas bulky or electron-rich substituents tend to decrease antimicrobial efficacy.

Figure 3.

Structure–activity relationship analysis of cobalt(II) complexes B1–4.

The cytotoxic activity of cobalt(II) complexes B1–4 against SW480 and HaCaT cell lines is clearly influenced by the nature of the aryl substituent (R) on the ligand. Complex B3, containing a styryl group, exhibited the highest antitumor activity, with the lowest IC50 values, particularly after 72 h exposure, suggesting that the extended conjugated system may enhance interaction with cellular targets. Complex B1 (phenyl) showed moderate activity on SW480 cells but relatively low toxicity toward HaCaT cells, indicating some selectivity. B2 (m-methoxyphenyl) displayed moderate cytotoxicity on both cell lines, while B4 (thiophenyl) showed the least activity overall. These results suggest that extended conjugation in the aryl substituent can enhance antitumor potency, whereas simple or bulky heteroaryl groups may reduce efficacy.

3.3. Investigation of Binding Properties of Cobalt Complex with CT-DNA

For many transition metal complexes, DNA has been identified as a primary biological target, with two main modes of interaction: covalent and non-covalent binding. In the covalent binding mode, the complex forms a direct bond with DNA, typically at the N7 position of the guanine base. The non-covalent interactions, on the other hand, include intercalative, electrostatic, and groove (surface) binding modes [51].

Among the various analytical methods, fluorescence and UV-Vis spectroscopy are most commonly employed to elucidate the potential binding mechanisms of metal complexes with DNA. The present study aimed to investigate the interaction between the cobalt(II) complex B3 and CT-DNA using UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy, fluorescence quenching, and viscosity measurements.

The absorption titration of B3 was performed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), maintaining a constant complex concentration of 13.5 µM, while gradually increasing the CT-DNA concentration from 13.4 µM to 136 µM (molar ratio up to 10). The absorption spectra were recorded at three temperatures: 288, 298, and 310 K. Upon successive additions of CT-DNA, a hyperchromic effect was observed at 260 nm, indicating an increase in absorbance (Figure 4 and Figure S3). This hyperchromism suggests the involvement of non-covalent interactions, such as electrostatic attraction, hydrogen bonding, and groove binding, which likely contribute to the stabilization of the B3–DNA complex [27]. Moreover, a blue shift from 264 nm to 260 nm was detected, further supporting the presence of these interactions.

Figure 4.

Absorption spectra of B3 at 310 K in PBS buffer upon addition of CT-DNA. [B3] = 13.5 µM; [DNA] = 13.4–136 µM. The arrow presents the addition of an increasing concentration of DNA. Insert: plot of [DNA]/(εa-εf) vs. [DNA].

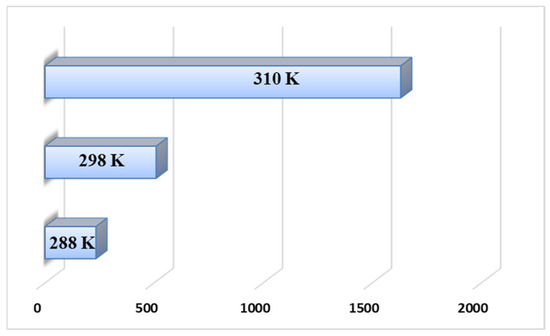

The intrinsic binding constant (Kb) was calculated using Equation (S1), whereas the thermodynamic parameters were derived from Equations (S2) and (S3). All corresponding values are summarized in Table 4. A comparison of the intrinsic binding constants obtained at different temperatures revealed that the Kb value at 310 K was significantly higher than those at lower temperatures (Figure 5), suggesting a stronger affinity of B3 toward CT-DNA under physiological conditions, namely, the optimal temperature of the human body.

Table 4.

DNA-binding constant (Kb) and thermodynamic parameters for the CT-DNA/B3 system.

Figure 5.

Comparison of binding constants at different temperatures.

The activation parameters (ΔH0 and ΔS0) provide valuable insight into the nature of the binding interaction. Previous studies have established that when both parameters are positive, hydrophobic interactions are predominant; when the enthalpy change is close to zero and the entropy change is positive, electrostatic forces are the main contributors; and when both parameters are negative, hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces are the dominant interactions [52]. As presented in Table 4, both activation parameters for the B3–CT-DNA system are positive, indicating that hydrophobic forces play a major role in the complex formation. In addition, the negative Gibbs free energy (ΔG0) confirms the spontaneous nature of the binding process.

The Van’t Hoff plot of ln Kb vs. 1/T (Figure S4) shows a high degree of linearity (R2 = 0.993), indicating that the system obeys the classical Van’t Hoff model within the tested temperature range. The slope of the line corresponds to ΔH0 = +65.97 kJmol−1, while the intercept yields ΔS0 = +273.95 JKmol−1.

The displacement of DMSO from the complex surface is both enthalpically unfavorable (breaking strong DMSO-ligand interactions, positive ΔH0) and entropically favorable (release of structured DMSO molecules into bulk solvent; large positive ΔS0). Such DMSO-driven desolvation processes are well known to generate unusually large thermodynamic parameters compared to the displacement of water alone. Therefore, the observed values of ΔH0 and ΔS0 are consistent with a binding mechanism in which DMSO-containing solvation layers are disrupted during formation of the DNA/BSA-complex adduct.

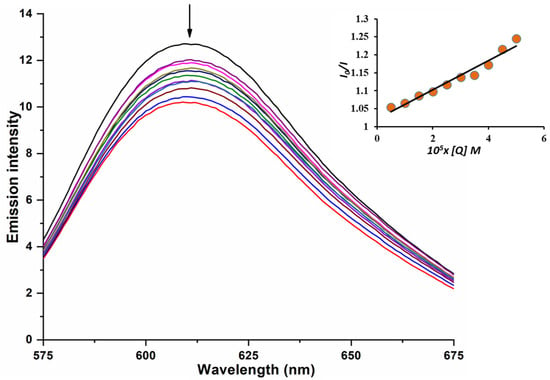

To gain further insight into the binding mechanism of B3 with CT-DNA, competitive fluorescence experiments were performed using 3,8-diamino-5-ethyl-6-phenylphenanthridinium bromide (ethidium bromide, EB) and a synthetic N-methylpiperazine derivative (HOE) as reference probes.

Ethidium bromide is a planar, positively charged dye widely used as a fluorescent marker for nucleic acids. In its unbound form, EB exhibits weak fluorescence; however, upon intercalation between DNA base pairs, it becomes highly fluorescent due to restricted rotational freedom and strong interaction with the DNA double helix [53]. It has been reported that the enhanced fluorescence of the CT-DNA–EB complex can be quenched when a competing molecule interacts with the DNA [54].

Upon gradual addition of B3, a marked decrease in fluorescence intensity at 610 nm was observed, indicating that B3 competes with EB for DNA binding sites (Figure 6). The observed fluorescence quenching of the CT-DNA–EB system suggests that B3 displaces EB from its intercalation sites, confirming that B3 directly interacts with CT-DNA.

Figure 6.

EB-CT-DNA emission spectra with B3. [B3] = (5–50 µM); [EB] = [CT-DNA] = 5 µM. Following the addition of B3, the arrow illustrates the change in emission intensity. Insert graph: Plot of I0/I vs. Q.

The Stern–Volmer plot illustrates the relationship between the fluorescence intensity ratio (I0/I) and the concentration of the tested complex B3 (Q) (Figure 6, inset). The observed linear correlation indicates a single quenching mechanism, enabling the determination of the Stern–Volmer quenching constant (Ksv) using Equation (S4). The calculated values are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Stern-Volmer constant (Ksv) obtained for competitive fluorescence measurements.

The cobalt(II) complex B3 exhibits a very limited capacity to displace ethidium bromide (EB) and intercalate into CT-DNA, as evidenced by the low value of the Stern–Volmer constant. The binding constant for EB, which intercalates between DNA base pairs, is 1.4 × 106 M−1, further confirming the weak binding affinity of complex B3 [55].

The synthetic N-methylpiperazine derivative HOE interacts with DNA primarily through minor groove binding. With increasing DNA concentration, the fluorescence intensity of HOE typically rises due to its high planarity. Conversely, when certain transition-metal complexes bind to DNA, they can displace HOE, leading to a decrease in the fluorescence intensity of the HOE–DNA system [51].

In this experiment, the concentration of B3 was gradually increased while maintaining a constant concentration of the HOE/CT-DNA complex. The characteristic emission spectra of HOE bound to CT-DNA, in the presence and absence of the cobalt complex, are presented in Figure S5. Upon the addition of B3 to the HOE–CT-DNA system, the fluorescence intensity at 476 nm markedly decreased, indicating that the investigated complex binds to DNA, replacing HOE. Although the binding constants of HOE and EB are comparable, as shown by their respective Stern–Volmer constants (Table 5), the slight difference between them is insufficient to definitively clarify the DNA-binding mechanism of B3.

To further elucidate the mode of DNA binding, the interaction of B3 with CT-DNA was examined using viscosity measurements. Hydrodynamic techniques such as viscosity and sedimentation assays are highly sensitive to changes in DNA length, and thus provide one of the most reliable indicators of binding mode in solution when crystallographic data are unavailable. Classical intercalation typically results in DNA helix elongation and a corresponding increase in viscosity, as the base pairs are separated to accommodate the intercalating ligand [56]. In the present study, a slight increase in DNA viscosity was observed with increasing concentrations of B3 (Figure 7), suggesting that the complex binds primarily through a groove-binding mode rather than full intercalation [57].

Figure 7.

CT-DNA (10.95 µM) relative viscosity (η/ηo)1/3 in PBS buffer with increasing concentration of B3 (10.95–109.5 µM).

These findings are consistent with the previously determined Stern–Volmer constants for EB and HOE, supporting the experimental observations. However, the small differences observed in the Stern–Volmer constant values (Table 5) are insufficient to conclusively determine the exact binding mode. Therefore, to gain deeper insight into the interaction mechanism, a molecular docking analysis was performed within the scope of this study.

3.4. Albumin Binding Studies

Understanding the interactions between metal complexes and proteins is increasingly important for elucidating their pharmacokinetic and pharmacological properties. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) possesses three intrinsic fluorophores—tryptophan (Trp), tyrosine (Tyr), and phenylalanine (Phe). Among these, Trp, which contains an indole moiety, is the principal contributor to BSA intrinsic fluorescence [58]. The fluorescence contributions of Tyr and Phe are typically negligible: Tyr fluorescence is largely quenched when ionized or positioned near amino or Trp residues, while Phe exhibits a very low quantum yield. Consequently, the binding affinity of a metal complex can be evaluated through variations in the Trp emission intensity (upon excitation at 295 nm) [59].

Upon the addition of B3 to the BSA solution, a marked decrease in fluorescence intensity was observed (Figure 8), indicating that the microenvironment of the Trp residue was altered due to complex formation between B3 and BSA. Furthermore, a blue shift in the BSA emission maximum from 366 nm to 363 nm provides additional evidence for significant interactions between B3 and the Trp residue of the protein.

Figure 8.

(a) Adding B3 to BSA; (b) Adding B3 to BSA-eosin Y; (c) Adding B3 to BSA-ibuprofen. Left–emission spectra; Right–plots of I0/I vs. [Q] (up) and log[(I0 − I)/I] vs. log[Q] (down). Concentrations [BSA] = [eosin Y] = [ibuprofen] = 2 µM, [B3] = 4.98–47.6 µM. The arrows show the change in emission intensity after the addition of complex B3.

The binding parameters, calculated using the Stern–Volmer and Hill equations (Equations (S5)–(S7)), are summarized in Table 6. The obtained binding constant (K) value indicates that the cobalt(II) complex B3 exhibits a strong affinity toward BSA, with approximately one primary binding site involved in the interaction.

Table 6.

Binding parameters for cobalt complex B3 with BSA (without and with site markers).

The binding site of the cobalt(II) complex B3 on BSA was further elucidated through competitive binding experiments using established site-specific markers. Ibuprofen was employed as the marker for site II (subdomain IIIA), while eosin Y served as the marker for site I (subdomain IIA) [52]. As shown in Figure 8, a gradual decrease in fluorescence intensity was observed during titration, confirming the successful binding of each marker to BSA (as evident from the difference in fluorescence between BSA with and without the marker). Upon addition of the B3 complex, a competitive displacement between B3 and the corresponding site marker occurred.

The higher Stern–Volmer constant (Ksv) value obtained for the BSA–ibuprofen system, as presented in Table 6, indicates a stronger interaction in this system compared to BSA–eosin Y. This finding suggests that B3 preferentially binds at site II (subdomain IIIA) on the BSA molecule.

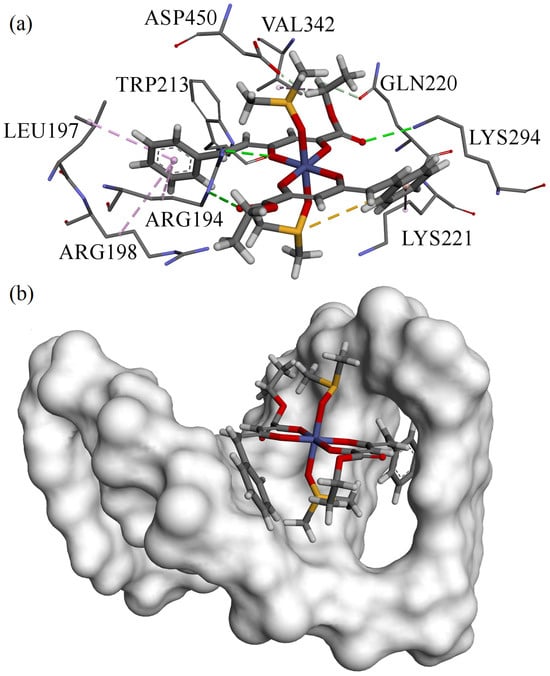

3.5. Molecular Docking Studies

Molecular docking is a computational approach used to predict the preferred orientation of a molecule when bound to a specific macromolecular target. It allows the efficient exploration of possible binding conformations, while scoring functions provide a means to evaluate the quality of generated poses and estimate the relative binding affinity toward various biological targets.

In this study, the binding affinity of compound B3 was investigated with multiple BSA domains and two distinct DNA binding modes. Docking simulations were carried out using the MolDock SE algorithm in combination with the MolDock Score as the scoring function.

For each binding site, the MolDock SE algorithm was executed 20 independent runs, and the five best docking poses were selected based on the MolDock Score. These poses were subsequently rescored to determine the most favorable docking conformation (Table 7). Docking to BSA was performed on all domains that contained a co-crystallized ligand in the target structure, excluding domain IB. Additionally, domain IIIB was omitted from the final results because no valid docking pose could be generated by the algorithm.

Table 7.

Lowest energy poses based on the reranked score, derived from docking simulations. Magnitudes are dimensionless because the calculation of scores is loosely based on interaction energy, but it is not comparable [27].

The obtained results revealed that B3 exhibits the highest binding affinity for domain IIIA, which corresponds to binding site II of BSA. A weaker affinity was observed for the binding site within domain IIA, whereas domain IA displayed moderate binding strength. These findings confirm that B3 is capable of binding to BSA, with a slight preference for domain IIIA. The lowest-energy docking pose and its surrounding amino acid residues are illustrated in Figure 9a.

Figure 9.

Best poses of structure B3 obtained from docking towards (a) BSA; (b) DNA.

Docking simulations with DNA indicated that no stable hydrogen bonds were formed between B3 and the DNA in the best-scoring poses, although weak interactions of this type were detected in some alternative configurations. This observation is consistent with the experimental data, which did not conclusively identify a dominant DNA binding mode. However, docking results suggest that intercalation is the preferred interaction mechanism. The lowest-energy intercalated pose of B3 within the DNA helix is shown in Figure 9b, where the compound clearly penetrates the intercalation cavity from the minor groove. This observation is consistent with the experimental data, which did not conclusively identify a dominant DNA binding mode. The lowest-energy intercalated pose of B3 within the DNA helix is shown in Figure 9b, where the compound clearly penetrates the intercalation cavity from the minor groove. Score difference between intercalation and groove binding (seen in Table 7) would suggest intercalation as the main binging mechanism but the method and scoring function that were used are parametrized for use with proteins and enzymes, not with DNA. Therefore, from these results, we conclude that both binding modes are possible based on low calculated scores and structural placement with no unfavorable clashes.

4. Conclusions

A series of novel cobalt(II) complexes with biologically relevant β-diketo ester ligands were synthesized and characterized. The yields were highly satisfactory, reaching up to 88%. All of the newly synthesized cobalt(II) complexes were characterized via UV-Vis, and FTIR spectroscopy, mass spectrometry (MS), and elemental analysis. Their biological activity was comprehensively evaluated through antimicrobial and antitumor assays. The antimicrobial activity of four selected cobalt(II) complexes was tested against a panel of five bacterial and five fungal strains. Among them, complex B1 exhibited the most potent antimicrobial properties, showing moderately strong antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Proteus mirabilis with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 0.23 mg/mL. Additionally, B1 demonstrated superior antifungal efficacy, particularly against Mucor mucedo, with an MIC of 0.01 mg/mL, significantly surpassing the standard antifungal agent, ketoconazole. Antitumor activity was assessed using the SW480 colorectal cancer cell line and the HaCaT normal human keratinocyte cell line. Complex B3 emerged as the most cytotoxic compound against SW480 cells, with an IC50 value of 11.49 µM, while complex B2 also showed notable cytotoxic effects. To gain insight into the mechanisms underlying the biological aWctivity, binding studies were conducted with calf thymus DNA (CT-DNA) and bovine serum albumin (BSA). Complex B3 exhibited a strong affinity for CT-DNA, predominantly through hydrophobic interactions, and demonstrated suitable binding characteristics with BSA. These experimental findings were further supported by molecular docking studies, which provided a clearer understanding of the binding modes and interactions at the molecular level. Taken together, the results of this study underscore the promising antimicrobial and antitumor potential of the synthesized cobalt(II) complexes. The observed biological activities, supported by mechanistic studies, highlight their potential as lead compounds for future development and suggest their strong promise for clinical application in the treatment of infectious diseases and cancer.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/analytica7010003/s1, Equations (S1)–(S7), Figure S1: UV-Vis spectra of cobalt(II) complex B1 (a), B2 (b), B3 (c), and B4 (d); Figure S2: FTIR spectra of cobalt(II) complex B1 (a), B2 (b), B3 (c), and B4 (d); Figure S3: Absorption spectra of cobalt complex at 288 K (top) and 298 K (bottom) in PBS buffer upon addition of CT-DNA. [complex] = 13.5 µM; [DNA] = 13.4–136 µM. The arrow presents the addition of increasing concentration of DNA. Insert: plot of [DNA]/(εa-εf) vs. [DNA]; Figure S4: The Van’t Hoff plot of ln Kb vs 1/T; Figure S5: Emission spectra of HOE-CT-DNA with cobalt complex [complex] = (5 µM–50 µM); Table S1: Centers of search space spheres and their radii for each experiment. All units are given in Angstrom (Å) as used in structural files.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.J. and J.P.; methodology I.F.; software N.J. and M.K.; validation N.J. and N.P.; formal analysis I.F., M.M. and S.S.; investigation, J.P.; resources D.N.; data curation I.F., M.M. and S.S.; writing—original draft, N.J.; writing—review & editing N.J., I.F., S.S., J.P., M.M., D.N., N.P. and M.K.; visualization I.F., D.N., M.M. and S.S.; project administration N.J.; funding acquisition M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Serbian Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development (Agreement No. 451-03-136/2025-03/200122 and 451-03-137/2025-03/200122).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hangan, A.C.; Oprean, L.S.; Dican, L.; Procopciuc, L.M.; Sevastre, B.; Lucaciu, R.L. Metal-based drug–DNA interactions and analytical determination methods. Molecules 2024, 29, 4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topală, T.L.; Fizeşan, I.; Petru, A.E.; Castiñeiras, A.; Bodoki, A.E.; Oprean, L.S.; Escolano, M.; Alzuet-Piña, G. Evaluation of DNA and BSA-Binding, Nuclease Activity, and Anticancer Properties of New Cu (II) and Ni (II) Complexes with Quinoline-Derived Sulfonamides. Inorganics 2024, 12, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, A.; Živanović, M.; Puchta, R.; Ćoćić, D.; Scheurer, A.; Milivojevic, N.; Bogojeski, J. Experimental and quantum chemical study on the DNA/protein binding and the biological activity of a rhodium (III) complex with 1,2,4-triazole as an inert ligand. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 9070–9085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karges, J.; Stokes, R.W.; Cohen, S.M. Metal complexes for therapeutic applications. Trends Chem. 2021, 3, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronconi, L.; Sadler, P.J. Using Coordination Chemistry to Design New Medicines. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2007, 251, 1633–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai-Yin Sun, R.; Ma, D.-L.; Wong, E.L.-M.; Che, C.-M. Some Uses of Transition Metal Complexes as Anti-Cancer and Anti-HIV Agents. Dalton Trans. 2007, 43, 4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, J.T.; Lipp, H.-P. Toxicity of Platinum Compounds. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2003, 4, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastry, J.; Kellie, S.J. Severe Neurotoxicity, Ototoxicity and Nephrotoxicity Following High-Dose Cisplatin and Amifostine. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2005, 22, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.P.; Tadagavadi, R.K.; Ramesh, G.; Reeves, W.B. Mechanisms of Cisplatin Nephrotoxicity. Toxins 2010, 2, 2490–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhinney, S.R.; Goldberg, R.M.; McLeod, H.L. Platinum Neurotoxicity Pharmacogenetics. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2009, 8, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loginova, N.V.; Harbatsevich, H.I.; Osipovich, N.P.; Ksendzova, G.A.; Koval’chuk, T.V.; Polozov, G.I. Metal complexes as promising agents for biomedical applications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 5213–5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, K.; Ghosh, D.; Kabi, B.; Chandra, A. A Concise Review on Cobalt Schiff Base Complexes as Anticancer Agents. Polyhedron 2022, 222, 115890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Lateef, H.M.; Ali, A.M.; Khalaf, M.M.; Abdou, A. New Iron(III), Cobalt(II), Nickel(II), Copper(II), Zinc(II) Mixed-Ligand Complexes: Synthesis, Structural, DFT, Molecular Docking and Antimicrobial Analysis. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiop. 2023, 38, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndagi, U.; Mhlongo, N.; Soliman, M. Metal Complexes in Cancer Therapy—An Update from Drug Design Perspective. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2017, 11, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joksimović, N.; Petronijević, J.; Ćoćić, D.; Ristić, M.; Mihajlović, K.; Janković, N.; Milović, E.; Klisurić, O.; Petrović, N.; Kosanić, M. Synthesis, Characterization, and Biological Evaluation of Novel Cobalt(II) Complexes with β-Diketonates: Crystal Structure Determination, BSA Binding Properties and Molecular Docking Study. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 29, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfrew, A.K.; O’Neill, E.S.; Hambley, T.W.; New, E.J. Harnessing the properties of cobalt coordination complexes for biological application. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 375, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joksimović, N.; Janković, N.; Davidović, G.; Bugarčić, Z. 2,4-Diketo Esters: Crucial Intermediates for Drug Discovery. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 105, 104343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sechi, M.; Bacchi, A.; Carcelli, M.; Compari, C.; Duce, E.; Fisicaro, E.; Rogolino, D.; Gates, P.; Derudas, M.; Al-Mawsawi, L.Q.; et al. From Ligand to Complexes: Inhibition of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Integrase by β-Diketo Acid Metal Complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 4248–4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joksimović, N.; Baskić, D.; Popović, S.; Zarić, M.; Kosanić, M.; Ranković, B.; Stanojković, T.; Novaković, S.B.; Davidović, G.; Bugarčić, Z.; et al. Synthesis, Characterization, Biological Activity, DNA and BSA Binding Study: Novel Copper(II) Complexes with 2-Hydroxy-4-Aryl-4-Oxo-2-Butenoate. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 15067–15077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joksimović, N.; Janković, N.; Petronijević, J.; Baskić, D.; Popovic, S.; Todorović, D.; Zarić, M.; Klisurić, O.; Vraneš, M.; Tot, A.; et al. Synthesis, Anticancer Evaluation and Synergistic Effects with CisPlatin of Novel Palladium Complexes: DNA, BSA Interactions and Molecular Docking Study. Med. Chem. 2020, 16, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joksimović, N.; Petronijević, J.; Janković, N.; Kosanić, M.; Milivojević, D.; Vraneš, M.; Tot, A.; Bugarčić, Z. Synthesis, Characterization, Antioxidant Activity of β-Diketonates, and Effects of Coordination to Copper(II) Ion on Their Activity: DNA, BSA Interactions and Molecular Docking Study. Med. Chem. 2021, 17, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimiza, F.; Fountoulaki, S.; Papadopoulos, A.N.; Kontogiorgis, C.A.; Tangoulis, V.; Raptopoulou, C.P.; Psycharis, V.; Terzis, A.; Kessissoglou, D.P.; Psomas, G. Non-Steroidal Antiinflammatory Drug–Copper(II) Complexes: Structure and Biological Perspectives. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 8555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proposed Standard M38-P; Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Conidium-Forming Filamentous Fungi. NCCLS (National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards): Wayne, PA, USA, 1998.

- Sarker, S.D.; Nahar, L.; Kumarasamy, Y. Microtitre Plate-Based Antibacterial Assay Incorporating Resazurin as an Indicator of Cell Growth, and Its Application in the in Vitro Antibacterial Screening of Phytochemicals. Methods 2007, 42, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milutinović, M.; Stanković, M.; Cvetković, D.; Maksimović, V.; Šmit, B.; Pavlović, R.; Marković, S. The Molecular Mechanisms of Apoptosis Induced by Allium Flavum L. and Synergistic Effects with New-Synthesized Pd(II) Complex on Colon Cancer Cells. J. Food Biochem. 2015, 39, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cellular Growth and Survival: Application to Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćoćić, D.; Jovanović-Stević, S.; Jelić, R.; Matić, S.; Popović, S.; Djurdjević, P.; Baskić, D.; Petrović, B. Homo- and Hetero-Dinuclear Pt(II)/Pd(II) Complexes: Studies of Hydrolysis, Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions, DNA/BSA Interactions, DFT Calculations, Molecular Docking and Cytotoxic Activity. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 14411–14431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radisavljević, S.; Ćoćić, D.; Petrović, B.; Kellner, I.; Ivanović-Burmazović, I.; Radenković, N.; Nikodijević, D.; Milutinović, M. New Dinuclear Gold(III) Complex with 1,5-Naphthyridine as Bridging Ligand: Synthesis, Characterization, DNA/BSA Binding Studies, and Anticancer Activity. Gold Bull. 2024, 57, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakowicz, J.R.; Weber, G. Quenching of Fluorescence by Oxygen. Probe for Structural Fluctuations in Macromolecules. Biochemistry 1973, 12, 4161–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-S.; Yuan, W.-B.; Wang, H.-Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, M.; Yu, K.-B. Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Interaction with DNA and HSA of (N,N′-Dibenzylethane-1,2-Diamine) Transition Metal Complexes. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2008, 102, 2026–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt-Ferreira, G.; de Azevedo, W.F., Jr. Molegro Virtual Docker for Docking. In Docking Screens for Drug Discovery; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, A.; Ajibade, P. An Insight into the Anticancer Activities of Ru(II)-Based Metallocompounds Using Docking Methods. Molecules 2013, 18, 10829–10856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozalp, L.; Sağ Erdem, S.; Yüce-Dursun, B.; Mutlu, Ö.; Özbil, M. Computational Insight into the Phthalocyanine-DNA Binding via Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2018, 77, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, H.R.; Wing, R.M.; Takano, T.; Broka, C.; Tanaka, S.; Itakura, K.; Dickerson, R.E. Structure of a B-DNA Dodecamer: Conformation and Dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 2179–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canals, A.; Purciolas, M.; Aymamí, J.; Coll, M. The Anticancer Agent Ellipticine Unwinds DNA by Intercalative Binding in an Orientation Parallel to Base Pairs. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2005, 61, 1009–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekula, B.; Zielinski, K.; Bujacz, A. Crystallographic Studies of the Complexes of Bovine and Equine Serum Albumin with 3,5-Diiodosalicylic Acid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 60, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, J.J.P. Optimization of Parameters for Semiempirical Methods VI: More Modifications to the NDDO Approximations and Re-Optimization of Parameters. J. Mol. Model 2012, 19, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision D.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Becke, A.D. Density-Functional Thermochemistry. III. The Role of Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, P.J.; Wadt, W.R. Ab Initio Effective Core Potentials for Molecular Calculations. Potentials for K to Au Including the Outermost Core Orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, R.; Christensen, M.H. MolDock: A New Technique for High-Accuracy Molecular Docking. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 3315–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medjedović, M.; Simović, A.R.; Ćoćić, D.; Milutinović, M.; Senft, L.; Blagojević, S.; Milivojević, N.; Petrović, B. Dinuclear Ruthenium(II) Polypyridyl Complexes: Mechanistic Study with Biomolecules, DNA/BSA Interactions and Cytotoxic Activity. Polyhedron 2020, 178, 114334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, K. Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabicky, J.; Rappoport, Z. The Chemistry of Metal Enolates; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pellei, M.; Del Gobbo, J.; Caviglia, M.; Gandin, V.; Marzano, C.; Karade, D.V.; Noonikara Poyil, A.; Dias, H.V.R.; Santini, C. Synthesis and Investigations of the Antitumor Effects of First-Row Transition Metal(II) Complexes Supported by Two Fluorinated and Non-Fluorinated β-Diketonates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munteanu, C.R.; Suntharalingam, K. Advances in Cobalt Complexes as Anticancer Agents. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 13796–13808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thamilarasan, V.; Sengottuvelan, N.; Sudha, A.; Srinivasan, P.; Chakkaravarthi, G. Cobalt(III) Complexes as Potential Anticancer Agents: Physicochemical, Structural, Cytotoxic Activity and DNA/Protein Interactions. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 162, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roszkowska, M. Multilevel mechanisms of cancer drug resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerapreeyakul, N.; Nonpunya, A.; Barusrux, S.; Thitimetharoch, T.; Sripanidkulchai, B. Evaluation of the Anticancer Potential of Six Herbs against a Hepatoma Cell Line. Chin. Med. 2012, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radisavljević, S.; Scheurer, A.; Bockfeld, D.; Ćoćić, D.; Puchta, R.; Senft, L.; Pešić, M.; Damljanović, I.; Petrović, B. New Mononuclear Gold(III) Complexes: Synthesis, Characterization, Kinetic, Mechanistic, DNA/BSA/HSA Binding, DFT and Molecular Docking Studies. Polyhedron 2021, 209, 115446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajlović, K.; Joksimović, N.; Radisavljević, S.; Petronijević, J.; Filipović, I.; Janković, N.; Milović, E.; Popović, S.; Matić, S.; Baskić, D. Examination of Antitumor Potential of Some Acylpyruvates, Interaction with DNA and Binding Properties with Transport Protein. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1270, 133943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambika, S.; Manojkumar, Y.; Senthilkumar, R.; Sathiyaraj, M.; Arunachalam, S. Nucleic Acid Binding and Invitro Cytotoxicity Studies of Polymer Grafted Intercalating Copper(II) Complex. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 2016, 26, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thederahn, T.; Spassky, A.; Kuwabara, M.D.; Sigman, D.S. Chemical Nuclease Activity of 5-Phenyl-1,10-Phenanthroline-Copper Ion Detects Intermediates in Transcription Initiation by E. Coli RNA Polymerase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990, 168, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarushi, A.; Lafazanis, K.; Kljun, J.; Turel, I.; Pantazaki, A.A.; Psomas, G.; Kessissoglou, D.P. First- and Second-Generation Quinolone Antibacterial Drugs Interacting with Zinc(II): Structure and Biological Perspectives. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2013, 121, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabadi, N.; Mahdavi, M. DNA Interaction Studies of a Cobalt(II) Mixed-Ligand Complex Containing Two Intercalating Ligands: 4,7-Dimethyl-1, 10-Phenanthroline and Dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine. Int. Sch. Res. Netw. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 2013, 604218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, C.; Rajput, C.; Thomas, J.A. Studies on the Interaction of Extended Terpyridyl and Triazine Metal Complexes with DNA. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006, 100, 1314–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeur, B.; Berberan-Santos, M.N. Molecular Fluorescence; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH and Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manojkumar, Y.; Ambika, S.; Arulkumar, R.; Gowdhami, B.; Balaji, P.; Vignesh, G.; Arunachalam, S.; Venuvanalingam, P.; Thirumurugan, R.; Akbarsha, M.A. Synthesis, DNA and BSA Binding, in Vitro Anti-Proliferative and in Vivo Anti-Angiogenic Properties of Some Cobalt(III) Schiff Base Complexes. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 11391–11407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.